|

|

American Civil War History

Union and Confederate Army of Infantry, Cavalry, and

Artillery

American Civil War

Union and Confederate Military Forces

| American Civil War |

|

| American Civil War caused more deaths than all previous US wars combined |

American

Civil War (1861–1865) was a major war between the United States ("Union") and eleven

Southern states ("Confederacy"), which declared that they had a right to secession and formed the Confederate States of America, led by President Jefferson Davis.

The Union included free states and Border States and was led by President Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party. Although the Border States were under Union control,

they supplied the South with tens-of-thousands of troops.

Although the South strongly believed in States' Rights (Bill of Rights and the 10th Amendment) according to the United States Constitution and believed that it entitled them to a right of secession, the Republicans rejected any such right

while they also opposed the expansion of slavery into territories owned by the United States.

Unlike most international disputes and wars, the Civil War soldier, whether from the North (Union) or South (Confederacy), had much in common. Some opposing soldiers, for example, including high ranking

generals and lowly privates, spoke the same language, enjoyed the same music, food and hobbies, claimed the same

home state, attended the same university, had the same surname, and were even raised in the same house. Some soldiers

were brothers but found themselves standing firm and on opposing sides of the battlefield, causing

many to refer to the conflict as the Brothers War. Soldiers' motives for fighting in the conflict varied, as well as the war's

causes, divisions, and sectional strife that led to the four year Civil War. See also Causes and Origins of the American Civil War and American

Civil War.

The American Civil War came during a period of evangelical fervor and increasing religious

diversity in America. When war commenced, churchgoers both North and South were equally sure that God was on their side, and

both presidents invoked divine sanction for their cause. Others, such as Quakers, had to weigh the value of patriotism versus

an opposition to war.

The Civil War witnessed divided families and communities, and it produced outlaws and community

feuds that would endure well beyond the conclusion of the conflict. War was difficult, but to know, or to even view, your

brother, father, nephew, grandfather, or uncle on the opposing side of the battlefield was extremely heartbreaking for many.

So how did the soldiers cope knowing that kinfolk and relatives were on the opposite side? Since many viewed the war in a

spiritual and religious perspective, it soothed their conscious by believing that the war was ordained by the Heavenly Father,

and that they were on the Lord's side and that the Lord was on their side. Being in the Lord's army, as many soldiers wrote,

made the conflict a war for the Lord and a war against His enemies. It gave the war the highest possible purpose, meaning,

and mission. It therefore encouraged innumerable soldiers to enlist in the army believing it was sanctioned directly from

the Almighty. General "Stonewall "Jackson even referred to the army in his command as the "Lord's Army." The American Civil

War has too many names to state, but the popular names are Brothers War, Brother Against Brother War, American Civil War,

U.S. Civil War, War of the Rebellion, War of Northern Aggression, and War of Southern Independence.

All slaves in the Confederacy were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, which stipulated that slaves in Confederate-held areas, but not in Border States

or in Washington, D.C., were free. Slaves in the Border States and Union-controlled areas in the South were freed by state

action or by the Thirteenth Amendment, although slavery effectively ended in the United States in the spring of 1865. The

full restoration of the Union was the work of a highly contentious postwar and aftermath era known as Reconstruction.

| American Civil War results |

|

| Civil War soldiers, known as Amputees, at Armory Square Hospital, Washington, D.C., 1860s |

More than 10,500 battles and skirmishes occurred during the Civil War, with 384 engagements (3.7

percent) identified as the principal battles and classified according to their historical significance. While the war produced

an estimated 1,030,000 casualties (3% of the U.S. population, which today would equate to nearly 9,000,000 souls), including

approximately 620,000 deaths (two-thirds by disease), Napoleonic Tactics were the contributing factors to the high casualties during the conflict.

Let's take a moment and think about it on today's terms. To put it into perspective,

3% of the U.S. population equates to the combined population of the present-day states of New Hampshire, Hawaii, Rhode Island,

Montana, Delaware, South Dakota, Alaska, North Dakota, Vermont and Wyoming. See also American Civil War History, Facts, and Statistics and Civil War Comparison of the North and South.

Civil War casualties were defined as soldiers who were unaccounted

for or unavailable for service. Casualties included killed in action, mortally wounded, wounded, missing, died of disease,

died as a prisoner-of-war, died of causes other than battle, captured, and deserted. On the other hand, fatalities only included

soldiers who were killed in action, mortally wounded, and died of disease or from other causes. Civil War statisticians

had a strict application of the words, killed, died, dead, and deaths. Furthermore, casualties included fatalities, while

fatalities did not include all casualties. Casualty has been, by many, erroneously interchanged with fatality. See also Total Civil

War killed and dead by category for each Union and Confederate state.

The primary cause of battle deaths and wounds

was from the firearm known as the small arm. Although one in four Civil War soldiers never returned home, one in thirteen

soldiers became an amputee. Even though amputation was the wounded soldier's best friend, one in four amputees died

principally as a result of gangrene. While gangrene was the number one cause of death for amputees, amputation was, nevertheless,

the wounded soldier's principal means of survival. Amputation had to be performed quickly, however, within 48 hours, to inhibit

blood poisoning, bone infection, or gangrene. A soldier who had his forearm amputated had a survival rate of 76%, while

amputation at the hip joint witnessed a survival rate of merely 12%. See also Comparison of Union and Confederate Weapons, Firearms, and Small Arms.

The war accounted for more casualties than all previous U.S. wars combined.

Presently, the causes of the war, the reasons for its outcome, and even the name of the war itself are subjects of lingering

controversy. The main result of the war was the restoration of the Union. Also, approximately 4 million slaves were freed

in 1865. Based on 1860 United States census figures, 8% of all white males aged 13 to 43 died in the war, including 6% in

the North and an extraordinary 18% in the South. See also: American

Civil War Battles, Casualties, & Statistics and Organization of Union and Confederate Armies.

