|

Battle of Shiloh Civil War

Shiloh and Pittsburg Landing

by William Swinton

(War correspondent for the New York Times newspaper)

Twelve Decisive Battles Of The War

Originally Published in 1867

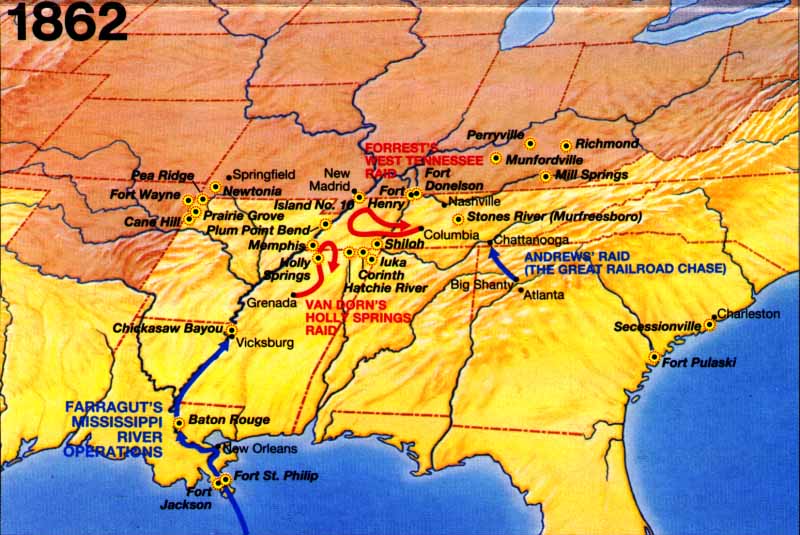

| Civil War Battle of Shiloh Map |

|

| Shiloh Battle and Pittsburg Landing Civil War Battlefield Map |

| Battle of Shiloh Civil War Map |

|

| Western Campaign with Battle of Shiloh and Pittsburg Landing Civil War Map |

I.

PRELUDE TO SHILOH.On

the westerly bank of the Tennessee, 219 miles from its mouth, is the historic spot of Pittsburg Landing. Its site is just

below that great bend in the river, where, having trended many miles along the boundary-line of Alabama, it sweeps northerly

in a majestic curve, and thence flowing past Fort Henry, pours its waters into the Ohio. The neighboring country is undulating,

broken into hills and ravines, and wooded for the most part with tall oak-trees and occasional patches of undergrowth. Fens

and swamps, too, intervene, and, at the spring freshets, the back-water swells the creeks, inundating the roads near the river's

margin. It is, in general, a rough and unprepossessing region, wherein cultivated clearings seldom break the continuity of

forest. Pittsburg Landing, scarcely laying claim, with its two log cabins, even to the dignity of a. hamlet, is distant a

dozen miles north-easterly from the crossing of the three State lines of Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee--a mere point

of steamboat freighting and debarkation for Corinth, eighteen miles south-west, for Purdy, about as far north-west, and for

similar towns on the adjoining railroads. The river banks at the Landing rise quite eighty feet, but are cloven by a series

of ravines, through one of which runs the main road thence to Corinth, forking to Purdy. Beyond the crest of the acclivity

stretches back a kind of table-land, rolling and ridgy, cleared near the shores, but wooded and rough further from the river.

A rude log chapel, three miles out, is called Shiloh Church; and, just beyond, rise not far from each other two petty streams,

Owl Creek and Lick Creek, which, thence diverging, run windingly into the Tennessee, five miles apart, on either side of the

landing.

On this rugged, elevated plateau, encompassed by the river and its little

tributaries like a picture in its frame, lay encamped on the night of the 5th of April, 1862, five divisions of General Grant's

Army of West Tennessee; with a sixth, five miles down the bank, at Crump's Landing. Thrust though it was far out into the

enemy's domain, yet the very scene of its encampment told more strongly than any language how absolutely secure this army

felt from any hostile visit, and how unsuspicious it was of any shock of battle. The camps had been fixed on the bank nearest

the enemy, while the other was equally available. The five divisions, irregularly grouped between the creeks and river, were

palpably positioned without any regard to order of battle or to possible attack. Behind, rolled a broad and deep river, without

fords, without bridges, without transportation. Before, not a single spadeful of earth had been thrown up for intrenchment

during the month's sojourn, whether in front of the advance divisions, or across the roads leading into the camp, or at the

fords on the flanks. Not a single cavalryman patrolled the outer walks; the scanty infantry outposts lay within a mile of

the main line, and their unconcealed camp-fires flared high and cheerily into the damp April air. The few sentinels were wont

to chat and laugh aloud, and, whenever morning came, their pieces were irregularly discharged, merely to clear them of their

loads. Within the noiseless rows of white tents lining and dotting the rough plateau, the slumberous army now dreamt peacefully

of home, or of that day yet distant when it would march on the enemy's stronghold at Corinth, joined by the column of Buell.

At that moment, the leading division of Buell's army of the Ohio lay at Savannah, nine miles down the river on the other bank.

Wearied that night with their four days' march from Columbia, Nelson's men slept heavily. A long rest had been promised to

them, to be broken only the next day by a formal Sunday inspection, and leisurely during the week ensuing it would join the

associate army of West Tennessee; for transportation had not yet been made ready for its passage of the river, nor had General

Halleck yet come down from St. Louis to direct the movement on Corinth, for which it had marched. Behind Nelson, the rest

of Buell's army trailed that night its line of bivouac fires full thirty miles backward on the road to Columbia.

Silent in Shiloh woods yonder, within sight of Grant's camp-fires and within

sound of his noisy pickets, lay grimly awaiting the dawn, 40,000 Confederate soldiers. It was the third of the three great

armies drawn together that night towards Pittsburg Landing,--an army supposed by its fourscore thousand dormant foes, from

Commanding-General to drummer-boy, to be lying perdu behind its Corinth fieldworks, twenty miles away. It had crept

close to the Union lines, three fourths of a mile from the pickets, less than two from the main camp--so close that, throughout

the night, the bivouac hum and stir and the noisy random shots of untrained sentinels on the opposing lines indistinguishably

mingled. This stealthily-moved host lay on its arms, weary after a hard day's march over miry roads on the 4th, a day's forming

on the 5th, and a bivouac in the drenching rain of the night intervening. No fires were lighted on the advanced lines, and,

farther back, the few embers, glowing here and there, were hidden in holes dug in the ground. Most of the men lay awake, prone

in their blankets, or chatted in low tones, grouped around the stacked arms, awaiting the supplies which commissaries and

staff-officers were hurrying from the rear; for, with the improvidence of raw troops, they had already spent their five days'

rations at the end of three, and, were ill-prepared to give battle. But others oppressed with sleep, had for the time forgotten

both cold and hunger.

Sheltered in the gloom of tall trees, and under the watch and ward of chosen

sentinels, patrolling and challenging with low, steady voice, a council of Confederate generals gathered in the cleared spot

which, at converging paths, formed the head-quarters. A small fire of logs crackling and sputtering in the centre threw a

strange light on the surrounding figures. A drum served for writing-desk near the firelight, and a few camp-stools for furniture,

eked out by blankets spread upon the ground.

Foremost in the group stood Albert Sydney Johnston, the Commander-in-Chief.

Tall, erect, well-knit, and powerful, his dignified and martial figure gained effect by the gray military cloak which protected

it from the chilly evening. His face, bronzed and set by the campaigns of two and forty years in the Black Hawk war, in the

Texan struggle for independence, in the war with Mexico, and for many years past in Indian outpost service through Utah and

California, was a trustworthy index to the man. The firm mouth and chin and the steadfast, sunken eyes, showed a soldier resolute,

self-controlled, thoughtful, and fearless. Grave, modest, and reticent always, he seemed at this council even more abstracted

than his wont. Often he moved from the fire to the edge of the group as if walking away to ruminate his own thoughts, and

anon returned to take part in the discussion. He was, indeed, greatly impressed with his responsibility; and in his supreme

devotion to his cause, had no moment to spare for personal forebodings. Before another sunset, this soldier was fated to have

fought his last battle.

