|

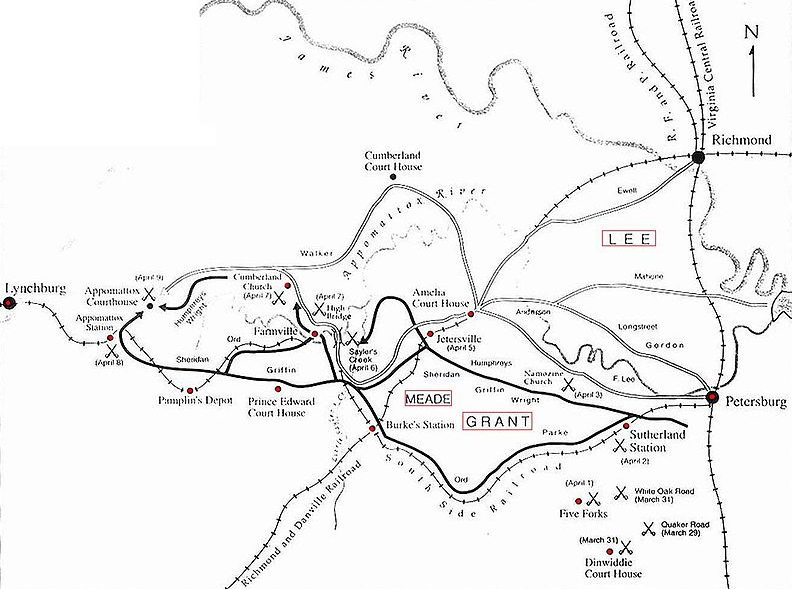

THE APPOMATTOX CAMPAIGN: March 29 - April 9, 1865

Appomattox Campaign [March-April 1865]

| Appomattox Campaign Battlefield Map |

|

| Civil War Appomattox Campaign Map |

What was to become the final campaign for Richmond began when the Federal Army of

the Potomac crossed the James River in June 1864. Under Lieutenant General U. S. Grant's

command, Federal troops applied constant pressure to the Confederate lines around Richmond

and Petersburg, during the Siege of Petersburg, and by autumn, three of the four railroads into Petersburg

had been cut. The South Side Railroad remained as the only means of rail transportation into Confederate lines, and once severed,

the Army of Northern Virginia would have no other choice but to evacuate the capitol.

However, Lee's concern stretched beyond the Confederate capitol to Federal

actions elsewhere in the south. By February of 1865, two federal armies, one under Major General William T. Sherman and the

other under Major General John M. Schofield, were moving through the Carolinas. If not stopped,

they could sever Virginia from the rest of the south, and if they joined Grant at Petersburg, Lee's men would face four armies instead of two.

Realizing the danger, Lee wrote the Confederate Secretary of War on

February 8, 1865: "You must not be surprised if calamity befalls us." By the time he wrote this letter, Lee

knew he would have to leave the Petersburg lines, the only

question was when. Muddy roads and the poor condition of the horses forced the Confederates to remain in the trenches throughout

March.

| Appomattox Campaign Map |

|

| Civil War Appomattox Campaign Map |

Once again, Ulysses S. Grant seized the initiative. On March 29, Major

General Philip H. Sheridan's cavalry and the V Corps began moving southwest toward the Confederate right flank and the South

Side Railroad. On the 1st of April, 21,000 Federal troops smashed the 11,000 man Confederate force under Major General George

Pickett at an important road junction known locally as Five Forks. Grant followed up this victory with an all - out offensive against Confederate

lines on April 2nd.

With his supply lines cut, Lee had no choice but to order Richmond and Petersburg evacuated on

the night of April 2-3. Moving by previously determined routes, Confederate columns left the trenches that they had occupied

for ten months. Their immediate objective was Amelia Court House where forces from Richmond

and Petersburg would concentrate and receive rations sent from Richmond. Once his army was reassembled, Lee planned to march down the line of the Richmond and Danville Railroad with the hope of meeting General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee

coming from North Carolina. Together, the two Confederate

armies could establish a defensive line near the Roanoke River, and assume the offensive against Sherman.

