|

Strawberry

Plains and a Bridge over the Holston River during Civil War

On Feb. 27, 1894, an elderly feeble looking gentleman with one hand walked into

the offices of Dr. W. T. Delaney in Bristol. The man seemed to loathe his presence in the office, as he was

never one to take charity. The Tennessee legislature, however, had funded a pension for former Confederate

soldiers who had served the state during the war and, with age limiting the gentleman’s chance for employment, he had

no other choice. His wife had died and he was the sole guardian of three granddaughters. Then, as now, there were many "arm-chair"

warriors who claimed to be veterans, which led to the establishment of an interview process to ensure the men were who they

said and no one took advantage of the meager fund. Accompanying the aged applicant, however, were two solid witnesses in the

eyes of the doctor. One was a powerful man in state government and future governor Alfred Taylor. The other was also man of

prominence in the region named C. C. Frasier. A couple of weeks earlier a reporter from the Louisville Courier-Journal in

Kentucky, who had heard of the former Confederate’s story, tracked him down, did an interview, and encouraged the impoverished

man to seek a Confederate pension from Tennessee.

| Knoxville Civil War History |

|

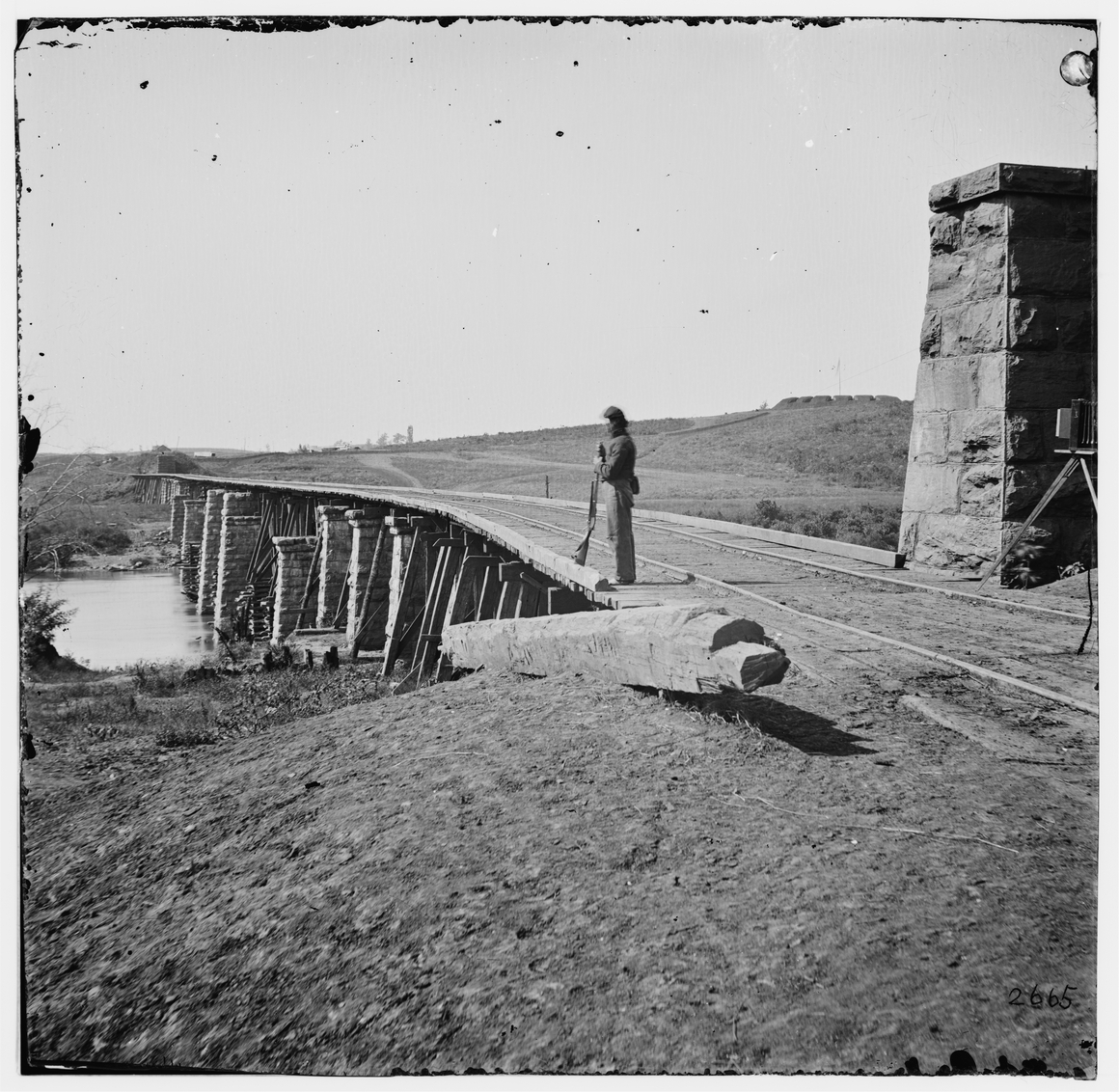

| Strawberry Plains Bridge, Tennessee |

(About) Title: Strawberry Plains Bridge, 20 miles northeast of Knoxville;

with camera on tripod at right. Creator: Barnard, George N., 1819-1902, photographer. Created 1863. Published 1864. Medium:

1 negative (2 plates) : glass, stereograph, wet collodion. Summary: Photograph of the War in the West. These photographs are

of the Siege of Knoxville, November-December 1863. The difficult strategic situation of the Federal armies after Chickamauga

enabled Bragg to detach a force under Longstreet which, although having the objective of forcing the Union army out of

East Tennessee, was able to push Burnside's force into bivouac in Knoxville, which he defended successfully. These views,

taken after Longstreet's withdrawal on December 3, include one of Strawberry Plains, which was on his line of retreat. Union

Army Record shows that Barnard was photographer of the chief engineer's office, Military Division of the Mississippi, and

his views were transmitted with the report of the chief engineer of Burnside's army, April 11, 1864. Reproduction Number:

