|

|

New York in the American Civil War

New York Civil War History

| New York in the Civil War |

|

| Province of New York (1665 - 1783) |

Introduction

New York was one of the Thirteen Colonies that rebelled against British

rule during the American Revolution and it was the location for approximately one-third of the battles. New York became the

11th state by ratifying the United States Constitution on July 26, 1788.

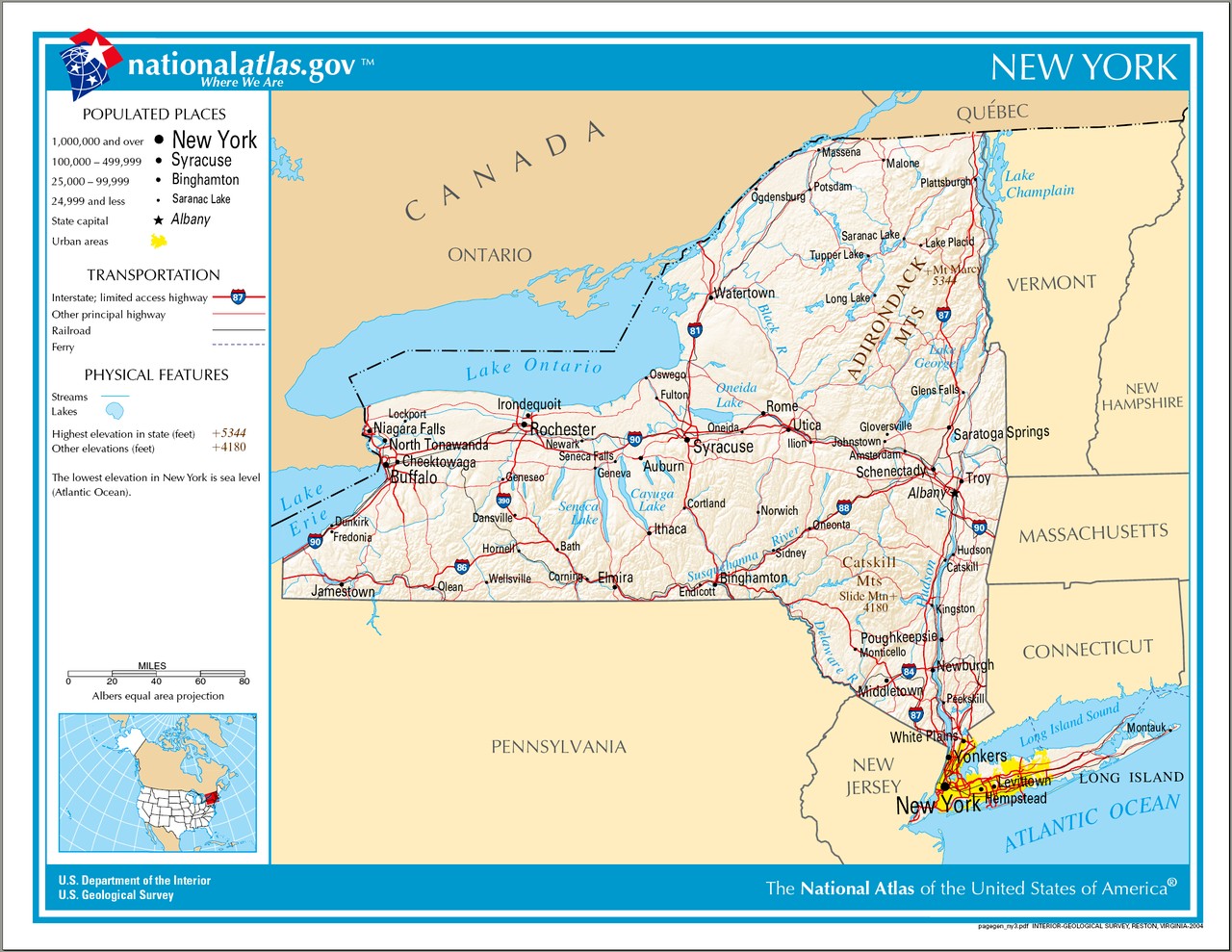

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States.

New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east.

The state has a maritime border with Rhode Island east of Long Island, as well as an international border with the Canadian

provinces of Ontario to the west and north, and Quebec to the north.

New York was inhabited by various tribes of Algonquian and Iroquoian

speaking Native American tribes at the time Dutch settlers moved into the region in the early 17th century.

New York was discovered by the French in 1524 and first claimed by the

Dutch in 1609. Fort Nassau was built near the site of the present-day capital of Albany in 1614. The Dutch soon also settled

New Amsterdam and parts of the Hudson River Valley, establishing the colony of New Netherland. In 1664, England renamed the

colony New York, after the Duke of York. New York City gained prominence in the 18th century as a major trading port in the

Thirteen Colonies. The borders of the British colony, the Province of New York, were roughly similar to those of the present-day

state. Approximately one-third of all the battles of the Revolutionary War took place in New York, and the state constitution

was enacted in 1777.

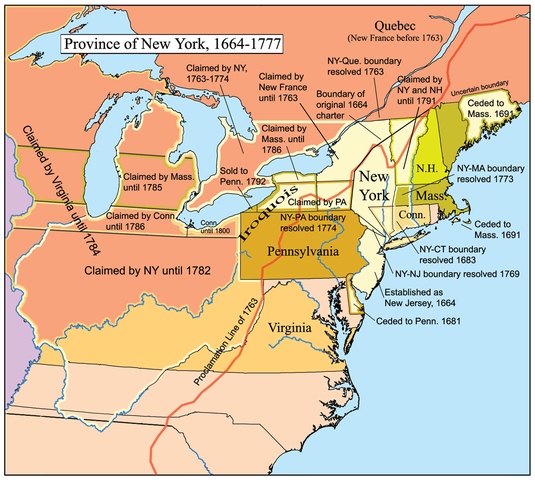

The Province of New York (1664–1783) was an English and later British

crown territory that originally included all of the present U.S. states of New York, New Jersey, Delaware and Vermont, along

with inland portions of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Maine, as well as eastern Pennsylvania. The majority of this land

was soon reassigned by the Crown, leaving territory that included the valleys of the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers, and Vermont.

The territory of western upstate New York was Iroquois land, also disputed between the English colonies and New France, and

that of Vermont was disputed with the Province of New Hampshire.

The province resulted from the surrender of

Provincie Nieuw-Nederland by the Dutch Republic to the Kingdom of England in 1664. Subsequently, the province was renamed

for James, Duke of York, brother of Charles II of England. The territory was one of the Middle Colonies, and ruled at first

directly from England.

The New York Provincial Congress of local representatives declared itself the government

on May 22, 1775, first referred to the "State of New York" in 1776, and ratified the New York State Constitution in 1777.

While the British regained New York City during the American Revolutionary War using it as its military and political base

of operations in North America, and a British governor was technically in office, much of the remainder of the former colony

was held by the Patriots. British claims on any part of New York ended with the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

In the 19th century, New York hosted significant transportation advancements

including the first steamboat line in 1807, the Erie Canal in 1825, and America's first regularly scheduled rail service in

1831. These advancements led to the expanded settlement of western New York. By 1840, New York was home to seven of the nation's

thirty largest cities.

Advancing transportation quickly led to settlement of the fertile Mohawk

and Gennessee valleys and the Niagara Frontier. Buffalo and Rochester became boomtowns. Significant migration of New England

"Yankees" (mainly of English descent) to the central and western parts of the state led to minor conflicts with the more settled

"Yorkers" (mainly of German, Dutch, and Scottish descent). More than 15% of the state's 1850 population had been born in New

England. The western part of the state grew fastest at this time.

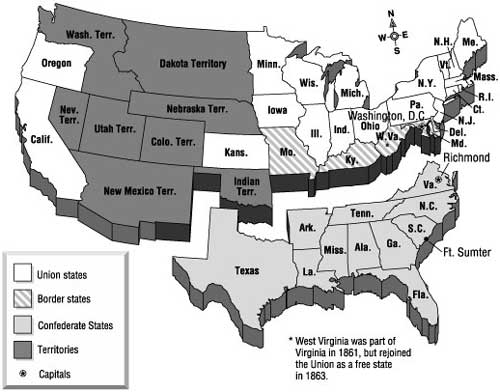

Hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers joined the Union Army during the American

Civil War (1861-1865), more than any other Northern state. A war was not in the best interest of business, because much of

New York's trade was based on moving Southern goods. New York City's large Democrat community feared the impact of Abraham

Lincoln's election in 1860. By the time of the 1861 Battle of Fort Sumter, however, political differences had vanished and

the state quickly met Lincoln's request for soldiers and supplies. While no battles were waged in New York, the state wasn't

immune to Confederate conspiracies, including one to burn various New York cities and another to invade the state via Canada

The state of New York during the Civil War was a major influence in

national politics, the Union war effort, and the media coverage of the war. New York was the most populous state in the Union

during the Civil War, and provided more troops to the Union Army than any other state, as well as several significant military

commanders and leaders. The Empire State was politically divided, with a significant peace movement, particularly in the mid-

to late-war years, as well as being a strong bastion of Radical Republicans who favored harsh treatment of the rebelling Confederate

States of America. New York provided a key member of the Lincoln Administration, as well as several important voices on Capitol

Hill.

The press and media of the state, heavily concentrated in New York City,

influenced not only state politics and the public's view on the war, but helped shape and mold national opinion as well. Important

periodicals based in New York included Harper's Weekly, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, and others. German-born illustrator

Thomas Nast was among the early political cartoonists. In the decades after the war ended, numerous memorials and monuments

were erected across the Empire State to commemorate specific regiments, units, and officers associated with the war effort.

