|

Civil War Battle of Five Forks

An Archaeological Overview and Assessment of the Five Forks Battle:

Petersburg National Battlefield,

Virginia

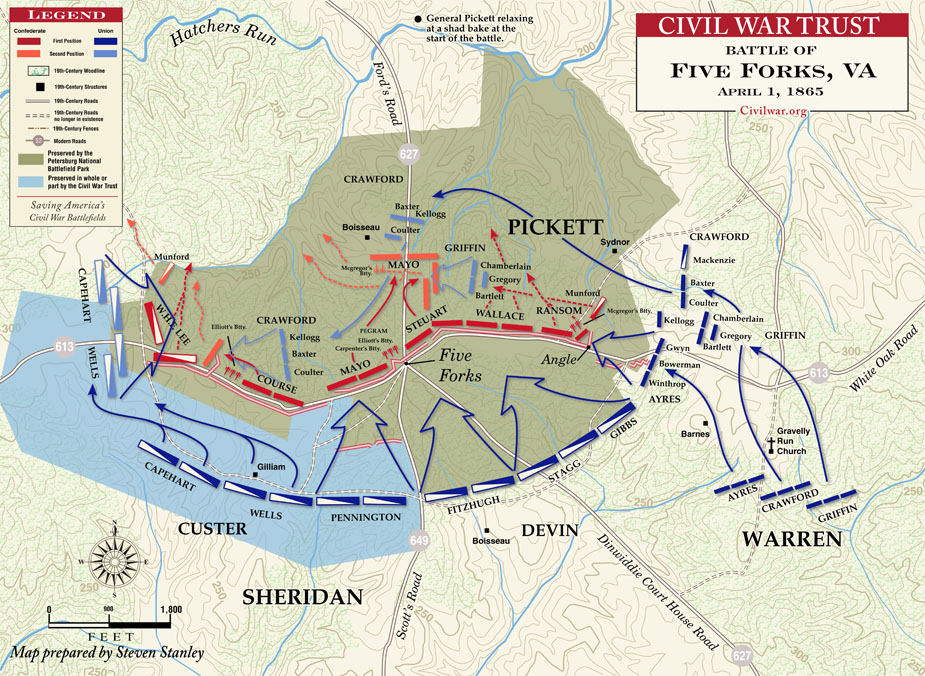

| Battle of Five Forks Map |

|

| Virginia Civil War Five Forks Battlefield Map |

Summary and Observations

The Five Forks Unit was added to Petersburg National Battlefield to

preserve and interpret the site of the April 1, 1865, battle that led to the end of the siege at Petersburg and the surrender

of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. However, the acreage within the boundaries of

the Five Forks Unit witnessed thousands of years of prehistoric occupation and lay within various tobacco plantations for

a least a century prior to the battle. The physical evidence of these cultural occupations may be found within the unit

at present.

As discussed in Chapter Three, no prehistoric sites have been formally recorded within the Five Fork Unit,

although six projectile points suggesting later Archaic and Middle Woodland occupations were collected from unknown locations.

Upland and upland spur landforms above small tributary streams and stream confluences were commonly occupied during Middle

and Late Archaic times (Mouer et al. 1985) and these landforms near Five Forks were probably so utilized. The presence

of Paleoindian artifacts should be recognized as a possibility given the proximity of the Williamson site.

Historic occupation in the Five Forks vicinity may be traced at least back to the mid-eighteenth century.

The emergence of land tax records in the period immediately following independence from Great Britain revealed the presence

of plantations associated with family names that remained familiar ones on the mid-nineteenth century landscape. Others, such

as the Fraser and Thweatt families, had ceased to own lands in the area by the time of the Civil War.