LC-DIG-cwpb-02139 (digital file from original neg. of left half) LC-DIG-cwpb-02140 (digital file from original neg. of right

half) LC-B8171-2665 (b&w film neg.) Photograph was scanned for highest resolution by webmaster at Library of Congress,

and subsequently placed on the internet. Believed to be the highest resolution, highest quality photo of the event online.

Courtesy LOC.

| Strawberry Plains, Tennessee |

|

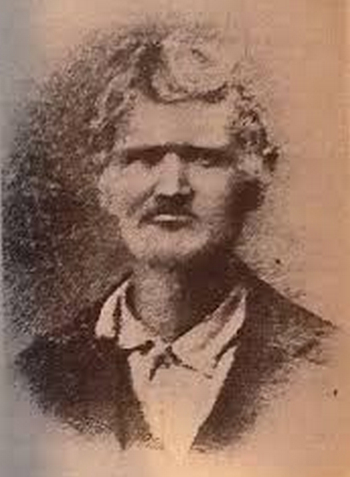

| James Keelan |

When Dr. W. T. Delaney pulled out the state pension forms

and began officially questioning the individual, he uncovered an incredible story that had been the stuff of campfire legends

since the war had ended – a story that would forever earn the man in front of him a place in American military history.

James Keelan was born in 1818 in Pittsylvania County, Va. His parents were descended from Scots-Irish immigrants and sustained

themselves through farming the rich lands of the region. They eventually migrated into upper East Tennessee and James Keelan helped his family on the farm never

receiving any formal education. Like most boys in Tennessee,

he grew up hunting and fishing in the region and was regarded as one of the best at it. He was also a first-rate farm hand

and scratched out an existence in East Tennessee.

When the War Between the States began and Tennessee voted to secede from the Union, 43-year-old

Keelan enlisted in the Will Thomas Legion as a Private. The Will Thomas Legion was unique in that it was made up of mostly

Cherokee and mountaineers. They were regarded as one of the Confederacy’s better units and fought hard in the Virginia campaigns before being called back to East Tennessee. The

Confederacy knew that they had to occupy valuable roads and passes such as the Cumberland Gap.

The Confederate occupation of the region, however, led

to pro-Union William B. Carter coming up with a plan he thought would give the region back to the Federals. His plan was for

the Union to mass a large body of soldiers on the Tennessee-Kentucky border ready to invade

East Tennessee. While they were gathering, he and a handful of men would slip into Confederate-held

East Tennessee and start disrupting communications and burning nine major railway bridges in the

region. From Bridgeport to Bristol,

Carter planned to down the bridges along with the telegraph lines while the Union Army, capitalizing on the confusion, swept

through Cumberland Gap and retook the region from the Confederacy. Carter would then rally

pro-Union East Tennesseans, who would join the invading force.

