|

Mason–Dixon

Line History Homepage

| Mason-Dixon Line History |

|

| Mason-Dixon Line Marker |

Introduction

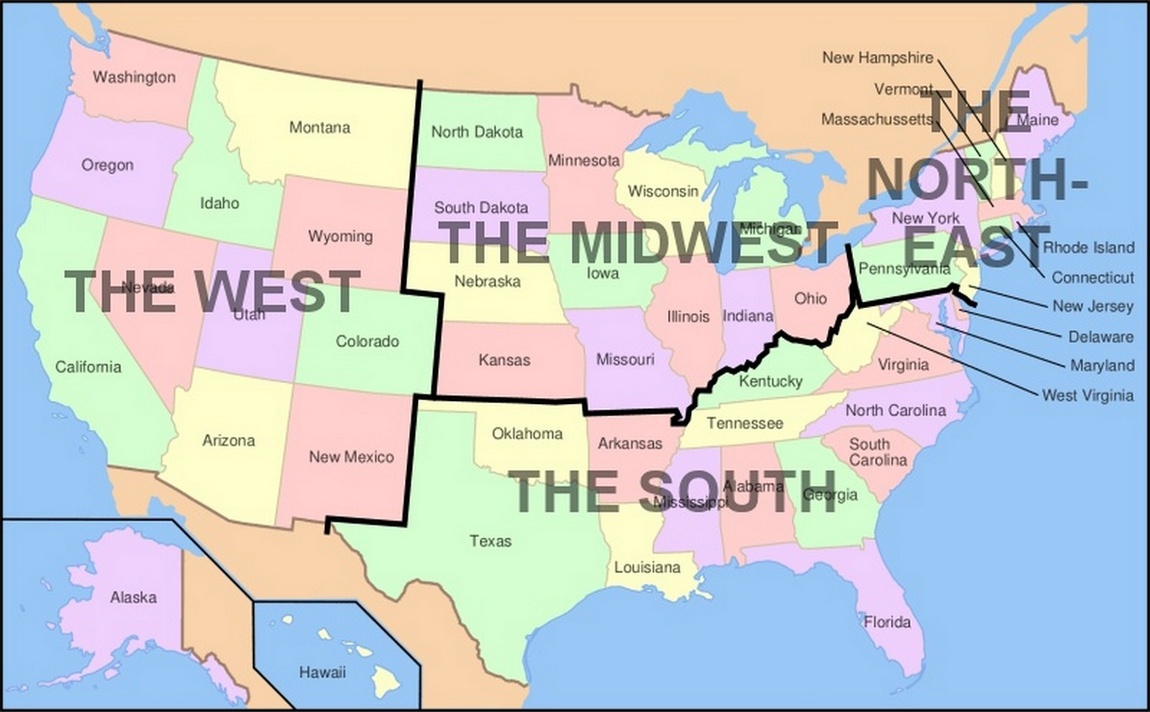

Rebel, Yankee, Northerner, Southerner, and American culture all

come to mind when we hear someone discuss the famous Mason-Dixon Line. What exactly is the Mason and Dixon Line and

why was it created in the first place? Does the Mason-Dixon Line really separate the North and South? These are just some

of the questions that are discussed on the Mason-Dixon Line History page. The lesson also answers many of the common questions about

the line as well as some lesser known facts and trivia. This study will allow the student to know precisely where the

Mason-Dixon Line is located, which states are included in the Mason and Dixon Line, why it is called and named the Mason-Dixon

Line, and not the Dixon-Mason Line, and some of the political and cultural differences between the nation's

Northern and Southern states of the historic mark. While a simple yet crude Mason-Dixon Line map shows the basic geography,

the current states and their relationship to the line, other maps have been enlarged to give the Mason and Dixon Line its

significance to the nation as a whole. Lastly, have borders of the line changed, if so how and why?

Summary

The Mason–Dixon Line, or Mason and Dixon's Line, is a demarcation

line between four U.S. states, forming part of the borders of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia (then part

of Virginia). It was surveyed between 1763 and 1767 by Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon in the resolution of a border dispute

between British colonies in Colonial America. Since the first official usage of the term "Mason and Dixon Line" during congressional

debates over the Missouri Compromise of 1820, popular speech continues to reference the Mason-Dixon Line

symbolically as a cultural, political, and social boundary, or dividing line between the Northern and Southern United

States. From Mason-Dixon comes the term "Dixie," a

name applied to states south of the line, which historically are the Southern states. Politically, the Mason-Dixon

