|

|

U.S. Civil War Artillery, Cannon, Howitzers, and Mortars

A Photographic History of Light and Heavy Artillery

American Civil War Artillery and Cannon

Field, Siege and Garrison, and Seacoast (Coastal) Guns

Foreword

On the American Civil War battlefield (1861-1865), Napoleon's artillery

tactics were no longer practical. The infantry, armed with its own comparatively long-range firearm, was usually able to keep

artillery beyond case-shot range, and cannon had to stand off at such long distances that their primitive ammunition was relatively

ineffective. The result was that when attacking infantry advanced, the defending infantry and artillery were still fresh and

unshaken, ready to pour a devastating point-blank fire into the assaulting lines. Thus, in spite of an intensive 2-hour bombardment

by 138 Confederate guns at the crisis of Gettysburg, as the gray-clad troops advanced across the field to close range, double

canister and concentrated infantry volleys cut them down in masses.

Field artillery smoothbores, under conditions prevailing during the war,

generally gave better results than the smaller-caliber artillery rifle. A 3-inch rifle, for example, had twice the range

of a Napoleon; but in the broken, heavily wooded country where so much of the fighting occurred, the superior range of the

rifle could not be employed to full advantage. Neither was its relatively small and sometimes defective projectile as damaging

to personnel as case or grape from a larger caliber smoothbore. At the first battle of Manassas (July 1861) more than half

the 49 Federal cannon were rifled; but by 1863, even though many more rifles were in service, the majority of the pieces in

the field remained the old reliable 6- and 12-pounder smoothbores.

The range and accuracy of the rifles startled the world. A 30-pounder

(4.2-inch) Parrott had an astonishing distance of 8,453 yards (7729 meters), just shy of 5 miles (8 kilometers), with

80-pound hollow shot; the notorious "Swamp Angel" that fired on Charleston in 1863 was a 200-pounder Parrott mounted in the

marsh 7,000 yards from the city. But perplexing to both armies, neither rifles nor smoothbores could destroy earthworks.

As was proven several times during the war, the defenders of a well-built earthwork were able to repair the trifling damage

done by enemy fire almost as soon as there was a lull in the shooting. Learning this lesson, the determined Confederate

defenders of Fort Sumter in 1863-64 refused to surrender, but under the most difficult conditions converted their ruined masonry

into an earthwork almost impervious to further bombardment.

The following American Civil War work is a fascinating yet captivating read,

an encyclopedic photographic presentation and history of the conflict and its impressive artillery and cannon. This study

also shows that the artillerist was a well-trained and highly intelligent soldier, regardless of the color

of the uniform.

Introduction

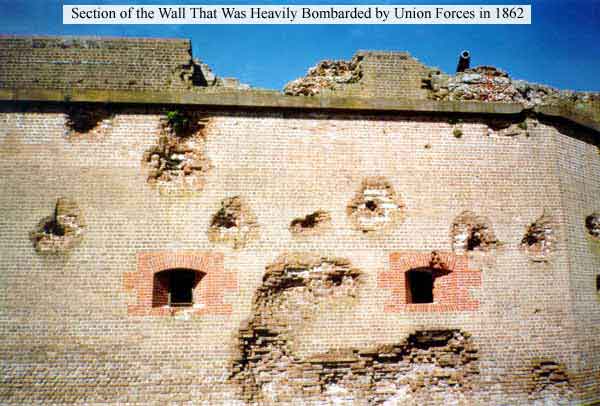

| Masonry fort damaged by rifled artillery |

|

| Fort Pulaski as a result of Union rifled artillery fire |

Artillery during the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) had many makes, models,

classifications, types, and characteristics, but each piece, whether referred to as a smoothbore garrison gun, rifled field

piece, or seacoast howitzer, was an integral part of both the Union and Confederate army organization known as the artillery

branch. The artillery branch was one of three principal branches that formed the army; the other two were the infantry and

cavalry. As the physical body has parts, and parts have functions, so did the Civil War army.

The infantry was the legs that carried the body into the brunt of the fighting, while the cavalry was the eyes that could

locate and direct the body prior, during and even after the battle (cavalry also fought, but mainly dismounted), and the artillery

was the arms that was capable of reaching out and touching the enemy from a distance. The body requires the legs, the arms,

and the eyes in order to function perfectly. Remove an eye, the body suffers. Remove a leg, the body suffers. Remove an arm

and a leg and the body suffers severely. So one member or part of the body is not more vital and significant

than another part, but together, each part forms the unit, the Civil War army unit. A well-disciplined and trained body, army

body, consisting of artillery, infantry, and cavalry functioning jointly, with each member performing its respective

responsibilities and roles, was the goal of both Northern and Southern armies. Most battles during the Civil War were lost

because the body was absent or missing a "part" prior or during the engagement. On the other hand, one army was victorious

during the battle because its body remained intact and functioned well.

(Right) Photograph of Union projectile damage to Fort Pulaski's walls. At 8:15 am on April 10, 1862, Union batteries opened fire on the eleven feet thick

walls of Fort Pulaski. Believed by most to be an impenetrable fortress, the smoothbore guns merely shook Pulaski's

walls “in a random manner,” but a battery of 30-pounder

Parrott Rifles thundered their projectiles with exceptional accuracy into the fort's walls and within 30 hours

the new rifled cannons had breached one of the fort's corner walls and shells now passed through the fort dangerously

close to the main powder magazine. With the loss of one soldier and absent the classic siege, the Confederate force

was compelled to surrender. The success of the siege was the use

of new rifled cannons by the Union artillery. These new weapons were able to fire their elongated projectiles farther and

more accurately than the smoothbore cannons that Fort Pulaski was built to withstand. The cannonading had transformed the newly

constructed masonry forts of the Third System of United States Coastal Defense from impenetrable bastions of ingenious

engineering to obsolete symbols of American paranoia and excess.

The American Civil War has been referred to as the last of the ancient wars and the first of

the modern wars. When the Civil War commenced, weaponry of all types was in short supply. Many soldiers were issued antiquated,

imported, and nearly obsolete weapons. However, by the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, a few quality types were obtained

in large numbers and became standard issue to the soldiers of both armies.

Although more innovative and experimental weaponry was introduced during the Civil War than all previous wars

combined, the military units relied on traditional Napoleonic-style tactics. Infantry fought in closely-knit formations of

two rows, each man standing side by side. This formation was devised when the smoothbore musket was the normal weapon on the

battlefield and the close ranks were a necessity due to the muskets limitations. With the advance of the rifle musket, which

included grooves in the barrel allowing much greater range and accuracy, officers, many who had been taught Napoleonic tactics

at West Point, continued to employ the outdated tactics during the conflict. An exception to the employment of the obsolete

tactics arrived late in the Civil War with trench warfare in the Eastern Theater. During the nearly ten month Richmond-Petersburg

Siege, trenches replaced the constant close range attack and counterassault, retreat and counterattack

tactics. Unfortunately, failure to adopt modern tactics with modern weapons, with few exceptions, resulted in unimaginable casualty

rates on the battlefield. While cannoneers were accustomed to being deployed at short distances and in close support

of infantry, the opposing infantrymen with rifled muskets could now decimate an entire artillery battery in minutes.

To assist in this artillery study, a glossary is located at the bottom of the page.

| Columbiad guns during the Civil War |

|

| Columbiad guns of the Confederate water battery at Warrington, FL. (Pensacola Bay), Feb. 1861 |

(Above) Formidable Columbiad guns of the Confederate water battery at Warrington,

Florida. Warrington was considered the "mouth and entrance to Pensacola Bay." February 1861. Photographed by W. O. Edwards

or J. D. Edwards of New Orleans, LA. Library of Congress. 77-HL-99-1.

Union Artillery

The Union Army entered the war with a strong advantage

in artillery. It had ample manufacturing capacity in Northern factories, and it had a well-trained and professional officer

corps manning that branch of the service. Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, who was the chief of artillery for the Army of the Potomac

for part of the war, was well recognized as a most efficient organizer of artillery forces, and he had few peers in the practice

of the sciences of gunnery and logistics. Another example was John Gibbon, the author of the influential Artillerist's Manual

published in 1863 (although Gibbon would achieve considerably more fame as an infantry general during the war). Shortly after

the outbreak of war, Brig. Gen. James Wolfe Ripley, Chief of Ordnance, ordered the conversion of old smoothbores into rifled

cannon and the manufacture of Parrott guns.

