|

Organization of the Federal

Navy

Union Navy Organization

and History

Organization of the US Navy

| Union Navy Organization |

|

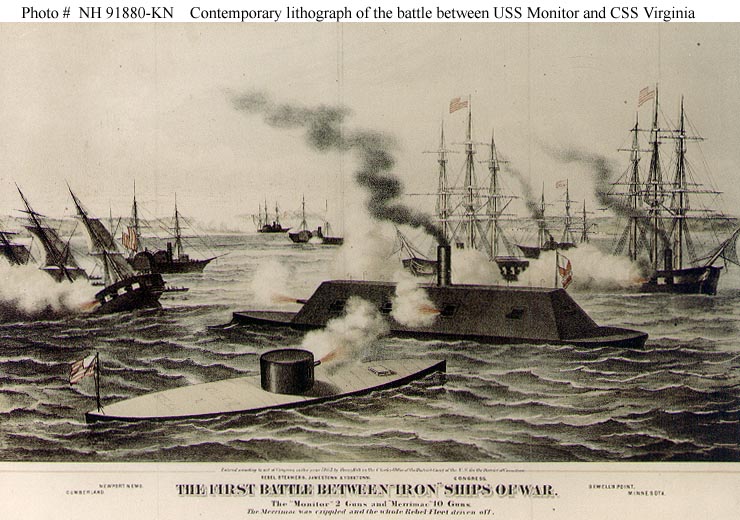

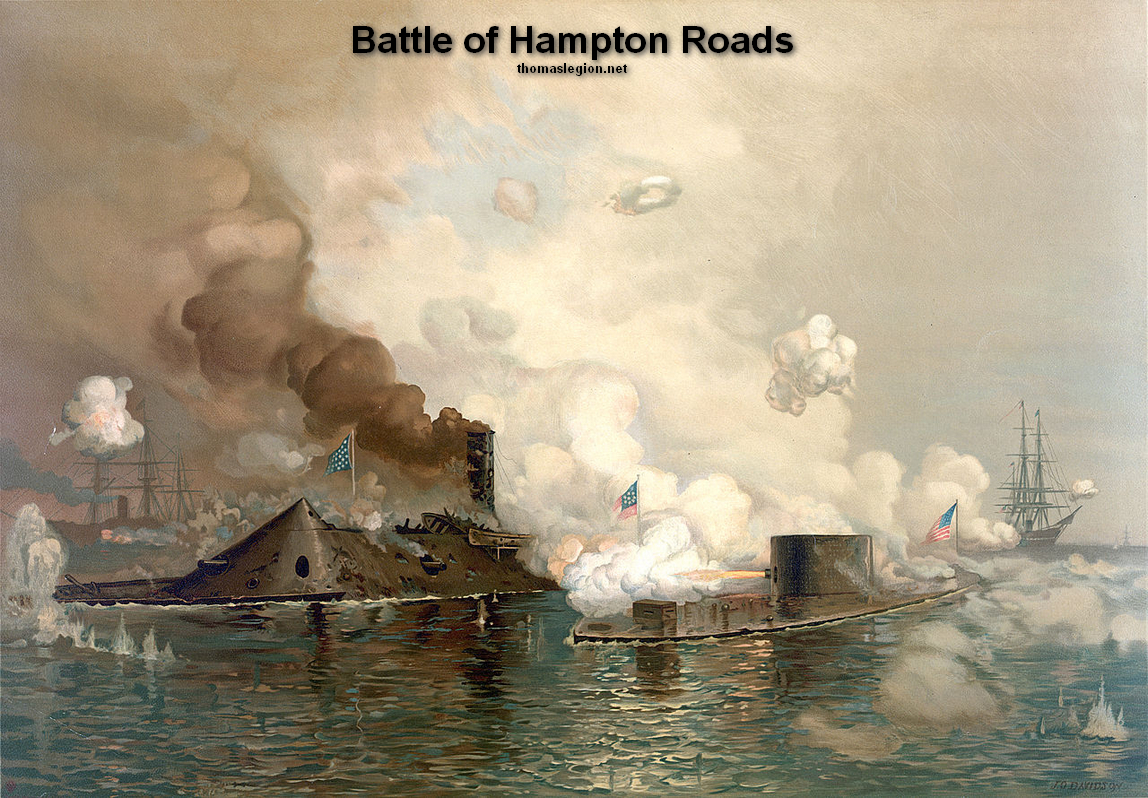

| Union and Confederate Navies in the Battle of Hampton Roads |

WHEN President Lincoln and his administration found themselves confronted with the most stupendous problem that any nation

had as yet to face, there was one element in their favor that counted more heavily than any other, an element whose value

has been overlooked by the early historians of the war. It was the possession not only of a navy but of shipyards and a vast

merchant marine from which to draw both vessels and men, and thus to increase the Northern fighting efficiency at sea.

Though both North and South were wholly unprepared for the gigantic

struggle, at the command of the Federal Government were inexhaustible resources. Manufactories and establishments of all kinds

were at hand, together with shipbuilding yards that had turned out a merchant marine which, previous to the outbreak of hostilities,

had gained the commerce-carrying supremacy of the world. These factors and advantages were of tremendous importance in contributing

to the final success of the Federal cause. Not only was the part of the trained sailor significant, but the mechanic and inventor

found a peculiar scope and wide field for development in the application of their genius and talents to the navy's needs.

In five years, the whole science of naval warfare was to be changed; the wooden fleets of Europe were to become antiquated and practically

useless, and the ironclad whose appearance had been adumbrated was now to become a reality for all sea fighting.

Ninety ships of war made up the United States navy at the opening of the year 1861, but of these only forty-two

were in any measure ready for active service; the remainder were laid up at various dockyards awaiting repairs of a more or

less extended nature. Of the forty-two ships that could be made ready for duty, the majority were steam-propelled vessels

of the latest improved types. The United States

had been one of the first world-powers to realize the value of steam as an auxiliary to sail. In the twenty years previous

