|

|

Georgia in the American Civil War

Georgia Civil War History

Introduction

Georgia was established in 1732

as the Thirteenth Colony. Named after King George II of Great Britain, Georgia became the fourth state of the Union after

ratifying the United States Constitution on January 2, 1788. It declared its secession from the Union on January 21, 1861,

and was one of the original seven Confederate states. It was the last state to be restored to the Union, on July 15, 1870.

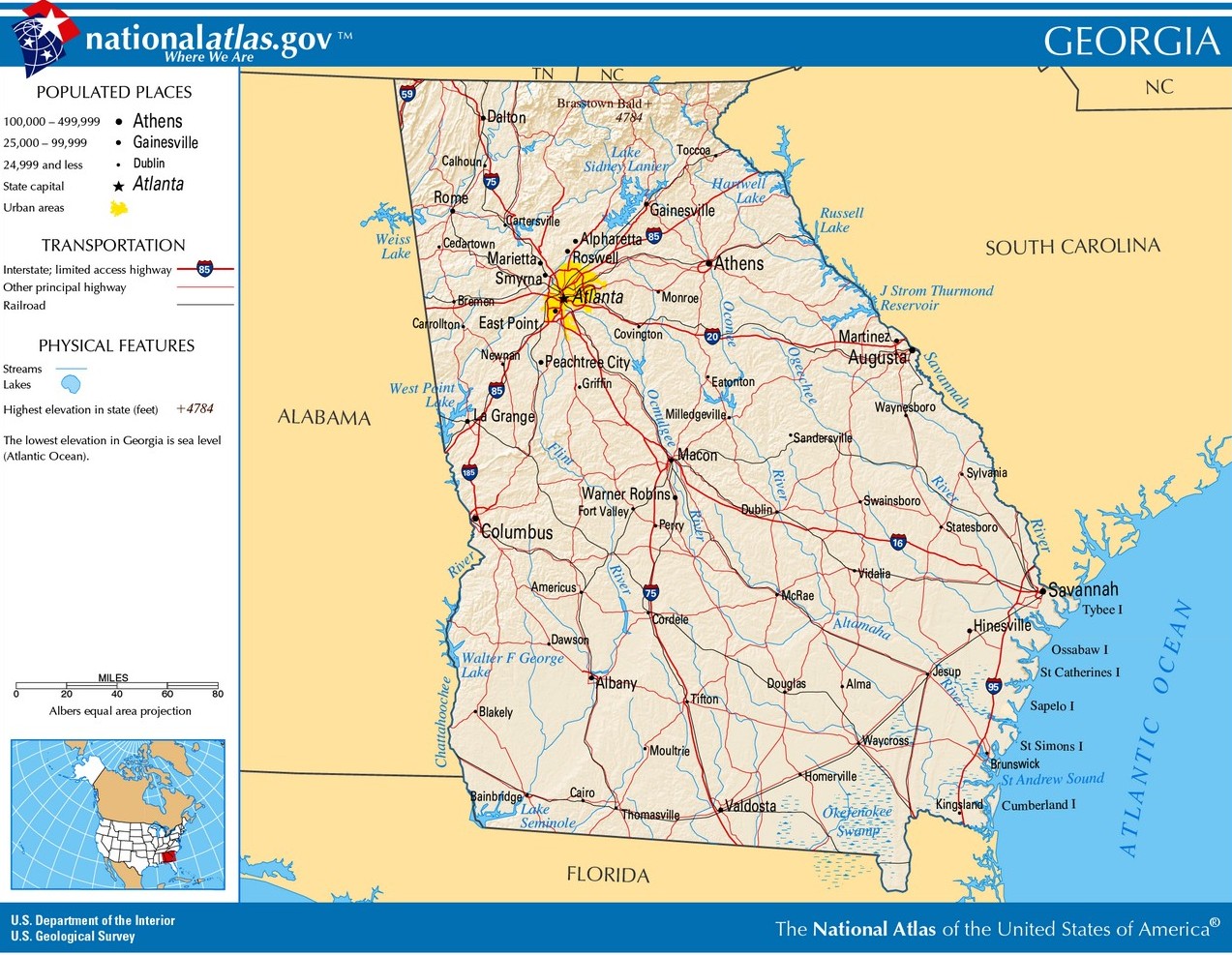

Georgia is a state located in

the southeastern United States and it is bordered on the south by Florida; on the east by the Atlantic Ocean and South Carolina;

on the west by Alabama; and on the north by Tennessee and North Carolina. The northern part of the state is in the Blue Ridge

Mountains, a mountain range in the Appalachian Mountains system.