Parrott

"Class" Guns by Size

| Model |

Length |

Weight |

Munition |

Charge size |

Maximum range at elevation |

Flight time |

Crew size |

| 2.9-in (10-lb) Army Parrott |

73 in |

1,799 lb (816 kg) |

10 lb (4.5 kg) shell |

1 lb (0.45 kg) |

5,000 yd (4,600 m) at 20 degrees |

21 secs |

6 |

| 3.0-in (10-lb) Army Parrott |

74 in |

1,726 lb (783 kg) |

10 lb (4.5 kg) shell |

1 lb (0.45 kg) |

1,830 yd (1,670 m) at 5 degrees |

7 secs |

6 |

| 3.67-in (20-lb) Army Parrott |

79 in |

1,795 lb (814 kg) |

19 lb (8.6 kg) shell |

2 lb (0.91 kg) |

4,400 yd (4,000 m) at 15 degrees |

17 secs |

7 |

| 3.67-in (20-lb) Naval Parrott |

81 in |

1,795 lb (814 kg) |

19 lb (8.6 kg) shell |

2 lb (0.91 kg) |

4,400 yd (4,000 m) at 15 degrees |

17 secs |

7 |

| 4.2-in (30-lb) Army Parrott |

126 in |

4,200 lb (1,900 kg) |

29 lb (13 kg) shell |

3.25 lb (1.47 kg) |

6,700 yd (6,100 m) at 25 degrees |

27 secs |

9 |

| 4.2-in (30-lb) Naval Parrott |

102 in |

3,550 lb (1,610 kg) |

29 lb (13 kg) shell |

3.25 lb (1.47 kg) |

6,700 yd (6,100 m) at 25 degrees |

27 secs |

9 |

| 5.3-in (60-lb) Naval Parrott |

111 in |

5,430 lb (2,460 kg) |

50 lb (23 kg) or 60 lb (27 kg) shell |

6 lb (2.7 kg) |

7,400 yd (6,800 m) at 30 degrees |

30 secs |

14 |

| 5.3-in (60-lb) Naval Parrott (breechload) |

111 in |

5,242 lb (2,378 kg) |

50-lb or 60 lb (27 kg) shell |

6 lb (2.7 kg) |

7,400 yd (6,800 m) at 30 degrees |

30 secs |

14 |

| 6.4-in (100-lb) Naval Parrott |

138 in |

9,727 lb (4,412 kg) |

80 lb (36 kg) or 100 lb (45 kg) shell |

10 lb (4.5 kg) |

7,810 yd (7,140 m) at 30 degrees (80-lb) |

32 secs |

17 |

| 6.4-in (100-lb) Naval Parrott (breechload) |

138 in |

10,266 lb (4,657 kg) |

80 lb (36 kg) or 100 lb (45 kg) shell |

10 lb (4.5 kg) |

7,810 yd (7,140 m) at 30 degrees (80-lb) |

32 secs |

17 |

| 8-in (150-lb) Naval Parrott |

146 in |

16,500 lb (7,500 kg) |

150 lb (68 kg) shell |

16 lb (7.3 kg) |

8,000 yd (7,300 m) at 35 degrees |

180 |

? |

| 8-in (200-lb) Army Parrott |

146 in |

16,500 lb (7,500 kg) |

200 lb (91 kg) shell |

16 lb (7.3 kg) |

8,000 yd (7,300 m) at 35 degrees |

? |

? |

| 10-in (300-lb) Army Parrott |

156 in |

26,900 lb (12,200 kg) |

300 lb (140 kg) shell |

26 lb (12 kg) |

9,000 yd (8,200 m) at 30 degrees |

202.5 secs |

? |

(Above) While the 4.2-in (30-pounder) rifle was the most widely used

of the Parrott siege artillery, it had the honor of occasionally being employed as field artillery. The 30-pounder Parrott had

a total weight (Gun & Carriage) of 6,500 lbs. (3.25 tons) and it required 10 horses for transport.

The basic unit of Union artillery was the battery, which usually consisted of six guns. Attempts

were made to ensure that all six guns in a battery were of the same caliber, simplifying training and logistics. Each gun,

or "piece", was operated by a gun crew of eight, plus four additional men to handle the horses and equipment. Two guns operating under the control of a lieutenant were known as a "section". The battery of six guns was

commanded by a captain. Artillery brigades composed of five batteries were commanded by colonels and supported the infantry

organizations as follows: each infantry corps was supported directly by one artillery brigade and, in the case of the Army

of the Potomac, five brigades formed the Artillery Reserve. This arrangement, championed by Hunt, allowed artillery to be

massed in support of the entire army's objective, rather than being dispersed all across the battlefield. An example of the

tension between infantry commanders and artillery commanders was during the massive Confederate bombardment of Cemetery Ridge

on 3 July 1863, the third day of the Battle of Gettysburg. Hunt had difficulty persuading the infantry commanders, such as

Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, against using all of their artillery ammunition in response to the Confederate bombardment,

understanding the value to the defenders of saving the ammunition for the infantry assault to come, Pickett's Charge.

| Civil War artillery and cannon history |

|

| Civil War artillery battery |

At the start of the war, the U.S. Army had 2,283 guns in its arsenal, but

approximately 10% of these were field artillery pieces. By the end of the war, the army had amassed 3,325 guns,

of which 53% were field pieces. The army reported as "supplied to the army during the war" the following quantities: 7,892

guns, 6,335,295 artillery projectiles, 2,862,177 rounds of fixed artillery ammunition, 45,258 tons of lead metal, and 13,320

tons of gunpowder.

(Right) Union field artillery battery supporting infantry during Battle

of Fredericksburg. Practice, practice, practice, and more practice, were the words of many weary cannoneers prior to

firing a single shot in combat. But when the artillerists' indomitable efforts were finally demonstrated on

the battlefield, the results were evident to opposing sides. And it was practice that had meant the difference between life

and death. Napoleonic tactics made Civil War artillery

crucial to the outcome of many Civil War battles. Mass formations of soldiers, with great discipline, would march across open

fields and directly into enemy shot and shell from artillery pieces as viewed in the photo.

Confederate Artillery

The South was at a relative disadvantage to the North for deployment of

artillery. The industrial North had far greater capacity for manufacturing weapons, and the Union blockade of Southern ports

prevented many foreign arms from reaching the Southern armies. The Confederacy had to rely to a significant extent on captured

Union artillery pieces: either on the battlefield or by capturing armories, such as Harpers Ferry. The Confederate cannons

built in the South often suffered from the shortage of quality metals and shoddy workmanship. Another disadvantage was the

quality of ammunition. The fuzes needed for detonating shells and cases were frequently inaccurate, causing premature or delayed

explosions. All that, coupled with the Union gunners' initial competence and experience gained as the war progressed, led

Southern forces to dread assaults on Northern positions backed up by artillery. A Southern officer observed, "The combination

of Yankee artillery with Rebel infantry would make an army that could be beaten by no one."

Confederate batteries usually consisted of four guns, in contrast to the

Union's six. This was a matter of necessity, because guns were always in short supply. And, unlike the Union, batteries frequently

consisted of mixed caliber weapons. Confederate batteries were generally organized into battalions (versus the Union brigades)

of four batteries each, and the battalions were assigned to the direct support of infantry divisions. Each infantry corps

was assigned two battalions as an Artillery Reserve, but there was no such Reserve at the army level. The chief of artillery

for Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton, had considerable difficulty massing artillery

for best effect because of this organization.

