|

Battle of Washington

North Carolina Civil War History

Battle of Washington

Other Names: Siege of Washington

Location: Beaufort County

Campaign: Longstreet's Tidewater Operations (February-May 1863)

Date(s): March 30-April 20, 1863

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. John G. Foster [US]; Maj. Gen.

D. H. Hill [CS]

Forces Engaged: 6 regiments and artillery units [US]; Hill’s

Division [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 100 total

Result(s): Inconclusive (Confederates withdrew.)

Introduction: The Battle of Washington, aka Siege of Washington, took

place from March 30 to April 20, 1863, in Beaufort County, North Carolina, as part of Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's

Tidewater operations during the American Civil War (1861-1865). Although the Southerners would fail in its attempt to dislodge

the Federals in Washington during 1863, it would succeed in April of 1864, only to relinquish the city once more to the Federals

in November of that year. Washington would remain under Union occupation for the remainder of the war.

| Map of North Carolina Civil War Battlefields |

|

| Battle of Washington, Siege of Washington, and later known as the Burning of Washington |

| Siege of Washington |

|

| Battle of Washington |

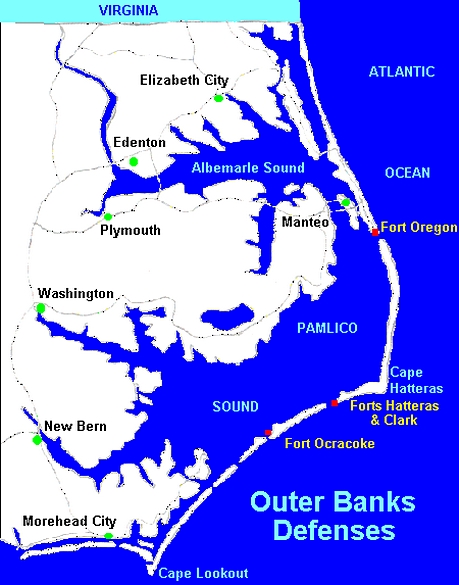

Background: After the culmination of Burnside's North

Carolina Expedition (February-June 1862) little attention had been given to North Carolina by the Confederate Army. Union

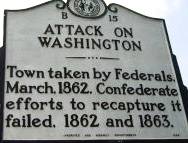

forces had captured Washington, North Carolina, on March 20, 1862, just days after it captured New Bern during the Burnside Expedition.

On September 6, 1862, a small expedition under the command of Confederate

Colonel S. D. Pool arranged for an attack on the Federal garrison at Washington, N.C., with the objective to retake the

town. This town was held by a force under Colonel Potter, of the First North Carolina Union Cavalry. Pool's force consisted of two companies from the Seventeenth North Carolina Regiment, two companies from

the Fifty-fifth North Carolina under Capt. P. M. Mull, 50 men under Captain MacRae from the Eighth North Carolina, and 70

men of the Tenth North Carolina Artillery acting as infantry and commanded by Captain Manney. This force dashed into Washington

in the early morning, surprising the garrison, and after a hot fight withdrew, taking several captured guns. The Union gunboat

Picket, stationed there, was blown up just as her men were called to quarters to fire on the Confederates, and nineteen of

her men were killed and wounded. The Confederates inflicted in this action a loss of 44, and suffered a loss of 13 killed

and 57 wounded. This as truly a North Carolina fight, the Brothers War, as all the participants were from this State.

In December 1862 a Union expedition from New Bern destroyed the railroad

bridge at Goldsboro, N.C. along the vital Wilmington and Weldon Railroad. This expedition caused only temporary damage to

the railroad, but did prompt Confederate authorities to devote more attention to the situation along the coast of Virginia

and North Carolina.

