|

|

The Republican Threat

For all the popular hysteria they were instrumental in whipping up, the

secessionists quite rationally assessed the nature of the Republican threat. The Republican stand against the expansion of

slavery struck at the vital interests of the slave South. Economically, it threatened to choke off the profits of plantation

agriculture by denying it access to fresh, arable lands. As a consequence, Southerners told themselves, whites would flee

the slave states, and to save themselves, the dwindling numbers of whites would have to wage a preemptive war of extermination

against the growing black majority. Politically, as free states were carved out of the territories, Southern power in Congress

would he reduced to the point where slavery in the states could he dismantled by the ever larger political majority in the

North. Most degrading of all from the Southern perspective was the humiliation implicit in submitting to the rule of an antislavery

party. To do so would be an admission to Northerners and the outside world that the Southern way of life was morally suspect.

Only slaves, the secessionists insisted, acted in such a servile fashion.

The secessionists did not expect the Republicans to make an immediate

and direct move against slavery They were well aware that the Republicans did not control Congress or the Supreme Court. As

a new and still untested party, the Republicans would have to cooperate with Southern and Democratic politicians. But, reasoned

the secessionists, such a demonstration that the slave South could, in the short run, survive under a Republican administration,

would establish the fatal precedent of submitting to Republican rule and blunt the spirit of Southern resistance. In the meantime,

the Republicans could use what power they had to begin the slow dismantling of slavery. The whole purpose of the Republican

determination to prohibit the expansion of slavery was to put it on the road to extinction in the states where it existed.

In addition to all the perceived horrors of encirclement by a swelling

majority of free states, the secessionists warned of changes in the sectional balance that the Republicans could potentially

implement. They could move against slavery in Washington, D.C., and in Federal forts and installations. They could force the

introduction of antislavery literature into the South by banning censorship of the Federal mails and simultaneously position

the Supreme Court to overturn the Dred Scott ruling. They could weaken or repeal the Fugitive Slave Act and prohibit the interstate

slave trade, a key link in the profitability of slavery to the South as a whole. Most alarming of all from the standpoint

of the secessionists was the possibility that the Republicans would use Federal patronage and appointments to build a free

labor party in the South. Senator Robert Toombs of Georgia echoed the concerns of many secessionists when he predicted in

1860 that Republican control of Federal jobs would create an "abolition party" within a year in Maryland, within two years

in Kentucky, Missouri, and Virginia, and throughout the South by the end of four years.

Southern Divisions Over Slavery

The Toombs prediction went to the heart of secessionists fears over the

commitment to slavery within the South. To be sure, very few Southern whites by 1860 favored an immediate end to slavery.

Most such whites had left the South in the preceding generation, either voluntarily or in response to community pressures

forcing them out. Nonetheless, deep divisions existed over the future of slavery and the direction of Southern society itself.

The Jeffersonian dream of a gradual withering away of slavery persisted

in the upper South. Many whites could contemplate and even accept the eventual end of the institution as long as there was

no outside interference in the process of disentanglement. In this region, as the proportion of slaves in the total population

steadily declined in the late antebellum decades, slavery was increasingly becoming a matter of expediency, not of necessity.

The secessionists had every reason to believe that a Republican administration would encourage the emancipationist sentiment

that had already emerged among the white working classes in such slave cities as St. Louis, Baltimore, and Richmond.

In the lower South the secessionists doubted the loyalty to slavery

of the yeomanry, a class of nonslaveholding farmers who composed the largest single bloc in the electorate. Although tied

to the planters by a mutual commitment to white supremacy and often by bonds of kinship, these farmers occupied an ambivalent

position in Southern society. They fervently valued their economic independence and political liberties, and hence they resented

the spread of the plantation economy and the planters pretensions to speak for them. But as long as the yeomen were able to

practice their subsistence-oriented agriculture and the more ambitious ones saw a reasonable chance of someday buying a few

slaves, this resentment fell far short of class conflict. In the 1850s, however, both these safety valves were being closed

off The proportion of families owning slaves fell from 31 to 23 percent. Sharply rising slave prices prevented more and more

whites from purchasing slaves. At the same rime, railroads spread the reach of a plantation agriculture geared to market production.

Rates of farm tenancy rose in the older black belts, and the yeomen's traditional way of life was under increasing pressure.