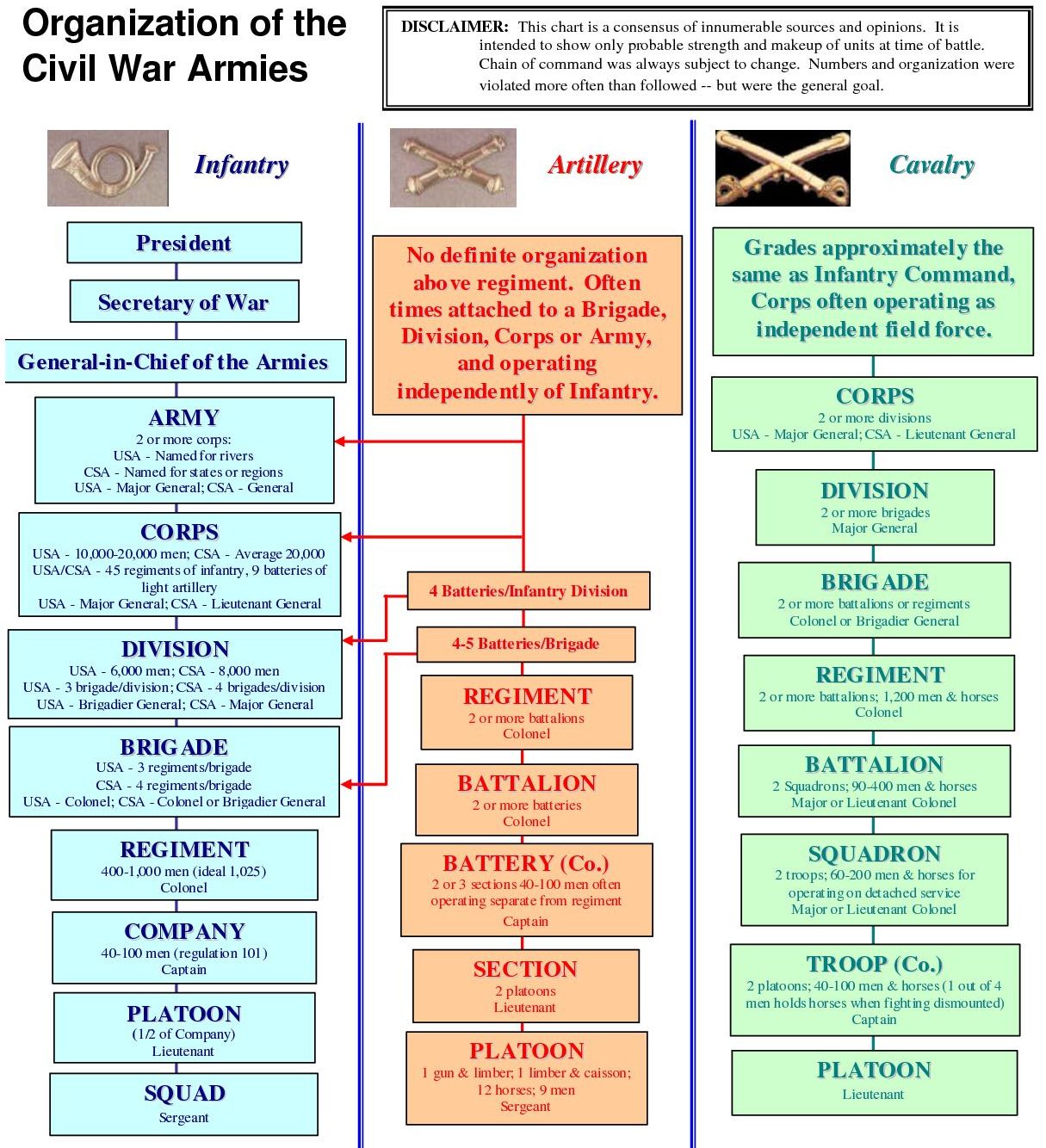

| Artillery was one of three Army components |

|

| The Civil War Army organization consisted primarily of infantry, .artillery, and cavalry |

| Civil War artillery battery formation |

|

| Civil War artillery battery in line, with acknowledgment of most widely used field pieces |

| Artillery trajectories |

|

| Civil War mortars, howitzers, and guns |

During the Civil War, the Artillery was a separate, specialized branch of

the army that supported the Infantry. The basic organizational unit for cannons was called a battery, comprised of four to

six guns with approximately 70-100 men commanded by a Captain. There were three types of artillery employed during the conflict:

field, siege and garrison, and seacoast. Although there were many models and sizes of guns, mortars, and howitzers, there

were two basic types--smoothbore and rifled.

Guns, when referring to artillery and cannon, were employed to batter heavy

construction with solid shot at long or short range; destroy fort parapets and, by ricochet fire, dismount cannon; shoot grape,

canister, or other projectiles against massed personnel. Mortars were used to destroy targets behind obstructions; use

high angle fire to shoot projectiles, destroying construction and killing personnel. During siege operations, mortars were

successful in lobbing explosive shells into trenches, and, with precision, could hit targets accustomed to the safety

of defilade. Howitzers, however, could be transported more easily in the field than mortars; destroy targets behind

obstructions by high angle fire; shoot larger projectiles than could field guns of similar weight.

The Union Army classified its artillery into three specific types,

depending on the gun's weight and intended use. Field artillery were light pieces that often traveled with the armies. Siege

artillery and garrison artillery were heavy artillery primarily used in military attacks on fortified places. Seacoast artillery were

the heaviest pieces and primarily designed to fire on attacking warships. The distinctions were subjective, because,

according to exigencies of war, field, siege and garrison, and seacoast artillery were all employed in various attacks

and defenses of fortifications. Although there were three specific types of artillery, the Union and Confederate military,

because of the gun's weight, usually grouped its artillery into two categories: light and heavy.

| Civil War artillery and cannon |

|

| Guns, Mortars, and Howitzers |

Field artillery was a category of light, mobile artillery used to support

armies in the field. Field pieces were specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, long range, short range and

extremely long range target engagement. Field artillery in the American Civil War refers to the important artillery weapons,

equipment, and practices used by the Artillery branch to support the infantry and cavalry forces in the field. Field artillery

was also known as foot artillery, for while the guns were pulled by beasts of burden (often horses), the gun crews would usually

march on foot, thus providing fire support mainly to the infantry. This was in contrast to horse artillery, aka flying artillery,

whose emphasis on speed while supporting cavalry units necessitated lighter guns and crews riding on horseback. Horse artillery

was a type of light, fast-moving and fast-firing artillery which provided highly mobile fire support to Civil War armies --

especially to cavalry units. It consisted of light cannons or howitzers attached to light but sturdy two-wheeled carriages

called caissons or limbers, with the crew riding horses or sometimes the caissons into battle. This was unlike field

artillery where the pieces were heavier and the crew marched on foot. "Stonewall" Jackson was cognizant of the advantages

of flying artillery, and he advocated that one should "strike the enemy first, then relocate your force rapidly, then strike

the enemy again, and continue the process until the enemy has been defeated..." Jackson had excelled in the application

of flying artillery during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), earning himself a promotion to brevet major, and he

would apply his textbook maneuvers during the Civil War. Preceding the Southern rebellion in 1861, Jackson taught artillery,

among other subjects, at Virginia Military Institute.

Siege and garrison artillery were heavy pieces that could be used either

in attacking or defending fortified places, but the weight and size of siege artillery prevented it from regularly traveling

with the armies. When needed, siege artillery and other material needed for siege operations were assembled into what was

called a siege train and transported to the army. In the Civil War, the siege train was always transported to the area of

the siege by water. The siege trains of the Civil War consisted almost exclusively of guns and mortars. Guns fired projectiles

on horizontal trajectory and could batter heavy construction with solid shot or shell at long or short range, destroy fort

parapets, and dismount cannon. Mortars fired shells in a high arcing trajectory to reach targets behind obstructions, destroying

construction and personnel.

Seacoast artillery, aka Coastal artillery, were the heaviest pieces

and were intended to be used in permanent fortifications along the seaboard. They were primarily designed to fire on attacking

warships. Seacoast artillery was employed according to exigencies of battle, however. For example, a Federal battery

with Model 1861 13-inch seacoast mortars was utilized during the Siege of Yorktown, Virginia, in 1862.

| Civil War Seacoast mortar on Morris Island, S.C. |

|

| Union Model 1841 10 in. Seacoast mortar during Siege of Charleston |

| Civil War Siege mortar |

|

| Confederate iron 24-pounder Coehorn mortar at Broadway Landing, Appomattox River, Virginia |

| Horse Artillery, aka Field Artillery |

|

| Horse Artillery. Battery M, 2nd U.S. Artillery in the field, 1862 |

Horses were required to pull the enormous weight of the cannon and ammunition;

on average, each horse pulled approximately 700 pounds (317.5 kg). Each gun in a battery used two six-horse teams: one team

pulled a limber that towed the gun, the other pulled a limber that towed a caisson. The large number of horses posed a logistical

challenge for the artillery, because they had to be fed, maintained, and replaced when worn out or injured. Artillery horses

were generally selected second from the pool of high quality animals; cavalry mounts were the best horses. The life expectancy

of an artillery horse was under eight months. They suffered from disease, exhaustion from long marches—typically 16

miles (25.8 km) in 10 hours—and battle injuries.

Because horses were large targets on the battlefield, when subjected

to counter-battery fire, their movements were made difficult because they were harnessed into teams. Robert Stiles wrote about

Union fire striking a Confederate battery on Benner's Hill at the Battle of Gettysburg:

"Such a scene as it presented—guns dismounted and disabled, carriages

splintered and crushed, ammunition chests exploded, limbers upset, wounded horses plunging and kicking, dashing out the brains

of men tangled in the harness; while cannoneers with pistols were crawling around through the wreck shooting the struggling

horses to save the lives of wounded men."

Acquiring horses proved challenging for the Union Army by 1864,

because it required 500 additional horses each day in order to sustain its presence in the field. Sheridan's army

alone, while contesting Early in the Shenandoah Valley in '64, consumed 150 steeds daily. The Confederate

military, on the other hand, could not replace man nor horse (nor munitions) in said year. The weight of attrition would

literally cause the fledgling nation to buckle and then collapse. See also Civil War Horses.

The term "horse artillery" refers

to the faster moving artillery batteries that typically supported cavalry regiments. The term "flying artillery" was

sometimes used as well. In such batteries, the artillerymen were all mounted, in contrast to batteries in which the artillerymen

walked alongside their guns. A prominent organization of such artillery in the Union Army was the U.S. Horse Artillery Brigade.

Horse artillery, or flying artillery, was an organization equipped usually

with 10-pounder rifled guns, with all hands mounted. In ordinary light artillery the cannoneers either rode on the gun-carriage

or walked. In flying artillery each cannoneer has a horse. This form was by far the most mobile of all, and was best suited

to accompany cavalry on account of its ability to travel rapidly. With the exception of the method of mounting the cannoneers,

there was not any difference between the classes of field batteries except as they were divided between “light”

and “heavy.”