At the time of European

colonization of the Americas, the historic Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee and Muskogean-speaking Creek and Yamasee Indians lived

in what is now Georgia. The Cherokee spread southward along the Ridge and Valley Appalachians, occupying lands reaching to

the upper Chattahoochee, which formed the southern boundary of their lands, stretching all the way to the Ohio River. The Creek or Muscogee were a loose confederation of tribes descended from the Mississippian

culture people. They were divided between the Lower Creeks along the Ocmulgee, Flint and the lower Chattahoochee rivers, and

the more remote Upper Creeks along the Coosa and Alabama rivers. The Yamasee occupied the coastal areas along the Savannah

River.

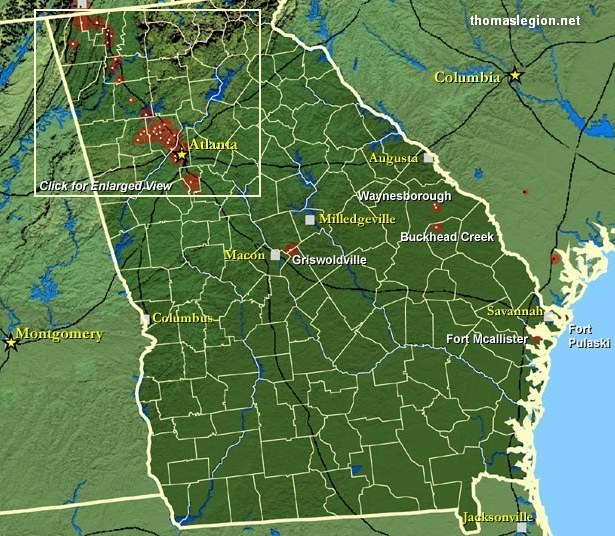

| Georgia Civil War Map |

|

| Georgia, Slavery, Secession, and Civil War Map |

In 1829, gold was discovered in the north Georgia mountains, resulting

in the Georgia Gold Rush, the second gold rush in U.S. history. A Federal mint was established in Dahlonega, Georgia, and

continued to operate until 1861. During this time, Cherokee Indians owned their ancestral land, operated their own government

with a written constitution, and did not recognize the authority of the state of Georgia. An influx of white settlers pressured

the U.S. government to expel them. The dispute culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830, under which all eastern tribes

were sent west to Indian reservations in present-day Oklahoma. In Worcester v. Georgia, the Supreme Court in 1832 ruled that

states were not permitted to redraw the boundaries of Indian lands, but President Andrew Jackson and the state of Georgia

ignored the ruling. In 1838, his successor, Martin Van Buren dispatched Federal troops to round up the Cherokee and deport

them west of the Mississippi. This forced relocation, beginning in White County, became known as the Trail of Tears and led

to the death of over 4,000 Cherokees.

In 1794, Eli Whitney, a Massachusetts-born

artisan residing in Savannah, patented a cotton gin, mechanizing the separation of cotton fibres from their seeds. The Industrial

Revolution had resulted in the mechanized spinning and weaving of cloth in the world’s first factories in the north

of England. Fueled by the soaring demands of British textile manufacturers, King Cotton quickly came to dominate Georgia and

the other Southern states. Although Congress banned the slave trade in 1808, Georgia's slave population continued to grow

with the importation of slaves from the plantations of the South Carolina Low Country and Chesapeake Tidewater, increasing

from 149,656 in 1820 to 280,944 in 1840. A small population of free blacks developed, mostly working as artisans. The Georgia

legislature unanimously passed a resolution in 1842 declaring that free blacks were not citizens. In 1868, with the passage

of the 14th Amendment, blacks became U.S. citizens. American Indians, however, would not receive citizenship

until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.

