|

|

New York Civil War Timeline

1860 - U.S. Census. U.S. population: 31,443,321. Total number of slaves

in the Lower South: 2,312,352 (47% of total population). Total number of slaves in the Upper South: 1,208758 (29% of total

population). Total number of slaves in the Border States: 432,586 (13% of total population). Almost one-third of all Southern

families owned slaves. In Mississippi and South Carolina it approached one half. The total number of slave owners was 385,000

(including, in Louisiana, some free Negroes). As for the number of slaves owned by each master, 88% held fewer than twenty,

and nearly 50% held fewer than five. The geographical center of the United States lies somewhere near Chillicothe, Ohio. New

York City became the largest Irish city in the world with 203,740 Irish-born out of a total population of 805,651.

December 18, 1860 - Committee of Thirteen. A committee of the United States

Senate was formed to investigate the possibility of a "plan of adjustment" that might solve the growing secession crisis,

called the Committee of Thirteen because of the number of its members. The most prominent compromise, known as the Crittenden Compromise, was the submitted John J. Crittenden of Kentucky. Proposals for compromise

were also submitted by committee members Robert Toombs of Georgia, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois,

and William H. Seward of New York. However on the motion of Jefferson Davis, it was decided that no proposal would be reported

as adopted unless supported by a majority of the Republicans and a majority of the Democrats serving on the committee. Under

this restriction, the committee was unable to agree upon a satisfactory "plan of adjustment" and so reported to the Senate,

on December 31, 1860.

| New York Civil War Timeline |

|

| Secession of Southern States and Civil War |

January 11, 1861 - Resolution of New York Legislature. New York Legislature

passes anti-Southern resolution entitled Concurrent resolutions tendering aid to the President of the United States in support

of the Constitution and the Union which starts "Whereas, treason, as defined by the Constitution of the United States, exists

in one of more of the States of this confederacy; and whereas, the insurgent State of South Carolina, . . .". It goes on to

say that the N.Y. Legislature "is profoundly impressed with the value of the Union, and determined to preserve it unimpaired."

A copy of this resolution was sent to all the governors.

January 14, 1861 - Corwin Amendment. With the U.S. House Committee of Thirty-three unable to reach agreement on a compromise, Ohio Rep. Thomas Corwin,

Chairman of the House Committee of Thirty-three, proposed a constitutional amendment protecting slavery where it exists that

could never be further amended without approval of slaveholding states. In a stunning feat of linguistic legerdemain, the

Corwin committee delivered to the House floor a draft amendment to protect slavery that never mentioned the words "slave"

or "slavery" at all: "No amendment shall be made to the Constitution which will authorize or give to Congress the power to

abolish or interfere, within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or

service by the laws of said State." Significantly, the proposed amendment did not address the burning issue of moment: the

power of Congress to bar slavery from territories that were not yet states. The amendment passed the House as Joint Resolution

No. 80 on February 28 by a vote of 133 to 65, which was two-thirds of the members present. In the subsequent parliamentary

wrangle over whether that met the Constitution's requirement of two-thirds of the House, opponents of the amendment lost.

On March 2, the Senate acted in favor of the proposed amendment by a vote of 24 to 12, with anti-slavery Senator Benjamin

F. Wade of Ohio attempting to derail it—or at least to demonstrate his disgust for it—by asking unanimous consent

to vote first on a bill relating to guano deposits. Another opponent of the amendment, Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois,

lodged an appeal of the decision by Senate President Pro Tem Solomon Foot of Vermont that the vote—two-thirds of the

members present—met the Consitutional two-thirds requirement; but Trumbull joined 32 other senators in upholding the

action, leaving Wade the sole senator opposing it. A young Henry Adams observed that the measure narrowly passed both bodies

due to the lobbying efforts of Abraham Lincoln, the President-Elect. Ratification efforts began quickly after the resolution's adoption by Congress

and included a public endorsement in Lincoln's first inaugural address. The proposal was ratified by the legislatures of Ohio

(May 13, 1861) and Maryland (January 10, 1862). Illinois lawmakers—sitting as a state constitutional convention at the

time—also approved it, but that action is of questionable validity. The amendment was considered for ratification in

several additional states including Connecticut, Kentucky, and New York but was either rejected or died in committee under

neglect as other pressing wartime issues came to preoccupy the nation's attention. The Corwin Amendment was never ratified.

January 21-23, 1861 - Northern Legislatures Pledge Support for Union. New

York legislature pledges support to the Union on January 21, followed by the legislatures of Wisconsin (January 22), Massachusetts

(January 23), and Pennsylvania (January 24).

February 4-27, 1861 - Washington Peace Conference. The Washington Peace

Conference met at Willard's Dancing Hall, adjoining Willard's Hotel in Washington, from February 4-27, 1861. The conference

was convened at the request of the Virginia legislature on January 18, but only some of the states sent representatives. Ultimately

131 members participated from the 21 states still in the Union. Present on the first day were delegates from New Hampshire,

Vermont, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Ohio,

Indiana and Iowa, 14 states. During the conference delegates arrived from Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Tennessee, Missouri,

Illinois and Kansas. The convention had invited delegates from all states, including those that had already seceded, but the

seven seceding states of the deep South boycotted. In addition Arkansas, California, Oregon, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota

did not send representatives. The meeting was primarily a forum for the upper South to express their moderate aims. The Convention

sent representatives to meet with President Buchanan. Former president John Tyler of Virginia was the presiding officer. Among

the delegates were men of distinction and leadership, including David Wilmot of Pennsylvania, David Dudley Field of New York,

