|

Battle of Franklin

Franklin Civil War History

Battle of Franklin

Other Names: Second Battle of Franklin, Battle of Franklin

Two

Location: Williamson County

Campaign: Franklin-Nashville Campaign (1864)

Date(s): November 30, 1864

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield [US]; Gen. John B. Hood [CS]

Forces Engaged: IV and XXIII Army Corps (Army of the Ohio and

Cumberland) [US]; Army of Tennessee [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 8,587 total (US 2,326; CS 6,261)

Result(s): Union victory

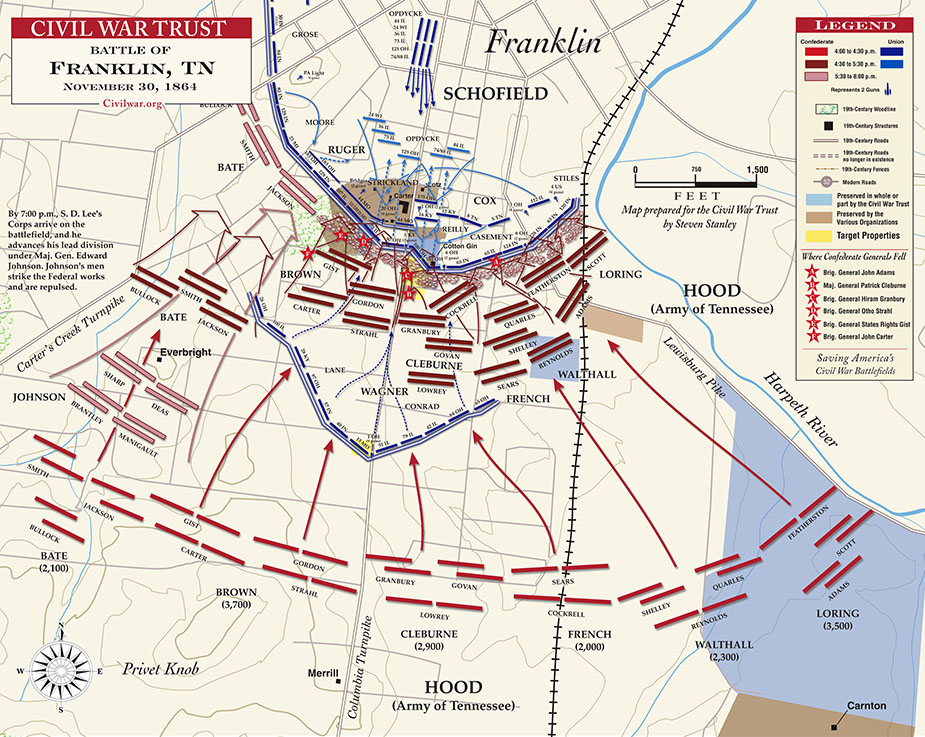

| Battle of Franklin Map |

|

| Battle of Franklin Battlefield Map |

Introduction: Having lost a good opportunity at Spring Hill to

hurt significantly the Union Army, Gen. John B. Hood marched in rapid pursuit of Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield’s retreating

Union army. Schofield’s advance reached the southern edge of Franklin about sunrise on November 30 and quickly

formed a defensive line in the works thrown up by the Yankees in the spring of 1863. Schofield wished to remain in Franklin

to repair the bridges and get his supply trains over them. Skirmishing at Thompson’s Station and elsewhere delayed Hood’s

march, but, around 4:00 pm, he marshaled a frontal attack against the Union perimeter. Two Federal brigades holding a forward

position gave way and retreated to the inner works, but their comrades ultimately held in a battle that caused frightening

casualties. When the battle ceased, after dark, six Confederate generals were dead or had mortal wounds. Despite this terrible

loss, Hood’s army, late, depleted and worn, crawled on toward Nashville.

