|

|

Georgia in the Reconstruction Era

Georgia Reconstruction

Georgia and Reconstruction

At the end of the American Civil War the devastation and disruption in the

state of Georgia was dramatic. Wartime damage, the inability to maintain a labor force without slavery, and miserable weather

had a disastrous effect on agricultural production. The states chief cash crop, cotton, fell from a high of more than 700,000

bales in 1860 to less than 50,000 in 1865, while harvests of corn and wheat were also meager. The state government subsidized

construction of numerous new railroad lines. White farmers turned to cotton as a cash crop, often using commercial fertilizers

to make up for the poor soils they owned. The coastal rice plantations never recovered from the war.

Bartow County

was representative of the postwar difficulties, Property destruction and the deaths of a third of the soldiers caused financial

and social crises; recovery was delayed by repeated crop failures. The Freedmen's Bureau agents were unable to give blacks

the help they needed.

Forty Acres and a Mule

At

the beginning of Reconstruction, Georgia had over 460,000 Freedmen. In January 1865, in Savannah, William T. Sherman issued

Special Field Orders, No. 15 authorizing federal authorities to confiscate 'abandoned' plantation lands in the Sea Islands,

whose owners had fled with the advance of his army, and redistribute them to former slaves. Redistributing 400,000 acres (1,600

kmē) in coastal Georgia and South Carolina to 40,000 freed slaves in forty-acre plots, this order was intended to provide

for the thousands of escaped slaves who had been following his army during his March to the Sea. Shortly after Sherman issued

his order, Congressional leaders convinced President Lincoln to establish the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned

Lands in March 1865. The Freedmen's Bureau, as it came to be called, was authorized to give legal title for 40-acre (160,000

m2) plots of land to freedmen and white Southern Unionists. Tunis Campbell, a free Northern black missionary, was appointed

to supervise land claims and resettlement in Georgia. Over the objections of Freedmen's Bureau chief General Oliver O. Howard,

President Andrew Johnson revoked Sherman's directive in the fall of 1865, after the war had ended, returning these lands to

the planters who had previously owned them.

Presidential Reconstruction

On

Georgia's farms and plantations, wartime destruction, the inability to maintain a labor force without slavery, and miserable

weather had a disastrous effect on agricultural production. The states chief money crop, cotton, fell from a high of more

than 700,000 bales in 1860 to less than 50,000 in 1865, while harvests of corn and wheat were also meager. After the war,

new railroad lines and commercial fertilizers increased cotton production in Georgia's upcountry, but the coastal rice plantations

never recovered from the war.

Many emancipated slaves flocked to towns, where they encountered overcrowding and shortages

of food, large numbers dying of epidemic diseases. The Freedmen's Bureau returned much black labor to the field, mediating

a contract-labor system between white landowners and their black workers, usually their former slaves. Taking advantage of

educational opportunities available for the first time, within a year, at least 8,000 former slaves were attending schools

in Georgia, established with northern philanthropy.

In mid-June 1865, Andrew Johnson appointed as provisional governor

his friend and fellow Unionist, James Johnson, a Columbus lawyer who sat out the war. Delegates to a constitutional convention,

meeting in Milledgeville in October, abolished slavery, repealed the Ordinance of Secession, and repudiated the Confederacy

debt. The General Assembly, while alone among ex-Confederate states in refraining from enacting a harsh Black Code, assumed

newly freed slaves would enjoy only the limited freedom of the prewar period's 'free persons of color,' and enacted a constitutional

amendment outlawing interracial marriage. On November 15, 1865, Georgia elected a new governor, congressmen, and state legislators.

Voters repudiated most Unionist candidates, electing to office many ex-Confederates, although several of these-including the

new governor, former Whig Charles J. Jenkins-initially opposed secession. The new state legislator created a political firestorm

in Washington by electing to the Senate Alexander Stephens and Herschel Johnson, respectively, Vice-President and Senator

of the Confederacy. Neither Stephens, Johnson nor any of Georgia's House delegation were allowed to take their seats.

