|

|

Civil War Small Arms and Firearms: A Photographic History

Union and Confederate Handguns, Muskets, and Edged Weapons

Civil War Revolvers, Rifles, and Carbines

Union

and Confederate Sidearms, Pistols, Swords, Sabers, and Knives

Introduction

| Civil War guns and firearms |

|

| Civil War small arms, from pistols to rifles to edged weapons |

During the American Civil War

(1861-1865) small arms were the dominant weapons on the battlefield. The firearm known as the musket, applied with Napoleonic

Tactics of the era, accounted for more deaths during the conflict than all other weapons combined. While the rifle killed

and mortally wounded on the nation's killing fields, it also maimed, disfigured, and disabled both Northern and Southern men

and boys alike. While the smoothbore and rifle muskets directly killed tens of thousands, the majority of battle deaths were

caused indirectly by disease from wounds that the soldiers sustained.

A casualty is a soldier lost

through death, wounds, injury, sickness, internment, capture, or missing in action. "Casualty" and "fatality"

are not interchangeable terms, and death was only one of the ways that a soldier could become a casualty. In practice,

officers would usually be responsible for recording casualties that occurred within their commands. If a soldier was

unfit for combat due to one of the above conditions, the soldier would be considered a casualty. This means that one

soldier could be marked as a casualty several times throughout the course of the war.

Most casualties and deaths in the Civil War were the result of non-combat-related

disease. For every three soldiers killed in battle, five more died of disease. The primitive nature of Civil War

medicine, both in its intellectual underpinnings and in its practice in the armies, meant that many wounds and illnesses were

unnecessarily fatal.

Our modern conception of casualties also includes those who have been

psychologically damaged by warfare. This distinction did not exist during the Civil War. Soldiers suffering from

what is currently recognized as shell shock (battle fatigue) and post-traumatic stress disorder were uncatalogued,

uncared for, and, if they survived the war, discharged into an unprepared society.

Approximately one in four soldiers that went to war never returned home. At the outset of

the war, neither army had mechanisms in place to handle the amount of death that the nation was about to experience. There

were no national cemeteries, no burial details, and no messengers of loss. The largest human catastrophe in American

history, the Civil War forced the young nation to confront death and destruction in a way that has not been equaled before

or since. Recruitment was highly localized throughout the war.

Regiments of approximately one thousand men, the

building block of the armies, would often be raised from the population of a few adjacent counties. Soldiers often marched

into battle alongside their brothers, fathers, nephews, and neighbors, and when enemy shot and shell mowed down the ranks,

it often meant that the local community had lost many or all of its men. For the predominately rural South,

the nature of recruitment meant that a

battlefield disaster could wreak havoc on the home community for many years beyond the conflict.

| Civil War Guns and Weapons |

|

| Civil War battles with most casualties |

The standard weapon used by both sides during the Civil War

was a muzzle-loading .58 caliber rifle musket: the Union preferred the Springfield version, while the Confederacy the Enfield.

It was a good weapon but its loading method limited its efficiency and at times made it dangerous. In the heat of battle,

soldiers sometimes forgot whether they had rammed the weapon and would therefore recharge it. At other times the piece

would misfire, and, thinking that the weapon had fired, the soldiers would proceed and reload. Unfortunately, it was

fairly easy to ram several charges into the muzzle. After the battle of Gettysburg, for example, of the 27, 574 weapons

collected from the battlefield, approximately 6,000 were found to be properly charged, and a staggering 12,000 had three

to ten loads. (One rifle contained twenty-three.) From these figures it was estimated that one-third of the men on

opposing sides of the battlefield were merely spectators during the fight, because they were carrying non-functioning

weapons.

The Civil War witnessed a technological

revolution in weaponry and it was highlighted by a transition in shoulder-fired weapons from smoothbore firearms

that had to be loaded through the muzzle each time a shot was fired to rifled-barrel weapons -- some of which charged at the

breech. While most of the new rifle-muskets still had to be reloaded after each shot, repeating weapons such as

the 7-shot Spencer and 16-shot Henry rifles and carbines were developed as well. Unfortunately for the Civil War soldier,

tactics did not advance as quickly as technology. Napoleonic tactics, the linear troop formations adopted from earlier in

the century, were now combined with more accurate, faster-firing weapons that were capable of producing catastrophic

casualties.

The Confederacy, whose industrial base was weaker than

the Union's, accomplished a great feat by establishing a viable arms-manufacturing capability in short order. The North's

industrial machine also swung into high gear to produce massive quantities of weapons and ammunition.

Agents from both the Union and the Confederacy scoured the shelves of European arms-dealers to ensure that their armies had

an adequate supply of weapons. Most Confederate infantrymen favored the English-manufactured Enfield, known also as the Enfield

Pattern 1853 rifle musket, while Union soldiers preferred the U.S. Model 1861 Springfield rifle.

| Civil War guns and weapons |

|

| Civil War revolver, rifle, and sword |

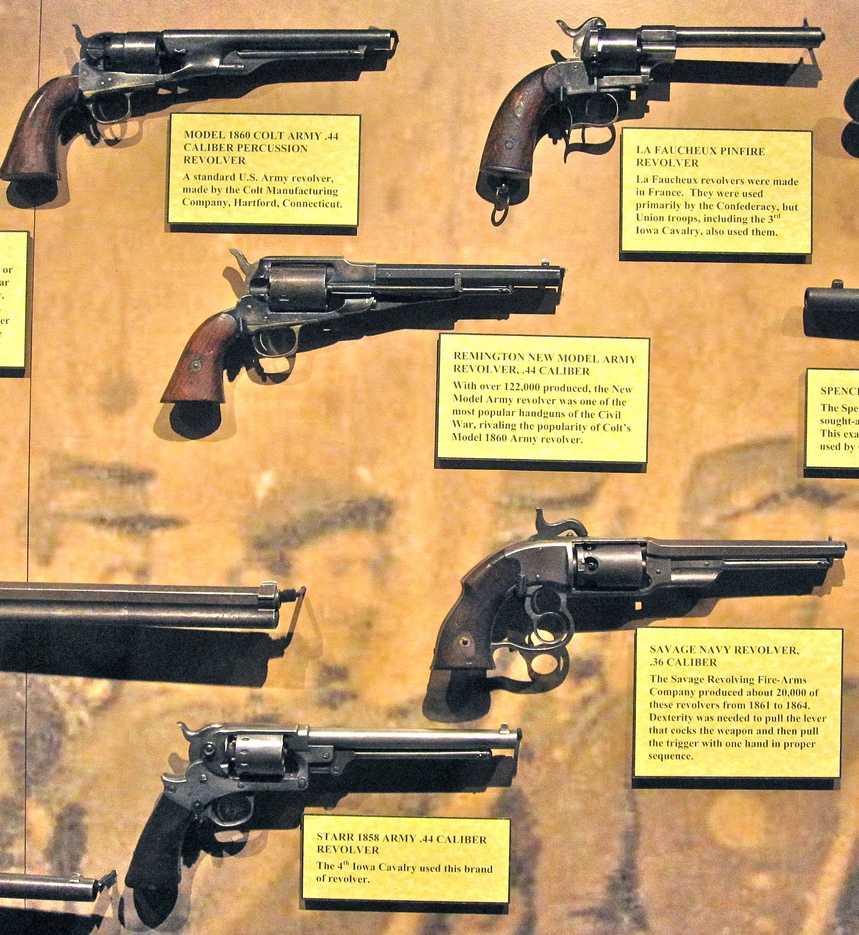

(Above) Civil War cavalry accoutrements.

This Civil War display of firearms represents the Union issued weapons to most cavalry during ca.

1863-65. Many soldiers, at their own expense, however, also carried additional revolvers into the fray. By 1863, a veteran

trooper could be seen with as many as 4 revolvers, 1 carbine, and 1 saber. The cumbersome edged weapons, lacking in this

display, were shed for more practical pieces such as extra sidearms. Confederate cavalrymen, on the other hand, lacking

carbines, were known to ride their favorite mount with 3 or 4 pistols (perhaps 4 six shooters), 1 shotgun, 1 rifle, and 1

saber. The soldier could discharge as many 24 rounds before reloading his small arms and revolvers--an appreciated advantage

for any horseman.

Evolution of Weapons

| Civil War guns |

|

| Civil War rifles |

Flintlocks were developed during the early 1600s and replaced several other

cumbersome arrangements. This system employed a piece of flint (a hard quartz-like stone) that was clamped into the top of

the musket hammer. When fired, the hammer fell forward and drove the flint into a vertical, spring-held piece of steel.

The steel served a dual purpose: when not being actively used, it was a cover for a small "pan" that contained a priming charge

of about ten grains of black powder. In operation, when the flint struck the steel, the steel snapped back exposing the priming

charge while a shower of sparks fell into the pan. The sparks ignited the priming charge and passed fire through a small hole

in the side of the barrel that communicated with the main powder charge in the barrel. Although the system functioned well

it was prone to misfires. The failure of the sparks to ignite the priming charge, or a damp or even lost priming charge

were just some of the reasons the flintlock system was less than adequate.

