|

|

Battery Marsh and the Swamp Angel

Morris Island, Charleston, and Civil War

The Swamp Angel

| Swamp Angel |

|

| Swamp Angel in the marshes south of Charleston in 1863 |

Summary

On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces bombarded Fort Sumter and the Civil

War began. The Federal garrison surrendered the next day and evacuated on the 14th, leaving the fort in Confederate hands.

Throughout the Civil War Fort Sumter was the center of conflict as Union forces struggled to regain the fort and control of

Charleston Harbor.

Fort Sumter was subjected to a Union blockade, attacks by ironclad warships,

and a twenty-two month siege, one of the longest in U.S. Military History. Heavy shelling by Union land batteries (1863-65)

reduced most of the fort to a mound of rubble by the war's end.

In 1861 the port of Charleston, South Carolina, prospered. Keeping

the city open to trade was crucial for Confederate survival. Confederate forts in Charleston Harbor - including Fort Sumter

- protected Charleston throughout the war despite Union blockade, warship attack, and two years of bombardment

and siege.

(Right) The mammoth "Swamp Angel" weighed more than eight tons, but determined

Federals, while donned in Union issued wool uniforms, managed to maneuver the colossal gun beyond the island and stationed

it on a manmade platform in the snake and mosquito infested marsh during the blistering summer of 1863.

Morris Island, an 840 acre uninhabited island in Charleston

Harbor, was accessible only by boat, and the island was in the outer reaches of the harbor and thus a strategic location in

the Civil War.

Despite military conflict in the harbor, relative peace prevailed in the

city until 1863, when Union forces captured nearby Morris Island and began shelling Charleston. This was a deliberate bombardment

of civilians; the North hated Charleston for leading the secessionist movement and firing the first shots of the war. The

Union bombardment, along with a devastating fire in 1861 and other fires set by evacuating Southern forces in February 1865,

destroyed much of the lower city.

In 1863 Union forces built an artillery battery in the marsh on lower

Morris Island and in close proximity of Charleston. They successfully mounted an eight-inch Parrott rifle referred to as the

"Swamp Angel," which was a huge gun that fired 150-pound shells over a distance of five miles and into the city of Charleston.

The Swamp Angel's first shot at 1:30 a.m. on August 22 caused panic in Charleston.

This deliberate bombardment of a civilian population shattered the city's security. The Swamp Angel's brief career ended abruptly

the following day when the overcharged gun burst while firing its 36th round. Other guns soon took its place, and the bombardment

of Charleston continued intermittently for the next 18 months.

| The famous 200-pounder "Swamp Angel" |

|

| Morris Island (vicinity), South Carolina. The "Marsh Battery" or "Swamp Angel" after the explosion |

(Above) Morris Island, South Carolina. The "Marsh Battery," aka "Swamp Angel,"

after the explosion, August 22, 1863. The 8-inch 200-pounder Parrott rifle nicknamed the "Swamp Angel" was thrown forward

on the parapet after bursting. The gun became the most famous Parrott rifle when it burst after shelling Charleston 36 times.

(High Resolution) Courtesy Library of Congress.

Blockade Runners

The Union Navy blockaded Charleston Harbor from 1861-65, but blockade runners

continued to slip in and out, carrying cargo crucial to the economic and military survival of the South. Using neutral ports

like Bermuda and Nassau, blockade runners brought food, medicine, weapons, ammunition, and manufactured goods from Europe.

They left primarily with cotton, but also carried diplomats, dispatches, and various products and valuables.

The risk of capture or sinking by Union warships was great, but so were

the rewards. One voyage could bring a profit of $100,000. Despite the blockade, seventy-five percent of the runs were successful.

Morris Island

With a population of 40,522, Charleston was ranked the 22nd largest city

in the nation according to the 1860 U.S. census. Long feared as a target for foreign invasion, the Charleston Harbor was ringed

with a series of forts, bastions, and floating batteries to protect it from an enemy fleet.

Confederate batteries, initially hidden in the dunes of Morris Island, commanded

the approach to Charleston Harbor. Union forces needed Morris Island, a key location from which to attack Fort Sumter, less

than one mile away. On July 18, 1863, a direct assault failed against Fort Wagner,

a Confederate stronghold near Morris Island's north end. The Union then changed tactics, subjecting Fort Wagner to a two-month

siege. The Confederates finally evacuated, abandoning Morris Island on September 6,

1863. Union gunners then aimed powerful rifled cannon at Fort Sumter. In the next two years, massive bombardments reduced

most of Sumter to rubble. See also Civil War Charleston and Coastal Defenses.

| Fort Sumter in 1865 |

|

| Swamp Angel and Fort Sumter History |

(Above) Fort Sumter in 1865. A view of Fort Sumter located in Charleston

Harbor, S.C., from a sandbar in 1865, after years of Union artillery bombardment.