Background: Following his defeat in the Atlanta Campaign, Hood had hoped to lure

Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman into battle by disrupting his railroad supply line from Chattanooga to Atlanta. After a brief

period in which he pursued Hood, Sherman decided instead to cut his main army off from these lines and "live off the land"

in his famed March to the Sea from Atlanta to Savannah. By doing so, he would avoid having to defend hundreds of miles of

supply lines against constant raids, through which he predicted he would lose "a thousand men monthly and gain no result"

against Hood's army.

Sherman's march left the aggressive General Hood unoccupied, and his Army of Tennessee could choose

several options in attacking Sherman or falling upon his rear lines. The task of defending Tennessee and the rearguard against

Hood fell to Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, commander of the Army of the Cumberland. The principal forces available in Middle

Tennessee were IV Corps of the Army of the Cumberland, commanded by Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley, and XXIII Corps of the Army

of the Ohio, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Schofield, with a total strength of about 30,000. Another 30,000 troops under Thomas's

command were in or moving toward Nashville.

Rather than trying to chase Sherman in Georgia, Hood decided that he would attempt a major offensive

northward, even though his invading force of 39,000 would be outnumbered by the 60,000 Union troops in Tennessee. He would

move north into Tennessee, defeat portions of Thomas's army in detail before they could concentrate, seize the important manufacturing

and supply center of Nashville, and continue north into Kentucky, possibly as far as the Ohio River. Hood even expected to

pick up 20,000 recruits from Tennessee and Kentucky in his path of victory and then join up with Robert E. Lee's army in Virginia,

a plan that defied reason. Hood spent the first three weeks of November quietly supplying the Army of Tennessee in northern

Alabama in preparation for his offensive.

| Battle of Franklin Map |

|

| First Battle of Franklin Map |

The Army of Tennessee marched north from Florence, Alabama, on November

21, and indeed managed to surprise the Union forces, the two halves of which were 75 miles apart at Pulaski, Tennessee, and

Nashville. With a series of fast marches that covered 70 miles in three days, Hood tried to maneuver between the two armies

to destroy each in detail. But Union General Schofield, commanding Stanley's IV Corps as well as his own XXIII Corps, reacted

correctly with a rapid retreat from Pulaski to Columbia, which held an important bridge over the Duck River on the turnpike

north. Despite suffering losses from Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest's cavalry along the way, the Federals were able to reach

Columbia and erect fortifications just hours before the Confederates arrived on November 24. From November 24 to 29, Schofield

managed to block Hood at this crossing, and the "Battle of Columbia" was a series of mostly bloodless skirmishes and artillery

bombardments while both sides re-gathered their armies.

On November 28, Thomas directed Schofield to begin preparations for a withdrawal

north to Franklin. He was incorrectly expecting that Maj. Gen. A. J. Smith's XVI Corps arrival from Missouri was imminent

and he wanted the combined force to defend against Hood on the line of the Harpeth River at Franklin instead of the Duck River

at Columbia. Meanwhile, early on the morning of November 29, Hood sent Cheatham's and Stewart's corps north on a flanking

march. They crossed the Duck River at Davis's Ford east of Columbia, while two divisions of Lee's corps and most of the army's

artillery remained on the southern bank to deceive Schofield into thinking a general assault was planned against Columbia.

Now that Hood had outflanked him by noon on November 29, Schofield's army

was in critical danger. His command was split at that time between his supply wagons and artillery and part of the IV Corps,

which he had sent to Spring Hill nearly ten miles north of Columbia, and the rest of the IV and XXIII Corps marching from

Columbia to join them. In the Battle of Spring Hill that afternoon and night, Hood had a golden opportunity to intercept and

destroy the Union troops and their supply wagons, as his forces had already reached the turnpike separating the Union forces

by nightfall. However, because of a series of command failures along with Hood's premature confidence that he had trapped

Schofield, the Confederates failed to stop or even inflict much damage to the Union forces during the night. Both the Union

infantry and supply train managed to pass Spring Hill unscathed by dawn on November 30, and soon occupied the town of Franklin