Several archives and repositories, as well as historical societies, hold archives and collections of relics and artifacts.

| New York Civil War Map |

|

| New York Slavery Map |

Slavery

Slavery in New York began when the Dutch West India Company imported 11

African slaves to New Amsterdam in 1626, with the first slave auction being held in New Amsterdam in 1655. The British expanded

the use of slavery, and in 1703, more than 43 percent of New York households owned slaves, often as domestic servants and

laborers. Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city.

During the American Revolutionary

War, the British troops occupied New York City in 1776, and the Crown promised freedom to slaves who fled rebel masters.

By 1780, 10,000 blacks lived in New York; many were slaves who had escaped from slaveholders in North and South. After

the American Revolution, the New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785 to work for the abolition of slavery and for

aid to free blacks. The state passed a law for gradual abolition in 1799; after that date, children born to slave mothers

were free but required to work an extended indentured servitude into their twenties. All slaves were finally freed on July

4, 1827 and blacks in New York celebrated with a large parade.

New York residents, however, were less willing to give blacks equal voting rights. By the constitution

of 1777, voting was restricted to free men who could satisfy certain property requirements. This property requirement disfranchised

poor men among both blacks and whites. The reformed Constitution of 1821 conditioned suffrage for black men by maintaining

the property requirement, which most could not meet, so effectively disfranchised them. The same constitution eliminated the

property requirement for white men and expanded their franchise. No women yet had the vote in New York. "As late as 1869,

a majority of the state's voters cast ballots in favor of retaining property qualifications that kept New York's polls closed

to many blacks. African-American men did not obtain equal voting rights in New York until ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment

in 1870."

| New York in the American Civil War Map |

|

| New York and Sectionalism Map |

Sentiment

In the presidential election of 1860, 362,646 (53.7%) New Yorkers voted

for Abraham Lincoln, while 312,510 (46.3%) supported Democrat Stephen Douglas.

Powerful New York politicians played important roles in setting national

policy and procedures during the American Civil War. Roscoe Conkling was among the leading Radical Republicans who strongly

supported the vigorous prosecution of the war. They were opposed by moderate Republicans including Henry Jarvis Raymond, a

New York newspaperman who served as the Chairman of the Republican National Committee in the latter half of the war. William

H. Seward, an outspoken critic of Lincoln and a former 1860 presidential candidate, became the Secretary of State and an important

member of Lincoln's Cabinet.

By contrast, the colorful mayor of New York City, Fernando Wood, was

a prominent early supporter of the Confederate cause. He argued unsuccessfully that the city should secede from the Union

as a separate entity.

When the war began, former New York Governor Horatio Seymour (1853-54;

1863-64) took a cautious middle position within his Democratic Party, supporting the war effort but criticizing its conduct

by the Lincoln administration. Seymour was especially critical of Lincoln's wartime centralization of power and restrictions

on civil liberties, as well as his support of emancipation. In 1862, Seymour was again elected governor, defeating Republican

candidate James S. Wadsworth. As governor of the Union's largest state, Seymour was the most prominent Democratic opponent

of the President for the next two years. He strongly opposed the Lincoln administration's institution of the military draft

in 1863.

Alfred Ely, Chairman of the House Committee on Invalid Pensions, was

among the first U.S. representatives to be captured by the Confederate Army when he and other civilian onlookers were taken

prisoner following the First Battle of Bull Run. He spent six months in a Confederate prison before being exchanged and released.

In 1861 and 1862, former U.S. Senator Hamilton Fish became associated

with John A. Dix, William M. Evarts, William E. Dodge, A.T. Stewart, John Jacob Astor, and other New York men on the Union

Defence Committee. They cooperated with the New York City government in raising and equipping troops, and disbursed more than $1

million dollars for the relief of New York volunteers and their families. Later in the war, several leading New York

politicians and businessmen helped found the Union League, a pro-Union, pro-Lincoln organization that helped fund the Republican

Party, as well as charitable relief groups such as the United States Sanitary Commission.

During the Gettysburg Campaign of 1863, despite his sharp political differences with Pennsylvania's Republican Governor Andrew G. Curtin, Governor Seymour

dispatched significant quantities of New York State Militia to Harrisburg to help repel the invasion of Robert E. Lee's Army

of Northern Virginia. The first Union soldier killed on Pennsylvania soil was a native Pennsylvanian, Corporal William H.

Rihl serving in a company assigned to the 1st New York Cavalry.

During the New York draft riots, approximately 1000 were killed (including

100 blacks) and more than 2,000 were injured. The draft riots also resulted in nearly $2 million dollars in property damage.

Coupled with strong anti-war movement, by Copperheads and other Peace Democrats, it made New York one of the closest contested

states in the presidential election of 1864. 368,735 (50.46%) New Yorkers chose the incumbent Abraham Lincoln, with 361,986

(49.54%) supporting Democrat challenger and former Union general George B. McClellan. Lincoln won the Empire State by a meager

6,749 votes and captured all 33 electoral votes.

The New York Legislature oversaw the approval of funding the state's

war effort, including bounties, fees, expenses, interest on loans, and for the support of the families of soldiers. Total

expenditures exceeded $152 million during the war.

| New York in the Civil War |

|

| Total New York Civil War Units |

Civil War

According to the 1860 U.S. census, New York had a total population of 3,880,735,

including 49,005 free colored persons. The state's population had been transformed by extensive immigration from the 1840s, particularly from Ireland and Germany. Shortly before the Civil War, 25 percent of

New York City's population was born in Germany.

During the Civil War, more than 400,000 New Yorkers joined the

Union Army, and, according to Frederick Phisterer, New York in the War of the Rebellion, 1861 To 1865, Albany: Weed, Parsons

and Co. (1890), more than 53,000 New York soldiers died in service, or roughly 1 of every 7 who served. During the Civil War,

the State of New York ranked 1st (followed by Pennsylvania in 2nd, Ohio 3rd, Illinois 4th, and Indiana 5th) in

total soldiers serving in the Union military. The Union Army (1908) indicates that New York also provided more sailors

and marines to the Union military than any other Northern state. "The sons of the Empire State were to be found in every important

naval engagement throughout the war. That they paid the debt of patriotism and valor is attested by the fact that 1,880 perished

in battle, from disease and from other causes incident to the service."

For the Union military, Frederick Dyer, A Compendium of the War

of the Rebellion (1908), indicates that New York raised 409,561 soldiers, 35,164

sailors and marines, and 4,125 colored troops. Aggregate 448,850; Total Deaths All Causes 46,534.

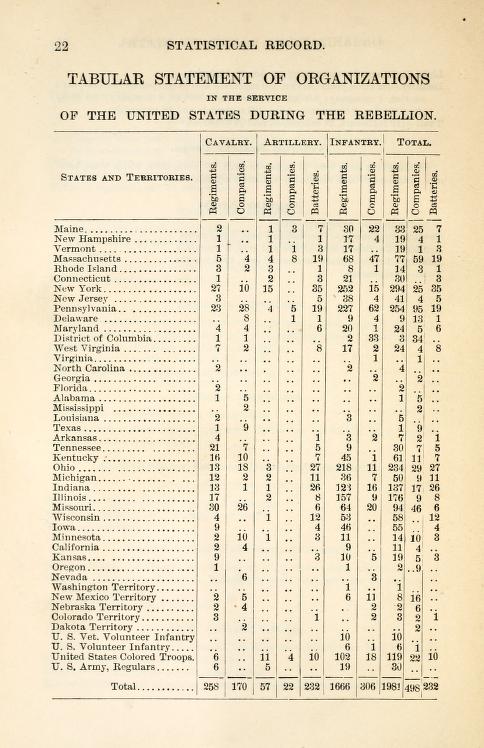

(R) Phisterer, Frederick. Statistical Record of the Armies of the United

States (1883). A total count of New York's military contributions to the Union.

An accurate total count of soldiers

and sailors from any state is complex, because sailors, marines, and blacks were often not counted, and

many soldiers reenlisted and were counted a second time (and sometimes third, etc.) for the state, known as a double

count, thus skewing the state's numbers. An accurate total casualty count is also complicated because some states counted

its contributions to the U.S. Army (aka U.S. Volunteers), state militia, national guard, independent commands, soldiers who

enlisted in units from other states, reserve units, and even miscellaneous units (or units not classified).

Of

the total enlistment, more than 120,000 were foreign-born, but it is impossible to arrive at very accurate figures

as to the nativity of the individual soldiers from the state, but Phisterer has arrived at the "conclusion that of the 400,000

individuals, 279,040 were natives of the United States, and 120,960 or 30.24 percent, of foreign birth. The latter were divided

according to nationality as follows: 42,095 Irish, 41,179 German, 12,756 English, 11,525 British-American, 3,693 French, 3,333

Scotch, 2,014 Welsh, 2,015 Swiss, and 2,350 of all other nationalities." The average age of the New York soldier was 25 years,

7 months, and New Yorkers fought in every major battle and campaign of the conflict.

See also New York and the Civil War (1861-1865).

