|

President Zachary Taylor

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

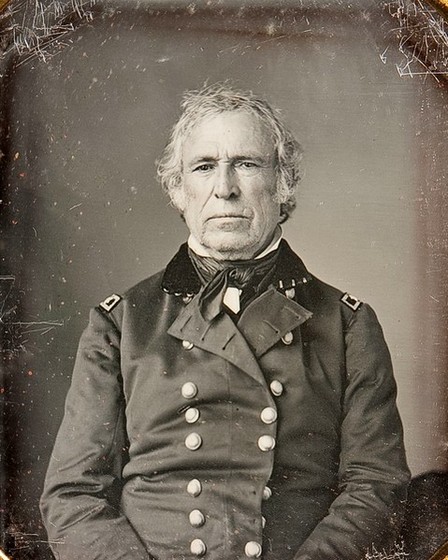

| President Zachary Taylor, ca. 1844. |

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

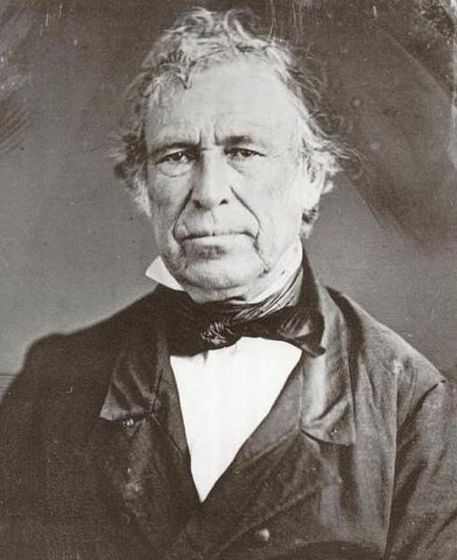

| President Zachary Taylor, ca. 1850. |

President Zachary Taylor History

Summary

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was the 12th President

of the United States, serving from March 1849 until his death in July 1850. Before his presidency, Taylor was a career officer

in the United States Army, rising to the rank of major general. His status as a national hero as a result of his victories

in the Mexican-American War won him election to the White House despite his vague political beliefs. His top priority as president

was preserving the Union, but he died sixteen months into his term, before making any progress on the status of slavery, which

had been inflaming tensions in Congress. Taylor was born to a prominent family of planters who migrated westward from Virginia

to Kentucky in his youth. He was commissioned as an officer in the U.S. Army in 1808 and made a name for himself as a captain

in the War of 1812. He rose through the ranks establishing military forts along the Mississippi River and entered the Black

Hawk War as a colonel in 1832. His success in the Second Seminole War attracted national attention and earned him the nickname

"Old Rough and Ready".

In 1845, as the annexation of Texas was underway, President James K. Polk

dispatched Taylor to the Rio Grande area in anticipation of a potential battle with Mexico over the disputed Texas–Mexico

border. The Mexican–American War broke out in May 1846, and Taylor led American troops to victory in a series of battles

culminating in the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Monterrey. He became a national hero, and political clubs sprung

up to draw him into the upcoming 1848 presidential election.

The Whig Party convinced the reluctant Taylor to lead their ticket, despite

his unclear platform and lack of interest in politics. He won the election alongside U.S. Representative Millard Fillmore

of New York, defeating Democratic candidate Lewis Cass. As president, Taylor kept his distance from Congress and his cabinet,

even as partisan tensions threatened to divide the Union. Debate over the slave status of the large territories claimed in

the war led to threats of secession from Southerners. Despite being a Southerner and a slaveholder himself, Taylor did not

push for the expansion of slavery. To avoid the question, he urged settlers in New Mexico and California to bypass the territorial

stage and draft constitutions for statehood, setting the stage for the Compromise of 1850. Taylor died suddenly of a stomach-related

illness in July 1850, ensuring he would have little impact on the sectional divide that led to civil war a decade later.

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

| Official White House portrait of Zachary Taylor. Washington. |

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

| President Zachary Taylor, 1849 |

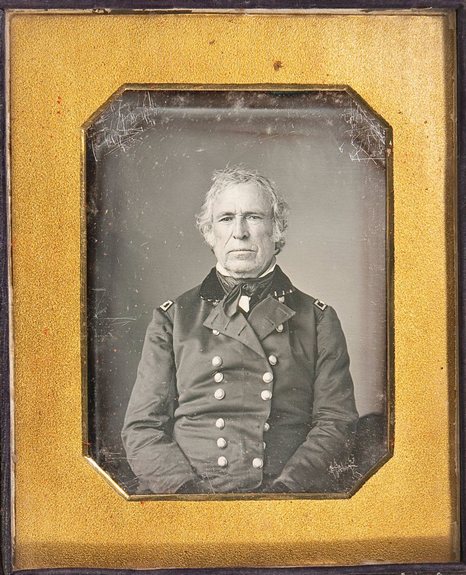

(Left) Daguerreotype of Gen. Zachary Taylor, taken at the White House, by

photographer Mathew Brady, in March 1849. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University. (Right)

Official White House portrait of Zachary Taylor. Zachary Taylor by Joseph Henry Bush, December 31, 1847.

