|

When did the Civil War End?

What was the Date and Location that the Civil War Ended?

When and Where did the Civil War End?

Last Battle and Final Surrender of the Confederate

Army

Introduction

When

General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to General U.S. Grant, President Jefferson Davis was determined to continue the

fight, but Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, the highest ranking U.S. official to ever commit treason, said that "this has

been a magnificent epic, in God's name let it not terminate in farce."

When did the American Civil War end? A question that is phrased

many ways and is asked from casual students to diehard Civil War buffs. The conflict that claimed some 620,000

Americans, the deadliest war in the nation's history, actually did not have a single date that hostilities ceased, but

rather it consisted of an order of Confederate forces surrendering to U.S. authorities.

When Lee surrendered to Grant

at Appomattox

he only surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia, one army, albeit the most significant in the field, while numerous other

Confederate armies continued to remain active. Confederate President Jefferson Davis, as well as his inner circle, also

refused to surrender. Lee's acquiescence signaled the beginning of the end of what many called the Lost Cause, and it would

soon be followed by the capitulation of other prominent generals and their commands.

The Confederacy itself could not

surrender, however, because, by now, Richmond, the Southern capitol, had

fallen, the government officials had fled, and many of the papers and documents of the newly formed Confederate States of

America had been burned. It was now in the hands of each Rebel commander in the field to surrender his respective army

as news from the East reached him. Beginning with Lee, the following are brief descriptions of how each Confederate fighting

force surrendered during America’s

darkest hour.

| Last Civil War Surrender? |

|

| While Lee surrenders to Grant at Appomattox, the Civil War raged on... |

General Robert E. Lee on April 9, 1865

Having arranged a truce and sent

notes to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant requesting a meeting, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee awaited his response. Shortly after noon, April 9,

1865,

Grant’s reply arrived and Lee rode into the village of Appomattox to prepare for Grant’s arrival. Lee’s aide selected the home of Wilmer Mclean.

Lee waited in the parlor. At about 1:30 p.m. Grant arrived with his staff. The two generals exchanged greetings

and small talk, and then Lee declared the purpose of the meeting. Grant stated, in writing, the surrender terms in an order

book and handed it to Lee to read. The terms, proposed in an exchange of notes the previous day, were honorable: Surrendered

officers and their troops were to be paroled and prohibited from taking up arms until properly exchanged, and arms and supplies

were to be given over as captured property. After Lee had read the terms and added an omitted word, he ordered his aide to

write a letter of acceptance. This concluded at about 3:45 p.m. when the generals exchanged

documents. Riding back to his lines, Lee was swarmed by his adoring troops from his beloved Army of Northern Virginia, many nearly hysterical with grief. Trying to soothe them with quiet phrases—you

have done all your duty. Leave the results to God, were some of the words from Lee, as he rode slowly on, followed by

many who wept and implored him to say that they should fight on. The next day he issued his eloquent farewell to his army.

On the morning of April 11, following a spartan breakfast and tearful good-byes from his staff, the general mounted his warhorse,

Traveler, and with a Union honor guard left Appomattox for

home.

General Joseph E. Johnston on April 26,

1865

Following its strategic defeat

at Bentonville,

N.C., March 21, 1865, the Confederate army of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston was reduced to perhaps 30,000 effectives, less than half the size of Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman's Federal command.

Though the Confederates had fought well at Bentonville, their leader had no illusions about stopping his adversary's inexorable

march through North Carolina. When Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield's

force, joining Sherman at Goldsboro, March 24, swelled the Union

ranks to 80,000, Johnston saw the end approaching. Dutifully,

however, he followed Sherman's resumed march northward April

10. En route the Confederate commander learned of the evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond and of Gen. Robert E. Lee's surrender at Appomattox.