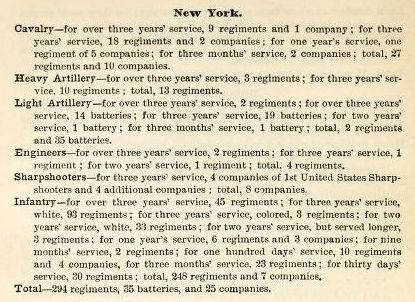

When the Civil War concluded in 1865, Phisterer, page 14, Statistical

Record of the Armies of the United States (1883), states that New York had initially provided the Union Army with 248

regiments of infantry, 27 regiments of cavalry, 15 regiments of artillery (13 heavy and 2 light), 8 companies of sharpshooters,

and 4 regiments of engineers and, as the war progressed, additional units were raised and more men were recruited

to "strengthen old organizations already in the field." Phisterer, however, on page 22, and William F. Fox, Regimental

Losses in the American Civil War (1889), concur that New York provided the Union military with 252 regiments and

15 companies of infantry, 27 regiments and 10 companies of cavalry, 15 regiments and 35 batteries of artillery, for a grand total of 294 regiments, 25 companies, and 35 batteries. Fox's numbers include navy, marines,

state militia, sharpshooters, engineers, national guard, independent units, guards, U.S. Army (aka regular army), U.S. Colored

Troops (USCT), reserve corps, units that failed to complete organization, consolidated

units, reorganized and re-designated units, ambulance corps, and misc. units. (See also Union and Confederate Army Organizations at the Beginning

of the American Civil War.)

| New York and the Civil War |

|

| The Empire State led the Union by recruiting the most units |

(Right) According to Phisterer, Statistical Record of the Armies of

the United States (1883), New York rallied, raised and recruited more men and units for the Union than any other

Northern state.

Federal

records indicate 4,125 free blacks from New York served in the Union Army, and three full regiments of United States

Colored Troops were raised and organized in the Empire State—the 20th, 26th, and 31st USCT. The 20th and 26th

Regiments of the U.S. Colored Troops were raised on Rikers Island, while the 31st USCT was raised on Hart Island. The Empire

State contributed to the Union 98 brigadier-generals, 20 major-generals, and the U.S. Secretary of State. Among the more prominent

military units from the state of New York was the Excelsior Brigade of controversial former congressman Daniel Sickles. Another well-known unit was the 11th New York Infantry Regiment, aka

First New York Fire Zouaves, but the 11th New York was often overshadowed by the 73rd New York, aka Second

Fire Zouaves, which fought at Antietam, Gettysburg, and Appomattox. Several early volunteer regiments traced their origins

to antebellum New York State Militia regiments, including the 14th Brooklyn, which became known for its bright red chasseur-style

pants.

While only 3 major generals received the Medal of Honor during the

Civil War, 2 were New Yorkers: Daniel Sickles and Julius Stahel. Although in 1859 Sickles had been charged with the murder

of Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key, he was acquitted with the first use of temporary insanity as a legal defense

in U.S. history. Sickles remains one of the most controversial Civil War generals because of his insubordination at Gettysburg.

On the other hand, Stahel, a Hungarian emigrant, had previously served as a lieutenant in the Austrian Army. During the

conflict, he commanded a cavalry division and served with valor and gallantry during the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaigns. The

3rd major general to receive the Medal of Honor was Ohioan David Stanley.

With more than 3.5 million residents, New York was

the most populous state in the Union at the outbreak of the American Civil War. Therefore, it provided a significant number

of leading generals, admirals, and politicians who were either born in New York or spent considerable time in the state before

the war. New York furnished the army with 20 major-generals, only 2 of whom — John A. Dix and Edwin D. Morgan —

were appointed from civil life. It furnished 98 officers of the rank of brigadier-general, of whom 12 were appointed from

civil life. Included in this long list of higher officers are the names of many who gained renown as among the most efficient

commanders produced by the war.

While numerous notable New Yorkers

during the Civil War include both political and military figures, the Empire State's massive population and immense contributions

during the conflict make it is difficult to recognize and pay tribute to all. Notable New Yorkers include Secretary of State

William H. Seward, Gov. Horatio Seymour, Maj. Gen. Francis C. Barlow, Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield, Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday,

Maj. Gen. James B. Ricketts, Maj. Gen. John Schofield, Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, Maj. Gen. Julius

Stahel, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, and Maj. Gen. Alexander S. Webb. Other notable New Yorkers

during the conflict include war photographer Mathew Brady, English-born artist Alfred Waud, newspaperman Horace Greeley, and

combat artist Edwin Forbes. James Wadsworth, one of the wealthiest men in the state and a former Republican candidate for

governor, was among the Union generals from New York to be killed during the war.

Several wealthy

New York industrialists played crucial roles in supporting the war effort through materiel, weapons, ammunition, supplies,

and accoutrements. Railroad impresario Cornelius Vanderbilt used his growing network of rail systems to effectively move large

quantities of troops through the state to staging and training areas.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Vanderbilt attempted to donate his largest

steamship, the Vanderbilt, to the Union Navy. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles refused it, thinking its operation and maintenance

too expensive for what he expected to be a short war. Vanderbilt had little choice but to lease it to the War Department,

at prices set by ship brokers. When the Confederate ironclad Virginia (popularly known in the North as the Merrimack) wrought

havoc with the Union blockading squadron at Hampton Roads, Virginia, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and President Abraham

Lincoln called on Vanderbilt for help. This time he succeeded in donating the Vanderbilt to the Union navy, equipping it with

a ram and staffing it with handpicked officers. It helped contain the Virginia, after which Vanderbilt converted it into a

cruiser to hunt for the Confederate commerce raider Alabama, captained by Raphael Semmes. Vanderbilt also outfitted a major

expedition to New Orleans. But he suffered a personal loss when his youngest son and heir apparent, George Washington

Vanderbilt, a graduate of the United States Military Academy, fell ill and died without ever seeing combat. While Confederate

President Jefferson Davis was imprisoned following the war, Vanderbilt, with conciliation, offered to pay Davis’ bond.

Early in the war, the Union Navy contracted with U.S. Congressman Erastus

Corning's iron works to manufacture parts and materials for the USS Monitor, the Navy's first ironclad warship. The Brooklyn

Navy Yard was an important shipbuilding and naval maintenance concern.

Foundrymen Robert Parrott and his brother Peter produced significant quantities

of artillery pieces and munitions, and their Parrott rifle, an innovative rifled gun, was manufactured in several sizes at

the West Point Foundry. The foundry's operations peaked during the Civil War due to military orders: it had a workforce of

1,400 people and produced 2,000 cannon and three million shells. Parrott also invented an incendiary shell which was used

in an 8-inch Parrott rifle (the "Swamp Angel") to bombard Charleston. The importance of the foundry to the war effort can

be measured by the fact that President Abraham Lincoln visited and inspected it in June 1862.

The National Arms Company in Brooklyn produced firearms, including large

quantities of revolvers. Other important producers of weaponry and munitions were the Federal government's Watervliet Arsenal

and the privately-owned Remington Arms Company of Ilion.

| New York, Border States, and South Secession Map |

|

| New York and Secession of Southern States Map |

| New York State Military Museum |

|

| 69th New York Regimental Color |

Although New York provided more

soldiers during the Civil War than any other Northern state, a war was not in the state's best interest because much of New

York's trade was based on moving Southern goods. New York's large Democratic community feared the impact of Abraham Lincoln's

election in 1860, but by the time of the Battle of Fort Sumter (April 1861) the political differences had vanished and the state quickly met Lincoln's request for soldiers and supplies.

(Right)

69th New York Infantry. This blue silk regimental color attributed to the 69th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment,

attached to the famed Irish Brigade, features the Arms of the United States painted in the center with

32 gold-colored, painted stars from an original 34-star pattern. Approximately 10% of the flag is lost, mostly in the

painted sections. The 69th New York suffered more battle casualties than any other New York unit.

The citizens of the North had been much aroused over the continual

shipment of war material to the Southern states and an acrimonious correspondence over a question of this kind took place

in February of 1861 between the governors of New York and Georgia. The police of New York City were vigilant and had

seized 38 boxes of muskets about to be shipped on the steamer Monticello to Savannah, and deposited them in the state arsenal

in New York City. Gov. Brown of Georgia, on complaint being made to him by the consignees, citizens of Macon, GA., made formal

demand on the mayor of the city, and on Gov. Edwin D. Morgan (1859-1862), for the immediate delivery of the arms to G. B.

Lamar, named as the agent of Georgia. There was some delay in adjusting the matter, and Gov. Brown, on Feb. 5, ordered the

seizure of five vessels, owned in New York but then in the harbor of Savannah, by way of reprisal. Three days later they were

released, but reprisals were again ordered on the 21st, when additional shipping from New York was seized at Savannah, to

be held pending the delivery of the invoice. Gov. Brown made renewed demands on Gov. Morgan for the arms and the New York

executive replied: "I have no power whatever over the officer who made the seizure, and had no more knowledge of the fact,

nor have I any more connection with the transaction, than any other citizen of this state; but I do not hesitate to say that

the arms will be delivered whenever application shall be made for them. Should such not be the case, however, redress is to

be sought, not in an appeal to the executive authority of New York to exercise a merely arbitrary power, but in due form of

law, through the regularly constituted tribunals of justice of the state or of the United States, as the parties aggrieved

may elect. It is but proper here to say, that the courts are at all times open to suitors, and no complaint has reached me

of the inability or unwillingness of judicial officers to render exact justice to all. If, however, the fact be otherwise,

whatever authority the constitution and laws vest in me, for compelling a performance of their duty, will be promptly exercised."

The matter was finally adjusted by the delivery of the arms on March 16 to the agent

of Georgia.

| New York and the Irish Brigade |

|

| The Famed Irish Brigade History |

On April 15, 1861, however,

President Lincoln issued a proclamation, known as Lincoln's Call For Troops, calling for 75,000 militia to serve for three months to suppress

the rebellion in the Southern states. The quota assigned to New York was seventeen regiments of 780 men each, or 13,280

men. The National Guard of the state responded to the call to arms with the utmost enthusiasm and were only animated by a

rivalry as to which organization could first secure marching orders. And indeed there was urgent need of haste. Gov. Morgan

had been advised by the war department that the men were wanted for immediate service and that some of the troops were at

once needed at the capital. In the hope of capturing Washington, the enemy had severed all communication by telegraph and

railroad between that city and the North, and were even attempting to prevent all supplies from reaching that city from the

surrounding country.