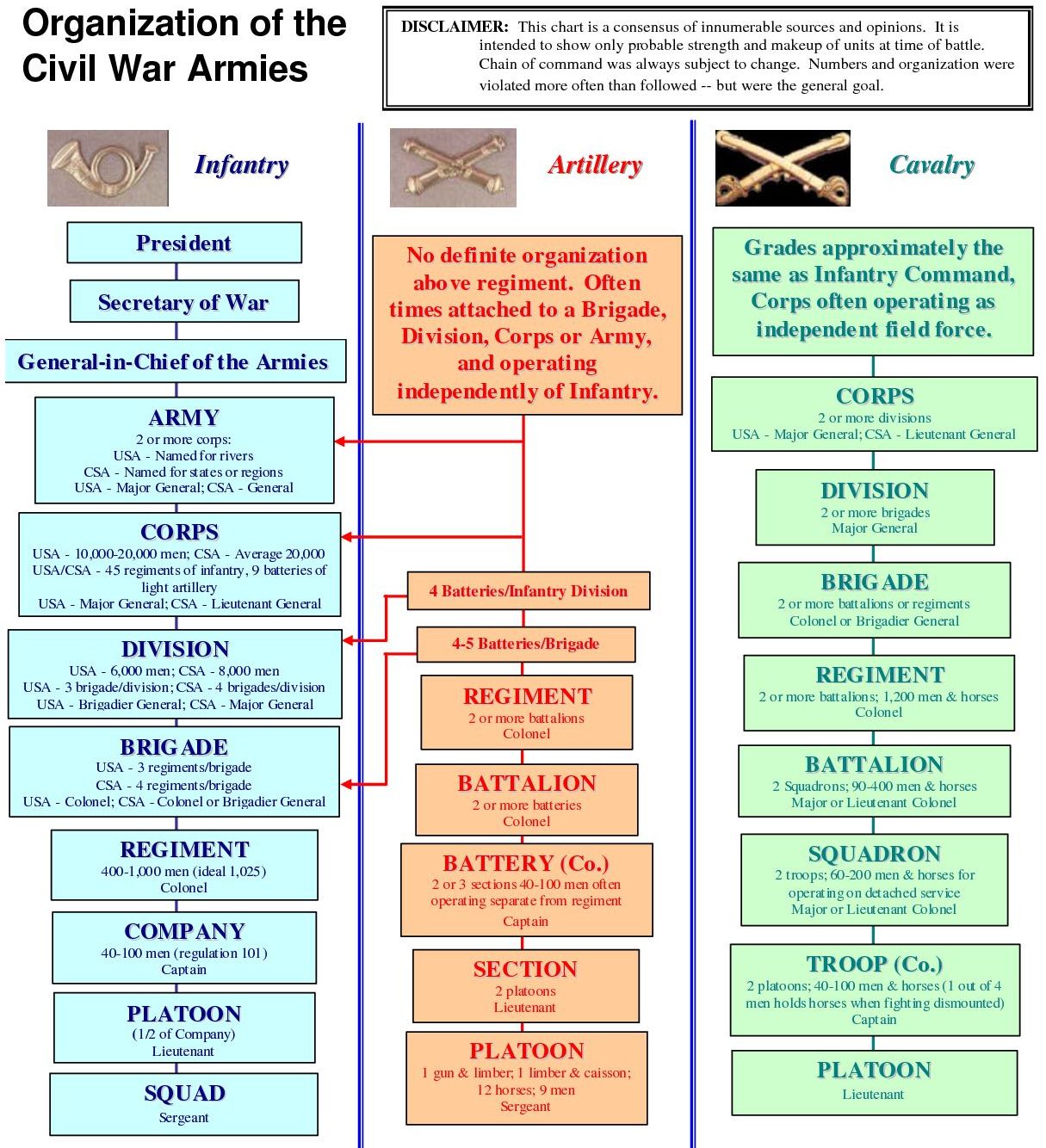

The Civil War military, for both the Union and Confederacy, evolved in many

aspects during the grueling four year struggle. While the Army organization consisted primarily of infantry,

artillery, and cavalry, infantry units totaled more than all other units combined. For every soldier that was killed and mortally

wounded in battle, two died as result of disease. As a result of the war, some Southern towns consisted only

of widows, children and the elderly, because all military aged men had died in the conflict. See also The Civil War Soldier: Homepage.

Numerous inventions and innovations were a result of the Civil War.

The arts of tactics and strategy were revolutionized by the many developments introduced during the 1860's. Thus the Civil

War ushered in a new era in warfare with the: FIRST practical machine gun, FIRST repeating rifle used in combat, FIRST use

of the railroads as a major means of transporting troops and supplies, FIRST mobile siege artillery mounted on rail cars,

FIRST extensive use of trenches and field fortifications, FIRST large-scale use of land mines, known as "subterranean shells",

FIRST naval mines or "torpedoes", FIRST ironclad ships engaged in combat, FIRST multi-manned submarine, FIRST organized and

systematic care of the wounded on the battlefield, FIRST widespread use of rails for hospital trains, FIRST organized military

signal service, FIRST visual signaling by flag and torch during combat, FIRST use of portable telegraph units on the battlefield;

FIRST military reconnaissance from a manned balloon, FIRST draft in the United States, FIRST organized use of Negro troops

in combat, FIRST voting in the field for a national election by servicemen, FIRST income tax—levied to finance the war,

FIRST photograph taken in combat, FIRST Medal of Honor awarded an American soldier. See also Civil War Comparison of the North

and South.

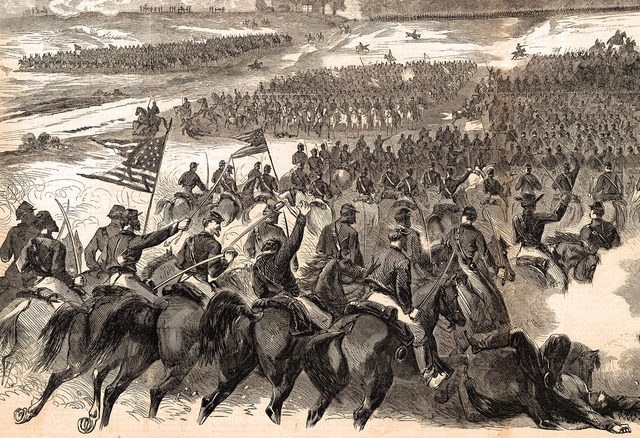

| Civil War military organization |

|

| Union and Confederate army of infantry, cavalry, and artillery |

(The Civil War Army Organization. The backbone of the Civil War army was

its infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The opposing organizations were similar because the bulk of the Northern and Southern

commanding generals were trained at West Point and studied the tactics of the era.)

Once the American Civil War (1861-1865) with the United States began,

the Confederacy pinned its hopes for survival on military intervention by Great Britain and France. The Confederates who had

believed that "cotton is king"—that is, Britain had to support the Confederacy to obtain cotton—proved mistaken.