Line has long since served as the dividing line between the red and blue states, meaning the dominant line separating the

nation's Republicans and Democrats. Leading up to the American Civil War, the Mason-Dixon Line was the nation's sectional

boundary separating Northern and Southern states, or the North and South, by sectionalism. During the American Civil War (1861-1865), citizens residing in states north of the line were referred to as

Yankees while persons south of the line were called Rebels. Immediately

following the war, the Mason and Dixon Line was quoted as a cultural, social, and political boundary. Presently,

while the Mason-Dixon Line, or Mason-Dixon, remains the nation's expository boundary separating the North and South,

it represents the bisection of continuing sectional differences in political and social ideologies.

| The original Mason-Dixon Line |

|

| Original Mason-Dixon Line Map |

Purpose

The Penn and Calvert families had hired Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon,

English surveyors, to settle their dispute over the boundary between their two proprietary colonies of Pennsylvania and Maryland.

Definition

The Mason and Dixon Line, commonly called the Mason-Dixon Line,

was originally the boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland.

In the 1800s the Mason-Dixon Line became symbolic of the nation's division between the "free states" and

"slave states" from the Missouri Compromise of 1820 until the end of the American Civil War in 1865. Although Pennsylvania

abolished slavery before the end of the American Revolution, Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri, also known as

Border States, remained slave states until the end of the war. Historically, the Mason-Dixon Line served to settle

a border dispute between the Penn and Calvert families, but today the boundary simply illustrates sectional differences

between North and South, Northerner and Southerner, as the diverging social, cultural, and political .

First Usage

The first usage of the term "Mason and Dixon Line" was the political coinage

of "Mason-Dixon Line" in the congressional debates over the bill known as the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which

sought to define the northern limit of the slave-owning states.

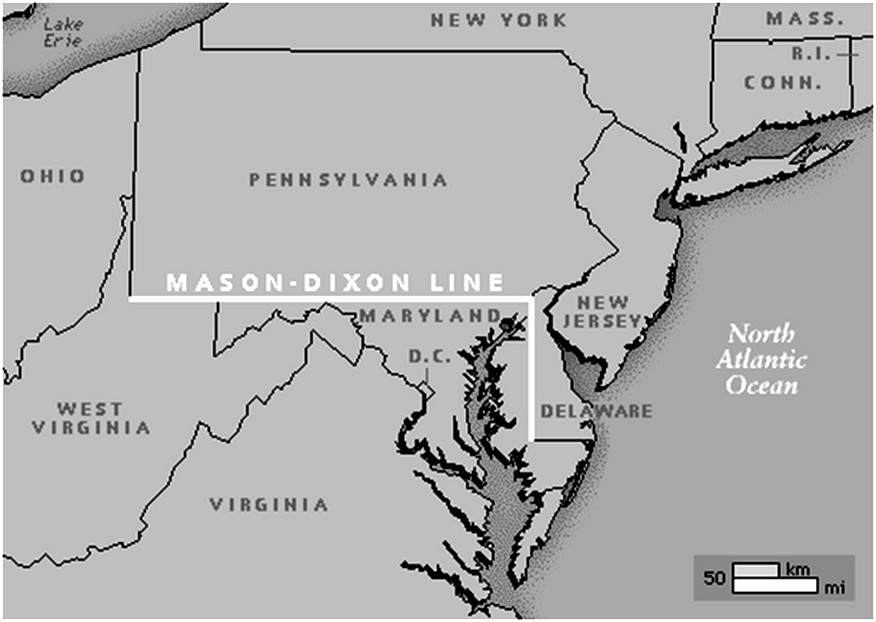

| Mason-Dixon Line Map, aka Mason and Dixon Line Map |

|

| Mason-Dixon Line Map. Enhanced to Scale Map. Mason-Dixon Line History Lesson. |

History

From 1763 to 1767, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon surveyed and marked most

of the boundaries between Maryland, Pennsylvania and the Three Lower Counties that became Delaware. The survey, which would

be known as the Mason and Dixon Line, or Mason-Dixon Line, was commissioned by the Penn family of Pennsylvania and

Calvert family of Maryland to settle their long-running boundary dispute.

After the Civil War, the line continued to be considered a cultural boundary. Some

have viewed the Mason-Dixon Line continuing westward from Pennsylvania down the Ohio River to the Mississippi River, and crossing the Mississippi to place Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas south of the line.

