|

|

(Left) Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was a

career U.S. Army officer, achieving the rank of major general in the Union Army during the Civil War. Although he served throughout

the war, usually with distinction, Hooker is best remembered for his crushing defeat by Robert E. Lee at the Battle of

Chancellorsville in 1863. (Right) Robert E. Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12,

1870) was a career military officer who is best known for having commanded the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the

American Civil War. Lee married Mary Custis, the great granddaughter of Martha Washington, and distinguished himself during

the Mexican-American War (1846 -- 1848).

On May 1, Hooker reverted to a rather cautious approach toward Lee.

He halted his advance, bivouacked while still inside the tangle of the Wilderness, and then ordered his men

into a defensive posture. Had he continued to press Lee in more open country, his superior numbers would have given him a

decided advantage, especially with respect to his artillery.

With Hooker paused in the Wilderness, Lee and Jackson conceived a bold but

risky plan to strike Hooker first. Lee divided his forces once again and sent Jackson's corps on a long march to turn Hooker's

unprepared right flank. Late in the afternoon of May 2, Jackson slammed into Hooker's flank, routing the XI Corps and apparently

unnerving the now entrenched Hooker. Tragically for the Confederacy, however, Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men

during the confusing aftermath of the initial assault. He would die of pneumonia only eight days later.

On May 3, Sedgwick attacked and broke through Early's defenses in an

attempt to come to the aid of Hooker, but he was checked again near Bank's Ford and Salem Church. On May 4, Lee launched

an offensive against Sedgwick, but could not drive him from his position. Meanwhile, Hooker continued contracting his own

lines and constructing defensive fortifications, but later that night, he made a reversal of action and ordered

a full retreat of the Army of the Potomac.

Although Lee had desired to press the action against Hooker's

army, he would have assailed a well-entrenched Federal command while receiving costly Confederate losses in

the engagement.

Hooker had cast his lot with Gen. Stoneman, but now, with the new cavalry

commander having failed in his attempt to penetrate behind enemy lines, "Fighting Joe" regretted his decision, insomuch that he placed the blame for the Union defeat squarely on the shoulders of Stoneman. Hooker, however, had lost his will to fight against the aggressive Lee and

Jackson. The troops of the Army of the Potomac were still full of fight, but "Fighting Joe" Hooker had had enough. He would

fire Stoneman immediately, but he too would receive the same fate by being relieved of command of the army in mid-June.

| Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia |

|

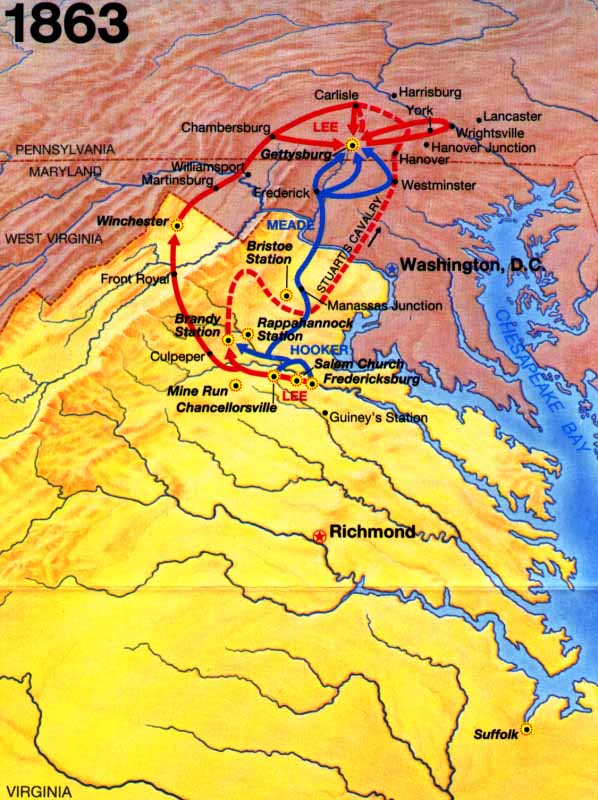

| Enhanced Map of Virginia Civil War Battles in 1863 |

| Battle of Chancellorsville Campaign Map |

|

| 1863 Virginia Civil War Battles |

Background

After the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Union high command was in turmoil.