to the opening of the Civil War, practically a new navy had been constructed, ranking in efficiency third only to those of

England and France.

There were many of the older vessels included in the active list, and some still in commission that bore historic names and

had seen service in the War of 1812. They had been the floating schools for heroes, and were once more called to serve their

turn.

The newer ships comprised a noble list. Within five years previous

to the outbreak of hostilities, the magnificent steam frigates Merrimac, Niagara, Colorado, Wabash, Minnesota, and Roanoke

had been built, and the fine steam sloops-of-war Hartford, Brooklyn, Lancaster, Richmond, Pensacola, Pawnee, Michigan, Narragansett,

Dacotah, Iroquois, Wyoming, and Seminole had been placed in commission. These ships were of the highest developed type of

construction and compared favorably at that time with any war vessels in the world.

Summing up the serviceable navy, we find that it consisted of two sailing

frigates, eleven sailing sloops, one screw frigate, five screw sloops of the first class, three side-wheel steamers, eight

screw sloops of the second class, and five screw sloops of the third class. Available, but laid up in various yards, were

other vessels, including eighteen propelled by sail alone, five screw frigates, one screw sloop, and three or four side-wheel

steamers. Yet, in spite of all this showing, at the opening of the year 1861 there was presented to the Nation a remarkable

condition of affairs--a condition that it is almost unbelievable that it should have existed. The country stood aghast at

its own unpreparedness. There were but two ships available to guard the entire Atlantic coast!

At Hampton Roads lay the steam sloop Brooklyn, and at New York lay the store-shider of the serviceable ships actually in commission were scattered

in all parts of the earth. The Niagara, a screw frigate and the first built by Steers, the

famous clipper-ship constructor, was the farthest away from the Atlantic ports. She was on special duty in Japanese waters,

and in the best of circumstances could not report where her services were most needed for several months.

