|

PREHISTORIC NATIVE PEOPLES: NATIVE AMERICANS

(Oklahoma Emphasis)

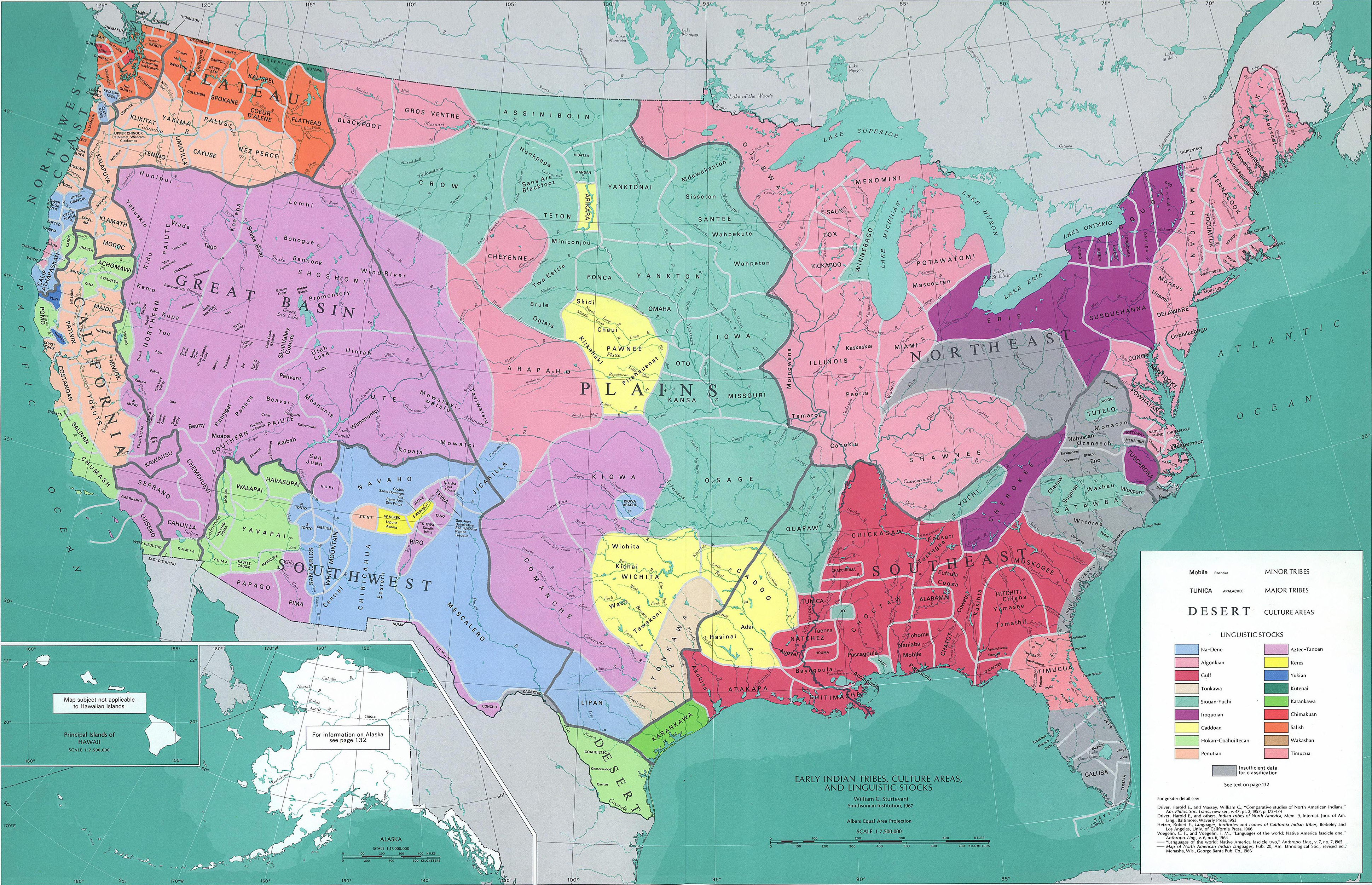

| Map of Early Native American Indian Tribes |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

(About) Large, high resolution map of early Native American Tribes. See

also map below with enhanced legend.

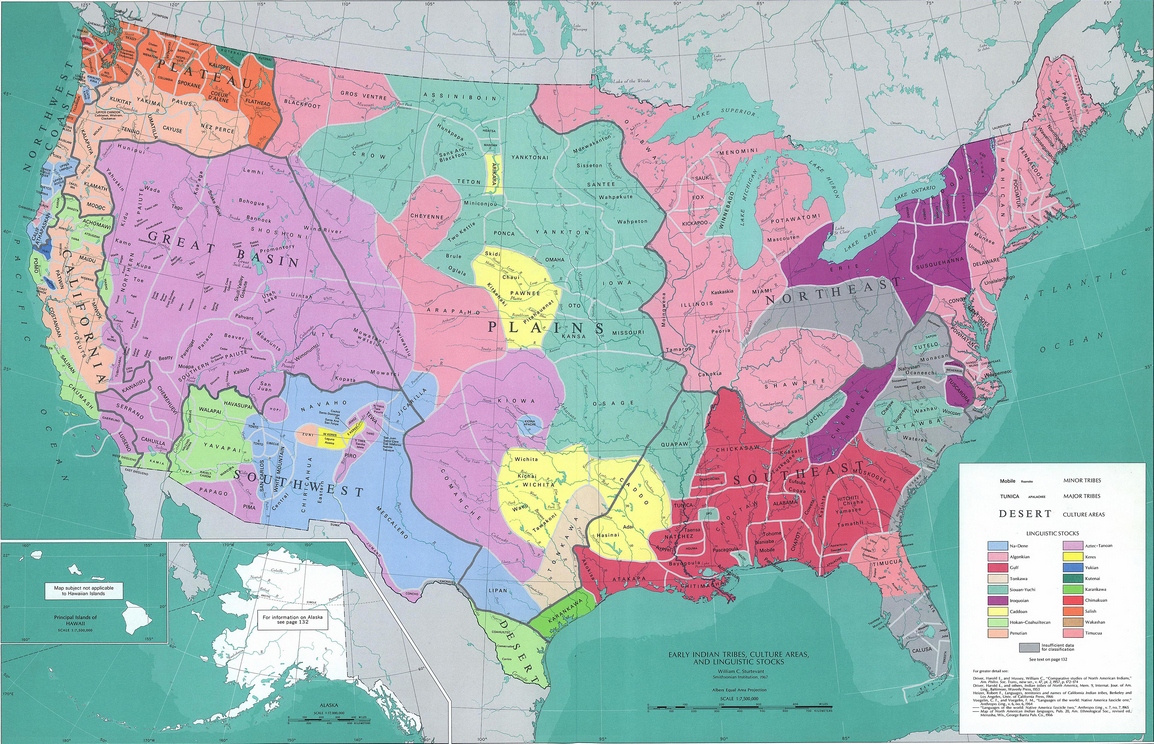

| Native American Settlement Map |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

Most Oklahomans identify with the Five Civilized Tribes, the Cheyenne, the Comanche, and other contemporary Native people of our state. Representing approximately 8

percent of Oklahoma's population, they are frequently discussed in historic accounts

of the settling of Indian Territory. However, other less-well-known Native people inhabited Oklahoma for many thousands of years prior to European arrival

on the southern plains in the mid-1500s. The Wichita and the Caddo can be traced back in prehistory at least two thousand

years, and the Osage and Apachean-speaking people can perhaps be documented here prior to the arrival of Europeans. Other

groups with no historic tribal connections may have lived here or passed through beginning some 30,000 years ago. Prehistoric

groups demonstrated remarkable adaptability to diverse settings and changing environmental conditions across Oklahoma. The

archaeological record in some 17,500 sites offers evidence for the presence of prehistoric or early historic people over an

incredible expanse of time from perhaps 30,000 years ago to as recently as the Dust Bowl era.