New York had long played an important role in the U.S. military, with

the United States Military Academy in West Point providing a significant number of officers to the antebellum Regular Army.

New York Harbor was ringed with several military outposts, forts, and garrisons, and many officers who were prominent during

the war had spent considerable time in New York before the conflict erupted in early 1861. MacDougall Hospital at Fort Schuyler

would become a leading war-time military hospital, and Davids' Island was a significant prisoner-of-war camp for captured

Confederates.

No actual Civil War battles were fought within the Empire State, although

Confederate agents did set several fires in New York City as an act intended to terrorize the community and build support

for the peace movement. Confederate agents attempted to burn New York City on November 25, 1864, and at least thirteen hotels,

P.T. Barnum’s Museum, Tammany Hall, and the shipping harbor were set on fire. Fortunately, the combustible chemicals

used by the agents did not work properly, and all of the buildings set on fire were saved with no lives lost.

In January 1861, New York had nominally a force of 19,000 militia, but it

possessed only about 8,000 muskets and rifles with which to arm this force, and the war department was in no condition to

supply the deficiency, as former U.S. Secretary of War, John B. Floyd (Virginia), had, with sinister motive, sent many

thousands of muskets from the Watervliet arsenal to Southern points.

The first organized unit to leave the state for the front lines was the

7th New York State Militia, which departed by train on April 19, 1861, for Washington, D.C. The 11th New York Infantry, a

two-years' regiment of new recruits, departed ten days later. Among the earliest casualties of the Civil War was Malta, New

York, native Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, who was killed in May 1861 during an armed encounter in Alexandria, Virginia.

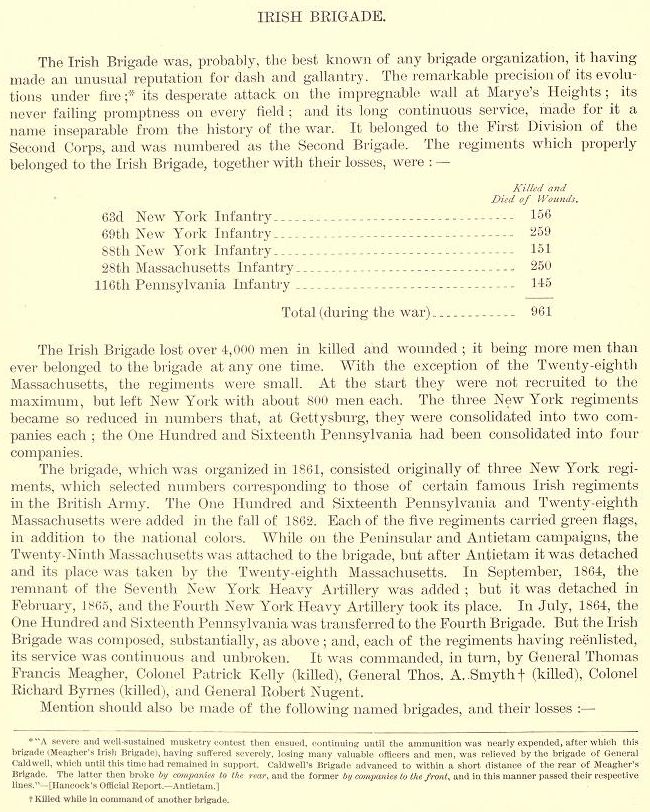

Space restricts more than a brief reference to some of the more famous

fighting organizations, such as brigades and regiments, contributed by the State of New York. Perhaps the best known

brigade organization was the Irish Brigade, officially designated as the 2nd brigade, 1st division, 2nd corps. It

was in Hancock's old division, and was successively commanded by Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher, Col. Patrick Kelly (killed),

Gen. Thomas A. Smyth (killed). Col. Richard Byrnes (killed), and Gen. Robert Nugent. It was organized in 1861, and originally

consisted of the 63d, 69th and 88th N.Y. infantry regiments, to which were added in the fall of 1862 the 28th Mass. and the

116th PA. Its loss in killed and mortally wounded (battle deaths) was 961, and a total of 4,000 men were killed and wounded

(includes died of disease, died while in Confederate prisons, and all deaths other than battle). Col. Fox in his "Regimental

Losses in the Civil War," says of this brigade: "The remarkable precision of its evolutions under fire, its desperate attack

on the impregnable wall at Marye's heights; its never failing promptness on every field;

and its long continuous service, made for it a name inseparable from the history of the war." Another famous brigade was the

Excelsior Brigade (Sickles'), belonging to Hooker's (2nd) division, 3d corps, and composed

of the 70th, 71st, 72nd, 73d, 74th and 120th N.Y. infantry. Its losses in killed and died of wounds were 876. In Harrow's

(1st) brigade, Gibbon's (2nd) division, 2nd corps, was the 82nd N.Y. Infantry Regiment. This brigade suffered

the greatest percentage of loss in any one action during the war, at Gettysburg, where its loss was 763 killed, wounded and

missing out of a total of 1,246 in action, or 61 percent. The loss of the 82nd was 45 killed, 132 wounded, 15 missing —

total, 192. There were forty-five infantry regiments which lost over 200 men each, killed or mortally wounded in action during

the war, and six of these were New York regiments. At the head of the New York regiments,

and standing sixth in the total list, was the 69th N.Y., which lost the most men in action, killed and wounded, of any infantry

regiment in the state, to-wit: 13 officers and 246 enlisted men — total, 259. Coming next in the order named were the

40th, 48th, 121st, 111th and 51st regiments. Of the three hundred fighting regiments enumerated by Col. William F. Fox,

fifty-nine were from New York. (Fox, 1889)

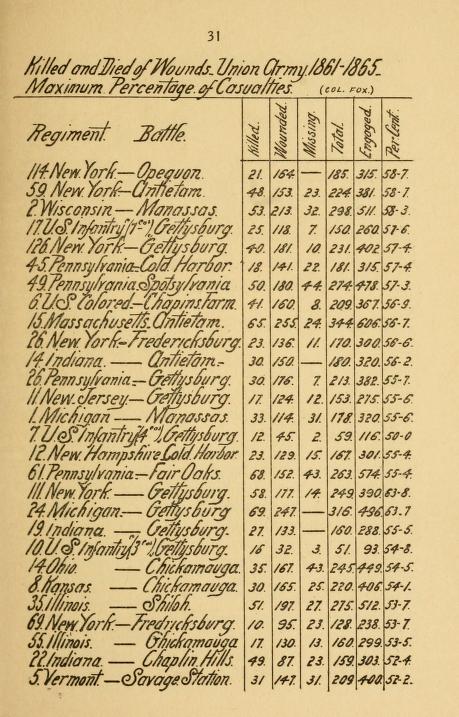

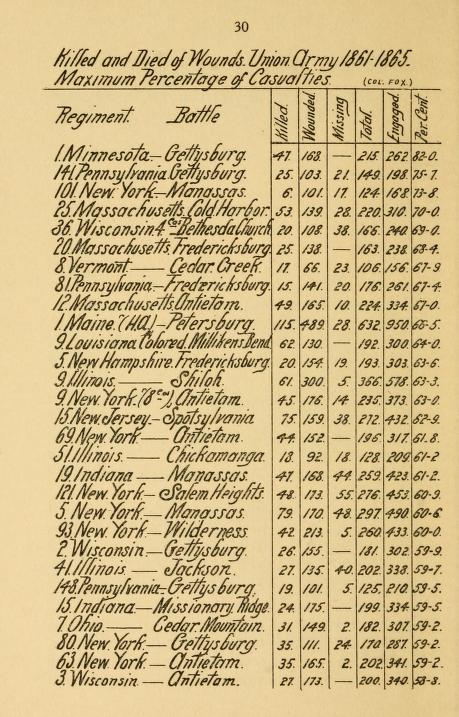

A total of 15 New York infantry regiments, such as the 69th and

111th New York regiments, suffered greater than 50% casualties during a single battle. While Infantry regiments during

the Civil War received fame and glory for their heroic charges and counterassaults, the actions of the artillery

units were often overlooked. For example, according to Dyer

(1908) and The Union Army (1908), the 8th New York Heavy Artillery received the highest combat related casualties of any New

York unit during the four year conflict. The 8th New York H.A. suffered 19 officers and 342 enlisted men (361 total) in

killed and mortally wounded (100 more than the 69th N.Y. Infantry) and 4 officers and 298 enlisted men died of disease (302

total). Grand total 663 deaths. Additionally, the 8th N.Y.H.A. suffered 37 officers and 707 enlisted men in wounded (744 total).

Killed 663; Wounded 744. Grand total casualties (killed and wounded) 1407. Statisticians applied various metrics for their

tables and totals, and one such number that was not high on their list was the total of men that died of disease. Perhaps

it was because the heroes died on the battlefields, while death by disease doesn't have the same heroic connotation.

Dying as a prisoner-of-war was also intentionally left out of many of the grand totals, for if death by disease and death

while incarcerated in Confederate prisons were counted, the 7th New York Heavy Artillery would rank first for the state, because

it lost in total deaths 677. Although the artillery units were generally stationary while in combat and therefore suffered

high casualties (including captured), they were often overrun and even engaged in fierce counterattacks. (See also Total Union and Confederate Casualties.)