In marked contrast to the Scotch features and bearing of Johnston, was his

associate, Beauregard. Walking rapidly to and fro, with his lithe and slender figure divested of its outer cloak, he spoke

tersely and spiritedly with a tinge of French accent, on the prospects of the morrow. His face, with its small, regular features,

pointed beard, and keen eyes, showed somewhat the effect of the illness under which he was still laboring; but his bearing

was entirely soldierly, his short step was energetic and firm, his voice clear and strong. Obviously vexed at the day's mishaps

of manoeuvre, he only awaited anxiously for success in the coming battle, in which he had a personal as well as a patriotic

stake. For already the brilliant promise of his youthful Mexican career had come to fruition, and with the laurels of Fort

Sumter and Manassas still fresh upon him, he had come to restore the Confederate fortunes in the West.

Near by was Hardee, whose corps lay closest to the Union outposts, a Georgian,

but matching the inherited foreign air of Beauregard, by one acquired by long military education in France. As compiler of

the Infantry Tactics, and Commandant of Cadets at West Point, and as a fine theoretical soldier, his opinions received due

weight. Physically, he appeared tall, broad-shouldered, and muscular, and from his good-humored face did not seem to take

amiss a little rallying, which even the grave occasion did not forbid a brother officer from indulging, on his gallantry in

other fields than those of war.

Breckinridge, commander of the reserves, and rather of forensic than of martial

renown, a man of fine features and imposing appearance, lay silent upon his blanket, and did not obtrude his views upon older

soldiers. In truth, his general opinions were well-known to be like Beauregard's, strongly aggressive. Vice-President, and

almost President of the Union, little more than a twelvemonth gone, he was still quite as much Kentuckian as Confederate;

and to "redeem" Kentucky he had urged, long before the fall of Fort Henry, an offensive campaign against Louisville.

Bragg, proud of his well-drilled Pensacola corps, and vaunting in general

the power of discipline, was, nevertheless, in marked physical contrast to the uniform military bearing of the others. His

face was wan and haggard, its features being rude and irregular, and his body stooping. His beard was iron-gray, and growing

together over the bridge of his nose were a pair of bushy black eyebrows, under which his sharp and restless eyes seemed befitting

to his character as a thorough disciplinarian, and to his well-known tartness of temper. Even before the war his fame was

national, and his name, and that of his battery, as inseparably linked as Taylor's with the historic field of Buena Vista.

Lieutenant General Polk, whilom Bishop of Louisiana who,--a West Pointer by

education,--had exchanged the crosier for the sword, was the last of the main figures of the group. He was above the middle

height, and broad-chested, and his open face denoted courtesy and courage as well as a fine intelligence.

The council was long and animated. Beauregard and Bragg, the chief speakers,

talked often and earnestly, while Polk and Breckinridge said little, in the presence of these more famous soldiers. There

was much that was vexatious. The weather had been contrary from the start, the country was hostile to campaigning, the raw

troops were unused to marching and manoeuvre, their officers not less so. Already a day had been lost; for the night before,

the rain descending in torrents, had drenched the men in bivouac and made the narrow and tortuous roads, always bad at best,

next to impassable. The artillery and trains and even the infantry columns struggled painfully through the mire, so that what

with raw troops and raw officers, with carelessly examined ground and roads twisting confusingly through brake and swamp,

joined to some misapprehensions on the part of corps commanders, two days had been expended in getting hither from Corinth.

Instead of attacking at dawn of the 5th, dusk found the troops wet, hungry, and exhausted, and just brought into position.

The whole move had been based on striking a blow before Buell should come up, and every minute was golden.

The wretched organization of the army was another subject of discussion, and

of ill-boding. Two days' experience had shown its lamentable defects. Bragg openly declared that many officers in the army

were not equal to the men whom they were expected to command; Beauregard regretted the want of engineers to inform him of

the terrain of the morrow's battle-field; and all the generals found much to apprehend from the imperfect staff organization,

while the responsibility for these and other failings, was by more than one speaker laid directly at the door of the Richmond

authorities, where unquestionably it belonged.

As the discussion, however, went on, and the encouraging omens were in turn

reviewed, the tone of the council became firm and confident. The enemy had been secretly approached and the surprise would

be complete. He was found most lamentably unprepared--the general absent at his head-quarters, nine miles down the river,

and on the other shore at that, with his camp unintrenched, not one cavalry picket out, with his outposts near his main line,

with his troops badly placed, and finally, with no pontoons or transportation on the river, to which it was proposed to drive

him. Anxious inquiry was made, indeed, concerning the whereabouts of Buell; but on this all important point, Beauregard, from

the last report of the spies, who had brought him fresh news of each day's march of Buell, and each night's bivouac, was able

to declare him at least one day's march from the battlefield, and with no boats ready to cross him. Moreover, the Confederate

troops, despite their hard initiation, were full of fire and confident of victory. In numbers, they were nearly equal to Grant's

forces, who were, also, for the most part raw and indifferently organized; while against the conquerors at Donelson, could

be matched Bragg's fine corps from Pensacola.

Ten o'clock came and passed before the officers had all separated, but at

length the early start arranged for the morrow, provoked the suggestion of retirement. All parted with high hopes. Of the

associate commanders, Johnston was clearly resolved to wipe out the hasty and unjust reproach cast on him after Donelson,

while Beauregard, forgetting alike his sickness and his disappointment at the ill-omened delay, pointing the departing officers

towards the Tennessee, said, with a confident smile, "Gentlemen, to-morrow night we sleep in the enemy's camp."

It was the eve of Shiloh.

The

situation just portrayed had followed upon a noteworthy chain of events. With the fall of Fort Donelson, crumbled forever

the entire first line of Tennessee defence--the line of the Cumberland, as it may be called--stretching due east from Columbus,

through Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, and Nashville, to Mill Spring, and onward to the Alleghanies. But the recoil was slight,

for a secondary line had already been stretched out and was a-fortifying, "select a defensive position below;" and the point

chosen was forty miles down the Mississippi, embracing, Island No. 10, the main land in Madrid Bend, and the village there.

This, being rapidly intretched, became the point d'appui for the left of what was hastily pencilled as the second grand

Confederate line for the defence of the easterly slope of the Mississippi Valley. From Island No. 10 it was at first popularly

believed the cordon would strike easterly through Jackson, the head-quarters of one Confederate army, to Murfreesboro, the

head-quarters of another, and thence to Cumberland Gap, thus retiring the Confederate right and centre through a vast segment,

and abandoning all East Kentucky and much of Tennessee, but keeping the left strong and fast as with the death-clutch on the

Mississippi, and fairly protruding the line at Island No. 10. But great events forced the abandonment of this line before

it had acquired consistency. The fall of Donelson had developed a new problem for the Union commanders, since two lines of

advance into the Confederacy were now presented by the physical geography of the region. One runs south-easterly through Nashville

to the rocky eyrie of Chattanooga, the future route of Rosecrans--thence onward to the ocean, the future path of Sherman:

the other is the line of the Mississippi. It was needful to fight them both out in conquering the Confederacy, and, accordingly,

the absolute importance of neither could be overrated. But, it having been wisely resolved no longer, as at the outset, to

move over both at once, it remained to give to one or other the priority in time. The choice fell upon the Mississippi route,

for many potent reasons. The repossession of the Mississippi was one of those grand national ideas which are so powerful in

moving a people to patriotic effort. It was to reopen the Mississippi to navigation, that the West had risen en masse,

recognizing in its obstruction by insurgent batteries an act quite as astounding as the men on the other flank of the Alleghanies

had discovered in the menaced siege of Washington. Such a success would be more palpable and grander than the mere penetration

of half a dozen States in any other direction--and proportionally add prestige to the Union arms, dishearten the Confederates,

and challenge the applause of the world. These were general considerations: there were special ones more important. The campaign

on the Mississippi allowed naval co-operation; not so that towards Chattanooga. The latter required grand preparations of

supplies and reinforcement, and the opening and holding of long lines of railroad communication. All that was conquered of

the river could be easily held--not so, as Buell found, with the road to Chattanooga; for a move to the south-east, besides

exposing the flanks and rear of the column itself, would leave all Western Kentucky and Tennessee to the returning enemy,

and unravel the victorious campaign as far back as Louisville or Cairo. Finally, it ran the hazard of a series of battles

deep in the recesses of the Confederacy.