The rest of the ships on foreign stations would require from a week

to a month to gain home waters. Of the forty-eight ships that were in dock or in the navy-yards, there was none that could

be prepared for service within a fortnight, and there were many that would require a month or more before they would be ready.

From the time of the secession of South Carolina, in December, 1860,

to the time of the declaration of war, valued officers of the navy whose homes were in the South had been constantly resigning

from the service. The Navy Department was seriously hampered through their loss. Shortly after the opening of the war, it

became necessary to curtail the course at the Naval Academy

at Annapolis, and the last-year class was ordered on active

duty to fill the places made vacant by the many resignations. At the opening of the war, the Federal navy had fourteen hundred

and fifty-seven officers and seventy-six hundred seamen. This number was constantly increased throughout the war, and at the

close there were no less than seventy-five hundred officers and fifty-one thousand five hundred seamen.

When the Lincoln

administration came into power in 1861, the Secretary of the Navy under the Buchanan administration, Isaac Toucey, of Hartford, Connecticut, was succeeded

by his fellow townsman, Gideon Wells, whose experience as chief of the bureau of provisions and clothing in the Navy Department

from 1846 to 1849 had familiarized him with the details of department work. Under Wells, as assistant secretary, was appointed

Gustavus V. Fox, a brilliant naval officer, whose eighteen years in the service had well fitted him for the work he was to

take up, and whose talents and foresight later provided valuable aid to the secretary. At the head of the bureau of yards

and docks was Joseph Smith, whose continuous service in the navy for nearly a half-century and whose occupancy of the position

at the head of the bureau from 1845 had qualified him also to meet the unlooked-for emergency of war.

Under the direction of the secretary, there were at this time a bureau

of ordnance and hydrography, a bureau of construction, equipment, and repair, a bureau of provisions and clothing, and a bureau

of medicine and surgery. It was soon found that these bureaus could not adequately dispose of all the business and details

to come before the department, and by act of Congress of July 5, 1862, there was added a bureau of navigation and a bureau

of steam engineering. The bureau of construction, equipment, and repair was subdivided into a bureau of equipment and recruiting

and a bureau of construction and repair.

In William Faxon, the chief

clerk of the Navy Department, Secretary Wells found the ablest of assistants, whose business ability and mastery of detail

were rewarded in the last months of the war by his being appointed assistant secretary while Mr. Fox was abroad.

With the organization of the new Navy Department, steps were taken

at once to gather the greater number of the ships of the Federal fleets where they could be used to the utmost advantage.

Work on the repairing and refitting of the ships then laid up in the various navy-yards was begun, and orders were given for

the construction of a number of new vessels. But in the very first months of the actual opening of the war, the Navy Department

dealt itself the severest blow that it received during the whole course of hostilities. Lying at the Gosport Navy-Yard at

Norfolk, Virginia, were some of the navy's strongest, most formidable, and most historic ships--the steam frigate Merrimac,

of forty guns, that was soon to make the world ring with her name; the sloop-of-war Germantown, of twenty-two guns; the Plymouth,

of the same number, and the brig Dolphin.

There were, besides, the old sailing vessels whose names were dear

to the country: to wit, the Pennsylvania, a line-of-battle ship; the United States, Columbus, Delaware,

Rariten, and Columbia. There was also on the stocks, and unfinished,

a ship of the line, the New York.

There is not time or space in this short preamble to enter into the

reasons for what happened, but through blunders and a feeling of panic, the fiat went forth that the navy-yard and all it

contained should be destroyed. On the night of April 20th, this order was carried into effect, and over two million of dollars'

worth of Federal property was destroyed, besides vast stores and ammunition. Thousands of cannon fell into the hands of the

new-born Secessia. It was a bitter chapter for the cooler heads to read. All along the coast of the Southern States, other

vessels which could not be removed from docks or naval stations were seized by the Confederate Government or destroyed by

orders from Washington.

| Battle of the Ironclads Monitor and Virginia |

|

| Battle of the Ironclads USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (aka Merrimack or Merrimac) |

