|

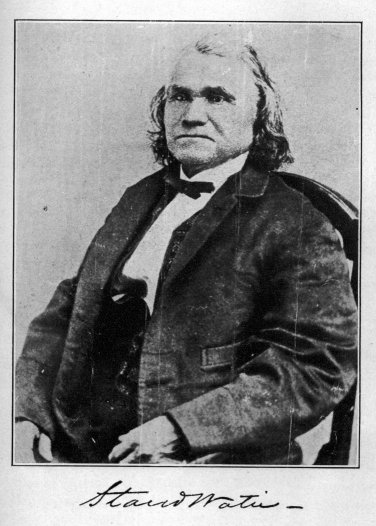

Cherokee Chief Stand Watie

?

Cherokee Chief Stand Watie exhibited

bravery and leadership while fighting for two lost causes. So who was Chief Watie? Was he infamous or famous? We will explore

the history of legendary Stand Watie and then you decide.

| Cherokee Chief Stand Watie |

|

| (December 12, 1806 - September 9, 1871) |

By Jim Stebinger

Always a clear-thinking man, even on a day when kinsmen were murdered and

vengeful fellow Cherokees dogged his heels, Stand Watie knew that he had to maintain a straight

face and stay calm if he wanted to remain alive.

The son of an old friend had ridden from one of three murder scenes and brought

him a warning. The youth remained collected and spoke calmly with Watie, who was inside a small store he kept in northeastern

Indian Territory.

Knowing that enemies could be listening, the young man bargained loudly for sugar and softly told Watie what had happened

and where to find the horse called Comet standing bridled and ready. Deliberately, Watie left the store and rode off safely.

He would remain in jeopardy for almost six years.

The murders, which took place on the

morning of June 22, 1839, pushed Watie into the leadership of a small and unpopular Cherokee faction for the rest of his life.

The tribal majority blamed Watie and his faction for the removal of the Cherokees along what became known as the Trail of Tears. Watie's uncle, the prominent chief Major Ridge, Watie's cousin John Ridge and Watie's brother Elias Boudinot

(also known as Buck Watie) all died that day in the new Cherokee Nation in the West. Stand Watie faced few worse days in his

adventurous and violent life that saw him become a Confederate brigadier general. On the losing side twice in his life, he

had intimate familiarity with dashed hopes and lost causes.

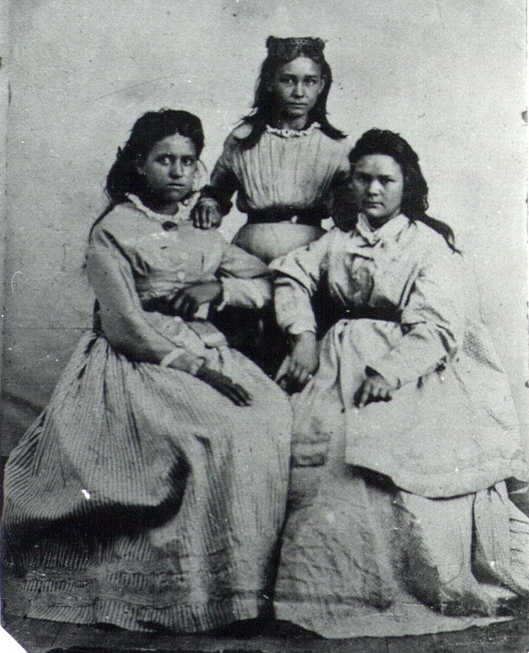

| Daughters of Chief Stand Watie |

|

| Daughters of Stand Watie, ca. 1870 |

The Cherokees, linguistic kinsmen of the Iroquois, numbered about 30,000 in 1605

and lived in what is now Georgia, Tennessee and western North Carolina. Smallpox and other diseases struck often in the 1700s. By 1800, the Cherokee

population was probably about 16,000. In the Georgia Compact of 1802, Georgia

gave up the land that became Alabama and Mississippi

with the understanding that the federal government would force the Cherokees west. The Cherokees refused, and Washington stalled. Most of the tribe decided that assimilation gave them the best hope

to stay in their homeland. Cherokees began to take on white ways, seeking education, material profit and cultural interchange.

Assimilation, though, didn't work as planned. Growing economic power on the part of the Cherokees enraged white Georgians,

who redoubled expulsion efforts.