Within North and South America's archaeological community, a heated debate

concerns the Early Arrivals who first peopled the New World. For many years conventional wisdom held that "Clovis culture,"

existing here approximately 12,000 years ago, represented the hemisphere's initial immigrants. Scholars generally also accepted

the idea that Clovis culture was the primary pulse of early settlement. However, recent work with mitochondrial DNA as well

as historical analysis of the evolution of Native American languages brought forth suppositions that peopling of North and

South America extended back in time some 20,000 to 30,000 years ago and potentially reflected a number of separate arrivals.

The pre-Clovis argument was bolstered in southern Chile by a fourteen-thousand-year-old settlement called Monte Verde. That

it bore no resemblance to Clovis culture brought credibility to the pre-Clovis argument.

During the mid-1980s and 1990s, archaeologists reported numerous sites that

strengthened the argument for early and multiple immigrations to the new world. Identifying these sites proved fairly difficult.

Because Clovis had long been recognized as the first inhabitants, discerning exactly what would comprise a pre-Clovis site

presented a significant problem. Another issue concerned the survival of these early arrivals. Obviously, Clovis culture reflected

a successful immigration. What if some or many of these attempts 10,000 to 15,000 years prior to Clovis were failures?

Oklahoma's archaeological record has played a significant role in helping

answer at least some of the questions about Early Arrivals and pre-Clovis settlement. In two locations credible evidence for

pre-Clovis settlement exists: the 18,000-year-old Cooperton mammoth remains in Kiowa County, and the Burnham site in Woods

County with a suite of relevant radiocarbon dates ranging from 28,000 to 32,000 years ago. Both locations hold material associated

with extinct Ice Age animals. What the sites lack, however, is the clear continuity and unquestionable context found with

Clovis culture sites. Because of the uncertain context and the absence of comparable sites around Oklahoma and the region,

archaeologists have difficulty characterizing these peoples' ways of life. The Early Arrivals were explorers at the edge of

new frontiers, and their motivations, the nature of their society, and the full implications of their actions may never be

fully comprehended. Debate about the peopling of the new world will undoubtedly carry forth, each school with its ardent supporters.

Resolution of the question may 8come in the near future as dating technology becomes more precise and methodology improves.

The next period, the time of Early Specialized Hunters, refers to our earliest

well-documented inhabitants, known in the literature as the "Clovis and Folsom cultures." Clovis people occupied Oklahoma

around 11,000 to 12,000 years ago, while Folsom occurred somewhat later, around 10,000 years ago. Both are viewed as specialized

hunters, not so much for what they hunted but for manner in which they hunted. For example, Clovis groups hunted mammoths

as well as a variety of other game, whereas Folsom people specialized in hunting giant, now-extinct bison (Bison antiquus).

Stalking and killing mammoth or giant bison, large and potentially dangerous game, was not a capricious activity; it required

complex knowledge and strategy far beyond that needed for hunting deer or other modern game (with perhaps the exception of

bison). Both societies used well-designed, chipped-stone tools. Their spear points, in particular, reflect special craftsmanship.

Other weapons, tools, and possibly ornaments were made of ivory, bone, and wood. Because of the hunting emphasis, Clovis and

Folsom technology technology might not have been as expansive as that of later peoples.

The Early Specialized Hunters were nomadic groups who moved from one favorable

location to another in search of game and perhaps edible plants. In Folsom's case, their movements were very likely dictated

by bison herds' distribution and migration. Although these groups are generally thought to have lacked complex social or political

organization, some individuals (perhaps elders) must have provided information necessary for decisions about when and where

to relocate, who would participate in the hunt, and how to meet basic group needs.

Evidence for Early Specialized Hunters is sparse and widely distributed across

Oklahoma. While artifacts of Clovis people occur throughout the state, Folsom materials are restricted to the Southern Plains

or the western part of the state. Because of the great passage of time, few finds occur in a stable context; they typically

appear on eroded surfaces or are washed into river beds. Our only well-documented Clovis sites are Domebo in Caddo County,

where a group/band of these people killed an Imperial Mammoth some 11,800 years ago, and Jake Bluff in Harper County, a bison

kill. Two Folsom sites are present in Harper County in northwest Oklahoma. The Cooper and Waugh locales respectively represent

a bison kill and a possible camp. After some fifty years of searching for sites of specialized hunters, archaeologists have

discovered these four places and few other locations.

Some 10,000 years ago the environment of eastern Oklahoma was much like that

of today, and prehistoric peoples' ways of life differed considerably from those of their bison-hunting Folsom neighbors to

the west. Termed Dalton culture, these woodlands inhabitants lived in larger groups/bands, had a more expansive hunting and

collecting economy, and may also have had a somewhat more complex society. Like Folsom and Clovis, much of the evidence of

their presence comes from surface material. However, evidence from the Packard site in Mayes County, the Quince site in Atoka

County, and Billy Ross site in Haskell County point to greater use of local lithic (stone) resources, suggesting reduced mobility

and a greater range of tools, including those for plant processing.

Between approximately 9000 and 4000 years ago, various Native peoples termed

Hunters and Collectors occupied Oklahoma. Hunters and Gatherers and Late Mobile Foragers are among the designations cataloguing

these peoples in past literature. Following trends that began with Dalton culture, hunting of game continued, but emphasis

began to shift toward collecting edible plants. Although the Hunters and Collectors remained quite mobile, they were probably

less so than the more specialized hunters that had lived at the end of the ice age. Existing in an environment much like that

of our time, Hunters and Collectors moved their settlements from one seasonally available set of resources to another during

the year. Diversified resource use contributed to a more expansive inventory of weaponry and tools, especially tools related

to plant procurement. Group size was probably quite fluid, the size of the group dictated by resource availability as well

as by tasks at hand. However, this "mapping on" to seasonal availability of food resources also required greater group coordination

and undoubtedly led to increasing concentration of decision-making authority in the hands of some individuals. This era also

presents the first available evidence for concepts of an afterlife, represented by planned burial and special treatment of

deceased group members.

Ironically, the best evidence for people living during this time in Oklahoma's

past also occurs during the period of greatest climatic hardship, the Altithermal. Although a multitude of groups/cultures

existed during this five-thousand-year span, material representations of the "Calf Creek culture" have been more thoroughly

studied than other cultural complexes, perhaps due to the distinctive spear points and the people's adaptation to hot, arid

landscapes. Calf Creek people subsisted during the height of an extremely arid and seasonally warm time (circa 5000 years

ago). Their presence across Oklahoma at this time is well documented, despite harsh environmental conditions. They used large

spear points, made with craftsmanship reminiscent of Folsom hunters, as well as a tool kit geared to hunting plains-adapted

animals such as bison and antelope. Archaeologists have found Calf Creek cultural materials in many places around Oklahoma,

including the Kubik site in Kay County, the Anthony site in Caddo County, and the Arrowhead Ditch site in Muskogee County.