(Right) Civil War Rifles and Carbines. From top to bottom: Colt Model 1853

rifle used by sharpshooters, Sharps carbine, and Burnside carbine--invented by Union General Ambrose Burnside.

The percussion system of priming that used the copper percussion cap is

popularly credited to the Englishman, Joshua Shaw, who secured a U.S. patent in 1822. For shoulder arms, the percussion cap

resembled a tiny "top hat" and was about the size of a modern pencil eraser. Pistol caps were usually straight-sided without

the "brim" and were smaller still. The interior of the percussion cap had a small deposit of fulminate of mercury or another

"salt" formed by dissolving a metal in acid. The correct formula produced a substance that exploded when it received a sharp

blow. After loading the weapon with powder and ball or an externally primed cartridge, a percussion cap was placed by hand

onto a hollow tube, called a cone or nipple, at the breech end. With the percussion cap, there was no priming powder to blow

away or get wet, and the frizzen would not fail to spark during humid conditions. The vent hole (the hole that the spark from

the initial explosion traveled through to ignite the powder in the barrel) was not as prone to become fouled with gun powder,

thus eliminating the "flash in the pan" that occurred when the powder in the priming pan ignited but the powder in the barrel

did not.

The percussion system of priming was more reliable and easier to clean and to use. Dragoon units

in the U.S. Army were armed with percussion weapons from the creation of the unit in 1833. Although the infantry was slower

to adapt, it was, however, armed with percussion weapons by the Civil War--but some of the volunteer units still used

flintlocks during the beginning of the conflict.

| Civil War weapons of the artillery soldier |

|

| Weapons carried by the Civil War artillerist |

| Civil War guns, firearms and weapons |

|

| Names of the parts of a musket |

(Right) Civil War artillery accoutrements. Sword and short sword with respective scabbards, sword

without scabbard, revolver, and rifle. In 1864, to compensate for infantry attrition, most Union heavy artillery

regiments were reassigned as provisional infantry regiments and sent into action. Accused of cushy garrison duty until '64,

many of the artillerists had never fired a shot in combat. They were now confronted with veteran Confederate infantrymen

during the fierce Wilderness Campaign to the trenches of Petersburg, and as a result of their baptism of fire, most of the

H.A. units received all of their casualties in the last 10 months of the war. Fighting was bloody for the cannoneers, and

several regiments suffered 1,000 or more casualties in those 10 months.

| Popular Civil War guns and rifles |

|

| Widely used Civil War guns |

| Civil War era Napoleonic Tactics |

|

| Rank and File Formation employed, aka as Line Formation |

For centuries, men had known that by cutting spiraled grooves, known as

rifling, inside a musket barrel to impart spin to the bullet, they could increase its range and accuracy. Hunting weapons

were usually rifled and some eighteenth-century armies contained special rifle regiments. But the smoothbore remained the

principal infantry weapon until the 1850s, because a bullet large enough to "take" the rifling was difficult to ram

down the barrel of a muzzle-loading weapon. After a rifle had been fired a few times, the residue from the black powder concealed

the grooves and made the gun extremely difficult to load without cleaning. Since rapid loading and the reliability of repeated

and prolonged firing were essential to the weapon, the rifle could only be used for specific or special purposes. This dilemma, however, was solved by the creation of the "Minie ball" in the 1840s.

Named after its inventor, French Army officer Claude-Etienne Miniť, the Miniť ball was created in 1847, and the Miniť rifle

in 1849.

The Minie ball was elongated with a base that expanded to "take" the

rifling as it traveled through the barrel. The expanding bullet would also clean the grooves in the rifle as it exited

the weapon. Said expansion would continue once it reached its intended target. The Minie ball caused a small entrance

but rather large exit wound, thus inflicting additional pain and suffering than the standard ball that preceded it. Minie

balls became standard issue during the Civil War.

This development revolutionized military tactics. The effective range of

the smoothbore musket was 50-100 yards, and because of its poor accuracy and limited range, fighting tactics with smoothbores

required soldiers to stand shoulder to shoulder in lines. One line, or rank, would fire, fall back, reload, while

the line of infantrymen behind them would follow suit. In another formation, the soldiers assembled in four lines

and fired concurrently. The objective was to unleash a large quantity of lead towards the target simultaneously in order

to increase the probability of a hit. Infantry charges, notwithstanding, were employed with this tactic because with

the smoothbore's restrictive range of fire, a defending army would only have sufficient time

to discharge a couple of aimed shots before the opposing army advanced at double quick with fixed bayonets.

The rifle's effective range

caused the Union and Confederate armies to suffer massive casualties as they continued applying the traditional Napoleonic

Tactics. With it's maximum range of 1,000 yards and an effective range of 400 yards, the rifle had rendered the tactics obsolete.

The old smoothbore strategy was no longer effective because the infantry charge, such as Pickett's Charge, was now cut

to pieces prior to reaching enemy lines. Although Union regiments

were not sufficiently armed with rifles when the Civil War commenced, some infantry units entered the field equipped

with the Springfield or Enfield, and enjoyed the initial advantage of confronting Johnny Reb and his smoothbore.

Civil War small arms capabilities. |

Weapon

type |

Caliber |

Bayonet |

Magazine

capacity |

Rounds

carried |

Rate of

fire/min. |

Revolver,

Colt |

.44 ball |

no |

6 |

24 |

6 |

Revolver,

Remington |

.44 ball |

no |

6 |

24 |

6 |

| Henry rifle |

.44 rimfire |

no |

16 |

50 |

16 |

Smith

carbine |

.50 linen

cartridge |

no |

1 |

40 |

8 |

Hall

carbine |

.51 paper

cartridge |

no |

1 |

40 |

8 |

Sharps

carbine |

.52 paper

cartridge |

no |

1 |

40 |

8 |

Starr

carbine |

.54 paper

cartridge |

no |

1 |

40 |

8 |

841

rifle |

.54 paper

cartridge |

saber-

type |

1 |

40 |

3 |

| Austrian rifle |

.54 paper

cartridge |

no |

1 |

40 |

3 |

Burnside

carbine |

.54 brass

cartridge |

no |

1 |

40 |

10 |

Spencer

carbine |

.56-56

rimfire |

no |

7 |

40 |

14 |

Joslyn

carbine |

.56-56

rimfire |

no |

1 |

40 |

8 |

Enfield

musket |

.577

paper

cartridge |

angular |

1 |

40 |

3 |

Springfield

musket |

.58 paper

cartridge |

angular |

1 |

40 |

3 |

Altered

muskets |

.69 paper

cartridge |

angular |

1 |

40 |

3 |

| Shotguns |

various

M.L. |

no |

1 or 2 |

unknown |

3 |

(Above) Comparison of most widely used small arms during the Civil

War.

| Widely used Civil War pistols and handguns |

|

| Common Civil War revolvers and sidearms |

Muzzleloaders vs. Breechloaders

Muzzle-loaders were weapons that required the round to be charged and

then rammed down the muzzle or barrel of the weapon. This type of loading was slow and cumbersome. Breech-loaders, however, opened

at the breech or the rear of the weapon and the round was inserted directly into the firearm without the use of a rammer. Compared

to the muzzle-loader, the breech-loader fired rapidly but its imperfections proved problematic. While gases, produced

by firing, escaped through a gap in its breech causing soldiers to suffer burns to the face, it also induced the weapon to malfunction as the barrel heated with rapid use. Dragoons, nevertheless, were

armed with breech-loaders in the early 1840s, but as a consequence of said problems, the musketoons replaced it in

the late 1840s. The musketoon, although a muzzle-loader, was a percussion weapon.

In the 1850s, several inventors developed

copper cartridges or other devices that eliminated the problems associated with escaping gases, yet the Army was reluctant

to adopt breech-loaders because of unproven technology, only to reverse its decision and reenter the rifle to active

service late in the Civil War.

Revolver

The most prolific maker of handguns during the Civil War was Samuel

Colt. During the conflict his Hartford, Connecticut firm produced nearly 150,000 .44 caliber six-shot revolvers (the 1860

"New Model Army"). The vast majority of them went to the Union war effort, but Colt sold arms to all buyers until a few days

after the firing on Ft. Sumter. These guns were durable and powerful. From 16 yards, a bullet from a Colt Army revolver penetrated

seven white pine boards, each 3/4" thick, separated by one inch of dead space between

them. Colt also manufactured the "Navy" model revolver but in .36 caliber only. Introduced in 1851, the Navy

model, a lighter revolver, was widely available in the South, and a favorite arm of Confederate horsemen. Before the war's

end, 185,000 Navy revolvers had been produced.

The Colt Army Model 1860 was the most mass produced and widely used handgun in the Civil War

by both the Union and Confederacy. There were several models and variations produced of this basic model as well as other

Colt handguns that were employed. Because the Union military preferred the

lighter Colt 1851 Navy, it purchased many of the handguns for both Army and Navy personnel.