Reverdy Johnson of Maryland, William C. Rives of Virginia, and Salmon P. Chase of Ohio. The conference consciously modeled

itself after the Constitutional Convention of 1787, but many of its delegates were, in striking contrast, elderly and past

their political prime. Tyler himself was seventy-one. The meeting was characterized as an "old gentlemen's convention," its

delegates as "venerable," and less politely as "fossils." Their proposals were framed as a single amendment to the Constitution

of seven sections. In its essence it is very similar to the Crittenden Compromise, although slightly different in wording

and some of the details, borrowing a bit from some of the proposals made to the Committee of Thirteen. The amendment was brought

up in the Senate on February 27, 1861, by Senator Lazarus W. Powell of Kentucky, but it was unsatisfactory to the Republicans,

who objected to it on the ostensible ground of the incompetency of the conference to prepare amendments for congressional

action, and to the southern senators, who preferred secession to any amendment without a formal acceptance by Republican votes.

The amendment was satisfactory only to the Union-loving Democrats of the Middle and Border States. On the last day of the session an effort made to substitute the conference amendment for senator

Douglas' amendment, as contained in the house resolutions, was voted down by a vote of 34 to 3. In the House various attempts

were made from February 27 until March 3 to introduce the conference amendment, but all were unsuccessful.

April 4, 1861 - Lincoln Orders Relief Ship to Ft. Sumter. Abraham Lincoln

orders a relief shipment of food to Fort Sumter; the expedition sails from New York on April 8.

April 9, 1861 - The Confederate Cabinet concurs with President Jefferson

Davis's order to General Pierre G.T. Beauregard that Fort Sumter should be reduced before the relief fleet arrives.

April 10, 1861 - Confederate Secretary of War Leroy Pope Walker orders Pierre

G.T. Beauregard to demand the evacuation of Fort Sumter, under threat of bombardment. The Sumter relief fleet begins to leave

New York harbor.

April 27, 1861 - Habeas Corpus Suspended. Abraham Lincoln authorizes the suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus in a

limited area between Washington and New York, principally Maryland, in an order issued to Winfield Scott, Commander of the Army: "You are

engaged in repressing an insurrection against the laws of the United States. If at any point on or in the vicinity of the

military line which is now used between the city of Philadelphia via Perryville, Annapolis City and Annapolis Junction you

find resistance which renders it necessary to suspend the writ of habeas corpus for the public safety, you personally or through

the officer in command at the point where resistance occurs are authorized to suspend that writ." A challenge was mounted

to Lincoln's action in ex parte Merryman (1861). On May 25, 1861, John Merryman, a Maryland resident and avowed secessionist,

was arrested and detained in Fort McHenry. In April 1861, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, then sitting on the Circuit Court

bench, found that Merryman was being held unlawfully and issued a writ of habeas corpus. General George Cadwalader, in command

of Fort McHenry, refused to obey the writ, however, on the basis that President Abraham Lincoln had suspended habeas corpus

and citing the fact that he was acting in compliance with an Executive Order. Taney cited Cadwalader for contempt of court

and then wrote an opinion about Article I, Section 9, of the Constitution, which allows suspension of habeas corpus "when

in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it." Taney argued that only Congress—not the president—had

the power of suspension. Indeed the Constitution (Article 1, Section 9) is silent on who can make the decision to suspend.

Lincoln simply ignored Taney's order. President Lincoln justified his action in a message to Congress in July 1861.The limited

suspension of habeas corpus was rescinded on February 14, 1862. Merryman was later released.

| Expansion of slavery in the United States |

|

| (Map) Expansion of slavery in the United States |

May 24, 1861 - Union Forces Occupy Alexandria, Va. At 2:00 a.m. on May 24,

1861, the day after the citizens of Virginia voted three to one to secede from the Union, 11 regiments of Union soldiers invaded

Virginia and occupied the countryside across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The few Rebel pickets in Arlington, the

town directly across the river from Washington, quickly retreated from the two Union columns that descended upon them. Confederate

Gen. Robert E. Lee's spacious estate on Arlington Heights was quickly occupied as a Union military command post. The 700 Virginia

militiamen stationed six miles downstream at Alexandria, an important port and railroad center, were warned of this invasion

in time for all but 35 of them to retreat through one end of town as Union troops rushed in the other. Two Union forces converged

on Alexandria. Col. Orlando B. Wilcox and his 1st Michigan Regiment marched down from Arlington and Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth

and his exotically dressed 11th New York Zouave Regiment arrived at the Alexandria wharf aboard three river steamers. The

Zouaves rushed ashore at daybreak and quickly secured the railroad station and telegraph office. As Ellsworth moved through

the town, he spied a large Confederate flag flying from atop an inn called the Marshall House. Ellsworth rushed into the inn

with four companions, climbed the stairs to the top, and cut down the flag. As they were going back down with the flag, innkeeper

James W. Jackson met them at the third floor landing with a double-barreled shotgun in his hands. Jackson was killed—shot

in the face, bayoneted, and pushed down the steps—but not before he pulled the trigger and killed Ellsworth. The Union

invasion was a resounding success. The 24 year old Ellsworth had been a personal friend of President Abraham Lincoln, and

his body lay in state at the White House. Ellsworth became a Union martyr, and babies, streets, and even towns were named

after him.

June 10, 1861 - Battle of Bethel Church. This was the first land battle in Virginia. Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler sent converging columns from Hampton and

Newport News against advanced Confederate outposts at Little and Big Bethel. Confederates abandoned Little Bethel and fell

back to their entrenchments behind Brick Kiln Creek, near Big Bethel Church. The Federals, under immediate command of Brig.