There was still another class of weighty and special circumstances. The Confederates

were holding points all along the Mississippi--at Columbus, Island 10, Fort Pillow, Memphis,-- and a column moving down the

left bank would cut them all off, with their garrisons, armaments, and strategic positions. It might even interpose between

Johnston's Tennessee army at Murfreesboro', and Beauregard's Mississippi army at Corinth, and attack one before the other

could come up. Now the second line of Confederate defence chosen by Johnston was that of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad--too

obvious an one for a doubt of its selection to rest in the minds of either of the contestants. It is true that, as we shall

presently see, Beauregard was undermining all these schemes and reducing this second line to one of little moment, his primary

thought being a new offensive campaign, which should provide its own parry in its reeling stroke. But this conception the

Union generals did not know; and never, indeed, discovered it till its consummation on the battle-ground of Shiloh. What they

did learn, after their plans were formed, was that Johnston had joined Beauregard, and hence so much of the scheme as contemplated

the separation of these officers, had come too tardy off. But there was, then, of course, only the more urgency for the original

plan, that of concentrating everything on the Mississippi line, so as to cut off Memphis and the river forts, to seize another

section of the river, and, above all, to sever the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. The importance of this great Southern

central line of transportation between East and West proclaims itself, without need of description, along its whole length,

from the Mississippi to the sea. All the leading Union generals urged a snapping of that railroad chain--Buell urged it, Halleck

urged it, Grant urged it. Indeed, the two latter officers at first moved without waiting for a concentration of force, and

only Johnston's junction with Beauregard warned them of its necessity: then, Buell's army, which had already been pressingly

tendered several times, was at last joined in the grand campaign.

The great railroad line which Halleck was now bent on permanently securing,

as the main object of the campaign, could have been tapped at any one of several points. But everything pointed to an advance

up the Tennessee as the most practicable. It was the shortest route thitherward; and, besides, being so largely accomplished

in transports, and with a water line of communication kept open by the navy, it would not consume the spring with vast preparations

of troops and trains for a land advance. Moreover, it threatened the rear of all the enemy's positions on the Mississippi--Memphis,

Randolph, New Madrid, Island No. 10--and directly co-operated with Pope and Foote, who were hammering and tunnelling their

way down the river, first at and around Columbus, and afterwards at Island 10. But, above all, it was as if, straight from

Fort Henry, there lay a direct highway, patent, possible, even now opened up through Tennessee to Alabama, and directly beckoning

to conquest--a broad highway whereon the gun-boats--those terrors of the Confederates, and inestimable Union allies--could

carry their flag unchallenged fourscore miles into the enemy's domain.

Up the broad stream, accordingly, Halleck promptly pushed the conquerors of

Donelson. This fort surrendered on the 16th day of February; and five divisions of Grant's army were made ready, and embarked

on transports early in March. On the 4th of March (for reasons it is needless to exhume) General Grant was ordered to turn

over his forces to General C. F. Smith. Halleck's original design was to establish the expedition as far up the river as Florence,

to which point Phelps's gunboat reconnoissance with the Tyler and Lexington had penetrated on the 8th of February preceding.

But a reconnoissance of the same boats on the 1st of March, was checked by a hostile battery at Pittsburgh Landing, and had

disclosed the enemy in a formidable position at Corinth; so that it became out of the question to go higher up. Indeed, the

first point of landing and depot of supplies was very wisely fixed on the right or easterly bank of the Tennessee, at Savannah.

Thence it was resolved to cross the army to Pittsburgh Landing, in support of two columns to be despatched to cut the railroad,

one above and the other below Corinth; and if these were successful, to move at once against the enemy's position. Accordingly,

the Tyler steamed to Danville Bridge, twenty-one miles above Fort Henry, to await the transports; and these, arriving on the

9th, with General Smith and a large portion of his army, and Sherman's division in advance, were conveyed without molestation

to Savannah, where they debarked during the 11th. The next night Wallace's division was put ashore at Crump's Landing, five

miles below Pittsburgh Landing; on the 14th, at the latter point, they were quickly joined by Smith's own division and those

of McClernand and Prentiss, and the movement was then complete. Instantly on landing, General Wallace was sent out on the

direct road from Crumps's to Purdy, and, without opposition, tore up, a few miles north of that village, half a mile of the

Mobile and Ohio Railroad, which runs from Corinth to Columbus. But the Memphis and Charleston Railroad was too far beyond

for him to attack; and Sherman's column, sent against the latter road, south of Corinth, proved unsuccessful, because the

river rising rapidly had overflowed in deep back water between him and his objective. At this time, unhappily, General Smith

fell sick of a mortal illness. "That elegant soldier," said McClellan; that "gallant and elegant officer!" said Sherman admiringly,

four years later, adding: "Had he lived, probably some of us younger fellows would not have attained our present positions."

Smith's own division was turned over to General W. H. L. Wallace; and, meanwhile, the command of the whole expedition had

again devolved upon General Grant, who, emerging from his brief cloud, was restored to command on the 14th, and arrived at

the head-quarters at Savannah on the 17th of March. Thereupon three weeks of inactivity elapsed, broken only by the battle-thunders

of Shiloh.

Meanwhile, a second army was faring forth to the field. March had found Buell

and Halleck in parallel commands, the one at St. Louis, in the, Department of the Missouri, the other at Nashville, in the

Department of the Ohio. Buell, first to detect the clandestine withdrawal of Johnston from his front to the Memphis and Charleston

Railroad, urgently suggested a movement up the Tennessee in force, which movement, however, General Halleck had already thought

of. Finding their views in unison, Buell next repeatedly tendered, by telegram, his own forces for co-operation; and at length

an excellent opportunity for accepting this proposal came on the 12th of March, when the two departments were united as the

Department of the Mississippi, under General Halleck. The latter officer then telegraphed Buell to move, and Buell on the

very same night, the 15th, put in motion his cavalry, followed next morning by McCook's division of infantry. McCook reached

Columbia on the 17th, but found that, while all the other bridges on the route had been saved by the promptness of Buell's

march, those over Duck River had been destroyed by the enemy. The river was then forty feet deep, and though gradually receding,

it would not do to wait till it became fordable; and the engineer corps worked strenuously at building a bridge, which, however,

was not finished till the 31st, when all five divisions again moved forward briskly and handsomely to Savannah, the point

of rendezvous fixed by General Halleck. There, Buell was led to expect, according to his instructions, that he would find

General Grant and his army. On the 28th, General Halleck informed General Buell that Grant would attack the enemy "as soon

as the roads are passable," and that the latter was receiving reinforcements for that purpose. Buell had assigned the 5th

day of April for the arrival of his advance division, Nelson's at Savannah. But, on the 4th, General Grant sent Nelson a despatch,

stating that he need not hurry, as the transportation for taking him across to the left bank was not yet ready, and would

not be ready till the 8th; the day, by the way, after the closing battle of Shiloh. The next day, in response to a suggestion

from Buell, that perhaps it would be well to strike the river twenty miles higher up than Savannah, by the Waynesboro' road,

which would have brought him opposite Hamburg,--Halleck telegraphed "You are right about concentrating at Waynesboro'; future

movements must depend on those of the enemy." A hundred such indications show, like that of the position of Grant's army,

already spoken of, how all the Union generals supposed their task was to be one of attack, not of defence,--a deliberate forward

movement on Corinth, to be undertaken some days later. But, as good fortune would have it, Halleck's despatch did not reach

Buell till he had pushed beyond Waynesboro' in his hasty strides, and Nelson also pressed on to Savannah at Buell's originally

appointed time, instead of making the delay which the despatch from Grant had authorized. Despite the rains and the bad roads

(which, at this same time, lost the Confederates the fatal twenty-four hours in their march from Corinth), the eighty-two

miles from Columbia to Savannah were made by Nelson in four days, and his division lay at Savannah on the eve of Shiloh. Behind,

at convenient distances, were the divisions of Crittenden, McCook, Wood, and Thomas.