Calf Creek people favored high places with broad vistas, but there was also considerable diversity in the placement of settlements.

Some represent temporarily occupied camps and possible bison kill locations, and others are places where lithic raw material

is cached. Some seem to have been rendevous sites for the meeting of different bands of Calf Creek people. Still, all evidence

points to a highly nomadic, loosely organized society.

| Map of Early Native American Tribes |

|

| Map of Indian Tribes in the US |

| Map of Native American Tribes |

|

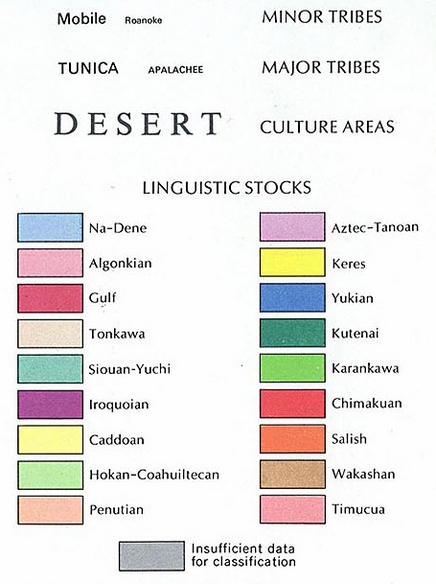

| Legend for Map of Native American Tribes |

Although we have more information on the Hunters and Collectors, their camps

and other activity sites remain scattered on the landscape, suggesting that populations were relatively low and dispersed.

Low numbers perhaps indicate small natural increases and a climate that encouraged people to seek more moderate conditions

With the end of the period of hot, dry weather, there were dramatic changes

in the context for people living in Oklahoma. Populations increased substantially, perhaps through natural increase and also

perhaps because favorable conditions encouraged migration into the region. Native peoples' settlements now became more numerous,

larger, and more permanently built.

During this time of some 4000 to 2000 years ago, significant changes occurred

in the character of prehistoric societies, and they became Hunters, Gathers, and Traders (recognized in past literature as

Foragers or occupying the Archaic Period). With the increases in population, group mobility and access to resources became

more restricted, and some of the first evidence for conflicts between societies appears. So does its alternative, exchange

or trade. Greater concern with subsistence needs led to not only greater reliance on harvesting and perhaps cultivating plants

but also to consistent storage of foods for periods of scarcity. Increased population, conflict, and plant cultivation necessitated

more complex political and social leadership. During this time religious beliefs became more visibly expressed in formal,

sometimes ritual treatment of deceased leaders and other important people. These interrelated agents of change brought about

diversification in technology as well. Weapons and tools for processing animals and plants remained in common use, although

there was a notable increase in tools for grinding seeds and nuts. Complex carbohydrates may have increasingly formed the

staple base of diet. A distinction present at this time was the presence of true ornaments, some made of bone and shell; some

may have signified greater status of the wearer.

Approximately five hundred sites offer evidence of these diverse groups. In

the eastern part of Oklahoma societies that lived north of the Arkansas River distinctly differed from those that occupied

the region south of it. Whether these groups are ethnically distinguishable is unknown. Living south of the Arkansas River

and north of the Ouachita Mountains, the "Wister culture" intensively occupied the area of Fourche Maline, San Bois, and Brazil

creeks and the Poteau and Kiamichi rivers. These people lived in what has been called "Black Midden Mounds" and appear to

have depended heavily on riverine resources.

Farther to the south, along the Red River, resided other Hunter, Gatherer,

Trader peoples. These groups are less well defined in respect to their cultural composition. To the north of the Arkansas

River existed what has been called the "Lawrence culture." In many ways they were much like their counterparts to the south.

The primary exception was the absence of the "Black Midden Mounds" and the intense settlement along the various streams and

rivers in the northeast.

Central Oklahoma also had its own localized societies at this time, ones that

were more dispersed and lived less intensively. They were more focused on plains-oriented plant and animal species. However,

in most areas they were relatively indistinguishable from their more eastern neighbors.

The situation in the west and in the Panhandle differed significantly. Here

archaeologists have found large-scale, communal bison kills and some modest camps/hamlets. Settlements are much more dispersed

and would appear much more dependent on a protein-rich diet derived from bison hunting. In the Panhandle, groups focused on

streams, rivers, and seasonally inundated playa lake beds for hunting and perhaps collection of edible plants. Important places

in this western version of Hunters, Gatherers, and Traders are the Certain Bison Kill in Beckham County, the Summers site

in Greer County, and the Muncie site in Texas County. The fewer settlements in western Oklahoma and the Panhandle may reflect

more the difference in subsistence practices than absolute numbers of people per group. However, it is likely that many more

Native peoples occupied the eastern part of the state at this time.

During the time of the Hunter, Gatherers, and Traders a stable climate permitted

groups to reestablish their presence in various regions. Rainfall increased in the next period, called Agricultural Beginnings

(circa 2000 to 1200 years ago, which previous scholarship placed in the Middle Prehistoric period or identified as Early Farmers

and in some localities as Woodland). Conditions of larger population, reduced mobility, and greater knowledge of plant cultivation

catalyzed the true beginnings of agriculture. It is interesting, if not somewhat paradoxical, however, that Agricultural Beginnings

may have started earlier in the west and central regions of Oklahoma than in the east, where populations were greater. Perhaps

in southeastern Oklahoma societies could ignore plant cultivation because of the abundant resources of stream and river valleys.

Throughout the state populations are thought to have continued some type of geometric population growth, along with decreasing

mobility and an even greater dependence on edible plants. Social, political, and religious changes born during the prior time

of Hunters, Gatherers, and Traders (conflict, social complexity, and religious practices) became more expressed and more widespread.

Native groups continued to build and use storage facilities and constructed more permanent dwellings.

More importantly, three particularly significant technological innovations

during Agricultural Beginnings set the stage for future evolutionary trajectories. The bow and arrow radically changed two

social practices, hunting and conflict. Groups no longer had to gather for a collective hunt; hunters could go forth in groups

of two to three and with the extended range of the bow still have a profitable hunting expedition. The bow and arrow also

further enabled conflict, fostering increased mortality when opposing groups met. Development of pottery permitted two new

concepts, a more permanent, secure means of storage and a new means of preparing foods. The new technology included adoption

and improvement of axes and adzes for forest clearing and framing wooden structures. The manufacture of specialized goods

for social and religious purposes also continued.

The number of places containing expressions of these Agricultural Beginnings

groups is greater than those for the preceding period, although not excessively so. Probably fewer than a thousand such sites

have been documented. The pattern follows that identified for Hunters, Gatherers, and Traders, in respect to a north-south

and east-west distinction. In eastern Oklahoma the Arkansas River again served as a boundary between cultural groups. To the

north, in Delaware and Mayes counties, lived a distinct people, termed the "Cooper culture," that have relationships to groups

occupying the Kansas City, Missouri, area some 1500 years ago. While the Kansas societies built mounds where their leaders

were buried, no such earthworks have been found in Oklahoma. Thus, relationships to the Kansas groups are demonstrated in

styles of spear points, ceramics, and clay figurines. Other indigenous groups also apparently lived in the area contemporaneously

with the Cooper people. Both groups in northeastern Oklahoma used a number of rock shelters as seasonal camps.