The plan was presented to President Lincoln, who approved

it and a date of Nov. 8, 1861 was selected by Union

Generals William Sherman and George Thomas, who would actually lead the invasion. While Thomas was a big believer in Carter’s

plan, Sherman didn’t like it and thought too much could go wrong. On Oct.

19, Carter left the Federal camp to enter East

Tennessee and start recruiting saboteurs

for the task. The Confederates were aware that something was going on near Cumberland Gap and intelligence reports were disconcerting. While Thomas’ men were still gathering, Confederate General Felix

Zollicoffer unexpectedly advanced through Cumberland

Gap towards London, KY with a small army. The move forced Thomas to start the campaign

early, which resulted in a vicious battle near Wild Cat that forced the Confederacy to withdraw. The surprising military action

by Zollicoffer shook up Sherman and forced him to order Thomas to halt his invasion into East Tennessee. It was too late to stop Carter and his saboteurs, who had already recruited men for the mission.

As expected, the saboteurs successfully struck as planned

on Nov. 8. The Unionists destroyed five railroad bridges – two on the East Tennessee and Virginia road, one on the East Tennessee and Georgia road, and two on the Western Atlantic road. One of the main targets left for Carter’s men was the Strawberry Plains Bridge, which spanned the Holston River above Knoxville and was being guarded by the Will Thomas Legion. On guard that night was 43-year-old Private James Keelan,

who was doing his best to fight the November chill the wind carried off of the river. Around 10 p.m., he heard a rider approaching and assumed his post to qualify the man. Keelan quickly identified him

as local Private, William W. Stringfield, who was on leave from the Confederacy’s First Tennessee Cavalry. Stringfield stopped for a moment and talked to Keelan.

The two men exchanged pleasantries and he rode on to his home where he longed for a warm fire and his own bed. Keelan watched

him go and climbed down to his post below the railroad bridge. The position was stationed behind some heavy timbers, which

allowed him to see what was coming without being see. He nestled back against the wall and prepared for a long, sleepless

night. Being an experienced woodsman, his mind knew which sounds to throw away and which were unusual to the night. The only

unusual sound he expected this evening, as most others since he had guarded the bridge, was the deafening noise of a train

passing overhead. Keelan was trying to warm himself when he heard a click of a horseshoe against stone. He stopped what he

was doing and strained his ears for the sound in the darkness. He knew that the pitch-black night would amplify not only sounds,

but his imagination and he stayed still to see if his mind was trying to play tricks on him. Through the darkness, Keelan

made out the sound of approaching boot steps. He listened and surmised it was a group of men and, judging by the sound of

the approaching steps, figured their number was close to a dozen.

Unknown to the solitary sentry, William C. Pickens and

nine other men had been recruited from Sevier County by Carter to burn the Strawberry Plains Bridge.

They crept along slowly towards the railroad bridge. If they were caught, they knew what would happen. Bridge-burners were

hated on both sides of the war and those caught, especially in civilian clothes, would be hanged with little questions asked.

They had heard the Will Thomas Legion was guarding the structure, but had not seen anyone on or near it and figured they had

the element of surprise. While seven men stood as lookouts, Pickens and another man named Montgomery started making their way to its most vulnerable point.

Keelan felt the first

knots of fear, but remained where he was listening and peering into the darkness to try and make out the approaching men.

His hand felt around the bunk for his rifle, but could not locate it. Instead, it fell upon his single-shot pistol and Keelan

quietly eased the hammer back and waited. Pickens climbed up the pier and struck a match lighting pine splinters. He stretched

forward to thrust them into the weatherboards on the bridge to ignite the dried wood that would start the destructive fire.

As he reached to place it, Keelan aimed his pistol inches away from his chest and fired. Pickens, who was killed instantly,

fell from his position onto the men below carrying the burning tinder with him. The other sentry posted on the far side was

never heard from and bolted from his post because of the superior numbers. The private didn’t have time to think about

it. He was used to relying on himself and, now that he had their attention, the private knew it was time to act.