On the night of September 8, 1863, a Union tugboat towed 500 sailors and

marines in small boats to within 400 yards of Fort Sumter, then cast them loose to assault the fort. But the Confederates

expected the attack. As the leading boats landed, the defenders opened fire, hurling grenades and bricks down upon the assailants.

Guns of Fort Moultrie and the Confederate gunboat Chicora opened fire. The remaining boats retreated and 124 Union men were

killed, wounded, or captured. For the next sixteen months, Union forces continued to bombard Fort Sumter, but never attempted

another landing.

The Siege

The Union siege of Fort Sumter lasted from April 7, 1863 until its evacuation

by Confederate forces on Feb. 17, 1865 (roughly two month before Lee surrendered to Grant). Oddly, Fort Sumter was impervious

to both smoothbore and rifle fire. The smoothbore was considered obsolete against masonry fortifications, but with the

employment of the new rifled-gun, masonry forts were considered obsolete. As Fort Sumter was pulverized, however, with

thousands of tons of projectiles, it literally crumbled and bowed (as though it extended an invitation) to the Union siege

fire and became thicker and stronger. During the siege, Fort Sumter appeared to convert to a solid masonry (earthen)

work -- which rifles had no effect.

Quincy Adams Gillmore

During siege operations against Fort Pulaski, Georgia, in 1862, Brig. Gen.

Quincy Gillmore effectively deployed new rifled artillery against the masonry fort and clinched its surrender with

an unprecedented 30 hour bombardment. Smoothbore cannon was out, and the rifled gun was in. Although Pulaski

was designed to withstand smoothbore fire, its walls were breached within hours by the rifles. Gillmore, the first officer

to employ rifled guns and destroy an enemy stone fortification, had sealed his name in the annals of siege warfare,

but by mid-1863 his career had stymied.

From June 12, 1863, to May 1, 1864, Gillmore commanded the Department

of the South, consisting of North and South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, with headquarters at Hilton Head. The accomplished

general now focused on defeating the defenses surrounding Charleston, South Carolina. Initially successful in an attack on

the southern end of Morris Island on July 10, Gillmore believed that a decisive assault against Fort Wagner, on

the north end of the island, would subdue the entire island. The following

day he launched the initial attack on Fort Wagner only to be repulsed. He assembled a larger assault force and with the assistance

of John A. Dahlgren's naval fleet planned a second attack. On July 18, 1863, Gillmore's troops were again repulsed but with

heavy losses in the Second Battle of Fort Wagner. Gillmore's divisional commander, General Truman Seymour was wounded and

two brigade commanders, George Crockett Strong and Haldimand S. Putnam were killed in the attack. Unaccustomed to successive defeats,

Gillmore would soon deploy a new strategy against Charleston, the cradle of the rebellion.

Swamp Angel

| The Union Swamp Angel |

|

| Swamp Angel, Morris, Island, S.C., in Summer of 1863 |

The "Swamp Angel" was the nickname given to a 16,500 pound rifled Parrott

cannon with an eight-inch bore that briefly shelled the city of Charleston in August 1863. The massive gun was positioned

near Morris Island in an earthwork made of sandbags known as the Marsh Battery. The construction of the Marsh Battery, which

virtually floated on the marsh, was considered to be one of the greatest engineering feats of the war. The battery was completed

by mid-August 1863 and by August 21 the Swamp Angel was mounted and ready to fire incendiary shells 7,900 yards into Charleston.

Before the first shot was fired, the Union commander, Quincy A. Gillmore, demanded that the Confederates evacuate Morris Island

and Fort Sumter or he would fire on the city. The request was refused and early on the morning of August 22, using a compass

reading on St. Michael’s steeple, the first shell was fired into Charleston. The shelling continued until daylight

and then resumed on the evening of August 23 when the Swamp Angel exploded while firing its thirty-sixth round. The bombardment

of the city would continue from other batteries and new guns mounted in the Marsh Battery throughout the war.

One of the most famous Parrott rifles was the Swamp Angel, an 8-inch (200-pounder)

gun used by Union Brigadier General Quincy Adams Gillmore to bombard Charleston, South Carolina. Although it was manned by

the 11th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment, the gun injured 4 of its inexperienced crew when it burst during its short deployment.

