|

Frederick Douglass Biography

A Biography of the Life of Frederick Douglass

by Sandra Thomas

Frederick Douglass

An Introduction

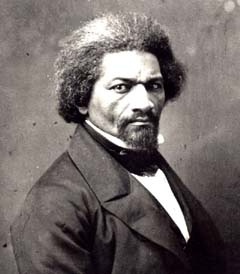

| Frederick Douglass (ca. 1866) |

|

| Frederick Douglass (ca. 1866) |

Frederick Douglass was one of the foremost leaders of the abolitionist

movement, which fought to end slavery within the United States in the decades prior to the Civil War.

A brilliant speaker, Douglass was asked by the American Anti-Slavery Society to engage in a tour of lectures,

and so became recognized as one of America's first great black speakers. He won world fame when his autobiography was publicized

in 1845. Two years later he began publishing an antislavery paper called the North Star.

Douglass served as an adviser to President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil

War and fought for the adoption of constitutional amendments that guaranteed voting rights and other civil liberties for blacks.

Douglass provided a powerful voice for human rights during this period of American history and is still revered today for

his contributions against racial injustice.

Frederick Douglass

Chapter One: The Slave Years

Frederick Baily was

born a slave in February 1818 on Holmes Hill Farm, near the town of Easton on Maryland's Eastern Shore.

The farm was part of an estate owned by Aaron Anthony, who also managed the plantations of Edward Lloyd V, one of the wealthiest

men in Maryland. The main Lloyd Plantation was near the

eastern side of Chesapeake Bay, 12 miles from Holmes Hill Farm, in a home Anthony had built near the Lloyd mansion, was where

Frederick's first master lived.

Frederick's mother, Harriet Baily, worked the cornfields surrounding Holmes Hill. He knew

little of his father except that the man was white. As a child, he had heard rumors that the master, Aaron Anthony, had sired

him. Because Harriet Baily was required to work long hours in the fields, Frederick

had been sent to live with his grandmother, Betsey Baily. Betsy Baily lived in a cabin a short distance from Holmes Hill Farm.

Her job was to look after Harriet's children until they were old enough to work. Frederick's

mother visited him when she could, but he had only a hazy memory of her. He spent his childhood playing in the woods near

his grandmother's cabin. He did not think of himself as a slave during these years. Only gradually did Frederick learn about a person his grandmother would refer to as Old Master and when she

spoke of Old Master it was with certain fear.

At age 6, Frederick's grandmother had told him that they were taking a long journey.

They set out westward, with Frederick clinging to his grandmother's

skirt with fear and uncertainty. They had approached a large elegant home, the Lloyd Plantation, where several children were

playing on the grounds. Betsy Baily had pointed out 3 children which were his brother Perry, and his sisters Sara and Eliza.

His grandmother had told him to join his siblings and he did so reluctantly. After a while one of the children yelled out

to Frederick that his grandmother was gone. Frederick fell to the ground and wept, he was about to learn the harsh realities of the slave

system.

The slave children

of Aaron Anthony's were fed cornmeal mush that was placed in a trough, to which they were called. Frederick later wrote "like so many pigs." The children made homemade spoons from oyster

shells to eat with and competed with each other for every last bite of food. The only clothing that they were provided with

was one linen shirt which hung to their knees. The children were provided no beds or warm blankets. On cold winter nights

they would huddle together in the kitchen of the Anthony house to keep each other warm.

One night Frederick was awakened by a woman's screams. He peered through a crack

in the wall of the kitchen only to see Aaron Anthony lashing the bare back of a woman, who was his aunt, Hester Baily. Frederick was terrified, but forced himself to watch the entire ordeal.

This would not be the first whipping he would see; occasionally he himself would be the victim. He would learn that Aaron

Anthony would brutally beat his slaves if they did not obey orders quickly enough.

Frederick's mother was rarely able to visit her children due to the distance between Holmes

Hill Farm and the Lloyd plantation. Frederick last saw his

mother when he was seven years old. He remembered his mother giving a severe scolding to the household cook who disliked Frederick and gave him very little food. A few months after this visit,

Harriet Baily died, but Frederick did not learn of this until

much later.

Because Frederick had a natural charm that many people found engaging, he was

chosen to be the companion of Daniel Lloyd, the youngest son of the plantation's owner. Frederick's

chief friend and protector was Lucretia Auld, Aaron Anthony's daughter, who was recently married to a ship's captain named

Thomas Auld. One day in 1826 Lucretia told Frederick that he was being sent to live with her

brother-in-law, Hugh Auld, who managed a ship building firm in Baltimore,

Maryland. She told him that if he scrubbed himself clean, she would give him

a pair of pants to wear to Baltimore. Frederick was elated at this chance to escape the life of a field hand. He cleaned himself

up and received his first pair of pants. Within three days he was on his way to Baltimore.

Upon Frederick's arrival at the Auld Home, his only duties were to run errands and care for the

Auld's infant son, Tommy. Frederick enjoyed the work and grew

to love the child. Sophia Auld was a religious woman and frequently read aloud from the Bible. Frederick asked his mistress to teach him to read and she readily consented. He soon learned

the alphabet and a few simple words. Sophia Auld was very excited about Frederick’s

progress and told her husband what she had done. Hugh Auld became furious at this because it was unlawful to teach a slave

to read. Hugh Auld believed that if a slave knew how to read and write that it would make him unfit for a slave. A slave that

could read and write would no longer obey his master without question or thought, or even worse could forge papers that said

he was free and thus escape to a northern state where slavery was outlawed. Hugh Auld then instructed Sophia to stop the lessons

at once!

Frederick learned from Hugh Auld's outburst that if learning how to read and write was his

pathway to freedom, then gaining this knowledge was to become his goal. Frederick

gained command of the alphabet on his own and made friends with poor white children he met on errands and used them as teachers.

He paid for his reading lessons with pieces of bread. At home Frederick

read parts of books and newspapers when he could, but he had to constantly be on guard against his mistress. Sophia Auld screamed

whenever she caught Frederick reading. Sophia Auld's attitude

toward Frederick had changed, she no longer regarded him as

any other child, but as a piece of property. However, Frederick

gradually learned to read and write. With a little money he had earned doing errands, he bought a copy of The Columbian

Orator, a collection of speeches and essays dealing with liberty, democracy, and courage.

Frederick was greatly affected by the speeches on freedom in The Columbian Orator,

and so began reading local newspapers and began to learn about abolitionists. Not quite 13 years old but enlightened with

new ideas that both tormented and inspired him. Frederick

began to detest slavery. His dreams of emancipation were encouraged by the example of other blacks in Baltimore, most of who were free. But new laws passed by southern state legislators made

it increasingly difficult for owners to free their slaves.

During this time,

Aaron Anthony died, and his property went to his two sons and his daughter, Lucretia Auld. Frederick remained a part of the Anthony estate and was sent back to the Lloyd plantation

to be a part of the division of property. Frederick was chosen by Thomas and Lucretia Auld

and was sent back to Hugh and Sophia Auld in Baltimore. Seeing

his family being divided up increased his hatred of slavery, however, he was hurt the most that his grandmother, considered

too old for any work, was evicted from her cabin and sent into the woods to die. Within a year of Frederick's

return to Baltimore, Lucretia Auld died. The two Auld brothers

then got into a dispute, and Thomas wrote to Hugh and demanded the return of his late wife's property, which included Frederick.

