|

First Battle of Manassas: 1st Battle of Manassas

1st Battle of Manassas, Virginia

Other Names: 1st Battle of Bull Run

Location: Fairfax County and Prince William County

Campaign: Manassas Campaign (July 1861)

Date(s): July 21, 1861

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell [US]; Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston and Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard [CS]

Forces Engaged: 60,680 total (US 28,450; CS 32,230)

Estimated Casualties: 4,700 total (US 2,950; CS 1,750)

Result(s): Confederate victory

| First Battle of Manassas |

|

| 1st Battle of Bull Run |

Setting the Stage: The

First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas (the name used by Confederate forces), was fought on July 21, 1861,

in Prince William County, Virginia, near the city of Manassas, not far from Washington, D.C. It was the first major battle

of the American Civil War. The Union forces were slow in positioning themselves, allowing Confederate reinforcements time

to arrive by rail. Each side had about 18,000 poorly trained and poorly led troops in their first battle. It was a Confederate

victory followed by a disorganized retreat of the Union forces.

Just months after the start of the war at Fort Sumter, the Northern public

clamored for a march against the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, which they expected to bring an early end to the

rebellion. Yielding to political pressure, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell led his unseasoned Union Army across Bull Run against

the equally inexperienced Confederate Army of Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard camped near Manassas Junction. McDowell's ambitious

plan for a surprise flank attack on the Confederate left was poorly executed by his officers and men; nevertheless, the Confederates,

who had been planning to attack the Union left flank, found themselves at an initial disadvantage.

Confederate reinforcements under Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston arrived from

the Shenandoah Valley by railroad and the course of the battle quickly changed. A brigade of Virginians under the relatively

unknown brigadier general from the Virginia Military Institute, Thomas J. Jackson, stood their ground and Jackson received

his famous nickname, "Stonewall Jackson". The Confederates launched a strong counterattack, and as the Union troops began

withdrawing under fire, many panicked and the retreat turned into a rout. McDowell's men frantically ran without order in

the direction of Washington, D.C. Both armies were sobered by the fierce fighting and many casualties, and realized the war

was going to be much longer and bloodier than either had anticipated.

Description: This was the first major land battle of the armies

in Virginia. On July 16, 1861, the untried Union army under Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell marched from Washington against

the Confederate army, which was drawn up behind Bull Run beyond Centreville. On the 21st, McDowell crossed at Sudley Ford

and attacked the Confederate left flank on Matthews Hill. Fighting raged throughout the day as Confederate forces were driven

back to Henry Hill. Late in the afternoon, Confederate reinforcements (one brigade arriving by rail from the Shenandoah

Valley) extended and broke the Union right flank. The Federal retreat rapidly deteriorated into a rout. Although victorious,

Confederate forces were too disorganized to pursue. Confederate Gen. Bee and Col. Bartow were killed. Thomas J. Jackson earned the nom de guerre "Stonewall." By July 22, the shattered Union army reached the safety of Washington. This battle

convinced the Lincoln administration that the war would be a long and costly affair (see: Battle of First Manassas: A Major Turning Point?). McDowell was relieved of command of the Union army and replaced by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who set about reorganizing

and training the troops.