The mission of the "Swamp Angel" was to deter shipping into Charleston, stated Brig

Gen. Gillmore. But on August 21, 1863, frustrated with his lack of progress,

Gillmore sent Confederate general P. G. T. Beauregard an ultimatum to abandon heavily

fortified positions at Morris Island or the city of Charleston would be shelled. When the positions were not evacuated

within a few hours, Gillmore ordered the Parrott rifle to "fire on Charleston to its west northwest."

(Right) Although the Marsh Battery

"Swamp Angel" weighed more than 8-tons, it was protected by 13,000 sandbags, and its massive weight was supported by 123

large timbers that were used as pilings by being sunk into the marsh.

While Charleston was the hotbed

of the rebellion, its marshes were the center for diseases, snakes, and mosquitoes. The men of Maine who

manned the Swamp Angel were not accustomed to Charleston's sweltering heat, menacing mosquitoes, and very high levels of pollen.

Without shelter, the men in the marsh were exposed to summer temperatures that

often embraced 100 degrees, while humidity was nearly 100%. According to the few photographs in circulation, the Mainers often

wore the standard Union wool uniform, clothes associated with Northern climate and Southern winters. Confederate

soldiers, on the other hand, often wore cotton or cotton-wool blend uniforms.

Bombardment

Between August 22 and August 23, when temperatures remained

above 95 degrees, the Swamp Angel fired indiscriminately and erratically on the city of Charleston 36 times

(the gun burst on the 36th round), using many incendiary shells which caused little damage and few casualties. The bombardment

was made famous by Northern newspapers and even Herman Melville's poem "The Swamp Angel". The fact that the Union gunners

fired the 200-pounder Parrott inaccurately and amiss was discarded by Gillmore as he later conceded that the weapon

had fired on Charleston merely to train his men with the new cannon and to learn valuable

artillery techniques. It was summarized as an experiment. Gillmore, however, had a vendetta against the Charlestonians,

because he had observed many Union men fall on numerous battlefields, including the heroic 54th Massachusetts as

it was decimated when it assaulted nearby Battery Wagner during the previous month of July. Charleston

was the cradle of the rebellion. Cognizant that Northerners wanted revenge, politicians wanted revenge, and the Union Army

wanted redemption and revenge, Gillmore was not going to disappoint his countrymen.

The gunners of the "Swamp Angel" were instructed that the Parrott was

not a new gun and that the exploding shells shortened its life. During the bombardment, the artillerists observed the Swamp

Angel's barrel moving in the breech-band, but ignored this textbook warning and continued to fire additional projectiles.

The breech of the Swamp Angel soon exploded, hurling the gun onto the parapet, while injuring four of its crew.

The 200-pounder Parrott was known for its accuracy,

but accuracy was only obtained with veteran artillerists of said gun.

In other words, the siege gun, like any gun, was only accurate when used by a well-trained crew. In inexperienced hands,

the cannon was also a threat to its crew, as was the case with the "Swamp Angel." The Parrott Class guns were well-known

for their muzzle bursting, but the Parrotts were inexpensive, mass produced guns and in the hands of seasoned gunners

they could accurately deliver large, devastating projectiles to any target. While the Swamp Angel was famous, it was not

the largest of the Parrotts. The largest was the 10-inch (300-pounder) Parrott rifle, but only three were in service. While

the 300-pounders were all employed on Morris Island, muzzle bursting also plagued the colossal guns. See also

Civil War Artillery and

Cannon: Field, Garrison and Siege, and Seacoast.