The repeated frontal attacks on Marye's Heights that had provoked Lee to comment famously on the terribleness of war had also

caused "Fighting Joe" Hooker, in protest, to stop fighting. "I had lost as many men as my orders required me to lose," he

explained later. Such was the standing of Ambrose E. Burnside among his fellow generals. They were in near open revolt against

the bushy-cheeked West Pointer, and, remarkably, he seemed to agree with their assessment. After all, he had accepted command

of the Army of the Potomac only after refusing it twice and then insisting that he wasn't up to the job. Following the post-Fredericksburg

debacle known as the "Mud March," U.S. president Abraham Lincoln decided that he agreed, and he replaced Burnside with Hooker.

Hooker was a red-faced, big-mouthed brawler from Massachusetts with a perhaps

unfair reputation for drinking and gambling. Not a fan of his nickname, he immediately set about proving to a skeptical president

that he added up to more than outrageous boasts and headlong charges. (When Hooker had declared that what the country really

needed, and quick, was a dictator, Lincoln dared him first to win glory on the battlefield, after which "I will risk the dictatorship.")

Hooker's first step was to reshape his army into a tighter, more disciplined,

and more effective force. He rounded up the many thousands of stragglers and deserters, issued all the men tastier food, and

instituted a furlough lottery so that they could go home once in awhile. He got rid of Burnside's cumbersome "Grand Divisions"

and gave each of his corps distinctive insignia, which helped clear up certain battlefield confusions while nudging his men

toward something like an esprit de corps. Finally, he centralized his fast-improving cavalry (while, mysteriously, not doing

the same with his artillery) and put Colonel George H. Sharpe in charge of his military intelligence. For the first time in

the Potomac army's history, its commander knew exactly what lay before him.

Now, as ever, that was Robert E. Lee, whose army at the end of April 1863

numbered 61,000, putting him at a more than two-to-one disadvantage. Two additional Confederate divisions, under James Longstreet,

were away to the southeast, encircling Suffolk. The idea was to capture food and supplies for an army that was rich with military

victories but, due to logistical hang-ups, still hungry and without nearly enough shoes. Lee was well fortified behind the

Rappahannock, but, otherwise, his was not an ideal position. When the fighting started, Longstreet was still too far south

to help.

Hooker's plan was to send all but a couple brigades of cavalry, under the

command of George Stoneman, on a wide loop to the west and south and into the rear of Lee's army, cutting his supply lines.

Meanwhile, two Union corps under John Sedgwick—a force almost the size of Lee's entire army—would feint an attack

in front of Fredericksburg while the remainder of the Potomac army secretly crossed the Rapidan River and crashed into Lee's

left flank. By April 30, Stoneman had gone incommunicado, but all else was mostly according to plan. That night, three Union

corps under Henry W. Slocum camped in the Wilderness, near an old tavern called Chancellorsville, waiting to push east in

the morning.

| Civil War Battle of Chancellorsville Map |

|

| Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, Map. Courtesy army.mil |

At the Battle of Chancellorsville, General Robert E. Lee received both his

greatest victory and greatest loss. While Lee delivered a crushing defeat to Hooker, friendly fire from North Carolina troops

mortally wounded Stonewall Jackson. As Jackson lay dying, Lee sent a message through Chaplain Lacy, saying "Give General Jackson

my affectionate regards, and say to him: he has lost his left arm but I my right." The night Lee learned of Jackson's death,

he told his cook, "William, I have lost my right arm" and "I'm bleeding at the heart."

Chancellorsville

Campaign (The Battle of Chancellorsville, Second Battle of Fredericksburg) was fought May 1–6, 1863, at Chancellorsville,

Virginia, just west of Fredericksburg in the Wilderness, and at Fredericksburg. The opposing commanding generals were Union

general Joseph Hooker and Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson. Casualties during the campaign

(including Marye's Heights and Salem Church) for the Union Army were 17,304

(1,694 dead, 9,672 wounded, 5,938 missing), while the Confederacy suffered 13,460 (1,724 dead, 9,233 wounded, 2,503 missing).

As a major battle of the Civil War, Chancellorsville is also listed as one of the Ten Bloodiest and Costliest

American Civil War Battles.

The Chancellorsville Campaign, which culminated in the Battle of Chancellorsville, fought May 1–6,

1863, produced one of the most stunning and ambivalent Confederate victories of the American Civil War (1861–1865).