South of the Arkansas River and north of the Ouachita Mountains lived the

Fourche Maline, a continuation of the Wister culture. The two life styles were very much alike, but the Fourche Maline people

made important technological advancements with the bow and arrow, ceramics, and stone tools used in woodworking. Fourche Maline

continued to occupy the "Black Midden Mound" locations, and their economy revolved around riverine resources. Along the Red

River, other less well-defined cultures followed similar ways of life.

In central Oklahoma, within a mixed zone of tall-grass prairies and woods

of blackjack and post oak, there also existed some distinctions between Native groups in the north and in the south. In north-central

Oklahoma, particularly in the Arkansas River valley in Kay and Osage counties, some societies had technological characteristics

of the Kansas City people, generally in spear point and pottery styles. Archaeologists have found this cultural expression

at sites such as Hammons, Hudsonpillar, and Daniels in Kay County. Other groups of roughly contemporaneous settlements manifested

material culture more consistent with local developments and are thought to represent continuation from the previous Hunters,

Gatherers, and Traders. Examples of these camps and hamlets include Von Elm and Vickery in Kay County as well as a few rock

shelters in Osage County. Both groups of Native peoples made substantial use of plains-adapted plants and animals. However,

these communities were probably diminished when rainfall increased and woodland encroached. In south-central Oklahoma other

societies during Agricultural Beginnings lived in dispersed settlements, frequently on sandy terraces high above the alluvial

valleys. Examples of occupations sites are Barkheimer in Seminole County, Gregory in Pottawatomie County, and Ayers in Marshall

County. Due to the tremendous deposition of flood-borne soils, valley occupations are rarely found. Unlike their counterparts

in other regions, these groups did not display as much evidence for decreased mobility and duration of stay. These south-central

groups paralleled other Native peoples in their adoption of the bow and arrow, ceramics, and tools for woodworking.

The western part of Oklahoma exhibited the greatest variability in Agricultural

Beginnings. Some groups continued the communal bison hunts of Hunters, Gatherers, and Traders. In fact, these Native peoples

may have changed little during the ensuing 1000 years. They continued to use well-made spear points to hunt bison and other

game, and they potentially remained fairly nomadic. The Certain bison kill in Beckham County reflects this continuation. However,

other groups had a more diverse orientation, hunting bison as well as other animals and collecting edible plants. These people

used bows and arrows rather than spears and stored and prepared foods in pottery vessels. The Swift Horse locality in Roger

Mills County is one of the best examples of this way of life. The pronounced difference in social and economic patterns in

western Oklahoma was not always accommodated and occasionally led to conflict.

Little cultural information exists for most of the Oklahoma Panhandle. However,

in Cimarron County Native groups occupied a number of dry shelters during this period. These caves and shelters contained

a wealth of information on these people's material culture of the people as well as on their counterparts in others regions.

Objects collected from these camping sites consist of quantities of perishable items including woven sandals, rabbit-skin

bags, woven bags, throwing sticks, and foreshafts of spears.

Between 1200 and 550 years ago, Oklahoma was occupied by numerous societies

of Native Americans called Agricultural Villagers who lived in settled communities and farmed. Known in some earlier literature

as occupying the Late Prehistoric Period or as Village Farmers, these varied peoples continue the pattern that started during

the Agricultural Beginnings period. Throughout much of the state, they lived in well-built, grass-roofed houses with vertically

set, wooden-post walls plastered with mud. The exception occurred in the Panhandle, where houses were made with stone-slab

walls or were dug below the ground surface ("pit houses"). Strategically placed near highly fertile soils but outside of danger

from floods, settlements ranged from only a few houses (farmsteads/hamlets) to large villages of twenty or more. In some instances

villages demonstrated evidence of a planned layout. At any given time, a village might accommodate up to two hundred persons.

Population rapidly accelerated during this time, bringing about not only greater community size but also greater density of

settlement. In some areas villages might occur as frequently as a mile and half-apart along favored stretches of river valley.

In eastern Oklahoma another important architectural practice, in addition to housing, was the construction of a variety of

earthen mounds. Some were temple mounds where priestly leaders resided, and others were burial mounds for political and religious

leaders. In the central and western parts of Oklahoma archaeologists have found no mound construction, but this does not mean

that the societies necessarily lacked religious complexity.

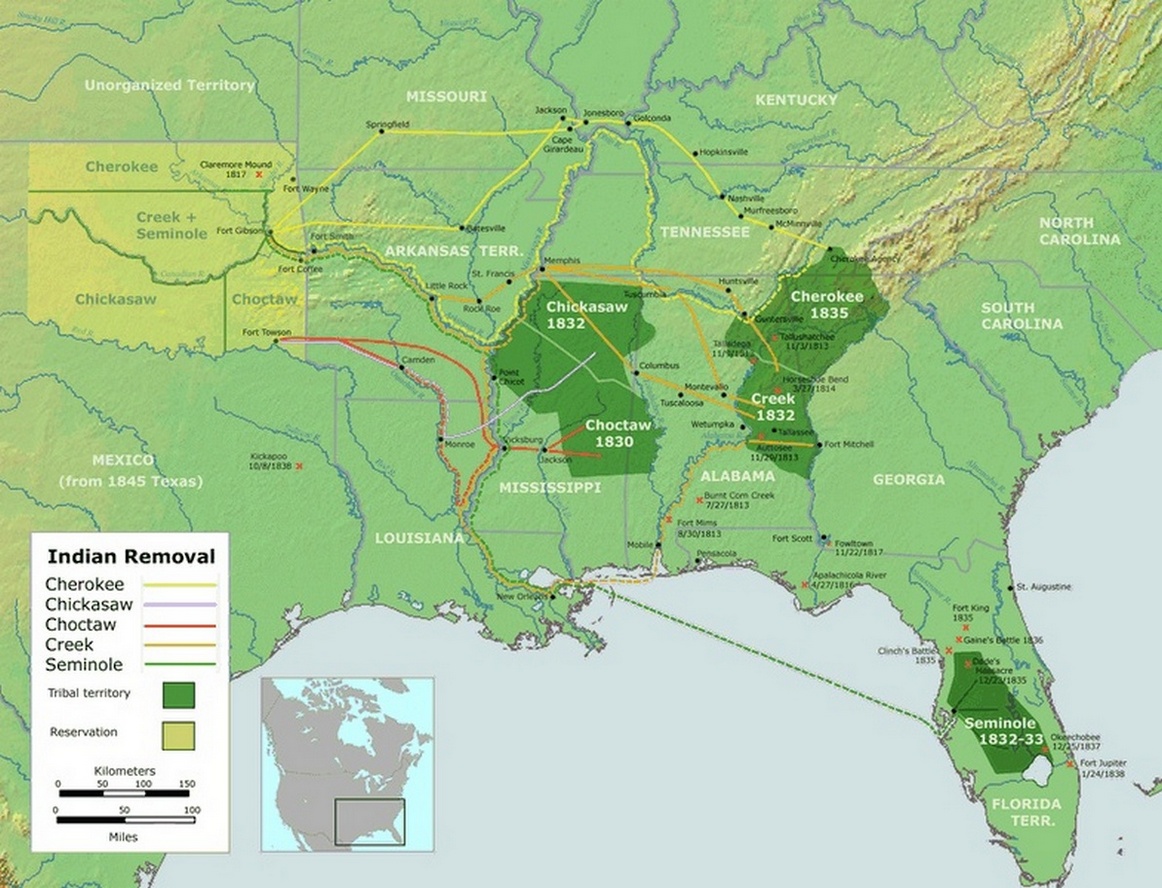

| Map of Prominent Native American Tribes |

|

| Map of forced relocation of Five Civilized Native American Tribes |

(Map) Of the hundreds of Native American tribes that inhabited the

Northern Hemisphere by 1800, only a handful would be viewed with reluctant acceptance by Europeans who had settled the land

en masse. By the mid-19th century there were five tribes that had adopted many ways of the neighboring