Slaves worked the fields

in large cotton plantations, and the economy of the state became dependent on the institution of slavery. Requiring little

cultivation, most efficiently grown on large plantations by large (slave) workforces, and easy to transport, cotton proved

ideally suited to the inland frontier. The lower Piedmont or 'Black Belt' counties – comprising the middle third of

the state and initially named for the region's distinctively dark and fertile soil – became the site of the largest

and most productive cotton plantations. By 1860, the slave population in the Black Belt was three times greater than that

of the coastal counties, where rice remained the principal crop. The upper Piedmont was settled mainly by white yeoman farmers

of English descent. While there were also many smaller cotton plantations, the proportion of slaves was lower in north Georgia

than in the coastal and Black Belt counties, but it still ranged up to 25% of the population. In 1860 in

the state as a whole, enslaved African Americans comprised 44% of the population of slightly more

than one million.

On

January 18, 1861, Georgia seceded from the Union during the American Civil War (1861-1865) but kept the name "State of

Georgia" when it joined the newly formed Confederacy in February. During the war, Georgia sent nearly 100,000 soldiers to

battle, mostly to the armies in Virginia. The state transitioned from cotton to food production, but severe transportation

difficulties eventually restricted supplies. Early in the war, the state's 1,400 miles of railroad tracks provided a frequently

used means of moving supplies and men but by the middle of 1864 much of these lay in ruins or in Union hands. By war's

end in 1865, while tens of thousands of troops were returning home, the state's infrastructure, from Atlanta to

Savannah, was now in ruins.

Slavery

Slavery in Georgia is known

to have been practiced by the original or earliest known residents of the future colony and state for centuries prior to European

settlement. However, the penal colony, under James Oglethorpe, is known to have been the only British colony to have banned

slavery before legalizing it (1735) with the help of George Whitfield. It was eventually legalized by royal decree in 1751.

Georgia also figures significantly in the history of American slavery because of Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin

in 1793. It was first demonstrated to an audience on Revolutionary War hero Gen. Nathanael Greene's plantation, near Savannah.

The cotton gin's invention led both to the explosion of cotton as a cash crop as well as to the revitalization of African

slavery in the Southern United States, which soon became dependent upon the growth and sale of cotton to manufacturers in

the Northern United States and abroad.

Slavery was officially abolished

by the Thirteenth Amendment which took effect on December 18, 1865. Slavery had been theoretically abolished by President

Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation which proclaimed, in 1863, that only slaves located in territories that were in

rebellion from the United States were free. The proclamation excluded the slaveholding Border States, however, since

they were never formally in rebellion. Since the U.S. government was not in effective control of many of these territories

until later in the war, many of these slaves proclaimed to be free by the Emancipation Proclamation were still held in servitude

until those areas were under Union control.

Secession

Governor Joseph E. Brown was

a leading secessionist in 1860 and a firm believer in states' rights. Although Georgia declared its secession

from the Union on January 21, 1861, Brown resisted many of the newly formed Confederacy's policies, including Confederate

conscription. "To fight off invaders," Brown tried to keep as many soldiers as possible within the state. He also challenged

Confederate impressment of animals, goods, and slaves. Several other governors followed his lead. Seven states (South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas)

declared their secession from the United States before Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861. After Lincoln's subsequent

call for 75,000 troop, aka Lincoln's Call For Troops, on April 15, to subdue the seceded states, four more states (Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North

Carolina) declared their secession.

| Georgia Civil War Map |

|

| Georgia Secession Map |

Civil War

According to the 1860 U.S. census, Georgia had a free population of 595,088

and an additional slave population of 462,198.

Approximately 100,000 Georgians served in the Confederate Army, and during

the course of the conflict the state suffered 18,253 killed and several thousands more wounded. A compilation made

from the official rosters of the Confederate Armies as they stood at various battles, and at various dates covering the entire

period of the war, shows that Georgia kept the following number of organizations in almost continuous service in the

field: 68 regiments, and 17 battalions of infantry; 11 regiments, and 2 battalions of cavalry; 1 regiment, and 1 battalion

of partisan rangers; 2 battalions of heavy artillery; and 28 batteries of light artillery.

Thinking the state safe from invasion, the Confederates built several

small munitions factories in Georgia, and it constructed prisons which later detained tens of thousands of Union

prisoners. The largest prisoner-of-war camp in the North or South was in Andersonville, Georgia. Camp Sumter, commonly

known as Andersonville, proved a death camp because of severe lack of supplies,

food, water, and medicine. In early 1861, Georgia joined the Confederacy and became a major theater of the Civil War. Although

major battles took place at Chickamauga, Kennesaw Mountain, and Atlanta, in December 1864, a large swath of the state from Atlanta to Savannah was destroyed

during General William Tecumseh Sherman's March to the Sea.