Distrustful of the upper South as a region and the yeomanry as a class,

the secessionists pushed for immediate as well as separate state secession. By moving quickly, they hoped to prevent divisions

within the South from coalescing into a paralyzing debate over the best means of resisting Republican rule. Since most of

the rabid secessionists were Breckinridge Democrats, the party that controlled nearly all the governorships and state legislatures

in the lower South, the secessionists were able to set their own timetable for disunion.

| Why did the South secede? |

|

| Wny did the Southern states secede? |

The Southern States Secede

South Carolina was in the perfect position to launch secession. Its governor,

William H. Gist, was on record as favoring a special state convention in the event of a Republican victory, and the legislature,

the only one in the Union that still cast its states electoral votes, was in session when news of Lincolns election first

reached the state. Aware of South Carolinas reputation for rash, precipitate action and leery of the states being isolated,

Gist would have preferred that another state take the lead in secession. But having been rebuffed a month earlier in his attempt

to convince other Southern governors to seize the initiative, he was now prepared to take the first overt step. The South

Carolina legislature almost immediately approved a bill setting January 8 as the election day for a state convention to meet

on January 15.

Secession might well have been stillborn had the original convention

dates set by the South Carolina legislature held. A two-month delay, especially in the likely event that no Southern state

other than South Carolina would dare to go out alone, would have allowed time for passions to subside and lines of communication

to be opened with the incoming Republican administration. But on November 10 a momentous shift occurred in the timing of South

Carolinas convention. Reports of large secession meetings in Jackson, Mississippi, and Montgomery, Alabama, and reports that

Georgia's governor, Joseph E. Brown, had recommended the calling of a convention in his state emboldened the South Carolina

secessionists to accelerate their own timetable. They successfully pressured the South Carolina legislature to move up the

dates of the states convention to December 6 for choosing delegates and December 17 for the meeting.

The Lower South Secedes

The speedy call for an early South Carolina convention triggered similar

steps toward secession by governors and legislatures throughout the lower South. On November 14 Governors Andrew B. Moore

of Alabama and J. J. Pettus of Mississippi issued calls for state conventions, both of which were to be elected on December

24 and meet on January 7. Moore had prior legislative approval for calling a convention, and Pettus was given his mandate

on November 26. Once the Georgia legislature voted its approval on November 18, Governor Brown set January 2 for the election

of Georgia's convention and January 16 for its convening. The Florida legislature in late November and the Louisiana legislature

in early December likewise authorized their governors to set in motion the electoral machinery for January meetings of their

conventions. Texas was a temporary exception to the united front developing in the lower South for secession. Its governor,

Sam Houston, was a staunch Unionist who refused to call his legislature into special session. As a result, Texas secessionists

resorted to the irregular, if not illegal, expedient of issuing their own call for a January convention.

Within three weeks of Lincoln's election the secessionists had generated

a strong momentum for the breakup of the Union by moving quickly and decisively. In contrast, Congress, acting slowly and

hesitantly, did nothing to derail the snowballing movement. Congress convened

on December 3, and the House appointed a Committee of Thirty-three (one representative from each state) to consider compromise

measures. The committee, however, waited a week before calling its first meeting, and the creation of a similar committee

in the Senate was temporarily blocked by bitter debates between Republicans and Southerners. When the House committee did

meet on December 14, its Republican members failed (by a vote of eight to eight) to endorse a resolution calling for additional

guarantees of Southern rights. Choosing to interpret this Republican stand as proof that Congress could accomplish nothing,

thirty congressmen from the lower South then issued an address to their constituents declaring their support for an independent

Southern confederacy A week later, on December 20, South Carolina became the first state to leave the Union when its convention

unanimously approved an ordinance of secession.

South Carolina provided the impetus, but the ultimate fate of secession

in the lower South rested on the outcome of the convention elections held in late December and early January in the six other

cotton states. The opponents of immediate secession in these states were generally known as cooperationists. Arguing that

in unity there was strength, the cooperationists wanted to delay secession until a given number of states had agreed to go

our as a bloc. Many of the cooperationists were merely cautious secessionists in need of greater assurances before taking

their states out. But an indeterminate number of others clung to the hope that the Union could still be saved if the South

as a whole forced concessions from the Republicans and created a reconstructed Union embodying safeguards for slavery.

Any delay, however, was anathema to the immediate secessionists. They

countered the cooperationists fears of war by asserting that the North would accept secession rather than risk cutting off

its supply of Southern cotton. The secessionists also neutralized the cooperationist call for unanimity of action by appointing

secession commissioners to each of the states considering secession. The commissioners acted as the ambassadors of secession

by establishing links of communication between the individual states and stressing the need for a speedy withdrawal. In a

brilliant tactical move, the South Carolina convention authorized its commissioners on December 31 to issue a call for a Southern

convention to launch a provisional government for the Confederate States of America. Even before another state had joined

South Carolina in seceding, the call went out on January 3 for a convention to meet in Montgomery, Alabama, on February 4,

1861.