European settlers, and were therefore referred to as the Five Civilized Tribes. Although considered civilized, the Five Tribes

were considered by Washington as incompatible with nearby white settlements. Through a series of 19th century

Indian removal acts enacted by politicians at the nation's capitol, each of the five tribes would be forced to cede land

continually until they were collectively removed and herded onto reservations on what was known as Indian Territory.

The reservations were located on what Washington considered barren, waste land unsuited for white settlement and yet land far

enough west to allow a buffer or neutral ground between whites and Indians. The Mid West, including Indian Territory, however,

would soon succumb to Manifest Destiny as European settlers pushed west settling new land. Present-day Oklahoma masks

or overlays much of the former Indian Territory. With the prospect of gold and silver out west, coupled with the Homestead

Act, white encroachment on the reservations, the long promised lands for peace, would quickly force Native American

assimilation with whites, again. Today, the five reservations are merely swaths of land within the State of Oklahoma.

Although America's Indigenous peoples would see African-Americans become citizens with ratification of the 14th Amendment

in 1868, the land's original inhabitants would wait until the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act to be extended the same right.

During the past 750 to1000 years, subsistence also markedly changed. People

increasingly emphasized certain edible plants in the diet, and plant domestication efforts expanded. By the time of Agricultural

Villagers, tropical plants such as corn, beans, and squash as well as native species such as chenopodium, amaranth, marshelder,

sumpweed, and sunflower were domesticated. By the late thirteenth century farming was a major enterprise, requiring field

maintenance as well as coordination of field placement between different societies. Hunting continued as well, and a diversity

of animals supplemented a carbohydrate-laden diet. In fact, some of the elite leaders of groups in eastern Oklahoma preferred

to eat an alternative, healthier diet high in proteins and wild plants, rather than corn. In the west, Agricultural Villagers

who were adapted to a plains environment invested much effort in hunting of bison and other plains animals. In the Agricultural

Villagers period, technology, already highly sophisticated, expanded even more. The bow and arrow became a mainstay for hunting

as well as a weapon in conflicts between groups. Because of the agricultural emphasis, stone tools, like grinding stones and

basins for processing corn and other grains, proliferated. On the plains, agricultural activity brought into use numerous

bone tools, including bison-bone hoes and digging sticks. Other bone items functioned as awls/needles, scrapers, beads, breastplates,

and even whistles. While it had been only nominally decorated and had a minimum of forms during the preceding period, in the

Agricultural Villagers period pottery exploded into a multiplicity of forms and stylistic expressions. Bowls, jars, plates,

bottles, and effigy forms have been found. Decoration on vessels included incising, engraving, punctation, applique, as well

as polishing. Pottery color no longer resulted from simple differences in firing. Slips were used to color the vessels, and

glazes were used to change the character of the external and internal surfaces. Other mediums for material culture, including

copper, crystal, and a variety of minerals for ornaments, also express this evolutionary acceleration. Textiles were widely

used, but the difficulty of preserving these fragile materials limits a knowledge of the extent of use. Of particular note

in technology is an increasing use of material goods in expressing ritual and religious concepts.

The political, social, and religious systems of Native peoples likewise became

more complex and were manifested in physical symbols such as mounds and special structures, especially in eastern Oklahoma.

Population expansion and dramatically increased reliance on agriculture brought greater need for more strategically organized

society. In general, dependence on agriculture also caused more involvement with religious practitioners to support and maintain

a system. However, it must be noted that an absence of a visual evidence of religious complexity does not necessarily mean

that groups were not complex; it may mean that the people did not demonstrate religious belief in a visible way.

Because of the increase in the number of settlements as well as their proximity

to modern times, thousands of Village Agriculturalist occupation sites have been documented, especially in the Arkansas and

Red river drainage systems. For some 650 years these people followed a life way adapted to an agricultural economy. At the

same time, they developed a religious system tied to the lives and deaths of their priestly elite rulers. Mounds visually

expressed their beliefs.

These people were of the Caddoan tradition. Along the Arkansas River and its

major tributaries they built a number of important mound centers including Harlan in Cherokee County, Norman in Wagoner County,

and the most well known, Spiro in Le Flore County. Other smaller mound centers as well as populous settlements surrounded

these centers of religious activity. Along the Red River and its associated streams occurred a similar set of important mound

centers: Woods Mound Group, Clements, Baldwin, and Grobin Davis mound group in McCurtain County, and the Nelson Mound in Choctaw

County. As in the Arkansas drainage, in the Red River drainage the Caddoan mound centers were the religious focus for surrounding

hamlets and villages. Both Caddoan societies made wide use of decorated pottery vessels and maintained an expansive inventory

of domestic goods and status ornaments.

In south-central and western Oklahoma lived Agricultural Villagers of the

Redbed Plains tradition. Occupying sizeable settlements along the Washita, Canadian, and North Canadian rivers and the forks

of the Red River as well as their feeder streams, these Native peoples practiced an intensive agriculture adapted to southern

plains conditions. The intensity of farming practices exceeded that of their eastern counterparts. Their technology extensively

used bison bone for agricultural tools. Domestic items such as pottery were less decorated than those found in the east. However,

there was sophistication in the simplicity of their design of tools and ornaments. For example, sandstone abraders used in

making bone tools were graded by coarseness, like modern grades of sandpaper. Important sites of the Redbed Plains are Arthur

in Garvin County, Heerwald in Custer County, and McLemore in Washita County.

In the Oklahoma Panhandle there existed people of the "Antelope Creek culture."

This term refers to Native groups that lived along the upper reaches of the Canadian, North Canadian, and Arkansas rivers.

Unlike other Agricultural Villagers, they built settlements of stone slab walled houses much like those in the southwest.

Their ways of life paralleled those of the Redbed Plains villagers tradition. They maintained an economy based on agriculture

and on bison obtained on long-distance, seasonal hunts.

Other groups of this period were affiliated with the Odessa Yates settlement.

In the Panhandle region some 700 years ago at Odessa Yates and other nearby sites, local Native people lived in subterranean

structures or pit houses. An agricultural subsistence pattern encompassed an extensive trade economy with other late prehistoric

societies living in New Mexico. The technology of these groups was much like those of surrounding Antelope Creek settlements.

Additionally, they maintained a pottery tradition more similar to that of peoples of western Kansas and different from that

of other areas of the southwest and the Oklahoma Panhandle.