12 miles to the north. That morning, Hood was surprised and furious to discover Schofield's unexpected escape. After an angry

conference with his subordinate commanders in which he blamed everyone but himself for the mistakes, Hood ordered his army

to resume its pursuit north to Franklin.

| Franklin Civil War History |

|

| Battle of Franklin |

Battle: The Battle of Franklin was fought on November

30, 1864, at Franklin, Tennessee, as part of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign of the American Civil War. It was one of the

worst disasters of the war for the Confederate States Army. Confederate Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood's Army of Tennessee conducted

numerous frontal assaults against fortified positions occupied by the Union forces under Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield and was

unable to break through or to prevent Schofield from a planned, orderly withdrawal to Nashville.

The Confederate assault

with eighteen brigades of almost 20,000 men, sometimes called the "Pickett's Charge of the West", resulted in devastating

losses to the men and the leadership of the Army of Tennessee—fourteen Confederate generals (six killed or mortally

wounded, seven wounded, and one captured) and 55 regimental commanders were casualties. After its defeat against Maj. Gen.

George H. Thomas in the subsequent Battle of Nashville, the Army of Tennessee retreated with barely half the men with which

it had begun the short offensive, and was effectively destroyed as a fighting force for the remainder of the war.

The 1864 Battle of Franklin

was the second military action in the vicinity. The Battle of Franklin (1863), commonly referred to as First Franklin, was

a minor action associated with a reconnaissance in force by Confederate cavalry leader Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn on April 10.

Aftermath: Following the failure of the assault,

Hood decided to end offensive actions for the evening and began to plan for a resumed series of attacks in the morning. Schofield

ordered his infantry to cross the river, starting at 11 p.m., despite objections from Cox that withdrawal was no longer necessary

and that Hood was weakened and should be counter-attacked. Schofield had received orders from Thomas to evacuate earlier that

day—before Hood's attack began—and he was happy to take advantage of them despite the changed circumstances. Although

there was a period in which the Union army was vulnerable, outside its works and straddling the river, Hood did not attempt

to take advantage of it during the night. The Union army began entering the breastworks at Nashville at noon on December 1,

with Hood's damaged army in pursuit.

The devastated Confederate force

was left in control of Franklin, but its enemy had escaped again. Although he had briefly come close to breaking through in

the vicinity of the Columbia Turnpike, Hood was unable to destroy Schofield or prevent his withdrawal to link up with Thomas

in Nashville. And his unsuccessful result came with a frightful cost. The Confederates suffered 6,252 casualties, including

1,750 killed and 3,800 wounded. An estimated 2,000 others suffered less serious wounds and returned to duty before the Battle

of Nashville. But more importantly, the military leadership in the West was decimated, including the loss of perhaps the best

division commander of either side, Patrick Cleburne. Fourteen Confederate generals (six killed or mortally wounded, seven

wounded, and one captured) and 55 regimental commanders were casualties. The six generals killed or mortally wounded were

Cleburne, John C. Carter, John Adams, Hiram B. Granbury, States Rights Gist, and Otho F. Strahl. The wounded generals were

John C. Brown, Francis M. Cockrell, Zachariah C. Deas, Arthur M. Manigault, Thomas M. Scott, and Jacob H. Sharp. Brig. Gen.

George W. Gordon was captured.