While the Union Generals were thus eager with their plot, their antagonists

had secretly dressed a counterplot, the master-spirit in whose devising was Beauregard. This was, in a word, to rapidly gather

an army at Corinth, and fling it upon the reckless camp at Pittsburg Landing before Buell's arrival, and, that succeeding,

to march northward in aggressive campaign. The plan was as prompt of adoption as it was bold in conception, and to Corinth

quickly flowed from all directions, troops for the army of invasion. The Gulf States were dredged of their garrisons from

Memphis to Apalachicola, and the trans-Mississippi states, from Missouri to Texas, poured their troops out at Beauregard's

command. Supplies and material, forage and subsistence, were brought on all railroads, while, ordnance lacking, Beauregard

begged their bells of churches and families, and many batteries were cast from the metal so collected.

The concentration of troops began on the first of March. The first process

was to strip the great forts of all their foolish accumulations of troops; for on arriving West, Beauregard had found Columbus

full of troops, and its works built for 14,000. His comment was pointed; "with such a force shut up within a fort, how many

troops do you plan to have outside? Fort Donelson, indefensible, and badly defended, has fallen, as well it might, its works

being, nothing. Unless you have strong works, and troops capable of defending them to the last, it is better not to have forts."

His plan, accordingly, was to withdraw their garrisons from the neighboring forts, leave 2,000 men at one strong point on

the river above Memphis, with provisions enough for sixty days, spread torpedoes, and, with the aid of gun-boats, set these

men to hold the river. All the other works should set free their troops to join in an aggressive movement, and having concentrated

everything, he would take the initiative, and seize a victory. Accordingly, he had ordered Polk to withdraw from Columbus

to Island 10, which had been prepared for his reception. The latter point he designed to hold only till he could prepare Fort

Pillow, still further down, which he had selected as the real river defence of Memphis; and, in fact, it was finished on the

very day when Island 10 was evacuated. Polk's corps of two divisions soon joined Beauregard from Columbus, and Bragg's fine

corps, also of two divisions, came up from Mobile and Pensacola. The latter had been well drilled by that disciplinarian,

and were pronounced the best troops in the Confederacy; though in reality, they were not the superiors of the Virginian army

of Joe Johnston; but those were the early days of the war, when the skirmishes and picket duty around Santa Rosa and Ship

Island, and the threatening of Fort Pickens were supposed to season recruits into veterans. The Governors of Tennessee, Mississippi,

Alabama, and Louisiana were called on for volunteers, and issued at once strenuous alarum-cries, so that in speedy response

their people flocked towards Corinth by regiments, companies, squads, or unarmed and singly. All these were slowly crystallized

into the Army of the Mississippi, and to these Johnston added all his forces, forming Hardee's corps, himself assuming supreme

command, with Beauregard as second.

The march of Buell hastened preparations, but most of the troops were entirely

raw, and hence the army took its shape slowly. Above all, it lacked the appliances of organization; for the Richmond authorities,

usually self-sufficient, narrowminded, and wrong-headed past all belief, in their conduct of affairs, yet went to no such

inconceivable lengths of folly and stupidity, as in their reluctance to organize their armies, and in their jealousy of conferring

such ordinary military rank and such latitude of power as is necessary for the assembling of an army, and the gradation of

its component parts. The first condition Beauregard had made in going West, was a fixed number of troops to fight with, but

these, of course, he did not get, nor any approximation thereto. The second condition was the detail to him of a staff corps,

and some such officers of a higher grade as could aid him in his task of remodelling the Western army. He got that no more

than the other, though both were promised with equal distinctness: his fixed number of colonels and lieutenant-colonels, which

were to have been sent, never came. These necessities were doubly felt when the problem was to assort and mould the fragmentary

bodies of volunteers pouring into Corinth. However, by laying the shoulder to the wheel in steady work, the 1st of April arrived

with some approximation--though a vexatiously imperfect one--to the task undertaken, for the troops were at last in good condition

and very confident. Johnston's forces lay chiefly along the railroad easterly from Corinth to Iuka, northerly from Corinth

to Bethel. Spies and officious people in the region had brought daily and nightly news of the progress of Buell, and the position

of each division's bivouac, and equally minute and positive details were known of Grant's army. When Buell's bridge over Duck

River was built, it was felt that the blow must be struck at once; and when, just before midnight of the 2d of April, a courier

brought news of Buell's rapid stride from Columbia, the advance was instantly ordered. It was already a day later than originally

intended, and then the dispositions for guarding the depots of supplies and the roads around Corinth and Purdy had to be made.

But on the 3d, the remainder of the army, about 40,000 strong, moved straight forward over the practicable roads towards the

river, where, sixteen miles distant, lay Grant's army at Pittsburg Landing. The advance was to march "till within sight of

the enemy's outposts."

Immediately on starting the roads were found in wretched condition, --an evil

augmented by the rawness of the troops in marching. By the night of the 4th, however, the main interval had been passed, and

the troops ordered to attack at dawn of the 5th. The advance cavalry flushed and eager, had already got upon the Union outposts,

and been repulsed by Sherman's advance, for their pains. But, about 2 o'clock on the 5th, a furious rain-storm fell, and continuing

for hours, drenched the whole army as it lay in bivouac, filled the creeks, spoiled the roads, and rendered attack impossible.

In addition, the bad organization delayed the troops from getting into position. Intolerably vexatious as was this loss of

a whole day, it only remained to endure it. The lines were moved up still nearer, till the advance was but three fourths of

a mile from the Union pickets, and but two miles from the main camp. The troops were in three lines, according to the order

of attack. Hardee's corps of two divisions covered the intersection of the Pittsburg and Hamburg roads, with half its cavalry

on either flank, between Owl and Lick creeks; Gladden's brigade of Withers' division of Bragg's corps filling up the space

to the latter stream. Eight hundred yards behind him lay the rest of Bragg's two divisions in the second line. With a little

wider interval, Polk's corps formed the third, and reserve line, with Breckinridge's reserve divisions upon its right and

rear. The roads were cleared, and the attack ordered betimes in the morning; and so passed the eve of Shiloh.

II.

THE BATTLE OF SHILOH.

[First Day - Sunday, April 6, 1862]

The morning of

Sunday, April 6th, broke clear and pleasant after the rains of the days preceding, and found the Union army still peacefully

sleeping in its camps along the Tennessee. The general topography of the rugged plateau, which, seamed with ravines, but mainly

ninety or a hundred feet above the road-bottom, contained the encampment, has already been drawn: it was at once camp and

battle-ground. Its southerly limit is Lick Creek, which, rising, a few miles in the interior, runs between very high banks

easterly to the Tennessee, at right angles with the latter, three miles above the landing. Near its source, Owl Creek, bending

like an arm around the camping-ground, forms the westerly and northerly boundary of the plateau, and emptying into Snake Creek,

joins the Tennessee at right angles, two miles below the Landing. The drift or slope of the land is, in general, from the

bluffs of Lick Creek across to the banks of Owl Creek; but the enclosure is uneven, and lesser rivulets, of course, swell

those already mentioned. The battle-ground is from three to five miles wide, and as much in length. The troops were posted

with reference to the roads from the Landing. The main road winding up the top of the hill, there branches, and the right

hand one leads along the river across Snake Creek to Crump's Landing. Further on, a mile from the Landing, the main road sends

out another branch, this time to the south, up the shore across Lick Creek to Hamburg. Continuing inland, it once more divides,

this time into two roads, both leading to Corinth, of which the one nearest the Hamburg road is called the Ridge road, from

its elevation. Shiloh Church is three miles out from the Landing, on the further road to Corinth, near Owl Creek, and thence

a road runs north-westerly to Purdy. The many cross-roads and interlacing paths need not be described.