The secessionists won the convention elections in the lower South, but

their margins of victory were far narrower than in South Carolina. The cooperationists polled about 40 percent of the overall

vote, and in Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana they ran in a virtual dead heat with the straight-out secessionists. Somewhat

surprisingly, given the issues involved and the high pitch of popular excitement, voter turnout fell by more than one-third

from the levels in the November presidential election. The short time allotted for campaigning and the uncontested nature

of many of the local races held down the vote. In addition, many conservatives boycotted the elections out of fear of reprisals

if they publicly opposed secession. The key to the victory of the secessionists was their strength in the plantation districts.

They carried four out of five counties in which the slaves comprised a majority of the population and ran weakest in counties

with the fewest slaves. The yeomen, especially in the Alabama and Georgia mountains, were against immediate secession. Characteristically,

they opposed a policy they associated with the black belt planters.

Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana successively seceded

in their January conventions. They were joined by Texas on February 1, 1861. Like falling dominoes, the secession of one state

made it easier for the next to follow. In each convention the secessionists fought back efforts for a cooperative approach

or last-ditch calls for a Southern conference to make final demands on the Republicans. They also defeated attempts by cooperarionists

to submit the secession ordinances to a popular referendum. Only in Texas, where the secessionists were sensitive to the dubious

legality by which they had forced the calling of a convention, was the decision on secession referred to the voters for their

approval. In the end the secession ordinances passed by overwhelming majorities in all the conventions. This apparent unanimity

however, belied the fact that in no state had the immediate secessionists carried enough votes to have made up a majority

in the earlier presidential election. Once the decision for secession was inevitable, the cooperationists voted for the ordinances

in a conscious attempt to impress the Republicans with Southern resolve and unity.

Delegates from the seven seceded states met in Montgomery, Alabama,

in February. Here, on the seventh, they adopted a Provisional Constitution (one closely modeled on the U.S. Constitution)

for an independent Southern government and, on the ninth, elected Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as president. Thus, nearly

a month before Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, the secessionists had achieved one of their major goals. They had a functioning

government in place before the Republicans had even assumed formal control of the Federal government.