The Agricultural Villagers period marks the first time when prehistoric groups

can also be linked to historically known Native societies (or "tribes:"). It preceded a new era that brought many turbulent

changes and transformed groups in Oklahoma and elsewhere.

The next period, that of Coalesced Villagers/Communal Hunters, just prior

to a historically known past, reflects incredible changes in Native societies (in previous literature akin to the Transitional

Late Prehistoric Period and Early Historic Buffalo Hunters). The times changed some Native groups from settled Agricultural

Villagers to nomadic, communal bison hunters in a short span of fifty to one hundred years. The years between roughly 550

and 200 years ago have also been termed protohistory, a time before a well-documented written and visual record of the past.

Many and profound changes marked the beginning of Coalesced Villagers/Communal Hunters.

The late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries continued a cycle of drought

conditions that had begun back in the thirteenth century. However, now the drought was accompanied by significantly cooler

temperatures, causing some scholars to term this the "Little Ice Age." Colder temperatures especially shortened the growing

season and may have caused many groups to abandon agriculture or to scale back its intensity. Of course, these same conditions

fostered massive bison herds and led to even greater predation on the bison by plains-adapted groups.

In this period new people came to Oklahoma and the surrounding region, upsetting

the delicate balance among groups in Oklahoma and the Southern Plains. Native peoples were forced south out of the Rocky Mountains,

the Basin Plateau range, and the northern plains. The arrival of the Kiowa, Apache, Comanche, and somewhat later, the Cheyenne

and Arapaho created new societal dynamics throughout the area. However, the greatest challenge came with the arrival of Europeans.

Arriving in the mid-sixteenth century, Europeans brought many new elements,

drastically altering the economies, political and religious systems, and basic ways of life of Native peoples. Foremost among

these elements was disease. Measles, smallpox, and diphtheria nearly destroyed some "tribes" forcing survivors to join with

other groups. Because of their more sedentary lifestyle, the Coalesced Villagers suffered more devastation from disease than

did the Communal Hunters. Europeans also brought material goods, further altering Native society. The horse changed the nature

of hunting as well as warfare. In combination with firearms, it revolutionized groups such as the Comanche, transforming them

into "the warlords of the plains." Europeans used trade to pit one Native group against another and also tried to force the

Christian religion on Native people. Against this background of turmoil, it is not surprising that the archaeological record

of this period is poorly documented and even more poorly understood.

As suggested above, two different patterns of life ways existed during this

time. Some groups formed Coalesced Villages, living much like their Agricultural Villagers ancestors. However, the villages

were much larger, holding perhaps five hundred to one thousand inhabitants. There is historic documentation to indicate that

villages were seasonally abandoned while the occupants pursued bison herds for two to three months. Some villagers groups

were highly mobile, maintaining portable dwellings (e.g., tipis) while following the bison herds across the plains. But even

the Coalesced Villagers settlements exhibited less permanency than during the preceding period. For example, groups of the

Wichita abandoned rectangular houses with mud/clay plastered walls in favor of circular grass houses. Throughout much of the

region nondomestic architecture (e.g., mounds) construction was discontinued, although societies of the Caddo Confederacy

continued to build mounds in Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and extreme southeastern Oklahoma.

In the Coalesced Villagers/Communal Hunters period, the new economic specialization

was expressed through technology. There was an increased emphasis on weaponry and hunting/processing of bison. Of particular

note are large scrapers used in working hides, which were traded to the French, Spanish, and Americans. With the shift to

greater emphasis in communal hunting, agricultural technology remains consistent with that found during the Agricultural Villagers

period, although at lessened intensity. The principal technological change lay in the use and accommodation of European goods.

Ornaments such as glass beads and metal bracelets and rings became items of status. Domestic goods such as metal hatchets,

axes, knives, and firearms were used in a functionally consistent fashion. There were other goods, however, such as metal

kettles and pots, that were hammered out as arrow points, knives, and scrapers, the original shape and function being accommodated

to new forms and tasks. Meanwhile, Native domestic goods such as chipped stone tools (used as weapons and in the hunting and

butchering of game), pottery vessels, and bone tools and ornaments continued to be used. Replacement of many of these items

by goods of European manufacture would not be common until the 1800s.

Although settlement, subsistence, and technology changed rapidly, the social,

political, and religious systems were even more profoundly affected. Because European diseases caused great population reduction,

societies endured large-scale realignment. Equally significant changes in political structure occurred because of pressure

from European governments, which embodied a centralized leadership system with a governor or other singular figure in control.

Diplomacy required Native societies to designate an individual to function in a like capacity, even though this form of political

organization was totally alien to their own form of decision making. The interaction of Europeans with various tribes and

in some cases, their marriage to tribe members, also caused considerable disruption in Native society. The other major area

of European intervention into Native people's life ways came in the area of religion. Here, Christianity was impressed upon

Native societies with the intent of eradicating tribal beliefs. Many Native groups tried to accommodate a new religious order

while still treating their traditional religious leaders with the appropriate respect. In some situations this resulted in

the abandonment of traditional religious practices and substitution of European ritual.

While thousands of locations contain evidence of Agricultural Villagers, a

much smaller number of places provide evidence of Coalesced Villagers/Nomadic Communal Hunters. Fewer than one hundred sites

are proven as occupied either immediately prior to European contact or within 250 years of it. The best evidence for the configuration

of pre-European Native societies exists in western Oklahoma. Throughout the western one half of Oklahoma, the "Wheeler culture"

people lived at a number of village sites along tributary streams of the Washita or North Fork of the Red River. Some villages

such as Edwards in Beckham County and Duncan in Washita County were fortified. Others in Caddo, Custer, and Canadian counties

apparently had no such protection. There was some specialization by village: the more western may represent locations that

were residentially used in seasonal bison hunts. Those further east, like Little Deer in Custer County and Scott in Canadian

County, display no indications of palisades or other defensive architecture. Settlements of this time are probably related

to various subgroups of the Wichita. Occupation continued until about 350 years ago. Following this, an even more restricted

sample of villages, including the Deer Creek (Fedinandina) location in Kay County, Longest village in Jefferson County, Devil's

Canyon in Kiowa County, and Lasley Vore rendezvous locality in Tulsa County, can be specifically linked by historic accounts

to various Wichita subgroups. These sites also represent the only known places where archaeological evidence firmly establishes

contact between Europeans and Native peoples.

Following the Coalesced Villagers/Communal Hunters period, Native societies

entered a time of even greater complexity with respect to culture change and interaction with Europeans. This is the 1830s,

the time when many Southeastern tribes and groups were moved from the Midwest and Plains to Oklahoma. Well documented, this

period is better addressed through the historical record. The story of prehistoric peoples' occupation of Oklahoma is a lengthy

journey through time, one that is expressed with increasingly complex conditions of increases in population, diversification

in technology, a more productive subsistence base, greater engineering skill in building, and different and more complex social,

political, and religious beliefs. Time also holds witness to declines in society brought about by environmental conditions,

the appearance of new Native groups in the region, and the arrival of Europeans. Thus, the Native peoples that are historically

recognized in some ways bear little resemblance to their predecessors of the prehistoric past.