Limber

The limber was a two-wheeled carriage that carried an ammunition

chest. It was connected directly behind the team of six horses and towed either a gun or a caisson. In either case, the combination

provided the equivalent of a four-wheeled vehicle, which distributed the load over two axles but was easier to maneuver on

rough terrain than a four-wheeled wagon. The combination of a Napoleon gun and a packed limber weighed 3,865 pounds (1,753.1

kg).

Caisson

The caisson was also a two-wheeled carriage. It carried two ammunition

chests and a spare wheel. A fully loaded limber and caisson combination weighed 3,811 pounds (1728.6 kg). The limbers, caissons,

and gun carriages were all constructed of oak. Each ammunition chest typically carried approximately 500 pounds (226.8 kg)

of ammunition or supplies. In addition to these vehicles, there were also battery supply wagons and portable forges that were

used to service the guns.

Cannon Crew

Eight

cannoneers were needed to fire field pieces. Five were at the gun--the gunner and cannoneers 1, 2, 3, 4. The gunner was in

charge of the piece, he gave the commands and conducted the aiming. Cannoneers 1-4 actually loaded, cleaned and fired

the gun. Cannoneer 5 carried the ammunition from the limber to the gun. Cannoneers 6 and 7 prepared ammunition and cut

the fuzes.

| Civil War cannon positions |

|

| Civil War cannoneers and their respective positions |

| How to load a cannon and fire a cannon |

|

| Loading and aiming a muzzle-loading smoothbore gun |

| Civil War artillery and cannon positions |

|

| Civil War artillery crew positions |

Weapons

Although the Union and Confederate artillery inventories consisted primarily

of muzzle-loaders, the two general types of muzzle-loading artillery weapons used during the Civil War were smoothbores and

rifles. Smoothbores included howitzers and guns. A smoothbore cannon barrel is just like a pipe, smooth on the inside. In

contrast, a rifled cannon has grooves cut into the inside of the barrel, which forced the ammunition to rotate like a football.

A rifled cannon was more accurate and had a greater range than a smoothbore gun. An example would be to throw a volleyball

and then a football at a target from a distance of 100 yards. While you would need a strong arm to achieve this task,

the volleyball would drift and deviate over the distance, while the rotating football would exhibit an effortless

flight with stunning accuracy.

Smoothbore versus Rifled

The two primary rifled guns employed by both sides were the 3-inch Ordnance

Rifle and the Parrott Rifle. The rifled cannon had three distinct advantages over the smoothbore. The first was the range

that these weapons could attain. The smoothbore Napoleon could negotiate 1,619 yards at a 5 degree elevation, while the

10-pounder Parrott and the 3-Inch Ordnance Rifle could achieve 2,000 yards and 1,835 yards respectively.

The second advantage was the rifling, which allowed the elongated projectile

to spiral and thus maintain a more accurate course to the target. The smoothbore Napoleons had spherical ammunition that navigated

a smooth barrel, exiting with far less accuracy. Thus, at greater ranges it was quite difficult to hit a target.

One celebrated exception was when the Confederate artilleryman "Pelham hit a Union standard-bearer at 800 yards with one shot".

While this might not appear challenging, the deviation of the ball in flight was 3 feet at 600 yards and 12 feet at 1,200

yards.

| British made Whitworth Breech-loader |

|

| 12 pdr. Whitworth Breechloading Rifle |

The third advantage to the rifled guns was that, shot for shot, they

used less gunpowder than the smoothbores. The reason for this was the windage of the smoothbores. This occurred because

a portion of the force from the exploding gunpowder would pass around the ball and not propel it. In the rifled guns, the

conical shot was more tightly fitted to the bore which considerably reduced the windage. When this was combined with the shape

itself of the conical shot, which retained velocity better than the round shot fired from the smoothbore, less powder was

required to propel the shot. This allowed a reduction in the weight of the gun as the amount of force on the breech was considerably

lessened. As a more direct comparison in gun weight, the 14-Pounder James Rifle fired a slightly heavier shot than the Napoleon,

but the gun weighed 300 pounds less and used 1.75 pounds less gunpowder.

Advantage of smoothbore field artillery, however, under conditions

prevailing during the Civil War, generally gave better results than the smaller-caliber rifle. A 3-inch rifle, for instance,

had twice the range of a Napoleon; but in the broken, heavily wooded country where much of the fighting took place, the superior

range of the rifle could not be used to full advantage. Neither was its relatively small and sometimes defective projectile

as damaging to personnel as case or grape from a larger caliber smoothbore.

Although rifled artillery eventually phased out the smoothbore, during the war both types

were appreciated as each employed its advantages on the battlefield.

Muzzle-loader vs. Breech-loader

Although muzzle-loading smoothbore cannon were used for almost 700 years,

the art of loading and aiming a muzzle-loading smoothbore and next generation rifled gun was simple in principle but

required exhaustive hours of training to acquire the necessary skill. While few breech-loading cannons were used during

the Civil War, they, however, proved problematic. But manufacturing and employment of breech-loaders during the

four year conflict was proceeded with decades of continued research and development of the weapon, thus resulting

in breech-loaders that quickly excelled and outclassed its counterpart, the muzzle-loader, in every characteristic.

While muzzle-loading was time consuming, breech-loading removed the

cumbersome muzzle-loader and it afforded: less exposure to men; reduced size of embrasures, securing greater rapidity

of fire; increased length of bore, and hence greater power; and also affording greater facilities for bore examinations, and

permitting an ease in loading not afforded in long-bored muzzle-loading guns; and the latter exhibiting the dangers arising

from the possibilities of double charging, and the cumbersomeness and complications of loading devices necessary for the use

of muzzle-loading guns, more especially in the naval service, where economy of space is a matter of vital importance. From

ship to shore, from nation to nation, the superiority of breech-loading guns is evident in the inventories of every army

and navy.

| Comparison of smoothbore and rifled cannon pieces |

|

| Comparison of the most widely employed Smoothbore cannon and rifled artillery pieces |

| Smoothbore and Rifled Cannon Types |

|

| Difference between smoothbore and rifled barrels |

(Above) Rifled artillery proved quickly that masonry fortifications were

obsolete. Smoothbore guns, however, demonstrated its continued lethality as an anti-personnel weapon.

Smoothbore Artillery

A smoothbore weapon is one which has a smooth barrel, and is absent rifling.

Smoothbores ranged from small arms to heavy siege and garrison guns. Early firearms had smooth barrels, and fired projectiles

with no significant spin. These projectiles had to have stable shapes, such as finned arrows or spheres, to minimize tumbling

during flight. However, spherical bullets do tend to rotate randomly during flight, and the Magnus effect means that even

a relatively smooth sphere will curve when rotating on any axis not parallel to the direction of travel.

Smoothbore artillery refers to weapons that were not rifled. At the time of the Civil War, metallurgy

and other supporting technologies had just recently evolved to a point allowing the large scale production of rifled field

artillery. As such, many smoothbore weapons were still in use and production even at the end of the war. Smoothbore field

artillery of the day fit into two role-based categories: guns and howitzers. Further classifications of the weapons were made

based on the type of metal used, typically bronze or iron (cast or wrought), although some examples of steel were produced.

Additionally, the artillery was often identified by the year of design in the Ordnance department references.

| Smoothbore barrel |

|

| Inside smoothbore barrel |

The smoothbore artillery was also categorized by the bore dimensions, based on the rough weight

of the solid shot projectile fired from the weapon. For instance a 12-pounder field gun fired a 12 pound solid shot projectile

from its 4.62-inch (117 mm) diameter bore. It was practice, dating back to the 18th century, to mix gun and howitzers into

batteries. Pre-war allocations called for 6-pounder field guns matched with 12-pounder howitzers, 9 and 12-pounder field guns

matched with 24-pounder howitzers. But the rapid expansions of both combatant armies, mass introduction of rifled artillery,

and the versatility of the 12-pounder "Napoleon" class of weapons all contributed to a change in the mixed battery practices.

Smoothbore guns were designed to fire solid shot projectiles at high velocity, over low

trajectories at targets in the open, although shot and canister were acceptable for use. The barrels of the guns were longer

than corresponding howitzers, and called for higher powder charges to achieve the desired performance. Field guns were produced

in 6-pounder (3.67 inch bore), 9-pounder (4.2 inch bore), and 12-pounder (4.62 inch bore) versions. Although some older iron

weapons were pressed into service, and the Confederacy produced some new iron field guns, most of those used on the battlefields

were of bronze construction. The 6-pounder field gun was well represented by bronze Models of 1835,

1838, 1839, and 1841 early in the war. Even a few older iron Model of 1819 weapons were pressed into service. Several hundred

were used by the armies of both sides in 1861. But in practice the limited payload of

the projectile was seen as a shortcoming of this weapon. From mid-war on, few 6-pounders saw action in the main field armies.

The larger 9- and 12-pounders were less well represented.