By summer 1861 the tight Union

naval blockade virtually shut down the export of cotton and the import of manufactured items. Foods that normally came

by rail from the North never arrived. The governor and legislature pleaded with planters to grow less cotton and more food.

They refused, because at first they thought the Yankees would not or could not fight. Then they saw cotton prices in Europe

were soaring and they expected Europe to soon intervene and break the blockade. The legislature imposed cotton quotas and

made it a crime to grow an excess, but the food shortages only worsened, especially in the towns. Poor women took matters

in their own hands in more than two dozen episodes across the state when they raided stores and captured supply wagons to

obtain such necessities as bacon, corn, flour, and cotton yarn. As conditions at home worsened late in the war, more soldiers

came to realize their duty to protect their homes meant they had to desert and return home.

Georgia soil was relatively free from the baptism of fire until late 1863.

A total of nearly 550 battles and skirmishes occurred within the state, with the majority in the last two years of the conflict.

The first major battle in Georgia was a Confederate victory at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863—it was the last major

Confederate victory in the west. In 1864, Union General William T. Sherman's armies invaded Georgia as part of the Atlanta

Campaign. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston fought a series of battles, the largest being the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain,

trying to delay Union armies for as long as possible as he retreated toward Atlanta. Johnston's replacement, Gen. John Bell

Hood, attempted several unsuccessful counterattacks at the Battle of Peachtree Creek and the Battle of Atlanta, but Sherman

captured Atlanta on September 2, 1864.

In November, Sherman stripped his army of non-essentials, and burned Atlanta

and left it to the Confederates. He began what was later named Sherman's March to the Sea, living off the land while burning

plantations, wrecking railroads, and killing the livestock. Thousands of escaped slaves followed him as he entered Savannah

on December 22. After the loss of Atlanta, the governor withdrew the state's militia from the Confederate forces to harvest

crops for the state and the army.

| Civil War Battles Around Atlanta |

|

| Major Civil War Actions Around Greater Atlanta |

| Major Civil War Battles of Georgia |

|

| Principal Civil War Battlefields of Georgia |

Sherman's March was devastating to Georgia and the Confederacy in terms

of economics and psychology. Sherman himself estimated that the campaign had inflicted $100 million (about $1.4 billion in 2010 dollars) in destruction, about one fifth of which "inured to our advantage"

while the "remainder is simple waste and destruction." His army wrecked 300 miles of railroad and numerous bridges and miles

of telegraph lines. It seized 5,000 horses, 4,000 mules, and 13,000 head of cattle. It confiscated 9.5 million pounds of corn

and 10.5 million pounds of fodder, and destroyed uncounted cotton gins and mills.

Sherman's campaign of total war extended

to Georgia civilians. In July 1864, during the Atlanta Campaign, General Sherman ordered approximately 400 Roswell mill workers, mostly women,

arrested as traitors and shipped as prisoners to the North with their children. There is little evidence that more than a

few of the women ever returned home. In December 1864, Sherman captured Savannah and in January 1865 he began his Campaign of the Carolinas. However, there were still several small fights in Georgia after his departure.

On April 16, 1865, the Battle of Columbus was fought on the Georgia-Alabama border. In 1935 the state legislature officially

declared this engagement as the "last battle of the War Between the States."

The memory of Sherman's March became iconic and central to the memory of

"The Lost Cause." The crisis was the setting for Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel Gone with the Wind and the subsequent 1939

film. Most important were many "salvation stories" that tell not what Yankee soldiers destroyed, but what was saved by the

quick thinking and crafty women on the home front, or perhaps was saved by Northerners' appreciation of the beauty of homes

and the charm of Southern women.

The war left most of Georgia devastated, with many war dead and wounded,

and the state's economy in shambles. All slaves were emancipated in 1865, and Reconstruction started immediately after the

hostilities ceased. The state remained poor and destitute well into the twentieth century. Georgia did not re-enter the Union

until June 15, 1870, more than two years after South Carolina was readmitted. Georgia was the last of the Confederate States

to re-enter the Union.