Colt supplied the Union with Army Model 1860 a .44 caliber six shooter that

enabled the average soldier an effective range of 20 to 50 yards. The Confederacy preferred the M1851 Colt Navy

Revolver with its 1,000 foot per second velocity. Remington, primary competitor to Colt, sold the Model 1858, which had a

quick reload time.

While most Civil War pistols were

single action revolvers, several hundred thousand were produced by Colt, with half as many made by Remington, and the

next prolific manufacturer, producing approximately 25,000, went bankrupt shortly after the conflict began. Many additional

manufacturers strived to make their fortunes in the revolver business but with mixed results. Colt, however, had filed

lawsuits against numerous companies and upstarts in the North for patent infringement. And Southern attempts at

reproducing the Colt was met with mixed results, and production was considered negligible.

Except for Smith and Wesson, these revolvers were tediously loaded with

either combustible paper cartridges or with loose powder and ball. Both methods inserted the powder and bullet from the front,

and a rammer was built into the gun to swage the bullet into position. The swaging prevented the bullet from falling

out while the gun recoiled when fired. Lastly, a percussion cap was individually fitted

to the back of the cylinder with one required for each of the five or six chambers.

Because reloading could take minutes, two

or more spare cylinders were generally carried pre-loaded for an advantage. Instead of losing critical seconds during

the reloading process, the spare cylinders would be exchanged quickly for rapid firing. Civil

War guns fired an older powder, now called Black Powder, that creates clouds of smoke. During the era the propellant

was known as gunpowder, while the cloud (or smoke) was referred to as gunsmoke. As six shots rapidly fired from

a revolver, or a line of muskets discharging in concert, on a windless day could create a smoke cloud so dense as to

obscure the targets from the shooter.

The .36 caliber (.375–.380 inch) round lead ball weighs 80 grains and, at a velocity of

1,000 feet per second, is comparable to the modern .380 pistol cartridge in power. Loads consist of loose powder and ball

or bullet, metallic foil cartridges (early), and combustible paper cartridges (Civil War era), all combinations being ignited

by a fulminate percussion cap applied to the nipples at the rear of the chamber. Sighting consists

of a bead front sight with a notch in the top of the hammer, as with most Colt percussion revolvers.

The Colt .44 caliber Army had a six-shot, rotating cylinder, and fired a 0.454-inch-diameter

(11.5 mm) round lead ball, or a conical projectile, that was propelled by a 30-grain charge of black powder ignited by a copper

percussion cap that contained a volatile charge of fulminate of mercury (a substance that explodes upon impact). The percussion

cap, when struck by the hammer, ignited the powder charge. When fired, balls had a muzzle velocity of nearly 900 feet

per second.

"The cylinder was a 'rebated cylinder,' meaning that the rear of the cylinder was turned to a

smaller diameter than the front. The barrel was rounded and smoothed into the frame, as was the Navy Model. The frame, hammer,

and rammer lever were case-hardened, the remainder blued; grips were of one-piece walnut; and the trigger guard and front

grip strap were of brass while the backstrap was blued."

Colt used the engraved cylinder

as a form of patent protection, because many reproductions were being manufactured abroad as well as at home. Knowing

that it was not an inferior replica, the engraving proved a welcomed

scene to the soldier who held the genuine while dashing into the fray.

| Civil War firearms, handguns, and side arms |

|

| Model 1860 Colt Army revolver .44 caliber |

| Civil War guns, pistols, revolvers, and weapons |

|

| Model 1851 Colt Navy revolver .36 caliber |

| Characteristics of widely used Civil War weapons |

|

| Capabilities of the most widely employed small arms and firearms during the Civil War |

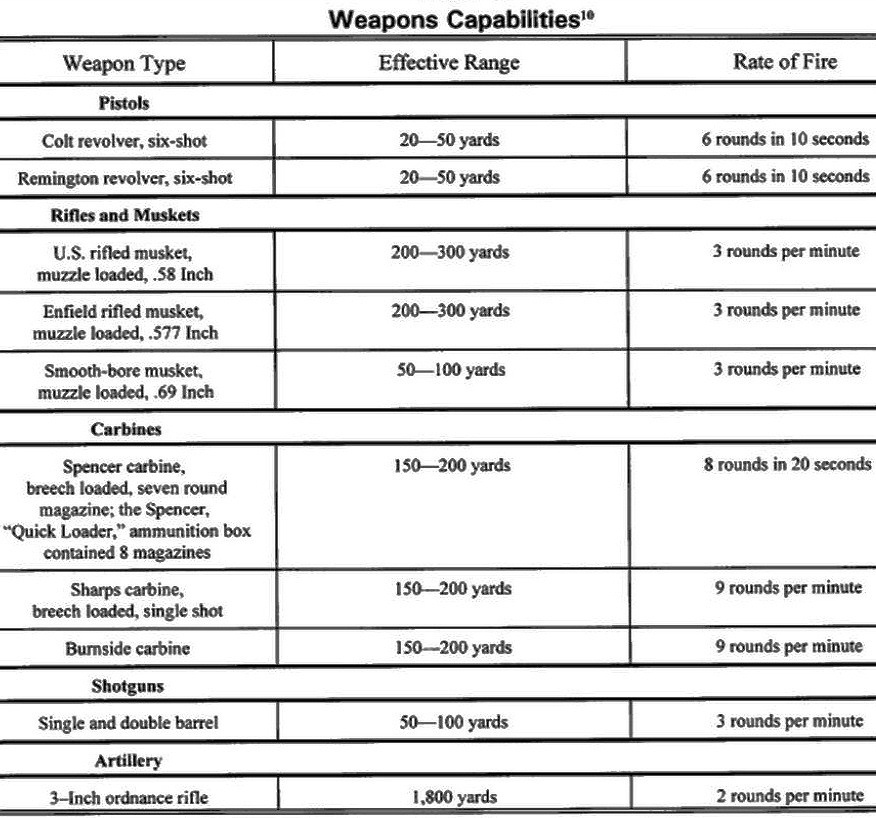

(Above) With the exception of the 3" Wrought Iron Gun (or Ordnance Rifle),

these small arms -- whether referred to as handguns, pistols, sidearms, guns, or firearms -- were the mainstay of both Union

and Confederate infantry and cavalry, and were responsible for the majority of the battlefield deaths during the four year

Civil War.

Rifles

The most popular rifle used in the Civil War was the U.S. Model 1861 Springfield rifle musket.

This rifle was known for its range, accuracy and reliability. At a weight of 9 lbs and an effective range of 200 to 300

yards, it could be loaded quickly and was easier to carry than previous rifles. A trained soldier could accurately fire three

rounds per minute. The rifle, and similar new guns, literally changed the way wars were fought. Because the enemy could now

take aim and eliminate soldiers at great distances, the time-honored attack method of massing soldiers for firepower and charges

became a high risk maneuver. By the war's end, both sides favored trench warfare with a greater emphasis on long-range weapons

-- a mindset that future generals would adopt during warfare.

| Civil War rifles and guns |

|

| Civil War firearms and small arms |

(Above) From top to bottom: Sharps Target Rifle .52 caliber, Harpers Ferry

Rifle Model 1855 .58 caliber, Harpers Ferry "Mississippi Rifle" Model 1841 .54 caliber, Fayetteville "Short" Rifle Musket

(Confederate manufacture) .58 caliber, Enfield "Short" Rifle Musket .577 caliber, Merrill Breech-loading Rifle .54 caliber,

Mounted Rifle .58 caliber, and Sharps Rifle .52 caliber.

Springfield Smoothbore Musket

|

| Model 1842 Springfield smoothbore musket |

The U.S. Model 1842 Musket was a .69 caliber smoothbore musket manufactured

and used in the United States during the 19th Century. It is a continuation of the Model 1816 line of muskets but is generally

referred to as its own model number rather than just a variant of the Model 1816.

The Model 1842 was the last U.S. smoothbore musket. Many features that had

been retrofitted into the Model 1840 were standard on the Model 1842. The Model 1842 was the first U.S. musket to be produced

with a percussion lock, though most of the Model 1840 flintlocks were later converted to percussion locks before reaching

the field. The percussion cap system was vastly superior to the flintlock, being more reliable and resistant to inclement weather.

(Right) The first percussion U.S. military musket and also

the first with interchangeable parts, the Model 1842 was widely used during the Mexican-American War (1846-48) but saw limited

action during the Civil War. Identifiable by it's split front band and endcap, high spur hammer, flat buttplate and lack of

rear sight.

With all Model 1816 derivatives,

the Model 1842 has a .69 caliber barrel that was 42 inches in length. The Model 1842 had an overall length of 58 inches

and a weight of 10 lbs.

A great emphasis was placed on manufacturing processes for the Model 1842.

It was the first small arm produced in the U.S. with fully interchangeable (machine-made)

parts. Approximately 275,000 Model 1842 muskets were produced at the Springfield and Harper's Ferry armories between 1844

and 1855. Model 1842 muskets were also manufactured in small quantities by private contractors. Some were made by A.H. Waters

and B. Flagg & Co, both of Millbury, Massachusetts. These were distinguished by having brass furniture instead

of iron. A.H. Waters went out of business due to a dearth of contracts in New England, and Flagg entered into a partnership

with William Glaze of South Carolina. They relocated the machinery to the Palmetto Armory in Columbia, South Carolina. Instead

of “V” over “P” over the eagle’s head, these guns were usually stamped “P” over

“V” over the palmetto tree. Most of the output of the Palmetto Armory went to the state militia of South Carolina.