The divisions of McClernand, Prentiss, and Sherman, formed the advance line

of Grant's army; those of Hurlburt and W. H. L. Wallace the forces at the Landing. Sherman's division, facing south, covered

the Corinth road at Shiloh Church, with one brigade on each side of the road, and one on the extreme right guarding the bridge

on the Purdy road over Owl Creek; while, detached to the extreme left of the whole army, Sherman had a brigade, under Colonel

Stuart, guarding the Hamburg road at Lick Creek Ford, near the Tennessee. Prentiss, on Sherman's left, was guarding the Ridge

road, facing southerly and south-westerly. McClernand was on Sherman's left and rear, on the Purdy road--his line and Sherman's

forming an acute angle, by the extension of their left wings. Hurlburt and W. H. L. Wallace were back at the bluff near the

Landing, where were all the supplies,--the forage, subsistence, stores, and trains. Lew Wallace lay at Crump's Landing, with

his brigades posted conveniently on the road running thence to Purdy.

Ere the gray of dawn, the advanced line of Johnston's army, composed of Hardee's

corps, strengthened on its right by Gladden's brigade from Bragg's, stealthily crept through the narrow belt of woods, beyond

which all night they had seen their innocent enemy's camp-fires blazing. No fife or drum was allowed; the cavalry bugles sounded

no reveille; but with suppressed voices, the subordinate officers roused their men, for many of whom, indeed, the knowledge

of what was to come, had proved too exciting for sound slumber. Bragg's line as quickly followed, and, in suit, the line of

Polk and Breckinridge.

By one of those undefinable impulses or misgivings which detect the approach

of catastrophe without physical warning of it, it happened that Colonel Peabody, of the 25th Missouri, commanding the first

brigade of Prentiss's division, became convinced that all was not right in front. Very early Sunday morning, therefore, he

sent out three companies of his own regiment and two of Major Powell's 12th Michigan, under Powell's command, to reconnoitre,

and to seize on some advance squads of the enemy, who had been reported flitting about, one and a half miles distant from

camp on the main Corinth road. It was the gray of dawn when they reached the spot indicated; and almost immediately, from

long dense lines of men, coming swiftly through the tall trees, opened a rattling fire of musketry. It was the enemy in force.

The little band fell back in haste, firing as best they might. Close on their heels pressed the whole of Hardee's line, and

enveloping the left of Prentiss's camp, stretched in a broad swathe across to the gap between his division and Sherman's,

and thence onward across Sherman's. Instantly the woods were alive with the rattle of musketry right and left, on front and

flank. The Confederate batteries, galloping up on every practicable road and path, unlimbered in hot haste, and poured their

shot over the head of the infantry in the direction of the tents now faintly gleaming ahead. The startled infantry outposts,

mechanically returning a straggling fire, yielded overborne by the mighty rush of their enemy, and then streamed straight

back to the main camps. The divisions of Sherman, Prentiss, and McClernand started from their peaceful slumbers amid the roar

and smoke of battle. The exultant Confederates, creeping so long with painful reticence, now woke the forests with their fierce,

long-pent yells. The flying pickets served, like avant-couriers to point the way for their pursuers. And thus, with the breaking

light of day, overhung by sulphurous battle-clouds, through which darted the cannon-flash, while the dim smoke curled forward

through every ravine and road, and enveloped the camps, Grant's army woke to the battle of Shiloh.

So rude an awakening might well unnerve veterans, and much more these raw

troops thus thrust invitingly out for attack, many of whom were unused even to loading their own muskets. But instantly, from

all the tents, amid the long-roll of drums, the quick cries of "turn out," and "fall in," from company-officers and sergeants,

the rapid rollcalls of the orderlies, the clink of rammer and gunstock, the orders mingling everywhere, in all tones, from

officers of all grades, the astounded troops of Sherman, Prentiss, and McClernand hurried half dressed into line; while commanders

were hastily fastening on swords, or mounting horses, and aids were flying back to rouse the men of Hurlbut and Wallace in

the rear.

At the height of the shouting, the forming of the troops, the spurring hither

and thither of the aids, the fastening of belts and boxes, and the dressing of the laggards, the enemy's advance with loud

yells swept through the intervening forest, and burst upon the camps.

It was now about 7 o'clock, and the resistance of the Union picket line, feeble

as it necessarily was, had been of priceless service in gaining time, while the rough and impracticable interval over which

the Confederates had to pass served to breakup somewhat as well as to extend and thin their lines. There seems to have been

no special tactical formation, nor any massing of men on a key-point--the key-point, if any there was, had not been discovered.

The movement in short, was predicated on a surprise, and the method, to fling the three corps-deep lines of the Army of the

Mississippi straight against the Union army from creek to creek; to "drive it back into the Tennessee." As for the Union generals,

overwhelmed with surprise and chagrin, they could only strike back where the enemy struck, seeking above all to save the camps.

Such was the nature of the confused, irregular, but bloody series of conflicts, which now raged for three hours, during which

time the Union troops succumbed, and yielded the first breadth of debatable ground.

Prentiss' division occupied the Union left (except for the detached brigade

of Stuart), and covered the Corinth ridge road. Against him rushed Hardee's right and Gladden's brigade, but it was a full

hour before the outposts of Peabody's brigade had been driven back into Prentiss' camps. By that time Prentiss had his line

hastily formed. About 7 o'clock, Gladden moved upon Prentiss' centre, and soon the roar of artillery and musketry on both

sides proclaimed general battle. Meanwhile, Hardee's line having been protracted and divided all along the Union front, Bragg

threw the second line by detachments, into the gaps, to reinforce it. Before half past seven o'clock, therefore, Bragg's line

had moved up, and was fighting, intermingled with Hardee's. Now the right of Bragg's two divisions was the division of Withers,

one brigade of which, Gladden's, had the night before been put into the first line, on Hardee's right. The whole three brigades

were now fighting together against Prentiss' division. Chalmers' brigade swept around to Prentiss' left flank; Gladden's pushed

at his centre, and Jackson's struck his left, and began to pour through the gap between Prentiss and Sherman. The batteries

on both sides being run to the front, plowed through the opposing ranks; Gladden was struck by a cannon shot and mortally

wounded, charging at the head of his brigade; Peabody was mortally wounded in the Union lines. The Confederates pressed on,

gaining little by little on either flank, till the fire from their three batteries, as well as the infantry fire of their

three brigades began to cross in Prentiss' lines. Regiments gave ground here and there, now on the left, now on the right,

now in front, and before nine o'clock, the Confederates having driven Prentiss from all his camps, were masters of the field.

The camps were quickly despoiled, accoutrements, clothing, rations just cooked, and plunder of all sorts even, seized. With

difficulty the officers drew their men together, and Withers's triumphant division was re-formed, to move once more on the

new line of the Union left.

Simultaneously, Hardee's centre and left had been attacking the Union right,

or the division of Sherman, whose line ran across the other Corinth road. The centre was at Shiloh Church, and Sherman had

put two batteries there, those of Taylor and Waterhouse, and two brigades, Hildebrand's on the left of the road, and Buckland's

on the right. On the right of Buckland was McDowell's brigade, with Behr's battery on the right and rear, on the Purdy road.

McClernand, just in rear of Sherman, had promptly sent three regiments to the support of Hildebrand, on Sherman's left, and

three batteries soon after moved over. By seven o'clock, the Confederate advance showed through the woods, and opened a stragggling

fire.

Half an hour later, the whole Confederate force was up; the three brigades

of Hardee's corps--Hindman's, Cleburne's, and Wood's, formed the right of the line which burst upon Sherman. Bragg's original

second line of two divisions had already been separated, as we have seen, and the right one, Withers's, thrown against Prentiss.

His left division, that of Ruggles, was formed on Hardee's left, its three brigades being Gibson's, Anderson's, and Pond's.