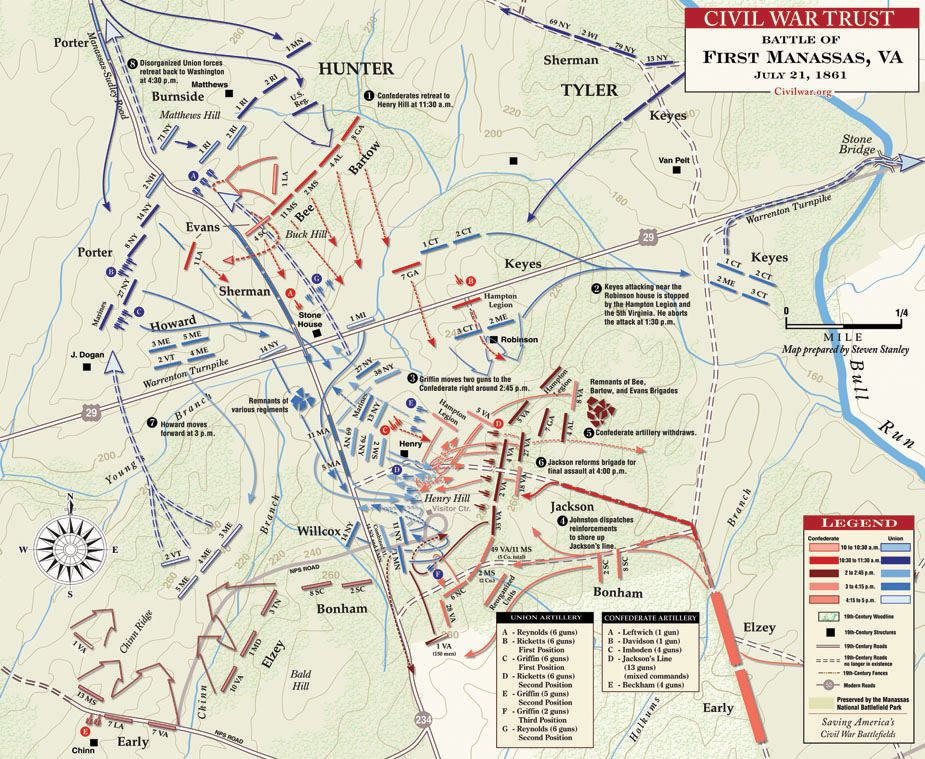

| 1st Battle of Manassas Map |

|

| Civil War First Battle of Manassas Map |

Battle: On the morning of July 21 1861, McDowell sent the

divisions of Hunter and Heintzelman (about 12,000 men) from Centreville at 2:30 a.m., marching southwest on the Warrenton

Turnpike and then turning northwest toward Sudley Springs. Tyler's division (about 8,000) marched directly toward the Stone

Bridge. The inexperienced units immediately developed logistical problems. Tyler's division blocked the advance of the main

flanking column on the turnpike. The later units found the approach roads to Sudley Springs were inadequate, little more than

a cart path in some places, and did not begin fording Bull Run until 9:30 a.m. Tyler's men reached the Stone Bridge around

6 a.m.

At 5:15 a.m., Richardson's brigade fired a few artillery rounds across Mitchell's

Ford on the Confederate right, some of which hit Beauregard's headquarters in the Wilmer McLean house as he was eating breakfast,

alerting him to the fact that his offensive battle plan had been preempted. Nevertheless, he ordered demonstration attacks

north toward the Union left at Centreville. Bungled orders and poor communications prevented their execution. Although he

intended for Brig. Gen. Richard S. Ewell to lead the attack, Ewell, at Union Mills Ford, was simply ordered to "hold ... in

readiness to advance at a moment's notice." Brig. Gen. D.R. Jones was supposed to attack in support of Ewell, but found himself

moving forward alone. Holmes was also supposed to support, but received no orders at all.

All that stood in the path of the 20,000 Union soldiers converging on

the Confederate left flank were Col. Nathan "Shanks" Evans and his reduced brigade of 1,100 men. Evans had moved some of his

men to intercept the direct threat from Tyler at the bridge, but he began to suspect that the weak attacks from the Union

brigade of Brig. Gen. Robert C. Schenck were merely feints. He was informed of the main Union flanking movement through Sudley

Springs by Captain Edward Porter Alexander, Beauregard's signal officer, observing from 8 miles southwest on Signal Hill.

In the first use of wig-wag semaphore signaling in combat, Alexander sent the message "Look out for your left, your position

is turned."

Evans hastily led 900 of his men from their position fronting the Stone

Bridge to a new location on the slopes of Matthews Hill, a low rise to the northwest of his previous position. The Confederate

delaying action on Matthews Hill included a spoiling attack launched by Major Roberdeau Wheat's 1st Louisiana Special Battalion,

"Wheat's Tigers". After Wheat's command was thrown back, and Wheat seriously wounded, Evans received reinforcement from two

other brigades under Brig. Gen. Barnard Bee and Col. Francis S. Bartow, bringing the force on the flank to 2,800 men.They

successfully slowed Hunter's lead brigade (Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside) in its attempts to ford Bull Run and advance across

Young's Branch, at the northern end of Henry House Hill. One of Tyler's brigade commanders, Col. William T. Sherman, crossed

at an unguarded ford and struck the right flank of the Confederate defenders. This surprise attack, coupled with pressure

from Burnside and Maj. George Sykes, collapsed the Confederate line shortly after 11:30 a.m., sending them in a disorderly

retreat to Henry House Hill.

As they retreated from their Matthews Hill position, the remainder of Evans's,

Bee's, and Bartow's commands received some cover from Capt. John D. Imboden and his battery of four 6-pounder guns, who held

off the Union advance while the Confederates attempted to regroup on Henry House Hill. They were met by generals Johnston

and Beauregard, who had just arrived from Johnston's headquarters at the M. Lewis Farm, "Portici".