There were only 6,020 1842 type muskets produced on that contract and none were made after 1853.

Comparable to the earlier Model 1840, the Model 1842 was produced with an

intentionally thicker barrel than necessary, with the belief that it would be rifled later. As the designers anticipated,

many of the Model 1842 muskets had their barrels rifled later so that they could fire the newly developed Miniť ball. Tests

conducted by the U.S. Army showed that the .69 caliber musket was not as accurate as the smaller bore rifled muskets. Also,

the Minie Ball, being conical and elongated, had much more mass than a round ball of the same gauge. A smaller caliber Miniť

ball could be used to provide as much mass on target as the larger .69 caliber round ball. For said reasons, the Model

1842 was the last .69 caliber musket. The Army later standardized on the .58 caliber Minie Ball, as used in the Springfield

Model 1855 and Springfield Model 1861.

Both the original smoothbore version and the modified rifled version of

the Model 1842 were used in the Civil War. The smoothbore version was produced without sights, as they provided little value

to a weapon that was only accurate to 50 to 75 yards. When Model 1842 muskets were modified to have rifled barrels, sights

were usually added at the time of the rifling.

|

| Model 1861 Springfield rifle musket |

The most widely used weapon during the Civil War, the U.S. Model 1861 Springfield

rifle musket was a single shot, muzzle-loading gun that used the percussion cap firing mechanism. It had a rifled barrel,

and fired the .58 caliber Miniť ball. The first rifled muskets had used a larger .69 caliber Miniť ball, since they had simply

taken .69 caliber smoothbore muskets and rifled their barrels. Tests conducted by the U.S. Army indicated that the .58 caliber

was more accurate at a distance. After experimenting with the failed Maynard primer system on the Model 1855 musket, the Model

1861 reverted to the more reliable percussion lock. The first Model 1861 Springfields were delivered late in that year and

during 1862 gradually became the most common weapon carried by Union infantry in the eastern theater. Western armies were

slower to obtain Springfield rifles, and they were not widely used there until the middle of 1863.

Although rifles were more accurate than smoothbore

muskets, some argued that the weapons could have been manufactured with shorter barrels. The military was still

employing tactics such as firing by ranks, or lines, and feared that shorter barrels would result in soldiers in the rear

line accidentally shooting front rank soldiers in the back of the head. Bayonet fighting was important at this

time, which also made militaries reluctant to shorten the barrels. The Springfield Model 1861 therefore used a three-band

barrel, making it just as long as the smoothbore muskets that it had replaced. The 38-inch-long rifled barrel made it a very

accurate weapon, and it was possible to hit a man sized target with a Miniť ball as far away as 500 yards. To reflect this

longer range, the Springfield was fitted with two flip up sights, one set for 300 yards and the other for 500. Along with

a revised 1863 model, it was the last muzzle-loading weapon ever adopted by the US Army.

|

| Model 1863 Springfield rifle musket |

(Right) The Model 1861 Springfield rifle musket is identifiable by its block rear sight, barrel

bands with retaining springs, curved buttplate and C-shaped hammer. While the similar Model 1863 rifle had a standard S-shaped

hammer, many had no band springs. Both, however, employed the .58 caliber Miniť ball.

Produced by the Springfield Armory between 1863 and 1865, the Model

1863 was only a minor improvement over the earlier model. As such, it is sometimes classified as just a variant of the Model

1861. Equipped with a triangular bayonet, the Model 1861, with all of its variants, was the most commonly used longarm in

the conflict. The Model 1863, however, has the distinction of being the last muzzle-loading longarm produced

by the Springfield Armory.

By the end of the war, approximately

1.5 million Springfield rifle muskets had been produced by the Springfield Armory and 20 subcontractors. Since the South lacked

sufficient manufacturing capability, most of the Springfields in Southern hands

were captured on the battlefields during the war. Many older Springfield rifle muskets, such as the Model 1855 and 1842, were

brought out of storage and used due to arms shortages. Many smoothbore muskets dating to the Springfield Model 1812 returned

to active duty for similar reasons. The old and obsolete weapons, nevertheless, were replaced by newer weapons as they

became available.

|

| British 1853 Enfield rifle musket |

The second most widely used weapon of the Civil War, and the most widely

used weapon by the Confederates, was the British Pattern 1853 Enfield. The

Enfield Pattern 1853 rifle-musket (also known as the P53 Enfield, and Enfield rifle-musket) was a .577 calibre Miniť-type

muzzle-loading rifle-musket, used by the British Empire from 1853 to 1867.

Resembling the Springfield, it was a three-band, single-shot, muzzle-loading

rifle musket, and it was the standard weapon for the British Army for fourteen years. American soldiers appreciated this rifle

because its .577 cal. barrel allowed the use of .58 cal. ammunition used by both Union and Confederate armies. Lacking

adequate production of munitions, Southern soldiers were known to scavenge the Union dead on the battlefield

hoping to locate the precious .58 bullets needed for the next fight. If the Union Springfield was recovered

on the killing fields -- good. But if its interchangeable.58 caliber nuggets were located -- outstanding.

Because without ammunition, both the Enfield and Springfield were reduced to burdensome objects of mere wood

and metal. The demand from both firearms made the .58 caliber the most lethal as well as wanted gauge of the conflict. Originally

produced at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield, England, approximately 900,000 of these muskets were imported during

1861–1865, being used in every major battle from Shiloh onward. Many officers, however, preferred the Springfield muskets

over the Enfield muskets—largely due to the interchangeability of parts that the machine-made Springfields offered.

The Enfield had a stepped flip up sight, which was adjustable from 100–900

yards (1,200 yards in later models) in 100 yard increments. Realistically, though, hitting anything beyond 500 yards

rarely occurred.

|

| Model 1854 Lorenz rifle musket |

The third most widely used weapon of the Civil War was the Model 1854 Lorenz

Rifle. This rifle was invented in 1854 by Austrian lieutenant Joseph Lorenz, and had first seen action in the Second Italian

War of Independence.

The Lorenz rifle was similar in design to the Enfield rifle-musket. It utilized

a percussion lock, was comparable in length, and had three barrel bands, consistent to the Springfield and Enfield. The Lorenz

rifle was originally .54 caliber. A large number were bored out to .58 caliber so that they could use the same ammunition

as the Springfield and Enfield rifle-muskets.

The quality of Lorenz rifles during the Civil War was not consistent. Some

were considered to be of the finest quality, and were sometimes praised as being superior to the Enfield. Others, especially

those in later purchases, were described as horrible in both design and condition. The bored out versions were not consistent

in caliber, ranging from .57 to .59. Many of these poorer quality weapons were swapped out on the battlefield for Enfield

rifle-muskets whenever one became available. The Union purchased 226,924 Lorenz rifles, and the Confederacy bought as many

as 100,000.

| Civil War rifles: Enfield, Springfield, Model 1842 |

|

| The most widely used rifles during the Civil War |

In 1861 a shortage of rifles on both sides forced the Northern

and Southern governments to issue the older smoothbore weapons or purchase weapons from European nations. As the war progressed

most soldiers eventually were armed with rifled muskets, although even late in the war some troops on both sides still carried

smoothbores.

During most of the war the standard infantry weapon was the

.58-caliber rifled musket, adopted by the U.S. Army in 1855 to replace the .69-caliber smoothbore musket. The new infantry

arm was muzzle loaded, its rifled barrel taking a hollow-based cylindroconical bullet slightly smaller than the bore. The

loading procedure required the soldier to withdraw a paper cartridge (containing powder and bullet) from his cartridge box,

tear open one end with his teeth, pour the powder into the muzzle, place the bullet in the muzzle, and ram it to the breech

using a metal ramrod. A copper percussion cap was then placed on a hollow cone at the breech. To fire the weapon the hammer

was cocked, and when the trigger was pulled the hammer struck the cap and ignited the powder charge. Each soldier was expected

to be capable of loading and firing three aimed shots per minute. Although the maximum range of a rifled musket was considered

to be 1,000 yards, actual fields of fire were often very short, the emphasis of musketry fire resting upon volume at close

range rather than accuracy at long distance.

The basic ammunition allowance for each infantry soldier was

40 rounds in a leather cartridge box. When a large action was expected, 20 additional rounds were issued to each soldier,

who placed them in his uniform pockets or knapsack. In addition, 100 rounds per man were held in the brigade or division trains

and 100 rounds in the corps trains.

Officers generally carried both single- and multiple-shot handguns.

