|

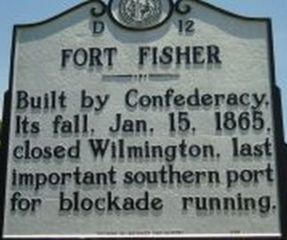

Battle of Fort Fisher

Fort Fisher Civil War History

Battle of Fort Fisher

Other Names: Second Battle of Fort Fisher;

Operations Against Fort Fisher; Assault on Fort Fisher; Operations Against Fort Fisher and Wilmington; Bombardment of

Fort Fisher

Location: New Hanover County

Campaign: Operations Against Fort Fisher and Wilmington (January-February 1865)

Date(s): January 13-15, 1865

Principal Commanders: Rear Adm. David D. Porter and Maj. Gen.

Alfred Terry [US]; Gen. Braxton Bragg, Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke, and Col. Charles Lamb [CS]

Forces Engaged: Expeditionary Corps, Army of the James [US];

Hoke's Division and Fort Fisher Garrison [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 2,000 total

Result(s): Union victory

| Battle of Fort Fisher Historical Marker |

|

Introduction: After the failure of his December Expedition Against Fort Fisher, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler was relieved of command. Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry was placed in command of a “Provisional

Corps,” including Paine's Division of U.S. Colored Troops, and supported by a naval force of nearly 60 vessels, to renew

operations against the fort.

After a preliminary bombardment directed by Rear Adm. David D. Porter on January

13, Union forces landed and prepared an attack on Maj. Gen. Robert Hoke's infantry line. On the 15th, a select force moved

on the fort from the rear. A valiant attack late in the afternoon, following the bloody repulse of a naval landing party carried

the parapet. The Confederate garrison surrendered, opening the way for a Federal thrust against Wilmington, the South's last

open seaport on the Atlantic coast.

Summary: The Second Battle of Fort Fisher was an assault

by the Union Army, Navy and Marine Corps against Fort Fisher, outside Wilmington, North Carolina, near the end of the American

Civil War. Sometimes referred to as the "Gibraltar of the South" and the last major coastal stronghold of the Confederacy,

Fort Fisher had tremendous strategic value during the war, providing a port for blockade runners supplying the Army of Northern

Virginia.

Background: Wilmington was the last major port open

to the Confederacy on the Atlantic seacoast. Ships leaving Wilmington via the Cape Fear River and setting sail for the Bahamas,

Bermuda or Nova Scotia to trade cotton and tobacco for needed supplies from the British were protected by the fort. Based

on the design of the Malakoff redoubt in Sevastopol, Russian Empire, Fort Fisher was constructed mostly of earth and sand.

This made it better able to absorb the pounding of heavy fire from Union ships than older fortifications constructed of mortar

and bricks. Twenty-two guns faced the ocean, while twenty-five faced the land. The sea face guns were mounted on 12-foot-high

batteries with larger, 45-and-60-foot batteries at the southern end of the fort. Underground passageways and bombproof rooms

existed below the giant earthen mounds of the fort. The fortifications kept Union ships from attacking the port of Wilmington

and the Cape Fear River.

On December 23, 1864, Union ships under Rear Admiral

David D. Porter commenced a naval bombardment of the fort, to little effect. On December 25, Union troops under Major General

Benjamin F. Butler began landing in preparation for a ground assault, but Butler withdrew them upon word of approaching Confederate

reinforcements.

| 2nd Battle of Fort Fisher Map |

|

| Civil War Fort Fisher Map |

Battle: Alfred Terry had previously commanded troops during

the Second Battle of Charleston Harbor and understood the importance of coordinating with the Union Navy. He and Admiral Porter

made well laid out plans for the joint attack. Terry would send one division of United States Colored Troops under Charles

J. Paine to hold off Hoke's division on the peninsula. Terry's other division under Adelbert Ames, supported by an independent

brigade under Colonel Joseph Carter Abbott, would move down the peninsula and attack the fort from the land face, striking

the landward wall on the river side of the peninsula. Porter organized a landing force of 2,000 sailors and marines to land

and attack the fort's sea face, on the seaward end of the same wall.