Frederick

was sorry to leave Baltimore because he had recently become

a teacher to a group of other young blacks. In addition, a black preacher named Charles Lawson had taken Frederick under his wing and adopted him as his spiritual son. In March of 1833, the 15 year

old Frederick was sent to live at Thomas Auld's new farm near the town of Saint Michaels, a few miles from the Lloyd plantation.

Frederick was again put to work as a field hand and was extremely unhappy about his situation.

Thomas Auld starved his slaves, and they had to steal food from neighboring farms to survive. Frederick received many beatings and saw worse ones given to others. He then organized a

Sunday religious service for the slaves which met in near by Saint Michaels. The services were soon stopped by a mob led by

Thomas Auld. Thomas Auld had found Frederick especially difficult

to control so he decided to have someone tame his unruly slave.

In January 1834, Frederick was sent to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had gained

a reputation around Saint Michaels for being and expert "slave breaker". Frederick

was not too displeased with this arrangement because Covey fed his slaves better than Auld did. The slaves on Covey's farm

worked from dawn until after nightfall, plowing, hoeing, and picking corn. Although the men were given plenty of food, they

had very little time allotted to eat before they were sent back to work. Covey hid in bushes and spied on the slaves as they

worked, if he caught one of them resting he would beat him with thick branches.

After being on the

farm for one week, Frederick was given a serious beating for

letting an oxen team run wild. During the months to follow, he was continually whipped until he began to feel that he was

"broken". On one hot August afternoon his strength failed him and he collapsed in the field. Covey kicked and beat Frederick to no avail and finally walked away in disgust. Frederick mustered the strength to get up and walk to the Auld farm,

where he pleaded with his master to let him stay. Auld had little sympathy for him and sent him back to Covey. Beaten down

as Frederick was, he found the strength to rebel when Covey

began tying him to a post in preparation for a whipping. "At that moment - from whence came the spirit I don't know - I resolved

to fight," Frederick wrote. "I seized Covey hard by the throat,

and as I did so, I rose." Covey and Frederick fought for almost two hours until Covey finally gave up telling Frederick that

his beating would have been less severe had he not resisted. "The truth was," said Frederick,

"that he had not whipped me at all." Frederick had discovered

an important truth: "Men are whipped oftenist who are whipped easiest." He was lucky, because legally a slave could be killed

for resisting his master. But Covey had a reputation to protect and did not want it known that he could not control a 16 year

old boy.

After working for

Covey for a year, Frederick was sent to work for a farmer

named William Freeland, who was a relatively kind master. But by now, Frederick

did not care about having a kind master. All Frederick wanted

was his freedom. He started an illegal school for blacks in the area that secretly met at night and on Sundays, and with five

other slaves he began to plan his escape to the North. A year had passed since Frederick

began working for William Freeland and his plan of escape had been completed. His group planned to steal a boat, row to the

northern tip of Chesapeake Bay, and then flee on foot to the free state of Pennsylvania. The escape was supposed to take place just before the Easter holiday in 1836,

but one of Frederick's associates had exposed the plot and

a group of armed white men captured the slaves and put them in jail.

Frederick was in jail for about a week. While imprisoned, he was inspected by slave traders,

and he fully expected that he would be sold to "a life of living death" in the Deep South.

To his surprise, Thomas Auld came and released him. Then Frederick's master sent him back to

Hugh Auld in Baltimore. The two brothers had finally settled

their dispute. Frederick was now 18 years old, 6 feet tall

and very strong from his work in the fields. Hugh Auld decided that Frederick

should work as a caulker (a man who forced sealing matter into the seams in a boat's hull to make it water tight) to earn

his keep. He was hired out to a local shipbuilder so that he could learn the trade. While apprenticing at the shipyard, Frederick was harassed by white workers who did not want blacks, slaves

or free, competing with them for jobs. One afternoon, a group of white apprentices beat up Frederick and nearly took out one of his eyes. Hugh Auld was angry when he saw what had happened

and attempted to press charges against the assailants. However, none of the shipyard's white employees would step forward

to testify about the beating. Free blacks had little hope of obtaining justice through the southern court system, which refused

to accept a black person's testimony against a white person. Therefore, the case had to be dropped.

After Frederick recovered from his injuries, he began apprenticing at the shipyard where Hugh Auld

worked. Within a year, he was an experienced caulker and was being paid the highest wages possible for a tradesman at his

level. He was allowed to seek his own employment and collect his own pay, and at the end of each week he gave all his earnings

to Hugh Auld. Sometimes he was allowed to keep a little money for himself. But as time passed, he became resentful of having

to give up his hard earned pay.

In Frederick's spare

time he met with a group of educated free blacks and indulged in the luxury of being a student again. Some of the free blacks

formed an educational association called the East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society, which Frederick had been admitted to. This is where Frederick

learned his debating skills. At one of the society's meetings, Frederick

met a free black woman named Anna Murray. Anna was a few years older than Frederick and was

a servant for a wealthy Baltimore family. Although Anna was

a plain, uneducated woman, Frederick admired her qualities

of thriftiness, industriousness and religiousness. Anna and Frederick were soon in love and in 1838 they were engaged.

Love and courtship

increased Frederick's discontent with his status. After Frederick's escape attempt, Thomas Auld had promised him that if he

worked hard he would be freed when he turned 25. But Frederick

did not trust his master, and he resolved to escape. However, escaping would be very difficult due to professional slave catchers

patrolling the boarders between slave states and free states,

and free blacks traveling by train or steamboat had to carry official papers listing their name, age, height, skin color,

and other distinguishing features. In order to escape, Frederick

needed money to pay for traveling expenses. Frederick arranged with Hugh Auld to hire out his

time, that is, Frederick would take care of his own room and

board and pay his master a set amount each week, keeping any extra money for himself. This also gave him the opportunity to

see what it was like living on his own.

This arrangement had

been working out quite well until Frederick returned home late one night and failed to pay Hugh Auld on time. Auld was furious

and revoked his hiring-out privilege. Frederick was so enraged

over this that he refused to work for a week. He finally gave in to Auld's threats, but he also made a resolution that in

three weeks, on September 3, 1838, he would be on a northbound train. Escaping was a difficult decision for Frederick. He would be leaving his friends and his fairly comfortable life in Baltimore forever. he did not know when and if he would see Anna Murray again. Furthermore,

if he was caught during his escape, he was sure that he would be either killed or sold to slave traders. Taking all of this

into consideration, Frederick was resolved to escape to freedom.

With money that he

borrowed from Anna, Frederick bought a ticket to Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania. He also had a friend's "sailor's protection," a document that certified

that the person named on it was a free seaman. Dressed in a sailor's red shirt and black cravat, Frederick boarded the train. Frederick reached northern Maryland before the conductor made it to the "Negro car" to collect

tickets and examine papers. Frederick became very tense when

the conductor approached him to look at his papers because he did not fit the description on them. But with only a quick glance,

the conductor walked on, and the relieved Frederick sank back

in his seat. On a couple of occasions, he thought that he had been recognized by other passengers from Baltimore, but if so

they did not turn him in to the authorities.

Upon

arriving in Wilmington, Delaware, Frederick

then boarded a steamboat to Philadelphia. Even after stepping

on Pennsylvania's free soil, he knew he was not yet safe

from slave catchers. He immediately asked directions to New York City,

and that night he took another train north. On September 4, 1838, Frederick arrived in New York City. Frederick

could not find the words to express his feelings of leaving behind his life in slavery. He later wrote, "A new world had opened

upon me." "Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted, but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill

of pen or pencil."