Although the types of handguns used by both sides were innumerable, two of the most

common were six-shot revolvers produced by Colt and Remington, both in .36- and .44-caliber. Union cavalrymen were initially

armed with sabers and handguns, but soon added breech-loading carbines. In addition to Sharps and Spencer carbines, dozens

of other types of breech-loaders, from .52- to .56-caliber, were issued. Confederate cavalrymen were generally armed

with a wide variety of handguns, shotguns, muzzle-loading carbines, or captured Federal weapons.

| Civil War handguns, pistols, rifles, and sidearms |

|

| Civil War carbines, rifles, revolvers, and small arms |

(Above) From top to bottom: Richmond Carbine (Confederate manufacture) .58

caliber, Smith Breech-loading Carbine .50 caliber, Sharps Breech-loading Carbine Model 1859 .52 caliber, Merrill Breech-loading

Carbine .54 caliber, Gallagher Breech-loading Carbine .50 caliber, Burnside Breech-loading Carbine .54 caliber. Revolvers

- top row from left to right: Smith & Wesson Revolver Model #2 .32 caliber, Colt Revolver Model 1851 Navy .32 caliber,

Colt Revolver Model 1860 Army .44 caliber. Revolvers - bottom row from left to right: Remington Revolver Model 1861 Army .44

caliber, Kerr Double Action Revolver .44 caliber, and Adams Revolver .36 caliber.

Typical Civil War Small Arms

| Civil War revolvers |

|

| Civil War Remington revolvers |

|

Weapon |

Effective Range (in yards) |

Theoretical Rate of Fire (in rounds/minutes) |

| U.S. rifled musket, muzzle-loaded, .58-caliber |

400-600 |

3 |

| English Enfield rifled musket, muzzle-loaded, .577-caliber |

400-600 |

3 |

| Smoothbore musket, muzzle-loaded, .69-caliber |

100-200 |

3 |

Most Widely Used Guns in the

Civil War

◾.32 caliber Colt 1849

◾.32 caliber S&W No. 2

◾.36

caliber Colt 1851

◾.36 caliber Colt 1862

◾.44 caliber Colt 1860

◾.44 caliber Remington

◾.58

caliber Springfield Musket

◾.577 caliber Enfield Musket

◾.58 caliber Lorenz Musket

◾.69 caliber Musket

◾Burnside Carbine

◾Colt Walker &

Dragoon

◾Confederate Pistols, Carbines, and Shotguns

◾Henry Rifle 1860

◾Sharps Carbine

◾Smith

Carbine

◾Spencer Carbine

Widely Used to Limited Production Rifles and Carbines

|

|

|

|

|

The Civil War carbine was a long arm but with a shorter barrel than

a rifle or musket. Many carbines were shortened versions of full length rifles, using the same ammunition, as opposed

to stand alone designs with generally lower powered cartridges. Because of its smaller size and lighter weight, the carbine

was easier to handle and therefore issued to Civil War cavalry and mounted units. Rifle muskets were not the only weapons

in short supply during the Civil War, so the government, as well as individuals, sought weapons where it could -- including

contracts. One characteristic of these purchased weapons is their inventiveness. In the midst of conflict the government did

not have the time to experiment with new weapons, essentially continuing the manufacture of rifle muskets that were the creation

of more peaceful times. Private companies on the other hand, sought to expand their markets by improving their product. The

result was a variety of small arms, particularly in carbines.

| Civil War guns |

|

| Model 1859 Sharps Carbine |

(Right) Model 1859 Sharps Carbine, .54 caliber. With its shorter barrel

length of 22," this

easier to handle carbine was issued to Union cavalry during the Civil War. The carbine is rifled and uses a percussion cap,

but unlike most firearms of the era it was a breechloader. A paper cartridge was inserted into the breach and when it

was closed, it cut the back of the paper thus exposing the powder to the cap. Many Sharps rifles and carbines were converted

to the metallic cartridge after the war.

Although more than fifty different types of carbines were manufactured during

the Civil War, the carbine was produced for the cavalry. The Civil War carbine was also the testing ground for many

different inventions for breech-loading firearms.

The principal shoulder weapon of the mounted forces

was a short-barreled carbine. These were effective to 200 yards. Numerous designs appeared early in the war, and close to

20 different types were eventually adopted by the Union military. They ranged from fairly simple single-shot breech-loaders

using a paper or linen cartridge and a percussion cap, to complex repeaters firing self-priming metallic cartridges. Calibers

ranged from .44 to .54, and many carbines took specially made cartridges. Resupply of ammunition often proved tedious.

Two carbines rose to prominence by mid- Civil War. The Sharps

fired a paper combustible cartridge or could be loaded with a bullet and loose powder, while the Spencer fired a metallic

cartridge. Including both carbines and rifles, approximately 174,000 of both makes were manufactured during the conflict:

approximately 80,000 Sharps and more than 94,000 Spencers.

The Burnside was the third most manufactured carbine of the war, and the

Smith was the fourth most manufactured carbine of the conflict. The Henry was underpowered for military use--approximately

14,000 were made during the Civil War. The Henry, however, was modified after the war to become the first Winchester.

A few single shot carbines also fired the Henry .44 rimfire cartridge.

| Civil War carbine facts |

|

| Model 1860 Spencer Carbine |

(Right) Model 1860 Spencer Carbine .56-56. This Model 1861 Spencer

.52 cal. was manufactured with 22-inch barrel, walnut stock, steel carbine buttplate and sling swivel,

brass blade front and folding ladder rear sights, and mounted with a smooth walnut forearm and straight grip stock with saddle

ring and bar on the left wrist. The .56-56 Spencer cartridge. The first number referred to the diameter of the case ahead

of the rim, while the second number referred to the diameter at the mouth; the actual bullet diameter (caliber) was .52

inches.

One mainstay of the cavalry on both sides was the Sharps. In production since

the early 1850s, this .52 caliber arm was already known to be strong and reliable, and about 80,000 were purchased by the

Federals. The Sharps was the primary weapon of General John Buford's division as it delayed the Confederate infantry advance

towards Gettysburg on 1 July, 1863. Even though a single-shot, its breech-loading mechanism allowed a trooper to discharge

5 shots per minute, compared to the standard 3 aimed shots per minute from a muzzle-loading musket.

Although the Confederacy was not well positioned to manufacture its own firearms

during the Civil War, the Richmond Armory, in Virginia, during 1861-65, however, produced approximately 31,000 Model 1862

Richmond rifle muskets (also known as the Richmond Springfield, Confederate Springfield, and Richmond rifle), 1,350 short

rifles, and 5,400 carbines. The Richmond musket was also the most widely manufactured musket for the Rebel ranks. Designed

to fire the .58-caliber Minie ball projectile, the rifle had an effective range to 600 yards, and skilled soldiers could maintain

a rate of fire of three rounds per minute. While this musket was a sturdy, accurate and effective battle weapon that served

well, the carbine model was not.

| Civil War guns, carbines, and weapons |

|

| Confederate Model 1862 Richmond Carbine |

(Right) Confederate Model 1862 Richmond Carbine .58 caliber.

The Richmond Rifle had a 40 inch barrel with an overall length of 56 inches, but in November 1862 the Richmond Armory

began production of a cavalry carbine by reducing barrel length to 25 inches. While the carbine had an overall

length of 41 inches, both guns fired the coveted .58 caliber. The Southern cavalry fought mainly with single shot muzzle-loading carbines.

The Robinson factory in Richmond manufactured approximately 5,400 breech-loading carbines similar to the Sharps. The

South cut down infantry muskets or salvaged musket parts to make carbines. A more traditional muzzle-loading carbine

was made in the South by Cook and Brothers of Columbus, Georgia. The Southern cavalry also used single and even double

barrel shotguns. With a clean barrel, a good fit of a patched bullet in a smoothbore was accurate to at least 100 yards.

As

with the Springfield, the Confederates made their own copies of the Sharps, but demand far outstripped production. Regarding

the more than 5,000 Confederate or "Richmond" Sharps, General Robert E. Lee wrote that they were "so defective as to

be demoralizing to our men." Southern horsemen, however, were known to employ captured Yankee breech-loaders, for which

ammunition might be hard to come by, or stick with awkward short-barreled muzzle-loaders, for whom cartridges could be produced

locally. A few Southern arsenals, most notably the Richmond Arsenal in Virginia, the Fayetteville Arsenal in North Carolina

and the Cook & Brother Armory of Athens, Georgia, attempted to manufacture muzzle-loading carbines for Confederate troopers.

Production was slow and erratic, and never met the needs of the men in the field.

If the shortage of good, serviceable single-shot breech-loading carbines

did not vex the Confederate cavalryman, the appearance of reliable repeaters in the hands of his foes must surely have.