This ended his long-held hope of joining Lee to oppose the invaders of the Carolinas. Arriving

near Raleigh, Johnston at first attempted to have North Carolina Gov. Zebulon B. Vance broach

surrender terms to Sherman. On April 12, Johnston went to Greensboro to meet with fugitive Confederate Pres. Jefferson Davis, whom

he persuaded to authorize a peace initiative. Sherman was

immediately receptive to peace negotiations, and on the 17th, under a flag of truce near Durham Station, met General Johnston

for the first time "although we had been interchanging shots constantly since May, 1863." The 2-day conference at the James

Bennett home produced peace terms acceptable to both generals. But since these intruded on matters of civil policy (for example,

recognition of the existing Southern state governments), officials in Washington quickly

rejected the agreement and criticized Sherman's imprudence.

Disappointed, the Federal leader informed Johnston that unless

more widely acceptable terms were reached, a 4-day armistice would end on April 26. That day, however,

the war-weary commanders met again at the Bennett home and thrashed out an agreement confined to military matters. At once

Gen-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant wired his approval, and, May 3, Johnston's once-proud army laid

down its arms, closing hostilities with the largest Confederate army east of the Mississippi River.

| Gen. Johnston surrenders to Gen. Sherman |

|

| General Sherman following his March through the Carolinas |

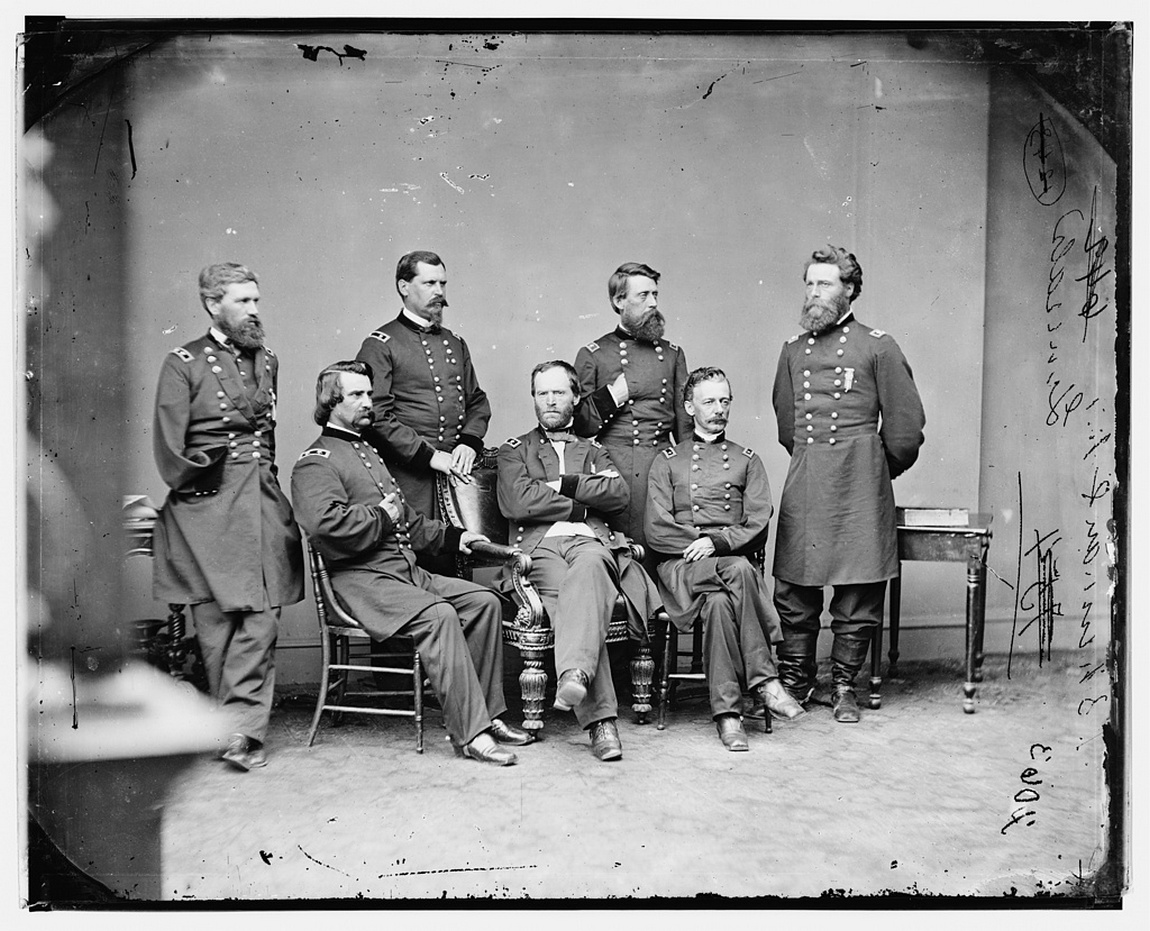

(About) General Sherman with Generals Howard, Logan,

Hazen, Davis, Slocum, and Mower, photographed by Mathew Brady, May 1865.

William Tecumseh Sherman (February 8, 1820 – February

14 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the United States Army during

the American Civil War (1861–65), receiving both recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy, and criticism

for the harshness of the "scorched earth" policies he implemented in conducting total war against the enemy. Military historian

Basil Liddell Hart famously declared that Sherman was "the first modern general."

Lieutenant General Richard Taylor on

May 4, 1865

At war’s end, Confederate

Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, son of former U.S. President Zachary Taylor, held command of the administrative entity called the Department of Alabama, Mississippi,

and East Louisiana, with some 12,000 troops. By the end of April 1865, Mobile,

AL., had fallen and news had reached Taylor

of the meetings between Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. Taylor agreed

to meet Maj. Gen. E.R.S. Canby for a conference a few miles north of Mobile.

On April 30 the two officers established a truce, terminable after 48 hours notice by either party, then partook of a