| Why did the Southern states secede? |

|

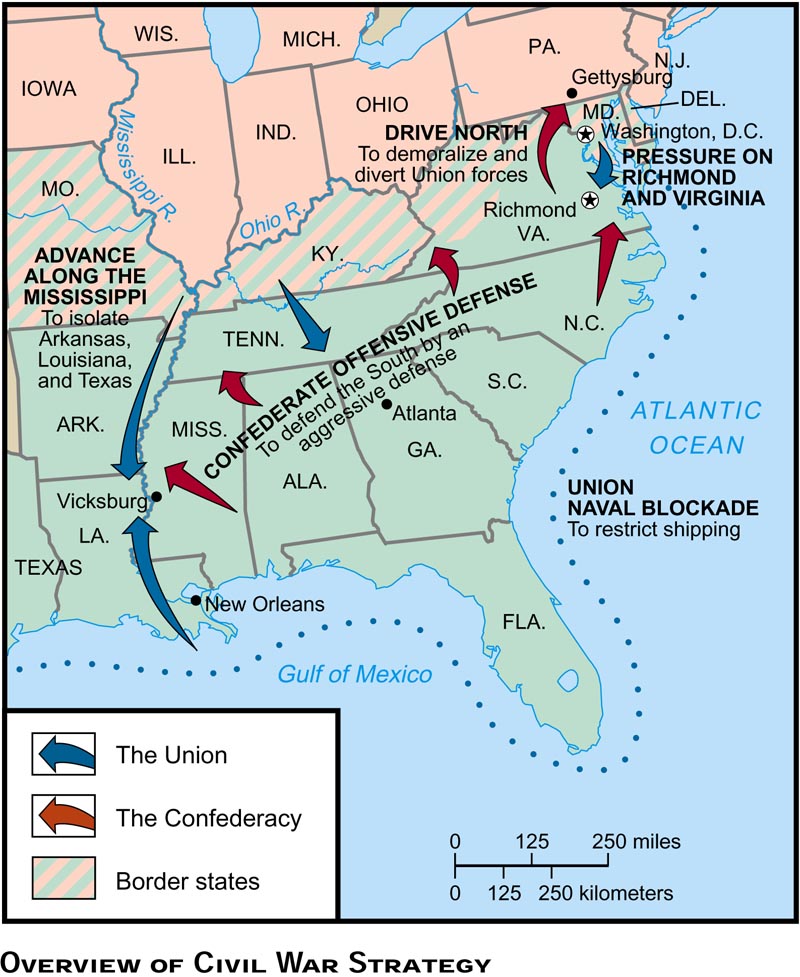

| The Union military Civil War strategy map |

The Upper South Secedes

The collapse of the Crittenden Compromise in late December eliminated the

already slim possibility that the drive toward secession might end with the withdrawal of South Carolina. Still, when Lincoln

took office on March 4, the Republicans had reason to believe that the worst of the crisis was oven February elections in

the Upper South had resulted in Unionist victories. In January the legislatures of five states-- Arkansas, Virginia, Missouri,

Tennessee, and North Carolina--had issued calls for conventions. The secessionists suffered a sharp setback in all the elections.

On February 4, Virginia voters chose to send moderates of various stripes

to their convention by about a three-to-one margin. In yet another defeat for the secessionists, who opposed the measure,

they also overwhelmingly approved a popular referendum on any decision reached by the convention. On February 9, Tennessee

voted against holding a convention. Had one been approved, the Unionists elected would have composed an 80-percent majority.

Arkansas and Missouri voted on February 18, and both elected Unionist majorities. On February 28, North Carolinians repeated

the Tennessee pattern. They rejected the calling of a convention, which, in any event, would have been dominated by Unionists.

By the end of February secession apparently had burnt itself out in

the upper South. It was defeated either by a popular vote or, as in the case of the slave states of Kentucky, Delaware, and

Missouri, by the inability of the secessionists to pressure the legislatures or governors to issue a call for a convention.

Despite fiery speeches and persistent lobbying by secession commissioners appointed by the Confederate government, the antisecessionists

held their ground. In a region that lacked the passionate commitment of the lower South to defending slavery, they were able

to mobilize large Unionist majorities of nonslaveholders. In particular, they succeeded in detaching large numbers of the

Democratic yeomanry from the secessionist, slaveholding wing of their party. The yeomanry responded to the fears invoked by

the Unionists of being caught in the crossfire of a civil war, and nonslaveholders in general questioned how well their interests

would be served in a planter-dominated Confederacy.

A final factor accounting for the Unionist victories in the upper South

was the meeting in Washington of the so-called Peace Convention called by the Virginia legislature. The delegates spent most

of February debating various proposals for additional guarantees for slave property in an effort to find some basis for a

voluntary reconstruction of the Union. Although boycotted by some of the Northern states and all of the states that had already

seceded, the convention raised hopes of a national reconciliation and thereby strengthened the hand of the Unionists in the

upper South. In the end, however, the convention was an exercise in futility. All it could come up with was a modified version

of the Crittenden Compromise. Just before Lincoln's inauguration, Republican votes in the Senate killed the proposal.

Pressures For Action Mount

Throughout March and early April the Union remained in a state of quiescence

that no one expected to last indefinitely. Both of the new governments, Lincoln's and Davis's, were under tremendous pressure

to break the suspense by taking decisive action. Davis was criticized for not moving aggressively enough to bring the upper

South into the Confederacy. Without that region and especially Virginia, it was argued, the Confederacy was but a cipher of

a nation. It had negligible manufacturing capacity and only one-third of the South's free population. It desperately needed

additional slave states to have a viable chance for survival. Just as desperately, Lincoln's government needed to make good

on its claim that the Union was indivisible. Buchanan had been mocked for his indecisiveness, and Lincoln knew that he bad

to take a stand on enforcing Federal authority.

The upper South now became a pawn in a power struggle between Lincoln

and Davis. However much moderates in the upper South wanted to avoid a confrontation that would ignite a war, they were publicly

committed to coming to the assistance of any Southern state that the Republicans attempted to coerce back into the Union.

In short, Unionism in the upper South was always highly conditional in nature. This in turn made the region hostage to events

beyond its control and gave the Confederacy the leverage it needed to pull in additional states.

The only major Federal installations in the Confederacy still under

Federal control when Lincoln became president were Fort Pickens in Pensacola Harbor and Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor.