Early Years

Taylor was born near Barboursville in Orange County, Virginia, on November

24, 1784. His father was Lieutenant Colonel Richard Taylor, a veteran of the Revolutionary War and a member of a long-established

Virginia family. Through his father, Zachary Taylor was related to President James Madison and General Robert E. Lee.

In the spring of 1785, when Zachary was only a few months old, Richard Taylor

took his family west to Kentucky (then a part of Virginia) to settle on lands he had received for his service in the Revolution.

His new plantation was along the banks of the Muddy Fork of Beargrass Creek, a few miles east of the village of Louisville.

Here Zachary Taylor spent his boyhood. At first the population of this wilderness region was small. But gradually the frontier

was pushed back, and life for the Taylors became more comfortable. The family grew to include six sons and three daughters.

Zachary probably had little, if any, formal education beyond that received at a small school in Louisville. Additional instruction

was likely given by him by his parents.

Zachary Taylor remained at home, assisting in the operation of the plantation,

until 1808. In that year he was appointed first lieutenant in the 7th Infantry Regiment. The appointment marked the beginning

of a military career that, except for one brief period, continued until Taylor's election as president 40 years later.

Early Military Career

Between 1808 and 1837, Taylor was stationed at various army posts, mostly

on the Northwest frontier but occasionally in the Southwest. During the War of 1812 (1812-14), he took part in a number of

military campaigns against the British and their Indian allies. He slowly advanced in rank, receiving his commission as major

in 1815. Later that year, when the Army was reduced to peacetime strength, he resigned rather than return to the rank of captain.

But after less than a year in civilian life, which he spent growing corn and tobacco near Louisville, Taylor was appointed

major in the 3rd Regiment. In 1819 he was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

By 1832, Taylor, now 47 years old, was a colonel, commanding the 1st Regiment.

The Black Hawk War broke out the same year, and Taylor took part in the hard-fought campaign against Chief Black Hawk and

the Sac Indians in Illinois.

Family and Home Life

This same period of nearly 30 year was important in Taylor's family and domestic

life. In 1810, he married Margaret Mackall Smith, daughter of a Maryland planter. Five daughters and one son were born to

them. Two of the daughters died in early childhood. A third, Sarah Knox, died only a few months after her marriage to Jefferson

Davis, then a lieutenant in Taylor's regiment and later to become the president of the Confederacy. The other two daughters

also married army officers. Taylor's youngest child and only son, Richard, became a lieutenant general in the Confederate

Army.

In addition to his military career, Taylor took an active interest in planting.

In 1823 he purchased a 155-hectare (380-acre) cotton plantation in northern Louisiana. In later years he bought Cypress Grove,

a much larger plantation in Mississippi.