On January 13, Terry landed his troops in between Hoke and Fort Fisher. Hoke

was unwilling to risk opening the route to Wilmington and remained unengaged while the entire Union force landed safely ashore.

The next day Terry moved south towards the fort to reconnoiter the fort and decided that an infantry assault would succeed.

On January 15, Porter's gunboats opened fire on the sea face of the fort and

by noon they succeeded in silencing all but four guns. During this bombardment Hoke sent about 1,000 troops from his line

to Fort Fisher, however only about 400 were able to land and make it into the defense while the others were forced to turn

back. About this time the sailors and marines, led by Lieutenant Commander Kidder Breese, landed and moved against the point

where the fort's land and sea faces met, a feature known as the Northeast Bastion. The Union Army original plan was for the

naval force, armed with revolvers and cutlasses, to attack in three waves with the marines providing covering fire, but instead,

the assault went forward in a single unorganized mass. General Whiting personally led the defense and routed the assault,

with heavy casualties in the naval force.

The attack, however, drew Confederate attention away from the river gate,

where Ames prepared to launch his attack. At 2:00 in the afternoon he sent forward his first brigade, under the command of

Brevet Brigadier Newton Martin Curtis, as Ames waited with the brigades of Colonels Galusha Pennypacker and Louis Bell. An

advance guard from Curtis's Brigade used axes to cut through the palisades and abatis. Curtis's Brigade took heavy casualties

as it overran the outer works and stormed the first traverse. At this point Ames ordered Pennypacker's Brigade forward, which

he accompanied into the fort. As Ames marched forward, Confederate snipers zeroed in on his party, and cut down a number of

his aides around him. Pennypacker's men fought their way through the riverside gate, and Ames ordered a portion of his men

to fortify a position within the interior of the fort. Meanwhile, the Confederates turned the cannons in Battery Buchanan

at the southern tip of the peninsula and fired on the northern wall as it fell into Union hands. Ames observed that Curtis's

lead units had become stalled at the fourth traverse, and he ordered forward Bell's Brigade, but Bell was killed by sharpshooters

before ever reaching the fort. Seeing the Union attackers crowd into the breach and interior, General Whiting took the opportunity

to personally lead a counterattack. Charging into the Union soldiers, Whiting received multiple demands to surrender, and

when he refused he was shot down, severely wounded.

Porter's gunboats helped maintain the Federal momentum. His gunners' aim proved

to be deadly accurate and began clearing out the defenders as the Union troops approached the sea wall. Curtis's troops gained

the heavily contested 4th traverse. Colonel Lamb began gathering up every last soldier in the fort, including sick and wounded

from the hospital, for a last-ditch counterattack. Just as he was about to order a charge, he fell severely wounded and was

brought next to General Whiting in the fort's hospital. General Ames made a suggestion for the Union troops to entrench in

their current positions. Upon hearing this notion, a frenzied Curtis grabbed a spade and threw it over Confederate trenches

and shouted, "Dig Johnnies, for I'm coming for you." About an hour into the battle, Curtis fell wounded while going back to

confer with Ames. Colonel Pennypacker also fell wounded before the battle ended.

| Fort Fisher History |

|

| Fort Fisher Defenses |

| Fort Fisher Civil War History |

|

| Cape Fear Defense System |

The grueling battle lasted for hours, long after dark, as shells plunged in

from the sea and General Ames struggled with a division that became increasingly disorganized as his regimental leaders and

all of his brigade commanders fell dead or wounded. General Terry sent forward Abbott's brigade to reinforce the attack, then

joined Ames in the interior of the fortress. Meanwhile, in Fort Fisher's hospital, Colonel Lamb turned over command to Major

James Reilly, and General Whiting sent one last plea to General Bragg to send reinforcements. Still believing the situation

in Fort Fisher was under control and tired of Whiting's demands, Bragg instead dispatched General Alfred H. Colquitt to relieve

Whiting and assume command at Fort Fisher. At 9:30 p.m. Colquitt landed at the southern base of the fort just as Lamb, Whiting

and the Confederate wounded were being evacuated to Battery Buchanan.