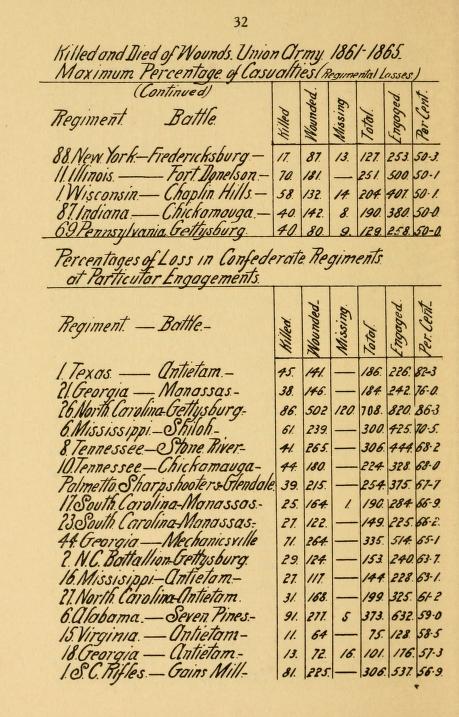

| New York's units sustained high casualty rates |

|

| Several New York units sustained high casualties in battle |

| New York and the high cost of Civil War |

|

| New York's Casualties and Killed during the Civil War |

The 69th, for example, suffered

61.8% casualties while in the thick of the fight at Antietam (September 1862) and subsequently suffered 53.7% casualties

of the total engaged at Fredericksburg in December 1862. During the conflict, while the New York unit that charged

the parapet and captured the enemy's flag was romanticized and glorified, the 85th

New York Infantry received barely a nod as disease killed "326 of its soldiers," according to Dyer (1908). According

to Phisterer, New York in the War of the Rebellion, 3rd ed. Albany: J. B. Lyon Company (1912), the 85th lost 342

to "disease and other causes." The Union Army (1908), furthermore, states that the 85th "lost 36 members by death from wounds,

103 from accident or disease, and the 222 who died in prison." The 85th, nevertheless, had suffered one of the greatest

losses of any New York unit during the war. According to Dyer, The 100th New York Regiment (aka 2nd Regiment, Eagle

Brigade), meanwhile, suffered a total of 397 in total deaths: 12 Officers and 182 Enlisted men in killed and mortally

wounded and 1 Officer and 202 Enlisted men died from disease.

In total combat related deaths

during the Civil War, the 69th New York Infantry suffered the greatest loss of any New York regiment. Out of more than 2,000

regiments that served with the Union Army, only five regiments lost more men than the 69th. When including total deaths

during the course of the war, meaning additional deaths from disease, prisoners-of-war, and "other than combat related

deaths," the 40th New York Infantry suffered the second greatest loss of any unit from the Empire State. It lost 410

men. Although numerous New York units suffered more than 300 casualties during the conflict, the following figures

indicate the state's greatest or highest regimental combat losses:

New York regimental combat losses (aka battle or action losses) by

totals:

1) 69th New York Infantry Regiment, aka 1st Regiment of the Irish Brigade, lost during service 13 Officers and 246 Enlisted men in killed and mortally wounded and 142 Enlisted men

died from disease. Total 401. (Fox, 1889; Dyer, 1908). According to Phisterer (1912), the 69th, during its service, "lost

by death, killed in action, 8 officers, 154 enlisted men; of wounds received in action, 5 officers, 94 enlisted men; of disease

and other causes, 2 officers, 149 enlisted men; total, 15 officers, 397 enlisted men; aggregate, 412; of whom 1 officer

and 63 enlisted men died in the hands of the enemy." Total 412. Regarding the 69th, The Union Army (1908) (vol.

2) also indicates that "261 died from wounds and 151 from other causes, 63 dying in prisons." Total 412.

2) 40th New York Infantry Regiment, aka Mozart Regiment or Constitution

Guard, suffered 10 Officers and 228 Enlisted men in killed and mortally wounded and 2 Officers and 170 Enlisted men died from disease.

Total 410.

3) 48th New York Infantry Regiment (Continental Guard or Perry's Saints)

suffered 18 Officers and 218 Enlisted men in killed and mortally wounded and 2 Officers and 131 Enlisted men by disease.

Total 369.

4) 121st New York Infantry Regiment Infantry (Orange and Herkimer Regiment)

lost during service 14 Officers and 212 Enlisted men in killed and mortally wounded and 4 Officers and 117 Enlisted men by

disease. Total 347.

5) 111th New York Infantry Regiment Infantry lost during service 10 Officers

and 210 Enlisted men in killed and mortally wounded and 2 Officers and 178 Enlisted men by disease. Total 400. During

the 111th Regiment's time in service, total enrollment was 1,780 soldiers. Ten officers and 210 men were killed and mortally

wounded in battle. The total of 220 men who were killed and died of wounds is only exceeded by four other New York regiments

— the 69th, 40th, 48th and 121st. In the entire Union Army, that number is only exceeded by 24 other regiments. It should

be noted that 2 officers and 74 men died while in the confinement of Confederate prisons. 111th New York is mentioned

on the monument at Gettysburg: "Arrived early morning July 2nd 1863, position near Ziegler's Grove. Went to relief of 3rd Corps in afternoon; took this position that evening and held it to close of battle. Number engaged

(8 companies) 390. Casualties: Killed 58, wounded 177, missing 14, total 249."

6) 51st New York Infantry Regiment (aka Shepard Rifles) lost 9 Officers

and 193 Enlisted men in killed and mortally wounded and 2 Officers and 174 Enlisted men by disease. Total 378.

| New York Civil War Artillery |

|

| New York artillery units suffered heavy casualties |

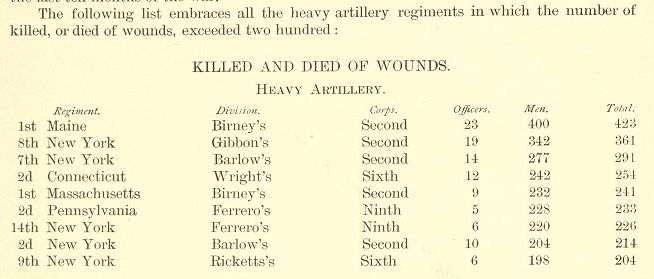

(R) Fox, William F. Regimental Losses in the American

Civil War (1889). According to Fox, during the Civil War, of the 9 heavy artillery units from the Northern states that suffered more than 200 in killed

and mortally wounded, 5 were from New York.

By mid-July 1861, New York had organized and sent 8,534 men for

three months' service; 30,131 two years' volunteers and 7,557 three years' volunteers — a total of 46,224 officers and

men. The disastrous First Battle of Bull Run, July 21, demonstrated that the war was

to be a long one, and in July Congress authorized the president to accept the services of volunteers for three years.

By the end of 1861, New York had fielded 107,000 military volunteers.

The State of

New York continued its tremendous exertions in support of the Federal government and continued to supply both men and money

with a lavish hand. The record of troops furnished for the year 1862 or up to the close of Gov. Morgan's administration,

is as follows: twelve regiments of infantry (militia), for three months, 8,588 men; one regiment of volunteer infantry, for

nine months, 830 men; volunteers for three years, one regiment of cavalry, 1,461 men; two regiments, four battalions, and

fourteen batteries of artillery, 5,708 men, and eighty-five regiments of infantry, 78,216 men; estimated number of recruits

for regiments in the field, 20,000; incomplete organizations still in the state, 2,000 men; total for 1862, 116,803; total

since the beginning of the war, 224,081. To obtain the full number of men furnished by the state, there should be added

to the above, 5,679 men enlisted in the regular army, and 24,734 in the U.S. Navy and Marines, making the total number furnished,

254,494.

The sons of the Empire State were to be found in every important naval engagement throughout

the war. That they paid the debt of patriotism and valor is attested by the fact that 1,880 perished in battle, from disease

and from other causes incident to the service. When the government was in pressing need of more vessels, a son of New York,

Commodore Vanderbilt, presented it with his magnificent ship, the Vanderbilt costing $800,000. The names of John Ericsson,

John A. Griswold and John F. Winslow, all of New York, are inseparably linked with the most important contribution to the

navy during the war — the building of the Monitor — which worked a revolution in naval warfare.

| New York Civil War History in Casualties & Killed |

|

| 88th New York Infantry suffered 50% losses at Fredericksburg |

New York troops were prominent in virtually every major battle in the Eastern

Theater, and some New York units participated in leading campaigns in the Western Theater, albeit in significantly smaller

numbers than in the East. New Yorker John Schofield rose to command of the Army of the Ohio and won the Battle of Franklin,

dealing a serious blow to Confederate hopes in Tennessee. More than 27,000 New Yorkers fought in the war's bloodiest battle,

the three-day Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863; 989 of these men were killed in action, with 4,023 wounded (several of which

died of their wounds in the months following the battle). 1,761 New Yorkers were taken as prisoners of war, and many were

transported to Southern prisons in Richmond, Virginia, and elsewhere. It was the largest number of casualties for New York

troops in any battle.

Among the scores of officers from New York to perish at Gettysburg was

Brig. Gen. Samuel K. Zook, a long-time resident of New York City. Col. Patrick "Paddy" O'Rourke of Rochester died a hero while

leading the 140th New York Infantry into action on Little Round Top. Col. Augustus van Horne Ellis was killed near the Devil's Den on July 2; he was later memorialized with the only full-sized statue of a regimental commander to be erected on the battlefield.

On May 5, 1863, Clement L. Vallandigham, former Congressman of Ohio, was arrested as a violator

of Union General Order Number 38, which forbade expressing sympathy for the enemy. Vallandigham's charges included saying

two words: "King Lincoln." Vallandigham was tried by a military court on May 6 and 7, and was charged by the Military Commission

with "Publicly expressing, in violation of General Orders No. 38, from Head-quarters Department of the Ohio, sympathy for

those in arms against the Government of the United States, and declaring disloyal sentiments and opinions, with the object

and purpose of weakening the power of the Government in its efforts to suppress an unlawful rebellion." He was sentenced to confinement in a military prison "during the continuance of the war" at Fort Warren.