The British had stocks to last over a year and had been developing alternative sources of cotton, most notably India and Egypt.

They were not about to go to war with the U.S. to acquire more cotton at the risk of losing the large quantities of food imported

from the North. The Confederate government sent repeated delegations to Europe but historians give them low marks for their

poor diplomacy. James M. Mason went to London and John Slidell traveled to Paris. They were unofficially interviewed, but

neither secured official recognition for the Confederacy.

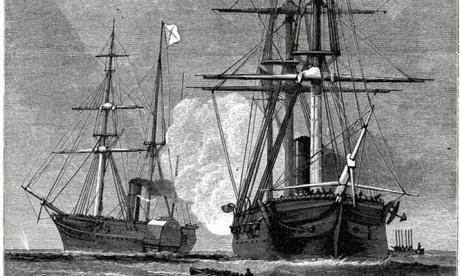

In late 1861 unlawful actions of the U.S. Navy in seizing a British ship,

in what was known as the Trent Affair, outraged Britain and placed both nations on the brink of war. Recognition of the Confederacy seemed at hand, but Lincoln

released the two detained Confederate diplomats, held discussions with British diplomats, and defused the volatile situation.

| Trent Affair |

|

| USS San Jacinto intercepts British mail packet RMS Trent |

Throughout the early years of the war, British foreign secretary Lord John

Russell, Emperor Napoleon III of France, and, to a lesser extent, British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, showed interest

in recognition of the Confederacy or at least mediation of the war. The Union victory at the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg)

and abolitionist opposition in Britain put an end to the plans. The cost to Britain of a war with the U.S. would have been

high: the immediate loss of American grain shipments, the end of exports to the U.S.,

the seizure of billions of pounds invested in American securities. War would have meant higher taxes, another invasion of

Canada, and full-scale worldwide attacks on the British merchant fleet.

(Right) While the San Jacinto, having overtaken the British mail packet

Trent, forces her to heave to, Confederate commissioners Mason and Slidell were subsequently detained.

While outright recognition would have meant certain war with the United

States, in the summer of 1862 fears of a race war, as had transpired in Haiti, led to the British considering intervention

for humanitarian reasons. Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation did not lead to interracial violence let alone a bloodbath,

but it did give the friends of the Union strong talking points in the arguments that raged across Britain.

John Slidell, emissary to France,

did succeed in negotiating a loan of $15,000,000 from French capitalists. The money was used to purchase ironclad warships,

as well as military supplies that arrived by blockade runners. The British government

allowed blockade runners to be built in Britain and operated by British seamen. Several European nations maintained diplomats

in place who had been appointed to the U.S., but no nation appointed any diplomat to the Confederacy. However, those nations

did recognize the Union and Confederate sides as belligerents.

In 1863, the Confederacy expelled the European diplomatic missions for advising

their resident subjects to refuse to serve in the Confederate army. Both Confederate and Union agents were allowed to work

openly in British territories. Some state governments in northern Mexico negotiated local agreements to cover trade on the

Texas border. Pope Pius IX wrote a letter to Jefferson Davis in which he addressed Davis as the "Honorable President of the

Confederate States of America." The Confederacy appointed Ambrose Dudley Mann as special agent to the Holy See on September

24, 1863. But the Holy See never released a formal statement supporting or recognizing the Confederacy.

The Confederacy was seen internationally as a serious attempt at nationhood,

and European governments sent military observers, both official and unofficial, to assess the de facto establishment of independence.

These included: Arthur Freemantle of the British Coldstream Guards, Fitzgerald Ross of the Austrian Hussars, and Justus Scheibert

of the Prussian army. European travelers visited and wrote accounts for publication. Importantly in 1862, the Frenchman Charles

Girard's Seven months in the rebel states during the North American War testified "this government ... is no longer a trial

government ... but really a normal government, the expression of popular will".

Due in part to Lincoln's covert support of Mexican President Benito Juarez,

by late spring of 1863 France was in need of Confederate cotton and other Caribbean commerce to sustain the French conquest

of Mexico, an effort to reestablish France's North American empire. News of Lee's decisive victory at Chancellorsville had

reached Europe, and French Emperor Napoleon III assured Confederate diplomat John Slidell that he would make "direct proposition"

to the United Kingdom for joint recognition. The Emperor made the same assurance to Members of Parliament John A. Roebuck

and John A. Lindsay. Roebuck in turn publicly prepared a bill to submit to Parliament, June 30, supporting joint Anglo-French

recognition of the Confederacy. Preparations for Lee's incursion into Pennsylvania were underway to influence the midterm

U.S. elections. Confederate independence and nationhood was at a turning point. "Southerners had a right to be optimistic,

or at least hopeful, that their revolution would prevail, or at least endure".

By December 1864, Davis considered sacrificing slavery in order to enlist

recognition and aid from Paris and London; he secretly sent Duncan F. Kenner to Europe with a message that the war was fought

solely for "the vindication of our rights to self-government and independence" and that "no sacrifice is too great, save that

of honor." The message stated that if the French or British governments made their recognition conditional on anything at

all, the Confederacy would consent to such terms. Davis's message could not explicitly

acknowledge that slavery was on the bargaining table due to still-strong domestic support for slavery among the wealthy and

politically influential. Although Louis-Napoleon responded receptively to the message in March 1865, he would not commit without

the cooperation of Great Britain. Lord Palmerston, however, withheld support, as the war had turned against the Confederacy

and Britain wouldn't side with a lost cause. See also American Civil War and International Diplomacy.