Debate whether Border States such as Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland and West Virginia belong on the north or south side of this boundary line continues

to this day. A common assumption of the split between Northern and Southern U.S. lies between Virginia and West Virginia,

however. Maryland and Pennsylvania both claimed the land between the 39th and 40th parallels according to the charters granted

to each colony. The 'Three Lower Counties' (Delaware) along Delaware Bay moved into the Penn sphere of settlement, and later

became the Delaware Colony, a satellite of Pennsylvania.

In 1732 the proprietary governor of Maryland, Charles Calvert, 5th

Baron Baltimore, signed an agreement with William Penn's sons which drew a line somewhere in between, and also renounced the

Calvert claim to Delaware. But later, Lord Baltimore claimed that the document he signed did not contain the terms he had agreed to, and

refused to put the agreement into effect. Beginning in the mid-1730s, violence erupted between settlers claiming various loyalties

to Maryland and Pennsylvania. The border conflict between Pennsylvania and Maryland would be known as Cresap's War. The issue

was unresolved until the Crown intervened in 1760, ordering Frederick Calvert, 6th Baron Baltimore to accept the 1732 agreement.

As part of the settlement, the Penns and Calverts commissioned the English team of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon

to survey the newly established boundaries between the Province of Pennsylvania, the Province of Maryland, Delaware Colony

and parts of Colony and Old Dominion of Virginia.

| Mason-Dixon Line History |

|

| Mason-Dixon Line Historical Marker |

The issue was unresolved until the Crown intervened in 1760, ordering Frederick

Calvert, 6th Baron Baltimore to accept the 1732 agreement. As part of the settlement, the Penns and Calverts commissioned

the English team of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon to survey the newly established boundaries between the Province

of Pennsylvania, the Province of Maryland, Delaware Colony and parts of Colony and Old Dominion of Virginia. After Pennsylvania

abolished slavery in 1781, the western part of this line and the Ohio River became a border between free and slave states,

although Delaware remained a slave state.

Mason and Dixon's actual survey line began to the south of Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, and extended from a benchmark east to the Delaware River and west to what was then the boundary with western

Virginia. The surveyors also fixed the boundary between Delaware and Pennsylvania and the approximately north–south

portion of the boundary between Delaware and Maryland. Most of the Delaware–Pennsylvania boundary is a circular arc,

and the Delaware–Maryland boundary does not run truly north-south because it was intended to bisect the Delmarva Peninsula

rather than follow a meridian.

The Maryland–Pennsylvania boundary is an east-west line with approximate

mean latitude of 39° 43' 20" N (Datum WGS 84). In reality, the east-west Mason-Dixon Line is not a true line in the geometric

sense, but is instead a series of many adjoining lines, following a path between latitude 39° 43' 15" N and 39° 43' 23" N;

a surveyor or mapper might call it an approximate rhumb line. As such, the line approximates a segment of a small circle upon

the surface of the (also approximately) spherical Earth. An observer standing on such a line and viewing its path toward an

unobstructed horizon, would perceive it to bend away from his line of sight, an effect of the inequality between the amount

of curvature to his left and right. Among parallels of latitude, only the Equator is a great circle and would not exhibit

this effect.

The surveyors also extended the boundary line to run or extend between

Pennsylvania and colonial western Virginia, which became West Virginia after the American Civil War, though this was contrary

to their original charter; this extension of the line was only confirmed later. The Mason–Dixon Line was marked by

stones every mile and ”crownstones” every five miles, using stone shipped from England. The Maryland side says

(M) and the Delaware and Pennsylvania sides say (P). Crownstones include the two coats-of-arms. Today, while a number of the

original stones are missing or buried, many are still visible, resting on public land and protected by iron cages. Mason and

Dixon confirmed earlier survey work which delineated Delaware's southern boundary from the Atlantic Ocean to the ”Middle

Point” stone (along what is today known as the Transpeninsular Line). They proceeded nearly due north from this to the

Pennsylvania border.

| US Census Bureau Mason-Dixon Line Map of Boundary |

|

| Mason-Dixon Line Map. US Census Bureau Map of Boundaries. |

The Mason–Dixon Line is comprised of four segments corresponding to the terms of the settlement: Tangent

Line, North Line, Arc Line, and 39° 43' N parallel. The most difficult task was fixing the Tangent Line, as they had to confirm

the accuracy of the Transpeninsular Line mid-point and the Twelve-Mile Circle, determine the tangent point along the circle,

then actually survey and monument the border. They then surveyed the North and Arc Lines.

They performed this work between 1763 and 1767, and this actually left a small wedge of land in dispute between

Delaware and Pennsylvania until 1921.