Controversy and protests ensued throughout the North. On May 16, 1863, there was a meeting at Albany, New York, to

protest the arrest of Vallandigham. "A letter from Governor Horatio Seymour of New York was read to the massive crowd." Seymour

charged that "military despotism" had been established and that "It is an act which has brought dishonor upon our country;

it is full of danger to our persons and to our homes; it bears upon its front a conscious violation of law and justice. Acting

upon the evidence of detailed informers, shrinking from the light of day in the darkness of night, armed men violated the

home of an American citizen and furtively bore him away to a military trial, conducted without those safeguards known to the

proceedings of our military tribunals. The action of the administration will determine in the minds of more than one-half

of the people of the loyal states, whether this war is waged to put down rebellion at the South, or to destroy free institutions

at the North. We look for its decision with the most solemn solicitude." Resolutions by the Hon. John V. L. Pruyin were adopted.

The resolutions were sent to President Lincoln by Erastus Corning. As a result, Union Gen. Burnside suppressed publication

of the New York World, which had reported on the meeting in Albany.

On May 30, 1863, there was a meeting at Military Park in Newark, New Jersey. A letter from New Jersey Governor Joel

Parker was read. His letter condemned the arrest, trial and deportation of Vallandigham, saying they "were arbitrary and illegal

acts. The whole proceeding was wrong in principle and dangerous in its tendency." On June 1, 1863, there was a protest meeting

in Philadelphia.

In response to a public letter issued at the meeting of angry Democrats in Albany, Lincoln's "Letter to Erastus Corning

et al." of June 12, 1863, explains his justification for supporting the court-martial's conviction. President Lincoln wrote

the "Birchard Letter" of June 29, 1863, to several Ohio congressmen, offering to revoke Vallandigham's deportation order if

they would agree to support certain policies of the Administration. Lincoln, who considered Vallandigham a "wily agitator",

was wary of making him a martyr to the Copperhead cause and thus ordered him sent through the enemy lines to the Confederacy.

Although he altered Vallandigham's sentence, Lincoln did not repudiate Burnside's military actions against a civilian.

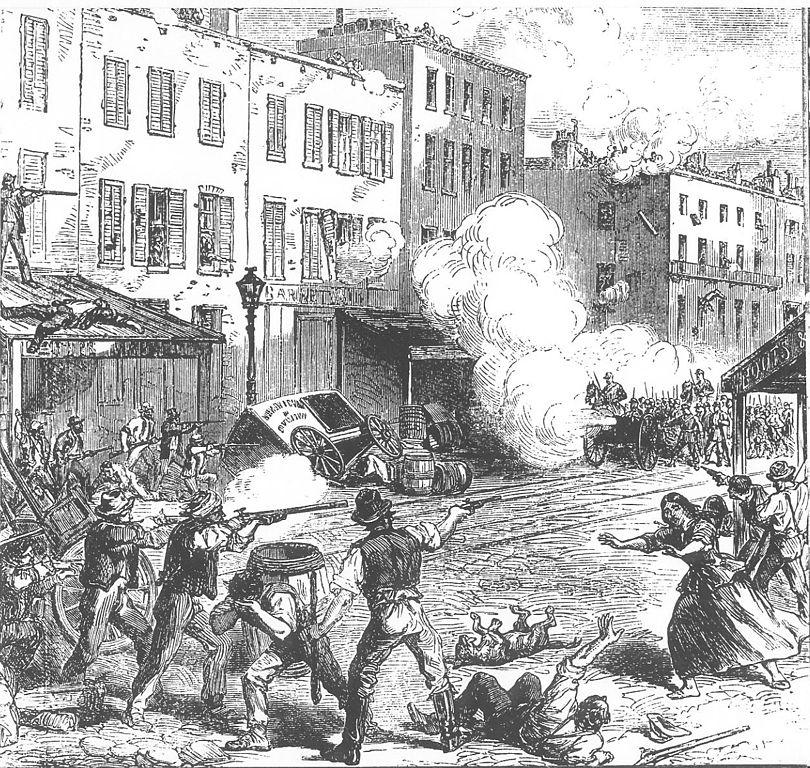

The first important draft of the war took place during July and Aug.,

1863, when the state was virtually stripped of its militia, and proved to be one of the most exciting questions which the

new administration of Gov. Seymour was called upon to meet. Under the act of Congress, approved March 3, 1863, prescribing

a method of drafting men for the military service, whenever needed, all enlistments under the draft and also for volunteers

after May 1, were placed in the hands of a provost marshal-general, assisted by an acting assistant provost-marshal-general,

in each of the three districts, northern, southern, and western, into which the state

was divided. The draft was commenced in New York City on July 11, and was accompanied by a riot of very of serious proportions

on the 13th. To quell the riot, in which all the rowdy, turbulent elements of the city took part, all the available state

troops were ordered to New York City. These, assisted by all the troops in the city and harbor and a few outside organizations,

together with the city police force, succeeded in dispersing the angry mobs and quiet was finally restored on the 17th. No

serious disturbances occurred elsewhere, though violence was only prevented in one or two places by the presence of troops.

The 1863 New York City Draft Riots, known at the time as Draft Week, were

caused chiefly by Irish immigrants and their descendants, who attacked African Americans and their property in New York City.

Records indicate that they killed 100 blacks and burned many buildings to the ground, including the Colored Orphans Asylum

at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue. The children escaped harm, aided by Union troops in the city. The Irish resented being drafted

for the American Civil War when wealthier men could pay for substitutes. They resented having to fight, as they saw it, on

behalf of people with whom they competed daily for wages in low-skilled jobs.

The city's strong commercial ties

to the South, its growing immigrant population, and anger about conscription led to divided sympathy for both the Union

and Confederacy, culminating in the Draft Riots of 1863, one of the worst incidents of civil unrest in American history. The

week of July 11 to July 16, 1863 was known at the time as "Draft Week". Many citizens were upset with new laws passed by Congress

to draft men to fight in the unpopular war. The ensuing disturbances were the largest civil insurrection in American history

apart from the Civil War. President Lincoln sent several regiments of militia and volunteer troops to control the city. The

rioters numbered in the thousands and were mainly Irish Americans. Smaller-scale riots erupted in other cities throughout

the North, including in other places in New York State, at about the same time.

The exact death toll during the New York City Draft Riots is unknown,

but estimates indicate nearly 1,000 civilians (including 100 blacks) were killed and at least 2,000 more were injured.

Total property damage was nearly $2 million. Historian Samuel Morison wrote that the riots were "equivalent to a Confederate

victory". The city treasury later indemnified one-quarter of the amount. During the rioting, fifty buildings, including two

Protestant churches, burned to the ground. On August 19, the draft was resumed.

| New York Draft Riots in 1863 |

|

| Depiction of New York Draft Riots in 1863. The Illustrated London news, ca. 1863. |

During the year 1864, a voluminous correspondence took place between Gov.

Seymour and the war department relative to the proper credits to be allowed the state under the calls of this year. The state

and Federal accounts as to the number of men furnished by the state since the beginning of the war were harmonized after July

1864, when the state was finally allowed credit, especially for the many thousands of patriotic men enlisted in the regular

army and in the U.S. Navy and marine service. During the year New York furnished a total of 162,867 men, divided as follows:

militia for 100 days' service, 5,640; for 30 days' service, 791; volunteers enlisted by the state authorities, 17,261; reenlisted

in the field, 10,518; drafted men, substitutes, enlistments and credits by provost-marshals, 128,657. During the two years

of Gov. Seymour's administration, the Empire State furnished the government a total of 214.075 men. Included in the above

number are three regiments of U.S. Colored Troops, designated the 20th, 26th and 31st regiments of infantry. All three regiments

were organized in 1864 for three years' service.

Under the last call for troops, Dec. 19, 1864, the president asked for 300,000

men to serve for three years and the quota assigned to New York was 61,076. The long war was now drawing to a close and all

recruiting and drafting ceased April 14, 1865.

On April 3, 1865, word was received in New York announcing the evacuation

of Petersburg and the fall of Richmond. Universal excitement and rejoicing prevailed from this time forward until the final

surrender of Lee on the 9th, which practically terminated the war. On the 26th occurred Johnston's surrender and soon after

the remaining forces of the Confederates laid down their arms. The work of disbanding the Union armies was then taken up and

by the close of the summer nearly all the survivors of the New York troops came home, only a few regiments remaining in the

service on special duty until the following year. The war-worn veterans were received on their return with every honor that

a grateful people could bestow for their heroic services.

On June 7 Gov. Fenton (1865-1868) congratulated the soldiers of the

state in an eloquent address which touched the hearts of all, saying: "Soldiers of New York: Your constancy, your patriotism,

your faithful services and your valor have culminated in the maintenance of the government, the vindication of the constitution

and the laws and the perpetuity of the Union. You have elevated the dignity, brightened the renown, and enriched the history

of your state. You have furnished to the world a grand illustration of our American manhood, of our devotion to liberty, and

of the permanence and nobility of our institutions. Soldiers: your state thanks you and gives you the pledge of her lasting

gratitude. She looks with pride upon your glorious achievements and consecrates to all time your unfaltering heroism. To you

New York willingly intrusted her honor, her fair name and her great destinies; you have proved worthy of the confidence imposed

in you and have returned these trusts with added luster and increased value. The coming home of all our organizations, it

is hoped, is not far distant. We welcome you and rejoice with you upon the peace your valor has achieved. Your honorable scars

we regard as the truest badges of your bravery and the highest evidences of the pride and patriotism which animated you. Sadly

and yet proudly we receive as the emblems of heroic endurances your tattered and worn ensigns, and fondly deposit these relics

of glory, with all their cherished memories and endearing associations, in our appointed repositories. With swelling hearts

we bade Godspeed to the departing recruit; with glowing pride and deepened fervor we say welcome to the returning veteran.