As if suddenly recovered from the fever of apprehension that

had caused so much destruction, the Federal Government soon recognized its necessities, and the Navy Department awoke to the

knowledge of what would be required of it. Immediately, the floating force was increased by the purchase of great numbers

of vessels of all kinds. Of these, thirty-six were side-wheel steamers, forty-two were screw steamers, one an auxiliary steam

bark, and fifty-eight were sailing craft of various classes. These vessels mounted a total of five hundred and nineteen guns,

of which the steam craft carried three hundred and thirty-five. In addition to these, the navy-yards were put to work at the

building of new vessels, twenty-three being in process of construction at the close of the year in the Government shipyards,

and one at the New York Navy-Yard being built by a private contractor.

Every place where serviceable ships could be laid down was soon put

to use, and in private yards, at the close of 1861, twenty-eight sailing vessels were being constructed, fourteen screw sloops,

twenty-three screw gunboats, and twelve side-wheelers. Besides these, there were early on the ways three experimental iron-clad

vessels, the value and practicability of which in battle was at this time a mooted question.

One of these three soon-to-be-launched ironclads was an innovation

in naval construction; one hundred and seventy-two feet in length, she was over forty-one feet in beam, and presented a free-board

of only eighteen inches above the water. Almost amidships she carried a revolving turret, twenty-one feet in diameter and

nine feet high. The inventor of this curious craft, which was building at the Continental Iron Works in New York,

had absolute faith in her future, a faith that was shared by very few naval men of the day. On the 9th of March, 1862, this

"freak," this "monstrosity," this "waste of money" fought her first battle, and marked the closing of one era of naval history

and the opening of another. Ericsson and the Monitor are names linked in fame for all time to come.

The other two ironclads that were contracted for in 1861 were on the

lines of the battle-ship of the day. Heavily armored with iron and wood, they were adapted to the mounting of heavier guns

than were then generally in use. No wooden vessel could live for a moment in conflict with them, broadside to broadside.

From the very first, the Lincoln

administration had fully understood and comprehended the naval weakness of the South. But not only this, it knew well her

dependence on other countries for supplies and necessities, and how this dependence would increase. Almost the first aggressive

act was to declare a blockade of the Atlantic coast south of the Chesapeake, and this was quickly

followed by proclamations extending it from the Gulf to the Rio Grande.

Long before there were enough vessels to make the blockade effective, this far-reaching action was taken. But now, as the

navy grew, most of the purchased ships were made ready for use, and before the close of 1861, were sent southward to establish

and strengthen this blockade, and by the end of the year the ports of the Confederacy were fairly well guarded by Federal

vessels cruising at their harbors' mouths. The expedition to Hilton Head and the taking of Forts Walker and Beauregard had

given the navy a much coveted base on the Southern shore. Still, every month new vessels were added, and there was growing.

on the Mississippi a fleet destined for a warfare new in

naval annals. Seven ironclads were built and two remodeled under the supervision of Captain James B. Fads. There were also

three wooden gunboats, and later on, in the summer of 1862, at the suggestion of Flag-Officer Davis, the fleet of light-draft

vessels, known as "tin-clads," was organized.

For some time the gunboats and "tin-clads" operating in conjunction

with the Western armies had been under the supervision of the War Department, and separate from the navy entirely. But very

soon this was to be changed, and the entire Mississippi

forces and those engaged in the Western and Southern waters came under the jurisdiction of the Navy Department. Officers were

detached to command of these nondescript and "tin-clads" that rendered such gallant service; experienced gunners and bodies

of marines were sent out to lend discipline and cohesion to the land sailors who, up to this time, had been carrying on the

river warfare. The blockade called for more and more energy along the Atlantic coast; very early the "runners" began to try

the dangerous game of eluding the watching cordon.