Following the Confederate victory at Fredericksburg, December 1862, General

Robert E. Lee felt confident enough to dispatch a large portion of his army to deal with Union occupation forces along the

coast. The whole force was put under the command of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. While Longstreet personally operated against

Suffolk, Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill, March 1863, led a column which moved against Federal garrisons at New Bern and Washington,

North Carolina. Maj. Gen. John G. Foster, commanding the Department of North Carolina, was responsible for the overall defense

of the Union garrisons along the North Carolina coast. After Hill's attack against New Bern failed in April 1863, Foster arrived

in Washington to take personal command of the garrison.

| Battle of Washington & Oakdale Cemetery |

|

| Battle of Washington & Oakdale Cemetery |

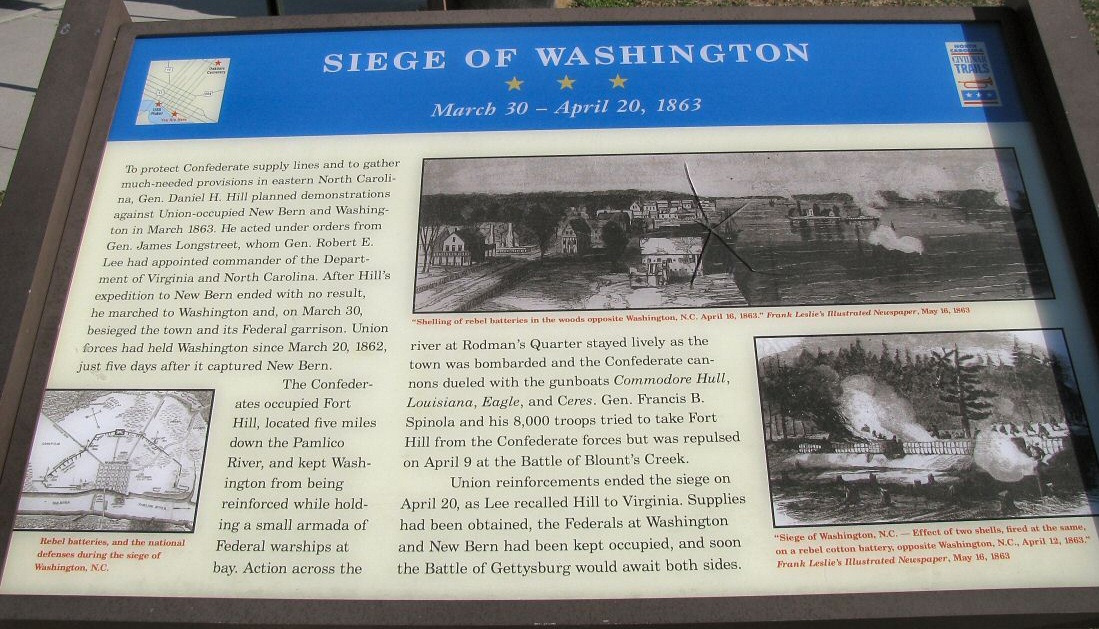

Siege: Foster,

a West Point trained Army engineer, put his skills to good use improving the town's defenses as well as employing the use

of three gunboats in the defense. By March 30, the town was ringed with fortifications, and Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett's

brigade began the investment of Washington. Meanwhile, Hill established batteries as well as river obstructions along the

Tar River to impede reinforcements. He also posted two brigades south of Washington to guard for any relief efforts coming

overland from New Bern. The Confederates sent a reply to Foster demanding surrender. Foster replied saying "If the Confederates

want Washington, come and get it." Despite this defiance, Foster lacked the strength to dislodge the besiegers, and Hill was

under orders to avoid an assault at the risk of sustaining heavy casualties. Thus, the engagement devolved into one of artillery,

and even so the Confederates limited their bombings to conserve their ammunition. In time both sides were running low on supplies,

and conditions grew miserable in the rain and mud. Despite the lack of progress against Washington, Hill was accomplishing

a vital objective in the form of foraging parties so long as the Federals were pinned down.

A Federal relief column under Brig. Gen. Henry Prince sailed up the Tar

River. Once Prince saw the Rebel batteries, he simply turned the transports around. A second effort under Brig. Gen. Francis

Barretto Spinola moved overland from New Bern. Spinola was defeated along Blount's Creek and returned to New Bern. Foster

decided that he would escape Washington and personally lead the relief effort leaving his chief-of-staff, Brig. Gen. Edward

E. Potter in command at Washington. On April 13, the USS Escort braved the Confederate batteries and made its way into Washington.