Frederick Douglass

Chapter Two: From Slave To Abolitionist and Editor

Alone in New York, Frederick soon realized that although he was free, he was not free of cares. Through word

of mouth on the street, Frederick learned that southern slave

catchers were roaming the city looking for fugitives in boarding houses that accepted blacks. He learned that no one, black

or white, could be trusted. After finding out this news, Frederick

wandered around the city for days, afraid to look for employment or a place to live. Finally, he told an honest-looking black

sailor about his predicament. The man took him to David Ruggles, an officer in the New York Vigilance Committee. Ruggles and

his associates were the City's link in the Underground Railroad, a network of people who harbored runaway slaves and helped

transport them to safe areas in the United States and Canada.

Secure for the moment

in Ruggle's home, Frederick sent for his fiancee, Anna Murray.

The two were married on September 15, 1838. Ruggles told Frederick that in the port of New Bedford, Massachusetts,

he would be safe from slave catchers and he could find work as a caulker. Upon arriving in New Bedford, Anna and Frederick stayed in the home of the well-to-do black family of Nathan

Johnson. To go along with his new life, Frederick decided

to change his name so as to make it more difficult for slave catchers to trace him. Nathan Johnson was at the time reading

The Lady of the Lake, a novel by Scottish author Sir Walter Scott, and he suggested that Frederick name himself after

a character in the book. Frederick Baily thus became Frederick Douglass.

Once settled, Douglass

was amazed to find that his neighbors in the North were wealthier than most slave owners in Maryland. He had expected that northerners would be as poor as the people in the South who

could not afford slaves. Many free blacks lived better than Thomas Auld or Edward Covey. On the New Bedford wharves, he saw how industry made extensive use of labor saving mechanical devices.

In loading a ship, 5 men and an ox did what it took 20 men to do in a southern port. To Douglass's eye, men who neither held

a whip nor submitted to it worked more quietly and efficiently than those who did.

Still, New Bedford was not a paradise. Although black and white children attended the same schools,

some public lecture halls were closed to blacks. Churches welcomed black worshipers but forced them to sit in separate sections.

Worst of all, white shipyard employees would not allow skilled black tradesmen, such as Douglass, to work beside them. Unable

to find work as a caulker, Douglass had to work as a common laborer. He sawed wood, shoveled coal, dug cellars, and loaded

and unloaded ships. Anna Douglass worked too as a household servant and laundress. In June 1839, Anna gave birth to their

first child, a daughter which they named Rosetta. A son, Lewis was born the following year.

After living in New

Bedford for only a few months, a young man approached Douglass and asked him if he wanted to subscribe to the Liberator,

a newspaper edited by the outspoken leader of the American Anti-Slavery Society, William Lloyd Garrison. Douglass immediately

became caught up in the Liberator's attacks on southern slaveholders. "The paper became my meat and drink," wrote Douglass.

"My soul was set all on fire."

Inevitably, Douglass

became involved in the abolitionist movement, regularly attending lectures in New

Bedford. The American Anti-Slavery Society, of which he was a member, had been formed in 1833. Like

Garrison, most of the leaders in the society were white, and black abolitionists sometimes had a difficult time making their

voices heard within the movement. Nonetheless, the black leaders kept up a constant battle to reduce racial prejudice in the

North. Douglass also became very involved with the local black community, and he served as a preacher at the black Zion Methodist Church. One of the many issues he became involved in was the battle against attempts

by white southerners to force blacks to move to Africa. Some free blacks had moved to Liberia, a settlement area established for them in West Africa

in 1822. Douglass, along with others in the abolitionist movement were opposed to African colonization schemes, believing

that the United States was the true home

of black Americans. In March 1839 some of Douglass's anticolonization statements were published in the Liberator.

In August 1841, at

an abolitionist meeting in New Bedford, the 23 year old Douglass

saw his hero, William Lloyd Garrison, for the first time. A few days later, Douglass spoke before the crowd attending the

annual meeting of the Massachusetts branch of the American

Anti-Slavery Society. Garrison immediately recognized Douglass's potential as a speaker, and hired him to be an agent for

the society. As a traveling lecturer accompanying other abolitionist agents on tours of the northern states, his job was to

talk about his life and to sell subscriptions to the Liberator and another newspaper, the Anti-Slavery Standard.

For most of the next 10 years, Douglass was associated with the Garrisonian school of the antislavery movement. Garrison was

a pacifist who believed that only through moral persuasion could slavery end, he attempted through his writings to educate

slaveholders about the evils of the system they supported. He was opposed to slave uprisings and other violent resistance,

but he was firm in his belief that slavery must be totally abolished. In the first issue of the Liberator in 1831,

he had written:

"On this subject

I do not wish to think, or speak, or write with moderation .....Tell a man whose house is on fire to give a moderate alarm;

tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of a ravisher.....but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like

the present.....I will not retreat a single inch----AND I WILL BE HEARD."

Ever controversial,

Garrison made many enemies throughout the country. He made sweeping attacks on organized religion because the churches refused

to take a stand against slavery. He also believed that the U.S. Constitution upheld slavery, for it stated that nonfree individuals

(slaves) should be counted as three-fifths of a person in the census figures used for determining a state's share of the national

taxes and its number of seats in the House of Representatives. Garrison said that abolitionists should refuse to vote or run

for political office because our government was so ill founded. He also called for the Union

to be dissolved, demanding that it be split between a free nation in the North and a slavehold confederacy in the South.

Garrison also supported

political equality for women and he fought to make it part of the abolitionist program. Some men were entirely against him

on this issue, while others thought that it distracted attention from the struggle against slavery. In 1840, when he insisted

that women be allowed to serve as delegates to abolitionist conventions, much of the membership of the American Anti-Slavery

Society split off and formed a separate organization. The new group, the Foreign and American Anti-Slavery Society, was not

opposed to working with political organizations, and many of its members supported the small, newly formed antislavery Liberty party. Although the often abrasive Garrison splintered the antislavery

movement, he was a powerful leader. His sincerity and passionate devotion to the abolitionist inspired many people, and his

views had a strong effect on Douglass. For three months in 1851, Douglass traveled with other abolitionists to lectures through

Massachusetts. Introduced as "a piece of property" or "a

graduate from that peculiar institution, with his diploma written on his back," he launched into stirring recollections of

his years in slavery. Many of his friends in New Bedford thought

that the publicity was dangerous for him, but he was careful to omit details that would identify him as the fugitive slave

Frederick Baily.

Douglass was an immediate

success on the lecture circuit. "As a speaker, he has few equals," proclaimed the Concord,

Massachusetts, Herald of Freedom, the newspaper praised his elegant use

of words, and his debating skills. "He has wit, arguments, sarcasm, pathos - all that first rate men show in their master

effort." His flashing eyes, large mass of hair, and tall figure added to his performance. Douglass's early speeches dealt

mainly with his own experiences. With dramatic effect, he told stories about the brutal beatings given by slaveowners to women,

children, and elderly people. He described how he had felt the head of a young girl and found it "nearly covered with festering

sores." He told about masters "breeding" their female slaves. But he also used humor, making his audiences laugh when he told

how he broke the slave breaker Edward Covey. He especially delighted in imitating clergymen who warned slaves that they would

be offending God if they disobeyed their masters. The stories that Douglass told were just what the people wanted to hear.

At the time, a flood of proslavery propaganda had been disbursed by southern writers to combat abolitionist literature. According

to these articles, most slaves were content with their easy life. Supposedly, slaves worked only until noon, dressed and ate

better than most poor whites, and enjoyed job security that would be envied by most northern factory workers. Many people

in the North were taken in by the slaveholders' fictions, and abolitionists were often harassed by hostile mobs.