"bountiful luncheon ... with joyous poppings of champagne corks ... the first agreeable explosive sounds," Taylor wrote, "I had heard for years." A band played "Hail Columbia" and a few bars of "Dixie." The party separated: Canby went to Mobile and Taylor

to his headquarters at Meridian, Miss. Two days later Taylor received news of Johnston's surrender,

of Pres. Jefferson Davis's capture, and of Canby's insistence that the truce terminate. Taylor

elected to surrender, which he did on May 4, 1865, at Citronelle,

AL., some 40 miles north of Mobile.

"At the time, no doubts as to the propriety of my course entered my mind," Taylor

later asserted, "but such have since crept in." He grew to regret not having tried a last-ditch guerrilla struggle. Under

the terms, officers retained their sidearms, and mounted men their horses. All property and equipment was to be turned over

to the Federals, but receipts were issued. The men were paroled. Taylor

retained control of the railways and river steamers to transport the troops as near as possible to their homes. He stayed

with several staff officers at Meridian until the last man was gone, and then went to Mobile, joining Canby, who took Taylor by boat to the latter’s home

in New Orleans.

Captain Stephen Whitaker on May 12, 1865

On May 12, 1865, a Confederate force consisting of Highlanders and Indians would participate in "The Final Surrender" east of the Mississippi River. The soldiers of Company E, Walker's Battalion, Thomas' Legion of Indians and Highlanders, would

sign their parole papers beginning on May 12, with the last signature recorded on May 14, 1865. Col.

William H. Thomas, the legion's namesake, had

surrendered days earlier on May 9. Having recently

fought at Hanging Dog, in Cherokee County, Capt. Stephen Whitaker and Company E, First Battalion, were stationed at Franklin, North Carolina, but were moving toward White Sulphur Springs to reinforce Thomas when they were intercepted by the

Federals. Union

General Tillson had ordered Col. George W. Kirk and the Union 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry to Franklin (O.R., 1, Vol. 49, part II, p. 689), and when they approached

the battalion, Whitaker, having formed a skirmish line, was prepared for battle. But when he soon received word of Thomas and Martin capitulating

at nearby Waynesville, Whitaker and his company reluctantly laid down their arms and surrendered. Meanwhile,

on May 10, President Jefferson Davis was captured in Irwinville, GA. On May 14 the legionnaires completed their paroles and then

viewed "Whitaker roll them up, tie them, place them in a Haversack, and give them to Col. Kirk's Courier. And thus at

10 o'clock in the morning of May 14, 1865, our Civil War Soldier Life ended and our Every Day Working Life began," said John

H. Stewart of the Thomas Legion. With mixed emotions, the confederates had surrendered to Kirk understanding that the fight had finally come to an end, and the

reality of aftermath embraced the region.