To some natives the solution was obvious, and one-third of the tribe had moved west

of the Mississippi River by 1820. They were eventually pushed all the way to what would become

Oklahoma. The bulk of the tribe went to court, and the debate

over relocation simmered. Meanwhile, the tribe (which numbered about 14,000 in the Southeast in the mid-1820s) began to suffer

a debilitating internal split. Perhaps 20 percent of the Cherokee people successfully adapted to white lifestyles, some becoming

affluent Southern slave-owning planters.

Among the most prominent slave-owning Cherokee aristocrats were the Watie and Ridge

families. The faction of the tribe headed by the Ridges and Waties owned most of the estimated 1,600 slaves held by tribesmen.

Cherokee slave owners tended to work side by side with their chattels, children were born free, and intermarriage was not

forbidden. Only about 8 percent of tribal members (1 percent of full-blooded families) actually owned slaves. Because of the

influence of mission schools, many Cherokees were intensely anti-slavery. Poorer than the Ridge-Watie faction, the traditionalists

had neither the money nor the inclination to move West.

In 1827, the Cherokees created their first central government to better deal with

the white world. At a convention the next year, John Ross was elected principal chief--a post he held until his death in 1866. Ross, born in 1796 in Tennessee, was mostly Scottish, having only one-eighth Cherokee blood. But he was Cherokee

to the core and enormously popular.

His rivals turned out to be the sons of old-time full bloods. Major Ridge and his

brother, David Watie (or Oowatie), were descended from warrior chiefs. Both men married genteel white women and rose in society,

dressing and acting like planters. The family was close, and family members wrote more often and better than most whites of

the time. Some 2,000 family letters were found in 1919. Following Sequoyah's development of a syllabary in 1821, Cherokees took enthusiastically to reading and writing. When Stand Watie began writing

is not certain, but his only surviving letters date to the Civil War.

Stand Watie was born in Georgia,

probably in 1806; his early life is obscure. He was educated at a mission school, but less thoroughly than his brother Elias

Boudinot, who was born Buck Watie but took the name of a white benefactor. Elias became a newspaper editor, and Stand held

the job briefly during his brother's absence. Stand Watie married several times, losing a number of wives and children to

disease. The family did not record dates and details.

Watie's rivalry with John Ross, whose bywords were unity and opposition

to removal, slowly began to grow after 1832. Most of the Cherokees who had not moved West in the removal treaties of 1817

and 1819 continued to be against relocation, and Ross was their spokesman. The Ridge faction thought relocation to be in the

best interests of the people. Major Ridge, a full-blooded Cherokee, and his son John

Ridge felt that the educated and wealthy Cherokees could probably survive in Georgia but that the others would be led into drunkenness

and then cheated and oppressed. War would be the inevitable result. Each faction thought the other was corrupt. The Ridge-Watie

party allied itself with U.S. President Andrew Jackson and his supporters, and connived behind the backs of the Cherokee councilmen,

who usually opposed them.

The atmosphere became poisonous as rival Cherokee delegations went to

Washington, D.C., with different

plans, and President Jackson played both sides against each other--fostering allegations of bribe-taking. In 1835 the issue

came to a head. Ridge's faction helped draft a treaty that would require Cherokee removal west of the Mississippi in return for about $5 million. Ross and the council rejected the treaty, holding

out for $20 million and other terms; they would not move on Ridge-Watie terms. By October it was clear that most Cherokees

sided with Ross. It was also clear that the government would not pay $20 million.

Then, in December 1835, the Ridge-Watie party committed what amounted to suicide.

Major Ridge, John Ridge and the Watie brothers

were the only prominent Cherokees to sign the Treaty of New Echota, in Georgia,

on December 29. A free-blanket offer attracted some 300 to 500 people--probably 3 percent of the tribe--to the signing place.

Only about 80 to 100 people eligible to vote were present. Ross and the legitimate council were nowhere near. The treaty was

roundly denounced--even by such unlikely allies as Davy Crockett and Daniel Webster. Cherokees in the East had to leave the Southeast in return

for a payment of $15 million and 800,000 acres in Indian Territory (in what would become northeastern Oklahoma

and part of Kansas). The Cherokees were to be removed within

two years. The Ridge-Watie faction ("treaty party") thought the terms generous--that they had gotten a good price.

Whether or not the terms were generous, the treaty was a disgrace, as

it was opposed by some 90 percent of the tribe. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled the treaty invalid, but President Jackson refused

to void it. The Martin van Buren administration did likewise. Ross and his "anti-treaty party" fought a losing court battle,

and they were not well-prepared for removal when it began. In 1837, only about 2,000 Cherokees went West; most of the others

held out, perhaps not believing they would be forced to leave their homeland.