Before eight o'clock, the battle was raging with fury at all points; for,

in dogged determination to drive their foe to the river, the line of Confederate advance was determined simply by what might

yield to their onset. For an hour the contest was severe, the Union batteries being well posted and extremely well served,

and inflicting grievous punishment upon the Confederates, whenever the latter appeared from the cover. Sherman himself was

indefatigable in remedying the misfortunes of the surprise; he moved in every part of the field, attended personally to the

fire of batteries, held up raw regiments to their task, and, long before noon, became the central figure on the Union side

at Shiloh. Towards his left, when Hindman, Cleburne, and Wood gradually passed in between himself and Prentiss, and swung

upon his left flank, the firing was so hot (for Sherman clung to this point with bull-dog, tenacity, regarding it as the key-point

to his position) that Bragg threw Gibson's brigade of Ruggles's division across to Hindman's support. Sherman's batteries,

however, tore this column badly while it marched across by the right flank to its new position; the other two brigades of

Ruggles, those of Anderson and Pond, remained and attacked Sherman's right, under McDowell. Polk's third, or reserve line

was not long kept from the contest. Three regiments, and several batteries from McClernand, and four regiments from Hurlburt

had early arrived on Sherman's left, and enabled him to withstand the Confederate attack there. Seeing this heavy reinforcement

at an important point, Johnston, who had ridden to the front, and who, according to Polk, at once showed "the ardor and energy

of a true soldier," and promised victory in "the vigor with which he pressed forward his troops"--Johnston himself called

on Polk for a brigade to support the right. Stewart's brigade of Clark's division was given to him, and he took it in person.

Beauregard next demanded a brigade for the left to help Ruggles, and Cheatham led one to that point. Finally, Polk threw his

two remaining brigades against Sherman's centre. The Confederate troops, being now all in action, soon served Sherman as they

were serving Prentiss. The latter, at nine o'clock, had been driven from his camps, and the brigade of Polk's corps, which

Johnston led into the gap between Prentiss and Sherman, completely turned the latter's left flank. The rush which finally

broke Prentiss, also broke up Hildebrand, and his two left regiments fell back in great disorder and disappeared from the

field." Instantly the Confederates swooped upon Waterhouse's battery, and Sherman's left was turned. He gallantly clung a

little longer to Shiloh Church, and held up McDowell and Buckland, together with the two brigades sent from McClernand's division.

Polk's two brigades, however, now moved up, and, with those of Anderson and Pond, attacked the two Union divisions, and carried

Behr's battery in an instant. Meanwhile, the Confederates hurried their artillery down along the brook in the gap on Sherman's

left and rear, and routed his troops with an enfilading fire. Sherman then fell back, and, before ten o'clock, had surrendered

his whole camp. General Polk says that the forces of Sherman and McClernand immediately opposed to him, "fought with determined

courage, and contested every inch of ground," and that "the resistance at this point was as stubborn as at any other on the

field."

We have now, at ten o'clock, reached a sort of epoch in the battle. The first

onset of the Confederates has been successful, and the divisions of Sherman and Prentiss, supported in part by those of Hurlburt

and W. H. L. Wallace, have been driven from their camps. There was neither at this time nor later, any positive lull in the

battle; but the retreat of the Union forces caused the taking up of a new and concentrated line, and a portion of the Confederates

paused in unsoldierly fashion for plundering the captured camps, before they essayed the sequel of their task. Sherman, on

losing his camps and two batteries, had two brigades left to work with, McDowell's and Buckland's, and Taylor's battery. As

for Hildebrand's brigade, they had mostly long since fled, and were running towards the Tennessee, on whose banks an immense

throng of fugitives from the various divisions, in detachments of all sizes from regiments down to groups of fours, was already

collecting, and swelling each hour. Sherman's remaining troops retreated to McClernand's right, where they were halted, and

got in hand to renew the contest. The Union line was so confused and irregular thenceforth, and so constantly swaying and

shifting, that it would be uninstructive as well as uncandid, to pretend to draw it in detail. In general, however, Sherman's

residue of troops was on the right; next, McClernand's division; next, Wallace's; next (after recovering), Prentiss's; next,

Hurlburt's; finally, Stuart's detached brigade of Sherman's division. A word will explain how this disposition was reached.

The stress of the opening attack on Prentiss and Sherman was very naturally along the two Corinth roads across which they

lay. Between the roads was an unguarded interval, into which the Confederates had passed, and by which they had flanked both

divisions. McClernand, Hurlburt and Wallace had instantly moved up to relieve the stress on this worst point--which supposing

we assign to the first Union positions the dignity of a line,--would be called the centre. There they substantially remained,

receiving the shock of battle as they came up--McClernand first, because nearest, and the others quickly after. Sherman, on

being driven back, had naturally fallen on the right of McClernand, so as not to impede his fire. McClernand had moved forward

in detachments, as we have seen, to Sherman's left, in instant answer to an urgent call for help. Now, by the abandonment

of the camps two advance divisions, he was stoutly holding his own, having swung around so as to face nearly south-east, on

the main Corinth road. Wallace's shortest road up from the landing brought him to the left of McClernand, where he arrived

in time to receive the direct impact of the dense column pouring down the Corinth road after turning Prentiss out of his tents.

Hurlburt, at 7 1/2 o'clock, had received a message from Sherman that "he was already attacked in force, heavily upon his left."

We have seen that the main battle began about seven. Hurlburt within ten minutes had Veatch's brigade on the march to Sherman's

left, where it soon arrived, and went into action, together with the column from McClernand. In the new alignment it became

separated, half being formed on MeClernand's right, and half on his left. A few minutes later, came similar tidings from Prentiss,

and Hurlburt then took forward his two remaining brigades, those of Williams and Laumann. He marched to the rear and left

of Prentiss, and met an appalling sight. "His regiments drifted through my advance," Prentiss gallantly striving, but in vain,

to rally them. Fortunately, Hurlburt's men were not broken up by this perforation of their columns, and their line was rapidly

formed. Behind Hurlburt, Prentiss "succeeded in rallying a considerable portion of his command," and then, says the former,

"I permitted him to pass to the front of the right of my third brigade, when they redeemed their honor."

Stuart's brigade, or what was left of it, for he had suffered like Sherman

and Prentiss from the independent volition of some subordinates, in moving their commands to the rear--was on Hurlburt's left.

Weeks before, when this whole camping-ground had been occupied with a view to moving on Corinth, Sherman had stretched his

command over the front, along Owl and Lick creeks,--a space of three or four miles, the other divisions being placed as already

indicated, in quasi support. Stuart, accordingly, was off on the left on the Hamburg road, which crosses Lick Creek near the

Tennessee. At 7 1/2 o'clock he had received from Prentiss a verbal message like that sent to Hurlburt. "In a very short time,"

he adds, "I discovered the pelican flag advancing in the rear of General Prentiss's head-quarters." So quickly was the latter

officer's camp turned on the left. Stuart formed his three regiments, and, in answer to a request, Hurlburt in fifteen minutes

had a battery and a regiment in the long interval between Stuart and Prentiss. Half an hour elapsed, during which the enemy

got a battery in a commanding position, and opened a fire of shells on Stuart's camp. Before long, the Confederates began

to move across upon him from Prentiss's left and against his other flank. The ground is the highest on the whole field, and

defensible by a small force. Riding to the right, Stuart found that "the battery had left without firing a gun, and the battalion

on its right had disappeared." Riding to the left, he found his own regiment there had also departed, as he was told, to "a

ridge of ground very defensible for infantry" in the rear. "But," he expressively adds, "I could not find them, and had no

intimation as to where they had gone." Several hours later, it is pleasant to know, that his search was rewarded, by discovering

"seventeen or eighteen men" of this force, who, under the adjutant, joined him.

For five hours, now, the battle went confusedly on. Its general tenor was

the forcing back of the Union troops more or less slowly to the landing. Had the terrain been other than it was, the

result might have been more quickly accomplished. But rolling and wooded, cleft and cut up by ravines, with here and there

a commanding and defensible ridge but no salient positions, it afforded opportunity for protracted, irregular, and severe

fighting. Both in attack and defence it threw upon subordinate officers the care of their own commands. It prevented also

the decision of the day by a stroke on either side, and neither a blow nor a counter-blow was of necessity fatal. In this

irregular and fragmentary fighting, however, the chief brunt fell upon Wallace, McClernand, and Hurlburt,--not only because

the divisions of the two former had had the experience of Donelson, while the other three divisions were mostly raw, but also

because the troops of Sherman and Prentiss had become disorganized and used up by the morning's surprise. General Grant came

upon the field as soon as he could arrive from Savannah, where he had heard the roar of battle. It took a considerable time

to reach the Landing, but not long afterwards to ride to the point to which his troops had been driven from their camps.