(Related reading and sources listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended Reading: 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Description: 1491 is not so much the story of a year, as of what that year stands for: the long-debated (and often-dismissed)

question of what human civilization in the Americas

was like before the Europeans crashed the party. The history books most Americans were (and still are) raised on describe

the continents before Columbus as a vast, underused territory,

sparsely populated by primitives whose cultures would inevitably bow before the advanced technologies of the Europeans. For

decades, though, among the archaeologists, anthropologists, paleolinguists, and others whose discoveries Charles C. Mann brings

together in 1491, different stories have been emerging. Among the revelations: the first Americans may not have come over

the Bering land bridge around 12,000 B.C. but by boat along the Pacific coast 10 or even 20 thousand years earlier; the Americas

were a far more urban, more populated, and more technologically advanced region than generally assumed; and the Indians, rather

than living in static harmony with nature, radically engineered the landscape across the continents, to the point that even

"timeless" natural features like the Amazon rainforest can be seen as products of human intervention. Continued below...

Mann is well

aware that much of the history he relates is necessarily speculative, the product of pot-shard interpretation and precise

scientific measurements that often end up being radically revised in later decades. But the most compelling of his eye-opening

revisionist stories are among the best-founded: the stories of early American-European contact. To many of those who were

there, the earliest encounters felt more like a meeting of equals than one of natural domination. And those who came later

and found an emptied landscape that seemed ripe for the taking, Mann argues convincingly, encountered not the natural and

unchanging state of the native American, but the evidence of a sudden calamity: the ravages of what was likely the greatest

epidemic in human history, the smallpox and other diseases introduced inadvertently by Europeans to a population without immunity,

which swept through the Americas faster than the explorers who brought it, and left behind for their discovery a land that

held only a shadow of the thriving cultures that it had sustained for centuries before. Includes outstanding photos and maps.

Recommended

Viewing: 500 Nations

(372 minutes). Description: 500 Nations is an eight-part documentary (more than 6 hours and that's not including its interactive CD-ROM

filled with extra features) that explores the history of the indigenous peoples of North and Central America, from pre-Colombian

times through the period of European contact and colonization, to the end of the 19th century and the subjugation of the Plains

Indians of North America. 500 Nations utilizes historical texts, eyewitness

accounts, pictorial sources and computer graphic reconstructions to explore the magnificent civilizations which flourished

prior to contact with Western civilization, and to tell the dramatic and tragic story of the Native American nations' desperate

attempts to retain their way of life against overwhelming odds. Continued below...

Mention the

word "Indian," and most will conjure up images inspired by myths and movies: teepees, headdresses, and war paint; Sitting

Bull, Geronimo, Crazy Horse, and their battles (like Little Big Horn) with the U.S. Cavalry. Those stories of the so-called

"horse nations" of the Great

Plains are all here, but so is a great deal more. Using impressive computer imaging, photos, location film footage

and breathtaking cinematography, interviews with present-day Indians, books and manuscripts, museum artifacts, and more, Leustig

and his crew go back more than a millennium to present an fascinating account of Indians, including those (like the Maya and

Aztecs in Mexico and the Anasazi in the Southwest) who were here long before white men ever reached these shores.

It was

the arrival of Europeans like Columbus, Cortez, and DeSoto that marked the beginning of the end for the Indians. Considering

the participation of host Kevin Costner, whose film Dances with Wolves was highly sympathetic to the Indians, it's no bulletin

that 500 Nations also takes a compassionate view of the multitude of calamities--from alcohol and disease to the corruption

of their culture and the depletion of their vast natural resources--visited on them by the white man in his quest for land

and money, eventually leading to such horrific events as the Trail of Tears "forced march," the massacre at Wounded Knee,

and other consequences of the effort to "relocate" Indians to the reservations where many of them still live. Along the way,

we learn about the Indians' participation in such events as the American Revolution and the War of 1812, as well as popular

legends like the first Thanksgiving (it really happened) and the rescue of Captain John Smith by Pocahontas (it probably didn't).

Recommended

Reading: Atlas of the North

American Indian. Description: This unique resource covers the entire history, culture, tribal

locations, languages, and lifeways of Native American groups across the United States,

Canada, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean. Thoroughly updated, Atlas of the

North American Indian combines clear and informative text with newly drawn maps to provide the most up-to-date political and

cultural developments in Indian affairs, as well as the latest archaeological research findings on prehistoric peoples. The

new edition features several revised and updated sections, such as "Self-Determination," "The Federal and Indian Trust Relationship

and the Reservation System," "Urban Indians," "Indian Social Conditions," and "Indian Cultural Renewal." Continued below...

Other updated

information includes: a revised section on Canada, including Nunavut, the first new Canadian territory created since 1949,

with a population that is 85% Inuit; the latest statistics and new federal laws on tribal enterprises, including a new section

on "Indian Gaming"; and current information on preferred names now in use by certain tribes and groups, such as the use of

"Inuit" rather than "Eskimo."

NEW!

Recommended Viewing: We Shall Remain (PBS) (DVDs) (420 minutes). Midwest Book Review: We Shall Remain is a three-DVD thinpack set

collecting five documentaries from the acclaimed PBS history series "American Experience", about Native American leaders including

Massasoit, Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa, Major Ridge, Geronimo, and Fools Crow, all who did everything they could to resist being

forcibly removed from their land and preserve their culture. Continued below…

Their strategies

ranged from military action to diplomacy, spirituality, or even legal and political means. The stories of these individual

leaders span four hundred years; collectively, they give a portrait of an oft-overlooked yet crucial side of American history,

and carry the highest recommendation for public library as well as home DVD collections. Special features include behind-the-scenes

footage, a thirty-minute preview film, materials for educators and librarians, four ReelNative films of Native Americans sharing

their personal stories, and three Native Now films about modern-day issues facing Native Americans. 7 hours. "Viewers will

be amazed." "If you're keeping score, this program ranks among the best TV documentaries ever made." and "Reminds us that

true glory lies in the honest histories of people, not the manipulated histories of governments. This is the stuff they kept

from us." --Clif Garboden, The Boston Phoenix.

Recommended

Reading: Native American Weapons. Review From Library Journal: In this taut and generously illustrated overview, Taylor (Buckskin and Buffalo: The Artistry of

the Plains Indians) zeroes in on North American Indian arms and armor from prehistoric times to the late 19th century, dividing

his subject into five efficient categories. The chapter on striking weapons covers war clubs and tomahawks, cutting weapons

include knives from Folsom stone to Bowie, piercing weapons comprise spears and bows and arrows, and defensive weapons feature

the seldom-emphasized armor both men and horses wore in battle. Most interesting, however, is the chapter on symbolic weapons,

which describes how powerful icons on dress or ornament were used to ward off blows. The illustrations mostly color photos

of objects help the reader see distinctions between, for example, a regular tomahawk and a spontoon or French one. Continued below...