Douglass's life story

refuted the proslavery accounts; even so, he declared, his years in bondage would be deemed blissful by many slaves laboring

in the Deep South. After a few months of speaking, Douglass began to add comments about the

racial situation in the North. He reminded the people in his audiences that even in Massachusetts

a black man could not always find work in his chosen profession. He described how he had been thrown out of railroad cars

that were exclusively for white passengers. Even here, he said, churches segregated their congregations and offered blacks

a second place in heaven. After Douglass's first trial period as a lecturer was over, he was asked to continue with his work,

and he eagerly agreed. During 1842, he traveled throughout Massachusetts and New York with William Lloyd Garrison and other prominent speakers. He also visited Rhode Island, helping to defeat a measure that would have given voting

rights to poor whites while denying them to blacks.

In 1843, Douglass

participated in the Hundred Conventions project, the American Anti-Slavery Society's six month tour of meeting halls throughout

the west. Although Douglass enjoyed his work immensely, his job was not an easy one. When traveling, the lecturers had to

live in poor accommodations. Douglass was often roughly handled when he refused to sit in the "Negro" sections of trains and

steamships, and worst of all some of the meetings that were held in western states were sometimes disrupted by proslavery

mobs. In Pendleton, Indiana,

Douglass's hand was broken when he and an associate were beaten up by a gang of thugs. Such incidents were common on the western

frontier, where abolitionists were often viewed as dangerous fanatics. Despite these incidents, Douglass was sure that he

had found his purpose in life.

His abilities as a

speaker grew as he continued to lecture in 1844. Many abolitionists thought he was growing in his ability too quickly and

that audiences were no longer as sympathetic to him, they thought it was best to keep a little of the plantation speech, it

was not a good idea for him to seem too learned. They advised him to stick to talking about his life as a slave and not about

the goals of the antislavery movement. To some degree, the fear proved to be correct. People gradually began to doubt that

Douglass was telling the truth about himself. Reporting on a lecture that he gave in 1844, the Liberator wrote that

many people in the audience refused to believe his stores: "How a man, only six years out of bondage, and who had never gone

to school could speak with such eloquence - with such precision of language and power of thought - they were utterly at a

loss to devise."

With his reputation

at stake, Douglass decided to publish the story of his life. During the winter of 1844-45, he set down on paper all the facts

- the actual names of the people and places connected with his years in slavery. When Douglass showed the finished manuscript

to abolitionist leader Wendell Phillips, his friend suggested that he dispose of it before he was found out and shipped back

to Maryland. Douglass was adamant about having his story printed. He did not care if Thomas Auld and every southern slave

catcher learned who he was, the rest of world would hear his story too.

In May 1845, 5,000

copies of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave was published. William Lloyd Garrison

and Wendell Phillips wrote introductions to the book. Almost immediately, Douglass's autobiography became a best seller. The

success brought by Douglass's Narrative after its publication in 1845 was due in large part to its moral force. His book is

a story of the triumph of dignity, courage, and self-reliance over the evils of the brutal, degrading slave system. It is

a sermon on how slavery corrupts the human spirit and robs both master and slave of their freedom. The book enjoyed widespread

popularity in the North, and European editions also sold very well. However, Douglass's fame as an author threatened his freedom.

Federal laws gave Thomas Auld the right to seize his property, the fugitive slave Frederick Baily.

The fear of losing

his freedom prompted Douglass to pursue a dream he had long held; in the summer of 1845 he decided to go to England. There he would be free from slave catchers, and also

have the opportunity to speak to English audiences and try to gain support for the American antislavery movement. By 1838

all slaves within the British Empire had been given a gradual emancipation and were free.

The vigor of the English abolition movement was still very strong.

As the wife of a traveling

lecturer, Anna Douglass had probably grown used to her husband's long absences. By August 1845, the Douglasses had 4 children:

6 year old Rosetta, 5 year old Lewis, 3 year old Frederick and 10 month old Charles. Anna not only raised the children, but

also toiled in a shoe factory in Lynn, Massachusetts

where the Douglasses had moved in 1842. Douglass sailed to England on the

British steamship Cambria. He was forced to stay in the steerage (second class) area of the

ship, but he made many friends on board and was even asked to give a lecture on slavery by the captain. Some men were so angry

at his speech that they threatened to throw him overboard. The captain had to step in and threaten to put the men in irons

if they caused any more trouble. The rest of the voyage was peaceful.

For nearly two years,

Douglass traveled throughout the British Isles. Everywhere he went, prominent people welcomed

him to their homes. Everywhere he spoke, enthusiastic crowds came to hear the fugitive slave denounce the system which he

had grown up in. He was quite happy in his new surroundings. As he wrote to William Lloyd Garrison in January 1846, "Instead

of the bright blue sky of America, I am

covered with the soft gray fog of the Emerald Isle. I breathe and lo! The chattel becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for

one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as a slave, or offer me an insult." He was also astonished that he encountered

so little racial prejudice among the British.

The main topic of

Douglass’s lecturers was slavery, but he also discussed a number of other causes that had become important to him. Douglass

had hated the way slaveowners would encourage their workers to drink themselves into a stupor during Christmas holidays. He

saw alcohol as another means used to humiliate slaves. During his stay in Ireland,

he also met with Daniel O'Connell, the Irish Catholic leader who was fighting to end British rule in his country. Douglass

spoke out in favor of Irish independence. In the summer of 1846, Douglass was joined by William Lloyd Garrison, and they traveled

around England as a powerful team of antislavery

lecturers. In Scotland, the two became

involved in a campaign against the Free Church of Scotland. The church was partly supported by contributions from American

slaveholders of Scottish ancestry. Douglass and Garrison added their voices to the cries of local antislavery activists: "Send

the money back." The church kept the money, but the dispute gained publicity for Douglass's battle against American slavery.

The World Temperance

Convention that was held in London in August 1846 was the

scene of Douglass's most controversial speech. There he attacked the American temperance movement because it failed to criticize

slaveowners who used alcohol to pacify their workers. He also felt that the temperance activists were hostile to free blacks.

The Reverend Samuel Cox, a member of the American delegation, publicly accused him of trying to destroy the unity of the temperance

movement. Douglass responded that Cox was a bigot and, like many other clergymen, a secret supporter of slavery.

By the fall of 1846,

Douglass was ready to return home. Garrison and other friends convinced him to stay another six months, but Douglass rejected

suggestions that he settle in England.

His work lay in America where his people

labored in bondage. However, recapture remained a frightening possibility for Douglass if he returned to the United States. The problem was unexpectedly resolved when

two English friends raised enough money to buy his freedom. The required amount, $710.96, was sent to Hugh Auld, to whom Thomas

Auld had transferred the title to Douglass. On December 5, 1846, Hugh Auld signed the papers that declared the 28 year old

Douglass a free man.

Douglass appreciated

the gesture of his English friends, even though as an abolitionist he did not recognize Hugh Auld's right to own him. In the

spring of 1847, Douglass sailed from England aboard the Cambria.

He had left the United States as a respected

author and lecturer and was returning with a huge international reputation. Thousands of people heard his lectures and he

aroused much goodwill for the abolitionist cause in the British Isles. His tour had been

an unqualified success.

Douglass was met by

friends and family upon returning home. However, some abolitionists criticized him for letting his freedom be bought because

he was thereby acknowledging Hugh Auld's right to own him. Douglass's rebuttal was that his freedom was the gift of friends

and that he recognized Hugh Auld as his kidnapper, not his master. Now that the ransom had been paid, he could fight the battle

against slavery with a free mind.

