|

Appomattox County History

| Location of Appomattox, Virginia |

|

| Appomattox, Virginia, Map |

| Appomattox County History |

|

| Appomattox County Virginia History |

Growth

and Decline of Appomattox Court House

The county of Appomattox was born in 1845 when Buckingham, Campbell, Charlotte, and Prince Edward

counties were divided. Citizens who lived in the hinterlands of the aforementioned counties had been discouraged by the great

distance to the seats of the large counties. Of course, distance hampered their ability to vote and conduct other business,

and thus after the application of sufficient pressure, the state authorized the formation of Appomattox County. The fledgling jurisdiction

would take its' name from the stream whose headwaters emanated therein - - the Appomattox River.

The river itself was named after one of the villages of Chief Powhatans' Confederacy, known in the 1600s as Appomattoc, and

being located at the mouth of the river.

The small community of Clover Hill, with a population of fewer than one hundred,

was named as the county seat for Appomattox and was officially

made a town. Previously, it had been a mere stage stop along the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road. Most of the activity in Clover

Hill centered on the tavern, which provided lodging to travelers and fresh horses for the stage line since its construction

in 1819. Much of the Clover Hill area had been owned by Hugh Raine, until he sold the property to Colonel Samuel D. McDearmon.

Col. McDearmon, upon acquiring the land, had thirty acres surveyed for the town with two acres to be used by the county to

build a courthouse and other official buildings. The courthouse was to be built across the Stage Road from the Clover Hill

Tavern with the jail nearby. McDearmon divided the remaining land surrounding the courthouse into acre lots, feeling that

with Clover Hills' new status as a county seat he would find lawyers and tradesmen anxious to trade cash for deeds.

Into the 1850s, the growth of the town seemed imminent. Since most county seats in

Virginia by then were called 'Court Houses', the name of

the town was changed to Appomattox Court House. The

growing village boasted two stores, numerous law offices, a saddler, wheelwright, three blacksmiths, and other miscellaneous

businesses. Another tavern had been built by John Raine in 1848. This would later become the home of the Wilmer McLean family and would be used for the surrender meeting between Generals Lee and Grant on April 9,

1865.

The growth of the town was ultimately hampered by the very thing that gave most towns

life: the railroad. In 1854, a section of the railroad from Petersburg was extended from Farmville

to Appomattox Depot, three miles west of the county seat.

Eventually, the line extended to Lynchburg. The railroad was

too far from the town, so many businesses moved to the depot area where commerce was more lucrative. About this time stages

stopped running, and following the Civil War the Clover Hill area continued in decline.

In 1892, the courthouse burned down in what is believed to have been a chimney fire.

Influential citizens of the county decided to transfer the County

Government to the Depot, where many businesses had already relocated.

By 1894, the Depot had become the county seat and the name was changed to Appomattox.

Commerce

and Society

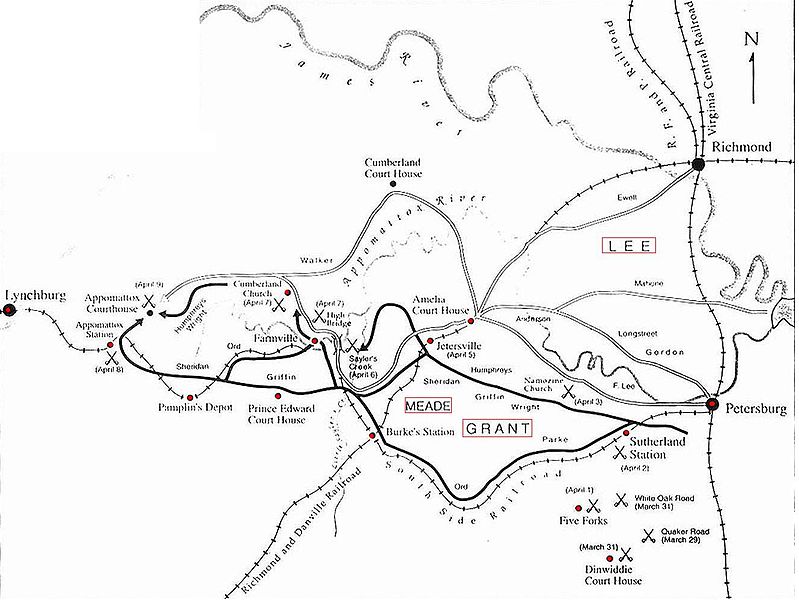

| Civil War Appomattox Virginia Campaign Map |

|

| Battles fought in and around Appomattox |

| Civil War Appomattox Campaign History |

|

| Appomattox County History |

The population of the county declined during the decade of the 1850s.