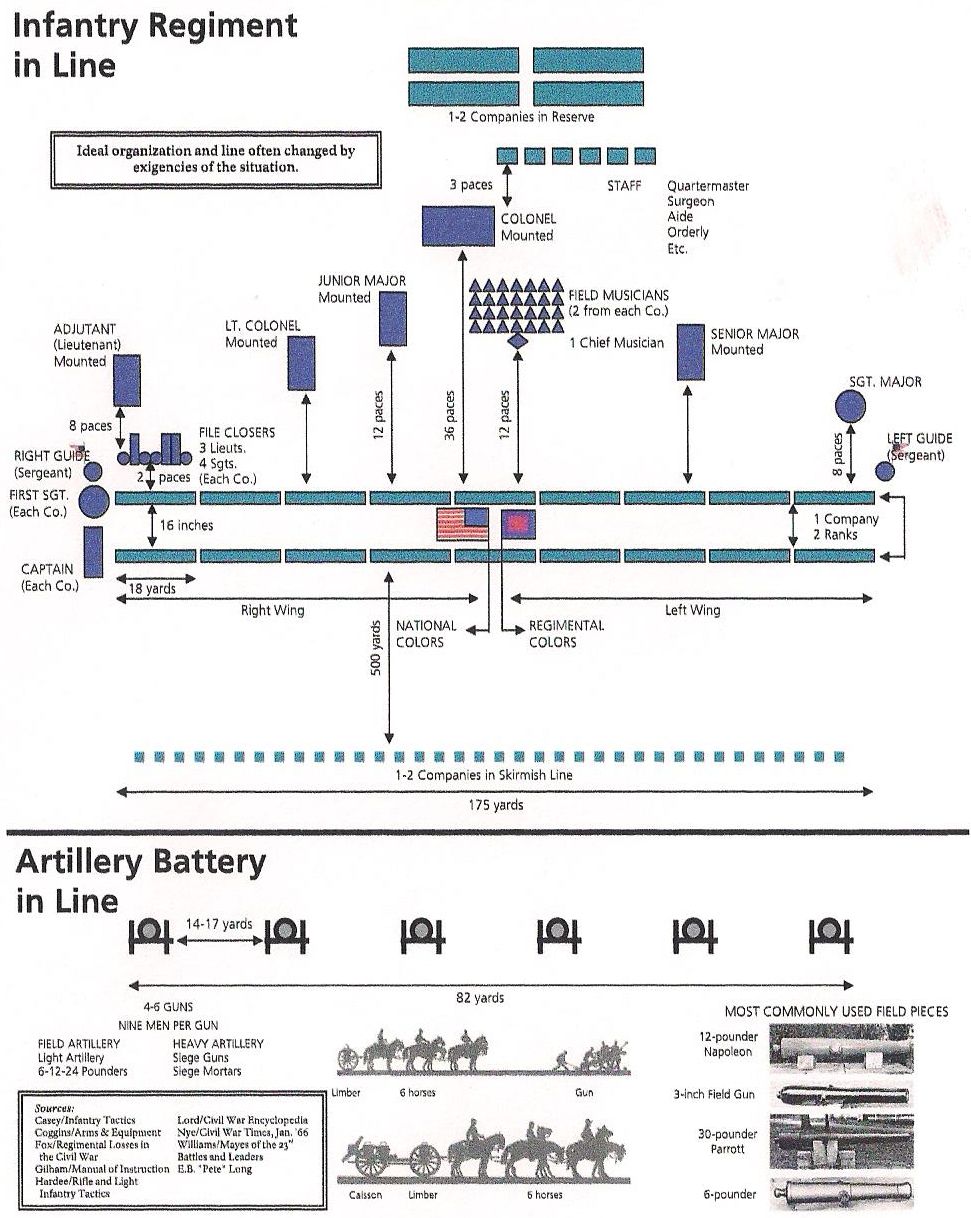

| Civil War army organization |

|

| Union and Confederate armies and formations |

(About) Civil War Infantry Line. The ideal line is presented, but it often

changed according to the exigencies of battle. Because the battle resembled a chess match while opposing commanding generals

issued orders and commands throughout the fight, it was no surprise that, during their spare time, officers were rather

fond of chess.

The Union Army was the military force that fought during the American Civil War. It consisted

of the small United States Army (the regular army), augmented by massive numbers of units supplied by the Northern states,

composed of volunteers as well as conscripts. The Union Army fought and eventually defeated the smaller Confederate States

Army, but at a great cost. Approximately 360,000 died from all causes and an additional 280,000 were wounded.

The Confederate Army was the military backbone of the Confederate States

of America, also known as the "Confederacy." On February 28, 1861, the Provisional Confederate Congress established a provisional

volunteer army and gave control over military operations and authority for mustering state forces and volunteers to the President

of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, a graduate of the United States Military Academy and colonel of a volunteer regiment

during the Mexican-American War.

On early March 1861, the Provisional Confederate Congress passed additional

military legislation and established a more permanent army. An accurate count of the number of individuals who served

in the C.S. Army is impossible due to incomplete and destroyed Confederate records. The better estimates of the total number

of soldiers were between 750,000 and 1,000,000 men. This does not include an unknown number of slaves who were impressed into

performing various tasks for the army, such as construction of fortifications and defenses or driving wagons. Since these

figures include estimates of the total number of individual soldiers who served at any time during the war, they do not represent

the size of the army in the field at any given date. These numbers also do not include men who served in the Confederate navy.

Although most Civil War soldiers were volunteers, both sides ultimately

resorted to conscription, aka the draft. In the absence of exact records, estimates of the percentage of Confederate soldiers

who were draftees are about double the 6 per cent of Union soldiers who were conscripts. Some historians have suggested that

the threat of conscription may have had a greater effect on raising volunteers than it did in providing large numbers of reliable

soldiers.

Confederate casualty figures also are incomplete and unreliable. The best

estimates of the number of deaths of Confederate soldiers are approximately 94,000 killed or mortally wounded in battle, 164,000

deaths from disease, and between 26,000 and 31,000 deaths in Union prison camps. One estimate of Confederate wounded, which

is considered incomplete, is 194,026. These numbers do not include men who died from other causes other than battle, which

would add several thousand to the death toll.

The main Confederate armies, the Army of Northern Virginia under General

Robert E. Lee and the remnants of the Army of Tennessee and various other units under General Joseph E. Johnston, surrendered

in April 1865. Other Confederate forces surrendered between April and June 1865. The Confederacy's government was

effectively dissolved with the last meeting of the Confederate cabinet on May 5, 1865, and with the capture of President Jefferson

Davis by Union forces on May 10, 1865.

|

|

|

|

|

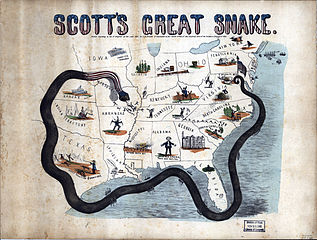

| Civil War military strategy |

|

| Union Anaconda Plan |

The Civil War promoted many innovations in military strategy.