During his travels

in England, Douglass had demonstrated

some independence from the Garrison abolitionist faction, addressing a meeting sponsored by a rival antislavery group. Upon

his return to America, he decided to found

and edit a new abolitionist newspaper with the help of funds raised by his English friends. Garrison was opposed to this because

he needed Douglass as a lecturer and thought there were already enough abolitionists papers at the time. Douglass dropped

the idea for a while. In August 1847, he joined Garrison on a lecture tour throughout the North, Garrison became seriously

ill and Douglass was forced to continue the tour without him.

After

finishing the tour in the fall of 1847, he again began drawing up plans for a new abolitionist paper. The goal of his paper

would be to proclaim the abolitionist cause and fight for black equality. Rather than publish his paper in New England,, where

the Liberator was based, Douglass decided to move farther west, to Rochester,

New York.

Frederick Douglass

Chapter Three: The Rochester Years

Douglass bought a

two story home in Rochester, New York for Anna and the children and on December

3, 1847, Douglass began his second career, when his four page weekly newspaper, the North Star, came off the presses.

On the masthead appeared the motto, "Right is of no sex - Truth is of no color - God is the Father of us all, and we are all

Brethren." Once the North Star began to circulate, Douglass's friends in the abolitionist movement rallied to join

in praising it. However, not everyone was pleased to see another antislavery paper - especially one edited by an ex-slave.

Some local citizens were unhappy that their town was the site of a black newspaper, and the New York Herald urged the

citizens of Rochester to dump Douglass's printing press into Lake Ontario. Gradually, Rochester came to take pride in the North Star and its bold editor.

The town had a reputation

for being pro-abolitionist. Rochester's women were active in antislavery societies, and through them Douglass kept in close

contact with the leaders in the fight for women's rights, among them Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Along with the good will of Rochester's abolitionist and female

political activists, Douglass received encouragement from the local printer's union. The North Star received a number

of glowing reviews, but unfortunately the praises did not translate into financial success. The cost of producing a weekly

newspaper was high and subscriptions grew slowly. For a number of years, Douglass was forced to depend on his own savings

and contributions from friends to keep the paper afloat. He was forced to return to the lecture circuit to raise money for

the paper. During the paper's first year, he was on the road for six months. In the spring of 1848, he had to mortgage his

home.

In the midst of these

troubles, a friend from England arrived

to help Douglass with his financial problems. Julia Griffiths had raised enough money to help launch the paper, and now she

was prepared to fight for its survival. Griffiths put the

North Star's finances in order, and Douglass was eventually able to regain possession of his home. By 1851, he would

be able to write to his friend, the abolitionist publisher and politician Gerrit Smith, "The North Star sustains itself,

and partly sustains my large family. It has reached a living point. Hitherto, the struggle of its life has been to live. Now

it more than lives." Despite the ups and downs, Douglass's newspaper continued publication as a weekly until 1860 and survived

for three more years as a monthly. After 1851, it would be titled Frederick Douglass' Paper. Douglass's newspaper symbolized

the potential for blacks to achieve whatever goals they set. The paper provided a forum for black writers and highlighted

the success achieved by prominent black figures in American society.

For Douglass, starting

the North Star marked the end of his dependence on Garrison and other white abolitionists. The paper allowed him to

discover the problems facing blacks around the country. Douglass had heated arguments with many of his fellow black activists,

but these debates showed that his people were beginning to involve themselves in the center of events affecting their position

in America. By the end of the 1840's,

Douglass was well on his way to becoming the most famous and respected black leader in the country. He was in great demand

as a speaker and writer, he had proved himself to be and independent thinker and courageous spokesman for black liberty and

equality.

During his years in

Rochester, Douglass continued to grow in status as the editor

of the nation's best known black newspaper, in which he was free to attack slavery with all the power of his intellect. Yet

the turmoil of the 1850's would severely test his faith in the ability of America

to rid itself of the institution that kept his people in bondage. Some of the turmoil made its way into Douglass's home. While

he roamed far beyond his original bounds, his wife, though hard-working, remained uneducated and politically unambitious.

Douglass hired a teacher for Anna in 1848, hoping to bridge the gap between them. But his effort failed and Anna remained

almost totally illiterate.

Douglass appreciated

his wife's domestic skills, but he also admired the educated, politically active women who served in the antislavery and women's

rights movements. He was grateful for all the help the women abolitionists had given blacks, and in 1848, he showed his support

for the feminist cause by attending the first women's rights convention. The movement drew much hostile press, and the 35

women and 32 men who went to the convention were described as "manhaters" and "hermaphrodites" (people with both male and

female sexual features). The women delegates hesitated to make the demand for voting rights (suffrage) a part of their movement's

platform, and the feminist leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton asked Douglass to speak on the matter. With an appeal for bold action,

Douglass convinced the women that political equality was an essential step in their liberation.

The cause of women's

rights continued to remain important to Douglass. Susan B. Anthony and Lucretia Mott among many other feminists would be his

lifelong friends. A scandal erupted in 1848 when Julia Griffiths began to serve as Douglass's office and business manager

and soon became his almost constant companion. She arranged his lectures, dealt with the paper's finances and accompanied

him to meetings. People in Rochester gradually adjusted to

the sight of the black leader and the white woman walking arm in arm down the street. Rumors began to fly because Griffiths lived in the same house with Douglass and his wife. Anna Douglas

was uneasy about the local talk, but did not speak much about the situation. The controversy was reported in the newspapers,

and Douglass was attacked by the Garrisonians for involving the abolitionist movement in a scandal. In 1852, Griffiths decided to spare Douglass further embarrassment by moving out of his home. She

remained his close associate until 1855, when she returned to England.

Tensions between Douglass

and William Lloyd Garrison began to mount because Douglass's views on how to fight slavery gradually began to change and differed

sharply from Garrison's. The first principle of Garrison that Douglass began to question was the idea that resisting slavery

through violent means was wrong. In 1847, Douglass met with the militant white abolitionist John Brown, who helped to convince

Douglass that pacifist means could not by themselves bring an end to slavery. Brown had told him that slaveholders "had forfeited

their right to live, and that slaves had the right to gain their liberty in any way they could." At abolitionist meetings

Douglass began telling his audiences that he would be pleased to hear that the slaves in the South had revolted and "were

spreading death and destruction." Ten years later, he had completely abandoned the idea that slavery could be ended peacefully.

Douglass began widening his circle of abolitionist friends and thus began to question Garrison's opposition to seeking antislavery

reforms through the political process.

In 1848, he urged

women to fight for the vote. Garrison's view of the Constitution as a proslavery document was not accepted by all abolitionists,

as Douglass began to talk with these dissenters, he began to see the matter in a different way. The Constitution, with its

emphasis on promoting the general welfare and securing the blessings of liberty for all, clearly seemed to be antislavery.

The North, Douglass realized, would never abolish slavery if that could only be done by dividing the Union

and dismantling the Constitution. He therefore decided that slavery would have to be ended through political reforms. Garrit

Smith, who was a leader in the antislavery Liberty party became

associated with Douglass and got him involved in politics. In 1848, he attended a convention of the Free Soil party, which

was trying to stop the spread of slavery into areas west of the Mississippi River.

The final split between

Douglass and Garrison took place in June, 1851 at the annual meeting of the American Antislavery Society. Douglass shocked

his old associates by publicly announcing that he intended to urge the readers of the North Star to engage in politics.