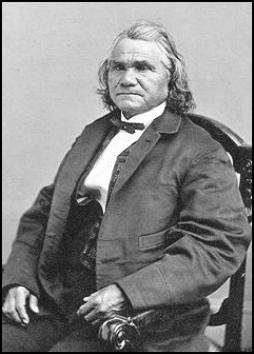

| Brig. Gen. Stand Watie |

|

| Cherokee Chief and Confederate General Stand Watie |

Lieutenant General E. Kirby Smith

on May 26, 1865

From 1862 until the conflict ended,

Confederate Lt. Gen. E. Kirby Smith commanded the Trans-Mississippi Department. By early May 1865 no significant Confederate

force remained east of the Mississippi River. Smith received official proposals that the surrender of his department

be negotiated. The Federals intimated that terms could be loose, but Smith’s demands were unrealistic. Smith then began

planning to continue the fight. Lt. Gen. U. S. Grant took preliminary steps to prepare a force to invade West

Texas should that prove necessary. It did not. The war’s last land fight occurred May 12-13, 1865, at

Palmito Ranch (aka Palmito Hill, Palmetto Ranch) Texas,

where 350 Confederates under Col. John S. "Rest in Peace" Ford scored a victory over 800 overconfident Federals under

Col. Theodore H. Barrett. But afterward the Confederates learned that Richmond

had fallen and Gen. Robert E. Lee had surrendered more than a month earlier. The news devastated their morale, and they abandoned

their lines. A similar decay in morale occurred throughout the department. On May 18, Smith left by stagecoach for Houston with plans to rally the remnants of the department. While he

traveled, the last of the department’s army dissolved, however. On May 26, at New Orleans, Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, acting in Smith’s name,

surrendered this department. Smith reached Houston on May

27 and learned that his army had evaporated. Not all of the Trans-Mississippi Confederates went home. Some 2,000 fled into

Mexico; most of them went alone or in

squad-sized groups, but one body numbered 300. With them, mounted on a mule, wearing a calico shirt and silk kerchief, sporting

a revolver strapped to his hip and a shotgun on his saddle, was Smith.

Brigadier General Stand Watie on June

23, 1865

When the leaders of the

Confederate Indians learned that the government in Richmond had fallen and the Eastern armies had

been surrendered, they, too, began making their plans to seek peace with the Federal government. The chiefs convened the Grand

Council June 15 and passed resolutions calling for Indian commanders to lay down their arms and for emissaries to approach

Federal authorities for peace terms. The largest force in Indian Territory was commanded

by Confederate Brig. Gen. Stand Watie (December 12, 1806 – September 9, 1871), who was also a chief

of the Cherokee Nation. Dedicated to the Confederate cause and unwilling to admit defeat, he kept his troops in the

field for nearly a month after Lt. Gen. E. Kirby Smith surrendered the Trans-Mississippi on May 26. Finally accepting the

futility of continued resistance, June 23, Watie rode into Doaksville near Fort Towson in Indian Territory and surrendered his battalion of Creek,

Seminole, Cherokee, and Osage Indians to Lt. Col. Asa C. Matthews, appointed a few weeks earlier to negotiate a “peace

with the Indians.” Watie was the last Confederate general officer to surrender his command.

Continued below...

Sources: Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War, edited by Patricia

L. Faust; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.

Recommended Viewing: The Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns. Review: The

Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns is the most successful public-television miniseries in American history. The 11-hour Civil War didn't just captivate a nation,

reteaching to us our history in narrative terms; it actually also invented a new film language taken from its creator. When

people describe documentaries using the "Ken Burns approach," its style is understood: voice-over narrators reading letters

and documents dramatically and stating the writer's name at their conclusion, fresh live footage of places juxtaposed with

still images (photographs, paintings, maps, prints), anecdotal interviews, and romantic musical scores taken from the era

he depicts. Continued below...