W. J. Hardee published the first revised infantry tactics for use with modern rifles in 1855. However, even these tactics

proved ineffective in combat, as it involved massed volley fire, in which entire units (primarily regiments) would fire simultaneously. These tactics had not been tested before in actual combat, and the commanders of these units would post their soldiers at incredibly close

range, opposite the rifled musket, which led to disastrous mortality rates. In a sense, the weapons had evolved beyond

the tactics, which would soon change as the war drew to a close. While railroads provided the first mass movement of troops,

the telegraph was used by both sides, which enabled political and senior military leaders to transmit and receive reports

from commanders in the field.

In previous wars, when armies applied Napoleonic

Tactics with smoothbore muskets, the soldiers would mass to within 100 yards of the defensive lines, the maximum effective

range of the smoothbore. Attackers would have to endure one volley of inaccurate smoothbore musket fire before they could

close with the defenders. But by the civil War, the smoothbores had been replaced with rifled muskets, using the quick loadable

miniť ball, with accurate ranges up to 900 yards. Now the soldiers were subjected to three or four aimed volleys while

enduring the outdated Napoleonic Tactics.

The dominate Confederate philosophy evolved into a combination of "dispersal

with a defensive concentration around Richmond," its capitol. The Davis administration considered the war purely defensive,

a "simple demand that the people of the United States would cease to war upon us."

As the Confederate government lost control of territory in campaign after

campaign, it was said that "the vast size of the Confederacy would make its conquest impossible". The enemy would be struck

down by the same elements which so often debilitated or destroyed visitors and transplants in the South. Heat exhaustion,

sunstroke, endemic diseases such as malaria and typhoid would match the destructive effectiveness of the Moscow winter on

the invading armies of Napoleon.

But despite the Confederacy's essentially defensive stance, in the early

stages of the war there were offensive visions of seizing the Rocky Mountains or cutting the North in two by marching to Lake

Erie. Then, at a time when both sides believed that one great battle would decide the conflict, the Confederate won a great

victory at the First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas (the name used by the South). It drove the Confederate

people "insane with joy", the public demanded a forward movement to capture Washington DC, relocate the Capital there, and

admit Maryland to the Confederacy. A council of war by the victorious Confederate generals decided not to advance against

larger numbers of fresh Federal troops in defensive positions. Davis did not countermand it.

Following the Confederate incursion halted at the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg)

in September 1862, generals proposed concentrating forces from state commands to re-invade the north. Nothing came of

it. Again in early 1863 at his incursion into Pennsylvania, Lee requested of Davis that Beauregard simultaneously attack Washington

with troops taken from the Carolinas. But the troops there remained in place during the Gettysburg Campaign.

While the eleven states of the Confederacy were outnumbered by the North

about four to one in military manpower, it was overmatched far more in military equipment, ability to produce and procure

it, railroads for transport, and wagons supplying the front. Big guns were out-ranged and small arms were less effective.

Confederate military policy innovated to compensate. Booby-trapped land

mines were laid in the path of invading armies. Harbors, inlets and inland waterways were laced with numbers of sunken "torpedo"

mines and covered with mobile artillery batteries. Rangers and partisans were sent to disrupt and destroy supplies of

invading armies until they were disbanded.

The Confederacy relied on external sources for war materials. The first

came from trade with the enemy. "Vast amounts of war supplies" came through Kentucky, and thereafter, western armies were

"to a very considerable extent" provisioned with illicit trade via Federal agents and Northern private traders. But that trade

was interrupted in the first year of war by Admiral Porter's river gunboats as they gained dominance along navigable rivers

north–south and east–west. Overseas blockade running then came to be of "outstanding importance". On April 17,

President Davis called on privateer raiders, the "militia of the sea", to make war on U.S. seaborne commerce. Despite noteworthy

effort, over the course of the war the Confederacy was found unable to match the Union in ships and seamanship, materials

and marine construction.

Perhaps the most implacable obstacle to success in the 19th century warfare

of mass armies was the Confederacy's lack of manpower and sufficient numbers of disciplined, equipped troops in the field.

During the wintering of 1862–1863, Lee observed that none of his famous victories had resulted in the destruction of

the opposing army. He lacked reserve troops to exploit an advantage on the battlefield as Napoleon had done. Lee explained,

"More than once have most promising opportunities been lost for want of men to take advantage of them, and victory itself

had been made to put on the appearance of defeat, because our diminished and exhausted troops have been unable to renew a

successful struggle against fresh numbers of the enemy."

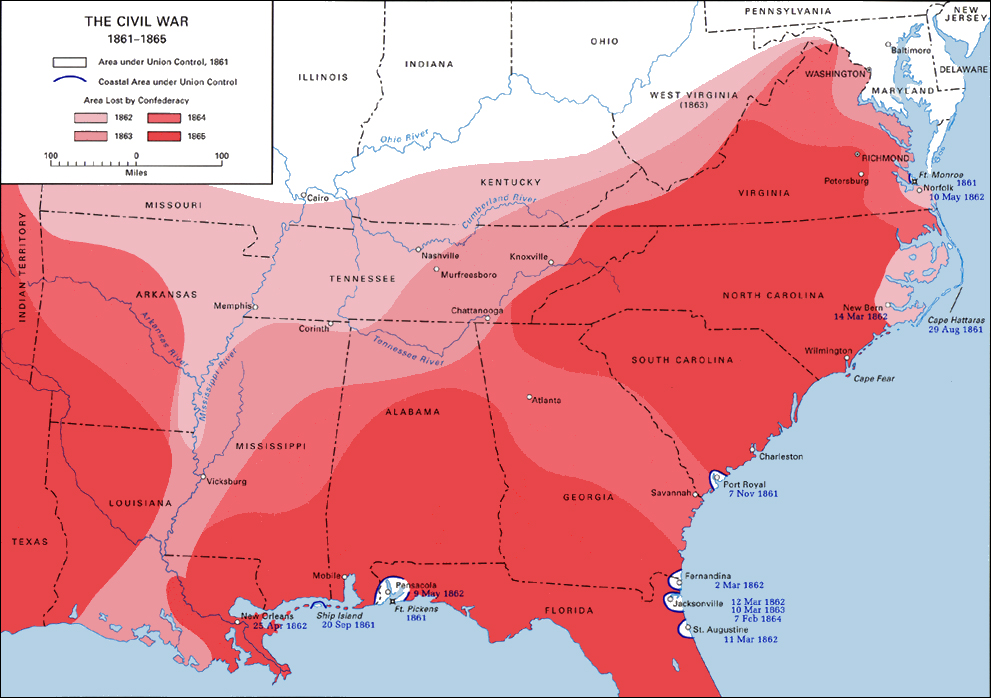

| Civil War military strategy |

|

| Confederate territory lost by year |

The Civil War was a contest marked by the ferocity and frequency of battle.