While the 9-pounder was still listed on Ordnance and Artillery manuals in 1861, very few were ever produced after the War

of 1812 and only scant references exist to Civil War use of the weapons. The 12-pounder field gun appeared in a series

of models mirroring the 6-pounder, but in far less numbers. At least one Federal battery, the 13th Indiana, took the 12-pounder

field gun into service early in the war. The major shortcoming of these heavy field guns was mobility, as they required eight-horse

teams as opposed to the six-horse teams of the lighter guns. A small quantity of 12-pounder field guns were rifled early in

the war, but these were more experimental weapons, and no field service is recorded.

| Civil War artillery battery |

|

| Union artillery battery in line |

The most popular smoothbore cannon for both the Union and Confederate

artillery was the 12-pounder Model 1857, Light, commonly called "Napoleon". The Model 1857 was of lighter weight than the

previous 12-pounder guns, and could be pulled by a six-horse draft, yet offered the heavier projectile payload of the larger

bore. It is sometimes called, confusingly, a "gun-howitzer" (because it possessed characteristics of both gun and howitzer).

The twelve-pounder "Napoleon" smoothbore cannon was named after Napoleon

III of France and was widely admired because of its safety, reliability, and killing power, especially at close range. In

Union Ordnance manuals it was referred to as the "light 12-pounder gun" to distinguish it from the heavier and longer 12 pounder

gun (which was virtually unused in field service.) It did not reach America until 1857. It was the last cast bronze gun used

by an American army. The Federal version of the Napoleon can be recognized by the flared front end of the barrel, called the

muzzle-swell. It was, however, relatively heavy compared to other artillery pieces and difficult to move across rough terrain.

Confederate Napoleons were produced in at least six variations, most of

which had straight muzzles, but at least eight catalogued survivors of 133 identified have muzzle swells. Additionally, four

iron Confederate Napoleons produced by Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond have been identified, of an estimated 125 cast. In

early 1863, Robert E. Lee sent the majority of the Army of Northern Virginia's bronze 6-pounder guns to Tredegar to be melted

down and recast as Napoleons. Copper for casting bronze pieces became increasingly scarce to the Confederacy throughout the

war and became acute in November 1863 when the Ducktown copper mines near Chattanooga were lost to Union forces. Casting of

bronze Napoleons by the Confederacy ceased and in January 1864 Tredegar began producing iron Napoleons.

Commonly referred to as the "Napoleon", the M1857 12-pdr. Napoleon bronze

smoothbore cannon fired a twelve-pound ball and was considered a light gun through each weighed an average of 1,200 pounds.

This powerful cannon could fire explosive shells and solid shot up to a mile and charges of canister to 300 yards with

accuracy. The Napoleon was a favorite amongst some Northern artillerists because of its firepower and reliability. Two Union

batteries armed with Napoleons at Gettysburg were very effective in holding back Confederate infantry attacks and knocking

down opposing Southern batteries. Battery G, 4th U.S. repeatedly slowed Confederate infantry attacks against the Eleventh

Corps lines on July 1, while Captain Hubert Dilger's Battery G, 1st Ohio Light Artillery almost annihilated two Confederate

batteries with accurate and punishing counter-battery fire at long distance. Most Union Napoleons were manufactured in Massachusetts

by the Ames Company and the Revere Copper Company. Confederate industry replicated the Napoleon design at several foundries

in Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina. The Confederate design differed slightly from

Union-made guns but fired the same twelve pound shot, shell and canister rounds used in Union manufactured guns.

| Horses died in great numbers on the battlefield |

|

| Dead horses on the Civil War battlefield |

The howitzer was a short-barreled smoothbore artillery piece designed to

fire large projectiles at high trajectories.

Howitzers were short-barreled guns that were optimized for firing

explosive shells in a high trajectory at nearby concealed targets, but also for spherical case shot and canister, over a shorter

range than the guns. Howitzers were considered the weapon of choice when the

opposing forces were concealed behind terrain features or fortifications. Howitzers used lower powder charges than guns of

corresponding caliber. Field howitzer calibers used in the Civil War were 12-pounder (4.62 inch bore), 24-pounder (5.82 inch

bore), and 32-pounder (6.41 inch bore). Most of the howitzers used in the war were bronze, with notable exceptions of some

of Confederate manufacture.

(Right) Horses, as large animals, made large targets. Intentionally

or accidentally, the horse was often caught between the warring sides and the result was catastrophic. Because cavalry

and artillery relied heavily on the procurement of strong, fit horses the demand quickly outstripped the meager supply. Both

armies, however, resorted to employing mules and others pack animals as substitutes. Several thousand horses were

killed during battle, but thousands also succumbed to the excessive demands of Civil War. In the midst of a single

major battle, it was the norm to view hundreds of dead horses scattered across the battlefield. It was also commonplace

to observe several horses simply collapse to the ground and die from exhaustion.

During battle, when horses fell dead constantly, soldiers sought shelter behind the dead animals. See also Civil War Horses.

Coupled

to the 6-pounder smoothbore field gun in allocations of the pre-war Army, the 12-pounder field howitzer was

represented by Models of 1838 and 1841. With a light weight and respectable projectile payload, the 12-pounder was only cycled

out of the Union field army inventories as production and availability of the 12-pounder "Napoleon" replaced it, but the howitzer

remained in Confederate service for the duration of the conflict.

As with the corresponding heavy field guns, the heavier Howitzers were available

in limited quantities early in the war. Both Federal and Confederate contracts list examples of 24-pounders delivered during

the war, and surviving examples exist of imported Austrian types of this caliber used by the Confederates. These 24-pounder

Howitzers found use in the "reserve" batteries of the respective armies, but were gradually replaced over time with heavy

rifled guns. Both the 24- and 32-pounders were more widely used in fixed fortifications.

Principal characteristics of common smoothbore Field Artillery

| M1857 Napoleon Smoothbore Cannon |

|

| Model 1857 12-pounder Napoleon Light |

| Smoothbore Artillery |

|

Field Artillery

Piece |

Bore

diameter

(inches) |

Material |

Length

of tube

(inches) |

Weight

of tube

(pounds) |

Weight of

projectile

(pounds) |

Weight of

charge

(pounds) |

Muzzle

velocity

(ft./sec.) |

Range at 5°

elevation

(yards) |

M1841 6-pdr. Gun

. |

3.67 |

Bronze |

60.0 |

884 |

6.10 |

1.25 |

1,439 |

1,523 |

M1841 12-pdr. Gun

. |

4.62 |

Bronze |

78.0 |

1,757 |

12.30 |

2.50 |

1,486 |

1,663 |

M1841 12-pdr.

Howitzer |

4.62 |

Bronze |

53.0 |

788 |

*8.90 |

1.00 |

1,054 |

1,072 |

M1841 24-pdr.

Howitzer

|

5.82 |

Bronze |

64.0 |

1,318 |

*18.40 |

2.00 |

1,060 |

1,322 |

M1841 32-pdr.

Howitzer |

6.40 |

Bronze |

75.0 |

1,920 |

*25.60 |

2.50 |

1,100 |

1,504 |

M1841 12-pdr.

Mountain Howitzer |

4.62 |

Bronze |

32.9 |

220 |

*8.90 |

0.50 |

650 |

900 |

M1857 12-pdr. Napoleon

. |

4.62 |

Bronze |

66.0 |

1,227 |

12.30 |

2.50 |

1,440 |

1,619 |

* Weight of shell.

Rifled Artillery

The cannon made the transition from smoothbore

firing cannonballs to rifled firing shells in the 19th century. Rifling is the process of making helical grooves in the barrel

of a gun or firearm, which imparts a spin to a projectile around its long axis. This spin serves to gyroscopically stabilize

the projectile, improving its aerodynamic stability and accuracy. The Civil War was the first major war to see the use of

rifled artillery. Rifling gave the guns greater velocity, range, accuracy and penetrating power, making smoothbore siege guns

obsolete. Rifled guns were very effective against stone, brick, and masonry fortifications, but considered ineffective against

earthen field works and in trench warfare. A rifled barrel, having spiral grooves or polygonal rifling, imparts a gyroscopic

spin to the projectile that stabilizes it in flight and prevents it from tumbling. This does two things; first, it increases

the accuracy of the projectile by eliminating the random drift due to the Magnus effect, and second, it allows a longer, heavier

bullet to be fired from the same caliber barrel, increasing range and power. In the eighteenth century, the standard infantry

arm was the smoothbore musket; by the nineteenth century, rifled barrels became the

norm, increasing the power and range of the infantry weapon significantly.

| looking into the barrel |

|

| rifling grooves |

The 3-inch (76 mm) rifle, aka 3-Inch Ordnance rifle, was

the most widely used rifled gun during the war. Invented by John Griffen, it was extremely durable, with the barrel made of

wrought iron, primarily produced by the Phoenix Iron Company of Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. There are few cases on

record of the tube fracturing or bursting, a problem that plagued other rifles made of brittle cast iron. Initially, some

skeptical politicians and officers thought, would damage can this 3-inch rifle inflict? The rifle, however, had exceptional

accuracy. During the Battle of Atlanta, a Confederate gunner was quoted: "The Yankee three-inch rifle was a dead shot at any

distance under a mile. They could hit the end of a flour barrel more often than miss, unless the gunner got rattled."