The Civil War uses all of these devices to evoke atmosphere and resurrect an event that many knew

only from stale history books. While Burns is a historian, a researcher, and a documentarian, he's above all a gifted storyteller,

and it's his narrative powers that give this chronicle its beauty, overwhelming emotion, and devastating horror. Using the

words of old letters, eloquently read by a variety of celebrities, the stories of historians like Shelby Foote and rare, stained

photos, Burns allows us not only to relearn and finally understand our history, but also to feel and experience it. "Hailed

as a film masterpiece and landmark in historical storytelling." "[S]hould be a requirement for every

student."

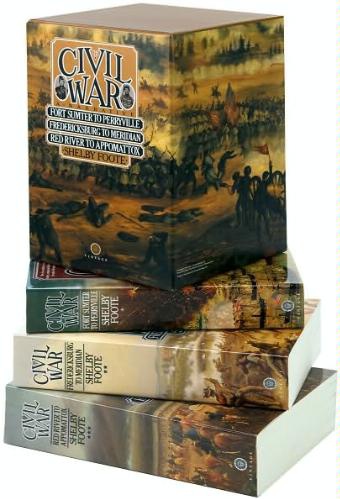

Recommended Reading: The Civil War: A Narrative,

by Shelby Foote (3 Volumes Set) [BOX SET] (2960 pages) (9.2 pounds). Review: This beautifully written trilogy of books on the American Civil War is not only a piece of first-rate history,

but also a marvelous work of literature. Shelby Foote brings a skilled novelist's narrative power to this great epic. Many

know Foote for his prominent role as a commentator on Ken Burns's PBS series about the Civil War. These three books, however,

are his legacy. His southern sympathies are apparent: the first volume opens by introducing Confederate President Jefferson

Davis, rather than Abraham Lincoln. But they hardly get in the way of the great story Foote tells. This hefty three volume

set should be on the bookshelf of any Civil War buff. --John Miller. Continued below…

Product Description:

Foote's comprehensive history

of the Civil War includes three compelling volumes: Fort Sumter to Perryville, Fredericksburg

to Meridian, and Red River to Appomattox.

Collected together in a handsome boxed set, this is the perfect gift for any Civil War buff.

Fort Sumter to Perryville

"Here, for a certainty,

is one of the great historical narratives of our century, a unique and brilliant achievement, one that must be firmly placed

in the ranks of the masters." —Van Allen Bradley, Chicago

Daily News

"Anyone who wants to relive

the Civil War, as thousands of Americans apparently do, will go through this volume with pleasure.... Years from now, Foote's

monumental narrative most likely will continue to be read and remembered as a classic of its kind." —New York Herald Tribune Book Review

Fredericksburg to Meridian

"This, then, is narrative

history—a kind of history that goes back to an older literary tradition.... The writing is superb...one of the historical

and literary achievements of our time." —The Washington

Post Book World

"Gettysburg...is described

with such meticulous attention to action, terrain, time, and the characters of the various commanders that I understand, at

last, what happened in that battle.... Mr. Foote has an acute sense of the relative importance of events and a novelist's

skill in directing the reader's attention to the men and the episodes that will influence the course of the whole war, without

omitting items which are of momentary interest. His organization of facts could hardly be bettered." —Atlantic

Red

River to Appomattox

"An unparalleled achievement,

an American Iliad, a unique work uniting the scholarship of the historian and the high readability of the first-class novelist."

—Walker Percy

"I have never read a better, more

vivid, more understandable account of the savage battling between Grant's and Lee's armies.... Foote stays with the human

strife and suffering, and unlike most Southern commentators, he does not take sides. In objectivity, in range, in mastery

of detail in beauty of language and feeling for the people involved, this work surpasses anything else on the subject....