Over four years, hundreds of named battles were fought, as well as innumerable minor actions and skirmishes. In the scales

of world military history, both sides fighting were characterized by their bitter intensity and high casualties. "The American

Civil War was to prove one of the most ferocious wars ever fought". Without geographic objectives, the only target for each

side was the opposing soldier.

The small Union Navy of 1861 was rapidly enlarged to 6,000 officers and

45,000 men in 1865, with 671 vessels, having a tonnage of 510,396. Its mission was to blockade Confederate ports, take control

of the river system, defend against Confederate raiders on the high seas, and be ready for a possible war with the British

Navy. Meanwhile, the main riverine war was fought in the West, where a series of major rivers gave access to the Confederate

heartland. In the "East, the Navy supplied and moved army forces to and fro, and occasionally shelled Confederate installations."

By early 1861, General Winfield Scott had devised the Anaconda Plan

to win the war with as little bloodshed as possible. Scott argued that a Union blockade of the main ports would weaken the Confederate economy. Lincoln adopted parts of the plan, but he overruled Scott's caution

about 90-day volunteers. Public opinion however demanded an immediate attack by the army to capture Richmond.

In April 1861, Lincoln announced the Union blockade of all Southern ports;

commercial ships could not get insurance and regular traffic ended. The South blundered in embargoing cotton exports in 1861

before the blockade was effective; by the time they realized the mistake it was too late. "King Cotton" was dead, as the South

could export less than 10% of its cotton. The blockade shut down the ten Confederate seaports with railheads that moved almost

all the cotton, especially New Orleans, Mobile, and Charleston. By June 1861, warships were stationed off the principal Southern

ports, and a year later nearly 300 ships were in service.

British investors built small, very fast, steam-driven blockade runners

that traded arms and luxuries delivered from Britain through Bermuda, Cuba, and the Bahamas in return for high-priced cotton.

The ships were so small that only a small amount of cotton was ever transported. When the Union Navy seized any blockade runner,

the ship and cargo were condemned as a Prize of war and sold with the proceeds given to the Navy sailors; the captured crewmen

were mostly British and they were simply released.

The Southern economy nearly collapsed during the war. There were multiple

reasons for this: the severe deterioration of food supplies, especially in cities, the failure of Southern railroads, the

loss of control of the main rivers, foraging by Northern armies, and the seizure of animals and crops by Confederate armies.

Historians agree that the blockade was a major factor in ruining the Confederate

economy. However, some argue that they provided just enough of a lifeline to allow Lee to continue fighting for additional

months, thanks to fresh supplies of 400,000 rifles, lead, blankets, and boots that the homefront economy could no longer supply.

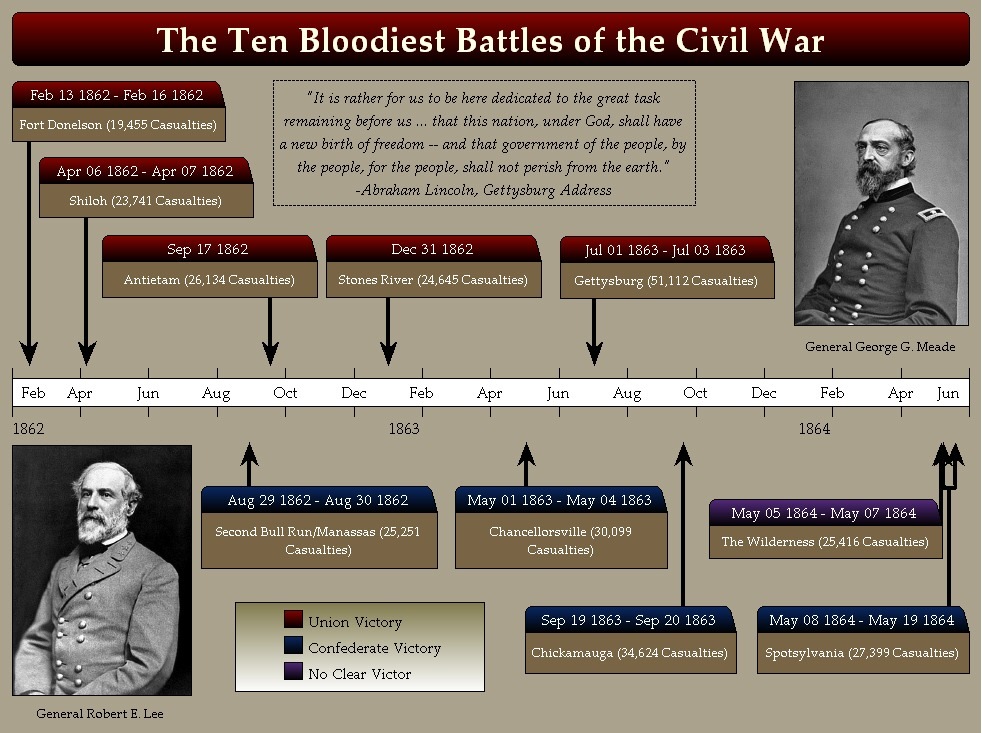

| American Civil War Battles and Casualties |

|

| Ten Civil War Battles with Most Casualties |

Anaconda Plan during 1863–1864

Although the failed Middle Tennessee campaign ended on January 2, 1863,

at the inconclusive Battle of Stones River, (Murfreesboro), both sides had suffered the largest percentage of casualties during

the war. The campaign was followed by another strategic withdrawal by Confederate forces. The Confederacy, however, won

a significant victory April 1863, repulsing the Federal advance on Richmond at Chancellorsville, causing the Union to withdrawal

and consolidate its positions along the Virginia coast and the Chesapeake Bay.

Without an effective answer to Federal gunboats, river transport and

supply, the Confederacy lost the Mississippi River following the capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Port Hudson in July

1863, ending Southern access to the trans-Mississippi West. July brought short-lived counters, Morgan's Raid into Ohio and

the New York City draft riots. Robert E. Lee's strike into Pennsylvania was repulsed at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, despite

Pickett's famous charge and other acts of valor. Southern newspapers assessed the campaign as "The Confederates did not gain

a victory, neither did the enemy."