One such weapon was the Spencer, patented in 1860. Available

in .52 caliber, it was capable of sending out seven aimed shots within thirty seconds. The effects of such firepower were

overwhelming to Confederates used to the slower muzzle-loaders. Often, Federals with Spencers fired only one shot together

to simulate a volley of musketry and waited for the Confederates to advance. When they did, the Unionists unleashed the other

six shots in a rapid fusillade of fire that devastated the Southern lines. One Confederate observed, "There's no use fighting

against such guns..." More than 94,000 carbines were acquired for use by Federal forces. None of them were used

at Gettysburg, but the 5th and 7th Michigan regiments of General Custer's brigade were armed with the longer rifle version,

and did good service with them there. One Michigan trooper, Robert Trouax, later distinguished himself with his Spencer rifle

at the Rapidan River, "killing six rebels as they were crossing the river".

| Civil War weapons, carbines, and guns |

|

| 5th Model 1864 Burnside Carbine |

(Right) 5th Model 1864 Burnside Carbine .54 caliber. Manufactured 1863-1865,

the Burnside Carbine was one of the most widely issued and successful Federal cavalry carbines. This Fifth Model carbine

has the distinctive guide screw in the right side of the receiver. The top of the receiver is marked "Burnside Patent/Model

of 1864." This original Burnside has Pinched blade front sight and two leaf rear sight with graduations for 100, 300

and 500 yards. A cavalry sling bar and ring are mounted on the left side of the receiver. The barrel has a dull military blue

finish, the breech block, lever and receiver tangs are niter blue and the receiver, hammer, barrel band, lock plate and buttplate

are casehardened. Mounted with a smooth walnut forearm and straight grip stock with two clear boxed cartouches on the left

wrist.

Another repeater held in high esteem was the .44 caliber Henry Rifle. Carrying

16 shots, it too put a Confederate opponent at a severe disadvantage. While only 10,000 Henry Rifles were made, and only 1,731

purchased by the government, their presence on the battlefield was felt by the Confederates. One of General William T. Sherman's

soldiers stated: "I think the Johnnys are getting rattled; they are afraid of our repeating rifles. They say we are not fair,

that we have guns that we load up on Sunday and shoot all the rest of the week."

The ill-supplied Southern trooper could not hope to match the

firepower of these repeating weapons, for they utilized special copper rim-fire cartridges that were beyond the production

capability of Confederate ordnance. In the case of handguns, though, both sides were more evenly matched. The manufacturing

centers for these weapons were still located in the North, but few designs required the use of special ammunition. Captured

revolvers were much more easily (and hence much more often) turned against their former owners.

The many varieties of Civil War carbines has attracted collectors for many

years--at least since the 1920s. The Confederacy used far more captured carbines than it produced. This list summarizes

the carbines used or made during the Civil War.

| Name |

Manufactured |

North or South |

Loaded |

Caliber |

Quantity |

| Ballard |

Worcester, MA |

North |

Breech |

44 & 52 Rimfire |

8,400 |

| Burnside |

Providence, RI |

North |

Breech |

54 Percussion |

54,000+ |

| C Chapman |

Nashville, TN |

South |

Muzzle |

54 Percussion |

Less then 100 |

| Colt |

Hartford, CT |

PW/N |

Revolver |

36,44,56 Revolver |

4,435 |

| Columbus |

Columbus, GA |

South |

Muzzle |

58 Percussion |

183 |

| Cook & Brother |

New Orleans, LA; Athens, GA |

South |

Muzzle |

58 Percussion |

1,000 |

| Cosmopolitan |

Hamilton, Ohio |

North |

Breech |

52 Percussion |

1,140 |

| Davis &Bozeman |

Elmore, AL |

South |

Muzzle |

58 Percussion |

90 |

| Dickson, Nelson |

Adairsville, Macon, & Dawson, GA |

South |

Muzzle |

58 Percussion |

3,600 total for all carbines & rifles |

| Gallagher |

Philadelphia, PA |

North |

Breech |

50 Percussion |

18,000 |

| Gallagher |

Philadelphia, PA |

North |

Breech |

56-52 Rimfire |

5,000 |

| Gibbs |

New York City |

North |

Breech |

52 Percussion |

1,052 |

| Greene |

Chicopee Falls, MA |

North |

Breech |

54 Percussion |

300 |

| Gwen&Campbell |

Hamilton, Ohio |

North |

Breech |

52 Percussion |

8,200 |

| British, French, German, Austrian, and Other

Foreign |

Imported - North Bought to keep from the South |

N/A |

Muzzle |

50 through 75 |

|

| Hodgkins also Bilharz, Hall |

Macon, GA, Pittsylvania, VA |

South |

Breech |

58 Percussion |

400 to 700 |

| Jenks |

Pre-War 1839-60 |

PreWar |

Breech |

54 to 64 |

7,900 all models |

| Joslyn 1862 |

Milbury, MA |

North |

Breech |

52 Percussion |

3,500 |

| Joslyn 1864 |

Milbury, MA |

North |

Breech |

52 Rimfire |

13,000 |

| LeMat |

France |

South |

Revolver |

42 Rev& 63 Cntr |

2,500 |

| H.C. Lamb |

Jamestown, NC |

South |

Breech |

50 & 58 Perc |

532 |

| Lee |

Milwaukee, WI |

North |

Breech |

44 Henry Rimfire |

255 |

| Lindner |

Manchester, NH |

North |

Breech |

58 Percussion |

6,500 |

| Maynard |

Chicopee Falls, MA |

North |

Breech |

35 & 50 Perc. |

25,000 |

| Maynard or Perry by Keen, Walker |

Danville, VA |

South |

Breech |

54 Percussion |

280 |

| Merrill |

Baltimore, MD |

North |

Breech |

54 Percussion |

14,495 |

| Merrill, Latrobe |

Illion, NY c 1855 |

PreWar |

Breech |

58 Percussion |

170 |

| Mont Storm |

British via NY |

North |

Breech |

58 Percussion |

2,500 |

| Morse |

Greenville, SC |

South |

Breech |

50 Hybrid |

1,000 |

| J P Murray |

Columbus, GA |

South |

Muzzle |

58 Percussion |

Est 1000 |

| Palmer |

Windsor, VT |

North |

Breech |

50 Rimfire |

1,001 |

| Peabody |

Providence, RI |

North |

Breech |

50 Rimfire |

Few |

| Perry |

Newark, NJ 1857 |

North |

Breech |

54 Percussion |

275 |

| Remington |

Ilion, NY |

North |

Breech |

46 & 50 Rimfire |

2,500 |

| Richmond |

Richmond, VA |

South |

Muzzle |

58 Percussion |

5,400 carbines

(31,000 rifles)

(1,350 short rifles) |

| Robinson/CSA Duplicate Sharps |

Richmond, VA |

South |

Breech |

52 Percussion |

5,000 |

| Schroeder |

Bloomington, IL |

PreWar |

Breech |

53 Needle Fire |

10 in year 1857 |

| Sharps |

Hartford, CT |

PW / N |

Breech |

54 Percussion |

80,000 |

| Smith |

Springfield, MA |

North |

Breech |

50 Percussion |

30,000+ |

| Spencer |

MA & RI |

North |

Breech |

56-56 Rimfire |

95,000+ |

| Starr |

Yonkers, NY |

North |

Breech |

54 Percussion |

20,601 |

| Starr |

Yonkers, NY |

North |

Breech |

52 Rimfire |

5,002 |

| Symmes |

Worchester, MA |

PreWar |

Breech |

54 Percussion |

20 in year 1857 |

| Tallassee |

Tallassee, AL |

South |

Muzzle |

58 Percussion |

500 |

| Tarpley |

Greensboro, NC |

South |

Breech |

52 Percussion |

200+ |

| Triplett & Scott |

Meriden, CT |

North |

Breech |

50 Rimfire |

5,000 |

| US 1833, 36, 40, 42, 43 Hall |

Harpers Ferry, VA, & Middletown, CT |

PreWar |

Breech |

52, 58, 64 Percussion |

31,666 |

| US 1847 Musketoon |

Springfield, MA |

PreWar |

Muzzle |

69 Percussion |

9,300 |

| US 1855 Carbine |

Springfield, MA |

PreWar |

Muzzle |

54 Percussion |

1,020 |

| US 1855 Pistol - Carbine |

Springfield, MA |

PreWar |

Muzzle |

58 Percussion |

4,021 |

| Warner |

Springfield, MA |

North |

Breech |

50 & 56-50 RF |

4,000 |

| Wesson |

Worcester, MA |

North |

Breech |

44 Henry Rimfire |

5,600 |

| Civil War bullets and projectiles |

|

| Comparison of Centerfire and Rimfire Ignition |

Breechloaders A breech-loading weapon was a firearm in which the cartridge or shell was inserted

or loaded into a chamber integral to the rear portion of a barrel. During the Civil War, many breechloaders would be

fielded, including General Burnside's patented breech-loading carbine. Early firearms were almost entirely muzzle-loading.