Keelan fell back into his bunk as shots were fired at him

from the cursing men. He again groped in the darkness for his rifle, but couldn’t find it. His hand found his Bowie

knife and, with it and the butt of his spent pistol, Keelan moved away from his bunk and towards the attacking men, who were

climbing the bridge and firing at him. As the men made

his position, Keelan came under heavy attack. They slashed out at him with sabers and fired in his direction. As they moved

on him, Keelan held up his left hand to fend off the blows and swung his knife in a wide arch cutting anything that was near

him. It was brutal hand-to-hand combat and the blows were starting to have their effect on Keelan. One of the men suddenly

swung a saber at his head. Keelan saw it coming, ducked, and heard the blade cut deep into the timber. It was all the advantage

he needed. Keelan caught the man off balance and pulled him deep onto his blade. As he tossed the man from the bridge and

saw the others coming at him, Keelan knew he was in a fight for his life and viciously attacked the oncoming force. Twice

he drove them back and twice they moved again cursing him– angered that one man could be so hard to kill. Those knocked

from the bridge regained their rifles and shouted at the remaining men to back off so they could shoot "the damned rebel".

Shots smashed into the timbers above his head and three tore into Keelan’s flesh. Now badly hurt and tasting blood,

Keelan leapt at his oncoming attackers’ berserk with fury and swinging his knife. It found home on two attackers who

yelped in pain and fell from the bridge.

The men suddenly realized that lights were burning at the

Stringfield residence and knew it wouldn’t be long before Confederate reinforcements arrived. They tried to gather those

wounded they could and fled into the darkness. Keelan lay alone on the bridge bleeding badly and feeling weakness starting

to overtake him. He also saw the lights at the nearby house and started dragging himself towards it to give what he thought

would be his last report on his post. The years of hard labor and farming blessed him with a strong constitution and he managed

to stay conscious. The Tennessean drug himself inch by inch off of the bridge and towards the lights. He kept an incredible

presence of mind and, thinking that he was dying, didn’t stop at the Stringfield residence for fear of alarming the

women inside. Instead, he pulled himself past it to the Elmore residence. He found the gate and leaned against it where he

started calling for help from inside.

When William Elmore, unaware of what had just occurred,

reached Keelan, he couldn’t believe he was still alive and thought the worst.

"Jim," said Elmore, "you’ve

been drunk or asleep and let the train run over you."

"No Billy," was Keelan’s reply. "They have killed me, but I

saved the bridge."

Elmore and Stringfield awakened Dr. Sneed, who was the closest doctor to come and tend the Keelan’s

wounds. The dedicated physician worked throughout the night to save the Confederate. The doctor treated three severe saber

cuts to Keelan’s scalp, a gunshot wound in the right hand, right arm, and an inoperable bullet in the left hip. Keelan’s

left hand, however, was the worst. The doctor saw it was only hanging by a sliver of flesh and told him it was lost. He offered

to remove it and stitch the stump. Keelan told him to just stitch the wound as he could rest his rifle against the stump.

The next morning Confederate investigators went to

the scene of the gruesome fight. There they found the bodies of three men. One was shot and two others slashed to death. From

what they could tell from the evidence, blood, and horse hooves, another six or seven had gotten away badly cut and injured.

After Keelan’s wounds healed, he rejoined the Will Thomas Legion and, with one hand, fought to the end of the War Between

the States being discharged in Bristol, Tenn.

For the next thirty years, Keelan scratched out an existence

working odd jobs, cutting wood, and farming while he was able. The 76-year-old man had reached a point where he could no longer

perform the tasks where he could make a living and now was forced to take what he considered "charity" from the state.

Dr. W. T. Delaney continued filling out the form as the

old man recanted the battle where he had sustained his wounds all those years ago. He asked the final questions on the form

to Keelan:

"How did you get out of the Army?"

"I was discharged," replied Keelan.

"Did you take the oath of allegiance

to the United States Government?"

"Yes."

"If so, when and under what circumstances?"

"A short time after the war

closed at Bristol, Tenn., under

compulsion," was Keelan’s reply.

Delaney then asked Alfred Taylor and C. C. Frasier if they could verify this account

and they both nodded yes. The doctor pushed the form across the desk where Keelan made his "X" under the date of the petition.

The

next week a Bristol Law Court Deputy Clerk named Brewer accepted the application and pulled out another form for Taylor and

Frasier to sign onto verifying Keelan’s service in the Confederate Army. At the bottom of the form the Deputy Clerk,

who had known Keelan throughout his life, wrote:

"He was a brave and good soldier and the act performed by him, at the

time he received the wound mentioned in his deposition, was one of the most heroic acts performed by any one during the late

civil war..."

