|

Creation

Of The Confederate Navy

Confederate

States Navy History

AS the different States seceded from the Union, each sovereignty made efforts to

provide for a navy, and conferred rank upon its officers. A few revenue cutters and merchant steamers were seized and converted

into men-of.war. Thus, at the beginning, each State had its own navy. At Charleston several

naval officers assisted in the capture of Fort Sumter; notably, Capt. H. J. Hartstene, in command of a picket boat, and Lieut. J. R.

Hamilton, in command of a floating battery. General Beauregard mentioned the assistance rendered by these officers; also the

services of Dr. A. C. Lynch, late of the United States

navy. Mention is also made of Lieut. W. G. Dozier, and the armed steamers Gordon, Lady Davis and General Clinch. The keels

of two fine ironclads, the Palmetto State

and the Chicora, were laid, and Commodore Duncan N. Ingraham was put in command of the naval forces.

Upon the secession of Virginia, April 17,

1861, a convention was entered into between that State and the Confederate States of America, after which the seat of the

Confederate government was removed to Richmond, and the Congress

assembled there July 20th; from which time properly commences the history of the Confederate navy. The navy department was

organized with Stephen R. Mallory, secretary of the navy: Commodore Samuel Barron, chief of the bureau of orders and detail;

Commander George Minor, chief of ordnance and hydrography; Paymaster John DeBree, chief of provisions and clothing; Surg.

W. A. W. Spottswood, bureau of medicine and surgery; Edward M. Tidball, chief clerk. The Confederate government conferred

commissions and warrants upon officers in accordance with their relative rank in the United States navy, and a more regular and satisfactory course of administration

was entered upon.

By act of Congress, April 21, 1862, the navy was to consist of 4 admirals,

10 captains, 31 commanders, 100 first lieutenants, 25 second lieutenants, 20 masters in line of promotion, 12 paymasters,

40 assistant paymasters, 22 surgeons, 15 passed assistant surgeons, 30 assistant surgeons, 1 engineer-in-chief, and 12 engineers.

But the Confederate navy register attached (see Appendix) gives the personnel of the navy on January 1, 1864.

Commodore Lawrence Rousseau was put in command of the naval forces at New

Orleans; Commodore Josiah Tattnall, at Savannah; Commodore French Forrest, at Norfolk; Commodore Duncan N. Ingraham, at Charleston,

and Capt. Victor Randolph, at Mobile. Commodores Rousseau, Forrest and Tattnall were veterans of the war of 1812, and the

last two had served with much distinction in the war with Mexico.

The name of Tattnall is a household word among all English-speaking people on account of his chivalry in Eastern waters while

commanding the East India squadron. Commodore Forrest, who had in 1856-58 commanded the Brazil squadron, threw up his commission when his native State (Virginia), seceded, and joined the South with the enthusiasm of a boy. His reward was small.

The secretary of the navy, Mr. Mallory, immediately turned his attention

to the building of a navy. He entered into innumerable contracts, and gunboats were built on the Pamunkey, York,

Tombigbee, Pedee and other rivers; but as these boats were mostly burned before completion,

it is not necessary to enumerate them. The want of proper boilers and engines would have rendered them very inefficient at

best.

The amount of work done was marvelous. "Before the war but seven steam war

vessels had been built in the States forming the Confederacy, and the engines of only two of these had been contracted for

in these States. All the labor or materials requisite to complete and equip a war vessel could not be commanded at any one

point of the Confederacy." This was the report of a committee appointed by Congress, August 27, 1862. This committee further

found that the navy department "had erected a powder-mill which supplies all the powder required by our navy; two engine,

boiler and machine shops, and five ordnance workshops. It has established eighteen yards for building war vessels, and a rope-walk,

making all cordage from a rope-yarn to a 9-inch cable, and capable of turning out 8,000 yards per month .... Of vessels not

ironclad and converted to war vessels, there were 44. The department has built and completed as war vessels, 12; partially

constructed and destroyed to save from the enemy, 10; now under construction, 9; ironclad vessels now in commission, 12; completed

and destroyed or lost by capture, 4; in progress of construction and in various stages of forwardness, 23." It had also one

ironclad floating battery, presented to the Confederate States by the ladies of Georgia,

and one ironclad ram turned over by the State of Alabama.