The main advantage of breech-loading was a reduction in reloading time—it was much quicker to load the projectile and

charge into the breech than to force them down a long tube, especially when the tube had spiral ridges from rifling. In today's field

artillery, breech-loading allows the crew to reload the weapon without exposing themselves to enemy fire or repositioning

the piece (as was required for muzzle-loaded weapons) and allows turrets and emplacements to be smaller (since breech-loaded

weapons do not need to be retracted for loading). The improvements and advantages in breech-loaders led to the eventual retirement

of the muzzle-loaders. To utilize the enormous post war surplus of muzzle-loaders, the Allin conversion Springfield was

adopted in 1866. Many Civil War era breech-loader carbines employed the rimfire type cartridge. It is called a rimfire because

instead of the firing pin of a gun striking the primer cap at the center of the base of the cartridge to ignite it (as in

a centerfire cartridge), the pin strikes the base's rim. The rim of the rimfire cartridge is essentially an extended and widened

percussion cap which contains the priming compound, while the cartridge case itself contains the propellant powder and the

projectile (bullet). Once the rim of the cartridge has been struck and the bullet discharged, the cartridge cannot be reloaded,

because the head has been deformed by the firing pin impact. While many other different cartridge priming methods have been

tried since the 19th century, only rimfire technology and centerfire technology survive today in significant use.

| Union and Confederate Guns and Carbines |

|

| Model 1865 Spencer Carbine |

| Civil War guns, firearms, and small arms |

|

| Civil War Carbines |

(Above) Civil War carbines. From left to right, the breech-loading carbines: 1) Smith .54 caliber percussion. 2) Triplett

& Scott .50 rimfire repeater. 3) Maynard .54 cal. percussion. 4) Joslyn .50 rimfire. 5) Starr .54 cal. percussion.

6) Merrill .54 cal. percussion. 7) Sharps & Hankins .50 rimfire. 8) Burnside .54 cal. percussion. 9) Gwyn & Campell

.54 cal. percussion. 10) Gallager .54 cal. percussion. 11) Peabody .50 rimfire. 12) Westley Richards .450 percussion (British). The

US Model 1833 Hall carbine made by S. North in Middletown, Connecticut, was the first breech-loading rifle to be used in the

United States mounted service. It was a smoothbore weapon and was a .58-caliber. The barrel is 26.125 inches in length, and

all metal parts were browned with a lacquer finish for protection. Made specifically to arm the Regiment of Dragoons authorized

in 1833, it was fitted with a sliding bayonet.

In 1836 Hall, at Harpers Ferry, acquired a somewhat heavier carbine that consisted of rifle components. Also a percussion

arm, it had the rifle’s offset sights that have misled many into considering the arm a conversion from an original flint

lock carbine. Barrel length is 23 inches long, with a rod-bayonet.

| Civil War rifles and firearms |

|

| Civil War carbines, rifles, and breechloaders |

|

Comparative table and characteristics of most common Civil

War breechloaders |

| Feature / model |

Sharps rifle |

Sharps carbine |

Spencer rifle |

Spencer carbine |

Henry rifle |

| Weight |

9.5 lb |

7.75 lb |

10 lb |

8.25 lb |

9.25 lb |

| Length |

47.inches |

39.inches |

47.inches |

39 inches |

43.5 inches |

| Breech.type |

falling block |

falling block |

rolling block |

rolling block |

collapsing toggle |

| Cocking |

hammer, hand |

hammer, hand |

hammer, hand |

hammer, hand |

self-cocking |

| Caliber barrel |

.52 |

.52 |

.52 |

.52 |

.44* |

| Ignition |

percussion cap |

percussion cap |

rimfire |

rimfire |

rimfire |

| Cartridge type |

linen |

linen |

metal |

metal |

metal |

| Bullet diameter |

.535 inches |

.535 inches |

.535 inches |

.535 inches. |

.455 inches |

| Bullet volume |

370 grains |

370 grains |

285 grains |

285 grains |

216 grains |

| Powder charge |

80 grains |

80 grains |

48 grains |

48 grains |

25 grains |

| Magazine |

none |

none |

butt,7 rounds |

butt,7 rounds |

under barrel, 15 |

| Rate of fire |

10 rounds/min. |

10 rounds/min. |

30 rounds/min. |

30 rounds/min. |

40 rounds/min. |

| Range** |

200/1000 yd. |

200/1000 yd. |

200/500 yd. |

200/500 yd. |

200/400 yd. |

| Intro. year |

1848 |

1848 |

1863 |

1864 |

1862 |

* Cartridge is equivalent to today's .44 caliber special which has more

powder and a heavier bullet. The force of the bullet upon arrival, measured in foot-pounds, is almost identical, however.

**

Effective range is difficult to establish since it depended upon the skill and training of the marksman. In general the longer

barrels of the "rifles" made sighting easier, thus improving accuracy. Only with the "trained eye" could soldiers strike

a target beyond 200 yards.

Beginning in 1840, Simeon North delivered Model 1840 carbines, which were characterized by an

improved opening device (either an elbow lever or fishtail lever), and a 21-inch barrel with a conventional rod, which was

used for cleaning the bore. In 1843 North acquired the most common of the Hall models, the Model 1843 side-lever carbine--still

with the 21-inch barrel and rod.

To complete the tally, there was the Model 1842 carbine made at Harpers Ferry which was recognizable by its brass

fittings; butt plate, trigger guard, and barrel bands. It had a fishtail opening lever similar to North’s Model 1840

fishtail-lever arm. All carbines were delivered to the government as smoothbore weapons; later, during the Civil War, many

carbines of all models were rifled.

The standard weapon used by both sides during the Civil War, however, remained

the muzzle-loading .58 caliber rifle musket: the Union preferred the Springfield while the South the Enfield. It was an overall

fair weapon but its loading method limited its efficiency and at times made it dangerous. In the thick of the fray, soldiers,

forgetting they had previously loaded the weapon, were known to ram as many 4 or 5 loads into the muzzle, only failing

to discharge the piece. At other times the gun would misfire, and, thinking that the weapon had fired, the soldiers would

proceed to load it again. As a result, it was fairly easy to get more that one load into the weapon. After the battle of Gettysburg,

of the 27, 574 weapons picked up from the battlefield, approximately 6,000 were found to be properly loaded, and 12,000 had

three to ten loads. One rifle contained twenty-three loads. From these figures it was estimated that one-third of the fighting

men on each side during the battle were merely handling non-functioning weapons.

During the Civil War many private gun makers were experimenting with

breech-loading rifles. Some continued to use paper cartridges; others used metallic. The secret was to build a breech mechanism

that could withstand and contain the explosion of the gun powder. For the safety of the soldier, and to get the most efficiency

out of the cartridge, the breech had to be sealed tightly to prevent the escape of gases, yet the weapon had to be capable

of being reloaded quickly and not jamming. After the War, Springfield undertook production of some of these weapons in addition

to their Trapdoor models.

| Civil War Weapons - The Edged Weapons |

|

| Civil War era swords, Bowie knives, sabers, Arkansas toothpicks, and a host of other edged weapons. |

| Civil War edged weapons, knives, swords, & sabers |

|

| Two most widely used bayonets during the Civil War |

| Model 1840 |

|

| Cavalry saber |

Bayonets, sabers, swords, short swords, cutlasses, Bowie knives, pikes,

and lances, classified as "edged weapons," appeared in considerable profusion during the Civil War. While historians and writers

often relegate edged weapons as shiny decorative objects and elementary instruments of tradition during the conflict,

that was not the case. Although edged weapons were seldom wielded in battle and, compared to firearms, inflicted

few casualties, to the soldier the piece meant confidence on the battlefield,

and, while many of the sharp devices were designed as a last line of defense, to many of the cavalrymen at Gettysburg

in that sweltering Summer of 1863, it meant the difference between life and death. Viewing 1,000 troopers and their

unsheathed sabers advancing at a gallop upon their position, the adversary at times was in a state of

fear, panic, or even terror and was therefore unable to steady the musket or reload accordingly. At

close range the edged weapons were offensive devices capable of inflicting grave bodily harm, but at a distance they

were equally intimidating components of warfare.

Perhaps the most prominent account

of the employment of edged weapons during the conflict was during the battle of Gettysburg, when Colonel Joshua Chamberlain,

commanding 20th Maine Volunteers, was ordered by his brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Strong Vincent, to hold at all cost

the Union left flank, extreme left to be exact, on Little Round Top. Arriving by forced march, the 15th Alabama,

led by Colonel William Oates, made repeated assaults against the dogged Mainers only to be repulsed. Low on ammunition,

casualties mounting, and without reserves to reinforce his position, Chamberlain, now fearing his line would

either be rolled back or his position would simply be flanked by the relentless Confederates, ordered his men to

"Fixed bayonets!" During the fog of war, however, there was initial confusion from the Mainers. Chamberlain, nevertheless, advanced

and in piece meal his unrelenting men, with fixed bayonets, followed thus overrunning and even capturing 101

of the stunned Alabamians. Chamberlain was credited by both Union and Confederate generals alike, that if the 20th Maine had

collapsed or if Oates had flanked the unit, the determined Confederates would have poured onto the Great Top and forced

Meade to withdrawal his left wing, abandoning the high ground to Lee.

Oates later conceded that Col. Chamberlain's skill and

persistency and the great bravery of his men saved Little Round Top and the Army of the Potomac from defeat. Because if one more Confederate regiment had stormed the far left of the Army of the

Potomac with the 15th Alabama, "..we would have completely turned the flank and have won Little Round Top, which would

have forced Meade's whole left wing to retire." He concluded, philosophically, that "great events sometimes turn on comparatively

small affairs." Chamberlain, for his heroic and selfless actions on that contested top, would later receive the Medal of Honor

for "extraordinary heroism on 2 July 1863, while serving with 20th Maine Infantry, in action at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania,

for daring heroism and great tenacity in holding his position on the Little Round Top against repeated assaults, and carrying

the advance position on the Great Round Top."