This sleek weapon was also called the 3-inch Ordnance Rifle and was designed

by John Griffen, superintendent of the Safe Harbor Iron Works in Pennsylvania. This iron gun was similar in length of

the Parrott Rifle, fired an elongated shell, and was deadly accurate up to a mile. Much lighter than the Napoleon, the gun

weighed an average of 800 pounds and could be easily transported and manhandled by its crew. Only a limited number of

the Ordnance rifles were produced at Confederate arsenals.

Principal characteristics of common rifled Field Artillery

| Civil War Artillery and the Parrott Rifle |

|

| 20-pounder Parrotts, 1st Conn. Artillery, Ft. Richardson, Arlington Heights, VA. |

| Rifled Artillery |

|

Field Artillery

Piece |

Bore

diameter

(inches) |

Material |

Length

of tube

(inches) |

Weight

of tube

(pounds) |

Weight of

projectile

(pounds) |

Weight of

charge

(pounds) |

Muzzle

velocity

(ft./sec.) |

Range at 5°

elevation

(yards) |

M1861 10-pdr.

Parrott Rifle |

*2.90 |

Cast

Iron |

74.0 |

890 |

9.50 |

1.00 |

1,230 |

1,850 |

M1862 20-pdr.

Parrott Rifle

|

3.67 |

Cast

Iron |

84.0 |

1,750 |

20.00 |

2.00 |

1,250 |

1,900 |

M1861 3-inch

Ordnance Rifle

|

3.00 |

Wrought

Iron |

69.0 |

820 |

9.50 |

1.00 |

1,230 |

1,830 |

M1861 14-pdr.

James Rifle

|

3.67 |

Bronze |

60.0 |

875 |

12.00 |

.75 |

1,000 |

1,700 |

M1861 24-pdr.

James Rifle |

4.62 |

Bronze |

78.0 |

1,750 |

24.00 |

1.50 |

1,000 |

1,800 |

M1861 12-pdr.

Blakely Rifle

|

3.40 |

Steel |

59.0 |

800 |

10.00 |

1.00 |

1,250 |

1,850 |

6-pdr. Whitworth

Breechloading Rifle |

2.15 |

Steel |

70.0 |

700 |

6.00 |

1.00 |

1,550 |

2,750 |

12-pdr. Whitworth

Breechloading Rifle |

2.75 |

Steel |

104.0 |

1,092 |

12.00 |

1.75 |

1,500 |

2,800 |

12-pdr. Whitworth

Muzzleloading Rifle |

2.75 |

Steel |

84.0 |

1,000 |

12.00 |

2.00 |

1,600 |

3,000 |

6-pdr. Wiard Rifle

.

|

2.56 |

Steel |

56.0 |

600 |

6.00 |

0.60 |

1,300 |

1,800 |

10-pdr. Wiard Rifle

. |

3.00 |

Steel |

58.0 |

790 |

10.00 |

1.00 |

1,230 |

1,850 |

3-inch Armstrong

Muzzleloading Rifle |

3.00 |

Steel |

76.0 |

996 |

12.00 |

1.25 |

1,350 |

2,200 |

3-inch Armstrong

Breechloading Rifle |

3.00 |

Steel |

83.0 |

918 |

12.00 |

1.25 |

1,300 |

2,100 |

* The M1861 Parrott had a 2.90 inch bore diameter, while the M1863

Parrott had a 3.00 inch bore diameter.

Projectiles

Four basic types of projectiles were employed by Civil War field artillery:

solid shot, shells, case shot, and canister. Ammunition came in wide varieties, designed to attack specific targets.

A typical Union artillery battery (armed with six 12-pounder Napoleons) carried the following ammunition going into battle:

288 shot, 96 shells, 288 spherical cases, and 96 canisters.

| Civil War Artillery and Cannon Ammunition |

|

| Types of Artillery Projectiles |

(Right)

A) Solid shot attached to wooden sabot with straps.

B) Shell-complete

fixed round. Cartridge bag tied to sabot. Paper bag in place.

C) Arrangement of straps for shot (1) and shell (2) (opening

allowed for fuze).

D) Cartridge block for separate cartridge. Projectile and powder charge for rounds for guns larger

than 12-pounders were usually loaded separately.

E) Shell and sabot.

F) Spherical case: 12-pounder. contained 4.5-ounce

burster and 78 musket balls.

G) Canister: 12-pounder contained 27 cast-iron shots, average weight is 0.43 pounds in tin

case, nailed to sabot.

H) Complete fixed round of canister. Paper bag was torn off before loading.

I) Tapered sabot

for howitzers (powder chamber in howitzers was smaller than the bore).

Shot was a solid projectile that included no explosive charge. For a smoothbore,

the projectile was a round "cannonball". For a rifled gun, the projectile was referred to as a bolt and had a cylindrical

or spherical shape. In both cases, the projectile was used to impart kinetic energy for a battering effect, particularly effective

for the destruction of enemy guns, limbers and caissons, and wagons. It was also effective for mowing down columns of infantry

and cavalry and had psychological effects against its targets. Despite its effectiveness, many artillerymen were reluctant

to use solid shot, preferring the explosive types of ordnance. With solid projectiles, accuracy was the paramount consideration,

and they also caused more tube wear than their explosive counterparts. While

rifled cannon had much greater accuracy on average than smoothbores, the smoothbores had an advantage firing round shot relative

to the bolts fired from rifled pieces. Round shot could be employed in ricochet or rolling fire extending the depth and range

of its effect on land or water while bolts tended to dig in rather than ricochet.

|

| Case, aka Shrapnel |

Shell

Shells included an explosive charge and were designed to burst into fragments

in the midst of enemy infantry or artillery. For smoothbores, the projectile was referred to as "spherical shell". Shells

were more effective against troops behind obstacles or earthworks, and they were good for destroying wooden buildings by setting

them on fire. They were ineffective against good quality masonry. A primary weakness of shell was that it typically produced

only a few large fragments, the count increasing with caliber of the shell. A Confederate mid-war innovation perhaps influenced

by British ordnance/munition imports was the "polygonal cavity" or "segmented" shell which used a polyhedral cavity core to

create lines of weakness in the shell wall that would yield more regular fragmentation patterns—typically 12 similarly

sized fragments. While segmented designs were most common in spherical shell, it was applied to specific rifled projectiles

as well. Spherical shell used time fuzes, while rifled shell could use

timed fuze or be detonated on impact by percussion fuze. Fuze reliability was a concern; any shell that buried itself into

the earth before detonating had little anti-personnel effectiveness. However, large caliber shells, such as the 32-pounder

spherical were effective at breaching entrenchments.

Case (or shrapnel)

Case (or "spherical case" for smoothbores) were anti-personnel projectiles

carrying a smaller burst charge than shell, but designed to be more effective against exposed troops. While shell produced

only a few large fragments, case was loaded with lead or iron balls and was designed to burst above and before the enemy line,

showering down many more small but destructive projectiles on the enemy. The effect was analogous to a weaker version of canister.

With case the lethality of the balls and fragments came from the velocity of the bursting projectile itself—the small

burst charge only fragmented the case and dispersed the shrapnel. The spherical case used in a 12-pounder Napoleon contained

78 balls. The name shrapnel derives from its inventor, Henry Shrapnel. The

primary limitations to case effectiveness came in judging the range, setting the fuze accordingly, and the reliability and

variability of the fuze itself.

Canister (or case-shot)

Canister shot was the deadliest type of ammunition, consisting of a thin

metal container loaded with layers of lead or iron balls packed in sawdust. Upon exiting the muzzle, the container disintegrated,

and the balls fanned out as the equivalent of a shotgun blast. The effective range of canister was only 400 yards (370 m),

but within that range dozens of enemy infantrymen could be mowed down. Even more devastating was "double canister", generally

used only in dire circumstances at extremely close range, where two containers of balls were fired simultaneously. Canister shot, also known as case shot, was a kind of anti-personnel ammunition used

in cannons. Canister shot was packaged in a tin or brass container, possibly

guided by a wooden sabot. Canister balls did not have to punch through the wooden hull of a ship, so were smaller and more

numerous. The later shrapnel shell was similar, but with a much greater range. Canister also played a key role in dispersing

the troops assigned to support Pickett's Charge during the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863.

| Cannon headshot from canister shot |

|

| Canister ball headshot, 12-pounder field howitzer |

(Right) Result of a headshot

caused by a single iron canister ball fired from the 12-pounder field howitzer. This skull was discovered in 1876 on Morris

Island, South Carolina, near the site of Battery Wagner, a powerful earthwork fort that had protected the entrance to Charleston

Harbor during the Civil War. The skull belonged to a man of African descent—a soldier of the famous 54th Massachusetts

Volunteers, which had led the assault on Wagner on the night of July 18, 1863. Of approximately 600 men who made the charge,

256 were killed, wounded, or missing. From the size of the wound, and the remains of the projectile itself, it can be determined

what type of munition hit this man: an iron canister ball from one of two 12-pounder field howitzers known to have been used

in the repulse of that attack. The 54th Massachusetts Volunteers was not the first black regiment in the Civil War, nor was

it the first to fight. However, it was the first black regiment raised entirely of free men enrolled on exactly the same footing

as white troops and the first to engage in a major action well-covered by the national press. Its gallant conduct in the doomed assault on Battery Wagner, at Charleston, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863, electrified

the nation and proved once and for all that the black man, given the opportunity, could learn the soldier’s trade, and

fight as well as any white man.