Confederate general Robert E. Lee had trounced the Army of the Potomac at Fredericksburg the previous December, but since

then, Joseph Hooker had thoroughly reorganized and revitalized his dispirited Union troops. Declaring that he had created

"the finest Army on the Planet," he set into motion an elaborate plan designed to quietly turn the left flank of the outnumbered

and underfed Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, which was camped not far from Fredericksburg. In the face of Hooker's

attack, Lee dangerously divided his army, sending Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson through the Wilderness, a wild and tangled

woodland, and around Hooker's right side in what became one of the most famous flanking maneuvers of the war. A combination

of bad Union generalship and good Confederate luck forced Hooker to retreat across the Rappahannock River. Jackson was accidentally

killed by his own men in the fighting, and while his death may have been devastating for the Confederacy, so were the additional

13,459 casualties. Combined with the shocking losses at Gettysburg two months later, they nearly destroyed the army's offensive

capabilities.

| Chancellorsville Battlefield Map |

|

| Civil War Chancellorsville Battlefield Map |

(About) Title "Battle of Chancellorsville". Created / Published in 1863.

Subject Headings -- Chancellorsville, Battle of, Chancellorsville, VA., 1863--Maps -- United States--Virginia--Chancellorsville

-- Chancellorsville (VA.), Battle of Notes -- Scale ca. 1:190,000. -- Library of Congress Civil War Maps (2nd

ed.), 527 -- Map 1: Dispositions of the Union and Confederate armies prior to the battle of Chancellorsville. -- Map

2: Dispositions of Union and Confederate forces about 11:30 P.M., 30 April, 1863. -- Map 3: Dispositions of Union and Confederate

forces at 4:00 P.M., 2nd May, 1863. -- Each map indicates Union and Confederate troop positions, roads, railroads, towns,

drainage, fords, and a few houses and names of inhabitants. -- Description derived from published bibliography. Maps

enhanced for clarity. Library of Congress.

Timeline

April

14, 1863- Union cavalry general George Stoneman begins to cross the Rappahannock River. His mission—what will come to

be known as Stoneman's Raid—is to make a wide loop to the west and south and into the rear of Robert E. Lee's Confederate

army, cutting its supply lines.

April 15, 1863- Bad weather forces Union cavalry general George Stoneman

to retreat north across the Rappahannock River.

April 27–29, 1863- After two weeks of bad weather and delays,

Union cavalry general George Stoneman finally leads his troopers across the Rappahannock River on their raid behind Confederate

lines. Union commander Joseph Hooker's goal is to outflank Robert E. Lee's Confederates east of the vast Virginia scrub forest

known as the Wilderness.

April 30, 1863- The Union Fifth, Eleventh, and Twelfth corps reunite

on the south side of the Rappahannock River and march east in an attempt to outflank Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

That night, the troops camp in the Wilderness, a wild and tangled woodland, near an old tavern called Chancellorsville.

April 30, 1863- By this day, raiding cavalrymen under Union general

George Stoneman have lost touch with Union commander Joseph Hooker. Their mission is to cut Confederate supply lines.

May 1, 1863- Confederate general Robert E. Lee divides his army, leaving

a small force in Fredericksburg and marching the rest west to face advancing Union troops. The two armies clash near Chancellorsville

in a day of fierce fighting.

May 1, 1863, evening- Union commander Joseph Hooker instructs the Eleventh

Corps, on the army's far right flank, to dig in. Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson notice

the flank's weakness and make plans to attack it.

May 2, 1863, 7 a.m.–5:30 p.m.- Confederate general Robert E. Lee

divides his army a second time. He sends 29,400 men under Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson twelve miles through the dense forest

known as the Wilderness and around to the Union right flank. He leaves himself fewer than 15,000 men to face down the bulk

of the Union army.

May 2, 1863, morning- Union observers in tall trees spot the Confederate

flanking march through the Wilderness as the troops head through a clearing near Catharine Furnace. Union commander Joseph

Hooker assumes that Cavalry General George Stoneman has been successful in cutting off the Confederate supply line. He announces

that Robert E. Lee is in retreat.

May 2, 1863, Noon–5:30 p.m.- Parts of the Union Third Corps attempt

to attack Confederate troops on the march against the Union's exposed right flank. The attack, at a clearing in the Wilderness

near Catharine Furnace, is beaten back by Confederates under the personal command of Robert E. Lee.

May 2, 1863, 5:30 p.m.- Confederate troops under Thomas J. "Stonewall"

Jackson, having marched all day around the Union right flank, attack and rout the German immigrants who make up the Union

Eleventh Corps.