After the war, Georgians endured a period of economic hardship. Reconstruction

was a period of military occupation and biracial Radical republican rule that attempted to bring about equal rights to the

freed slaves (Freedmen) and institute economic initiatives. The end of Reconstruction and return of white domination of the

legislature marked the beginning of the Jim Crow era, in which whites imposed second-class legal, social and economic status

on blacks.

| Georgia Civil War Map of Battles |

|

| Georgia Civil War Map of Battlefields |

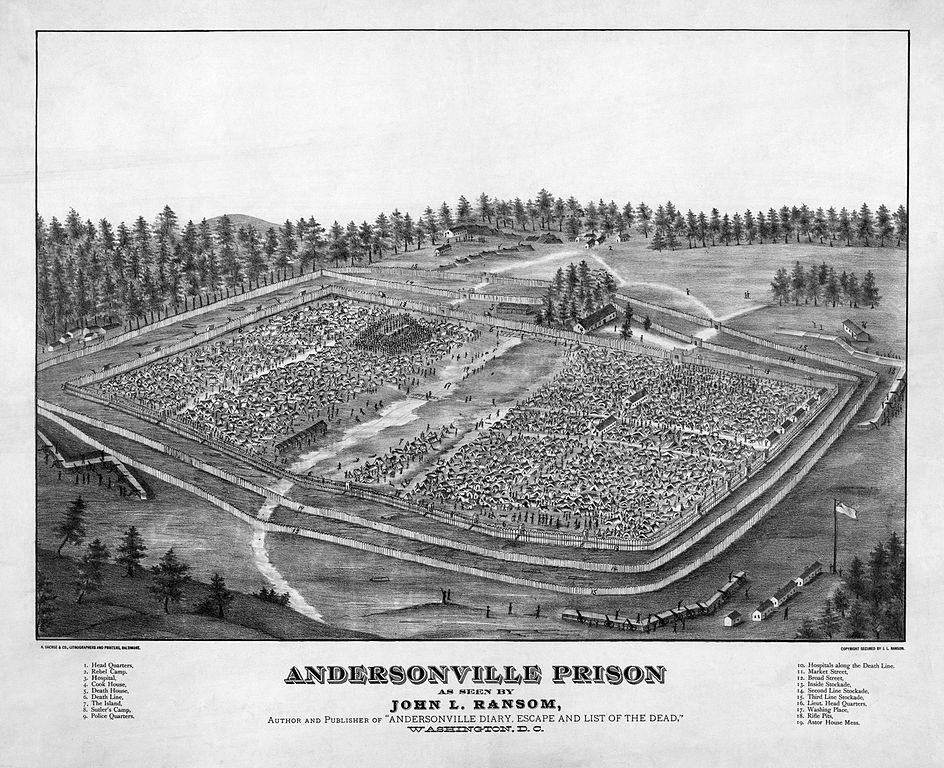

Andersonville Prison

In

1864, the Confederate government relocated Union prisoners-of-war from Richmond, Virginia, to the town of Andersonville, in

remote southwest Georgia. It proved a death camp because of severe lack of supplies, food, water, and medicine. During the

15 months the Andersonville prison camp existed, it detained 45,000 Union soldiers, and at least 13,000 died from disease,

malnutrition, starvation, or exposure. At its height, the death rate surpassed 100 persons daily. Postwar, the camp's commanding

officer, Captain Henry Wirz, became the only Confederate to be tried and executed as a war criminal; a fate that had evaded

Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Andersonville, or Camp Sumter as it was officially known, was the largest

of several military prisons established during the Civil War. It was built in 1864 after Confederate leaders decided to move

the many Union prisoners in Richmond, Virginia, to a location away from the war. A site was needed where the prisoners could

be guarded by fewer men, there would be less chance of military raids to free them, and food would be more abundant. The town

of Andersonville was located on a railroad line approximately 65 miles southwest of Macon, Georgia. The village, near a small

stream and in a remote agricultural area, seemed ideal. Construction of the 16 1/2 acre prison camp began in January 1864.

Pine logs, 20 feet in length, were placed five feet deep in the ground to create a wooden stockade. In June 1864, the prison

was enlarged to 26 1/2 acres. The prison proper was in the shape of a rectangle 1,620 feet long and 779 feet wide. Sentry

boxes, or "pigeon roosts," were placed at 30 yard intervals along the top of the stockade. Along the interior of the stockade,

19 feet from the stockade wall, was a line of small wooden posts with a wood rail on top. This was the "deadline." Any prisoner

who crossed the deadline could be shot by guards stationed in the sentry boxes. Small earthen forts around the exterior of

the prison were equipped with artillery to put down disturbances within the compound and to defend against Union cavalry attacks.