Keelan’s application was approved and the small pension

kept him from suffering the disgrace of having to enter the poorhouse. On Feb. 12, 1895, a year after his remarkable story had been made public, James Keelan passed away in Bristol. Those who knew him lay their beloved friend and hero in Bristol’s East Ridge Cemetery. On the headstone erected at his grave, they carved a Confederate battleflag with

the words. "James Keelan, Defender of the Bridge –

The South’s Horatius."

On Aug. 20, 1994, James Keelan became the 40th Confederate soldier to receive the Confederate Medal of Honor. He would

be one of six Tennesseans to be posthumously awarded the medal. It is on permanent display at Confederate Memorial Hall in

Knoxville, which is managed by the local chapter of the United Daughters

of the Confederacy.

Keelan’s service that night in Strawberry Plains

forever earned him the title Horatius of the South among soldiers of the Will Thomas Legion and those who knew of him. According

to accounts by ancient Roman historians Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Horatius Cocles (translated as meaning "one-eyed")

was a member of the Roman militia in 494 BC guarding the Sublician Bridge over the Tiber River when the Etruscan invader Lars Porsena seized a Roman position and started a charge

towards his position. The Roman Army broke under the pressure and fled across the bridge leaving Horatius by himself to face

the advancing Etruscans. Horatius managed to stop some of the more seasoned soldiers and with, an impassioned speech telling

them sure disaster would follow if they deserted their post, he inspired the small Roman unit to start tearing down the bridge

while he tried to hold off the Etruscans. The people thought he was insane, but the soldiers went to work while Horatius walked

towards the enemy. Seeing the single soldier, the Etruscans pulled up short of the bridge thinking the Romans had laid a trap.

Horatius walked along the bridge cursing the invaders and challenging the soldiers to single combat. He defeated everyone

sent against him and created such a fury among the Etruscan command that they slung spears, rocks, and other missiles towards

him, which he repelled with his shield. Badly wounded and bleeding, his Roman compatriots yelled and Horatius noticed they

were fleeing from the bridge. When the Etruscans pushed towards the bridge, the injured Horatius leapt into the Tiber River in full armor. As the bridge began its collapse, everyone on both

sides of the river watched and waited to see if he would perish in the raging waters. Horatius broke the water, however, and

swam to the Roman shore eliciting cheers as much from the enemy warriors as his own soldiers. It is said during the battle

he lost his eye and, thus, earned his name. He was one of Rome’s

most celebrated heroes and a statue was erected near the bridge to commemorate the action. His name became synonymous with

individual courage under fire. Keelan is the only known individual in American history to have ever earned such an accolade.

Following his actions on the bridge and subsequent medical

attention, it is said that the Stringfield ladies wrapped his severed hand and buried it in Jefferson County – although the site has never been found. The place where

the action took place can still be seen in Strawberry Plains. Although much heavier battle action would later occur in Knoxville and nearby Grainger County, the incident at the Strawberry Plains Railroad Bridge would become the most famous action in the region that occurred during the War Between

the States. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer’s check of the Union forces at Cumberland Gap was

successful, but cost the general his life in a nearby skirmish. It would be two years before the Union forces took East Tennessee.

Source: tennesseehistory.com

Recommended Reading: Bridge Burners: A True Adventure of East Tennessee Underground Civil War.

Description: When the East Tennessee and Virginia Railway line was completed, dignitaries

gathered in celebration as the final spike was hammered into the last tie in Greene

County. Opening new doors of growth and economic development in the Region,

the railroad would become a point of conflict only three years later. When the Civil War began, the line became a vital link

in transporting Confederate troops and supplies into Virginia.

Continued below...

The railroad

was vulnerable since many hostile Unionists remained in the region. Confederate authorities were understandably worried about

the rail lines and how to protect them. Inevitably the stage was set and on a cold Friday night, November 8, 1861, the Unionists

proceeded with plans to burn the key railroad bridges of East Tennessee; President Abraham Lincoln had approved the plan. This thoroughly researched,

easy-to-read narrative tells the incredible true story of the people and events in the ‘insurrection gone wrong’.

Recommended

Reading: Mountain Rebels: East Tennessee

Confederates and the Civil War, 1860-1870 (240 pages) (University

of Tennessee Press). Description:

In this fine study, Groce points out that the Confederates in East Tennessee suffered more for the ‘Southern Cause’

than did most other southerners. From the first rumblings of secession to the redemption of Tennessee

in 1870, Groce introduces his readers to numerous men and women from this region who gave their all for Southern

Independence. He also points out that East Tennesseans were divided in their

loyalties and that slavery played only a small role. Groce goes too great lengths to expose the vile treatment of the Region’s

defeated Confederates during the Reconstruction. Numerous maps, pictures, and tables underscore the research.