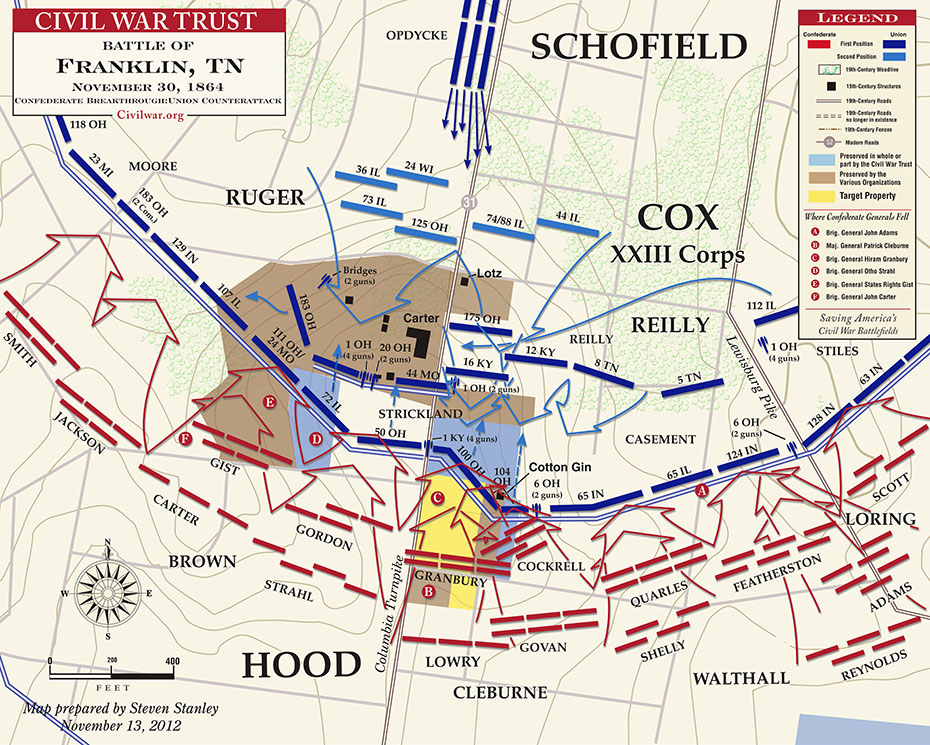

| Franklin Civil War Map |

|

| Battle of Franklin "Breakthrough" Map |

Union losses were reported as only 189 killed, 1,033 wounded, and 1,104

missing. It is possible that the number of casualties was under-reported by Schofield because of the confusion during his

army's hasty nighttime evacuation of Franklin. The Union wounded were left behind in Franklin. Many of the prisoners, including

all captured wounded and medical personnel, were recovered on December 18 when Union forces re-entered Franklin in pursuit

of Hood.

The

Army of Tennessee was all but destroyed at Franklin. Nevertheless, rather than retreat and risk the army dissolving through

desertions, Hood advanced his 26,500 man force against the Union army now combined under Thomas, firmly entrenched at Nashville.

Hood and his department commander Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard requested reinforcements, but none were available. Strongly outnumbered

and exposed to the elements, Hood was attacked by Thomas on December 15–16 at the Battle of Nashville, defeated decisively

and pursued aggressively, retreating to Mississippi with just under 20,000 men. The Army of Tennessee never fought again as

an effective force and Hood's career was ruined.

(Sources and related reading below.)

Sources: Civil War Trust

Maps (civilwar.org); National Park Service; Connelly, Thomas L. Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee 1862–1865. Baton

Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971. ISBN 0-8071-2738-8; Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History

of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5; Hood, John Bell. Advance and Retreat: Personal

Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-8032-7285-9;

Horn, Stanley F. The Army of Tennessee: A Military History. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1941. OCLC 2153322; Jacobson, Eric

A., and Richard A. Rupp. For Cause & for Country: A Study of the Affair at Spring Hill and the Battle of Franklin. Franklin,

TN: O'More Publishing, 2007. ISBN 0-9717444-4-0; Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6; Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Sherman's March: Atlanta

to the Sea. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1986. ISBN 0-8094-4812-2; Sword, Wiley. The Confederacy's Last Hurrah: Spring

Hill, Franklin, and Nashville. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993. ISBN 0-7006-0650-5; Welcher, Frank J. The Union

Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 2, The Western Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

ISBN 0-253-36454-X.

|