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

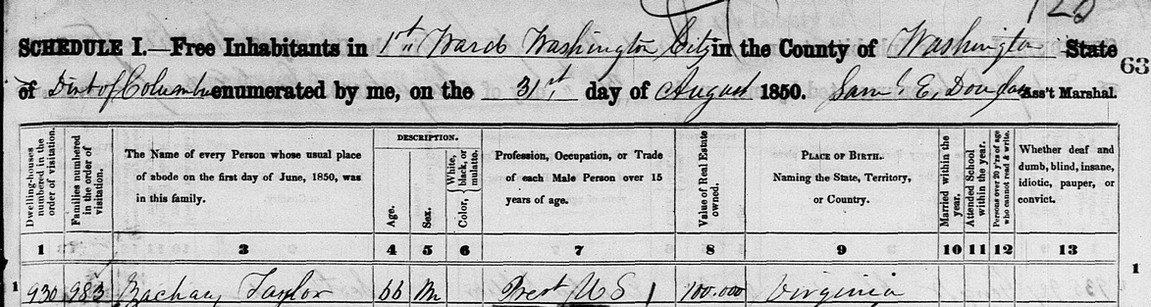

| 1850 Census Zachary Taylor |

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

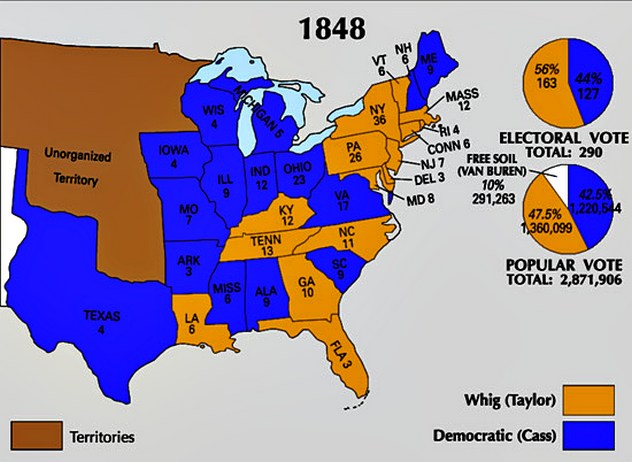

| Zachary Taylor election results |

Second Seminole War

In the summer of 1837, Taylor was ordered to take his regiment to Florida.

Since late 1835 the Army had been fighting the Seminole Indians, and reinforcements were needed. This was the start of events

that were to make Taylor a national hero and carry him to the White House.

In December 1837, with a force of nearly 1,100 men, including regular soldiers,

volunteers, and some Shawnee and Delaware Indians, Taylor set out in search of the Seminole. On December 25, after hard marching

through very rough and difficult country, he found the Seminole at Lake Okeechobee and defeated them in a desperate battle.

This victory won for Taylor the thanks of President Van Buren and a brevet (honorary) commission as brigadier general. But

the war continued, and in 1838 Taylor was placed in command. For 2 years, he directed the fighting against the Seminole. His

efforts were commended by the secretary of war, but he had no greater success in subduing the Seminole than had his predecessors.

In 1840, at his own request, he was relieved of command and assigned to duty in the Southwest. Here his main concern once

again was with the Indians.

In 1836, after winning its independence from Mexico, Texas had established

itself as an independent republic: Republic of Texas. Early negotiations for Texas to join the United States had failed, but in 1844 these negotiations were renewed. Mexico,

however, strongly opposed American annexation of Texas, and the Texans, fearing attack, requested protection from the United

States.

Taylor was ordered to Fort Jesup, close to the Texas-Louisiana border. He

remained there until July 1845, when he was ordered to move his forces to the coast of Texas. Early in 1846 he was ordered

to advance to the Rio Grande, the river that Texas claimed as its border with Mexico. On April 25, 1846, Mexican troops crossed

the Rio Grande and attacked a U.S. detachment. In May a larger Mexican force crossed the river. Although badly outnumbered,

Taylor gave battle, defeating the Mexicans at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma.

The American people hailed Taylor as a hero. Promoted to major general, he

became the second ranking officer in the U.S. Army. He was outranked only by Major General Winfield Scott, the Commanding General of the Army.

After Congress declared war on May 13, 1846, Taylor crossed the Rio Grande.

On September 25, he captured the Mexican city of Monterrey. By November 1846, he had advanced some 200 miles (320 kilometers)

into Mexico.

Meanwhile, President James K. Polk had given General Winfield Scott command

of a new Mexican expedition, and most of Taylor's best troops were transferred to Scott's forces. The angry Taylor claimed

that Polk had acted so for political reasons. (Both Polk and Scott were Democrats.) Despite orders to remain on the defensive,

Taylor advanced with his weakened forces. On February 22-23, 1847, at the battle of Buena Vista, he defeated a Mexican army

under General Antonio López de Santa Anna that was four times larger than his own. This was Taylor's last battle of the war.

Presidency

Although Taylor had no political experience, leaders of the Whig Party urged

his nomination for the presidency in 1848; Taylor at first refused but later accepted the nomination. In the election Taylor

carried eight southern and seven northern states, exactly half of the total. But he won 163 electoral votes, 36 more than

Lewis Cass, the Democratic candidate. Martin Van Buren, a former president, ran unsuccessfully as the Free Soil Party candidate.

Slavery Crisis

When Taylor was inaugurated in 1849, the nation faced a crisis.

Controversy between North and South over the question of slavery in the Western territories

had grown increasingly bitter. Opponents of slavery insisted that Congress had the constitutional authority to keep slavery out of the territories. Southerners were equally certain that Congress had no such authority,

and Southern extremists threatened secession (to leave the Union) if Congress took such action. Compromise proposals to settle

this and other slavery problems were introduced into Congress by Henry Clay. Taylor opposed them. This was partly because

he had already suggested a plan of his own, partly because of a growing feud with Clay, and partly because he believed that

the Union could not be preserved by compromise reached in the face of threats of secession.