The navy had afloat in November, 1861, the Sumter,

the McRae, the Patrick Henry, the Jamestown, the Resolute, the Calhoun, the Ivy, the Lady Davis,

the Jackson, the Tuscarora, the Virginia, the Manassas,

and some twenty privateers. There were still others, of which a correct list cannot be given on account of the loss of official

documents. It will be remembered that on the sounds of North Carolina alone, we had the Seabird,

the Curlew, the Ellis, the Beaufort, the Appomattox, the Raleigh,

the Fanny and the Forrest. At Savannah were the Savannah, the

Sampson, the Lady Davis and the Huntress; at New Orleans,

the Bienville and others.

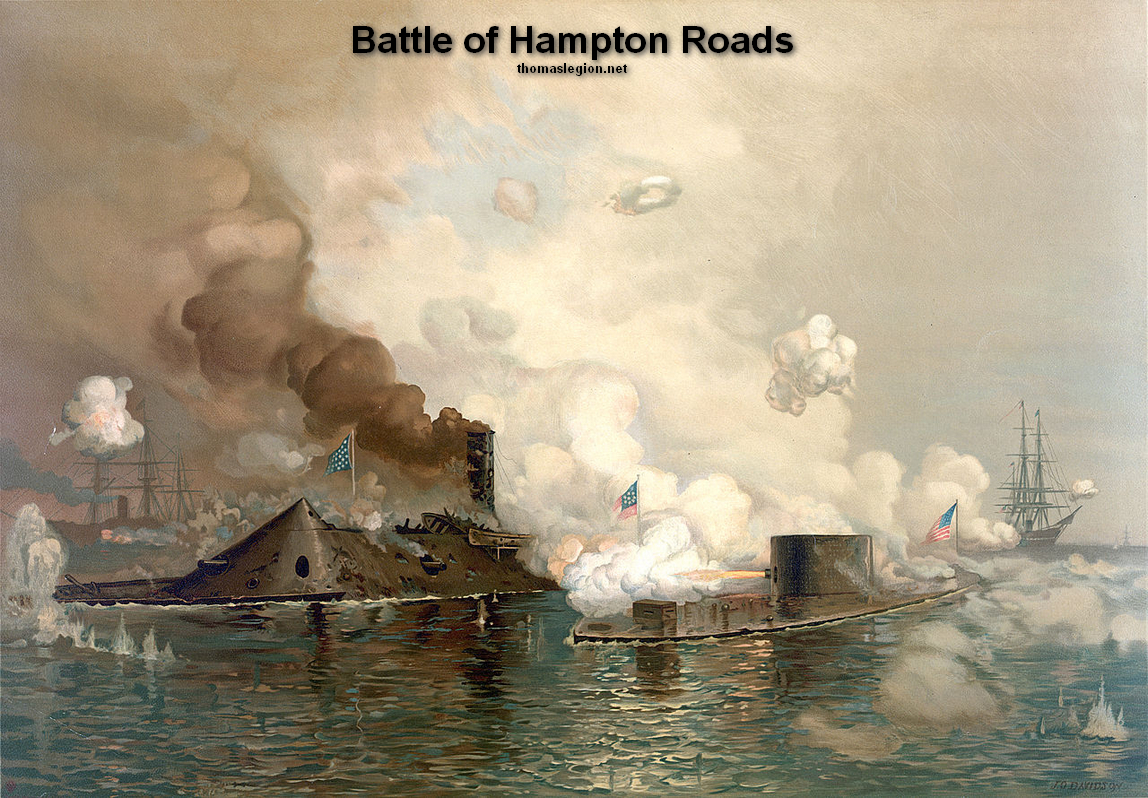

| Battle of Hampton Roads |

|

| The Battle of the Ironclads Monitor and Virginia (aka Merrimack or Merrimac) |

Upon the secession of Virginia, followed in May by Tennessee, Arkansas

and North Carolina, officers who had resigned from the United States navy were reporting in large numbers at the navy department,

but as there were no ships ready for them, they were sent to the different batteries on the York, James, Potomac and Rappahannock

rivers in Virginia, and to many other batteries on the Mississippi and other rivers. As a rule, officers were at first detailed

to do service in the States that claimed them. In Virginia we find, at Aquia creek, Commodore Lynch, Captain

Thorburn, and Lieuts. John Wilkinson and Charles C. Simms; on the Rappahannock, Lieut. H. H. Lewis; on the Potomac,

Commanders Frederick Chatard and Hartstene, and Lieuts. William L. Maury and C. W. Read; on the James, Commodore Hol-lins,

Commanders Cocke and R. L. Page, and Lieutenants Pegram, Harrison and Catesby Jones; at Sewell's point and batteries near

Norfolk, Capt. Arthur Sinclair, Commanders Mcintosh and Pinkney, Lieuts. Robert Carter and Pembroke Jones; on the York, Commanders T. J. Page and W. C. Whittle, and Lieut. William Whittle.