The plantation of "Burnt Quarter" encompassed lands surrounding the Five Forks and was at the time of the

Civil War one of the largest estates in Dinwiddie County. The plantation represented an example of descent through the female

lineage, passing from the Colemans to the Goodwyns and ultimately to the Gilliam family. Much of the land that currently forms

the Five Forks Unit was purchased from a descendant of the Civil War owner of "Burnt Quarter." The house and surrounding farm

lie south of the boundary of the park, although an easement has been granted to the National Park Service. The house represents

the sole surviving dwelling dating prior to the Civil War in the immediate vicinity of Five Forks and as such is of importance

both historically and architecturally. Family portraits that were slashed and damaged by Union cavalry during the battle

of Five Forks still hang upon the walls of the house, presenting dramatic and timeless images concerning the impact of warfare

upon the domestic scene.

The Sydnor family owned lands to the north of "Burnt Quarter" by the late eighteenth century. The elder

John Sydnor may have originally occupied the farm west of Church Road that was later attributed to Benjamin Boisseau or Charles

Young. Sydnor sold a farm on White Oak Creek to Benjamin Boisseau in 1845; Charles Young and his brothers obtained in 1849

a farm on Hatcher's Run with all the buildings Sydnor possessed at the time of his death. This latter property would seem

to be dwelling site that falls within the boundary of the park west of Route 627 or historic Church Road. The nature of the

owner/occupant structure at the time of the Civil War remains uncertain, but it seems likely that Boisseau leased the property

from the Youngs who lived elsewhere in the county. The dwelling and associated structures are no longer standing. The

former agricultural fields have been replanted with pine trees; the dwelling site is marked by large oak trees, boulders,

and a depression that probably represents the remains of a partially-filled cellar.

The "Sydnor" house that stood north of White Oak Road on most mid-nineteenth century maps was associated

with the younger John Sydnor. His father (the elder John) had purchased most of the land for this farm from heirs of deceased

members of the Thweatt family during the period 1838-1841 and gave it to his son, although the younger John supplemented his

holdings with an additional purchase from a Thweatt heir. The younger John died during the Civil War and the farm was

owned and probably occupied by his son Robert Louis, who was listed as a tenant on the 1860 Federal Census. Other tenants,

John Harmon and the free black resident Robert Amprey, evidently rented portions of the farm in 1860, but maps indicated their

dwellings lay northeast of the current park boundaries. The Sydnor dwelling, which was probably constructed by a member of

the Thweatt family in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, is no longer standing. The site lies upon an

upland spur between two tributaries of Hatcher's Run, in an area that was owned by a timber company prior to acquisition by

the Park Service.

The "Chimneys" that appeared on most mid-nineteenth century maps to the northeast of the Sydnor farm reflect

lands acquired by the younger John Sydnor in 1856. The buildings, which were listed as burned in the 1851 land tax, had

been constructed by the Fraser family during the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, and may have been enhanced by

John Fraser in 1821. The site would therefore reflect at least 50 years of occupancy by the Frasers and subsequent owner

such as Benjamin Smithey, but Sydnor probably purchased the farm for the land. Chris Calkins retrieved a wrought iron

strap hinge from the surface of the site in the early 1990s.

The abandoned frame farm dwelling that currently stands in the midst of an open field east of Route 627

(Church Road) was constructed between 1865 and 1880. An associated cemetery is located in a clump of trees surrounded

by the field to the east of the dwelling. Another unoccupied frame dwelling that postdates 1880 stands south of the

Five Forks junction, while a concrete block structure on the northeast corner of the junction has been occupied by the Park

Service as a visitor reception station.

Earthworks created prior to the battle of Five Forks in April 1865 were limited in size and extent at the

outset and have not fared well with the passage of time. The Confederate infantry constructed a nearly continuous line

of earthworks from the Gilliam farm eastward along the White Oak Road to the Sydnor farm. The works on the Gilliam farm

lay south of White Oak Road but were placed on the north side of the road near the entrance lane to "Burnt Quarter." The

eastern end of the line on the Sydnor farm was "refused," or bent perpendicularly to White Oak Road. A series of traverses

were indicated on contemporary maps, in addition to a small artillery redoubt behind the refused portion of the line, which

was described as the "Return" or "Angle." A series of isolated rifle pits extended east of the Angle along White Oak Road.

A limited line of Union earthworks was constructed perpendicular to Scott's Road south the forks.