May 2, 1863, 9:30 p.m.- At the end of one of the bloodiest days of the

Civil War, Confederate general Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson is accidentally shot by North Carolina infantrymen. His next

in command, A. P. Hill, is also wounded. Leadership of the Confederate Second Corps is transferred to the cavalry general

J. E. B. Stuart.

May 3, 1863- J. E. B. Stuart, eventually reuniting his corps with Confederates

under the direct command of Robert E. Lee, launches a brutal frontal assault against Union forces under Joseph Hooker.

May 3, 1863, afternoon- After days of delay, the Union Sixth Corps under

John Sedgwick attacks the Confederate troops, commanded by Jubal A. Early, defending Marye's Heights near Fredericksburg.

Robert E. Lee marches a small force east to prevent Sedgwick's men from reuniting with the rest of the Union army.

May 4, 1863- The Union Sixth Corps under John Sedgwick continues to

battle Confederate troops under Jubal A. Early around Fredericksburg. The bloody fighting near Chancellorsville, meanwhile,

has finally stopped.

May 5, 1863, pre-dawn- The result of a miscommunication, the Union Sixth

Corps under John Sedgwick retreats north across the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg. Days of tough fighting, frayed

nerves, and the fear that Confederate reinforcements under James Longstreet might soon arrive contribute to Sedgwick's premature

action.

May 6, 1863- When he learns that the Sixth Corps had retreated across

the Rappahannock River the day before, Union commander Joseph Hooker realizes that the Battle of Chancellorsville is finished.

He follows Sedgwick north with the rest of his army.

May 10, 1863, 3:15 p.m.- Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson dies of pneumonia

at Fairfield, the home of Thomas and Mary Chandler, having spoken as his last recorded words: "Let us cross over the river

and rest in the shade of the trees."

| Battle of Chancellorsville |

|

| Confederate dead during Chancellorsville Campaign |

(About) Photograph of Confederate dead behind the stone wall of Marye's

Heights, Fredericksburg, Virginia, killed during the Chancellorsville Campaign in May 1863. Marye's Heights is also known

as the Second Battle of Fredericksburg, Photograph by A.J. Russell. Library of Congress.

The Campaign

Because of his superb intelligence, Hooker's knowledge of Lee's order of

battle rivaled that of historians a hundred and fifty years later, but without cavalry, he could not follow the Confederates

or even find them. His men, in the words of British historian Brian Holden Reid, "stumbled about like partygoers pushed from

a brightly lit anteroom into a deep, pitch-black cellar." When they stumbled into Stonewall Jackson's Second Corps while still

surrounded by the nearly impenetrable brambles of the Wilderness—a pitch-black cellar is right—they were startled

into falling back. By nightfall on May 1, after a fierce day of fighting, Hooker was back to where he had started at Chancellorsville.

An entire school of historians has called this first day decisive, suggesting

that Hooker was too cautious, too much in the tradition of Union general George B. McClellan. To quote Reid, "The ghost of

McClellan had materialized." Bruce Catton was harsher: "Perhaps Joe Hooker had lost his nerve." Stephen W. Sears, in contrast,

has noted that Hooker "was neither disheartened nor had he lost confidence in himself or in his plan." He had always intended

to fight defensively, to avoid those ugly headlong charges. And while Hooker busied Oliver O. Howard and his Eleventh Corps

with shoring up the end of the line, Lee and Jackson seated themselves on fallen logs and talked late into the night.

The plan they came up with was nothing short of a desperate gamble: Jackson

would march his entire corps twelve miles under cover of the Wilderness, past an old iron furnace, and around to Hooker's

vulnerable right. (Howard's men weren't actually shoring up much of anything.) Lee, who had sniffed out Sedgwick's feint from

the start, would be left with a skeleton force. The next morning, Jackson's troops were spotted by a Union reconnaissance

balloon, but Hooker was confounded by bad communication. When he finally heard of the march, he announced, with perhaps a

bit too much self-congratulation, that Lee must be retreating. In fact, Jackson's men rushed screaming out of the forest at

about five thirty in the afternoon on May 2 and set the German immigrants of Howard's Eleventh Corps to terrible flight—leaving

them forever to be disparaged as the "Flying Dutchmen."

Jackson embodied relentlessness, and with his subordinate A. P. Hill grumbling

behind him, he scouted the front for a possible night attack. That is when friendly fire struck him down, also wounding Hill.