Providing these vessels with officers and crews taxed the Navy Department

to a great extent. There were not enough experienced men then in the navy to officer more than a small portion of the ships

brought into service, and it was necessary to call for recruits. The merchant marine was drawn on for many valuable men, who

filled the stations to which they were assigned with credit to themselves and the navy. It may be said to the credit of both

the merchant marine and the "service," however, that the consequent jealousy of rank that at times was shown resulted in nothing

more serious than temporary dissatisfaction, and was seldom openly expressed. The men of both callings had been too well trained

to the discipline of the sea to question the orders of their superiors, and after the distribution of commissions usually

settled down to a faithful and efficient discharge of the duties to which they had been assigned.

From the outset of the war, it appeared more difficult to secure enlistments

for the navy than for the army, and with the constant addition of ships it finally became necessary to offer large bounties

to all the naval recruits in order to keep the quota up to the required numbers. During the war the United States navy built two hundred and eight vessels and purchased four hundred

and eighteen. Of these, nearly sixty were ironclads, mostly monitors.

With the introduction of the ironclad and the continual increase of

the thickness and efficiency of the armor as the war progressed, the guns of the navy also changed in weight and pattern.

The advent of the ironclad made necessary the introduction of heavier ordnance. The manufacturers of these guns throughout

the North were called upon to provide for the emergency. At the beginning of the war, the 32-pounder and the 8-inch were almost

the highest-power guns in use, though some of the steam vessels were provided with 11-inch Dahlgren guns. Before the war had

closed, the 11-inch Dahlgren, which had been regarded as a "monster" at the start, had been far overshadowed, and the caliber

had increased to 15-inch, then 18-inch, and finally by a 20-inch that came so late in the war as never to be used. Rifled

cannon were also substituted for the smooth-bore guns.

The navy with which the Federals ended the war belonged to a different

era from that which it started, the men to a different class. Very early in 1862, the number of artisans and laborers employed

in the Government navy-yards was increased from less than four thousand to nearly seventeen thousand, and these were constantly

employed in the construction and equipment of new ships, embracing all the improvements that could be effectively used, as"

soon as they were shown to be practical.. In addition to these seventeen thousand men, there were fully as many more engaged

by private contractors, building and equipping other vessels for the service.

One of the navy in the Civil

War, and before referred to, was the "tin-clad" fleet, especially constructed to guard the rivers and shallow waters of the

West and South. The principal requirement of these "tin-clads" was that they be of very light draft, to enable them to navigate

across the shoals in the Mississippi and other rivers on

which they did duty. The lighter class of these vessels drew less than two feet of water, and it was a common saying that

they could" go anywhere where the ground was a little damp." They were small side- or stern-wheel boats, and were armored

with iron plating less than an inch in thickness, from which they derived the name of "tin-clads." Though insufficient protection

to resist a heavy shell, this light plating was a good bullet-proof, and would withstand the fire of a light field-piece,

unless the shell chanced to find a vulnerable spot, such as an open port-hole.

These boats were armed with howitzers, and their work against field-batteries

or sharpshooters on shore was particularly effective. The heavier class of boats that were used in the river offensive and

defensive work was armed with more guns of larger caliber, and their armor-plating was somewhat heavier than that of the little

vessels designed to get close to the shores. The little boats, however, took their full share in the heavy fighting, and on

the Red River, with Admiral Porter standing at he pilot had fallen, the Cricket, one of the

smallest of these light-armored boats, fought one of the most valiant small naval contests of the war. Others of these boats

won distinction in their actions against shore forces and heavier vessels.

In spite of the number of ships built and equipped during the war,

and the other heavy expenses which the War Department incurred, the total cost of the navy during the war was little over

$314,000,000, or but nine and three-tenths per cent. of the total cost of the war.

The pay of the officers and men in the navy, unlike that of the volunteers

enlisted in the army, was regulated by the length of term of service and by the duty the officer was called upon to perform.