The Garrisonian press launched a vicious assault against him during the following months. The disputes between the antislavery

factions did not dominate Douglass's life. He was active in any cause that furthered the cause of his people. Douglass also

tried to establish a black vocational school, an institution that would train its students to become skilled tradesmen. Among

the people he visited in his efforts to raise funds for the school was Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of the immensely

popular antislavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin . Unfortunately, Douglass was unable to raise enough money to start the

school.

Douglass was a proud

and loving father although he was often away from home. A fifth child, Annie, was born in 1849. Rochester's public schools would not admit black students so Douglass enrolled his oldest

child, Rosetta, into a private school. However, even there Rosetta was segregated from white students, and Douglass finally

hired a woman to teach his children at home. Never one to let racial discrimination go unchallenged, Douglass campaigned to

end segregation in Rochester's school system, and in 1857

his efforts succeeded.

In 1850, Douglass

became strongly involved in the Underground Railroad, the system set up by antislavery groups to bring runaways to sanctuaries

in the North and in Canada. Douglass's

home in Rochester was near the Canadian border, and during

the 1850s it became an important station on the Underground Railroad. Eventually, he became the superintendent of the entire

system in his area. He often found runaways sitting on the steps of his newspaper office when he arrived for work. At times,

as many as 11 fugitives were hiding in his home. Over the years, he and Anna fed and sheltered hundreds of these men and women.

Only a few of the slaves who tried to escape from the South were successful. Douglass fiercely attacked the fugitive slave

laws and the many atrocities that were being committed against runaway slaves.

In a speech given

in Rochester on Independence Day in 1852, Douglass pointed

out how differently blacks and whites viewed the day's celebrations: What to the American slave is your Fourth of July?

I answer, a day that reveals to him more than all the other days of the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he

is the constant victim...To him your celebration is a sham...a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation

of savages. There is not a nation of the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States. The sufferings of the hunted fugitive slaves

reminded Douglass that freedom for his people would not come easily. In a speech he made at a Canandaigua, New York, convention

celebrating the 20th anniversary of the emancipation of slaves in the British West Indies, Douglass preached that blacks must

unite to gain their liberty and that they must be prepared for a hard struggle. Blacks, he said, would have to pay a heavy

price to win their freedom. "We must do this by labor, by suffering, by sacrifice, and if needs be, by our lives and the lives

of others."

During the mid-1850s,

John Brown was the leader of one of the Free Soil bands fighting the proslavery forces in Kansas. But Brown wanted to start a slave revolt in the South. In 1859, he decided to lead

an attack on the northern Virginia town of Harpers

Ferry, seize the weapons stored in the nearby federal armory, and hold the local citizens hostage while

he rounded up slaves in the area. Gathering a small force of white and black volunteers, Brown rented a farm near Harpers Ferry and made his preparations for attack. From the farm, Brown wrote to Douglass, asking him

to come to a meeting in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania,

in August. There Brown announced his plans and urged Douglass to join in the attack. Douglass refused. He had agreed with

Brown's earlier ideas, but he knew that an attack on federal property would enrage most Americans.

This was the last

time Douglass and Brown met. On October 16, 1589, Brown and his men seized Harpers Ferry.

The next night, federal troops led by Colonel Robert E. Lee marched into the town and stormed the armory where Brown's band

was stationed. Brown was captured, and two of his sons were killed in the fighting. In less than two months, Brown was tried

for treason, found guilty, and hanged. Douglass was lecturing in Philadelphia

when he received the news about Brown's raid, and he was warned that letters had been found that implicated him in the attack.

The headlines for the newspapers' accounts of the incident featured his name prominently. Knowing that he stood little chance

of a fair trial if he were captured and sent to Virginia, Douglass fled to Canada. While Douglass was in Canada, he wrote letters in his own defense, justifying both his flight and his

refusal to help Brown. One of the men captured during the raid said that Douglass had promised to appear at Harpers

Ferry with reinforcements. Douglass denied this accusation, saying that he would never approve of attacks on federal

property. But though he could not condone the raid, he praised Brown as a "noble old hero."

In

November 1859, Douglass sailed to England to begin a lecture tour, a trip

he had planned long before the incident at Harpers Ferry. The news of his near arrest only

increased his popularity with his audiences, and his lectures helped to stir up more sympathy for the antislavery cause. In

May 1860, just as he was about to continue his lecture tour in France,

word reached him that his youngest child, Annie, had died. Heartbroken over the loss of his daughter, Douglass decided to

go home. Glad to be back with his family again, Douglass knew that he was home - and home included not just Rochester

but all of America, including the states

in the South. It was a home filled with strife, but it was his, and he embraced it all: the land, the people, the Constitution,

the Union.

Frederick Douglass

Chapter Four: The Civil War Years - The Fight For Emancipation

The election year of 1860

produced many candidates. The Democrats had split into factions; those who were proslavery supported Vice President John Breckinridge,

while moderates in the North favored the Illinois senator Stephen Douglas. Abraham Lincoln was the candidate

of the Republicans, who were opposed to the spread of slavery into new territories. The candidate from the newly formed Constitutional

Union Party, Gerrit Smith, was running on a strong antislavery platform.

At first, Douglass campaigned

for Smith. However, a few months before the election, Douglass decided that Smith had no chance of winning and chose instead

to back Lincoln. The two Democratic candidates received far

more votes than anyone else did, but the division in the party gave the presidency to Lincoln.

South Carolina, unwilling to accept the results of the election, seceded from the Union in December 1860. Abolitionists became the targets of angry mobs in the North, which blamed them

for dividing the nation. Northern attempts to win back the South were to no avail. In February 1861, six more southern states

- Georgia, Florida, Mississippi,

Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas

seceded and established a separate government under the name of the Confederate States of America.

The country waited for Lincoln to respond to the crisis. The president's address in March was

disappointing to Douglass because Lincoln promised to uphold

the fugitive slave laws and not interfere with slavery in the states where it was already established. His first priority

was to restore the Union, not to end slavery. On April 12, 1861, Confederate troops bombarded

Fort Sumter, a federal installation in the

harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The fort surrendered a day later. Lincoln

then called for 75,000 troops to be formed and sent to the South to stop the rebellion. Virginia,

Tennessee, North Carolina, and Arkansas immediately joined the Confederacy. The four other slave states - Delaware,

Maryland, Missouri, and Kentucky,

remained in the Union. The two sides prepared for battle, the North with its 23 states and

population of 22 million against the South's 11 states and 9 million people, including 3 and a half million slaves.

The North was fighting to

preserve the Union; the South was fighting for the right to secede and establish a nation

that guaranteed a person's right to own slaves. For Frederick Douglass and the abolitionists, the war was a battle to end

slavery. Douglass's response to the surrender of Fort Sumter was one of thanksgiving. As the Civil War got under way, Douglass marked out

two goals for which he would fight: emancipation for all slaves in the Confederacy and the Union border states, and the right of blacks to enlist in the armies of the North. As the war

progressed, more and more people in the North would come to agree with these aims. While battles raged throughout the South,

Douglass traveled on the lecture circuit, calling for Lincoln

to grant slaves their freedom. On April 16, 1862, the president signed a bill outlawing slavery in Washington, D.C., but he was slow to approve congressional

measures confiscating slaves in captured areas of the South. Lincoln believed that if he passed

laws that emancipated the slaves, the Union's border states

might rebel and join the Confederacy.

Douglass continued to insist

in his speeches and newspaper editorials that the aim of the war must be to abolish slavery and that blacks must be allowed

to join in the battle for their freedom. Battlefield casualties were frighteningly high, and antidraft riots erupted in northern

cities. Gradually, as the costly war dragged on, with no final victory in sight for the North, Lincoln began to realize that stronger actions needed to be taken against the Confederacy.