Gen. Ebenezer W. Pierce, pursued, attacked frontally along the road, and were repulsed. Crossing downstream, the 5th New York

Zouaves attempted to turn the Confederate left flank, but were repulsed. Unit commander Col. T. Wynthrop was killed. The Union

forces were disorganized and retired, returning to Hampton and Newport News. The Confederates suffered 1 killed, 7 wounded.

Early December, 1861 - Joint Committee On The Conduct Of The War. To monitor

both military progress and the Abraham Lincoln administration, Congress creates the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the

War. The War Committee, as it was called, was created in the aftermath of the disastrous Battle of Ball's Bluff in October

1861 and was designed to provide a check over the executive branch's management of the war. The committee was stacked with

Radical Republicans and staunch abolitionists, however, and was often biased in its approach to investigations of the Union

war effort. Senate members included Republicans Benjamin F. Wade of Ohio (Chairman) and Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, two

of the most prominent radicals in the Republican Party. Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, the only senator from a seceded state,

was the sole Democratic senator on the committee. When Johnson was appointed military governor of Tennessee in March 1862,

he was replaced by Joseph Wright, the former governor of Indiana. House members included Republicans George W. Julian of Indiana,

John Covode of Pennsylvania, and Daniel Gooch of Massachusetts. Moses Fowler Odell from Brooklyn, New York, was the sole Democratic

house member. Among other things, the War Committee investigated fraud in government war contracts, the treatment of Union

prisoners held in the South, alleged atrocities committed by Confederate troops against Union soldiers, and the Sand Creek

Massacre of Indians in Colorado. Most of the committee's energies were directed towards investigating Union defeats, particularly

those of the Army of the Potomac. Many members were bitterly critical of generals like George B. McClellan and George G. Meade,

Democrats they believed to be "soft" on slavery. The War Committee was often at odds with the Lincoln administration's handling

of the war effort, and had particular problems with the administration's military decisions. At the beginning of the war,

it was critical because the administration did not have the eradication of slavery as one of its goals. Even after the Emancipation

Proclamation, the committee still found fault with many of the administration's decisions-for instance, they did not want

any Democratic generals in the army. Members of the committee often leaked testimony to the press and contributed to the jealousy

and distrust among Union generals. Although the committee did help to uncover fraud in war contracts, the lack of military

expertise by its members often complicated the Northern war effort.

April 16, 1862 - The Battle of Dam No. 1 (Burnt Chimneys). On April 5, 1862,

during the Peninsula Campaign, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's army found its progress toward Richmond, during

the blocked by the Confederate fortifications at nearby Lee's Mill. Confederate Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder had constructed

dams and built extensive fortifications to make the sluggish Warwick River into a defensive barrier. Dam No. 1 was the midpoint

between two pre-war tide mills at Lee's Mill and Wynne's Mill. Southern soldiers expected an assault at any time. As Surgeon

James Holloway of the 18th Mississippi wrote, "why they do not attack is strange for they have a heavy force and every day's

delay only gives us the opportunity to strengthen our defenses." An attack finally came on April 16, 1862, when McClellan

ordered Brig. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith to disrupt Confederate control of Dam No. 1. On the morning of April 16, Union

artillery, including Mott's 3rd New York Battery, began shelling the Confederate earthworks. By noon it appeared as if the

Southerners had abandoned their defenses and at 3:00 p.m. Smith sent 200 men of the 3rd Vermont forward as skirmishers. The

Vermonters dashed across the Warwick River and captured the first line of rifle pits held by the 15th North Carolina. The

Federal troops, their ammunition wet and having not received reinforcements, were forced to withdraw under the stress of a

vicious counterattack by Thomas R. R. Cobb's Georgia Legion. The water "boiled with bullets" as the Vermonters recrossed "that

fatal stream." A second attempt to capture Dam No. 1 failed to reach the Confederate lines as the Confederates had reinforced

the position. The engagement resulted in 165 Federal and 145 Confederate casualties. The Battle of Dam No. 1 (also called

the Battle of Burnt Chimneys) was a missed opportunity for the Union to break the Warwick River defenses. Two Federal soldiers,

Captain Samuel E. Pingree and Musician Julian Scott, were awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism during the short, vicious

fight along "a creek with a wide dam, which drank the blood of many of our men."

March 3, 1863 - The March Conscription Act creates an impartial draft lottery.

The Bill affects male citizens aged 20 to 45, but also exempts those who pay $300 or provide a substitute. "The blood of a

poor man is as precious as that of the wealthy," poor Northerners complain. The bill caused enormous anger among the poor,

who rioted in cities across the country. In New York City, implementation of the draft sparked a three-day riot in July in

which poor whites and immigrant workers attacked the black community and lynched at least a dozen African Americans.