We watched you all through the perilous period of your absence, rejoicing in your victories and mourning in your defeats.

We will treasure your legends, your brave exploits, and the glorified memory of your dead comrades, in records more impressive

than the monuments of the past and enduring as the liberties you have secured. The people will regard with jealous pride your

welfare and honor, not forgetting the widow, the fatherless, and those who were dependent upon the fallen hero. The fame and

glory you have won for the state and nation, shall be transmitted to our children as a most precious legacy, lovingly to be

cherished and reverently to be preserved."

The efforts put forth by the great State of New York throughout the war were in every way worthy

of her commanding position among the states of the Union, where she easily ranked first in population and material resources.

New York furnished the most men and sustained the heaviest loss of any state in the war. The final report of the adjutant-general

at Washington for the year 1885 credits New York with 467,047 troops, including 6,089 men in the regular army, 42,155 sailors

and marines; and 18,197 who paid commutation. As the above report of the adjutant-general of the U.S. Army shows that there

were 2,865,028 men furnished during the war, under all calls, the enlistments credited to New York represent over 16 percent,

of the total.

| New York State Military Museum |

|

| 111th New York Infantry Regiment Guidon |

(Right) 111th New York Infantry Regiment Guidon. This silk swallowtail guidon,

used as a marker to assist in battlefield maneuvers, conforms to the “stars and stripes” pattern described in

General Order No. 4, Headquarters of the U.S. Army, dated January 18, 1862. Deposited into the collection in July 1865, this

fragile flag’s blue canton has faded significantly. Note the cloth identification label, possibly added in July 1865,

at the bottom hoist. The 111th fought in numerous major battles, including the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House, and it suffered 249 casualties at Gettysburg in July 1863.

"No men were credited to

New York for service in the navy and marine until Feb., 1864, and then credit was received for 28,427, as having been enlisted

in the state since April 15, 1861. The adjutant-general of the United States army, under date of July 15, 1885, credits New

York with 35,144 enlistments in the navy, which includes no doubt those enlisted in the marine corps, a few hundred only.

From the statements of the assistant provost-marshals-general it appears, however, that they credited the state with 41,380

such enlistments. The secretary of the navy, under date of April 10, 1884, in a communication to the United States senate,

reported the number enlisted in the navy between April 15, 1861, and Feb. 24. 1864, to have been 67,200, of whom there were

credited to this state 28,427 men; that the number enlisted between Feb. 24,

1864, and June 30, 1865, was 37,577, of whom were credited to this state, 13,728; that the number enlisted during the

war, but not credited to any state was 20,177, of whom were enlisted in this state, 6,817, making the total number of men,

who served in the navy, not including those in service April 15, 1861, 124,954, of whom 39.192 per cent., or 48,972 are due

to New York. This report of the secretary of the navy, although it places the number credited to this state at a higher figure

than even the records of the assistant provost-marshals-general, is here accepted as the correct statement. But to it must

be added the number of men in service April 1, 1861, which an annual report of the navy places at 7,600 men; and of this number

there is claimed as due to this state the same percentage as has been found of those enlisted between April 15, 1861, and

June 30, 1865, namely 39.192 per cent., or 2,964. This would make the total number who served in the navy during the war,

132,554, of whom there came from this state, 51,936. As with the regular army, so were for a time volunteers permitted to

enlist in, or to be transferred to the navy, and it is estimated that at the most 1,000 men were thus transferred, and these

require to be deducted from the claims made here for additional credit. It is accepted as a fact that 42,155 men were duly

credited to New York, and the remainder, deducting those transferred from the volunteers, of 8,781 men is fairly due the state."

(The Union Army, 1908)

Of the 502,765 men (includes reenlistments or double counts) furnished by the state,

17,760 served in the regular army, and 50,936 in the United States navy and marine corps, as above shown; the remainder were

distributed as follows: In the United States volunteers, 1,375 of whom 800 are estimated to have been transferred from the

volunteers as general and staff officers, giving this branch of the service only 575; in the United States veteran volunteers,

1,770; in the veteran reserve corps, 9,862, but as most of these men are properly credited to the volunteers, where they originally

enlisted, the state only received credit for reenlistments in this branch of the service to the number of 222; in the United

States colored troops, 4,125; in the volunteers of other states (estimated), 500; in the militia and National Guard, 38,028;

men who paid commutation, for which the state was officially credited, 18,197; in the general volunteer service, 370,652.

The enlisted men were divided according to their terms of service as follows: For 30 days, 15,266;

for three months, 17,743; for 100 days, 5,019; for nine months, 1,781; for one year, 62,500; for two years, 34,723; for three

years, 347,395; for four years, 141; paid commutation, 18,197 — total, 502,765. As a large number of men enlisted in

the service more than once, the actual number of individuals from New York who served during the war has been estimated in

round numbers at 400,000. The population of the state in 1860 was 3,880,735, of whom 1,933,532 were males. The percentage

of individuals in service to total population is therefore 10.30; of individuals to total male population, 20.68. It has been

found impossible to arrive at very accurate figures as to the nativity of the individual soldiers from the state, but Phisterer

has arrived at the conclusion that of the 400,000 individuals, 279,040 were natives of the United States, and 120,960 or 30.24

percent, of foreign birth. The latter were divided according to nationality as follows: 42,095 Irish, 41,179 German, 12,756

English, 11,525 British-American, 3,693 French, 3,333 Scotch, 2,014 Welsh, 2,015 Swiss, and 2,350 of all other nationalities.

To the loyal and patriotic women of the state is largely due the final successful

outcome of the war, and from the very beginning the mothers, wives, sisters and sweethearts of those who enlisted, exerted

themselves in every way to alleviate the sufferings and hardships of the soldiers. Every city, town and village had its relief

association, which labored unceasingly in making and forwarding comforts to the soldiers in the field, and in providing hospital

supplies for the sick and wounded. At the very beginning of the struggle a society was organized in New York city to furnish

hospital supplies and other needed comforts for the soldiers in field and hospital. The first meeting was held in the church

of the Puritans, which later culminated in a great assemblage of 3,000 ladies in the Cooper Institute to adopt a plan of concerted

action for bringing relief to suffering soldiers, and to their bereaved relatives and friends. This great Cooper Union meeting

resulted in the formation of a Woman's central relief association, which then took charge of most of the active relief work.

The headquarters of the association were in New York, and It formed an efficient auxiliary to the general hospital service

of the army, and it is no exaggeration to say that many thousands of sick and wounded soldiers owe their lives to the efforts

of this splendid relief association. At a later date, when the great relief associations known as the United States sanitary

and Christian commissions became perfected, the women of the state continued to act as active and efficient aids in the prosecution

of their great work, and these associations owe their very origin in a large measure to the philanthropic impulses of the

women of New York.

Another efficient agency in promoting the successful conduct of the war

was the famous Union League Club of New York city, whose influence was manifested in many ways, such as raising and equipping

regiments, aiding the general government in the floating of bond issues, and supporting the work of the Sanitary commission.

It can be stated with conviction that the great State of New York gave 'unconditional loyalty' to the Union.

Casualties

An accurate total count

of soldiers and sailors from any state is complex, because sailors, marines, and blacks were often not counted, and

many soldiers reenlisted and were counted a second time (and sometimes third, etc.) for the state, known as a double count,

thus skewing the state's numbers. An accurate total casualty count is also complicated because some states counted its contributions

to the U.S. Army (aka U.S. Volunteers), state militia, national guard, soldiers who enlisted in units from other states, reserve

units, home guard, independent commands, and even miscellaneous units (or units not classified). Thus, numbers from Phisterer,

Fox, The Union Army, and Dyer, vary.

During the conflict, according to Frederick Phisterer, New York in the War

of the Rebellion (1890), the Empire State provided more than 370,000 soldiers to the Union armies. Of these, 834

officers were killed in action, as well as 12,142 enlisted men. Another 7,235 officers and men perished from their wounds,

and 27,855 died from disease. Another 5,766 were estimated to have perished while incarcerated in Southern prisoner-of-war

camps. Phisterer indicates that New York had a grand total of 53,832 fatalities. But Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (1908), states

that during the course of the Civil War, New York suffered a total of 46,534 deaths: 19,085 in killed and mortally wounded;

19,835 died of disease; 4,710 died as prisoners-of-war; 914 died from accidents; 1,990 died from causes other than battles.

See also Total Union and Confederate Casualties.

According to The Union Army (1908), however, of the total number

of individuals from New York who served in the army and navy of the United States during the war, the state claims a loss

by death while in service of 52,993. Of this number, there were killed in action, 866 officers, 13,344 enlisted men, aggregate

14,210; died of wounds received in action, 414 officers, 7,143 enlisted men, aggregate 7,557; died of disease and other causes,

506 officers, 30,720 enlisted men, aggregate 31,226; total, 1,786 officers, 51,207 enlisted men. The adjutant-general of the

United States in his report of 1885 only credits the state with the following loss: killed in action, 772 officers, 11,329

enlisted men, aggregate 12,101; died of wounds received in action, 371 officers, 6,613 enlisted men, aggregate 6,984;

died of disease and other causes, 387 officers, 27,062 enlisted men, aggregate 27,449; total, 1,530 officers, 45,004 enlisted

men, aggregate 46,534. Of these 5,546 officers and men died as prisoners. The above report, however, only includes losses

in the militia, National Guard and volunteers of the state, and fails to include the losses in other branches of the service,

including those who served in the navy and marine corps, and in the colored troops. Of the 51,936 men furnished by the state

to the navy, 706 were killed in battle, 997 died of disease, 36 died as prisoners, and 141 from all other causes — total,

1,880. See also New York and the Civil War (1861-1865).