The Second Corps transferred to the ranking general in the field, the cavalryman J. E. B. Stuart, who, without any other plan

to work from, threw his troops at Hooker the next morning. The fighting was as hot and close as any in the war—the vast

majority of the battle's casualties occurred on this day—and Hooker himself suffered a concussion when a wooden beam

from the Chancellor family house fell on him. Rumors immediately circulated that he was drunk, and historians have argued

for years about the extent to which the stalemate that followed was a symptom of Hooker's decision not to remove himself from

command. (Or was it that he lost his nerve again? A 1910 history of the battle has Hooker telling a subordinate that "I was

not hurt by a shell and I was not drunk. For once I lost confidence in Hooker, and that is all there is to it." The historian

Sears has thoroughly dismissed this account, however.)

Nevertheless, with Sedgwick waiting at Fredericksburg, the game was still

Hooker's to win. Sedgwick was an old army regular who had been wounded three times at Antietam (1862), and he did not seem

anxious to jump into this fight. Still, on May 3, he sent his Sixth Corps up Marye's Heights three times before finally overwhelming

Confederate general Jubal A. Early's outnumbered Mississippians. So much for avoiding headlong charges, even if this Second

Battle of Fredericksburg was more successful for the Army of the Potomac than the first. Lee was forced to rush reinforcements

from the Wilderness. Those men, combined with bad communication, frayed nerves, and the fear of Longstreet's men finally appearing

from the south like avenging ghosts, forced Sedgwick to retreat across the Rappahannock early in the morning on May 5. The

next day—with the battle not quite lost and the Union troops certainly not feeling whipped—Hooker followed.

| Chancellorsville Campaign |

|

| 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville Map |

Aftermath

As the battle started, Hooker had promised his army that "certain destruction

awaits" the enemy. A few days later, his generals could only shake their heads. They had lost 17,304 men, nearly as many as

at Antietam. Worse, from their perspective, was the fact that Hooker had not engaged the whole army—the entire First

Corps sat idle for much of the battle. The Confederates enjoyed no such luxury. Time and again they were forced to commit

everything they had, and everything they had usually was not enough for a complete victory. Still, a consensus has formed

that Lee's incomplete victory, accomplished in the face of overwhelming odds and with a kind of preternatural coolness, was

the most brilliant example of generalship in the war.

Of course, Lee's casualty total was devastating, too, adding up to more

than 13,000 and weakening the army's fighting ability even at a time when morale was high. The most famous of those casualties

was Stonewall Jackson. His final charge assured his place not just in history but in mythology. As Lee told the young officer

who brought him the news of his general's wounding, "Captain, any victory is dearly bought that deprives us of the services

of Jackson even temporarily." Lee would ride the momentum of Chancellorsville north to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in July,

but there, his coolness would fade. The fierce and flamboyant competence of his subordinates would falter. And Jackson's absence—his

corps was given to the eccentric and one-legged Richard S. Ewell, nicknamed "Old Bald Head"—would be blamed, rightly

or wrongly, for the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Gettysburg. (Historians disagree and the debate has traditionally

been waged within the historically suspect parameters of the Lost Cause view of the Civil War.)

Hooker, too, would be gone. His generals revolted against him just as he

had once revolted against Burnside. In his own defense, he argued that Stoneman's cavalry raid, which reached the outskirts

of the Confederate capital at Richmond and caused a good bit of panic, nevertheless failed to cut Lee's supply lines. He complained

that Howard's men had run rather than fight. (Howard, who was particularly religious, labeled Hooker "impure" and accused

him of swearing too much. That Howard would later be promoted over him was just one more insult to Fighting Joe.) Finally,

he wondered why Sedgwick had not been more aggressive at Fredericksburg. In the end, though, Lincoln demanded results and

so turned to George G. Meade. The army Meade took to Pennsylvania, however, was better equipped and better organized than

it had been before Hooker. And many of its men did not believe that they had truly been beaten at Chancellorsville. As one

Massachusetts soldier put it, "The morale of the Army of the Potomac was better in June than it had been in January."

Credits: Confederate Military History; Wolfe, Brendan. "Chancellorsville

Campaign." Encyclopedia Virginia. Ed. Brendan Wolfe. 31 Jan. 2013. Virginia Foundation

for the Humanities. 29 Nov. 2012 <http://www.EncyclopediaVirginia.org/Chancellorsville_Campaign>.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|