It stands alongside the work of the best of them." —New Republic

Recommended

Reading:

Hardtack & Coffee or The Unwritten Story of Army Life. Description: Most histories of the Civil War focus on battles and top brass. Hardtack and Coffee

is one of the few to give a vivid, detailed picture of what ordinary soldiers endured every day—in camp, on the march,

at the edge of a booming, smoking hell. John D. Billings of Massachusetts enlisted in the

Army of the Potomac and survived the hellish conditions as a “common foot soldier”

of the American Civil War. "Billings describes

an insightful account of the conflict – the experiences of every day life as a common foot-soldier – and a view

of the war that is sure to score with every buff." Continued below...

The

authenticity of his book is heightened by the many drawings that a comrade, Charles W. Reed, made while in the field. This

is the story of how the Civil War soldier was recruited, provisioned, and disciplined. Described here are the types of men

found in any outfit; their not very uniform uniforms; crowded tents and makeshift shelters; difficulties in keeping clean,

warm, and dry; their pleasure in a cup of coffee; food rations, dominated by salt pork and the versatile cracker or hardtack;

their brave pastimes in the face of death; punishments for various offenses; treatment in sick bay; firearms and signals and

modes of transportation. Comprehensive and anecdotal, Hardtack and Coffee is striking for the pulse of life that runs through

it.

Recommended Reading: The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (444

pages) (Louisiana State University Press) (Updated edition) (November 2007) Description: The Life of Johnny Reb

does not merely describe the battles and skirmishes fought by the Confederate foot soldier. Rather, it provides an intimate

history of a soldier's daily life--the songs he sang, the foods he ate, the hopes and fears he experienced, the reasons he

fought. Wiley examined countless letters, diaries, newspaper accounts, and official records to construct this frequently poignant,

sometimes humorous account of the life of Johnny Reb. In a new foreword for this updated edition, Civil War expert James I.

Robertson, Jr., explores the exemplary career of Bell Irvin Wiley, who championed the common folk, whom he saw as ensnared

in the great conflict of the 1860s. Continued below...

About Johnny Reb:

"A Civil War classic."--Florida Historical Quarterly

"This book deserves to be on the shelf of every Civil War modeler and enthusiast."--Model

Retailer

"[Wiley] has painted with skill a picture of the life of the Confederate

private. . . . It is a picture that is not only by far the most complete we have ever had but perhaps the best of its kind

we ever shall have."--Saturday Review of Literature

Recommended Reading: Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (488 pages) (Louisiana State

University Press). Description: This fascinating social history reveals that while the Yanks and the Rebs fought for very

different causes, the men on both sides were very much the same. "This wonderfully interesting book is the finest memorial

the Union soldier is ever likely to have. Continued below...

[Wiley] has written about the Northern troops with an admirable objectivity, with sympathy and understanding

and profound respect for their fighting abilities. He has also written about them with fabulous learning and considerable

pace and humor.

Recommended Reading:

Fields of Honor: Pivotal Battles of the Civil War,

by Edwin C. Bearss (Author), James McPherson (Introduction). Description: Bearss,

a former chief historian of the National Parks Service and internationally recognized American Civil War historian, chronicles

14 crucial battles, including Fort Sumter, Shiloh, Antietam, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Sherman's march through the

Carolinas, and Appomattox--the battles ranging between 1861 and 1865; included is an introductory chapter describing John

Brown's raid in October 1859. Bearss describes the

terrain, tactics, strategies, personalities, the soldiers and the commanders. (He personalizes the generals and politicians,

sergeants and privates.) Continued below...

The text is augmented by 80 black-and-white photographs and 19 maps. It is like touring the battlefields

without leaving home. A must for every one of America's countless Civil War buffs,

this major work will stand as an important reference and enduring legacy of a great historian for generations to come. "This

stout volume covers not only the pivotal American Civil War battles, but also the bloodiest and costliest battles." Also

available in hardcover: Fields of Honor: Pivotal Battles of the Civil War . .

|