Lieut. Charles M. Fauntleroy was sent with two medium 32-pounders to Harper's Ferry. As the guns at these batteries were necessarily

manned by soldiers, these officers occupied rather doubtful positions, and in many cases were mere drillmasters.

In reference to the relative rank of navy and army officers, General Lee

addressed the following order to the officers at Gloucester Point for the regulation of all mixed commands:

As there are no sailors in the service, it is impossible to serve river

batteries by them, and artillery companies must perform this duty. Naval officers from their experience and familiarity with

the peculiar duties connected with naval batteries, their management, construction, etc., are eminently fitted for the command

of such batteries, and are most appropriately placed in command of them. In a war such as this, unanimity and hearty cooperation

should be the rule. Petty jealousies about slight shades of relative command and bickering about trivial matters are entirely

out of place and highly improper, and when carried so far as to interfere with the effectiveness of a command, become both

criminal and contemptible. Within the ordinary limits of a letter it is impossible to provide for every contingency that may

arise in a command which is not centered in a single individual. It is therefore hoped that mutual concessions will be made,

and that the good of the service will be the only aim of all.

In some cases, army rank was conferred upon naval officers in command of

batteries; but in this anomalous state of affairs, jealousies were constantly arising, and the navy men were only too glad

to be assigned to duty afloat.

At the navy department the work of preparing for the manufacture of ordnance,

powder and naval supplies was very heavy, and most diligently pursued. Lieut. Robert D. Minor was conspicuous in this duty,

as was also Commander John M. Brooke, whose banded guns proved so efficient. Indeed, all the navy officers were most enthusiastic

in turning their hands to any work to help the cause. Commodore M. F. Maury, who had been a member of the governor's advisory

board, organized the naval submarine battery service. Upon his departure for England

he turned it over to Lieut. Hunter Davidson, an energetic, gallant officer, who, by his skillful management of torpedoes in

the James river, contributed largely to the defense of Richmond.

Engineer Alphonse Jackson established a powder-mill; Commander John M. Brooke devised a machine for making percussion caps;

Lieut. D. P. McCorkle manufactured at Atlanta gun carriages, etc.; later in the war, Commander Catesby Jones established a

foundry for casting heavy guns, at Selma, Ala., and Chief Engineer H. A. Ramsay had charge of an establishment at Charlotte,

N.C., for heavy forging and making gun carriages and naval equipments of all kinds.

On May 31 and June 1, 1861, several vessels belonging to the Potomac

flotilla, under Commander Ward, U.S.N., cannonaded the battery at Aquia creek, under Commodore W. F. Lynch, but with no particular

result. The object of the enemy, probably, was to develop the Confederate defenses. Commodore Lynch mentioned favorably Commanders

R. D. Thorburn and J w. Cooke and Lieut. C. C. Simms. On June 27th, Commander Ward was killed on board his vessel, the Freeborn,

off Mathias point on the Potomac river. Lieutenant Chaplin, U.S.N., landed with a handful

of sailors and attempted to throw up a breastwork. He was soon driven back, but he exhibited extraordinary courage in taking

on his back one of his men who could not swim, and swimming to his boat. Batteries were at once constructed by the Confederates

at Mathias point and Evansport, and put under the charge of Commander Frederick Chatard. As the river at Mathias point is

but one mile and a half wide, the battery almost blockaded the Potomac river, and considerably annoyed, successively, the

United States steamers Pocahontas, Seminole and Pensacola. Commander Chatard was assisted by Commander H. J. Hartstene and Lieut. C. W. Read,

and others whose names are unobtainable. The

batteries on the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers were evacuated when the army retired from Manassas;

those on the York when the army fell back on Richmond, and those

on the Elizabeth when the Confederates evacuated Norfolk.

The steamer St. Nicholas, plying between Baltimore and Washington, having

been taken possession of by Commodore Hollins and Col. Richard Thomas, June 29, 1861, was taken to Coan river, and there boarded

by Lieutenants Lewis, Simms and Minor, and fifteen sailors from the Confederate steamer Patrick Henry. Hollins went first

in search of the U.S.S. Pawnee, hoping to take her by surprise. Foiled in this, he cruised in Chesapeake bay, and captured

the schooner Margaret, the brig Monticello and the schooner Mary Pierce, which prizes he

carried to Fredericksburg. Soon after this exploit Commodore

Hollins was ordered to command the naval forces at New Orleans.