The U.S. census shows that in 1850 there were 9,193 people living in the county, but

in 1860 the populace was 8,889. Despite the declension of the population, the county fared quite well economically. The output

of tobacco almost doubled from 964,100 pounds in 1850 to 1,777,355 pounds in 1860. The cash value of farms increased from

$1,008,889 to $1,902,558. These increases reflected the benefit of the railroad to the local farmers, as well as the more

traditional means of transportation, such as the James River and Kanawha

Canal.

Wages changed with the constant economic flux. In 1850, the daily wage

for a laborer (with bed and board) was 25 cents. By 1860, the average worker's salary had doubled to 50 cents a day. A skilled

laborer -- such as a carpenter -- had a wage increase from 62 cents a day to one dollar (without board).

By 1870, the economic boom of the late antebellum era had reached an

abrupt halt. Tobacco output dropped to 656,944 pounds. The labor intensive leaf crop that had spurred the boom was also greatly

responsible for the development of the slave labor system in Virginia

and was notorious for robbing the soil of nutrients. Local farmers were forced to increase production of corn, oats, and wheat

(which had previously been grown on a much smaller scale than tobacco.)

Industry, however, was growing dramatically during these years. In 1850

there were only ten industries operating in the county. By 1870, the number had grown to fifty-three, employing 167 people.

The annual industrial production value reached $158,530 -- a pittance compared to the money the tobacco trade had once brought

in, but a start at diversification none the less.

The centers of social activity in the county, as in much of the south,

were the churches. In the mid-1800s, the county had twenty-four churches, mostly Baptist. The large Scotch-Irish population

of the area founded a number of Presbyterian churches. Ministers were quite often the school teachers too, so there was a

close tie between churches and education.

With the formation of the county, "Court Day" was established as the

first Thursday after the first Monday of each month and was quite a social event. Civil and criminal cases provided entertainment

for spectators. Auctions of cattle and slaves were held next to the courthouse, and farmers set up stands where produce such

as corn, apples, peaches, and figs could be purchased. Sometimes, political speeches would be given. On occasion, the men

of the local militia could display their soldierly bearing while marching around the town.

Over the years Senators, Congressmen, judges, attorneys, and musicians

have all called Appomattox County

their home, but the county has produced only a handful of people who would rise to national prominence. Prior to the war Thomas

Bocock was a U. S. Congressman, and would

become the only Speaker of the Confederate Congress. Joel and Sam Sweeney were noted musicians. Joel performed for Queen Victoria and popularized banjo playing in the United States

and Europe. Sam was a violin and banjo player during the Civil War -- playing for cavalry

General J.E.B. Stuart. Joel died in 1860 and Sam in 1864.

Blacks

in Appomattox County

The black population of Appomattox

County saw dramatic changes in their lives during the 1800s. In 1860,

there were 4,600 slaves and 171 freedmen living in the county, accounting for more than 53% of the total population. There

were about thirty black households. One family, the Humbles, was so large that they created a small settlement between the

Court House and the Depot.

Prior to the Civil War, the major fear for Virginia slaves was to be

sold and sent further south to what was referred to as "cotton country". During times of good crops, few slaves were sold,

but if times were bad, there was an increase in slave sales. Most blacks stayed in the county after the war -- evidenced in

the 1870 census -- which shows the black population at 4,536. Many freedmen worked as servants. Others were farmers owning

land, or tradesmen with their own businesses (such as blacksmiths, shoemakers, wheelwrights, and coopers).

Before the Civil War, educating blacks was illegal. By October 1866,

though, a few black schools were opening in the county. Near the Court House was Plymouth

Rock School House. By 1870 the

county boasted a black man certified to teach, William V. James.

In 1871, records indicate 352 black students attending six schools.

After World War I, Mrs. Mozella Jordan Price became supervisor of black schools and is credited with making many improvements.

Under her administration, buildings and teachers were added, and salaries increased for educators.

The first permanent black church building was Galilee, built around 1913,

with several more quickly following: Mt. Airy, Jordan,

Mt. Obed,

Promised Land, and others.

Appomattox County in the 1990s

The population of the county has remained largely stagnant since the 1860s,

increasing less than 34% in 140 years. The silver lining is that the slow growth has done much to preserve the sylvan setting

for the reunification of a war torn country. The 1990 census shows a population of about 12,300 -- with the greatest increase

occurring since 1970. Schools are now integrated; churches flourish; small businesses abound. Due to the establishment of

Appomattox Court House National Historical Park on the site of the surrender, the county sees a large influx of tourists,

especially during the summer months.

Sources: National

Park Service; Appomattox Court

House National Historic

Park; Civil War Trust (located online Civilwar.org)

Try the Search Engine for Related Studies: Appomattox Court House National

Historic Park History of Appomattox County Court House Virginia Founders Growth Economy Commerce Demographics Facts American

Civil War Photos Pictures Photographs

|