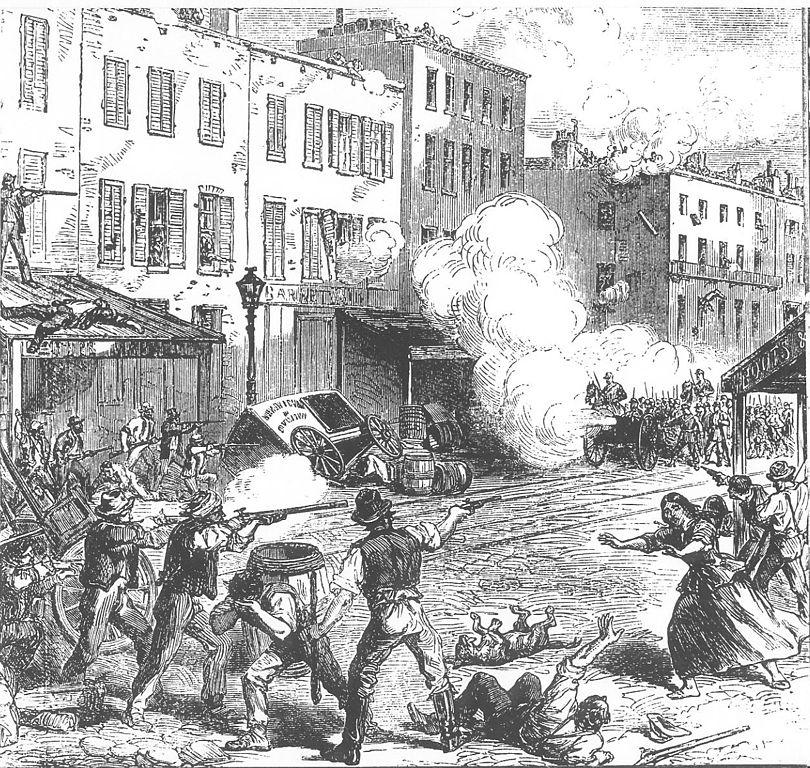

July 13-14, 1863 - Draft Riots. In response to the Conscription Act, mobs

consisting largely of poor whites and immigrants riot in Boston; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Rutland, Vermont; Wooster, Ohio;

Troy, New York; and New York City. "The nation is at this time in a state of Revolution, North, South, East, and West," wrote

the Washington Times during the often violent protests that occurred after Abraham Lincoln issued the March 3, 1863, Enrollment

Act of Conscription. Although demonstrations took place in many Northern cities, the riots that broke out in New York City

were both the most violent and the most publicized. With a large and powerful Democratic party operating in the city, a dramatic

show of dissent had been long in the making. The state's popular governor, Democrat Horatio Seymour, openly despised Lincoln

and his policies. In addition, the Enrollment Act shocked a population already tired of the two-year-old war. By the time

the names of the first draftees were drawn in New York City on July 11, reports about the carnage of Gettysburg had been published

in city papers. Lincoln's call for 300,000 more young men to fight a seemingly endless war frightened even those who supported

the Union cause. Moreover, the Enrollment Act contained several exemptions, including the payment of a "commutation fee" that

allowed wealthier and more influential citizens to buy their way out of service. Perhaps no group was more resentful of these

inequities than the Irish immigrants populating the slums of northeastern cities. Poor and more than a little prejudiced against

blacks-with whom they were both unfamiliar and forced to compete for the lowest-paying jobs-the Irish in New York objected

to fighting on their behalf. On Sunday, June 12, the names of the draftees drawn the day before by the Provost Marshall were

published in newspapers. Within hours, groups of irate citizens, many of them Irish immigrants, banded together across the

city. Eventually numbering some 50,000 people, the mob terrorized neighborhoods on the East Side of New York for three days

looting scores of stores. Blacks were the targets of most attacks on citizens; several lynchings and beatings occurred. In

addition, a black church and orphanage were burned to the ground. All in all, the mob caused more than $1.5 million of damage.

The number killed or wounded during the riot is unknown, but estimates range from two dozen to nearly 100. Eventually, Lincoln

deployed combat troops from the Federal Army of the Potomac to restore order; they remained encamped around the city for several

weeks. In the end, the draft raised only about 150,000 troops throughout the North, about three-quarters of them substitutes,

amounting to just one-fifth of the total Union force.

| New York Draft Riots in 1863 |

|

| Depiction of New York Draft Riots in 1863. The Illustrated London news, ca. 1863. |

May 18, 1864 - The Gold Hoax. The Civil War Gold Hoax was perpetrated by

two U.S. journalists to exploit the financial situation during 1864. On May 18, 1864, two New York City newspapers, the New

York World and the New York Journal of Commerce, published a story that President Abraham Lincoln had issued a proclamation

of conscription of 400,000 more men into the Union army. At the time, there were fierce battles taking place between Union

and Confederate troops in Virginia and the public took it to mean that the war was not going well for the Union. Share prices

fell on the New York Stock Exchange when investors began to buy gold, and its value increased 10%. During the day a number

of people, one of them former Union commander General George McClellan, became suspicious of the fact that the proclamation

had been published in just two newspapers, and went to the offices of the Journal to determine the source. Editors of the

paper showed then an Associated Press dispatch they had received early in the morning. Before noon, the Associated Press issued

a statement that the dispatch had not come from them, and at 12.30 p.m. the State Department in Washington DC sent a telegram

to verify that the proclamation was "an absolute forgery". By then, however, the stock market had already been affected. Further

investigation revealed that the dispatches had come through a young courier just after the night editors had gone home. The

timing had been perfect—the night foreman had had to make a decision as to whether to include the proclamation in the

next day's paper or not. Night foremen in various other newspapers had tried to verify the message, and when they found out

that not every paper had received the message, they decided to delay it pending further proof. Only foremen for the World

and Journal of Commerce had added it. President Lincoln was enraged when he heard about the case: he gave an order to close

the two papers down and had their editors arrested for suspicion of complicity. Soldiers seized the two offices and, for some

reason, the office of the Independent Telegraph Line. Lincoln eventually had the editors released. Detectives tracked down

the culprits. They found the messengers and questioned them. On May 21 they arrested Francis A. Mallison, a reporter for the

Brooklyn Eagle who informed on his city editor Joseph Howard, who was also arrested. Howard came quietly and confessed. Howard

had bought gold on margin May 17 and started the ruse because he knew that any news of a delay in the war would cause a rise

in the price of gold when investors wanted to transfer their savings elsewhere. He had forged the two AP dispatches and had

them sent to various city newspapers in an appropriate time. The next day, during the furor, he had sold his investment and

profited immensely. Howard spent only three months in prison and was released on August 22, 1864. With perfect irony, at that

time Lincoln had to issue a call for 500,000 more soldiers.