Source: The Confederate Military

History, Volume 12

Recommended

Reading: A History of the Confederate Navy

(Hardcover). From Publishers Weekly: One of the most prominent European scholars of the Civil War weighs in with a provocative

revisionist study of the Confederacy's naval policies. For 27 years, University of Genoa history professor Luraghi (The Rise

and Fall of the Plantation South) explored archival and monographic sources on both sides of the Atlantic to develop a convincing

argument that the deadliest maritime threat to the South was not, as commonly thought, the Union's blockade but the North's

amphibious and river operations. Confederate Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory, the author shows, thus focused on protecting

the Confederacy's inland waterways and controlling the harbors vital for military imports. Continued below…

As a result,

from Vicksburg

to Savannah to Richmond, major

Confederate ports ultimately were captured from the land and not from the sea, despite the North's overwhelming naval strength.

Luraghi highlights the South's ingenuity in inventing and employing new technologies: the ironclad, the submarine, the torpedo.

He establishes, however, that these innovations were the brainchildren of only a few men, whose work, although brilliant,

couldn't match the resources and might of a major industrial power like the Union. Nor did

the Confederate Navy, weakened through Mallory's administrative inefficiency, compensate with an effective command system.

Enhanced by a translation that retains the verve of the original, Luraghi's study is a notable addition to Civil War maritime

history. Includes numerous photos.

Recommended

Reading: Naval Strategies of the Civil War: Confederate Innovations and Federal Opportunism. Description: One of the most overlooked aspects of the American Civil War is the

naval strategy played out by the U.S. Navy and the fledgling Confederate Navy, which may make this the first book to compare

and contrast the strategic concepts of the Southern Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory against his Northern counterpart,

Gideon Welles. Both men had to accomplish much and were given great latitude in achieving their goals. Mallory's vision of

seapower emphasized technological innovation and individual competence as he sought to match quality against the Union Navy's

(quantity) numerical superiority. Welles had to deal with more bureaucratic structure and to some degree a national strategy

dictated by the White House. Continued below...

The naval blockade

of the South was one of his first tasks - for which he had but few ships available - and although he followed the national

strategy, he did not limit himself to it when opportunities arose. Mallory's dedication to ironclads is well known, but he

also defined the roles of commerce raiders, submarines, and naval mines. Welles's contributions to the Union effort were rooted

in his organizational skills and his willingness to cooperate with the other military departments of his government. This

led to successes through combined army and naval units in several campaigns on and around the Mississippi River.

Recommended

Reading: Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War (Studies in Maritime History Series). From Library Journal: From the profusion of books

about Confederate blockade running, this one will stand out for a long time as the most complete and exhaustively researched.

Though not unaware of the romantic aspects of his subject, Wise sets out to provide a detailed study, giving particular attention

to the blockade runners' effects on the Confederate war effort. It was, he finds, tapping hitherto unused sources, absolutely

essential, affording the South a virtual lifeline of military necessities until the war's last days. This book covers it all:

from cargoes to ship outfitting, from individuals and companies to financing at both ends. An indispensable addition to Civil

War literature.

Recommended Reading: The Confederate Navy in Europe. Description: The Confederate Navy in Europe

is an account of the Confederate officers and officials who went on missions to Britain

and France to buy ships for the CS Navy,

and to support CSN operations on the high seas, such as commerce raiding. Spencer tells the story of how some officers rose

to the occasion (some did not) and did a lot with limited resources. The majority of the ships ordered never reached America. Shipbuilding takes time, and as the war dragged on

the European powers were persuaded by Confederate battlefield misfortunes and US

diplomatic pressure that it was most expedient to deny the sales of such innovative designs as ocean-going ironclads. Like

other out-manned and out-gunned powers, the CSA did have to resort to ingenuity and innovation.

Recommended

Reading: The Rebel Raiders: The Astonishing History of the Confederacy's Secret Navy (American Civil War). From Booklist: DeKay's modest monograph pulls together

four separate stories from the naval aspects of the American Civil War. All have been told before but never integrated as

they are here. The first story is that of James Bulloch, the Confederate agent who carefully and capably set out to have Confederate

commerce raiders built in neutral England.

The second is that of the anti-American attitudes of British politicians, far more extreme than conventional histories let

on, and U.S. Ambassador Charles Francis Adams' heroic fight against them. The third is a thoroughly readable narrative of

the raider Alabama and her capable, quirky captain, Raphael

Semmes. The final story is about the Alabama claims--suits for damages done to the U.S. merchant marine by Confederate raiders, which became

the first successful case of international arbitration. Sound and remarkably free of fury, DeKay's commendable effort nicely

expands coverage of the naval aspects of the Civil War.

|