The first prisoners arrived on February 25, 1864, while the stockade wall

was still under construction. Small earthworks, equipped with artillery, overlooked the compound. Designed to hold 10,000

prisoners, the prison was soon overcrowded, holding 22,000 by June. Although the prison was enlarged, the number of prisoners

continued to swell. By August 1864, more than 32,000 prisoners were confined at Andersonville.

Hindered by deteriorating economic conditions, an inadequate transportation

system, and the need to concentrate all available resources on its own army, the Confederate government was unable to provide

adequate housing, food, clothing, shelter, and medical care for its captives. These conditions, along with a breakdown of

the prisoner exchange system, created much suffering and a high mortality rate. More than 45,000 Union soldiers were sent

to Andersonville during the 14 months of the prison's existence. Of these, 12,912 died from disease, malnutrition, overcrowding,

or exposure. They were buried in shallow trenches, shoulder to shoulder, in a crude cemetery near the prison.

In September 1864, when General William T. Sherman's forces occupied Atlanta,

and a Union cavalry column threatened Andersonville's security, most of the prisoners were moved to other camps in Georgia

and South Carolina. The prison operated on a much smaller scale for the remaining six months of the war.

Following the Confederate surrender in April 1865, Clara Barton, later founder

of the American Red Cross, and Dorence Atwater, a former prisoner assigned as a parolee to keep burial records for prison

officials, visited the cemetery at Andersonville to identify and mark the graves of the Union dead. During the war Atwater

had labeled the soldiers by name and number after their deaths. Through Barton and Atwater's efforts, the cemetery was dedicated

as Andersonville National Cemetery in August 1865.

Another important event that occurred after the war was the arrest and trial

of Captain Henry Wirz, the commandant of the prison. Wirz was arrested and charged with conspiring to "impair and injure the

health and destroy the lives of Federal prisoners" and with "murder in violation of the laws of war." At his trial in Washington

D.C., many former prisoners testified against him, vividly describing conditions at the prison. The former prisoners (and

one who testified but was never actually a prisoner) blamed Wirz as the cause of their suffering. Historical documents, however,

attest to the fact that prison officials attempted to acquire supplies for the prisoners but were severely hampered by the

need to use supplies for the military and war effort. The question of whether or not Wirz could have done more to make life

more bearable for the prisoners is still debated today. Was he simply a convenient scapegoat? Because of public outrage and

indignation in the North over conditions at Andersonville, Captain Henry Wirz was found guilty of war crimes and was hanged

on November 10, 1865. It has been said that Wirz was the last casualty of Andersonville.

| Georgia and the Civil War |

|

| Andersonville Prison |

Reconstruction

Wartime destruction and a subsequent economic depression forced many of

the state's rice plantations into bankruptcy. New railroad lines and commercial fertilizers increased cotton cultivation in

Georgia's upcountry, but rice growers never recovered, and the state's coastal plantation homes, as Northerner Edward King

reported,were abandoned "like sorrowful ghosts lamenting the past." However, freed slaves found more landowning opportunities

in lowcountry Georgia.

At the beginning of the period of Reconstruction, Georgia had more than

460,000 freedmen. Slaves had been 44% of the state's population in 1860.

Seventy-three years after ratification of the U.S. Constitution, Georgia

had seceded from the Union and joined other Southern states to form the Confederate States of America in February 1861. War

erupted on April 12, 1861 and Georgia contributed nearly one hundred thousand soldiers to the war effort. The first major

battle in Georgia was the Battle of Chickamauga, a Confederate victory, and the last major Confederate victory in the west.

In 1864, William T. Sherman's armies invaded Georgia as part of the Atlanta Campaign; Sherman's March to the Sea devastated

a wide swath from Atlanta to Savannah in late 1864.

At war's end the devastation and disruption in every part of the state

was dramatic. Wartime damage, the inability to maintain a labor force without slavery, and miserable weather had a disastrous

effect on agricultural production. The states chief money crop, cotton, fell from a high of more than 700,000 bales in 1860

to less than 50,000 in 1865, while harvests of corn and wheat were also meager. After the war, the state subsidized construction

of numerous new railroad lines. Use of commercial fertilizers increased cotton production in Georgia's upcountry, but the

coastal rice plantations never recovered from the war.

