|

"Bloody Bill" Anderson History

Civil War Missouri and Quantrill's Raiders

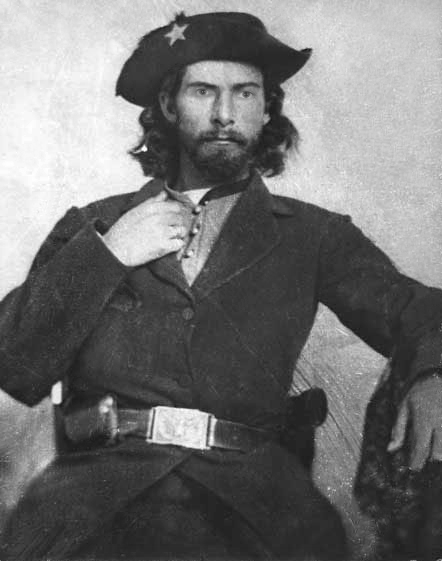

"Bloody Bill" Anderson

A Civil War Missouri Partisan Ranger

As a Confederate Partisan during the Civil War, “Bloody Bill” Anderson was one of the most

notorious members of William "Quantrill's Raiders," which included the likes of Frank and Jesse James, and James and Cole

Younger (later forming the James Younger Gang).

| Bloody Bill Anderson |

|

| Bloody Bill Anderson History (1863-1864) |

"Bloody Bill" Anderson: A Civil War History

Introduction

William T. Anderson (1839 – October 26, 1864), better known as "Bloody

Bill," was one of the deadliest and most brutal pro-Confederate guerrilla leaders in the American

Civil War. Anderson led a band of Missouri Partisan rangers* that targeted Union loyalists and Federal soldiers

in Missouri and Kansas.

Raised by a family of Southerners in Kansas, Anderson began supporting himself

by stealing and selling horses in 1862. After his father was killed by a Union-loyalist judge, Anderson fled Kansas for Missouri.

There, he robbed travelers and killed several Union soldiers. In early 1863, Anderson joined Quantrill's Raiders, a pro-Confederate group of guerrillas that operated in Missouri. (See Missouri Civil War History.) He became skilled at guerrilla warfare, earning the trust of the group's leaders, William Quantrill and George

M. Todd. Anderson's acts as a guerrilla led the Union to imprison his sisters; after one of them died

in custody, Anderson devoted himself to revenge. He took a leading role in the Lawrence Massacre, and later participated in

the Battle of Fort Blair.

In late 1863, while Quantrill's Raiders

spent the winter in Texas, animosity developed between Anderson and Quantrill. Anderson, perhaps falsely, implicated

Quantrill in a murder, leading to the latter's arrest by Confederate authorities. Anderson subsequently returned to Missouri

as the leader of a group of raiders and became the most feared guerrilla in the state, killing and robbing dozens of Union

soldiers and civilian sympathizers throughout central Missouri. Although Union supporters viewed him as incorrigibly evil,

Confederate sympathizers in Missouri saw his actions as justified, possibly owing to their mistreatment by Union forces. In

September 1864, he led a raid on Centralia, Missouri. Unexpectedly, they were able to capture a passenger train, the first

time Confederate guerrillas had done so. In what became known as the Centralia Massacre, possibly the war's deadliest and

most brutal guerrilla action, his men killed 24 Union soldiers on the train and set an ambush later that day that killed more

than 100 Union militiamen. A month later, Anderson was killed in battle.

Historians have made disparate appraisals of Anderson: some see him as a

sadistic, psychopathic killer, but for others, his actions can not be separated from the general lawlessness of the time.