March 18, 1865 - Confederate Congress Adjoursn. The Congress of the Confederate

States of America adjourns for the last time.

March 19-21, 1865 - Battle of Bentonville. While Henry W. Slocum's advance

was stalled at Averasborough by William J. Hardee's troops, the right wing of William T. Sherman's army under command of Maj.

Gen. Oliver Otis Howard marched toward Goldsborough. On March 19, Slocum encountered the entrenched Confederates of Gen. Joseph

E. Johnston who had concentrated to meet his advance at Bentonville. Late afternoon, Johnston attacked, crushing the line

of the XIV Corps. Only strong counterattacks and desperate fighting south of the Goldsborough Road blunted the Confederate

offensive. Elements of the XX Corps were thrown into the action as they arrived on the field. Five Confederate attacks failed

to dislodge the Federal defenders and darkness ended the first day's fighting. During the night, Johnston contracted his line

into a "V" to protect his flanks with Mill Creek to his rear. On March 20, Slocum was heavily reinforced, but fighting was

sporadic. Sherman was inclined to let Johnston retreat. On the 21st, however, Johnston remained in position while he removed

his wounded. Skirmishing heated up along the entire front. In the afternoon, Maj. Gen. Joseph Mower led his Union division

along a narrow trace that carried it across Mill Creek into Johnston's rear. Confederate counterattacks stopped Mower's advance,

saving the army's only line of communication and retreat. Mower withdrew, ending fighting for the day. During the night, Johnston

retreated across the bridge at Bentonville. Union forces pursued at first light, driving back Joseph Wheeler's rearguard and

saving the bridge. Federal pursuit was halted at Hannah's Creek after a severe skirmish. Sherman, after regrouping at Goldsborough,

pursued Johnston toward Raleigh. On April 18, Johnston signed an armistice with Sherman at the Bennett House, and on April

26, formally surrendered his army.

March 22-April 2, 1865 - Raid on Selma. Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson, commanding

three divisions of Union cavalry, about 13,500 men, led his men south from Gravelly Springs, Alabama, on March 22, 1865. Opposed

by Confederate Lt. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest, Wilson skillfully continued his march and eventually defeated him in a running

battle at Ebenezer Church, on April 1. Continuing towards Selma, Wilson split his command into three columns. Although Selma

was well-defended, the Union columns broke through the defenses at separate points forcing the Confederates to surrender the

city, although many of the officers and men, including Forrest and Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, escaped. Selma demonstrated that

even Forrest, whom some had considered invincible, could not stop the unrelenting Union movements deep into the Southern Heartland.

March 25, 1865 - Battle of Fort Stedman. In a last-gasp offensive, Gen.

Robert E. Lee amassed nearly half of his army in an attempt to break through Ulysses S. Grant's Petersburg defenses and threaten

his supply depot at City Point. Lee ordered General John B. Gordon to formulate a plan that would allow the Confederate Army

to pull out of Petersburg and perhaps give it the opportunity to link up with the Confederate army in North Carolina under

General Joseph E. Johnston. Gordon's idea was a surprise attack on the Union lines to force Ulysses S. Grant to shorten his

lines or even set his lines back. He hoped that the breakthrough would lead to the main Union supply base of City Point, ten

miles northeast. In detail, Gordon planned a pre-dawn assault on Fort Stedman, one of the fortifications marking the Union

lines that encircled Petersburg. It was one of the closest spots on the line, there were fewer wooden chevaux de frise obstructions,

and a supply depot on the U.S. Military Railroad was less than a mile behind it. Directly after capturing the fort, Confederate

soldiers would move north and south along the Union lines to clear the neighboring fortifications to make way for the main

attack. The assault force was Gordon's Second Corps of 7,500 men, backed by Robert Ransom's North Carolina brigade and William

Wallace's South Carolina brigade, in all about 10,000 men, with 5,000 in reserve. The attack started at 4:00 a.m. On a signal,

lead parties of sharpshooters and engineers who masqueraded as deserting soldiers headed out to overwhelm Union pickets and

to remove wooden defenses that would have obstructed the infantry advance. It was a complete surprise as they captured Fort

Stedman and the batteries (designated Batteries X and XI) just to the north and south of it. Forces under sector commander

Brig. Gen. Napolean McLaughlen, many of them heavy artillery troops serving as infantry, used canister fire against the attackers,

but were unable to organize an effective defense. They attempted to fire mortars from Battery XII onto Stedman, but to no

avail. McLaughlen arrived at Stedman without knowing it had changed hands and was forced to surrender his sword to Gordon.

The Confederates captured nearly 1,000 prisoners. Gordon's next objective was to widen his breakthrough by capturing Fort

McGilvery to the north, and Fort Haskell to the south of Stedman. The lead attackers reached Harrison's Creek along the Prince

George Court House Road, but were unable to widen their breakthrough past the neighboring forts. (Unfortunately for the defenders

of Haskell, Union batteries in other forts assumed it had fallen and shelled it with friendly fire.) Reserve forces waited

for the word to launch the main attack in the direction of City Point. But the Union was not willing to retreat. Union General

John Hartranft, commander of the IX Corps Reserve Division (a unit made up of six newly recruited Pennsylvania regiments),

gathered his troops for a counterattack. With artillery support from up and down the Union line, Hartranft brought the Confederates

under a killing crossfire, and counterattacks led by Maj. Gens. John G. Parke and Hartranft contained the breakthrough, cut

off, and captured more than 1,900 of the attackers. Gordon, who was in Fort Stedman, realized the plan had failed when his

lead men started returning and reported remarkable Union resistance. By 7:30 a.m. Union forces had sealed the breach and their

artillery was heavily bombarding the fort. A coordinated attack started before 8.00 a.m. and Hartranft managed to retake the

fort and restored the initial Union line. The retreating Confederates came under Union crossfire, suffering heavy casualties.