In January 1865, William T. Sherman issued Special Field Orders, No.

15 authorizing Federal authorities to confiscate abandoned plantations in the Sea Islands and redistribute land in smaller

plots to former slaves. Later that year, after succeeding Lincoln in the presidency, Andrew Johnson revoked the order and

returned the plantations to their former owners.

After the Civil War, many former slaves moved from rural areas to

Atlanta, where economic opportunities were better. There, they established their own communities. Other migrations involved

blacks moving from plantations to adjacent small towns and communities. A new Federal agency the Freedmen's Bureau helped

blacks negotiate labor contracts, and set up schools and churches.

Andrew Johnson's decision to restore the former

Confederate states to the Union, without requirements for political change, was criticized by Radical Republicans in Congress.

In March 1867, Congress passed the First Reconstruction Act to place the South under military occupation and rule. Along with

Alabama and Florida, Georgia was included in the Third Military District, under the command of General John Pope. Military

rule lasted less than a year and involved holding elections in which black men could vote for the first time. The electoral

role in 1867 included 102,000 eligible white men, and 99,000 eligible blacks. Radical Republicans in Congress required ex-Confederates

to take an ironclad oath of loyalty or be prevented from holding office. The legislature was controlled by a coalition of

newly enfranchised freedmen, Northerners (carpetbaggers), and white Southerners (disparagingly called scalawags). The latter

were mostly former Whigs who had opposed secession.

The voters elected delegates to write a new constitution in 1868; 20% of

the delegates were black. In July 1868, the newly elected General Assembly ratified the Fourteenth Amendment; a Republican

governor, Rufus Bullock, was inaugurated, and Georgia was readmitted to the Union. The state's Democrats, including former

Confederate leaders Robert Toombs and Howell Cobb, convened in Atlanta to denounce Reconstruction. Theirs was described as

the largest mass rally held in Georgia. In September, white Republicans joined with the Democrats in expelling all thirty-two

black legislators from the General Assembly. Angered at black holding powerful roles in the legislature and at the county

level, some ex-Confederates organized paramilitary groups, especially the Ku Klux Klan. Freedmen's Bureau agents reported

336 cases of murder or assault with intent to kill perpetrated against freedmen across the state from January 1 through November

15 of 1868.

| Georgia Civil War Battlefield Map |

|

| High Resolution Terrain Map of Georgia |

In 1868, under Reconstruction, Georgia became the first state in

the South to implement the convict lease system. It generated revenue for the state by leasing out the prison population,

many of whom were black, to work for private businesses and citizens. Prisoners did not receive income for their labor. In

this manner, railroad companies, mines, turpentine distilleries and other manufacturers supplemented their workforce with

unpaid convict labor. This helped to hasten Georgia's transition to industrialization. Under the convict release system, employers

were legally obliged to provide humane treatment to the laborers. However, some mistreatment was reported. One prominent beneficiary

of this system was the Republican jurist and politician Joseph E. Brown, whose railroads, coal mines and iron works supplemented

their workforce with convict labor.

The activity of political groups opposed to Reconstruction prompted Republicans

and others to call for the return of Georgia to military rule. Georgia was one of only two ex-Confederate states to vote against

Ulysses S. Grant in the presidential election of 1868. In March 1869, the state legislature defeated ratification of the Fifteenth

Amendment.

That same month, the U.S. Congress, citing election fraud, barred Georgia's representatives from taking

their seats. This culminated in military rule being re-imposed in December 1869. In January 1870, Gen. Alfred H. Terry, the

final commanding general of the Third District, purged the General Assembly of ex-Confederates. He replaced them with Republican

runners-up and reinstated expelled black legislators. This militarily imposed General Assembly had a large Republican majority.

In

February 1870, the newly constituted legislature ratified the Fifteenth Amendment and chose new Senators to send to Washington.

On July 15, Georgia became the last former Confederate state readmitted into the Union. After

military rule ended, Democrats won commanding majorities in both houses of the General Assembly. Some Reconstruction-era black

legislators held on to their seats, the last one serving until 1907. Under threat of impeachment, Republican governor Rufus

Bullock fled the state.

See also

|

|

|