The captain's rank, which was the highest position held in the Federal navy at the opening of the war, was the only one in

which the length of service did not bring an increase of pay. The pay of a captain commanding a squadron, which was equivalent

to the rank of rear-admiral, later established, was $5000 a. year; the pay of the captain who ranked as senior flag-officer

was $4500 a year; captains on all other duties at sea received $4200 a year; on shore duty, $3600 a year, and on leave or

waiting orders, $3000 a year. Commanders on duty at sea received $2825 a year for the first five years after the date of commissions,

and $3150 a year during the second five years. On other duty, the commanders received $2662 for the first five years after

the date of commissions, and $2825 for the second five years. All other commanders received $2250 a year.

A lieutenant commanding at sea received $2550 a year. Other lieutenants

on duty at sea received $1500 a year until they had served seven years, when their first increase in pay brought the amount

up to $1700. Following this, until they had served thirteen years, they received an increase of two hundred dollars each two

years, or $2250 a year at the expiration of thirteen years. On leave or waiting orders the lieutenant's pay graded up similarly,

but in smaller amounts. at the end of thirteen years his pay was $1450. The surgeon of a fleet received $3800 a year, but

all other surgeons were paid on the sliding scale, with an increase in pay each five years until twenty years had elapsed,

when the final raise was given. For surgeons on duty at sea the range was from $2200 a year for the first five years to $3000

a rear after twenty years. On other duty, the range was from $2000 to $2800, and on leave or waiting orders from $1600 to

$2300. The pay of assistant surgeons ranged from $800 to $1500 a year, regulated by their proficiency and the duty they were

performing.

The paymaster's pay was increased each five years up to the twentieth,

when the final increase was given. It ranged from $1400 a year for the first five years on leave or waiting orders to $3100

a year after twenty years while on duty at sea. The pay of chief engineers on duty ranged from $1800 a year for the first

five years to $2600 a year after fifteen years' service. The pay of assistant engineers ranged from $600 a year for third

assistants on leave and waiting orders to $1250 for first assistants on duty.

The pay of the gunners was increased each three years until they had

served twelve years. For the first three years after date of warrant, while on duty at sea, the gunners received $1000 a year,

and after twelve years' service their pay was $1450. On other duty, the pay of the gunners ranged from $800 to $1200. Boatswains

and carpenters received the same pay as the gunners. Midshipmen received $550 when at sea, $500 when on other duty, and $450

when on leave of absence or waiting orders. Passed midshipmen, or midshipmen who had qualified to receive a commission without

further sea duty, received $1000 a year when on duty at sea, $800 when on other duty, and $650 when on leave or waiting orders.

Naval chaplains received the same pay as lieutenants. The pay-scale tapered down through the various grades of seamen, until

the "boys, all the youngsters engaged in the powder-monkeys," "water-boys," and various other duties, received ten dollars

a month and their rations.

Early in the war, the Navy Department was confronted by a serious problem

that manifested itself in the numbers of "contrabands," or runaway slaves that made their way into the navy-yards and aboard

the Federal ships, seeking protection. These contrabands could not be driven away, and there was no provision existing by

which they could be put to work and made useful either on board the ships or in the navy-yards. The situation was finally

brought to the attention of the Secretary of the Navy, and be was asked to find some remedy. Under date of the 25th of September,

1861, he issued an order 'that from that date the contrabands might be given employment on the Federal vessels or in the navy-yards

at any necessary work that they were competent to do. They were advanced to the ratings of seamen, firemen, and coal-heavers,

and received corresponding pay.

The principal yards where the construction work the Federal navy was

carried on were those at New York, Philadelphia, Portsmouth, and Boston.

Early in the war, the Naval Academy was removed to Newport, Rhode Island,

"for safe-keeping," but in 1865, when invasion was an impossibility and the dwindling forces of the South were mostly confined

to the armies of Johnston and Lee, south of the James, the academy once more returned to its old home. There were many young

men of the classes of 1861 and 1862 who found themselves shoulders high above the rank generally accredited to officers of

their years. For deeds of prowess and valor they had been advanced many numbers in the line of promotion. The classes of 1865

and 1866 were very large; and for a long time after the reduction of the naval establishment, promotion in the service became

exceedingly slow.