Sections of the Confederate works along White Oak Road on the Gilliam and former Sydnor farms survive as

low, continuous mounds of earth, but other portions have been plowed down in agricultural fields or leveled during road maintenance

activities. Road and drainage ditch construction have deposited modern earthen berms that may be mistaken for Confederate

earthworks, particularly east of the forks. The actual earthworks, where they survive, are generally further from the

road within the tree line. The portion of the line known as the Angle is better preserved, with the earthen traverses still

visible. The northern end of the Angle was obliterated during timber removal activities prior to creation of the park.

Quantities of military artifacts such as bullets and accouterments were obviously deposited during the battle,

but many of these have been removed by souvenir hunters using metal detectors during the decades prior to creation of the

park. Chris Calkins has recorded anecdotal accounts such as one by a collector who found a stacked pile of unexploded

artillery shells buried northwest of the forks, in the area occupied by a Confederate artillery battery commanded by Colonel

William Pegram, who was killed in the battle.

An assessment of the archaeological potential within the Five Forks Unit inevitably must consider the larger

question of landscape. As indicated in the introductory chapter of this study, landscape is considered a multifaceted concern,

with definitions applied to these various facets that may not be commonly held ones. A major issue related to Five Forks is

the extent to which the current landscape may be considered "historic" or reflective of the landscape at the time of the battle

in April 1865.

Four different facets of landscape were discussed in the introductory chapter: historic, memorial, conceptual,

and modern. A considerable portion of this report has been devoted to examining the physical landscape between 1865 and 1880,

an examination that was aided immeasurably by the maps and documents generated by the Warren court of inquiry (1883) and the

Calkins report (1990). It is difficult to imagine a Civil War field of engagement, particularly in the Petersburg area,

that was more well documented than Five Forks. In sum, it is possible to recreate many aspects of the landscape in April 1865.

The landscape continued to be shaped and utilized by farmers and persons with other economic foci during

the late nineteenth century and for much of the twentieth century. Dwellings and farm buildings that had been built prior

to the battle were removed, while houses were constructed where none had stood previously. Creation of a national park unit

at Five Forks was authorized by Congress in 1962 but the area remained in private hands for nearly three more decades. Once

a parcel of 930 acres had been purchased from the owners of "Burnt Quarter" by the Mellon Foundation and the Conservation

Fund in 1989 and these lands were donated to the National Park Service in 1990, this continued change in the modern landscape

ceased and a memorial landscape emerged.

We tend to think of a memorial military landscape as one that contains manicured lawns, ornamental trees,

and monuments erected by or in memory of army veterans, but it is argued here that acquisition of the land by the National

Park Service or any other preservation group for the stated purpose of commemorating a specific past event represents a conscious

alteration of the course of cultural process. As such, the modern landscape around Five Forks is also a memorial landscape. The

landscape within the easement of 435 acres remains under active use as farmland by the owners of "Burnt Quarter" and as such

is not fully subject to this conscious alteration of cultural process, although the Park Service is able through the easement

to influence the actions that occur on this acreage.

| Battle of Five Forks Map |

|

| Civil War Five Forks Battlefield Map |

The National Park Service held a workshop at Petersburg National Battlefield in December 1991 to discuss

the purpose, significance, and management objectives for the various components within the park. The section relating

to management objectives for Five Forks included the following statements (NPS 1991:4): Landscape-

To re-establish and manage the Five Forks Unit as it appeared in 1865, as a remnant of the battlefield landscape, and to help

the visitor understand and appreciate the climatic battle of the Siege of Petersburg.

Cultural Resources- To preserve and maintain the integrity of the road(s) alignment, earthworks, and archaeological

ruins as important elements of the strategic defensive positions of the Confederate forces.

As mentioned above, the current distribution of fields within the Five Forks Unit roughly approximates those

present during the Civil War in quantity but not location. Indeed, only within the "Burnt Quarter" easement do 1865

fields remain cleared and under cultivation at present. Historical accounts recorded in the Warren court of inquiry proceedings

indicated that cotton was grown in Gilliam field adjacent to the forks, and that field, which lies west of the entrance road

to "Burnt Quarter," was planted in cotton in the fall of 1996. The former Boisseau/Young and Sydnor fields north of White

Oak Road are presently overgrown, and the field that currently surrounds the post-Civil War "Shanty" was much smaller in 1865.