September and November left Confederates yielding Chattanooga, Tennessee,

the gateway to the lower south. For the remainder of the war fighting was restricted inside the South, resulting in a slow

but continuous loss of territory. In early 1864, the Confederacy still controlled 53% of its population, but it withdrew further

to reestablish defensive positions. Union offensives continued with Sherman's March to the Sea to take Savannah and Grant's

Wilderness Campaign to encircle Richmond and besiege Lee's army at Petersburg.

In April 1863, the C.S. Congress had authorized a uniformed Volunteer Navy,

many of whom were British. Wilmington and Charleston had more shipping while "blockaded" than before the beginning of hostilities.

The Confederacy had altogether eighteen commerce destroying cruisers, which seriously disrupted Federal commerce at sea and

increased shipping insurance rates 900 percent. Commodore Tattnall unsuccessfully attempted to break the Union blockade on

the Savannah River in Georgia, with an ironclad in 1863. However, beginning in April 1864, the ironclad CSS Albemarle

engaged and unleashed havoc on Union gunboats for six months on the Roanoke River, N.C. The Federals closed Mobile Bay

by sea-based amphibious assault in August, ending Gulf coast trade east of the Mississippi River. In December, 1864, the

Battle of Nashville ended Confederate operations in the western theater.

The first three months of 1865 witnessed the Federal Campaign of the Carolinas,

devastating a wide swath of the remaining Confederate heartland. The "breadbasket of the Confederacy" in the Great Valley

of Virginia was occupied by Philip Sheridan. The Union Blockade captured Fort Fisher N,C,, and Sherman finally took Charleston,

S.C., by land.

The Confederacy controlled no ports, harbors or navigable rivers. Railroads

were captured or had ceased operating. Its major food producing regions had been war-ravaged or occupied. Its administration

survived in only three pockets of territory holding one-third its population. Its armies were defeated or disbanding. At the

February 1865 Hampton Roads Conference with Lincoln, senior Confederate officials rejected his invitation to restore the Union

with compensation for emancipated slaves. The Davis policy was independence or nothing, while Lee's army was devastated by

disease and desertion, barely holding the trenches defending Jefferson Davis' capital.

The Confederacy's last remaining blockade-running port, Wilmington, North

Carolina, was lost. When the Union forces broke through Lee's lines at Petersburg, Richmond fell immediately. Lee surrendered

the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865. "The

Surrender" marked the end of the Confederacy. Some Rebel officials escaped to Europe, but President Davis was captured

May 10; all remaining Confederate forces surrendered by June 1865. The U.S. Army took control of the Confederate areas without

post-surrender insurgency or guerrilla warfare against them, but peace was subsequently marred by a great deal of local violence,

feuding and revenge killings.

| Military casualties were 2% of the US population |

|

| Civil War military service claimed 620,000 soldiers |

(Above) Mathew B. Brady (ca. 1822 – January 15, 1896) was the

most celebrated 19th century American photographer, best known for his portraits of celebrities and his documentation of the

American Civil War. Because Brady was the first to employ photography on the battlefield, a Union politician, during

the Civil War, stated that Brady "stung the heart of every American with his images of war." And because of the graphic

images, coupled with a war with no end in sight, many Northern politicians feared for their political careers and even believed

and stated publicly that Brady and his associates were "worse than spies." As a result of angry politicians and Union

generals who threatened the press for allegedly writing reports, accompanied with Brady's photos, that showed "sympathy for

the enemy," in concert with a nation that desired to put the carnage of war behind them (including all reminders

of the conflict), the majority of the photographs taken during the Civil War (that managed to survive), were

not circulated until ca. 1905, or nearly 40 years after the conflict. Brady, however, is credited with being

the father of photojournalism and his name is synonymous with Civil War photography. The majority of Civil War era

photographs were either taken by Brady or someone in his employment. While researching the Civil War in pictures, e.g., Library

of Congress, National Park Service, National Archives, Smithsonian Institution, the researcher is quick to view the name Mathew

Brady on practically every photo.

| Consequences of Civil War |

|

| Civil War prisoner of war |

Of the 2,213,363 men who served in the Union Army during the Civil War,

364,511 died in combat, or from wounds in battle, disease, or other causes, and 281,881 were wounded. More than 1 out

of every 4 Union soldiers was killed or wounded during the war; casualties in the Confederate Army were even worse—1

in 3 Southern soldiers had been killed or wounded. It should be noted, however, that the Confederates suffered a

considerably lower amount of overall casualties than the Union, at roughly 260,000 total casualties to the Union's 360,000.

This is by far the highest casualty ratio of any war in which America has been involved.

In total, 620,000 soldiers died during the Civil War, which equaled 2%

of the total U.S. population. In today's terms, this would be the equivalent of 6 million American men being killed in

a single war.

By the end of the war deterioration of the Southern infrastructure was widespread.

The number of civilian deaths is unknown. Most of the war was fought in Virginia and Tennessee, but every Southern state was

affected as well as Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Indian Territory. Texas and Florida saw the least military

action. While much of the damage was caused by military action, most was caused by lack of repairs and upkeep, lack of resources,

and lack of men to maintain the Southern infrastructure.

The South's agriculture was not highly mechanized. The value of farm implements

and machinery in the 1860 Census was $81 million; by 1870, there was 40% less, worth just $48 million. Many old tools had

broken through heavy use; new tools were rarely available; even repairs were difficult.

The economic losses affected everyone. Banks and insurance companies were

mostly bankrupt. Confederate currency and bonds were worthless. The billions of dollars invested in slaves vanished. However,

most debts were left behind. Most farms were intact but most had lost their horses, mules and cattle; fences and barns were

in disrepair. The loss of infrastructure and productive capacity meant that rural widows throughout the region faced not only

the absence of able-bodied men, but a depleted stock of material resources that they could manage and operate themselves.

During four years of warfare, disruption, and blockades, the South used up about half its capital stock. The North, by contrast,

absorbed its material losses so effortlessly that it appeared richer at the end of the war than at the beginning.