Grapeshot

Grapeshot was a type of shot that is not one solid element, but a mass of small metal balls or

slugs packed tightly into a canvas bag. It was used both in land and naval warfare. When assembled, the balls resembled a

cluster of grapes, hence the name. On firing, the balls spread out from the muzzle, giving an effect similar to a giant shotgun.

Grapeshot was devastatingly effective against massed infantry at short range. It was used to savage massed infantry charges

quickly. Cannons would fire solid shot to attack enemy artillery and troops at longer range and switch to grape when they

or nearby troops were charged. Grapeshot was the predecessor of, and a variation on, canister,

in which a smaller number of larger metal balls were arranged on stacked iron plates with a threaded bolt running down the

center to hold them as a unit inside the barrel. It was used at a time when some cannons burst when loaded with too much gunpowder,

but as cannons got stronger, grapeshot was replaced by canister. A grapeshot round (or "stand") used in a 12-pounder Napoleon

contained 9 balls, contrasted against the 27 smaller balls in a canister round. By the time of the Civil War, grapeshot was

obsolete and largely replaced by canister. The period Ordnance and Gunnery work states that grape was excluded from "field

and mountain services." Few, if any, rounds were issued to field artillery batteries. Scattershot was an improvised form of

grapeshot which uses chain links, nails, shards of glass, rocks or other similar objects as the projectiles. Although scattershot

can be cheaply made, it was less effective than grapeshot due to the lack of uniformity in the projectiles' mass, shape, material,

and resultant ballistics.

Field Artillery

Field artillery was a category of light, mobile artillery used to support armies in the field. Field

pieces were specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, and both short and long range engagements. Field artillery

generally supported infantry and cavalry on the battlefield.

Although Parrott rifled-guns (Parrott Class) and Napoleon smoothbores were coveted

by both Union and Confederate forces, the Model 1861 3-inch Wrought Iron rifle, aka Ordnance Rifle, was the most common rifled

field piece on the battlefield, while the Model 1857 Napoleon, Light, was the most widely used artillery

piece during the Civil War.

Robert Parker Parrott (1804–77), an 1824 graduate of the United States Military Academy,

developed a new form of rifled artillery using a cast iron barrel with a reinforcing wrought iron band around the breech.

He initially produced 2.9-inch (10-pounder) and 3.67-inch (20-pounder) rifles for the field artillery. He later produced

four larger rifled guns that were used as siege artillery. These heavy Parrott rifles became the mainstays of the Federal

siege train. In early 1863, Robert E. Lee sent nearly all of the Army of Northern Virginia's obsolete (Mexican-American War

era) bronze 6-pounder guns to Tredegar to be melted down and recast as Napoleons.

The principal guns widely employed in the field and their respective characteristics

| Most widely used field artillery of the Civil War |

|

| U.S. Model 1857 12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore cannon |

| Field

Artillery Weapons and Characteristics |

|

Field Artillery

Piece |

Bore

diameter

(inches) |

Material |

Length

of tube

(inches) |

Weight

of tube

(pounds) |

Weight of

projectile

(pounds) |

Weight of

charge

(pounds) |

Muzzle

velocity

(ft./sec.) |

Range at 5°

elevation

(yards) |

| 6-pounder Gun |

3.67 |

Bronze |

60.0 |

884 |

6.10 |

1.25 |

1,439 |

1,523 |

| M1857 12-pounder "Napoleon" |

4.62 |

Bronze |

66.0 |

1,227 |

12.30 |

2.50 |

1,440 |

1,619 |

| 12-pounder Howitzer |

4.62 |

Bronze |

53.0 |

788 |

8.90 |

1.00 |

1,054 |

1,072 |

| 12-pounder Mountain Howitzer |

4.62 |

Bronze |

33.0 |

220 |

8.90 |

.50 |

------ |

1,005 |

| 24-pounder Howitzer |

5.82 |

Bronze |

64 .0 |

1,318 |

18.40 |

2.00 |

1,060 |

1,322 |

| 10-pounder Parrott Rifle

|

2.9 & 3.0 |

Iron |

74.0 |

890 |

9.50 |

1.00 |

1,230 |

1,850 |

| 3-inch Ordnance Rifle |

3.00 |

Wrought Iron |

69.0 |

820 |

9.50 |

1.00 |

1,215 |

1,830 |

| *14-pounder James Rifle |

3.80 |

Bronze |

60.0 |

875 |

14.00 |

1.25 |

------ |

1,530 |

| 20-pounder Parrott Rifle |

3.67 |

Iron |

84.0 |

1,750 |

20.00 |

2.00 |

1,250 |

1,900 |

12-pounder Whitworth Breechloading

Rifle

. |

2.75 |

Iron/Steel |

104.0 |

1,092 |

12.00 |

1.75 |

1,500 |

2,800 |

Italics denotes data for shell, not shot.

* Hazlett, pp. 151-152. This is for Hotchkiss shell

of 14lb @ 5 degrees. Hazlett used the only primary source: Abbot's Siege Artillery, p. 116. Hazlett also determined bore and

Type I based on text description and shell weight--matching recorded weights of modern recoveries (see Dickey pp. 137-139,143-146.)

Coles' data table and many others based on Peterson's 1959 book have impossibly small powder charge for range and weight given.

Later 14-pounder James types with Ordnance profile had longer barrels with 7.5" greater bore length (13% increase) and therefore

would have increased range.

The M1857 12-pounder Napoleon was a bronze smoothbore with an effective

range of 1,000 yards and a range of 1,619 yards at five degrees elevation. It fired solid shot, shell, case shot and canister

rounds with a 2 1/2 lb. charge of powder. The gun with its carriage and equipment weighed 2,500 lbs. and was served by a crew

of eight. (Casualties of disease and battle often reduced the crew to the minimum of three men.) While the Model 1857 12-pounder,

Light, commonly known as "Napoleon," was the most widely used "smoothbore field cannon" during the Civil War, the most

widely employed "rifled field piece" was the 3-inch Ordnance rifle, commonly known as 3-inch Wrought Iron rifle. Both

the M1857 Napoleon and 3-in. Ordnance rifle were coveted by both armies.

|

|

|

|

|

(Left) Union officers with a 3-inch Ordnance rifle. The 3-inch Ordnance

rifle, aka 3-inch Wrought iron rifle, was the most employed rifled field piece during the Civil War. Known

for its reliability and accuracy, the 3-inch Ordnance rifle was fielded by the artillery branches of both armies. Crafted

from hammer-welded, machined iron the ordnance rifle typically fired 8- or 9-pound shells, as well as solid shot, case, and

canister. Due to the manufacturing process involved, Union-made rifles tended to perform better than Confederate models. (Center)

A Union battery of 20-pounder Parrott rifles in the field. Designed by Robert Parrott of the West Point Foundry (NY), the

Parrott rifle was deployed by both the US Army and US Navy. Parrott rifles were produced in 10- and 20-pounder models for

use on the battlefield and as large as 200-pounders for use in fortifications. Parrotts were easily distinguished by

the reinforcing band around the breech of the gun. (Right) An African-American soldier guards a 12-pounder Napoleon.

The 12-pounder Napoleon Light, as it was also known, was the most widely used smoothbore field cannon used during

the conflict. Designed and named for the French Emperor Napoleon III, the Napoleon was the workhorse gun of the Civil War

artillery. Cast of bronze, the smoothbore Napoleon was capable of firing a 12-pound solid ball, shell, case shot, or canister.

Both sides deployed this versatile gun in large numbers.

| The highly coveted Union field artillery, Napoleon |

|

| Union Model 1857 12-pounder Napoleon gun-howitzer |

Model 1857 12-pounder Napoleon Light Field Gun

The M1857 Napoleon Light, employed in mass numbers by both the

Union and Confederate armies, was the most widely used artillery piece during the Civil War. While the gun was the

most popular, common, and deadly field piece, as a smoothbore, it also subjected the infantry lines to devastating canister

at close range. Developed under the auspices of Louis Napoleon of France, it first appeared in the United States inventory in

1857. In the North, the smoothbore Napoleon was officially designated the "light 12-pounder gun". A Napoleon fired a 12.3

lb projectile and had a maximum effective range of approximately 1,600 yards. Union Napoleons had a slight swell at the muzzle

(Confederate model had no pronounced swell) of the 4.62 inch bore. The barrel with its carriage weighed 2,445 pounds,

light enough to be hauled by men for short distances, however, the usual method of transportation was by a six-horse team

with a driver aside one of each pair of horses.