Recommended Reading: Valor

in Gray: The Recipients of the Confederate Medal of Honor. Description: Gregg

Clemmer writes in detail about the events that occurred that caused these men to be remembered. He has spent countless hours

researching the character of each recipient and their heroic-selfless actions. Whether a descendant of the North or the South,

this book will make you feel the emotion that drove these men to risk their lives for their values and beliefs. Each chapter

is devoted to a separate Confederate Medal of Honor recipient. Valor in Gray is destined to be one of the best books on Civil

War history.

Recommended

Reading:

Confederate Industry: Manufacturers And Quartermasters in the Civil War (412

pages) (University Press of Mississippi: September 2005). Description: For those

with an interest in the Civil War, this book gives new insight into the efforts of the Confederacy to keep its armies in the

field during four years of Union onslaughts. Harold Wilson, an English professor at Old

Dominion University, looks largely

at the textile industry but also focuses on armaments and other production. Continued below...

He also discusses

the Confederacy's efforts to supply itself from Europe with blockade-running ships, and the efforts of Northern armies - especially

under Sherman - to destroy the Confederacy's industrial base.

He examines the rise of Southern industry in the decades after the war. This

is a solid, well-researched book that covers an important area of Civil War history in unprecedented depth.

Recommended Reading:

Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive Chase and the First Medal of Honor. Description: "The Great Locomotive Chase has been the stuff of legend and

the darling of Hollywood. Now we have a solid history of the

Andrews Raid. Russell S. Bonds’ stirring account makes clear why the raid failed and what happened to the raiders."—James

M. McPherson, author of Battle Cry of Freedom, winner of the Pulitzer Prize. Continued below...

On April 12, 1862 -- one year to the day after Confederate

guns opened on Fort Sumter -- a tall, mysterious smuggler and self-appointed Union spy named James J. Andrews and nineteen

infantry volunteers infiltrated north Georgia and stole a steam engine referred to as

the General. Racing northward at speeds approaching sixty miles an hour, cutting telegraph lines and destroying track

along the way, Andrews planned to open East Tennessee to the Union army, cutting off men and materiel from the Confederate

forces in Virginia. If they succeeded, Andrews and his raiders could change the course of the war. But the General’s

young conductor, William A. Fuller, chased the stolen train first on foot, then by handcar, and finally aboard another engine,

the Texas. He pursued the

General until, running out of wood and water, Andrews and his men abandoned the doomed locomotive, ending the adventure that

would soon be famous as The Great Locomotive Chase, but not the ordeal of the soldiers involved. In the days that followed,

the "engine thieves" were hunted down and captured. Eight were tried and executed as spies, including Andrews. Eight others

made a daring escape to freedom, including two assisted by a network of slaves and Union sympathizers. For their actions,

before a personal audience with President Abraham Lincoln, six of the raiders became the first men in American history to

be awarded the Medal of Honor -- the nation's highest decoration for gallantry. Americans north and south, both at the time

and ever since, have been astounded and fascinated by this daring raid. Until now, there has not been a complete history of

the entire episode and the fates of all those involved. Based on eyewitness accounts, as well as correspondence, diaries,

military records, newspaper reports, deposition testimony and other primary sources, Stealing the General: The Great Locomotive

Chase and the First Medal of Honor by Russell S. Bonds is a blend of meticulous research and compelling narrative that is

destined to become the definitive history of "the boldest adventure of the war."

Recommended

Reading: Let Us Die Like Brave Men: Behind The Dying Words Of Confederate Warriors (Hardcover). Description: This book offers over 50 dramatic, bittersweet

accounts of the last moments and words of Southern soldiers (some famous, others virtually unknown) from the rank of general

to private. Photographs of the soldiers, their graves, or the places where they fell illustrate the text. Each story was chosen

to highlight a different aspect of the war, and every state of the Confederacy is represented by soldiers whose poignant stories

are told here. Continued below…

About the Author:

Daniel W. Barefoot is the author of 9 previous books, including General Robert F. Hoke: Lee's Modest Warrior. He is a former

N.C. state representative who lives in Lincolnton, North Carolina.

|