At this point, the Confederate hold on Fort Fisher was untenable. The seaward batteries had been silenced,

almost all of the north wall had been captured, and Ames had fortified a bastion within the interior. Terry, however, had

concluded to finish the battle that night. Ames, ordered to maintain the offensive, organized a flanking maneuver, sending

some of his men to advance outside the land wall, and come up behind the Confederate defenders of the last traverse. Within

a few minutes the Confederate defeat was unmistakable. Colquitt and his staff rushed back to their rowboats just moments before

Abbott's men seized the wharf. Major Reilly held up a white flag and walked into the Union lines to announce the fort would

surrender. Just before 10 p.m. General Terry rode to Battery Buchanan to receive the official surrender of the fort from General

Whiting.

Aftermath: The loss of Fort Fisher sealed the fate

of the Confederacy's last remaining sea port and the South was cut off from global trade. Also, many of the military supplies

which the Army of Northern Virginia depended upon came through Wilmington; there were no remaining seaports near Virginia

that the Confederates could use practically. It also ended any chance of European recognition, being viewed "by many as the

final nail in the Confederate coffin." A month later, a Union army under General John M. Schofield would move up the Cape

Fear River and capture Wilmington.

On January 16, Union celebrations were dampened when the fort's magazine

exploded killing and wounding 200 Union soldiers and Confederate prisoners that were sleeping on the roof of the magazine

chamber or nearby. U.S. Navy Ensign Alfred Stow Leighton died in the explosion while in charge of a squad trying to recover

bodies from the fort parapet. Although several Union soldiers initially thought Confederate prisoners were responsible, an

investigation opened by Terry concluded that unknown Union soldiers (possibly drunken marines) had entered the magazine with

torches and ignited the powder.

William Lamb survived the battle but spent the next seven years on crutches.

General Whiting was taken prisoner and died while in Federal captivity. Colonel Galusha Pennypacker's wounds were thought

to have been fatal and General Terry assured the young man he would receive a brevet promotion (where the person promoted

would be authorised to wear the insignia of the new rank, but was paid the wages of his original rank) to brigadier general.

Pennypacker did receive a brevet promotion as Terry had promised but on February 18, 1865, he received a full promotion to

brigadier general of volunteers at age 20. He remains the youngest person to have held the rank of general in the U.S. Army

(apart from the Marquis de Lafayette). Newton Martin Curtis also received a full promotion to brigadier general and both he

and Pennypacker received the Medal of Honor for their part in the battle. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton made an unexpected

visit to Fort Fisher where General Terry presented him with garrison's flag.

| Second Battle of Fort Fisher |

|

| Second Battle of Fort Fisher |

Analysis: After Butler's removal, he was replaced by Major

General Alfred Terry, and the operation was dubbed "Terry's expedition." Admiral Porter was again in charge of the naval attack.

They waited until January 12, 1865, for the second attempt.

They started with a strong bombardment from 56 ships for two and a half

days. This targeted both of Fort Fisher's fronts. On January 15 at 3 p.m., 8,000 Union soldiers (who landed on January 12)

attacked at the Land Face. At the same time 2,000 Navy Sailors armed with small arms made a frontal assault on the fort's

northeast bastion. As the bombardment continued, the naval attack was repulsed while the Union infantry entered the fortification

through Shepherd Battery. Thus, the Confederate soldiers found themselves battling behind their walls, and were forced to

retreat.

Altogether, the land battle lasted six hours. At nighttime, General William

Whiting, who had been wounded during the battle, surrendered as Commander of the District of Cape Fear. He was then imprisoned;

he died in prison March 10, 1865. The Confederates who had been captured and were not wounded were taken to the Federal Prison

located at Elmira, New York, and assigned to Company E, 3rd Division of Prisoners. Those Confederates that were wounded were

admitted to Hammond General Hospital and upon recovery were discharged and transferred to the main prison complex. Hammond

General Hospital was outside the Prison Compound at Point Lookout, Maryland. Many of the guards in the Prison at Point Lookout

were former slaves that had joined the Union ranks.