Source: Photographic History of

the Civil War, Volume 3

Recommended

Reading:

Lincoln's Navy: The Ships,

Men and Organization, 1861-65 (Hardcover). Review: Naval historian Donald L. Canney provides a good overview

of the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, describing life at sea, weapons, combat, tactics, leaders, and of course, the ships

themselves. He reveals the war as a critical turning point in naval technology, with ironclads (such as the Monitor) demonstrating

their superiority to wooden craft and seaborne guns (such as those developed by John Dahlgren) making important advances.

The real reason to own this oversize book, however, is for the images: more than 200 of them, including dozens of contemporary

photographs of the vessels that fought to preserve the Union. There are maps and portraits,

too; this fine collection of pictures brings vividness to its subject that can't be found elsewhere.

Recommended

Reading:

Civil War Ironclads: The U.S. Navy and

Industrial Mobilization (Johns Hopkins

Studies in the History of Technology). Description: "In this impressively researched and broadly conceived study, William

Roberts offers the first comprehensive study of one of the most ambitious programs in the history of naval shipbuilding, the

Union's ironclad program during the Civil War. Perhaps more importantly, Roberts also provides

an invaluable framework for understanding and analyzing military-industrial relations, an insightful commentary on the military

acquisition process, and a cautionary tale on the perils of the pursuit of perfection and personal recognition." - Robert

Angevine, Journal of Military History "Roberts's study, illuminating on many fronts, is a welcome addition to our understanding

of the Union's industrial mobilization during the Civil War and its inadvertent effects on the postwar U.S. Navy." - William

M. McBride, Technology and Culture"

Recommended

Reading: Lincoln and His Admirals (Hardcover).

Description: Abraham Lincoln began his presidency admitting that he knew "little about ships," but he quickly came to preside

over the largest national armada to that time, not eclipsed until World War I. Written by prize-winning historian Craig L.

Symonds, Lincoln and His Admirals unveils an aspect of Lincoln's presidency unexamined by historians until now, revealing

how he managed the men who ran the naval side of the Civil War, and how the activities of the Union Navy ultimately affected

the course of history. Continued below…

Beginning with

a gripping account of the attempt to re-supply Fort Sumter--a comedy of errors that shows

all too clearly the fledgling president's inexperience--Symonds traces Lincoln's

steady growth as a wartime commander-in-chief. Absent a Secretary of Defense, he would eventually become de facto commander

of joint operations along the coast and on the rivers. That involved dealing with the men who ran the Navy: the loyal but

often cranky Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, the quiet and reliable David G. Farragut, the flamboyant and unpredictable Charles

Wilkes, the ambitious ordnance expert John Dahlgren, the well-connected Samuel Phillips Lee, and the self-promoting and gregarious

David Dixon Porter. Lincoln was remarkably patient; he often

postponed critical decisions until the momentum of events made the consequences of those decisions evident. But Symonds also

shows that Lincoln could act decisively. Disappointed by the

lethargy of his senior naval officers on the scene, he stepped in and personally directed an amphibious assault on the Virginia coast, a successful operation that led to the capture of Norfolk.

The man who knew "little about ships" had transformed himself into one of the greatest naval strategists of his age. A unique

and riveting portrait of Lincoln and the admirals under his command, this book offers an illuminating account of Lincoln and the nation at war. In the bicentennial year of Lincoln's birth, it offers a memorable portrait of a side of his presidency

often overlooked by historians.

Recommended Reading: Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S.