Their attack had failed. The attack on Fort Stedman turned out to be a four-hour action with no impact on the Union lines.

In fact the Confederate Army was forced to set back its own lines, as the Union attacked further down the front line. To give

Gordon's attack enough strength to be successful, Lee had weakened his own left flank. There, near Fort Fisher, elements of

the II and VI Corps assaulted and captured the entrenched picket lines in their respective fronts, which had been weakened

for the assault on Fort Stedman. This was a devastating blow for Lee's army, setting up the Confederate defeat at Five Forks

on April 1 and the fall of Petersburg on April 2-3. Lee's army suffered heavy casualties during the battle of Fort Stedman—about

2,900, including 1,000 captured in the Union counterattack. But more seriously, the Confederate positions were weakened. After

the battle, Lee's defeat was only a matter of time. His final opportunity to break the Union lines and regain the momentum

was gone. The Battle of Fort Stedman was the final episode of the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign. Immediately following was

the Appomattox Campaign, including the Battle of Five Forks and the final surrender of Lee's army on April 9, 1865.

April 1, 1865 - Battle of Five Forks. Gen. Robert E. Lee orders George E.

Pickett to hold the vital crossroads of Five Forks, southwest of Petersburg, Virginia, at all hazard. ("Five Forks" referred

to the intersection of the White Oak Road, Scott's Road, Ford's (or Church) Road, and the Dinwiddie Court House Road.) Lee's

dispatch stated: "Hold Five Forks at all hazards. Protect road to Ford's Depot and prevent Union forces from striking the

Southside Railroad. Regret exceedingly your forces' withdrawal, and your inability to hold the advantage you had gained".

Pickett's troops built a log and dirt defensive line about 1.75 miles long, guarding the two flanks with cavalry. Unfortunately

for the Union plans for attack, faulty maps and intelligence misunderstood where these flanks actually were. On April 1, while

Philip H. Sheridan's cavalry pinned the Confederate force in position at about 4 p.m., Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren attacked

and overwhelmed the Confederate left flank, taking many prisoners. Sheridan personally directed the attack, which extended

Lee's Petersburg lines to the breaking point. Pickett's unfortunate military career suffered another humiliation—he

was two miles away from his troops at the time of the attack, enjoying a shad bake with some other officers. By the time he

returned to the battlefield, it was too late. Loss of Five Forks threatened Lee's last supply line, the South Side Railroad.

The next morning, Lee informed President Jefferson Davis that Petersburg and Richmond must be evacuated. Union general Frederick

Winthrop was killed and Willie Pegram, beloved Confederate artillery officer, was mortally wounded. Sheridan was dissatisfied

with the performance of the V Corps in the approach to Five Forks and he relieved Warren of his command.

April 2-3, 1865 - Capture of Richmond. After the victory at Five Forks,

Ulysses S. Grant orders a general advance against Robert E. Lee's lines at Petersburg. Horatio G. Wright's VI Corps, spearheaded

by the Vermont Brigade, made a decisive breakthrough along the Boydton Plank Road line. John Gibbon's XXIV Corps overran Fort

Gregg after a heroic Confederate defense. John G. Parke's IX Corps overran the eastern trenches but met with stiff resistance

under John B. Gordon. General A.P. Hill was killed while trying to restore the broken Confederate line along the Boydton Plank

Road. Hill had earlier vowed that he would never leave the Petersburg defenses. Lee decides to evacuate Petersburg. President

Jefferson Davis, his family and government officials, are forced to flee from Richmond. Fires and looting break out. The next

day, Union troops enter and raise the Stars and Stripes. One resident, Mary Fontaine, wrote, "I saw them unfurl a tiny flag,

and I sank on my knees, and the bitter, bitter tears came in a torrent." As the Federals rode in, another wrote that the city's

black residents were "completely crazed, they danced and shouted, men hugged each other, and women kissed." Among the first

forces into the capital were black troopers from the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry, and the next day President Abraham Lincoln

visited the city. For the residents of Richmond, these were symbols of a world turned upside down. It was, one reporter noted,

"too awful to remember, if it were possible to be erased, but that cannot be."

April 4, 1865 - Lincoln Visits Richmond. Abraham Lincoln had been in the

area or Richmond for nearly two weeks. He left Washington at the invitation of general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant to visit

Grant's headquarters at City Point, near the lines at Petersburg south of Richmond. The trip was exhilarating for the exhausted

president. Worn out by four years of war and stifled by the pressures of Washington, Lincoln enjoyed himself immensely. He

conferred with Grant and General William T. Sherman, who took a break from his campaign in North Carolina. He visited soldiers,

and even picked up an axe to chop logs in front of the troops. He stayed at City Point, sensing that the final push was near.