Fortunately for the Confederates, McDowell did not press his advantage and

attempt to seize the strategic ground immediately, choosing to bombard the hill with the batteries of Capts. James B. Ricketts

(Battery I, 1st U.S. Artillery) and Charles Griffin (Battery D, 5th U.S.) from Dogan's Ridge.

Brig. Gen Thomas J. Jackson's Virginia brigade came up in support of the

disorganized Confederates around noon, accompanied by Col. Wade Hampton and his Hampton's Legion, and Col. J.E.B. Stuart's

cavalry. Jackson posted his five regiments on the reverse slope of the hill, where they were shielded from direct fire, and

was able to assemble 13 guns for the defensive line, which he posted on the crest of the hill; as the guns fired, their recoil

moved them down the reverse slope, where they could be safely reloaded. Meanwhile, McDowell ordered the batteries of Ricketts

and Griffin to move from Dogan's Ridge to the hill for close infantry support. Their 11 guns engaged in a fierce artillery

duel across 300 yards against Jackson's 13. Unlike many engagements in the Civil War, here the Confederate artillery had an

advantage. The Union pieces were now within range of the Confederate smoothbores and the predominantly rifled pieces on the

Union side were not effective weapons at such close ranges, with many shots fired over the head of their targets.

One of the casualties of the artillery fire was Judith Carter Henry, an

85-year-old widow and invalid, who was unable to leave her bedroom in the Henry House. As Ricketts began receiving rifle fire,

he concluded that it was coming from the Henry House and turned his guns on the building. A shell that crashed through the

bedroom wall tore off one of the widow's feet and inflicted multiple injuries, from which she died later that day.

"The Enemy are driving us," Bee exclaimed to Jackson.

Jackson, a former U.S. Army officer and professor at the Virginia Military Institute, is said to have replied, "Then, Sir,

we will give them the bayonet!" Bee exhorted his own troops to re-form by shouting, "There is Jackson standing like a stone

wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Rally behind the Virginians!"

This exclamation was the source for Jackson's (and his brigade's) nickname,

"Stonewall". There is, but was not during the war, some controversy over Bee's statement and intent, which could not

be clarified because he was mortally wounded almost immediately after speaking and none of his subordinate officers wrote

reports of the battle. Major Burnett Rhett, chief of staff to General Johnston, claimed that Bee was angry at Jackson's failure

to come immediately to the relief of Bee's and Bartow's brigades while they were under heavy pressure. Those who subscribe

to this opinion believe that Bee's statement was meant to be pejorative: "Look at Jackson standing there like a stone wall!"

But the argument can be put to rest on the following facts alone: Thomas Jackson already had a reputation as a tenacious,

aggressive soldier, because he had been commended for bravery during several battles, earning two brevet promotions, in

the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). After First Bull Run, many Union commanders would highly respect and even

fear the Confederate, particularly during Jackson's Valley Campaign where his much smaller force continued to thrash

three larger Union armies, and the men who served under the former VMI professor

would continue to speak and write wonderful paragraphs describing Jackson's superior leadership during battle.

Artillery commander Griffin decided to move two of his guns to the southern

end of his line, hoping to provide enfilade fire against the Confederates. At approximately 3 p.m., these guns were overrun

by the 33rd Virginia, whose men were outfitted in blue uniforms, causing Griffin's commander, Maj. William F. Barry, to mistake

them for Union troops and to order Griffin not to fire on them. Close range volleys from the 33rd Virginia and Stuart's cavalry

attack against the flank of the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Ellsworth's Fire Zouaves), which was supporting

the battery, killed many of the gunners and scattered the infantry. Capitalizing on this success, Jackson ordered two regiments

to charge Ricketts's guns and they were captured as well. As additional Federal infantry engaged, the guns changed hands several

times.

The capture of the Union guns turned

the tide of battle. Although McDowell had brought 15 regiments into the fight on the hill, outnumbering the Confederates two

to one, no more than two were ever engaged simultaneously. Jackson continued to press his attacks, telling soldiers of the

4th Virginia Infantry, "Reserve your fire until they come within 50 yards! Then fire and give them the bayonet! And when you

charge, yell like furies!" For the first time, Union troops heard the disturbing sound of the Rebel yell. At about

4 p.m., the last Union troops were pushed off Henry House Hill by a charge of two regiments from Col. Philip St. George Cocke's

brigade.

To the west, Chinn Ridge had been occupied by Col. Oliver O. Howard's brigade

from Heintzelman's division. Also at 4 p.m., two Confederate brigades that had just arrived from the Shenandoah Valley—Col.

Jubal A. Early's and Brig. Gen. Kirby Smith's (commanded by Col. Arnold Elzey after Smith was wounded)—crushed Howard's

brigade. Beauregard ordered his entire line forward. McDowell's force crumbled and began to retreat.