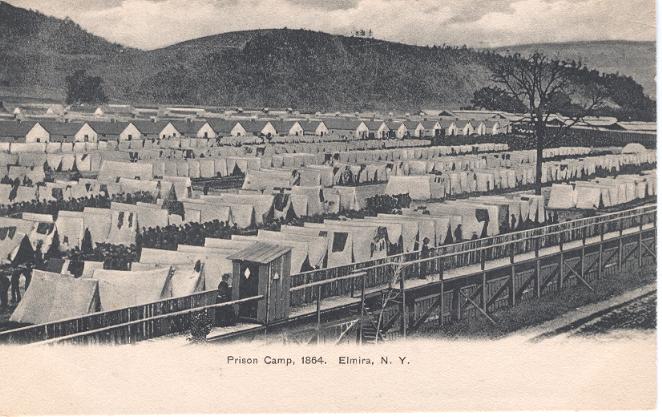

| Elmira Prison, New York |

|

| Elmira Prison Camp |

Castle Williams

Castle Williams, aka Castle Williams Prison, was designed and erected between

1807 and 1811 under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel (later Colonel) Jonathan Williams, Chief Engineer of the Corps of

Engineers and first Superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. The castle was one component

of a defensive system for the inner harbor that included Fort Columbus (later renamed Fort Jay) and the South Battery on Governors

Island; Castle Clinton at the southern tip of Manhattan; Fort Wood on Liberty Island; and Fort Gibson on Ellis Island.

As many as 1,500 Confederate prisoners were detained at Castle Williams

and records indicate that only 47 prisoners died during the course of the Civil War.

Castle Williams is a circular fortification of red sandstone on the northwest

point of Governors Island, part of a system of forts designed and constructed in the early 19th century to protect New York

City from naval attack. Castle Williams served during the 1860s as a defensive fortification, a barracks for the garrison

quartered on Governors Island, and a prison for Confederate prisoners and deserters from the Union Army.

Enlisted Confederate prisoners were held at Castle Williams, the officers

in the barracks at Fort Columbus. Later histories have stated that as many as 1,000 to 1,500 men were imprisoned at Castle

Williams at one time. While this may have been the case for a few weeks in June 1862, the usual occupancy was much less, according

to the documentary records. Surgeon William Sloan reported that 630 ailing Confederate prisoners were being held in substandard

conditions at Castle Williams in September 1861. All but the sickest were transferred to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor the

following month. It was not until April of the following year that prisoners were again housed at the castle.

Post commander Colonel Loomis wrote in May 1862 of 499 noncommissioned officers,

prisoners of war, who were on Governors Island—most presumably held at Castle Williams. Another 539 prisoners arrived

in early June, thus crowding the island with more than 1,000 prisoners. This condition did not last long, however, since only

486 prisoners were reported as being present by the end of June in the first official “Monthly Abstract from Monthly

Returns of the Principal U.S. Military Prisons” dated July 1862. Most had been transferred by the end of July, leaving

no prisoners at Post Fort Columbus for the remainder of 1862, except in September when five were noted.

The year 1863 was comparatively quiet, with only 15 prisoners held in June

and July, 14 in August, and 13 in September. Colonel Hoffman, Commissary- General of Prisoners, visited Governors Island in

December 1863. He described Castle Williams as then being used primarily for deserters from the Union Army and only occasionally

for prisoners of war, with a maximum capacity of 500.

More activity occurred in 1864, with eight prisoners recorded on the island

in January, 78 in February, 301 in September, 303 in October, 316 in November, and 34 in December. As in previous months,

no breakdown was provided as to the number held at Castle Williams versus those at the barracks at Fort Columbus. Prison activity

slowed in the final months of the war, the number of prisoners at Governors Island dwindling to 135 in January 1865, 126 in

February, 9 in March, and finally none in April.

A few physical descriptions exist of Castle Williams for the years 1861-

65. Colonel Loomis wrote in September 1861 that the second and third tiers were then occupied by prisoners. Surgeon William

Sloan described the crowded castle that same month as being ill-ventilated with no cooking facilities, no heating in the lower

tier, and no privies. The poorly clothed prisoners were reported as having measles, typhoid fever, pneumonia, and intermittent

fevers.

Remodeling of Castle Williams may have occurred during the early months

of 1862 after the island had been cleared of all prisoners, judging from a letter dated March 1862 by General Joseph Totten,

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who noted the castle was “nearly ready for imprisonment of captured Confederate troops.”

No details of this work have yet been found. Prisoners shared their space with guns in the second- tier casemates, according

to a letter dated April 1862, which curtailed the use of the castle as a defensive work. Installation of temporary bunks for

the prisoners was suggested in June of that year, although it is not known if these were ever provided.

Ammunition continued to be stored at the castle, as noted in a letter dated

August 1862. Alterations to the barbette tier [roof] were proposed in January 1863, most likely to accommodate new armament.

A congressional appropriation of $100,000 was made in the summer of 1864 for “construction, preservation, and repairs”

of several New York Harbor fortifications, including Castle Williams. What work, if any, was carried out at the castle is

not known. The substandard conditions of earlier years seem to have been corrected by November 1864, when an inspection report

of Castle Williams described the quarters as “clean and comfortable,” outfitted with “tubs” that served

as sinks. An exterior view of the castle from across New York Harbor is dated April 6, 1865, the last year of the war.

Elmira Prison, also known as Elmira Prison Camp, located at Elmira,

New York, was formerly used as a Union Army training base and was converted to a Union prisoner-of-war camp in 1864 with a

capacity for approximately 12,000 prisoners. During the 15 months the prison camp detained 12,123 Confederate soldiers. Nearly

25% (2,963) died from a combination of malnutrition, continued exposure to harsh winter weather, lack of medical care, poor

sanitary conditions, and disease. The camp's dead were prepared for burial and laid to rest at what is now Woodlawn National

Cemetery. At the end of the war, each Confederate prisoner was required to take a loyalty oath and then was given a train

ticket home. The last prisoner vacated the camp on September 27, 1865, and subsequently the camp was closed, demolished and

converted to farm land.

| New York Civil War Map of Battles & Battlefields |

|

| Large High Resolution Map of New York |

Fort Lafayette, aka Fort Lafayette Prison, had served as a U.S. military

prison since July 15, 1861, [when] Edward D. Townsend, assistant adjutant general, ordered Major General Nathaniel P. Banks

to take prisoners captured by General McClellan in West Virginia. Townsend then advised, "A permanent guard will be ordered

to the fort in time to receive the prisoners." The first POWs arrived July 22. Prior to this, the fort had served as one of

the first Northern coastal fortifications to hold Federal political prisoners.

The fort was built on a small rock island lying in the Narrows between

the lower end of Staten Island and Long Island, opposite Fort Hamilton. All POWs en route to Fort Lafayette arrived at Fort

Hamilton first, where they were searched, had their names recorded, and were placed on a boat for the quarter-mile trip to

the offshore island prison. Erected in 1822 and originally named Fort Diamond, Fort Lafayette was an octagonal structure with

the four principal sides much larger than the others, making the building appear somewhat round from the outside and square

from the inside.

The fort's walls were 25 to 30 feet high, with batteries commanding

a view of the channel in two of its longer and two of its shorter sides. Two tiers of heavy guns were on each of these sides,

with lighter barbette guns above them under a temporary wooden roof. The two other principal sides were occupied by two stories

of small casemates, ten on each story. The open area within the fort was 120 feet across with a pavement 25 feet wide running

around the inside, leaving a patch of ground 70 feet square in the center.

Long before the Civil War this fortress was renamed Fort Lafayette,

in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, the young French general who had aided the American cause in the Revolutionary War.

By the second year of the Civil War, however, it would be hatefully referred to by many simply as "that American Bastille".

. . .

The prisoners were confined in the fort's two principal gun batteries

and in four casemates of the lower story that had all been converted into prison rooms by bricking up the open entrances.

. . .

The enclosures were lighted by five embrasures measuring, about 2Y2

by 2 feet, which were covered with iron gratings. Five large doorways, 7 or 8 feet high, opened upon the enclosure from within

the walls but were covered by solid folding doors. . . .

The four casemates were nothing more than vaulted cells measuring 8

feet at the highest point and 24-by-14 feet wide. Each was lighted by two small loopholes in the outer wall and one on an

inner wall. Large wooden doors of the casemates were shut and locked at 9:00 Pm. and remained so until daylight. Although

these rooms remained dark and damp most of the time, they did have fireplaces, which the batteries lacked. Later, stoves had

to be installed in the battery rooms to combat the cold.

Neither location had furniture except for a few beds. . . .

In immediate command over the Fort Lafayette prisoners was Lieutenant

Charles O. Wood, who was described as "brutal" by many of the prisoners. He had been a baggage handler on the Ohio and Mississippi

Railroad before the war and had received his commission, it was said, from President Lincoln as a reward for successfully

smuggling Lincoln's baggage through Baltimore prior to his inaugurations.

When originally converted to a prison, the fort was believed capable

of holding up to fifty POWs. From the very beginning, however, twenty were held in each battery while nine to ten were held

in each casemate. Before long there were often thirty-five to a battery and up to thirty in a casemate. . . .

When the prisoners arrived at Fort Lafayette, they were escorted to

the office of Lieutenant Wood where, again, they were searched and had their names recorded. All their money was confiscated;

they were given a receipt and then shown to their quarters.

Some of the first inmates included those who had done nothing more than

express sympathy for the South: members of the Maryland legislature; Baltimore's police commissioners; James W Ball, a New

Jersey Democrat who was later elected to the U.S. Senate; and Francis K. Howard, editor of a Baltimore newspaper and grandson

of Francis Scott Key. In addition, all officers who had resigned commissions in the U.S. Army to accept Confederate commands

were, if captured, automatically sent there.

| Liberty Island, New York City, New York |

|

| Statue of Liberty |