The Confederacy produced numerable Napoleons, the majority out of bronze.

Confederate made pieces were included iron variants with a band-reinforced breech. The copper that was used in manufacturing

the bronze Napoleons at the famous Tredegar Iron Works of Richmond, Virginia, came primarily from one source: The Ducktown

mines near Chattanooga, Tennessee. Each Napoleon produced by Tredegar, and presumably most other foundries, required over

1000 pounds of copper. At the recommendation of General Robert E. Lee, bronze cannons that fired lighter shot, such as the

6-pounder, were melted down and rebuilt as Napoleons, which were more effective weapons.

Unfortunately for the Confederacy, the Ducktown mines were captured in November

of 1863 by Union forces. This ended bronze Napoleon production in the South, but this did not end Napoleon production,

however. In 1864, Tredegar started to produce iron Napoleons. These were manufactured in a similar fashion as the Parrott

rifles, out of cast iron with wrought iron reinforcing bands. While 120 of these guns were produced by the South before the

end of the war, this method of manufacturing had its disadvantages.

Artillerymen favored bronze Napoleons because their barrels were stronger

and safer than guns made of iron. Bronze pieces had a comparatively lower rate of muzzle bursting incidents when

fired, thus minimizing casualties to the crew. A Napoleon was able to

fire all of the four basic types of ammunition. The solid shot, shell, and case rounds were all spherical and were used against

enemies at distances greater than 600 yards. For shorter distances the gun was loaded with canister, which turned it into

a giant shotgun with lethal effects. Firing canister, the Napoleon probably inflicted more casualties than all other Civil

War era artillery pieces combined.

| Confederates made 6 variants of the Napoleon |

|

| Confederate 1857 12-pounder Napoleon Light |

Model: 1857 12-pounder "Napoleon" Light

smoothbore gun-howitzer

Class: Field artillery, light

Type: Smoothbore gun-howitzer

Manufactured: USA and CSA; 1857 to 1863

Tube Composition: Bronze or cast iron

Bore Diameter: 4.62 inches

Standard Powder Charge: 2.5 lbs. Black Powder

Projectiles: 12 lb. solid shot, spherical case, common shell,

canister

Muzzle Velocity: 1,485 fps

Effective Range (at 5°): 1,619 yards

Tube Length: 66 inches

Bronze Tube Weight: 1,227 lbs.

Iron Tube Weight: 1,249 lbs.

Total Weight (Gun & Carriage): 2,350 lbs.

Carriage Type: No. 2 Field Carriage (1,125 lbs.), 57" wheels

Horses Required to transport: 6

Production: approx. 1100

Cost in 1861 Dollars: $490(US) $ 565(CS)

Cost in 1864 Dollars: $614(US) $1840(CS)

Notes: Named after French Emperor Louis Napoleon III

Model 1861 3-inch Ordnance Rifle

The Model 1861 3-inch Wrought Iron rifle, aka Ordnance Rifle, was the most

common rifled field piece on the battlefield.

Originally known as the "Griffen Gun," after its designer, John Griffen,

the 3-inch Ordnance Rifle was manufactured at the Phoenix Iron Company in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, and it was adopted by

the Federal Ordnance Department in early 1861. The design of this rifle, soon a favorite with artillerists in both armies,

is recognized by the complete absence of any discontinuities in the surface of the gun. It was also a major step forward in

material, being made entirely of wrought iron.

To manufacture the Ordnance Rifle,

strips of wrought iron were hammer-welded in criss-crossing spiral layers around a mandrel; this was then bored out and the

finished product lathe turned into shape. Though time consuming and expensive to produce, the result was a singularly

tough and accurate weapon. Less precise machining and lower-grade iron yielded their Confederate counterparts more imperfections.

While the Napoleon was the weapon of choice for short-range fighting,

the Ordnance Rifle was valued for its long range accuracy. A one lb charge of gunpowder could accurately propel a 10 lb elongated

shell a distance of 2,000 yards at only 5 degrees of elevation. Longer distances, but less accuracy, could be achieved with

higher elevations. Artillerymen preferred this piece because it did not have the tendency to explode upon firing as cast iron

cannon did. This gun is one-hundred pounds lighter than the 10 pdr. Parrott Rifle (800 lbs to the Parrott's 900) which made

it highly mobile. For this reason, it was the preferred weapon of the fully mounted Horse Artillery.

|

| Canister Shot |

The North produced more than 1,000 3-inch Ordnance Rifles during the war

at a cost of approximately $350 each, and were considered prized captures by the South.

The original design was patented in 1855 and was not quite what we know

as the ordnance rifle; there was an evolutionary process both in achieving the final smooth profile of the piece, and the

wrought iron, wound and welded in criss-crossing spirals in the original patent, was apparently done in sheets or plates for

the final form of the gun. The Ordnance Rifle was manufactured at the Phoenix Iron Company in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania.

It was adopted by the Federal Ordnance Department in early 1861. Other versions of this weapon were produced in 1862 and 1863

by different companies, but this is the only weapon officially known as the Ordnance Gun. The Confederates also produced their

own version of this gun.

This weapon could accurately fire Schenkl and Hotchkiss shells approximately

2,000 yards at five degrees elevation, using a one pound charge of powder. The Hotchkiss shell was the most common projectile

fired from the Model 1861. It was designed by Benjamin and Andrew Hotchkiss as a three piece shell - nose (containing the

powder chamber), sabot (soft lead band fitting into an intention in the middle of the shell), and an iron forcing cup at the

base (which forced the lead sabot to expand upon firing).

The other shell for this rifle was the Schenkl. This was a cone shaped projectile

which employed ribs along the taped base. The sabot was made of papier-mâché' which was driven up the taper by the force of

the gas produced upon firing. The sabot then expanded and caught the rifling in the tube.

| 3-inch Ordnance Rifle |

|

| 3-Inch Wrought Iron Rifle |

This gun was sometimes erroneously referred to as a "Rodman." The process

used by Thomas Rodman in casting the Columbiads was not used in producing the wrought iron barrel of the Ordnance gun. Rodman

was also absent during research and development, as well as final design and production of this gun.

Model: 3-Inch Wrought Iron Rifle

Class: Field artillery, light

Type: Rifled-gun

Manufactured: USA; 1861 to 1865

Tube Composition: Wrought iron

Bore Diameter: 3.0 inches

Rifling Type: 7 rifle grooves

Standard Powder Charge: 1 lb. Black Powder

Projectiles: 10 lb. Bolts, 8 to 9 lbs. Hotchkiss or Schenkel

shells

Muzzle Velocity: 1,215 fps

Effective Range (at 5°): 1,850 yards

Tube Length: 73 inches

Tube Weight: 816 lbs.

Total Weight (Gun & Carriage): 1,720 lbs.

Carriage Type: No. 1 Field Carriage (900 lbs.), 57" wheels

Horses Required to Pull: 6

No. in North America: approx. 1000+

Cost in 1861 Dollars: $330 (US)

Cost in 1865 Dollars: $450 (US)

Invented By: John

Griffen in 1855

US Casting Foundry: Phoenix Iron Company, Phoenixville PA

CS Casting Foundry: Tredegar

Iron Works, Richmond VA (CS castings were known as: 3-inch Iron Field

Rifles)

Notes: Lightest and strongest rifled tube. Sometimes incorrectly

referred to as a Rodman gun.

Model 1841 6-pounder Smoothbore Field Gun

Model 1841 6-pounder Gun was the workhorse of the Mexican-American War.

Although considered obsolete by 1861 standards, battlefield necessity pressed this gun into service immediately.

The 6-pounder field gun was a lightweight, mobile piece that was a favorite

of the field artillery in the first half of the nineteenth century. This popular workhorse of the Mexican War era was regarded

as obsolete by the Union army, but was still heavily employed by the Confederate army midway through the conflict. Field guns were produced in 6-pounder (3.67 inch bore), 9-pounder (4.2 inch bore),

and 12-pounder (4.62 inch bore) versions. Although some older iron weapons were pressed into service, and the Confederacy

produced some new iron field guns, most of those used on the battlefields were of bronze construction.

The 6-pounder field gun was well represented by bronze Models of 1835,

1838, 1839, and 1841 early in the war. Even a few older iron Model of 1819 weapons were pressed into service. Several hundred

were used by the armies of both sides in 1861. But in practice the limited payload of the projectile was seen as a shortcoming

of this weapon. From mid-war on, few 6-pounders saw action in the main field armies because, in early 1863, Robert E. Lee

sent nearly all of the Army of Northern Virginia's obsolete bronze 6-pounder guns to Tredegar to be melted down and recast

as Napoleons.

| Model 1841 6-pounder Gun |

|

| Model 1841 6-pounder Smoothbore field gun |

The larger 9- and 12-pounders received insignificant representation in the field. While

the 9-pounder was still listed on Ordnance and Artillery manuals in 1861, very few were ever produced after the War of 1812

and only scant references exist to Civil War use of the weapons. The 12-pounder field gun appeared in a series of models replicating