| Georgia, Civil War, and Reconstruction Map |

|

| Georgia Reconstruction Map |

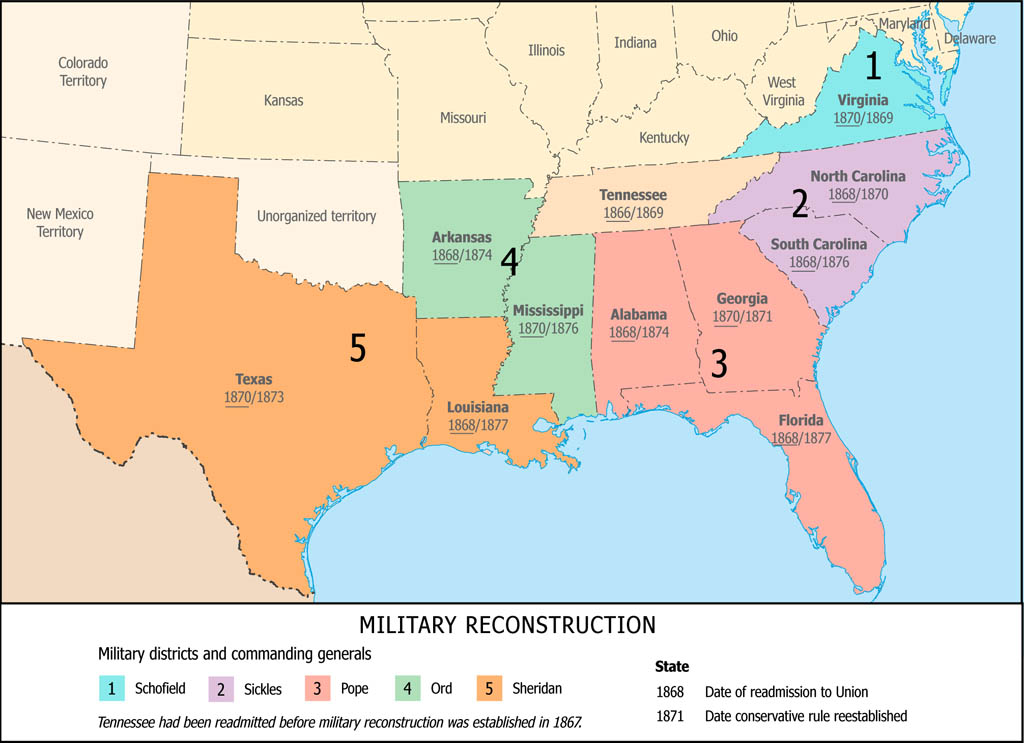

Congressional

Reconstruction

Andrew Johnson's decision in August 1866 to restore the former Confederate states to the Union

was criticized by the Radical Republicans in Congress, who, in March 1867, passed the First Reconstruction Act, placing the

South under military occupation. Georgia, along with Alabama and Florida, became part of the Third Military District, under

the command of General John Pope. Radical Republicans also passed an ironclad oath which prevented ex-Confederates from voting

or holding office, replacing them with a coalition of Freedmen, Carpetbaggers, and Scalawags, mostly former Whigs who had

opposed secession.

As directed by Congress, General John Pope registered Georgia's eligible

white and black voters, 95,214 and 93,457 respectively. From October 29 through November 2, 1867, elections were held for

delegates to a new constitutional convention, held in Atlanta rather than the state capital of Milledgeville, to prevent the

interference of the ex-Confederates. In January 1868, after Georgia's first elected governor after the end of the war, Charles

Jenkins, refused to authorize state funds for the racially integrated state constitutional convention, his government was

dissolved by Pope's successor General George Meade and replaced by a military governor. This coup galvanized white resistance

to the Reconstruction, fueling the growth of the Ku Klux Klan. Grand Wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest visited Atlanta several

times in early 1868 to help set up the organization. In Georgia, the Klan was led by John Brown Gordon, a charismatic General

in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Freedmen's Bureau agents reported 336 cases of murder or assault with intent to kill against

freedmen across the state from January 1 through November 15 of 1868.

In July 1870, Georgia was readmitted to the Union,

the newly elected General Assembly ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, and a Republican governor, New York native Rufus Bullock,

was inaugurated. The states Democrats-including former Confederate leaders Robert Toombs and Howell Cobb-denounced the policies

of the Reconstruction in a mass-rally in Atlanta described as the largest in the states history. The principal target of the

rally, Joseph E. Brown, Georgia's Governor under the Confederacy, who became a Republican and a delegate to the Chicago convention

that had nominated Union general Ulysses S. Grant for president, declared that the state's constitution did not allow blacks

to hold office. In September, white Republicans joined with the Democrats in expelling the three black senators and twenty-five

black representatives in the lower house from the General Assembly (see E.C. Woolley, The Reconstruction of Georgia p. 94).