The so-called Trail of Tears (the Cherokees called it Nunna daul Tsuny,

"Trail Where We Cried") came in 1838, when Federal troops and Georgia militia removed the holdout tribe members to Indian

Territory (about 1,000 avoided capture by hiding in the mountains). As many as 4,000 Cherokees may have died from

disease, hunger, cold and deliberate brutality by volunteer Georgia troops and regulars led by a reluctant General Winfield

Scott. The Ridge-Watie parties had been among the first to depart to the new country, arriving in 1837. They had gone in comfort

and had located themselves on choice Indian Territory land. Because most of the Cherokees

who followed suffered during the migration and after their arrival in the West, resentment against the Ridges and Waties grew.

Historians disagree about the level of brutality on the Trail of Tears,

but most historians agree the suffering and death continued in the West, mainly because of epidemic diseases. And historians

also agree that the treaty was invalid, the military high-handed, the preparations and logistics inefficient, and the intent

rapacious. The Cherokees certainly thought so, and feelings against the treaty party ran higher and higher. Ironically, Major

Ridge himself had helped write the death penalty into the Cherokee Constitution for those selling tribal land without authorization.

Many years earlier, he had killed a fellow chief named Doublehead who was convicted by the tribal council of such a land deal.

Clearly, Ridge knew the penalty.

More than 100 members of the anti-treaty party met at Double Springs

on June 21 and pronounced death sentences in secret--outside the council and without vested authority--purportedly to keep

John Ross from finding out about their plans. Either Ross had reached the end of his patience with his enemies--or he simply

could do nothing to stop the killings.

Death came early and with ritual touches for John Ridge at his Indian Territory home on Honey Creek,

near the northwest corner of Arkansas. About 30 killers

dragged him from his bed and into his front yard around dawn on June 22. They knifed him repeatedly before his distraught

family. Old Major Ridge, John's father, was ambushed a few hours later while riding past a small bluff on the road to Washington County, Ark. Rifle-toting

bushwhackers opened fire, hitting him five times. Boudinot, at about the same time, was going about his daily work, helping

a friend build a house near Park Hill, some miles from John Ridge's house. Three Cherokees approached him and told him they

needed to get medicine. Because Boudinot's tribal responsibilities included providing medicine, he followed, unsuspecting.

One of the men quickly dropped behind him and stabbed him in the back. Another axed him in the head.

Boudinot's brother, Stand Watie, was also apparently marked for death

that day. But Boudinot's cries on being stabbed were heard by friends. The youth who delivered the warning to Watie was probably

the son of the Reverend S.A. Worcester, a family friend. Watie's store was close to John

Ridge's home.

Because John Ross was proud of his ties to the average Cherokee and

was very popular among them, he was in a difficult position. He repudiated the murders, but he did not turn the killers in

and may actually have hidden some of them. He denied complicity and does not appear to have been directly involved. Former

President Jackson wrote to Watie and condemned "the outrageous and tyrannical conduct of John Ross and his self-created council....I

trust the President will not hesitate to employ all his rightfull [sic] power to protect you and your party from the tyranny

and murderous schemes of John Ross."

Jackson

didn't curb his habit of speaking from both sides of his mouth. He urged Watie to make peace but endorsed seeking vengeance

if Watie didn't get what he wanted. Watie formed a band of warriors, and Ross complained to Washington that he had to go armed among friends. The government ordered Watie to disband

his followers, to little avail.

Until 1846 the Cherokees were involved in a murderous internal feud.

As chief of his segment of the tribe, Watie authorized retaliation, and vengeance murders were common. Legend has encrusted

Watie's activities, giving him heroic courage and coolness and deadly fighting skills. His most documented exploit occurred

in an Arkansas grocery where he confronted James Foreman,

an alleged killer of Major Ridge. The two men had threatened each other frequently, but this day they bought each other a

drink. A challenge was quickly issued, and the drinks were hurled aside. Foreman had a big whip, which he used against Watie.

Watie stabbed Foreman when Foreman tried to hit him with a board. He then shot and killed the escaping Foreman. Watie successfully

argued self-defense at his trial.

The tribal situation was brutal. In one letter to Watie, a relative

recounted family news that included four treaty-related killings (and two scalpings), three hangings for previous killings

and two kidnappings. The letter said that intertribal murders were so common "the people care as little about hearing these

things as they would hear of the death of a common dog."