The historical documentation is sufficiently detailed to permit one to reestablish the field and forest

boundaries to their 1865 configurations. It would be necessary to replant fields cleared after the Civil War and to clear

those older fields that have been abandoned and become overgrown with small evergreens. It should be recognized that

the initial effort of clearing and replanting, although considerable, would represent only the beginning of the program. Recreation

of the 1865 vegetation patterns is one issue, the maintenance of those patterns is another. The most obvious means of maintaining

those cleared fields and woods boundaries would be through agricultural leases, if such leases are feasible in the present-day

economy of Dinwiddie County. Further, it would be important to exercise rigid control over the types of crops grown to

ensure that they conformed to historic uses, while realizing the necessity for crop rotation and the consequent need to periodically

plant crops that were not cultivated in a given field in the spring of 1865. The treatment of field boundaries would be a

concern in most cases, since historic maps only provide detailed depictions of fence types for "Burnt Quarter."

The architectural environment has changed greatly since the mid-nineteenth century. The only surviving

farm dwelling is the Gilliam house of "Burnt Quarter," which remains in private ownership and is not visible from White Oak

Road due to a slight rise in topography south of the road. As noted in Chapter Four, most of the farm dwellings were visually

isolated from each other. The disappearance of the Boisseau/Young and Sydnor dwellings has removed important landmarks

from the battlefield. Cleared fields would thus appear empty today when in fact they surrounded small clusters of buildings

in the mid-nineteenth century.

The existence of post-Civil War structures at Five Forks has been a source of concern and debate among various

preservation groups from the creation of the park unit. Two post-Civil War dwellings currently stand, the "Shanty" constructed

between 1865 and 1880 east of Church Road and the late nineteenth-early twentieth century structure standing immediately south

of the forks. A third structure at the northeast corner of the forks probably dates to the mid-twentieth century and

currently serves as a visitor contact station for the Park Service. The frame dwellings are elements of the twentieth-century

landscape but are currently abandoned and deteriorating. This writer has no objection to the removal of these post-Civil

War buildings, including the visitor contact station, provided the frame dwellings are well documented with photographs and

drawings. It is recognized, however, that others hold a different viewpoint. Removal of the "Shanty" would still

leave the cemetery on the landscape, in this instance divorced from the associated dwelling whose occupants created the cemetery

in the first place.

The desire of the National Park Service to recreate as much of the mid-nineteenth century landscape as possible

to enhance the visitors' ability to understand the events than occurred on April 1, 1865, is an admirable one. If the opportunity

exists anywhere within Petersburg National Battlefield to restore a large portion of the battle landscape, it exists at Five

Forks. Strategic and tactical decisions were conditioned to a substantial degree by topography and ground cover and the restoration

of 1865 vegetation patterns would permit visitors to gain a greater appreciation of surface topography and tactical movements.

It should be recognized, however, that the landscape that emerges would be a memorial one that approximates the historical

landscape only in certain dimensions.

A restoration of vegetation patterns is possible, although will undoubtedly be difficult to maintain. It

may be possible to plant and cultivate crops such as tobacco, corn, wheat, and oats that were planted in the Five Forks vicinity

during the mid-nineteenth century. However, the discussion of landscape in Chapter Four indicated that agricultural practices

were often intense, particularly on the smaller farms, and were clearly dependent upon the economic and social institution

of slavery. A comprehension of the agricultural environment of necessity involves much more than consideration of crops to

be planted in specific fields. The architectural landscape is essentially gone and cannot be recreated. These observations

should not be interpreted as arguments in opposition to the restoration of vegetation patterns, but as comments directing

attention to the opinion that the resulting landscape will be a memorial to historical patterns and not a full recreation

of those patterns.