Grant's forces overran the Petersburg line on April 2, and the Confederate government fled the capital later that day. Union

forces occupied Richmond on April 3, and Lincoln sailed up the James River to see the spoils of war. His ship could not pass

some obstructions that had been placed in the river by the Confederates so 12 soldiers rowed him to shore. He landed without

fanfare but was soon recognized by some black workmen who ran to him and bowed. The modest Lincoln told them: "Don't kneel

to me. You must kneel to God only and thank him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy." Lincoln, accompanied by a small

group of soldiers and a growing entourage of freed slaves, walked to the Confederate White House and sat in President Jefferson

Davis's chair. He walked to the Virginia statehouse and saw the chambers of the Confederate Congress. Lincoln even visited

Libby Prison, where thousands of Union officers were held during the war. Lincoln remained a few more days in hopes that Robert

E. Lee's army would surrender, but on April 8 he headed back to Washington.

April 1-9, 1865 - The Appomattox Campaign. The Confederate retreat began

on April 1 southwestward as Robert E. Lee sought to use the still-operational Richmond & Danville Railroad. At its western

terminus at Danville he would unite with Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's army, which was retiring up through North Carolina. Taking

maximum advantage of Danville's hilly terrain, the two Southern forces would make a determined stand against the converging

armies of Ulysses S. Grant and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. But Grant moved too fast for the plan to materialize, and Lee

waited 24 hours in vain at Amelia Court House for trains to arrive with badly needed supplies. Federal cavalry, meanwhile,

sped forward and cut the Richmond & Danville at Jetersville. Lee had to abandon the railroad, and his army stumbled across

rolling country in an effort to reach Lynchburg, another supply base that could be defended. Union horsemen seized the vital

rail junction at Burkeville as Federal infantry continued to dog the Confederates. On April 6 almost one-fourth of Lee's army

was trapped and captured at Sayler's Creek. Lee, at Farmville. Most surrendered, including Confederate generals Richard S.

Ewell, Barton, Simms, Joseph B. Kershaw, Custis Lee, Dubose, Eppa Hunton, and Corse. This action was considered the death

knell of the Confederate army. Upon seeing the survivors streaming along the road, Lee exclaimed "My God, has the army dissolved?"

Lee led his remaining 30,000 men in a north-by-west arc across the Appomattox River and toward Lynchburg. In the meantime,

Grant, with four times as many men, sent Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan's cavalry and most of two infantry corps on a hard,

due-west march from Farmville to Appomattox Station. Reaching the railroad first the Federals blocked Lee's only line of advance.

April 9, 1865 - Surrender at Appomattox. Early on April 9, the remnants

of John B. Gordon's corps and Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry formed a line of battle at Appomattox Court House. Gen. Robert E. Lee

determined to make one last attempt to escape the closing Union pincers and reach his supplies at Lynchburg. At dawn the Confederates

advanced, initially gaining ground against Philip H. Sheridan's cavalry. The arrival of Union infantry, however, stopped the

advance in its tracks. Lee's army was now surrounded on three sides. Lee's options were gone. That afternoon, Palm Sunday,

Lee met Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in the front parlor of Wilmer McLean's home to discuss peace terms. After

agreeing terms, Lee surrendered his army. The actual surrender of the Confederate Army occurred April 12, an overcast Wednesday.

As Southern troops marched past silent lines of Federals, a Union general noted "an awed stillness, and breath-holding, as

if it were the passing of the dead." Grant issued a brief statement: "The war is over; the rebels are our countrymen again

and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to abstain from all demonstrations in the field." Grant allows Rebel

officers to keep their sidearms and permits soldiers to keep horses and mules. Lee tells his troops: "After four years of

arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming

numbers and resources".

April 10, 1865 - Celebrations break out in Washington.

| The President has been assassinated |

|

| The Last Photo of Abraham Lincoln |

April 14, 1865 - Assassination of Lincoln. The Stars and Stripes is ceremoniously

raised over Fort Sumter. That night, Abraham Lincoln and his wife Mary see the play "Our American Cousin" at Ford's Theater.

At 10:13 p.m., during the third act of the play, John Wilkes Booth shoots the president in the head. As he leaps to the stage

(breaking a shinbone), Booth shouts, Sic Semper Tyrannis (Thus Always to Tyrants). Doctors attend to the president in the

theater then move him to a house across the street. He never regains consciousness. Abraham Lincoln died the next morning

(April 15) at 7:22 a.m. in the Petersen Boarding House. He was 56 years old. Vice President Andrew Johnson assumes the presidency.

Secretary of State William H. Seward was stabbed in his Washington home on April 14, 1865, the same night President Lincoln

was shot in the Ford Theater. The attacker, Louis Powell, a co-conspirator with Booth, injured five people in the nighttime

action. Seward recovered from his injuries and continued to serve as Secretary of State for President Andrew Johnson.

April 18, 1865 - Surrender of Johnston. Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston

in North Carolina succeeds in delaying the advance of General William T. Sherman at Bentonville in March. But lack of men

and supplies forced Johnston to order continued withdrawal, and he surrendered to Sherman at Durham Station, N.C., on April

26.

April 26, 1865 - John Wilkes Booth Killed. Union cavalry corner John Wilkes

Booth in a tobacco barn in Bowling Green, Virginia. Cavalryman Boston Corbett shoots the assassin dead.

April 27, 1865 - Sinking of the Sultana. The steamboat Sultana, carrying

2,300 passengers, explodes and sinks in the Mississippi River, killing 1,700. Most were Union survivors of the Andersonville

Prison.

May 4, 1865 - Burial of Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln is laid to rest in Oak

Ridge Cemetery, outside Springfield, Illinois.

May 4, 1865 - Surrender of Taylor. Confederate General Richard Taylor, commanding

all Confederate forces in Alabama, Mississippi, and eastern Louisiana, surrenders his forces to Union General Edward Canby

at Citronelle, Alabama.

May 5, 1865 - First Train Robbery in U.S. In North Bend, Ohio (a suburb

of Cincinnati), the first train robbery in the United States takes place. About a dozen men tore up tracks to derail an Ohio

& Mississippi train that had departed from Cincinnati. (Some reports identify the train as belonging to the Union Pacific

Railroad). More than 100 passengers were robbed at gunpoint of cash and jewelry. The robbers then blew open safes of the Adams

Express Co. that were said to contain thousands of dollars in U.S. bonds. The robbers fled across the Ohio River into Kentucky.