The Escort delivered supplies and reinforcements in the form of a Rhode Island regiment. It was aboard this ship on April

15 that Foster made his escape. The ship was badly damaged and the pilot mortally wounded, but Foster made it out.

| Battle and Siege of Washington |

|

| Battle and Siege of Washington |

About the same time Foster made an escape, Hill was faced with numerous

reasons that ultimately led to his withdrawal: the completion of his foraging efforts, Union supplies reaching the Federal

garrison, and finally a message arrived from Longstreet requesting reinforcements for an assault on Suffolk. Hill broke off

the siege on April 15 and began to withdraw Garnett's brigade fronting Washington's defenses.

Meanwhile, Foster had made it back to New Bern and immediately began organizing

a relief effort. He ordered General Prince to march along the railroad towards Kinston to hold off Confederates in the vicinity

of Goldsboro, while Foster personally led a second column north from New Bern towards Blount's Creek where General Spinola

had earlier been turned back. On April 18, Foster ordered Spinola to drive the Confederates from their road block at Swift

Creek guarding the direct road from Washington to New Bern. At the same time, General Henry M. Naglee attacked the Confederate

rear guard near Washington capturing several prisoners and a regimental battle flag. On April 19th Foster returned to the

Washington defenses and by April 20 the Confederates had completely withdrawn from the area.

Aftermath: Apart from raids conducted by Foster and Potter,

North Carolina remained relatively quiet until 1864 when Robert E. Lee was able to spare troops for another operation against

Union enclaves along the coast.

When the Confederates later moved on and captured

Plymouth, North Carolina, mid-April 1864, it would lead to the complete Federal withdrawal from nearby Washington on April

28, 1864. During the evacuation, the town was intentionally burned by Federal troops. Union Gen. Palmer, in an order condemning

the atrocities by his troops, used these words: "It is well known that the army vandals did not even respect the charitable

institutions, but bursting open doors of the Masonic and Odd Fellows' lodge, pillaged them both and hawked about the streets

the regalia and jewels. And this, too, by United States troops! It is well known that both public and private stores were

entered and plundered, and that devastation and destruction ruled the hour." Official Records, XXXIII, p. 310.

| Civil War on the North Carolina Coast |

|

| Battle of Washington |

Analysis: While Gen. Longstreet operated against Suffolk, Gen.

D. H. Hill’s column moved against the Federal garrison of Washington, North Carolina. By March 30, 1863, the town was

ringed with fortifications, but the Confederates were unable to shut off supplies and reinforcements arriving by ship. After

a week of confusion and mismanagement, D. H. Hill, during the Siege of Washington, was maneuvered out of his siege works and withdrew on April 15, 1863.

Washington remained under Federal control until

April 26, 1864, when, as a result of the Confederate victory at nearby Plymouth, during Operations against Plymouth, Union Brig. Gen. Edward Harland was ordered to withdraw from the town. For four days

the evacuating troops pillaged Washington, destroying what they could not carry. As the final detachments were preparing to

leave Washington on April 30, a fire started in the riverfront warehouse district, spreading quickly, until about one half

of the city was in ashes. General Robert F.

Hoke entered Washington finding “a ruined city…a sad scene—mostly…chimneys and Heaps of ashes to mark

the place where Fine Houses once stood, and the Beautiful trees, which shaded the side walks, burnt, some all most to a coal.”

Hoke left the 6th North Carolina to defend Washington and to assist its citizens. A reversal of fortune would come in about

six months during November 1864. Following the Union’s recapture of Plymouth, Washington and the whole sound region,

again fell under Federal control.

The cities and ports along the North Carolina coast would henceforth receive little

if any Confederate military intervention, because Gen. Robert E. Lee requested the majority of North Carolina's units moved

into Virginia in an attempt to dislodge the Union elephant there.