These various concepts of landscape provided the theoretical framework that guided the research for the

overview and assessment. Seven research questions or issues served as the methodological foci for this study (Shackel

1997:7):

describe the area's environmental and cultural history;

list, describe, and evaluate known

archaeological resources;

describe the potential for as-yet-unidentified archaeological resources;

describe

and evaluate past research in the area or region;

outline relevant research topics;

determine the

requirements for additional archaeological research;

provide recommendations for future research.

Data presented previously in this report and summarized in this chapter have addressed the first four issues.

Attention will now be directed to the final three questions.

The prehistoric sites that probably exist within the boundaries of the Five Forks Unit would permit research

to focus upon hunter-gatherer adaptations during the later Archaic and Woodland periods, with the possibility of earlier occupation

during the Paleoindian period. An archaeological excavation survey guided by a stratified sampling survey that focused

upon upland spurs above stream confluences would serve to investigate the spatial dimensions of the prehistoric landscape

within the unit. Should cultivation be resumed within currently overgrown areas, it will be possible to examine the

plowed fields for both prehistoric and historic artifacts.

The historic farmstead sites that are located within the unit fall into three categories:

late eighteenth century to mid-nineteenth century (the "Chimneys");

late eighteenth-early nineteenth

century to post-Civil War, probably twentieth century (Boisseau/Young and Sydnor farmsteads);

standing structures

dating from the late nineteenth century to present (houses east of Church Road and south of the forks).

These overlapping frameworks permit examination of different elements of the rural social and economic continuum

at Five Forks. The development of the plantation system and the impact of slavery on tobacco plantations of the inner

Coastal Plain may be addressed at the "Chimneys," Boisseau/Young, and Sydnor sites. Since the buildings at the "Chimneys"

site evidently burned in 1851, this locus may reflect the occupation of the Fraser and Smithey families from the late eighteenth

century into the mid-nineteenth century without subsequent post-Civil War occupation.

The Boisseau/Young and Sydnor farmsteads reflect a longer continuum, possibly from the colonial period into

the twentieth century. It may be possible to define different spatial distributions associated with the changing social relationships

prior to and following the Civil War. As is often the case on sites with occupational sequences that extend into the

twentieth century, however, evidence of the early phases of occupation may be damaged or eradicated and thus difficult to

recover. A focus upon post-Civil War agricultural and domestic activities may be gained by examining the yards associated

with the standing structures.

Various themes developed by the National Register for Historic Places are incorporated into specific contexts

by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (1991, 1993). The themes that are relevant to the Five Forks Unit are listed

with examples of known or probable archaeological remains indicative of each theme:

domestic: single dwelling, secondary structure or outbuilding, trash deposit, farmstead; prehistoric hunting/gathering

camp.

education: site of early nineteenth-century schoolhouse at forks.

funerary: graves, related

to both domestic and military occupations.

subsistence/agriculture: processing (tobacco barn), agricultural field,

animal facility (barns), agricultural outbuilding.

industry/processing/extraction: prehistoric lithic workshop?

ethnicity/immigration:

occupation of African-Americans as slaves and free farmers prior to Civil War and emancipated inhabitants following the Civil

War.

settlement patterns: distribution of prehistoric sites; spatial relationships of agricultural fields and

farm buildings both within a given plantation and between plantations.

military/defense: earthworks (primarily

Confederate) and spread of military artifacts from April 1, 1865, battle of Five Forks.

This final theme possesses particular interest for the National Park Service since it provided the rationale

for federal acquisition of the land. Those portions of the earthworks that do remain should be carefully maintained. As

mentioned previously, the distribution of Civil War artifacts within the Five Forks Unit has probably been heavily impacted

by decades of relic collecting prior to creation of the park. As this report has attempted to demonstrate, however, the battle

of Five Forks, although of national importance, represents simply one component in a sequence of cultural occupations with

historic and probably prehistoric dimensions.

| Battle of Five Forks Painting |

|

| Battle of Civil War Five Forks Battlefield Painting |

Sources: Department of Anthropology at the University of Maryland, © 2003-2005

University of Maryland; Civil War Trust (online at civilwar.org)

|