Recommended

Reading: Confederate Goliath: The Battle of Fort

Fisher. From Publishers Weekly: Late in the Civil War, Wilmington, N.C., was the sole remaining seaport supplying Lee's army at Petersburg,

Va., with rations and munitions. In this dramatic account, Gragg describes the

two-phase campaign by which Union forces captured the fort that guarded Wilmington and the subsequent occupation of the city

itself--a victory that virtually doomed the Confederacy. In the initial phase in December 1864, General Ben Butler and Admiral

David Porter directed an unsuccessful amphibious assault against Fort

Fisher that included the war's heaviest artillery bombardment. Continued

below…

The second

try in January '65 brought General Alfred Terry's 9000-man army against 1500 ill-equipped defenders, climaxing in a bloody

hand-to-hand struggle inside the bastion and an overwhelming Union victory. Although historians tend to downplay the event,

it was nevertheless as strategically decisive as the earlier fall of either Vicksburg or Atlanta. Gragg

has done a fine job in restoring this important campaign to public attention. Includes numerous photos.

Recommended

Reading: Hurricane of Fire: The Union Assault on Fort Fisher

(Hardcover). Review: In December 1864 and January 1865, Federal forces launched the greatest amphibious assault the world

had yet seen on the Confederate stronghold of Fort Fisher,

near Wilmington, North Carolina.

This was the last seaport available to the South--all of the others had been effectively shut down by the Union's

tight naval blockade. The initial attack was a disaster; Fort

Fisher, built mainly out of beach sand, appeared almost impregnable against

a heavy naval bombardment. When troops finally landed, they were quickly repelled. Continued below…

A second attempt

succeeded and arguably helped deliver one of the death blows to a quickly fading Confederacy. Hurricane of Fire is a work

of original scholarship, ably complementing Rod Gragg's Confederate Goliath, and the first book to take a full account of

the navy's important supporting role in the assault.

Recommended

Reading: Rebel Gibraltar: Fort Fisher and Wilmington, C.S.A. Description: Even before the rest of North Carolina joined her sister states in secession,

the people of the Lower Cape Fear were filled with enthusiasm for the Southern Cause - so much so that they actually seized

Forts Johnston and Caswell, at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, weeks before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. When

the state finally did secede, Wilmington became the most important port city of the Confederacy, keeping Robert E. Lee

supplied with the munitions and supplies he needed to fight the war against the North. Continued below…

Dedicated soldiers

like William Lamb and W.H.C. Whiting turned the sandy beaches of southern New Hanover and Brunswick Counties into a series

of fortresses that kept the Union

navy at bay for four years. The mighty Fort Fisher

and a series of smaller forts offered safe haven for daring blockade runners that brought in the Confederacy's much-needed

supplies. In the process, they turned the quiet port of Wilmington into a boomtown. In this book that was fifteen years in the making, James

L. Walker, Jr. has chronicled the story of the Lower Cape Fear and the forts and men that guarded it during America's bloodiest conflict, from the early days of the war to the fall of Wilmington in February 1865.

Recommended

Reading: The Wilmington Campaign and the Battle for Fort Fisher, by Mark A. Moore. Description:

Full campaign and battle history of the largest combined operation in U.S.

military history prior to World War II. By late 1864, Wilmington

was the last major Confederate blockade-running seaport open to the outside world. The final battle for the port city's protector--Fort Fisher--culminated

in the largest naval bombardment of the American Civil War, and one of the worst hand-to-hand engagements in four years of

bloody fighting. Continued below…

Copious illustrations,

including 54 original maps drawn by the author. Fresh new analysis on the fall of Fort Fisher, with a fascinating comparison

to Russian defenses at Sebastopol during the Crimean War. “A tour de force. Moore's Fort Fisher-Wilmington Campaign is the best publication of this

character that I have seen in more than 50 years.” -- Edwin C. Bearss, Chief Historian Emeritus, National Park Service