| Bloody Bill Anderson Civil War History |

|

| Bloody Bill Anderson and Quantrill's Raiders |

| Bloody Bill Anderson |

|

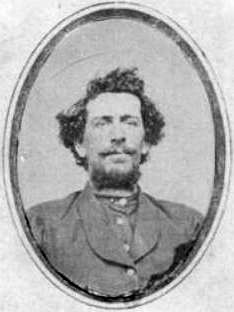

| William T. Anderson, aka Bloody Bill Anderson (1864) |

Quantrill's Raiders

Missouri had a large Union presence throughout the Civil War, but also many

civilians whose sympathies lay with the Confederacy. From July 1861 until the end of the war, the state suffered up to 25,000

deaths from guerrilla warfare, more than any other state. Confederate General Sterling Price failed to gain control of Missouri

in his 1861 offensive and retreated into Arkansas, leaving only the guerrillas to challenge Union dominance. Quantrill was

at the time the most prominent guerrilla in the Kansas–Missouri area. (Border State Civil War History.)In early 1863, William and Jim Anderson traveled to Jackson County, Missouri,

to join him. William Anderson was initially given a chilly reception from other raiders, who perceived him to be brash and

overconfident.

In May 1863, Anderson joined members of Quantrill's Raiders on a foray near Council Grove, in which they robbed a store 15 miles (24

km) west of the town. After the robbery, the group was intercepted by a United States Marshal accompanied

by a large posse, about 150 miles (240 km) from the Kansas–Missouri border. In the resulting skirmish, several raiders

were captured or killed and the rest of the guerrillas, including Anderson, split into small groups to return to Missouri.

Castel and Goodrich speculated that this raid may have given Quantrill the idea of a launching an attack deep in Kansas, as

it demonstrated that the state's border was poorly defended and that guerrillas could travel deep within the state before

Union forces were alerted. (See also Kansas Civil War History.)

In early summer 1863, Anderson was assigned the rank of lieutenant,

serving in a unit led by George M. Todd. In June and July, Anderson took part in several raids that killed Union soldiers,

in Westport, Kansas City, and Lafayette County, Missouri. The first reference to Anderson in Official Records of the American

Civil War concerns his activities at this time, describing him as the captain of a band of guerrillas. He commanded 30–40

men, one of whom was Archie Clement, an 18-year-old with a predilection for torture and mutilation who was loyal only to Anderson.

By late July, Anderson led groups of guerrillas on raids, and was often pursued by Union volunteer cavalry. Anderson was under

Quantrill's command, but independently organized some attacks.

| Bloody Bill Anderson and Civil War Missouri Map |

|

| Missouri and Quantrill's Raiders Map |

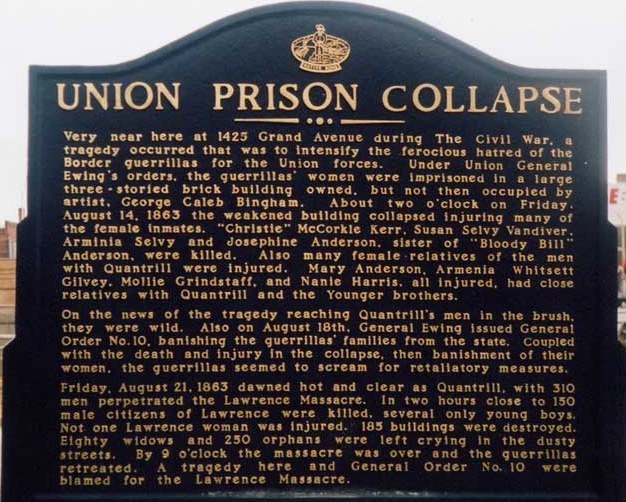

Quantrill's Raiders had a support network in Jefferson County, Missouri,

that provided them with numerous hiding places. Anderson's sisters aided the guerrillas by gathering information inside Union

territory. In August 1863, however, Union General Thomas Ewing, Jr., attempted to thwart the guerrillas by arresting their

female relatives, and Anderson's sisters were confined in a three-story building on Grand Avenue in Kansas City with a number

of other girls. While they were confined, the building collapsed, killing one of Anderson's sisters. In the aftermath, rumors

that the building had been intentionally sabotaged by Union soldiers spread quickly; Anderson was convinced that it had been

a deliberate act. Biographer Larry Wood wrote that Anderson's motivation shifted after the death of his sister, arguing that

killing then became his focus—and an enjoyable act. Castel and Goodrich maintain that killing became more than a means

to an end at that point for Anderson: it became an end in itself.