Bayonets

Bayonets were detachable blades

put on the muzzle ends of muskets and rifles, for use in hand-to-hand fighting. The three steel and/or iron parts

of an angular bayonet (or socket bayonet) were the blade, socket and clasp. The blade had a sharp point and usually

three fluted sides The socket fit tightly over the outside of the muzzle and was secured to a stud on the barrel by the clasp.

Generally, the front sight of the gun was used as the bayonet-stud for angular bayonets. Bayonets were more of a psychological

weapon than a practical one. A company of infantry charging with polished bayonets created quite a site. However, the problem

with the bayonets is that if you were to stab someone with it, the gristle of the person you had stabbed would close

in around the bayonet, making it difficult to remove. The Civil War bayonet also enjoyed a more sedentary role as it

often substituted for tent pegs, pot hooks, candlesticks, skewers, and entrenching tools.

| Types of Civil War weapons |

|

| Civil War soldier with D-guard Bowie knife |

(Left) U.S. Model 1840 Heavy

Cavalry Saber. The Model 1840 saber was manufactured by N.P. Ames in Springfield, Massachusetts, although many were made in

Prussia. Because this saber was readily available in U.S. stockpiles when

the Civil War began, it was issued to Union soldiers and, although it was replaced with the Model 1860, it was preferred

by some soldiers until the cessation of hostilities.

Knives

Not to be confused with the Bowie

knife, the Arkansas toothpick, synonymous with the South, was a heavy dagger with a 12–20-inch pointed,

straight blade. Dissimilar to the Bowie knife, the Arkansas toothpick was balanced and weighted for throwing, but it

was designed primarily for thrusting and slashing.

The Bowie knife, however, was a patterned fixed-blade fighting

knife popularized by famed Alamo defender Colonel James "Jim" Bowie (ca. 1796-1836) in the early 19th century. Although

Bowie designed the famous blade, James Black (1800-1872), an Arkansas blacksmith, created

the historical Bowie knife. The Bowie was not a single design, but was a

series of knives improved numerous times by Jim Bowie over the years.

(Right) Civil War soldier with D-guard Bowie knife.

Some Confederate soldiers and troopers carried the D-guard Bowie with blade lengths extending to 24-inches.

Qualifying as a short sword, the favored blade was discarded for more practical weapons as the conflict progressed.

The most famous version of the Bowie knife was designed by Jim Bowie and

presented to James Black in the form of a carved wooden model in December 1830. Black produced the knife ordered by Bowie,

and at the same time created another based on Bowie's original design but with a sharpened edge on the curved top edge of

the blade. Black offered Bowie his choice and Bowie chose the modified version. Resembling knives, however, with a blade shaped

closely to that of the Bowie knife, but with a pronounced false edge, are presently known as "Sheffield Bowie" knives, because

this blade shape became so popular that cutlery factories in Sheffield, England were mass-producing such knives for export

to the U.S. by 1850, usually with a handle made from either hardwood, deer antler, or bone, and sometimes with a guard and

other fittings of sterling silver. The James Black Bowie knife had a blade approximately twelve inches long, two inches wide,

and 0.25 inch thick. The spine of the knife was covered with soft brass or silver, reportedly to catch the opponent's blade

in the course of a knife fight, while a brass quillion protected the hand from the blade.

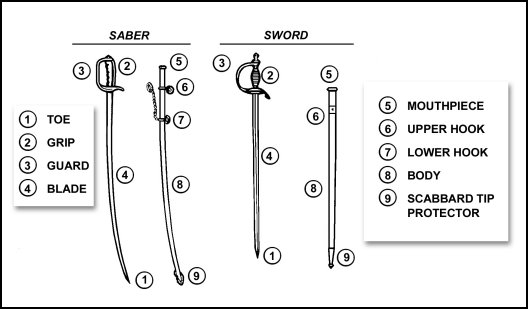

Sword and Saber

What is the difference between a sword and a saber?

The sabre or saber is a sword that usually has a curved, single-edged

blade and a rather large hand guard, covering the knuckles of the hand as well as the thumb and forefinger. Although sabers

are typically thought of as curved-bladed slashing weapons, those used by the world's heavy cavalry often had straight and

even double-edged blades more suitable for thrusting. The length of sabers varied, and most

were carried in a scabbard hanging from a shoulder belt known as a baldric or from a waist-mounted sword belt, usually with

slings of differing lengths to permit the scabbard to hang below the rider's waist level. A cutlass is a short, broad saber

or slashing sword, with a straight or slightly curved blade sharpened on the cutting edge, and a hilt often featuring a solid

cupped or basket-shaped guard. It was a common, preferred naval weapon because

of its size. It could be brandished easily, making it the preferred edged weapon for pirates, too, and it was more effective

as a close-combat weapon than a full-sized sword would be on a cramped ship.

| Civil War Edged Weapons |

|

| Names of the parts for the Saber, sword, and scabbard parts |

| Civil War Edged Weapons |

|

| Civil War swords, sabers, and edged weapons |

| Civil War guns and weapons |

|

| Civil War soldier with Arkansas Toothpick and rifle |

(Above) Variety of Civil War era sabers, swords, and scabbards

from the Union 1861 Ordnance Manual.

Sword and Saber Terminology

Hilt: Sum of the parts of the handle.

Pommel: Terminal knob of the hilt.

Cross Guard: The cross piece set at right angles

just below the hand grip to protect the thumb and fingers.

Quillons (ke-yon'): The two arms of the cross guard.

Knuckle-bows: Curved guards of various types (and

modes of attachment) designed to afford protection to the knuckles of the fingers and thumb.

Back-strap: A metal strip which extends the pommel

all the way to the rear quillon and forms the back of the grip.

Fuller: A channel or groove in the blade.

(Right) Civil War soldier with musket and attached bayonet,

and Arkansas toothpick.

Sabers

Saber blades were generally 36 inches or less in length and approximately

1 1/4 inches wide. For centuries the arm considered most essential to cavalry had been the saber. Oddly, the U.S. Army,

from its beginning, rarely saw fit to emphasize standardized training of its mounted men to make them sufficiently proficient

with the saber in battle. There were, however, saber exercises in the dragoon and mounted riflemen regiments, but the training

was not on a level with the training European cavalrymen experienced. In spite of the general disenchantment with the

saber as an effective cavalry weapon, all the mounted units of the U.S. Army, from the Continental Dragoons to the modern

cavalry, were armed with one type of saber or another, until that weapon was finally

discontinued as a cavalry weapon in 1934.

The

U.S. Model 1840 Cavalry Saber, aka 1840 heavy saber, had the nickname of "Old Wristbreaker" because it was fairly easy

for the soldier to break his wrist in combat if he utilized the saber incorrectly. The proper way to hold the saber

was inverted and away from your body. Sabers were intended to be a thrusting weapon not a slashing weapon, and it was used

exclusively from horseback in close combat. The saber knot would be used as a strap and wrapped around the wrist to prevent

the saber from being lost if it should be dropped in battle.

The American Pattern of 1860 Light Cavalry Saber was lighter than the typical European saber,

the latter being similar to the older Model 1840 "wrist breaker". The curved blade of the saber was generally sharpened

only at the tip because it was used mostly for breaking arms and collarbones of opposing horsemen, and sometimes stabbing,

rather than for slashing flesh.

| Civil War Artillery Saber |

|

| US Model 1840 Light Artillery Saber with scabbard |

Model 1840 Light Artillery Saber

The U.S. Model 1840 Light Artillery Saber was a saber of 42 inches

in length with a curved, single-edged blade and iron scabbard. The M1840 light saber has a brass hilt and knuckle-bow

of 6 inches in length, the grip wrapped in leather and bound with brass wire, and a blade of 36 inches in length. Differing

from the Model 1840 Cavalry Saber, the artillery model has no basket.

This model was one of the many weapons produced by the Ames Manufacturing

Company of Springfield (later Chicopee), Massachusetts. The mounted artillery units accompanied dragoons to provide them with

more firepower. The primary weapon of the mounted artillery were their cannons. Although this saber belonged to the artillerist's

list of accoutrements, it was rarely used in battle.

Model 1840 Heavy Cavalry Saber

The Model 1840 Cavalry Saber, also known as Model 1840 Heavy Saber to distinguish

it from the 1840 artillery saber, was based on the 1822 French hussar's sabre. The M1840 cavalry saber, recognizably

different than its replacement, Model 1860 Light Cavalry Saber, has a ridge around its quillon, a leather grip wrapped in

wire (rather than grooves cut into the wooden handle) and a flat, slotted throat. It is 44in long with a 35-inch blade and

weighs roughly 2.5 lbs.

| Civil War Cavalry Saber |

|

| US Model 1840 Heavy Cavalry Saber with scabbard |

Designed for slashing, the 1840 cavalry saber was given the nom