The rebuilding would take years and was hindered by the low price of cotton

after the war. Outside investment was essential, especially in railroads. One of the greatest calamities which confronted

Southerners was the havoc wrought on the transportation system. Roads were impassable or nonexistent, and bridges were destroyed

or washed away. The important river traffic was at a standstill: levees were broken, channels were blocked, the few steamboats

which had not been captured or destroyed were in a state of disrepair, wharves had decayed or were missing, and trained personnel

were dead or dispersed. Horses, mules, oxen, carriages, wagons, and carts had nearly all fallen prey at one time or another

to the contending armies. The railroads were paralyzed, with most of the companies bankrupt. These lines had been the special

target of the enemy. On one stretch of 114 miles in Alabama, every bridge and trestle was destroyed, cross-ties rotten, buildings

burned, water-tanks gone, ditches filled up, and tracks covered in weeds and bushes ...

Communication centers like Columbia and Atlanta were in ruins; shops and

foundries were wrecked or in disrepair. Even those areas bypassed by battle had been

pirated for equipment needed on the battlefront, and the wear and tear of wartime usage without adequate repairs or replacements

reduced all to a state of disintegration.

In the following century, however, the United States would evolve into the

world's superpower and even be considered the most prosperous nation on the planet.

Analysis

The Civil War

caused 620,000 killed, and it forced the United States military to reexamine its stiff, outdated tactics and strategies

that had led to the carnage. The U.S. Military Academy, U.S. Naval Academy, and other military schools would

adapt, improvise, and overcome to meet the present and future challenges of war. After all, numerous inventions and innovations

were a result of the Civil War. The arts of tactics and strategy were revolutionized by the many developments introduced

during the 1860s. Thus the Civil War ushered in a new era in warfare with the: FIRST practical machine gun, FIRST repeating

rifle used in combat, FIRST use of the railroads as a major means of transporting troops and supplies, FIRST mobile siege

artillery mounted on rail cars, FIRST extensive use of trenches and field fortifications, FIRST large-scale use of land mines,

known as "subterranean shells", FIRST naval mines or "torpedoes", FIRST ironclad ships engaged in combat, FIRST multi-manned

submarine, FIRST organized and systematic care of the wounded on the battlefield, FIRST widespread use of rails for hospital trains, FIRST organized military signal service, FIRST visual signaling by flag

and torch during combat, FIRST use of portable telegraph units on the battlefield; FIRST military reconnaissance from a manned

balloon, FIRST draft in the United States, FIRST organized use of Negro troops in combat, FIRST voting in the field for a

national election by servicemen, FIRST income tax—levied to finance the war, FIRST photograph taken in combat, FIRST

Medal of Honor awarded an American soldier. See also Civil War Comparison of

the North and South.

Sources: Library of Congress; National Archives; National Park Service;

Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union. Vol. 1, The Improvised War 1861–1862. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1959.

ISBN 0-684-10426-1; Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union. Vol. 2, War Becomes Revolution 1862–1863. New York: Charles

Scribner's Sons, 1960. ISBN 1-56852-297-5; Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union. Vol. 3, The Organized War 1863–1864.

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971. ISBN 0-684-10428-8; Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union. Vol. 4, The Organized War

to Victory 1864–1865. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971. ISBN 1-56852-299-1; Shannon, Fred A. The Organization

and Administration of the Union Army 1861–1865. 2 vols. Gloucester, MA: P. Smith, 1965. OCLC 428886. First published

1928 by A.H. Clark Co.; Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern

Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-36453-1; Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865

Organization and Operations. Vol. 2, The Western Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-253-36454-X;

Anderson, Bern, By Sea and By River: The Naval History of the Civil War. Knopf, 1962. Reprint, Da Capo, 1989, ISBN 0-306-80367-4;

Browning, Robert M. Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. University

of Alabama Press, 1993, ISBN 0-8173-5019-5; Browning, Robert M. Jr., Success is All That Was Expected: The South Atlantic

Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. Brassey’s, Inc., 2002, ISBN 1-57488-514-6; Dufour, Charles L., The Night the

War Was Lost. University of Nebraska Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8032-6599-9; Gibbon, Tony, Warships and Naval Battles of the Civil

War. Gallery Books, 1989, ISBN 0-8317-9301-5; Musicant, Ivan, Divided Waters: The Naval History of the Civil War. HarperCollins,

1995, ISBN 0-06-016482-4; Soley, James Russell, The Blockade and the Cruisers. C. Scribner’s Sons, 1883; Reprint Edition,

Blue and Grey Press; Tucker, Spencer, Blue and Gray Navies: The Civil War Afloat. Naval Institute Press, 2006, ISBN 1-59114-882-0;

Wise, Stephen R., Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War, University of South Carolina Press,

1988, ISBN 0-87249-554-X; Basler, Roy P., ed., The Collected Works of Abraham

Lincoln, Rutgers University Press, 1953, ISBN 978-0-8135-0172-7; Confederate States. War Dept (1863). Regulations for the

Army of the Confederate States. Richmond: J.W. Randolph; Crute, Joseph H. Jr. (1987). Units of the Confederate States Army.

2nd ed. Gaithersburg: Olde Soldier Books. ISBN 0-942211-53-7; Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. The Civil War Dictionary. New York:

McKay, 1959; revised 1988. ISBN 978-0-8129-1726-0; Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford

University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1; Evans, Clement A., Confederate Military History; Volume III – Virginia

by Maj. Jedediah Hotchkiss. The National Historical Society, 2008, facsimile reprint, originally printed in Atlanta, by Confederate

Publishing Company, 1899; Henderson, G. F. R., Stonewall Jackson and the American Civil War, Smithmark reprint, 1995, ISBN

978-0-8317-3288-2; Johnson, Clint, The Politically Incorrect Guide to The South. Washington, D.C., Regnery Publishing, Inc.,

2006, ISBN 1-59698-500-3; Johnston, David E., The Story of a Confederate Boy in the Civil War (Serving in the 7th Virginia

Infantry Regiment). ISBN 978-1-84685-666-2; Johnston II, Angus James, Virginia Railroads in the Civil War, University of North

Carolina Press for the Virginia Historical Society, 1961; Levine, Bruce, Confederate

Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves during the Civil War, Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-19-514762-9;

Long, E. B. The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971. OCLC 68283123; Robson,

John S., How A One-Legged Rebel Lives: Reminiscences of the Civil War; The Story of the Campaigns of Stonewall Jackson, Kessinger

Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84685-665-5; U.S. War Department, The War

of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, U.S. Government Printing Office,

1880–1901; Price, William H. The Civil War Centennial Handbook; National Museum of Health and Medicine; U.S. National

Library of Medicine.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|