The Confederate lines had, meanwhile, been not much less confused than those

of their enemy. They had advanced with three lines of battle and a reserve; in two hours they had thrown everything in, by

divisions, brigades, or even regiments, just where it happened to be wanted. As some of the Union divisions had at times portions

of three or four divisions under their control in the confused disorganization, so it was precisely with the Confederate corps

commanders. Polk's corps was divided from one end of the line to the other. At length, he sought out General Bragg, and it

was arranged that Bragg henceforth should take charge of the right, Polk of the centre, and Hardee of the left, independent

of former dispositions. This was at half past ten o'clock, and the commands so continued thenceforth through the day. From

that time till three the conflict went on with vigor. The Confederate leaders now positioned troops, now encouraged them,

now personally led them. The right of the Confederate line under Breckinridge had for several hours a long and obstinate contest

with Hurlburt, aided by Prentiss. But the Union centre, held by Wallace, and the left by McClernand, were especially aimed

at by the Confederates, in order to cut their way through to the Landing. Here was the Confederate centre, which has been

described as flanking Sherman on the left and Prentiss on the right,--Hardee's line, with the brigades of Hindman, Cleburne,

and Wood, three brigades of Polk's corps, under Cheatham, and Gibson's brigade of Ruggles's division. Bragg and Polk again

and again tried to force this position. Wallace had the three batteries of Cavender's battalion well posted on commanding

ridges and well served, and his infantry behaved well. McClernand did the same for his three batteries, those of Schwartz,

Dresser, and McAllister. Under Wallace's vigorous command, Bragg's efforts long failed. On the left, however, Polk and Hardee,

attacking with the brigades of Pond and Anderson, and a portion of the centre, had already found easier work. Sherman's disordered

line in that quarter could with difficulty be recovered from the shock of the morning. It was formed of parts of Buckland's

and McDowell's brigades. The former officer says that, in forming line again on the Purdy road, "the fleeing mass from the

left broke through our lines, and many of our men caught the infection and fled with the crowd." One regiment, Cockerill's,

was kept in something like organization; but as to the rest, "we made every effort to rally our men, with but poor success.

They had become scattered in every direction." The Confederates accordingly turned the Union right, and possessed themselves

of McClernand's camps, and half the guns of his three batteries. McClernand and the rest of Sherman fell back to the right

of Wallace, who still held fast to his camp near the Landing.

So far as the Confederates had a tactical plan now, it was to turn the Union

left, and, sweeping along the bank, capture their base at the Landing, and drive them down the river. On the Confederate right,

opposite Hurlburt and Stuart, were the divisions of Breckinridge, Withers, and Cheatham, under the direction of Johnston himself,

who, energetic and determined, was exerting his personal influence with his men. The Confederate General became frequently

exposed to the hot fire of artillery and musketry rolling from Hurlburt's line. One of the latter's batteries, indeed, had

been instantly abandoned by its officers and men, as he says, "with the common impulse of disgraceful cowardice." The other

two, however, had an effective fire from commanding positions, while several of his infantry regiments exhausted their ammunition

for a time. For a time the Confederates made tremendous charges against this position, and, amid the hot fire which was returned,

about two o'clock a ball struck Johnston as he sat on his horse, eagerly regarding the movement. He refused to notice it,

and gave orders as before; but it was the death-wound. Governor Harris, his volunteer aid, riding up, found him reeling in

the saddle. "Are you hurt?" "Yes, I fear mortally." And, with these words, stretching out his arms, he fell upon his companion,

and a few minutes later expired.

Of the military character of Sydney Johnston, it is difficult to speak with

surety. He has certainly left a great fame; but this probably has its foundation rather in what was anticipated of him than

in what he achieved. He was a man of a high order of character, just, generous, chivalrous, and brave. He had an eminent administrative

faculty, and Davis highly regarded his political talent. But it is doubtful whether he would have risen to the rank of such

men as Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, or Jackson. His manner of defending the frontier committed to him was very faulty, and the

readiness with which he followed the suggestions of Beauregard shows that he had but little power of initiative and but slight

appreciation of grand war.

It was now three o'clock, and the battle was at its height. Dissatisfied with

his reception by Wallace, on the Corinth road, Bragg, on hearing of Johnston's fall, on the right, determined to move round

thither and try his success anew. He gathered up the three divisions already spoken of, and, with specific orders of attack,

flung them against Hurlburt, Stuart, and Prentiss. The assault was irresistible, and the whole left of the Union position

giving way, Bragg's column drove Stuart and Hurlburt to the Landing, swept through Hurlburt's camp, pillaging it like those

of Prentiss, Sherman, Stuart, and McClernand. Simultaneously, Polk and Hardee, rolling in from the Confederate left, forced

back the Union right, and drove all Wallace's division, with what was left of Sherman, back to the Landing,--the brave W.

H. L. Wallace falling, in breasting this whelming flood. Swooping over the field, right and left, the Confederates gathered

up entire the remainder of Prentiss's division about 3000 in number--with that officer himself, and hurried them triumphantly

to Corinth.

At five o'clock the fate of the Union army was extremely critical. Its enemy

had driven it by persistent fighting out of five camps, and for miles over every ridge and across every road, stream, and

ravine, in its chosen camping-ground. Full 3000 prisoners and many wounded were left in his hands, and a great part of the

artillery with much other spoils, to grace his triumph. Bragg's order, "Forward, let every order be forward;" Beauregard's

order, "Forward boys, and drive them into the Tennessee," had been filled almost to the letter, since near at hand rolled

the river, with no transportation for reinforcements or for retreat. Before, an enemy flushed with conquest, called on their

leaders for the coup de grace. What can be done with the Union troops? Surely the being at bay will give desperation.

Unhappily the whole army greatly disorganized all day, was now an absolute wreck; and such broken regiments and disordered

battalions as attempted to rally at the Landing, often found the officers gone on whom they were wont to rely. Not the divisions

alone but the brigades, the regiments, the companies, were mixed up in hopeless confusion, and it was only a heterogeneous

mass of hot and exhausted men, with or without guns as might be, that converged on the riverbank. The fugitives covered the

shore down as far as Crump's, where guards were at length posted to try to catch some of them and drive them back. The constant

"disappearance," as the generals have it, of regiments and parts of regiments since morning, added to thousands of individual

movements to the rear, had swarmed the Landing with troops enough--enough in numbers--to have driven the enemy back to Corinth.

Their words were singularly uniform--"We are all cut to pieces." General Grant says he had a dozen officers arrested for cowardice

on the first day's battle. General Rousseau speaks of "10,000 fugitives, who lined the banks of the river and filled the woods

adjacent to the Landing." General Buell, before the final disaster, found at the Landing, stragglers by "whole companies and

almost regiments; and at the Landing the bank swarmed with a confused mass of men of various regiments. There could not have

been less than 4000 or 5000. Late in the day it became much greater." At five o'clock "the throng of disorganized and demoralized

troops increased continually by fresh fugitives," and intermingled "were great numbers of teams, all striving to get as near

as possible to the river. With few exceptions, all efforts to form the troops and move them forward to the fight utterly failed."

Nelson says, "I found cowering under the river-bank, when I crossed, from 7000 to 10,000 men, frantic with fright, and utterly

demoralized." Of the troops lately driven back, he expressed the want of organization by saying the last position "formed

a semicircle of artillery totally unsupported by infantry, whose fire was the only check to the audacious approach of the

enemy." Even this was not all. The Confederates sweeping the whole field down to the bluff above the Landing, were already

almost upon the latter point. Such was the outlook for the gallant fragments of the Union army at 5 o'clock on Sunday.