Old paintings

and photographs show the weapons held by their owners, giving both a time frame and a sense of their importance. The text

is packed and yet very readable, and the amount of history, tribal distinction, and construction detail given in such a short

book is astounding. This excellent introduction is a bargain for any library. Featuring 155 color photographs and illustrations,

Native American Weapons surveys weapons made and used by American Indians north of present-day Mexico

from prehistoric times to the late nineteenth century, when European weapons were in common use. Colin F. Taylor skillfully

describes the weapons and their roles in tribal culture, economy, and political systems. He categorizes the weapons according

to their function--from striking, cutting, and piercing weapons to those with defensive and even symbolic properties, and

he documents the ingenuity of the people who crafted them. Taylor

explains the history and use of weapons such as the atlatl, a lethal throwing stick whose basic design was enhanced by carving,

painting, or other ornamentation. The atlatl surprised De Soto's

expedition and contributed to the Spaniards' defeat. Another highlight is Taylor's

description of the evolution of body armor, first fashioned to defend against arrows, then against bullets from early firearms.

Over thousands of years the weapons were developed and creatively matched to their environment--highly functional and often

decorative, carried proudly in tribal gatherings and in war.

Recommended

Reading: North American

Bows, Arrows, and Quivers: An Illustrated History. Description: Otis Tufton Mason, the founder of the Anthropologist Society of Washington, details

the history of the archery tools used by the native peoples throughout the North American continent. Hundreds of precise line

drawings showcase the many varieties of bows, arrows, and quivers they crafted, and beautifully rendered images display tools

and materials. Sketched diagrams demonstrate exactly how the arrow points were mounted and the bows assembled. Nearly all

the illustrations are accompanied by an explanatory page of authoritative information, and Mason’s writing reveals his

deep appreciation and admiration of the work he’s presenting and the people who created it.

Recommended

Reading: Encyclopedia of American Indian

Contributions to the World: 15,000 Years of Inventions and Innovations (Facts on File Library of American History)

(Hardcover). Editorial Review from Booklist: More than 450 inventions and innovations that can be traced to

indigenous peoples of North, Middle, and South America are described in this wonderful encyclopedia.

Criteria for selection are that the item or concept must have originated in the Americas,

it must have been used by the indigenous people, and it must have been adopted in some way by other cultures. Continued below...

Some of the

innovations may have been independently developed in other parts of the world (geometry, for example, was developed in ancient

China,

Greece, and the Middle East as well as in the Americas) but still fit all three criteria. The period of time covered is 25,000

B.C. to the twentieth century. Among the entries are Adobe, Agriculture, Appaloosa horse breed, Chocolate, Cigars, Diabetes

medication, Freeze-drying, Hydraulics, Trousers, Urban planning, and Zoned biodiversity. Readers will find much of the content

revealing. The authors note that the Moche "invented the electrochemical production of electricity" although they used it

only for electroplating, a process they developed "more than a thousand years" before the Europeans, who generally get the

credit. The Aztec medical system was far more comprehensive than anything available in Europe

at the time of contact.

The Encyclopedia

of American Indian Contributions to the World

is an "Eyeopener to the innumerable contributions of the American Indian to our nation and to world civilizations...."

The awards

it has won and some of the print reviews this book has received are listed below.

Winner 11th Annual Colorado

Book Award, Collections and Anthologies

Winner Wordcraft

Circle of Native Writers and Storytellers Writer of the Year, Creative Reference Work, 2002

Selected by Booklist as Editors Choice Reference Source,

2002

"This is a well-written book with fascinating information

and wonderful pictures. It should be in every public, school, and academic library for its depth of research and amazing wealth

of knowledge. We've starred this title because it is eye-opening and thought-provoking, and there is nothing else quite like

it." Booklist Starred Review

"[An] interesting, informative, and inspiring book." Native

Peoples Magazine

"I would strongly urge anyone with a kernel of intellectual

curiosity: teacher, administrator, researcher, lawyer, politician, writer, to buy this book. I guarantee it will enlighten,

stimulate and entertain...Native students and indigenous instructors must obtain their own copies of the Encyclopedia. Whether

Cree, Mayan or Penobscot they will find a deep source of pride on each and every page. I can well imagine the excitement of

Native teachers when they obtain the book followed by an eagerness to share its contents with everyone within reach."

"I hope the Encyclopedia will serve as the basis for an

entirely new approach to Native history, one in which the scholar is liberated from the anti-Indian texts of the recent past.

Ideally, a copy of the Encyclopedia should be in every class in every school across the hemisphere." Akwesasne Notes-Indian

Time–Doug George-Kanentiio, Akwesasne Mohawk, co-founder of the Native American Journalists Association and the Akwesasne

Communications Society

"Highly recommended for academic libraries keeping collections

about American Indians." Choice: Current Reviews for Academic Libraries

"Native accomplishments finally get their due in this award-winning

book." American Indian Report

"A treasure trove of information about the large range

of technologies and productions of Indian peoples. This is indeed the most comprehensive compilation of American Indian inventions

and contributions to date. It is most worthwhile and should be on the bookshelves of every library and home in America." Indian Country Today

"This large, well-illustrated volume is an excellent reference.

One of the important strengths of the encyclopedia is that the information provided is balanced and rooted in facts, not speculation.

Highly recommended." Multicultural Review

"Far from the stereotypical idea that Native Americans

were uncultured and simple, possessing only uncomplicated inventions such as bows and arrows or canoes, these varied cultures

donated a rich assortment of ideas and items to the world. This book can be recommended to libraries that support an interdisciplinary

approach to student learning, such as units that integrate biology and culture studies projects." VOYA: Voice of Youth Advocates

"...a comprehensive, unique A to Z reference to the vast

offerings made by the American Indians throughout history." Winds of Change (American Indian Science and Engineering Society)

"We bought

one for each center. It is a GREAT resource." Ann Rutherford, Director Learning Resources Center,

Oglala Lakota College

"As I travel

to conferences and host presentations, I take your book as a reference and to show individuals. It allows science, engineering

and math students to gain insight into the traditional knowledge held about these and related subjects. I believe it empowers

them to know this knowledge is already within. To balance contemporary knowledge within that context creates a student who

can experience a topic from a number of perspectives." Jacqueline Bolman, Director, South Dakota School of Mines & Technology

Scientific Knowledge for Indian Learning and Leadership (SKILL)/NASA Honors Program

"…the

three page introduction alone makes this book a valuable resource as it sets forth the circumstances which led the invaders

to change their initial writings of wonder at the advanced native societies…I hope a way can be found to put this book

in the hands of our youth and all who touch them." Carter Camp, American Indian rights activist, Ponca tribal leader and founder

of Kansas/Oklahoma AIM

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Robert E. Bell, ed., Prehistory of Oklahoma (Orlando, Fla.:

Academic Press, 1984). Leland C. Bement, Bison Hunting at Cooper Site: Where Lightning Bolts Drew Thundering Herds (Norman:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1999). James A. Brown, The Spiro Ceremonial Center, Memoirs of the Museum of Anthropology 29

(Ann Arbor, Mich.: Museum of Anthropology Publications, 1996). Thomas D. Dillehay, The Settlement of the Americas (New York:

Basic Books, 2000). Brian M. Fagan, Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent (London, England: Thames and Hudson,

1995). Claudette Marie Gilbert and Robert L. Brooks, From Mounds to Mammoths: A Field Guide to Oklahoma Prehistory (2d ed.,

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000). Waldo Wedel, Prehistoric Man on the Great Plains (Norman: University of Oklahoma

Press, 1961). Don G. Wyckoff and Robert L. Brooks, Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective, Archeological Resource Survey

Report No. 16 (Norman: Oklahoma Archeological Survey, 1981).

Robert L. Brooks

© Oklahoma Historical Society

|