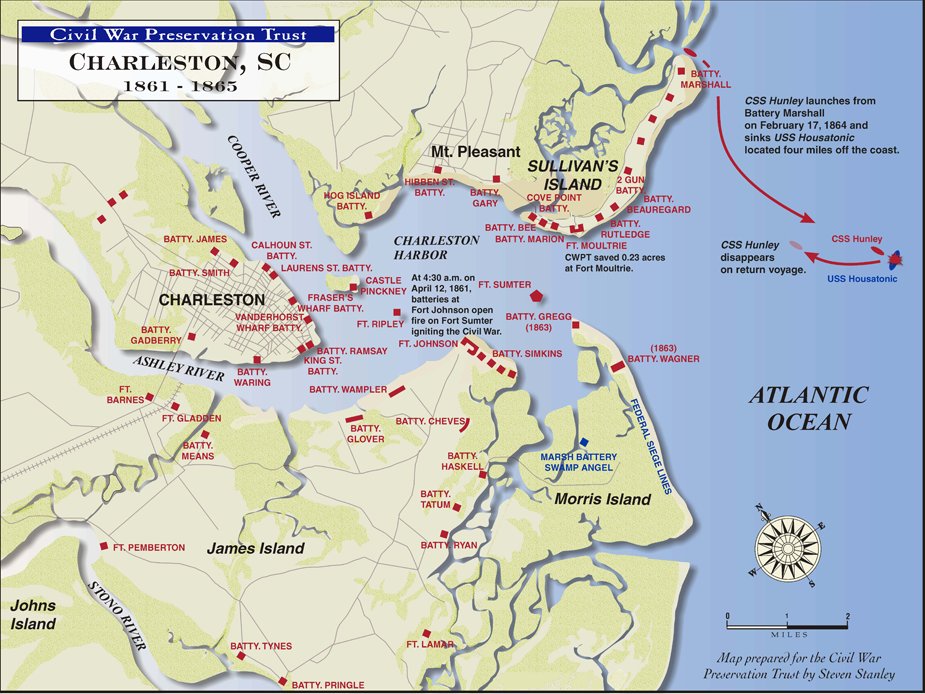

| Charleston during the Civil War |

|

| Map depicting the defenses of Charleston during the Civil War |

| Swamp Angel Historical Marker |

|

| Swamp Angel Interpretive Marker |

(Right) Inscription: The first gun an eight inch Parrott Rifle or 200 pounder,

fired from the Marsh Battery, on Morris Island, S.C. at the City of Charleston, 7,000 yards distance. Weight of gun 16,500

pounds, weight of charge of powder 16 pounds, and weight of projectile 150 pounds, greatest elevation used 35 degrees. Bombardment opened August 12, 1863 – gun burst at 36th round. Erected February 1871 at corner of No. Clinton Avenue and Perry Street, Trenton. Rededicated

at Cadwalader Park on 100th anniversary of start of American Civil War April 12, 1961.

Conclusion

Historians have argued that Charleston was a legitimate target since it

was producing munitions, but that argument could be made for the majority of Southern and even Northern cities. While

Charleston had legitimate military targets, Gillmore stated precisely why and where he would attack. He stated that he would

retrain his guns from attacking Confederate batteries, obvious military targets, and train them on the "city of Charleston."

Gillmore never stated in his two ultimatum letters to Confederate Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, commanding forces in Charleston, that

he was going to attack war making facilities in Charleston. The Union general unabashedly stated that his gunners would

open fire on Charleston, a city filled with civilians, including babies, children, women, elderly, and disabled. The

argument that he fired on military targets in Charleston, was blatantly false, because Gillmore's second letter reiterated that

his target was the "city of Charleston," and when the "Swamp Angel" fired erratically on residential neighborhoods in

the city, it corroborated both letters stating that Charleston was indeed the target to be shelled.

Gillmore's utter disregard for civilians did not go unnoticed, however.

Foreign politicians and dignitaries condemned the "barbaric action," while many Southerners -- women, children and the

elderly -- were, nevertheless, terrorized by the sheer sound of the behemoth shooting indiscriminately across the city.

| Civil War and the Swamp Angel |

|

| Swamp Angel in ruins |

(Above) "Swamp Angel in Ruins." To support the Swamp Angel in the marshes

of Morris Island, Ripley cites engineering records stating 13,000 sandbags were used along with 123 pieces of 15- to 18-inch

timbers for the pilings sunk into the marsh and 9,156 feet of 3-inch planking.

In his official correspondence,

Beauregard stated to Gillmore that he was appalled at the fact that he fired on Charleston and not on targets, and

that his actions would be met with a harsh response from the Confederate batteries. Although fame and infamy was bestowed

upon the "Swamp Angel," it was soon surpassed with Northern and Southern headlines alike detailing Sherman's

March to the Sea.

After the war, a damaged Parrott rifle, believed to be the "Swamp Angel,"

was moved to Trenton, New Jersey, where it currently rests as a memorial at Cadwallader Park. While the rifle retained its nom

de guerre of "Swamp Angel" by Northerners, it was known as that "Swamp Devil" by Southerners.

See also

Sources: Library of Congress, National

Archives, National Park Service, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Civil War Trust online civilwartrust.org;

Johnson, John. The Defense of Charleston Harbor. Charleston, S.C.: Walker,

Evans & Cogswell, 1890; Olmstead, Edwin, Wayne E Strak, and Spencer

C. Tucker. The Big Guns. Alexandria Bay, N.Y.: Museum Restoration Service, 1997; Ripley,

Warren. Artillery and Ammunition of the Civil War. Charleston, S.C.: The Battery Press, 1984; Wise, Stephen R. Gate of Hell: Campaign for Charleston Harbor, 1863. Columbia,

S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1994.

|

|

|