The retreat was relatively orderly up to the Bull Run crossings, but it

was poorly managed by the Union officers. A Union wagon was overturned by artillery fire on a bridge spanning Cub Run Creek

and incited panic in McDowell's force. As the soldiers streamed uncontrollably toward Centreville, discarding their arms and

equipment, McDowell ordered Col. Dixon S. Miles's division to act as a rear guard, but it was impossible to rally the army

short of Washington. In the disorder that followed, hundreds of Union troops were taken prisoner. Expecting an easy Union

victory, the wealthy elite of nearby Washington, including congressmen and their families, had come to picnic and watch the

battle. When the Union army was driven back in a running disorder, the roads back to Washington were blocked by panicked civilians

attempting to flee in their carriages.

Since their combined army had been

left highly disorganized as well, Beauregard and Johnston did not fully press their advantage, despite urging from

Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who had arrived on the battlefield to see the Union soldiers retreating. An attempt

by Johnston to intercept the Union troops from his right flank, using the brigades of Brig. Gens. Milledge L. Bonham and James

Longstreet, was a failure. The two commanders squabbled with each other and when Bonham's men received some artillery fire

from the Union rear guard, and found that Richardson's brigade blocked the road to Centreville, he called off the pursuit.

Aftermath: Bull

Run was the largest and bloodiest battle in American history up to that point. Union casualties were 460 killed, 1,124 wounded,

and 1,312 missing or captured; Confederate casualties were 387 killed, 1,582 wounded, and 13 missing. Among the Union dead

was Col. James Cameron, brother of President Lincoln's first Secretary of War, Simon Cameron. Among the Confederate casualties

was Col. Francis S. Bartow, who was the first Confederate brigade commander to be killed in the Civil War. General Bee was

mortally wounded and died the following day.

Union forces and civilians alike feared that Confederate forces would advance

on Washington, D.C., with very little standing in their way. On July 24, Prof. Thaddeus S. C. Lowe ascended in the balloon

Enterprise to observe the Confederates moving in and about Manassas Junction and Fairfax. He saw no evidence of massing Rebel

forces, but was forced to land in Confederate territory. It was overnight before he was rescued and could report to headquarters.

He reported that his observations "restored confidence" to the Union commanders.

The Northern public was shocked at the unexpected defeat of their army when

an easy victory had been widely anticipated. Both sides quickly came to realize the war would be longer and more brutal than

they had imagined. On July 22 President Lincoln signed a bill that provided for the enlistment of another 500,000 men for

up to three years of service. On July 25, eleven thousand Pennsylvanians who had earlier been rejected by the U.S. Secretary

of War, Simon Cameron, for federal service in either Patterson's or McDowell's command arrived in Washington, D.C., and were

finally accepted.

The reaction in the Confederacy was more muted. There was little public

celebration as the Southerners realized that despite their victory, the greater battles that would inevitably come would mean

greater losses for their side as well.

Beauregard was considered the hero of the battle and was promoted that day

by President Davis to full general in the Confederate Army. Stonewall Jackson, arguably the most important tactical contributor

to the victory, received no special recognition, but would later achieve glory for his 1862 Valley Campaign. Privately, Davis

credited Greenhow with ensuring Confederate victory. Jordan sent a telegram to Greenhow: "Our President and our General direct

me to thank you. We rely upon you for further information. The Confederacy owes you a debt. (Signed) JORDON, Adjutant-General."

Irvin McDowell bore the brunt of the blame for the Union defeat and was

soon replaced by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who was named general-in-chief of all the Union armies. McDowell was also

present to bear significant blame for the defeat of Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia by Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of

Northern Virginia thirteen months later, at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Patterson was also removed from command.

The name of the battle has caused controversy since 1861. The Union Army

frequently named battles after significant rivers and creeks that played a role in the fighting; the Confederates generally

used the names of nearby towns or farms. The U.S. National Park Service uses the Confederate name for its national battlefield

park, but the Union name (Bull Run) also has widespread currency in popular literature.

Battlefield confusion between the battle flags, especially the similarity

of the Confederacy's "Stars and Bars" and the Union's "Stars and Stripes" when fluttering, led to the adoption of the Confederate

Battle Flag, which eventually became the most popular symbol of the Confederacy and the South in general.

During the American Civil War, the North generally named a battle

after the closest river, stream or creek and the South tended to name battles after towns or railroad junctions. Hence the

Confederate name Manassas after Manassas Junction, and the Union name Bull Run for the stream Bull Run.

Sources: National Park Service, Civil War Trust, Library of Congress.

Advance to:

|