Navy. From Publishers Weekly: Starred Review. Toll, a former financial analyst and political speechwriter,

makes an auspicious debut with this rousing, exhaustively researched history of the founding of the U.S. Navy. The author

chronicles the late 18th- and early 19th-century process of building a fleet that could project American power beyond her

shores. The ragtag Continental Navy created during the Revolution was promptly dismantled after the war, and it wasn't until

1794—in the face of threats to U.S. shipping from England, France and the Barbary

states of North Africa—that Congress authorized the construction of six

frigates and laid the foundation for a permanent navy. Continued below…

A cabinet-level Department of

the Navy followed in 1798. The fledgling navy quickly proved its worth in the Quasi War against France in the Caribbean,

the Tripolitan War with Tripoli and the War of 1812 against

the English. In holding its own against the British, the U.S. fleet broke

the British navy's "sacred spell of invincibility," sparked a "new enthusiasm for naval power" in the U.S. and marked the maturation of the American navy. Toll

provides perspective by seamlessly incorporating the era's political and diplomatic history into his superlative single-volume

narrative—a must-read for fans of naval history and the early American

Republic.

Recommended

Reading: Civil War Navies, 1855-1883 (The

U.S. Navy Warship Series) (Hardcover).

Description: Civil War Warships, 1855-1883 is the second in the five-volume US Navy Warships encyclopedia set. This valuable

reference lists the ships of the U.S. Navy and Confederate Navy during the Civil War and the years immediately following -

a significant period in the evolution of warships, the use of steam propulsion, and the development of ordnance. Civil War

Warships provides a wealth and variety of material not found in other books on the subject and will save the reader the effort

needed to track down information in multiple sources. Continued below…

Each ship's

size and time and place of construction are listed along with particulars of naval service. The author provides historical

details that include actions fought, damage sustained, prizes taken, ships sunk, and dates in and out of commission as well

as information about when the ship left the Navy, names used in other services, and its ultimate fate. 140 photographs, including

one of the Confederate cruiser Alabama recently uncovered by the author further contribute to this

indispensable volume. This definitive record of Civil War ships updates the author's previous work and will find a lasting

place among naval reference works.

Recommended

Reading: Naval Strategies of the Civil War: Confederate Innovations and Federal Opportunism. Description: One of the most overlooked aspects of the American Civil War is the

naval strategy played out by the U.S. Navy and the fledgling Confederate Navy, which may make this the first book to compare

and contrast the strategic concepts of the Southern Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory against his Northern counterpart,

Gideon Welles. Both men had to accomplish much and were given great latitude in achieving their goals. Mallory's vision of

seapower emphasized technological innovation and individual competence as he sought to match quality against the Union Navy's

(quantity) numerical superiority. Welles had to deal with more bureaucratic structure and to some degree a national strategy

dictated by the White House. Continued below...

The naval blockade

of the South was one of his first tasks - for which he had but few ships available - and although he followed the national

strategy, he did not limit himself to it when opportunities arose. Mallory's dedication to ironclads is well known, but he

also defined the roles of commerce raiders, submarines, and naval mines. Welles's contributions to the Union effort were rooted

in his organizational skills and his willingness to cooperate with the other military departments of his government. This

led to successes through combined army and naval units in several campaigns on and around the Mississippi River.

Recommended

Reading: Naval Campaigns of the Civil War.

Description: This analysis of naval engagements during the War Between the States presents the action from the efforts at

Fort Sumter during the secession of South Carolina in 1860, through the battles in the Gulf of Mexico, on the Mississippi

River, and along the eastern seaboard, to the final attack at Fort Fisher on the coast of North Carolina in January 1865.

This work provides an understanding of the maritime problems facing both sides at the beginning of the war, their efforts

to overcome these problems, and their attempts, both triumphant and tragic, to control the waterways of the South. The Union

blockade, Confederate privateers and commerce raiders are discussed, as is the famous battle between the Monitor and the Merrimack. Continued below…

An overview

of the events in the early months preceding the outbreak of the war is presented. The chronological arrangement of the campaigns

allows for ready reference regarding a single event or an entire series of campaigns. Maps and an index are also included.

About the Author: Paul Calore, a graduate of Johnson and Wales University,

was the Operations Branch Chief with the Defense Logistics Agency of the Department of Defense before retiring. He is a supporting

member of the U.S. Civil War Center and the Civil War Preservation Trust and has also written Land Campaigns of the Civil

War (2000). He lives in Seekonk, Massachusetts.

|