In the summer of 1862, Lincoln read to his cabinet a draft

of an order that would emancipate slaves in the Confederate states. He decided to issue the proclamation as soon as the North

won a major battle. In September, Lincoln got his victory when northern troops pushed back

a Confederate army at the bloody battle of Antietam in Maryland.

On the night of December 31, 1862, the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that as of the next day all

slaves in areas not held by Union troops were free. Slavery was not abolished in the border

states or in already captured areas of the South. Nevertheless, Lincoln's

act freed millions of blacks, who fled from their masters and took "freedom's road" to areas controlled by Union forces.

In Boston on the night that

the proclamation was announced, Douglass wrote of the spirit of those who had gathered with him at the telegraph office to

witness slavery's death: "We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky...we were watching...by the dim light

of the stars for the dawn of a new day...we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries." The crowds

cheered. The end of slavery was in sight. Douglass next turned his attention to the struggle of blacks to be allowed to fight

for their freedom. In 1863, Congress authorized black enlistment in the Union army. The Massachusetts

54th Regiment was the first black unit to be formed; the governor of the state asked Douglass to help in the recruitment.

Douglass agreed and wrote an editorial that was published in the local newspapers. "Men of Color, to Arms," he urged

blacks to "end in a day the bondage of centuries" and to earn their equality and show their patriotism by fighting

in the Union cause. His sons Lewis and Charles were among the first to enlist.

Douglass's recruitment speeches

promised black soldiers equality in the Union army, unfortunately they were not treated equally. They were paid 1/2 of what

the white soldiers received and were given inferior weapons and inadequate training. Blacks were not allowed to become officers.

Worst of all, black soldiers who were captured by Confederate troops were often shot. Douglass stopped his recruitment efforts

when he learned of these conditions. Douglass published his complaints and then requested to meet with the president. His

request was granted in the summer of 1863 and Douglass expressed his concerns about the way black soldiers were being treated

by Union officers and Confederate captors. President Lincoln did give Douglass some encouragement that changes might be made

in the future. Although Douglass was not entirely satisfied with Lincoln's

response, he decided to begin recruiting again. Shortly after the meeting, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton offered Douglass

a commission on the staff of General Lorenzo Thomas. Douglass accepted the offer and returned to Rochester, where he published the last issue of his newspaper. He waited at home for notice

of his commission as an officer, but it never arrived. Apparently, Stanton

decided that Douglass would never be accepted by other officers. Douglass was extremely disappointed that the commission fell

through, but he continued his recruiting work. By now, Frederick, Jr., had joined his brothers in the Union lines. More than

200,000 blacks enlisted in the Union army and 38,000 were killed or wounded in Civil War battles. Comprising about 10 percent

of the North's troops, the black soldiers made their numbers felt on the battlefields and distinguished themselves in many

engagements. By mid 1864, with the help of the spirited black troops, the war was slowly turning in favor of the North.

In 1864, Douglass was becoming

concerned about the fate of black Americans once they were all free. Douglass not only wanted liberation of the slaves, he

wanted equality for his people as well. In the North, discrimination against black soldiers and civilians continued. In May

1864, with the presidential elections approaching, Douglass attended a convention of abolitionists and antislavery members

of the Republican Party, who were known as radical Republicans. The delegates nominated the former Free Soil party candidate

and Union general John C. Fremont for president. The Democrats selected the popular general George McClellan to run against

Lincoln on a Copperhead platform. Copperhead was the derogatory

name used to refer to anyone who favored making immediate peace with the South and leaving slaves in bondage. Worried that

McClellan might win the election, Douglass and other Fremont supporters decided to back Lincoln.

Douglass and Lincoln had

a second meeting in August 1864. The president had begun to doubt that the war could be won, and he was worried that he might

have to sign a peace with the Confederacy that would leave slavery intact. Lincoln

asked Douglass to draw up plans for leading slaves out of the South in the event that a Union victory seemed impossible. Douglass

left the interview convinced that the president was a friend of blacks. The president's policies were hated not only by the

South but by many people in the North who had grown tired of war. The evacuation plan that Douglass sent to Lincoln never had to be used. In the summer of 1864, General William T. Sherman and his Union

troops left a path of destruction as they marched through the heart of the South. In September, Sherman

entered Atlanta, the capital of Georgia,

burned the city to the ground and left a path of destruction as he headed on to Savannah.

The victories gave the North renewed heart and helped Lincoln

win easy reelection in November.

By the end of 1864, the

South was hungry and bankrupt. As the Confederate armies retreated before their better-supplied opponents, Douglass took the

occasion to visit Maryland and Union - controlled areas of Virginia. He lectured in his old home town of Baltimore.

On this trip, he was reunited with his sister Eliza, whom he had not seen in 30 years. He was very proud of his sister, who

through her own hard work had managed to buy the freedom of herself and her nine children. Back in the North, Douglass attended

Lincoln's second inaugural address. Standing among crowds

gathered in the nation's capital, Douglass felt himself to be "a man among men." As though to prick that bubble, government

officials refused to allow Douglass or any other black to attend the evening reception in the White House. But when Douglass

sent word of this refusal to the president, he was quickly ushered in to the ceremony. Lincoln

personally greeted him with the words, "Here comes my friend Douglass."

In

the beginning of April, the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, was captured. A few days later, the commander of the Confederate forces, General

Robert E. Lee, surrendered to the Union commander, Ulysses S. Grant, at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. On April 9, 1865, the Civil War was over. To the horror of the newly reunited

nation, President Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, while attending a play at Ford's Theater in Washington on April 14. He died the next day. With the rest of the country, Douglass mourned

the man he had grown to respect. No sadness could completely overshadow Douglass's joy at this time, however. A single, glorious

fact remained: the war to end slavery had been won.

Frederick Douglass

Chapter Five: Life After the 13th Amendment

With the ratification of

the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in December 1865, slavery was officially abolished in all areas of the United

States. The Reconstruction era was under way in the South, the period during which the 11

Confederate states would be gradually reintroduced to the Union. In the meantime, Northern

armies continued to occupy the South and to enforce the decrees of Congress. Frederick Douglass was then 47 years old, an

active man in the prime of his life. No longer enlisted in the war on slavery, he thought about buying a farm and settling

down to a quiet life. But black Americans still desperately needed an advocate, and Douglass soon rejected any notion of an

early retirement.

In many parts of the South,

the newly freed slaves labored under conditions similar to those existing before the war. The Union army could offer only

limited protection to the ex-slaves, and Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, clearly had no interest in ensuring the freedom of southern

blacks. The new president's appointments as governors of Southern states formed conservative, proslavery governments. The

new state legislatures passed laws designed to keep blacks in poverty and in positions of servitude. Under these so-called

black codes, ex-slaves who had no steady employment could be arrested and ordered to pay stiff fines. Prisoners who could

not pay the sum were hired out as virtual slaves. In some areas, black children could be forced to serve as apprentices in

local industries. Blacks were also prevented from buying land and were denied fair wages for their work.