The retention of these forts thereby became a test of the credibility of the Republicans as the defenders of the Union. By

the same token, the acquisition of these forts was essential if the Confederacy were to lay claim to the full rights of a

sovereign nation.

On March 5, Lincoln learned from Maj. Robert Anderson, the commander at Fort Sumter, that dwindling food supplies

would force an evacuation of the fort within four to six weeks. Lincoln decided against any immediate attempt to save the

fort. On March 12, however, he issued orders for the reinforcement of Fort Pickens. More accessible to the Federal navy because

of its location outside Pensacola Harbor beyond the range of Confederate artillery, Fort Pickens had the additional advantage

of being overshadowed in the public consciousness by Fort Sumter, a highly charged symbol of Federal resolve in the state

that had started secession. Presumably, it could be reinforced with less risk of precipitating a war than could Fort Sumter.

Lincoln's initial decision not to act on Fort Sumter was also a concession to William H. Seward, his secretary of

state. Seward was the chief spokesman for what was called the policy of "masterly inactivity." He believed that Unionists

in the upper South were on the verge of leading a process of voluntary reunion. If the upper South were not stampeded into

joining the Confederacy by a coercive act by the Republicans, Seward argued, an isolated Confederacy would soon have no choice

but to bargain to rejoin the Union. Everything depended, of course, on a conciliatory Republican policy.

In pursuing this strategy, Lincoln temporarily considered a withdrawal

from Fort Sumter in exchange for a binding commitment from the upper South not to leave the Union. Seward then made the mistake

of assuming that evacuation was a foregone conclusion. He was conducting informal negotiations with three Confederate commissioners

who were in Washington seeking a transfer of Fort Pickens and Fort Sumter. On March 15 he informed them through an intermediary

to expect a speedy evacuation of Fort Sumter. When no such evacuation was forthcoming, Confederate leaders felt betrayed,

and they vowed never again to trust the word of the Lincoln administration.

Mounting demands in the North to take a stand at Fort Sumter, combined

with Lincoln's growing disillusionment over Southern Unionism, convinced the president that he would have to challenge the

Confederacy over the issue of Fort Sumter. On March 29 he told his cabinet that he was preparing a relief expedition. He delayed

informing Major Anderson of that decision until after a meeting on April 4 with John Baldwin, a Virginia Unionist. Although

no firsthand account of this meeting exists, the discussion apparently confirmed Lincoln's belief that the upper South could

not broker a voluntary reunion on terms acceptable to the Republican party. The final orders for the relief expedition were

issued on April 6, the day that Lincoln learned that Fort Pickens had not yet been reinforced because of a mix-up in the chain

of command.

News of Lincoln's decision to reinforce Fort Sumter "with provisions

only" reached Montgomery, the Confederate capital, on April 8. The next day Davis ordered Gen. P G. T. Beauregard, the Confederate

commander at Charleston, to demand an immediate surrender of the fort. If Major Anderson refused, Beauregard was to attack

the fort. Davis always felt that war was inevitable, and for months the most radical of the secessionists had been insisting

that a military confrontation would be necessary to force the upper South into secession. Davis was convinced that he had

no alternative but to counter Lincoln's move with a show of force.

| Why did the South secede? |

|

| What was the main cause why the Southern states seceded? |

Confederate batteries opened fire on Fort Sumter on April 12, and the fort

surrendered two days later On April 15 Lincoln issued a call for seventy-five thousand stare militia to put down what he described

as an insurrection against lawful authority. It was this call for troops, and not just the armed clash at Fort Sumter, that

specifically triggered secession in the upper South. The Unionist majorities there suddenly dissolved once the choice shifted

from supporting the Union or the Confederacy to fighting for or against fellow Southerners.

The Virginia convention, which had remained in session after rejecting immediate secession on April 4, passed a secession

ordinance on April 17. Its decision was overwhelmingly ratified on May 23 in a popular referendum. Three other states quickly

followed. A reconvened Arkansas convention voted to go out on May 6. The Tennessee legislature, in a move later ratified in

a popular referendum, also approved secession on May 6. A hastily called North Carolina convention, elected on May 13, took

the Tarheel State out on May 20.

By the late spring of 1861 the stage was set for the bloodiest war in American history The popular reaction to the

firing on Fort Sumter and Lincoln's call for troops unified the North behind a crusade to preserve the Union and solidified,

at least temporarily, a divided South behind the cause of Southern independence.

See also

Sources: Barney, William L. The Confederacy. A Macmillan

Information Now Encyclopedia; Library of Congress; National Archives; National Park Service.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|