Regarding Quantrill's Raiders (which included many Ruffians), in the Official Records, Union Lieutenant Colonel Dan M. Draper reported to

Brigadier General Fisk on September 29, 1864, the following descriptive battle report for what is commonly

known as the Centralia Massacre:

"After leaving Centralia on Tuesday the guerrillas fell back about two miles

to the timber, keeping pickets in view of the town. Major Johnston was then following their trail with 150 men. He went to

where they were, and when he came in sight dismounted his men and were moving toward him, but checked up at this, but soon

came on a charge. When 150 yards distant the major ordered his men to fire, came on, and when within 100 yards the men began

to break, many of them not firing the second shot, and none of them more than that. It then became a scene of murder and outrage

at which the heart sickens. Most of them were beaten over the head, seventeen of them were scalped, and one man had his privates

cut off and placed in his mouth. Every man was shot in the head. One man had his nose cut off. One hundred and fifty dead

bodies have been found, including the twenty-four taken from the train.

I endeavored in every way to find out their whereabouts,

but have not been able to hear of them since they went into that country. ["Bloody Bill"] Anderson was at least thirty hours

ahead of me when I got to Centralia, and I knew he must turn back or cross the river before I could get to him. I came back

here, after ordering the citizens to bury the eighty-five bodies left at Centralia, as this was the best point at which to

get information from the country. Colonel Stauber sent out scouts this afternoon, which have not yet returned, to ascertain

the cause of firing heard by citizens of the country south of this. The party has orders not to fight but get information.

As soon as it returns I will give results. Dan M. Draper, Lieutenant-Colonel."

Official

Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 41, Part 1, pp. 440-441.

| Bloody Bill Anderson |

|

| Bloody Bill Anderson, Missouri History |

Death

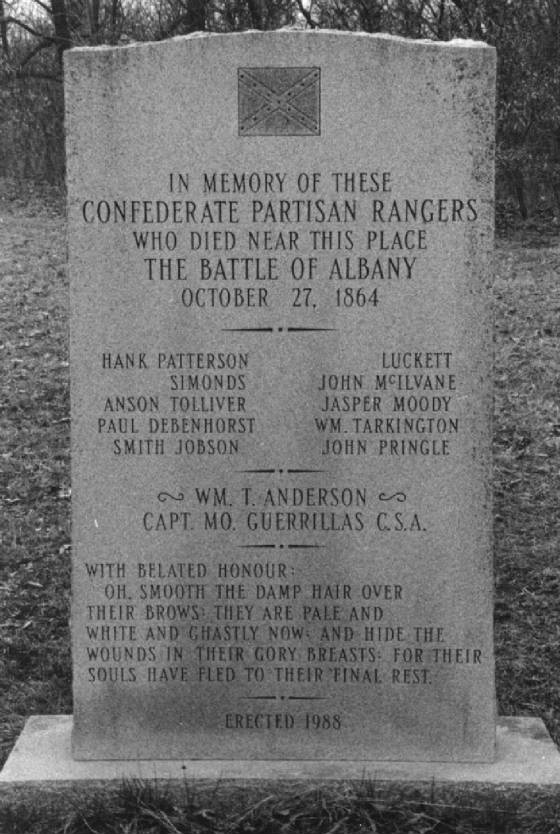

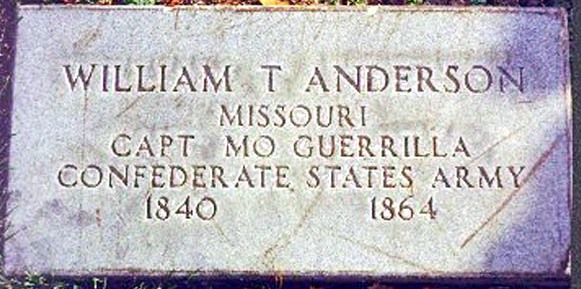

On October 26, 1864, Anderson’s Partisan rangers, approximately

150 men, battled Union troops near Orrick, MO. Anderson and his men charged Union forces, killing five or six of them,

only to be repulsed under heavy fire. After their fellow Partisans retreated, Anderson and one other man, the son of a Confederate

general, however, continued to charge. During the charge, Anderson was struck by a bullet, likely killing him instantly. Four

other guerrillas were killed in the attack. The well-known “Bloody Bill”

Anderson was buried at Pioneer Cemetery in Richmond, Missouri.