The Cherokees made internal peace in 1846--Watie and Ross reputedly

shaking hands--and sought to rebuild tribal prosperity in the West. Times were improving until the Civil War. Stand Watie

was a member of the Cherokee Tribal Council from 1845 to 1861. He declared his support for the Confederacy early on, but Ross

resisted at first. The Confederacy was successful in seeking alliances with Comanches, Seminoles, Osages, Chickasaws, Choctaws

and Creeks. Ross was finally forced into the Confederate alliance.

Watie raised a cavalry regiment and served the South with distinction and

enthusiasm. Another Cherokee regiment served under John Drew. In all, about 3,000 Cherokee men served the Confederacy during

the war. Watie was beloved by die-hard Confederates. Judge James M. Keyes of Pryor,

Okla., said: "I regard General Stand Watie as one of the bravest and most capable

men, and the foremost soldier ever produced by the North American Indians. He was wise in council and courageous in action."

Watie fought most of the war at the head of a band of very irregular

cavalry. He led with dash and imagination as they ambushed trains, steamships and Union cavalry. He also fought in one major

battle.

On March 7-8, 1862, Watie was part of Confederate Maj. Gen. Earl Van

Dorn's army of 16,000 men. They were in the region of Fayatteville, Ark., trying to encircle the right flank of Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis' 12,000-man army.

Curtis, who was on the defensive about 30 miles northeast of Fayatteville at Pea Ridge, discovered the plan and spoiled the

offensive. Van Dorn withdrew after two days of stubborn fighting, but Pea Ridge cemented Watie's reputation. He captured a

Union battery after a dramatic charge, and also proved skillful in withdrawal, helping to prevent a disaster. One of his soldiers

said: "I don't know how we did it but Watie gave the order, which he always led, and his men could follow him into the very

jaws of death. The Indian Rebel Yell was given and we fought like tigers three to one. It must have been that mysterious power

of Stand Watie that led us on to make the capture against such odds."

After the Battle of Pea Ridge, Drew's regiment deserted the Confederacy. Watie,

though, stuck to the Southern cause. Untrained as a soldier, he had good sense and cunning and was an effective guerrilla. "Stand Watie and his men, with the Confederate Creeks and others, scoured

the country at will, destroying or carrying off everything belonging to the loyal Cherokee," wrote 19th-century anthropologist

James Mooney. Watie was promoted to brigadier general on May 10, 1864, and on June 23, 1865, was the last Southern general

to capitulate. Watie returned to absolute devastation. (According to Mooney, the Cherokee population during the war was reduced

from 21,000 to 14,000.) Watie then fought some losing postwar battles. He was rebuffed in his bid for federal recognition

as Cherokee chief and was also rebuffed in efforts to rebuild his fortunes.

Watie's last years were careworn as his family dropped around him. All

his sons died before he died on September 9, 1871, and his two young daughters followed in 1873. But Confederate veterans

and sympathetic writers kept Watie's legend alive. He became the example of devotion to "the Cause." Even enemy Cherokees

came to respect his devotion to his beliefs, and "Stand" and "Watie" became common Cherokee first names.

Watie had displayed unfailing courage,

devotion, constant optimism and good humor--at least according to his friends. He never, they say, had a harsh word for his

family and never gave way to despair or dejection. In reality he was not a shining cavalier--his Indian troops sometimes reverted

to scalping and torture. He clearly was involved in shameful political skullduggery. But he was a man who fought hard for

his beliefs and stuck to his guns even when the odds were against him. He had supported two lost causes--the Ridges and then

the Confederacy--but he had never given up.

This article was written by Jim Stebinger and originally appeared in the October 1997 issue of Wild

West; Stand Watie photo National Archives; photo of Daughters is Image #16978 in the Stand Watie Collection.

Recommended

Reading: Rifles for Watie.

Description: This is a rich and sweeping novel-rich in its panorama

of history; in its details so clear that the reader never doubts for a moment that he is there; in its dozens of different

people, each one fully realized and wholly recognizable. It is a story of a lesser -- known part of the Civil War, the Western

campaign, a part different in its issues and its problems, and fought with a different savagery. Inexorably it moves to a

dramatic climax, evoking a brilliant picture of a war and the men of both sides who fought in it.

Recommended Reading: General

Stand Watie's Confederate Indians (University of Oklahoma Press). Description: American Indians were

courted by both the North and the South prior to that great and horrific conflict known as the American Civil War. This is

the story of the highest ranking Native American--Cherokee chief and Confederate general--Stand Watie, his Cherokee

Fighting Unit, the Cherokee, and the conflict in the West...