But Grant's star was fixed in the ascendant. It chanced that the Confederates,

by sweeping away Prentiss on the Union left, had been thrown chiefly towards the southerly side of the Landing. Now, at that

point, as has been described, intervenes a precipitous wooded ravine, "deep, and impassable for artillery or cavalry," says

General Grant, "and very difficult for infantry." And it was precisely here, that, as that commander explains, "a desperate

effort was made by the enemy to turn our left and get possession of the landing, transports, etc." A hard task, therefore,

was set the Confederates at the end of their day's toil. In addition, the Union gun-boats now reinforced the troops, and at

half past five furiously raked the hostile lines which had drawn towards the Landing. The moral effect of these shells on

both the armies, was even greater, as so often at that stage of the war, than the physical. A third piece of fortune favored

the Union armies. It chanced that, on the bluff, had been deposited and parked many siege guns, with heavy ordnance of various

sorts, designed as a part of the train for that future move upon Corinth, which to-day had been so unexpectedly barred. No

artillerists, of course, had yet been prepared for the guns; but Colonel Webster, of General Grant's staff, energetically

called for volunteers to get these pieces into position and essay work with them; and plenty of cannoneers he found whose

field artillery had been captured during the day.

As the fragments of light batteries came galloping in, these were ranged with

the heavy guns, and, in short, a formidable semicircle of forty or fifty guns, or more, of all sizes, soon girdled the Landing,

along the brow of the ravine, which formed an excellent defence. This latter, indeed, stretched far beyond the bluff, and

winding around, continued its protection quite to the Corinth road, the guns dotting its edge, all along. On the right of

the guns all effort was made to disentangle the army that had rushed pell-mell in that direction, while, on the left, the

gun-boats partly covered the artillery position.

At this crisis, also, and to assure the fortune of the army so lately trembling

in the balance, Buell's advance rushed with loud cheers upon the scene. It was Nelson's division, which had arrived thirty

hours before at General Grant's head-quarters, but, finding no transportation ready, had been kept all day from the battle.

But, stimulated by the ever-nearing roar of battle, Nelson's men had hurried along the overflowed roads of the west bank,

and Buell, finding the artillery-wheels sticking hub-deep in mire, had authorized Nelson to drop his trains and push on. So,

by effort and expedient, Nelson got up the river, was ferried across, and his well-drilled men, disregarding what they saw

and heard, rushed spiritedly to the front, and Ammen's brigade deployed in support of the artillery at the point of danger.

The glad news of reinforcement spread like wildfire in the driven army.

Already now, the Confederates were surging and recoiling in a desperate series

of final charges. Warned by the descending sun to do quickly what remained to be done, they threw forward everything to the

attempt. Their batteries, run to the front, crowned the inferior crest of the ravine, and opened a defiant fire from ridge

to ridge, and threw shells even across the river into the woods on the other bank. Their infantry, wasted by the day's slaughter,

had become almost disorganized by the plunder of the last two Union camps, and a fatal loss of time ensued while their officers

pulled them out from the spoils. The men, still spirited, gazed somewhat aghast at the gun-crowned slope above them, whence

Webster's artillery thundered across the ravine, while their right flank was swept by broadsides of 8-inch shells from the

Lexington and Tyler. "Forward" was the word throughout the Confederate line. Bragg held the right, on the southerly slope

of the ravine, extending near the river, but prevented from reaching it by the gun-boat fire; Polk the centre, nearer the

head of the ravine; while Hardee carried the left beyond the Corinth road. At the latter point, the line was half a mile from

the water, and four hundred yards from the artillery on the bluffs. There were few organizations even of regiments, on the

Union side, but a straggling line from Wallace's and other commands, voluntarily rallying near the guns, was already opening

an independent but annoying fire: and these resolute soldiers were as safe as the torrent of fugitives incessantly pouring

down to the Landing, among whom the Confederate shells were bursting. Again and again, through the fire of the artillery,

the gun-boats and Ammen's fresh brigade and the severe flanking fire of troops rallying on the Union right, the Confederates

streamed down the ravine and clambered up the dense thickets on the other slope. Again and again they were repulsed with perfect

ease, and amid great loss; for besides their natural exhaustion, the commands had been so broken up by the victory of the

day and by the scramble for the spoils, that while some brigades were forming others were charging, and there was no concerted

attack, but only spontaneous rushes by subdivisions, speedily checked by flank fire. And, when once some of Breckenridge's

troops, on the right, did nearly turn the artillery position, so that some of the gunners abandoned their pieces, Ammen, who

had just deployed, again and finally drove the assailants down the slope.

Confident still, flushed with past success, and observing the Union dÚdÔle

behind the artillery, Bragg and Polk urged a fresh and more compact assault, on the ground that the nearer they drew to the

Union position, the less perilous were the siege guns and gun-boats. But the commander-in-chief had been struck down, and

Beauregard, succeeding to supreme responsibility, decided otherwise. Bitterly then he recalled the lack of discipline and

organization in his army, entailed by the jealousy and ill-timed punctiliousness of Richmond. Victory itself had fatally disordered

his lines, and the last hard task of assault had thrown them back in confusion from the almost impregnable position. Better

to withdraw with victory than hazard final defeat; for already the sun was in the horizon, and the musket-flashes lit up the

woods. The troops were all intermingled, and several brigade commanders had been encountered by the general, who did not know

where their brigades were. Since darkness already threatened to leave the army in dense thickets under the enemy's murderous

fire, all that was left of the day would be required in withdrawing so disorganized a force. Buell could not have got more

than one division along those miry roads to the river. It was a day's work well done: to-morrow should be sealed what had

auspiciously begun. Thus reasoning, Beauregard called off the troops just as they were starting on another charge, and ordered

them out of range. Then night and rain fell on the field of Shiloh.

[Second Day - Monday, April 7, 1862]

Next morning,

the astounded Confederates beheld a fresh enemy in the lines whence they had expelled a former the day preceding. Surely the

Union host was hydra-like, with a new and deadlier crest springing on the trunk from which the other had been shorn: or like

the mystic wrestler who rose refreshed from mother-earth, whenever he was flung there, spent and bleeding. The new foe was

the army of Buell; and as Beauregard caught sight of its handsomely deployed columns, he instantly felt that in counting on

possible tardiness or want of skill in its commander, he had reckoned without his host. Buell, so soon as his restless troops

could be thrown across Duck river, had (though unsuspicious of the need) driven them on with such soldierly celerity to Savannah

that, had the attack of Beauregard been expected and prepared for, Nelson's division was in season to have been posted far

out in the woods at Shiloh Church; for they were at Grant's head-quarters eighteen hours before the battle. With like energy,

Buell at the first roar of battle had despatched couriers to all his other divisions to drop their trains and move up by forced

marches; so that, on Monday morning, three divisions and three batteries were present to redeem the lost laurels of Sunday.

Lew Wallace's division, too, was up from Crump's Landing. Hearing, the guns on Sunday at Shiloh, he drew up his troops to

march, and impatiently awaited the orders, which, in effect, came at 11 1/2 o'clock, bidding him push over to Snake Creek,

cross it, and form on the Union right. Quickly his troops were off, but on the road they met three officers of Grant's staff,

who were travelling that way. For Wallace they brought no orders, but they did bring such vivid tidings of the day's disaster

and gloom, that Wallace learned that what was once the Union right was now in the Confederate rear. Instantly halting, he

retraced his steps, crossed Snake Creek by the river road, nearer the Landing, and arrived at nightfall, after the battle

was over.

What with the arrival of Buell's troops and Lew Wallace's, and the untying,

from its almost Gordian knot of the army of Grant, there was a busy stir on Monday morning. Of Grant's forces, after eliminating

the dead who lay on the field, the wounded who all night lay there, still more pitiable, and the hopelessly fugitive, there

was still a respectable remainder; and the batteries were assorted and patched, and the artillerists rallied, for of these

there were more than enough for the guns. As for the Confederate army, it rose from bivouac in sorry plight, and the day's

work obvious before them was not of a sort to freshen their spirits. At least, however, Beauregard had fulfilled his promise

to "sleep in the enemy's camp," for his lines were in those of Prentiss, McClernand, and Sherman, and the latter's head-quarters

had been usurped by Beauregard. But it was an uneasy slumber they had seized, in camps hardly worth the winning; for throughout