Though a Southerner and slaveholder, Taylor had no sympathy with the southern

position in this crisis. He was ready to take the field and lead the Army himself if rebellion occurred. The measures known

as the Compromise of 1850 were not enacted until after Taylor's death, and his death was one of the factors that made their passage possible.

In the field of foreign affairs the chief accomplishment of the Taylor administration

was the negotiation of the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty with Great Britain in 1850. The treaty provided that neither country would

have exclusive control over any ship canal through Central America or could fortify such a canal. Trouble with Spain over

Cuba threatened but was avoided, and honest friendship with all nations was maintained.

| Zachary Taylor |

|

| President Zachary Taylor, 1849 |

| President Zachary Taylor |

|

| Zachary Taylor Mausoleum |

(Left) Zachary Taylor's current grave in Zachary Taylor National Cemetery

in Louisville, Kentucky. (Right) Zachary Taylor at the White House daguerreotype by Mathew Brady, 1849. Courtesy of the Beinecke

Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Taylor's Death

In his hard-fought campaigns against the Seminole, Taylor

had won the nickname of "Old Rough and Ready." But by the time he entered the White House he was no longer in robust health.

On July 4, 1850, he took part in Independence Day celebrations. After dinner that evening, he collapsed with what appeared

to be a stomach ailment but was actually cholera. He died on July 9, 1850, and was succeeded as president by Millard Fillmore.

(Rumors that Taylor might have been poisoned were disproved when his body was exhumed and tested by scientists in 1991.)

Taylor was of medium height, short-legged, and heavy-set. He dressed plainly,

at times carelessly, and made an undistinguished appearance. He was a man of absolute honesty, straightforward and simple

in manner, strong-minded and firm almost to the point of obstinacy. He was not a military genius, but he was a hard-working,

successful officer. He was not a great statesman, but he was a faithful servant of the people.

Legacy

Before he became president of the United States in 1849, Zachary Taylor served

his country for nearly 40 years as an army officer. He fought with courage and honor in the War of 1812, the Black Hawk War,

the Second Seminole War, and the Mexican War. At the close of the Mexican War he was the second highest officer in the United

States Army. His term as president was cut short by death before much had been accomplished, but not before Taylor had made

clear his devotion to the preservation of the Union, his absolute integrity, his unyielding firmness, and his modesty.

Brainerd Dyer

Author, Zachary Taylor

Content provided by the New Book of Knowledge, Copyright © 2006 Scholastic Library Publishing

Recommended Reading: Zachary Taylor:

The 12th President, 1849-1850 (The American Presidents) (Hardcover). Description: The rough-hewn general who rose to the nation’s highest office, and whose presidency

witnessed the first political skirmishes that would lead to the Civil War. Zachary Taylor was a soldier’s soldier, a

man who lived up to his nickname, “Old Rough and Ready.” Having risen through the ranks of the U.S. Army, he achieved

his greatest success in the Mexican War, propelling him to the nation’s highest office in the election of 1848. He was

the first man to have been elected president without having held a lower political office. John S. D. Eisenhower, the

son of another soldier-president, shows how Taylor rose to

the presidency, where he confronted the most contentious political issue of his age: slavery. Continued below...

The political storm

reached a crescendo in 1849, when California, newly populated after the Gold Rush, applied for statehood with an anti-slavery constitution,

an event that upset the delicate balance of slave and free states

and pushed both sides to the brink. As the acrimonious debate intensified, Taylor stood his

ground in favor of California’s admission—despite

being a slaveholder himself—but in July 1850 he unexpectedly took ill, and within a week he was dead. His truncated

presidency had exposed the fateful rift that would soon tear the country apart.

Related Reading:

Recommended Reading:

Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. Description: Zachary

Taylor was one of the most unlikely men to ever serve as president of the United

States. Self-educated, an average and conservative military leader, considered by many to

be less than intellectual, but General Zachary Taylor, affectionately referred to as the soldier’s soldier, was thrust into the limelight because of his success in the Mexican War. Although a southerner, Taylor

opposed the extension of slavery and threatened dire consequences to secessionists. (Ironically, his son, Richard Taylor,

became one of the South’s greatest Civil War generals.) Continued below...