Recommended

Reading: Civil War in the Indian Territory,

by Steve Cottrell (Author), Andy Thomas (Illustrator). Review: From its beginning with the

bloody Battle of Wilson's Creek on August 10, 1861, to its end in surrender on June 23, 1865, the Civil War in the Indian Territory proved to be a test of valor and endurance for both

sides. Author Steve Cottrell outlines the events that led up to the involvement of the Indian

Territory in the war, the role of the Native Americans who took part in the war, and the effect this

participation had on the war and this region in particular. As in the rest of the country, neighbor was pitted against neighbor,

with members of the same tribes often fighting against each other. Cottrell describes in detail the guerrilla warfare, the

surprise attacks, the all-out battles that spilled blood on the now peaceful state of Oklahoma. Continued below...

In addition, he introduces

the reader to the interesting and often colorful leaders of the military North and South, including the only American Indian

to attain a general's rank in the war, Gen. Stand Watie (member of the Cherokee Nation). With outstanding illustrations by

Andy Thomas, this story is a tribute to those who fought and a revealing portrait of the important role they played in this

era of our country's history. Meet The Author: A resident of Carthage, Missouri, Steve Cottrell is a descendant of a Sixth Kansas Cavalry member who served

in the Indian Territory

during the Civil War. A graduate of Missouri Southern State College in Joplin,

Cottrell has participated in several battle reenactments including the Academy Award winning motion picture, "Glory". Active

in Civil War battlefield preservation and historical monument projects and contributor of a number of Civil War relics to

regional museums, Cottrell recently co-authored Civil War in the Ozarks, also by Pelican. It is now in its second printing.

Recommended Reading: The Blue, the Gray, and the Red: Indian Campaigns of the Civil War

(Hardcover: 288 pages). Description: Inexperienced Union and Confederate

soldiers in the West waged numerous bloody campaigns against the Indians during the Civil War. Fighting with a distinct geographical

advantage, many tribes terrorized the territory from the Plains to the Pacific, as American pioneers moved west in greater

numbers. These noteworthy--and notorious--Indian campaigns featured a fascinating cast of colorful characters, and were set

against the wild, desolate, and untamed territories of the western United

States. This is the first book to explore Indian conflicts that took place during the Civil

War and documents both Union and Confederate encounters with hostile Indians blocking western

expansion. Continued below...

From

Publishers Weekly: Beginning with the flight

of the Creeks into Union territory pursued by Confederate forces (including many of Stand Watie's Cherokees), this popular

history recounts grim, bloody, lesser-known events of the Civil War. Hatch (Clashes

of the Cavalry) also describes the most incredible incidents.... Kit Carson, who fought Apaches and

Navajos under the iron-fisted Colonel Carleton, arranged the Long Walk of the Navajos that made him infamous in Navajo history

to this day. The North's "Captain" Woolsey, a volunteer soldier, became a brutal raider of the Apaches. General Sibley, a

northerner and first Governor of Minnesota, oversaw the response to the Sioux Uprising of 1862 that

left several hundred dead. The slaughter of Black Kettle's Cheyennes at Sand Creek in

1864 by Colorado volunteers under Colonel Chivington,

a militant abolitionist whose views on Indians were a great deal less charitable, “forms a devastating chapter.”

Hatch, a veteran of several books on the Indian Wars that focus on George Armstrong Custer, has added to this clear and even-handed

account a scholarly apparatus that adds considerably to its value.

Recommended

Reading: The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War

(Hardcover). Description: This book offers a broad overview of the war as it affected the Cherokees--a social history of a

people plunged into crisis. The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War shows how the Cherokee people, who had only just begun to

recover from the ordeal of removal, faced an equally devastating upheaval in the Civil War. Clarissa W. Confer illustrates

how the Cherokee Nation, with its sovereign status and distinct culture, had a wartime experience unlike that of any other

group of people--and suffered perhaps the greatest losses of land, population, and sovereignty. Continued below…

No one questions

the horrific impact of the Civil War on America,

but few realize its effect on American Indians. Residents of Indian Territory

found the war especially devastating. Their homeland was beset not only by regular army operations but also by guerrillas

and bushwhackers. Complicating the situation even further, Cherokee men fought for the Union

as well as the Confederacy and created their own "brothers' war." About the Author: Clarissa W. Confer is Assistant Professor

of History at California University of Pennsylvania.

Cherokee Chief Stand Watie History, Cherokee Nation Oklahoma Indian Territory, Major Ridge, Trail

of Tears Details and Facts, Indian Removal, Confederate Battle of Pea Ridge, Cherokee Braves Mounted Infantry Photo

|