A week later in the southwest Georgia town of Camilla, white residents attacked a black Republican rally, killing twelve people.

These

developments led to calls for Georgia's return to military rule, which increased after Georgia was one of only two ex-Confederate

states to vote against Grant in the Presidential election of 1868. The expelled black legislators, led by Tunis Campbell and

Henry McNeill Turner, lobbied for federal intervention in Washington. In March 1869 Governor Bullock, hoping to prolong Reconstruction,

"engineered" the defeat of the Fifteenth Amendment. The same month the U.S. Congress once again barred Georgia's representatives

from their seats, causing military rule to resume in December 1869. In January 1870, Gen. Alfred H. Terry, the final commanding

general of the Third District, purged the General Assembly's ex-Confederates, replaced them with the Republican runners-up,

and reinstated the expelled black legislators, creating a large Republican majority in the legislature.

End of Reconstruction

Georgia

Democrats despised the 'Carpetbagger' administration of Rufus Bullock, accusing two of his friends, Foster Blodgett, superintendent

of the state's Western and Atlantic Railroad, and Hannibal I. Kimball, owner of the Atlanta opera house where the state legislature

met, of embezzling state funds. His efforts to prolong military rule caused considerable divisions in the states party, while

black politicians complained that they did not receive an adequate share of patronage. In February 1870 the newly constituted

legislature ratified the Fifteenth Amendment and chose new Senators to send to Washington. On July 15, Georgia became the

last former Confederate state readmitted into the Union. The Democrats subsequently won commanding majorities in both houses

of the General Assembly. Governor Rufus Bullock fled the state in order to avoid impeachment. With the voting restrictions

against former Confederates removed, Democrat and ex-Confederate Colonel James Milton Smith was elected to complete Bullock's

term. By January 1872 Georgia was fully under the control of the Redeemers, the state's resurgent white conservative Democrats.

The

so-called Redeemers used terrorism to strengthen their rule. The expelled African American legislators were particular targets

for their violence. African American legislator Abram Colby was pulled out of his home

by a mob and given 100 lashes with a whip. His colleague Abram Turner was murdered. Other African American lawmakers were

threatened and attacked.

|

|

|

|

|

Sources: Brown, Barry L. and Gordon R. Elwell. Crossroads of Conflict: A

Guide to Civil War Sites in Georgia (2010); Bryan, T. Conn. Confederate Georgia (1953), the standard scholarly survey; DeCredico,

Mary A. Patriotism for Profit: Georgia's Urban Entrepreneurs and the Confederate War Effort (1990); Fowler, John D. and David

B. Parker, eds. Breaking the Heartland: The Civil War in Georgia (2011); Gourley, Bruce T. Diverging Loyalties: Baptists in

Middle Georgia During the Civil War (2011); Harrington, Hugh T. Civil War Milledgeville: Tales from the Confederate Capital

of Georgia (2005); Hill, Louise Biles. Joseph E. Brown and the Confederacy. (1972); Inscoe, John C. (2011). The Civil War

in Georgia: A New Georgia Encyclopedia Companion. University of Georgia Press; Johnson, Michael P. Toward A Patriarchal Republic:

The Secession of Georgia (1977); Jones, Charles Edgeworth (1909). Georgia in the War: 1861-1865. Augusta, Georgia: Foote and

Davies; Miles, Jim. To the Sea: A History and Tour Guide of the War in the West, Sherman's March Across Georgia and Through

the Carolinas, 1864-1865 (2002); Mohr, Clarence L. On the Threshold of Freedom: Masters and Slaves in Civil War Georgia (1986);

Parks, Joseph H. Joseph E. Brown of Georgia (Louisiana State University Press) (1977); Wallenstein, Peter. "Rich Man's War,

Rich Man's Fight: Civil War and the Transformation of Public Finance in Georgia," Journal of Southern History (1984); Weitz,

Mark A. A Higher Duty: Desertion among Georgia Troops during the Civil War (2005); Wetherington, Mark V. Plain Folk's Fight:

The Civil War and Reconstruction in Piney Woods Georgia (2009); Whites, Lee Ann. The Civil War as a Crisis in Gender: Augusta,

Georgia, 1860-1890 (2000); Williams, David. Rich Man's War: Class, Caste, and Confederate Defeat in the Lower Chattahoochee

Valley (1998); Williams, Teresa Crisp, and David Williams. "'The Women Rising': Cotton, Class, and Confederate Georgia's Rioting

Women," Georgia Historical Quarterly (2002).

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|