A Union colonel, Samuel P. Cox, wrote the following account regarding the final moments of Anderson:

"Notorious bushwhacker, William T. Anderson and his fiendish gang, near Albany, raised the Indian yell and came in full speed

upon our lines, shooting and yelling as they came. Our lines held their position without a break. The notorious bushwhacker,

Anderson, and one of his men, supposed to be Captain Rains, son of General Rains, charged through our lines. Anderson was

killed and fell some fifty steps in our rear, receiving two balls in the side of the head. Rains made his escape and their

forces retreated in full speed, being completely routed."

Legacy

"Bloody Bill" Anderson is often remembered in the same sentence with the

likes of Frank and Jesse James, the Younger brothers, and his fellow Partisan, William Clarke Quantrill.

After the war, information about Anderson

initially spread through memoirs of Civil War combatants and works by amateur historians. He was later discussed in

biographies of Quantrill, which typically cast him as an inveterate murderer. Three biographies of Anderson were written after

1975. Asa Earl Carter's novel The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales features Anderson as a main character. In 1976, the book was adapted

into a film, The Outlaw Josey Wales, which portrays a man who joins Anderson's gang after his wife is killed by Union-backed

raiders. Anderson also appears as a character in several films about Jesse James.

| Bloody Bill Anderson Killed |

|

| Bloody Bill Anderson Dead (hours after his death) |

| Bloody Bill Anderson Grave Marker |

|

| Bloody Bill Anderson Gravesite |

Historians have been mixed in their appraisal of Anderson. Wood describes

him as the "bloodiest man in America's deadliest war" and characterizes him as the clearest example of the war's "dehumanizing

influence". Castel and Goodrich view Anderson as one of the war's most savage and bitter combatants, but they also argue that

the war made savages of many others. According to journalist T. J. Stiles, Anderson was not necessarily a "sadistic fiend",

but illustrated how young men became part of a "culture of atrocity" during the war. He maintains that Anderson's acts were

seen as particularly shocking in part because his cruelty was directed towards white Americans of equivalent social standing,

rather than targets deemed acceptable by American society, such as Native Americans or foreigners.

In a study of 19th-century warfare, historian James Reid posits that Anderson

suffered from delusional paranoia, which exacerbated his aggressive, sadistic personality. He sees Anderson as obsessed with,

and greatly enjoying, the ability to inflict fear and suffering in his victims, and suggests he suffered from the most severe

type of sadistic personality disorder. Reid draws a parallel between the bashi-bazouks and Anderson's group, arguing that

they behaved similarly. "Bloody Bill", like many during the conflict, may have also suffered from Posttraumatic

stress disorder (PTSD), shell shock, or battle fatigue.

Regardless of viewpoint, "Bloody Bill" Anderson remains a well-known figure

in American history and his impact and legacy is as vivid as one's imagination.

*Missouri Partisan rangers were

Confederate Partisan rangers. Quantrill's Raiders, moreover, were also known as Partisan rangers, guerrillas,

and bushwhackers.

(Sources and related reading below.)

Related Reading:

Sources: National Park Service; National Archives; Library of Congress; Castel, Albert E.; Goodrich, Thomas

(1998). Bloody Bill Anderson: The Short, Savage Life of a Civil War Guerrilla. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1506-5; Mayo,

Mike (2008). American Murder: Criminals, Crimes and the Media. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1-57859-191-6; Nichols, Bruce (2004).

Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri: 1863. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1689-9; Petersen, Paul R. (2007). Quantrill in Texas:

The Forgotten Campaign. Cumberland House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58182-582-4; Reid, James J. (2000). Crisis of the Ottoman

Empire: Prelude to Collapse 1839–1878. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07687-6; Schultz, Duane (1997). Quantrill's

War: The Life & Times Of William Clarke Quantrill, 1837–1865. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-16972-5; Stiles,

T. J. (2003). Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War. Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-70558-8; Sutherland, Daniel E. (2009).

A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3277-6;

Wood, Larry (2003). The Civil War Story of Bloody Bill Anderson. Eakin Press. ISBN 978-1-57168-640-4.

|