| Union Capture Washington |

|

| Battle of Washington |

| Burning of Washington |

|

| Battle of Washington |

| Confederate Monument at Washington, N.C. |

|

| Battle of Washington Memorial |

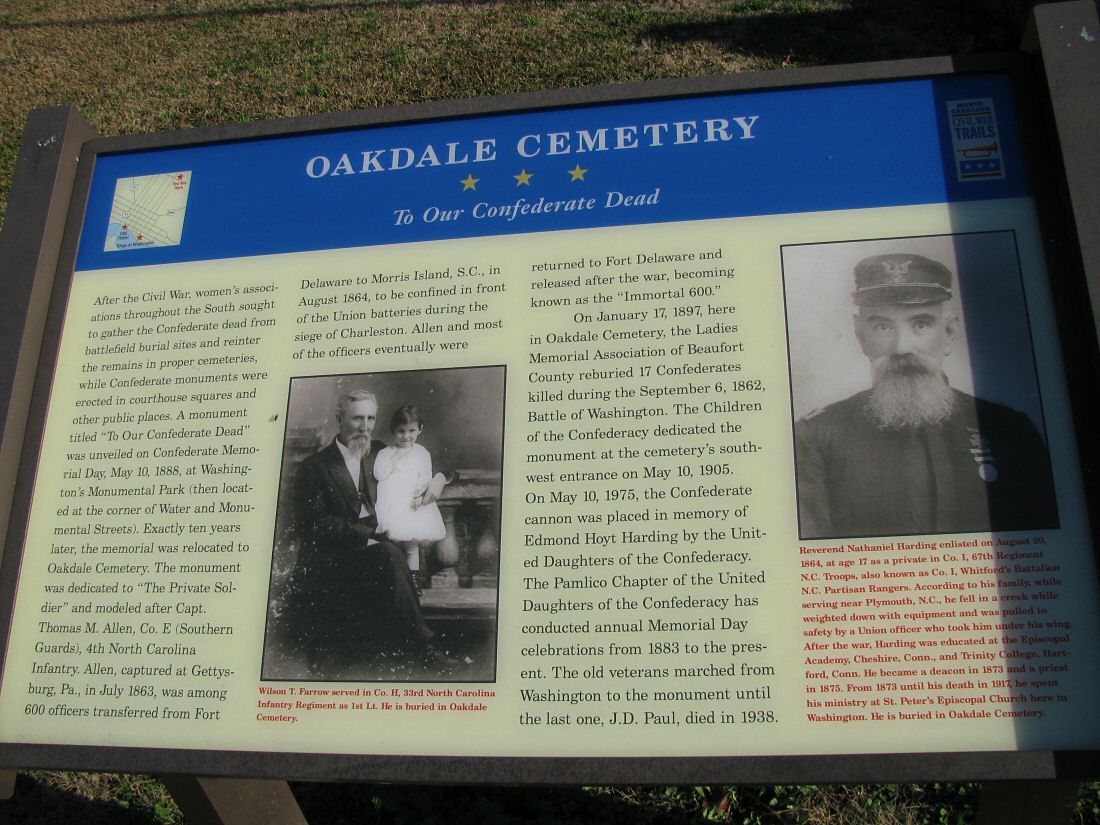

(About) Confederate Soldiers Monument. To the

memory of soldiers killed in the defense of Washington on September 6, 1862. Located at Oakdale Cemetery, N. Market St, Washington,

N.C.

| Battle of Washington Monument |

|

| Battle of Washington Memorial |

Washington: In

its infancy, Washington was a regional shipping center because of its strategic location at the junction of inland and

coastal rivers. The shipping heritage is evident in some waterfront commercial buildings from that era. The architecture in

the large residential and commercial Historic District captures later phases of Washington's history and development. Main

Street in Washington's Historic Downtown is flanked by 19th & early 20th century commercial buildings punctuated with

ornate brickwork.

In 1776, Washington, North Carolina, became the first town in the United States named in honor of George Washington. It was

outlined in 1771, and was originally called Forks of the Tar River. It was incorporated

in 1782. Washington is also the perfect starting

point for the Historic Albemarle Tour - an expedition of sites throughout the Inner Banks such as the historic village of

Bath, once home to the ruthless pirate, Blackbeard. Bath is also North Carolina's oldest town with a number of historical

landmarks, including the state's oldest church. Closer to home, Washington's entire waterfront district is listed on the National

Register of Historic Places. It features nearly 30 unique structures dating from 1780. So spend a weekend revisiting the past

from the heart (and soul) of the Inner Banks - historic Washington.

(Sources listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended Reading: The

Civil War in Coastal North Carolina (175 pages) (North Carolina Division of Archives and History). Description: From the drama of blockade-running to graphic descriptions of battles

on the state's islands and sounds, this book portrays the explosive events that took place in North Carolina's

coastal region during the Civil War. Topics discussed include the strategic importance of coastal North Carolina, Federal occupation of coastal areas, blockade-running, and the impact of

war on civilians along the Tar Heel coast.