In April 1765, Mason and

Dixon began their survey of the more famous Maryland-Pennsylvania line. They were commissioned to run it for a distance of

five degrees of longitude west from the Delaware River, fixing the western boundary of Pennsylvania. But in October

1767 at Dunkard Creek near Mount Morris, Pennsylvania, nearly 244 miles west of the Delaware, their Iroquois guides had reached

the border of the Lenape, an enemy, and forced them to halt their progress. On

October 11, they made their final observations at 233 miles from their starting point. In 1784, surveyors David Rittenhouse

and Andrew Ellicott and their crew completed the survey of the Mason-Dixon Line to the southwest corner of Pennsylvania, five

degrees from the Delaware River. Other surveyors continued west to the Ohio River. The section of the line between

the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania and the river is the county line between Marshall and Wetzel counties, West Virginia.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 created the political conditions which

made the Mason-Dixon Line important to the history of slavery. It was during the Congressional debates leading up

to the compromise that the term "Mason-Dixon Line" was first used to designate the entire boundary between free states and

slave states.

The boundary between Pennsylvania and Maryland has been resurveyed three times: in 1849, 1900, and

in the 1960s. On November 14, 1963, during the bicentennial of the Mason–Dixon

Line, U.S. President John F. Kennedy opened a newly completed section of Interstate 95 where it crossed the Maryland-Delaware

border. It was his last public appearance, because 8 days later in Dallas, Texas, he was assassinated. The Delaware Turnpike

and the Maryland portion of the new road were each later designated as the John F. Kennedy Memorial Highway.

| Original Mason-Dixon Line Map |

|

| Mason-Dixon Line Map, aka Mason and Dixon Line. US History. |

Conclusion

One hundred years after Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon began their monumental

effort to chart the boundary, American soldiers from opposite sides of the line fought and died on the fields of

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in what would become the final and fatal attempt of the Southern states to breach the Mason-Dixon

Line during the American Civil War (1861-1865). Although the guns of the conflict have long since been silenced and the

participants of both sides have been buried, citizens continue to remember, commemorate, and even debate the Civil War.

And while Americans still can't agree on the causes and origins of the war or even the name of the conflict itself, the

Mason-Dixon Line remains and it continues to be celebrated in music, television, and literature.

(Sources and related reading below.)

Recommended Reading:

A House Divided: Sectionalism and Civil War, 1848-1865

(The American Moment). Reviews: "The best short treatment

of the sectional conflict and Civil War available... Sewell convincingly demonstrates that the conflict was a revolutionary

experience that fundamentally transformed the Republic and its people, and left a racial heritage that still confronts America today. The result is a poignant discussion of the

central tragedy of American history and its legacy for the nation." -- William E. Gienapp, Georgia Historical Quarterly. "A provocative starting point for discussion, further

study, and independent assessment." -- William H. Pease, History. "Sewell's style is fast moving and very readable... An excellent

volume summarizing the stormy period prior to the war as well as a look at the military and home fronts." -- Civil War Book

Exchange and Collector's Newsletter. Continued below…

"A well-written,

traditional, and brief narrative of the period from the end of the Mexican War to the conclusion of the Civil War... Shows

the value of traditional political history which is too often ignored in our rush to reconstruct the social texture of society."

-- Thomas D. Morris, Civil War History. "Tailored for adoption in college courses. Students will find that the author has

a keen eye for vivid quotations, giving his prose welcome immediacy." -- Daniel W. Crofts, Journal of Southern History.

Recommended

Reading: CAUSES

OF THE CIVIL WAR: The Political, Cultural, Economic and Territorial Disputes Between the North and South. Description: While South Carolina's

preemptive strike on Fort Sumter and Lincoln's subsequent call to arms started the Civil War, South Carolina's

secession and Lincoln's military actions were simply the last

in a chain of events stretching as far back as 1619. Increasing moral conflicts and political debates over slavery-exacerbated

by the inequities inherent between an established agricultural society and a growing industrial one-led to a fierce sectionalism

which manifested itself through cultural, economic, political and territorial disputes. Continued below...

This historical study reduces sectionalism to its most fundamental form, examining the underlying source

of this antagonistic climate. From protective tariffs to the expansionist agenda, it illustrates the ways in which the foremost

issues of the time influenced relations between the North and the South.