Recommended

Reading: The Wilmington

Campaign: Last Departing Rays of Hope. Description: While prior books on the battle to capture Wilmington,

North Carolina, have focused solely on the epic struggles for Fort Fisher, in many respects this was just

the beginning of the campaign. In addition to complete coverage (with significant new information) of both battles for Fort Fisher, "The Wilmington Campaign" includes the first

detailed examination of the attack and defense of Fort Anderson. It also features blow-by-blow accounts of the defense of the Sugar Loaf Line

and of the operations of Federal warships on the Cape Fear River. This masterpiece of military

history proves yet again that there is still much to be learned about the American Civil War. Continued below…

"The Wilmington

Campaign is a splendid achievement. This gripping chronicle of the five-weeks' campaign up the Cape Fear River adds a crucial dimension

to our understanding of the Confederacy's collapse." -James McPherson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Battle Cry of Freedom

Recommended

Reading: A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron over Wood. Description: This

landmark book documents the dramatic history of Civil War ironclads and reveals how ironclad warships revolutionized naval

warfare. Author John V. Quarstein explores in depth the impact of ironclads during the Civil War and their colossal effect

on naval history. The Battle of Hampton Roads was one of history's greatest naval engagements. Over the course of two days

in March 1862, this Civil War conflict decided the fate of all the world's navies. It was the first battle between ironclad

warships, and the 25,000 sailors, soldiers and civilians who witnessed the battle vividly understood what history would soon

confirm: wars waged on the seas would never be the same. Continued below…

About the Author: John V. Quarstein is an award-winning author and historian. He is director

of the Virginia

War Museum in Newport News and chief historical advisor for The Mariners' Museum's new USS Monitor Center

(opened March 2007). Quarstein has authored eleven books and dozens of articles on American, military and Civil War history,

and has appeared in documentaries for PBS, BBC, The History Channel and Discovery Channel.

Recommended Reading: Masters of the Shoals: Tales of the Cape Fear Pilots Who Ran the Union Blockade. Description: Lavishly illustrated stories of daring harbor pilots who risked their lives

for the Confederacy. Following the Union's blockade of the South's waterways, the survival

of the Confederacy depended on a handful of heroes-daring harbor pilots and ship captains-who would risk their lives and cargo

to outrun Union ships and guns. Their tales of high adventure and master seamanship became legendary. Masters of the Shoals

brings to life these brave pilots of Cape Fear

who saved the South from gradual starvation. Continued below…

REVIEWS:

"A valuable and meticulous accounting of one chapter of the South's failing struggle against the Union." -- Washington Times 03/06/04

"An interesting picture of a little appreciated band of professionals...Well documented...an easy read." -- Civil War

News June 2004

"An interesting picture of a little appreciated band of professionals...Will be of special interest to Civil War naval

enthusiasts." -- Civil War News May 2004

"Offers an original view of a vital but little-known aspect of blockade running." -- Military Images 03/01/04

"Surveys the whole history of the hardy seamen who guided ships around the Cape

Fear's treacherous shoals." -- Wilmington

Star-News 10/26/03

"The story [McNeil] writes is as personal as a family memoir, as authoritative and enthusiastic as the best history."

-- The Advocate 11/15/03

“Outstanding and compelling depictions of seamen courage and tenacity...Heroic, stirring, and gripping stories

of the men that dared to confront the might and power of the US Navy.” – americancivilwarhistory.org

Sources: National Park Service; Library of Congress; Chaitin, Peter M., ed.

(1984). The Coastal War: Chesapeake to the Rio Grande. Alexandria, Va: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-4732-0; Fonvielle, Chris

E. Jr. (1997). Last Rays of Departing Hope: The Wilmington Campaign. Campbell, CA.: Savas Publishing Company. ISBN 1-882810-09-0;

Gragg, Rod (1994). Confederate Goliath: The Battle of Fort Fisher. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807119174;

Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

|