Advance to:

Recommended Reading: Storm

over Carolina: The Confederate Navy's Struggle for Eastern North Carolina. Description: The struggle for control of the eastern

waters of North Carolina during the War Between the States

was a bitter, painful, and sometimes humiliating one for the Confederate navy. No better example exists of the classic adage,

"Too little, too late." Burdened by the lack of adequate warships, construction facilities, and even ammunition, the

South's naval arm fought bravely and even recklessly to stem the tide of the Federal invasion of North

Carolina from the raging Atlantic. Storm

Over Carolina is the account of the Southern navy's struggle in North

Carolina waters and it is a saga of crushing defeats interspersed with moments of brilliant and even

spectacular victories. It is also the story of dogged Southern determination and incredible perseverance in the face

of overwhelming odds. Continued below...

For most of

the Civil War, the navigable portions of the Roanoke, Tar, Neuse, Chowan, and Pasquotank rivers were

occupied by Federal forces. The Albemarle and Pamlico sounds, as well as most of the coastal towns and counties, were also

under Union control. With the building of the river ironclads, the Confederate navy at last could strike a telling blow against

the invaders, but they were slowly overtaken by events elsewhere. With the war grinding to a close, the last Confederate vessel

in North Carolina waters was destroyed. William T. Sherman

was approaching from the south, Wilmington was lost, and the

Confederacy reeled as if from a mortal blow. For the Confederate navy, and even more so for the besieged citizens of eastern

North Carolina, these were stormy days indeed. Storm Over Carolina describes their story, their struggle, their history.

Recommended

Reading: American Civil

War Fortifications (1): Coastal brick and stone forts (Fortress). Description: The 50 years before the American Civil War saw a boom in the construction of coastal forts

in the United States of America. These

stone and brick forts stretched from New England to the Florida Keys, and as far as the Mississippi River.

At the start of the war some were located in the secessionist states, and many fell into Confederate hands. Although a handful

of key sites remained in Union hands throughout the war, the remainder had to be won back through bombardment or assault.

This book examines the design, construction and operational history of those fortifications, such as Fort

Sumter, Fort Morgan

and Fort Pulaski,

which played a crucial part in the course of the Civil War.

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in North Carolina. Description: Numerous

battles and skirmishes were fought in North Carolina during

the Civil War, and the campaigns and battles themselves were crucial in the grand strategy of the conflict and involved some

of the most famous generals of the war. John Barrett presents the complete story of military engagements across the state,

including the classical pitched battle of Bentonville--involving Generals Joe Johnston and William Sherman--the siege of Fort Fisher, the amphibious

campaigns on the coast, and cavalry sweeps such as General George Stoneman's Raid.

Recommended Reading: Confederate Military History Of North Carolina: North Carolina In

The Civil War, 1861-1865. Description:

The author, Prof. D. H. Hill, Jr., was the son of Lieutenant General Daniel Harvey Hill (North

Carolina produced only two lieutenant generals and it was the second highest rank in the army) and

his mother was the sister to General “Stonewall” Jackson’s wife. In Confederate

Military History Of North Carolina, Hill discusses North Carolina’s massive task of preparing and mobilizing

for the conflict; the many regiments and battalions recruited from the Old North State; as well as the state's numerous

contributions during the war. Continued below...

During Hill's

Tar

Heel State study, the reader begins with

interesting and thought-provoking statistical data regarding the 125,000 "Old

North State" soldiers that fought

during the course of the war and the 40,000 that perished. Hill advances with the Tar Heels to the first battle at Bethel, through numerous bloody campaigns and battles--including North Carolina’s

contributions at the "High Watermark" at Gettysburg--and concludes with Lee's surrender at

Appomattox.

Sources: National Park Service; Confederate Military History Of North Carolina,

by D. H. Hill, Jr.; North Carolina Museum of History; North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources; Official Records

of the Union and Confederate Armies; National Archives; John G. Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina (1963); William R.

Trotter, Ironclads and Columbiads, The Civil War in North Carolina: The Coast (1989); Richard A. Sauers, The Burnside Expedition

in North Carolina (1996); visitwashingtonnc.com/history; North Carolina Office of Archives and History; ci.washington.nc.us

|