Recommended

Reading: Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right (Critical Issue Book). From Booklist:

In this concise essay, Stephanson explores the religious antecedents to America's

quest to control a continent and then an empire. He interprets the two competing definitions of destiny that sprang from the

Puritans' millenarian view toward the wilderness they settled (and natives they expelled). Here was the God-given chance to

redeem the Christian world, and that sense of a special world-historical role and opportunity has never deserted the American

national self-regard. But would that role be realized in an exemplary fashion, with America

a model for liberty, or through expansionist means to create what Jefferson called "the empire

of liberty"? Continued below…

The antagonism

bubbles in two periods Stephanson examines closely, the 1840s and 1890s. In those times, the journalists, intellectuals, and

presidents he quotes wrestled with America's purpose in fighting each decade's war, which added

territory and peoples that somehow had to be reconciled with the predestined future. …A sophisticated analysis of American

exceptionalism for ruminators on the country's purpose in the world.

Recommended

Reading: Seizing Destiny: The Relentless Expansion of American Territory. Publishers

Weekly: In an admirable and important addition to his

distinguished oeuvre, Pulitzer Prize–winner Kluger (Ashes to Ashes, a history of the tobacco wars) focuses on the darker

side of America's rapid expansion westward. He begins with European settlement of the so-called New World, explaining that

Britain's successful colonization depended

not so much on conquest of or friendship with the Indians, but on encouraging emigration. Kluger then fruitfully situates

the American Revolution as part of the story of expansion: the Founding Fathers based their bid for independence on assertions

about the expanse of American virgin earth and after the war that very land became the new country's main economic resource.

Continued below...

The heart of

the book, not surprisingly, covers the 19th century, lingering in detail over such well-known episodes as the Louisiana Purchase

and William Seward's acquisition of Alaska. The final chapter looks at expansion in the 20th century. Kluger

provocatively suggests that, compared with western European powers, the United States

engaged in relatively little global colonization, because the closing of the western frontier sated America's expansionist hunger. Each chapter of this long, absorbing book is rewarding

as Kluger meets the high standard set by his earlier work. Includes 10 detailed maps.

Recommended Reading:

The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861

(Paperback), by David M. Potter. Review: Professor

Potter treats an incredibly complicated and misinterpreted time period with unparalleled objectivity and insight. Potter masterfully

explains the climatic events that led to Southern secession – a greatly divided nation – and the Civil War: the social, political

and ideological conflicts; culture; American expansionism, sectionalism and popular sovereignty; economic and tariff

systems; and slavery. In other words, Potter places under the microscope the root causes

and origins of the Civil War. He conveys the subjects in easy to understand language to edify the reader's

understanding (it's not like reading some dry old history book). Delving

beyond surface meanings and interpretations, this book analyzes not only the history, but the historiography of the time period

as well. Continued below…

Professor Potter

rejects the historian's tendency to review the period with all the benefits of hindsight. He simply traces the events, allowing

the reader a step-by-step walk through time, the various views, and contemplates the interpretations of contemporaries and

other historians. Potter then moves forward with his analysis. The Impending Crisis is the absolute gold-standard of historical

writing… This simply is the book by which, not only other antebellum era books, but all history books should be judged.

Sources: Cope, Thomas D. 1949. Degrees along the west line,

the parallel between Maryland and Pennsylvania. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 93 (May 1949); Cummings,

Hubertis Maurice, 1962. The Mason and Dixon line, story for a bicentenary, 1763-1963. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

Dept. of Internal Affairs, Harrisburg, PA.; Danson, Edwin, 2001 Drawing the line : How Mason and Dixon surveyed the

most famous border in America. John Wiley & Sons, New York; Ecenbarger, William, 2000. Walkin' the line:

a journey from past to present along the Mason-Dixon. M. Evans, New York; Latrobe, John H. B. 1882. The

history of Mason and Dixon's line: contained in an address, delivered by John H. B. Latrobe of Maryland, before the Historical

society of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1854. G. Bower, Oakland, DE.; Mason, A.H. (ed.) Journal of Charles Mason [1728-1786]

and Jeremiah Dixon [1733-1779]. 1969. Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society vol. 76). American Philosophical

Society, Philadelphia; Nathan, Roger E. 2000. East of the Mason-Dixon Line: a history of the Delaware boundaries.

Delaware Heritage Press, Wilmington, DE.; Pynchon, Thomas. 1997. Mason & Dixon. Henry Holt, New York;

Sobel, Dava. 1996. Longitude: the true story of a lone genius who solved the greatest scientific problem of his

time. Walker & Co., New York; The Federal and State Constitutions Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the

States, Territories, and Colonies Now or Heretofore Forming the United States of America, Compiled and Edited Under the Act

of Congress of June 30, 1906 by Francis Newton Thorpe, Washington, DC : Government Printing Office, 1909.

|