He died unexpectedly

after serving only sixteen months as president. His death occurred just as he was reorganizing his administration and attempting

a recasting of the Whig Party. Mr. Bauer does a good job of describing the effect that Zachary Taylor had on the nation as

well as that “personal side” of the soldier’s soldier.

Recommended

Reading: Letters Of Zachary Taylor From The Battlefields Of The Mexican War (1908). Review: If you are interested in this influential episode of US

history, this book conveys it straight from the proverbial horse’s mouth. In contrast with often one-sided accounts

like President Polk's and others’ memoirs, this book displays the human side of the invasion of Mexico.

General Taylor reveals that he was conflicted in many standpoints ranging from ethical to military and political. Although

he understood that it was his duty to serve his country and fight in a war against the weaker neighbor, Mexico, he shows us an emotional and personal

side rarely seen in America’s

top brass.

Recommended

Reading: President Zachary Taylor: The Hero President (First Men, America's Presidents) (Hardcover).

Description: Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 - July 9, 1850) was an American military leader and the twelfth President of

the United States.

Taylor had a 40-year military career in the U.S. Army, serving

in the War of 1812, Black Hawk War, and Second Seminole War before achieving fame while leading U.S.

troops to victory at several critical battles of the Mexican-American War. Continued below…

Taylor's short Presidency was shadowed by the issue then dominating all aspects of American national affairs

- that of slavery. However, the immediate issue was the admission of New Mexico and California

as states. Taylor

confounded his Southern supporters, who had assumed that since the President owned slaves, he would support the pro-slavery

position and refuse entry into the union to two states settled by Northerners and likely to be anti-slavery. Taylor recommended that the

two territories develop their own constitutions and then request admission based on those constitutions. When Southern states

threatened secession he warned them that he would use all his resources as commander-in- chief to preserve the union. He stated

that if they seceded he would track them down like he had the Mexicans, and handle them in the same manner that he had deserters.

Taylor's

brief term in the White House also featured the still on-going question of balancing power between the Congress and the presidency.

Recommended

Reading: American Creation: Triumphs and Tragedies at the Founding of the Republic (Hardcover). Review: From the prizewinning author

of the best-selling Founding Brothers and American

Sphinx, a masterly and highly ironic examination of the founding years of our country. The last quarter of the

eighteenth century remains the most politically creative era in American history, when a dedicated and determined group of

men undertook a bold experiment in political ideals. It was a time of triumphs; yet, as Joseph J. Ellis makes clear, it was

also a time of tragedies—all of which contributed to the shaping of our burgeoning nation. Continued below...

From the first

shots fired at Lexington to the signing of the Declaration of Independence to the negotiations for the Louisiana Purchase,

Ellis guides us through the decisive issues of the nation’s founding, and illuminates the emerging philosophies, shifting

alliances, and personal and political foibles of our now iconic leaders—Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, and

Adams. He casts an incisive eye on the founders’ achievements, arguing that the American Revolution was, paradoxically,

an evolution—and that part of what made it so extraordinary was the gradual pace at which it occurred. He shows us why

the fact that it was brought about by a group, rather than by a single individual, distinguished it from the bloodier revolutions

of other countries, and ultimately played a key role in determining its success. He explains how the idea of a strong federal

government, championed by Washington, was eventually embraced by the American people, the majority of whom had to be won over,

as they feared an absolute power reminiscent of the British Empire. And he details the emergence of the two-party system—then

a political novelty—which today stands as the founders’ most enduring legacy. But Ellis is equally incisive about

their failures, and he makes clear how their inability to abolish slavery and to reach a just settlement with the Native Americans

has played an equally important role in shaping our national character. He demonstrates how these misjudgments, now so abundantly

evident, were not necessarily inevitable. We learn of the negotiations between Henry Knox and Alexander McGillivray, the most

talented Indian statesman of his time, which began in good faith and ended in disaster. And we come to understand how a political

solution to slavery required the kind of robust federal power that the Jeffersonians viewed as a betrayal of their most deeply

held principles. With eloquence and insight, Ellis strips the mythic veneer of the revolutionary generation to reveal men

both human and inspired, possessed of both brilliance and blindness. American Creation is a book that delineates an era of

flawed greatness, at a time when understanding our origins is more important than ever. About the Author: Joseph J. Ellis received the Pulitzer

Prize for Founding Brothers and the National Book

Award for his portrait of Thomas Jefferson, American Sphinx. He is the Ford Foundation Professor of History at Mount

Holyoke College. He lives in

Amherst, Massachusetts, with

his wife, Ellen, and their youngest son, Alex.

|