At a meeting of the American

Anti-Slavery Society in May 1865, one month after the end of the Civil War, William Lloyd Garrison had called upon the organization

to disband, now that its goal was achieved. Douglass came out against Garrison's proposal, stating that "Slavery is not abolished

until the black man has the ballot." The society voted to continue the struggle for black rights, but many abolitionists left

the movement. Fortunately, abolitionists were not the only ones interested in giving blacks the right to vote. The Republican

Party was worried that the Democrats would regain their power in the South. If this happened, the Republicans would lose their

dominant position in Congress when the southern states were readmitted to the Union. Led

by two fierce antislavery senators, Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner, a group of radical Republicans joined with abolitionists

in a campaign for voting rights for black men, who, they believed, would naturally support the Republicans. During the later

part of 1865, Douglass traveled throughout the North, speaking out for black suffrage and warning the country that the former

slaveholders were regaining control of the South. In February 1866, he addressed his most important audience, President Andrew

Johnson. Along with his son Lewis and three other black leaders, Douglass met with Johnson to impress upon him the need for

changes in the southern state governments. The president did most of the talking, and he told the delegation that he intended

to support the interests of southern whites and to block voting rights for blacks. Douglass and Johnson parted, both saying

that they would take their cases to the American people.

Despite the president's

opposition, Douglass and the supporters continued to battle for black rights with some success. The public mood gradually

turned against Johnson and his attempts to install governments in the South that were controlled by Confederate loyalists.

The Republican-controlled Congress became increasingly resistant to Johnson's plans for a limited reconstruction of the southern

states. The radical Republicans wanted to see sweeping changes enforced that would end the former slaveholders' power in the

South. Thaddeus Stevens urged that the estates of the large slaveholders be broken up and the land distributed to ex-slaves,

or freedmen, as they were then known.

In the summer of 1866, Congress

passed two bills over the president's veto. One, the Freedmen's Bureau Bill, extended the powers of a government agency that

had been established in 1865 for the purpose of providing medical, educational, and financial assistance for the millions

of impoverished southern blacks. Congress also passed the Civil Rights Bill, which gave full citizenship to blacks, along

with all the rights enjoyed by other Americans. President Johnson's supporters, mainly Democrats and conservative Republicans,

organized in the summer of 1866 to stop the movement for further black rights. The radical Republicans also held a meeting

in Philadelphia to vote on a resolution calling for black suffrage, and Douglass attended the

convention as a delegate from New York. Unfortunately, he

encountered much prejudice from some Republican politicians, who were unwilling to associate with blacks on an equal level.

Nonetheless, Douglass went to the convention and spoke out for black suffrage. The vote on the resolution was a close one,

for some of the delegates were afraid that white voters would not support a party that allied itself too closely with blacks.

Speeches by Douglass and

the woman suffragist Anna E. Dickinson helped turn the tide in favor of black suffrage. For Douglass, the convention also

held a more personal note. While marching in a parade of delegates, he spotted Amanda Sears, whose mother, Lucretia Auld,

had given him his first pair of pants and arranged for him to leave the Lloyd plantation. Sears and her two children had traveled

to Philadelphia just to see the famed Frederick Douglass.

The movement for black suffrage grew rapidly after the Philadelphia

convention. With President Johnson's supporters greatly outnumbered, in June 1866, Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment,

which was designed to ensure that rights guaranteed earlier to blacks under the Civil Rights Bill were protected by the Constitution.

The amendment was finally ratified in July 1868 after all the states approved it. Although the new amendment declared that

no state could deny any person his full rights as an American citizen, it did not guarantee blacks the right to vote. In most

states, however, blacks were already voting.

During July 1867, Douglass

was asked by President Johnson to take charge of the Freedman's Bureau, a position that would have allowed him to oversee

all the government programs administering to the needs of southern blacks. Douglass was tempted by the offer, the first major

post to be offered to a black man, but he realized that by associating with the Johnson administration, he would be helping

the president appear to be the black man's friend. Instead, he refused to serve under a man whose policies he detested. By

1867, Douglass could see that Johnson's days in office were numbered. The president was unable to stop Congress's Reconstruction

acts, which divided the South into five military districts and laid out strict guidelines for the readmission of the Confederate

states into the Union. The new laws required the southern states to ratify the Fourteenth

Amendment and to guarantee blacks the right to vote. The radical Republicans were angered by Johnson's attempts to block the

Reconstruction measures, and they instituted impeachment proceedings against him, the first time a president underwent this

ordeal. The impeachment measure fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority in the House and Senate needed to remove Johnson

from office, but the president exercised little power during the last two years of his term.

During the 1868 presidential

contest, Douglass campaigned for the Republican candidate, Ulysses S. Grant, the former commander in chief of the Union army.

In a famous speech, "The Work Before Us," Douglass attacked the Democratic party for ignoring black citizens and warned about

the rise in the South of white supremacist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan. These secret societies attempted to intimidate

blacks with fire and the hangman's noose. They also attacked "Yankee carpetbaggers" (northerners who had flooded into the

South at the end of the Civil War) and "scalawags" (southern whites who cooperated with the federal Reconstruction authorities).

Douglass feared that the terrorist tactics of the Klan would succeed in frightening blacks into giving up the civil rights

they had gained in the South. "Rebellion has been subdued, slavery abolished, and peace proclaimed," he said, "and yet our

work is not done.....We are face to face with the same old enemy of liberty and progress.....The South today is a field of

blood."

Black voters came out strongly

for the Republicans in the 1868 elections, helping Grant win the presidency. With Grant in office, the Fifteenth Amendment

passed through Congress and was submitted to the states for ratification. This amendment guaranteed all citizens the right

to vote, regardless of their race. Douglass's push for state approval of the amendment caused a breach between him and the

woman suffragists, who were upset that the measure did not include voting rights for woman. Old friends such as Susan B. Anthony

and Elizabeth Cady Stanton accused Douglass of abandoning the cause of women's rights. At the annual meeting of the Equal

Rights Association in May 1869, Douglass tried to persuade the woman suffragists that voting rights for blacks must be won

immediately, while women could afford to wait. "When women because they are women are dragged from their homes and hung upon

lampposts, .....then they will have the urgency to obtain the ballot," said Douglass. One of the women in the crowd cried

out, "Is that not also true about black women?" "Yes, yes," Douglass replied, "but not because she is a woman but because

she is black." The women in the audience were not convinced by Douglass's argument, and some of them even spoke out against

black suffrage. Douglass's relationship with the woman suffragists eventually healed, but women would not receive the right

to vote until 1920.

The campaign for state ratification

of the Fifteenth Amendment was successful. On March 30, 1870, President Grant declared that the amendment had been adopted.

Later, at the last official meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society, Douglass spoke gratefully about the new rights blacks

had won. "I seem to be living in a new world," he said. While thanking all the men and women who had struggled for so long

to make this new world possible, he modestly omitted his own name. However, no one had fought harder for black rights than

Douglass. By 1870, he could look proudly upon some of the fruits of his labors. Between 1868 and 1870, the southern states

were readmitted to the Union, and large numbers of blacks were elected to the state legislatures.

Blacks also won seats in Congress, with Hiram Revels of Mississippi becoming the first black senator and Joseph Rainey of

South Carolina being the first black to enter the House

of Representatives. In 1870, Douglass was asked to serve as editor of a newspaper based in Washington, D.C., whose goal was to herald the progress

of blacks throughout the country. Early on, the paper, the New National Era, experienced financial difficulties, and

Douglass bought the enterprise. The paper folded in 1874, but for a few years it provided him with the means to publish his

opinions on the developing racial situation in the United States.

Another misfortune occurred

in 1872, when Douglass's Rochester home went up in flames.

None of his family was hurt, but many irreplaceable volumes of his newspapers were destroyed. Although friends urged him to

rebuild in Rochester, Douglass decided to move his family to the center of political activity

in Washington, D.C. During

1872, Douglass campaigned hard for the reelection of President Grant. He supported the president even though many of the Republican