Lawrenceburg, Indiana officials were notified by telegraph of the robbery and in turn notified military authorities. Troops

were sent to hunt down the robbers. The outlaws were traced through Verona, Kentucky, but were never captured.

May 10, 1865 - Capture of Jefferson Davis. Jefferson Davis, president of

the Confederacy, fleeing to Georgia, is captured on May 10 and imprisoned at Fortress Monroe, on the coast of Virginia, on

May 19. Davis was indicted for treason in May 1866, but in 1867 he was released on bail which was posted by prominent citizens

of both northern and southern states, including Horace Greeley and Cornelius Vanderbilt who had become convinced he was being

treated unfairly. He visited Canada, and sailed for New Orleans, Louisiana, via Havana, Cuba. In 1868, he traveled to Europe.

That December, the court rejected a motion to nullify the indictment, but the prosecution dropped the case in February of

1869.

May 12-13, 1865 - Battle of Palmito Ranch was fought on May 12-May 13, 1865,

and in the kaleidoscope of events following the surrender of Robert E. Lee's army, was nearly ignored. It was the last major

clash of arms in the war. Early in 1865, both sides in Texas agreed to a gentlemen's agreement that there was no point to

further hostilities. Why the needless battle even happened remains something of a mystery—perhaps Union Colonel Theodore

H. Barrett had political aspirations (he certainly had little military experience). Barrett instructed Lieutenant Colonel

David Branson to attack the rebel encampment at Brazos Santiago Depot near Fort Brown outside Brownsville. By that time, most

Union troops had pulled out from Texas for campaigns in the east. The Confederates were concerned to protect what ports they

had for cotton sales to Europe, as well as importation of supplies. Mexicans tended to side with the Confederates due to a

lucrative smuggling trade. Union forces marched upriver from Brazos Santiago to attack the Confederate encampment, and were

at first successful but were then driven back by a relief force. The next day, the Union attacked again, again to initial

success and later failure. Ultimately, the Union retreated to the coast. There were 118 Union casualties. Confederate casualites

were "a few dozen" wounded, none killed. Nothing was really gained on either side; like the war's first big battle (First

Bull Run to the Union, First Manassas to the Confederates), it is recorded as a Confederate victory. It is worth noting that

private John J. Williams of the 34th Indiana Volunteer Infantry was the last man killed at the Battle at Palmito Ranch, and

probably the last of the war. Fighting were white, African, Hispanic and native troops. Reports of shots from the Mexican

side are unverified, though many witnesses reported firing from the Mexican shore.

May 23-24, 1865 - Grand Review in Washington, D.C. Over a two-day period

in Washington, D.C., the immense, exultant victory parade of the Union's main fighting forces in many ways brought the Civil

War to its conclusion. The parade's first day was devoted to George G. Meade's force, which, as the capital's defending army,

was a crowd favorite. May 23 was a clear, brilliantly sunny day. Starting from Capitol Hill, the Army of the Potomac marched

down Pennsylvania Avenue before virtually the entire population of Washington, a throng of thousands cheering and singing

favorite Union marching songs. At the reviewing stand in front of the White House were President Andrew Johnson, General-in-Chief

Ulysses S. Grant, and top government officials. Leading the day's march, General Meade dismounted in front of the stand and

joined the dignitaries to watch the parade. His army made an awesome sight: a force of 80,000 infantrymen marching 12 across

with impeccable precision, along with hundreds of pieces of artillery and a seven-mile line of cavalrymen that alone took

an hour to pass. One already famous cavalry officer, George Armstrong Custer, gained the most attention that day-either by

design or because his horse was spooked when he temporarily lost control of his mount, causing much excitement as he rode

by the reviewing stand twice. The next day was William T. Sherman's turn. Beginning its final march at 9 a.m. on another beautiful

day, his 65,000-man army passed in review for six hours, with less precision, certainly, than Meade's forces, but with a bravado

that thrilled the crowd. Along with the lean, tattered, and sunburnt troops was the huge entourage that had followed Sherman's

on his march to the sea: medical workers, laborers, black families who fled from slavery, the famous "bummers" who scavenged

for the army's supplies, and a menagerie of livestock gleaned from the Carolina and Georgia farms. Riding in front of his

conquering force, Sherman later called the experience "the happiest and most satisfactory moment of my life." For the thousands

of soldiers participating in both days of the parade, it was one of their final military duties. Within a week of the Grand

Review, the Union's two main armies were both disbanded.

May 26, 1865 - Surrender of Kirby Smith. General Kirby Smith, with 43,000

soldiers, surrenders to Gen. Edward Canby in Shreveport, Louisiana.

May 29, 1865 - Amnesty Proclamation. Andrew Johnson presents his "restoration"

plan, which is at odds with Congress' reconstruction plan. He also announces a general

pardon for everyone involved in the "rebellion," except for a few Confederate leaders.

June 23, 1865 - Surrender of Stand Watie. At Fort Towson in the Choctaw

Nations' area of Oklahoma Territory, Brig. Gen. Stand Watie surrendered the last significant rebel army, becoming the last

Confederate general in the field to surrender.

See also

Sources: National Park

Service; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; National Archives; Library of Congress; US Census Bureau; The

Union Army (1908); Fox, William F. Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (1889); Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of

the War of the Rebellion (1908); Hardesty, Jesse. Killed and died of wounds in the Union army during the Civil War (1915):

Wright-Eley Co.; United States Army Center of Military History; publications.usa.gov.

|

|

|