The march from Richmond and Petersburg started well enough. Many of the Confederates, including

Lee, seemed exhilarated at being in the field once again, but after the first day's march signs of weariness and hunger began

to appear. When Lee reached Amelia Court House on April 4, he found, to his dismay that the rations for his men had not arrived.

Although a rapid march was crucial, the hungry men of the Army of Northern Virginia needed supplies. While awaiting the arrival

of troops from Richmond, delayed by flood conditions, Lee

decided to halt the march and send wagons into the countryside to gather provisions. Local farmers had little to give and

the wagons returned practically empty.

The major result of this delay at Amelia was a lost day of

marching which allowed the pursuing Federals time to catch up. Amelia proved to be the turning point of the

campaign.

Leaving Amelia Court House on April 5, the columns of Lee's army had

traveled only a few miles before they found Union cavalry and infantry squarely across their line of march - through Jetersville

and on toward Danville and Johnston's Army.

| Appomattox Campaign Map |

|

| Battles of Appomattox Campaign Map |

Rather than attack the entrenched federal position, Lee changed his

plan. He would march his army west, around the Federals, and attempt to supply his troops at Farmville along the route of

the South Side railroad. The retreat of the Army of Northern Virginia was under constant Federal pressure. Union cavalry attacked

the Confederate wagon train at Paineville destroying a large number of wagons. Tired from lack of sleep (Lee had ordered night

marches to regain the day he lost) and hungry, the men began falling out of the column, or broke ranks searching for food.

Mules and horses collapsed under their loads.

As the retreating columns became more ragged, gaps developed in the

line of march. At Sailor's Creek (a few miles east of Farmville), Union cavalry exploited such a gap to block two Confederate

corps under Lt. Generals Richard Anderson and Richard Ewell until the much larger Union VI Corps arrived to crush them.

Watching the debacle from a nearby hill, Lee exclaimed, "My God!

Has the army been dissolved?" Nearly 8,000 men and 8 generals were lost in one stroke; either killed, captured, or

wounded. The remnants of the Army of Northern Virginia arrived in Farmville on April 7 where rations awaited them, but the

Union forces followed so quickly that the Confederate cavalry had to make a stand in the streets of the town to allow their

fellow troops to escape and most Confederates never received the much needed rations.

Blocked once again by Grant's army, Lee once more swung west hoping

that he could be supplied farther down the rail line and then turn south. Just north of Farmville, Lee turned west onto the

Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road. The Union II and VI Corps followed. Unbeknownst to Lee, however, the Federal cavalry and the

V, XXIV, and XXV Corps were moving along shorter roads south of the Appomattox River to cut him off. While in Farmville on April 7, Grant sent a letter to

Lee asking for the surrender of his army. Lee, in the vicinity of Cumberland

Church, received the letter and read it. He then handed it to one of

his most trusted corps commanders -- Lt. General James Longstreet. Longstreet tersely replied, "Not yet."

As Lee continued his march westward he knew the desperate situation his army faced. If he could reach Appomattox Station before

the Federal troops he could receive rations sent from Lynchburg and then make his way to Danville via Campbell Court House (Rustburg) and Pittsylvania

County. If not, he would have no choice but to surrender.

On the afternoon of April 8, the Confederate columns halted a mile northeast

of Appomattox Court House. That night, artillery fire could be heard from Appomattox Station, and the red glow, to the west, from

Union campfires foretold that the end was near. Federal cavalry and the Army of the James -- marching on shorter roads --

had blocked the way south and west. Lee consulted with his generals and determined that one more attempt should be made to

reach the railroad and escape.

At dawn on April 9, General John B. Gordon's Corps attacked the Union

cavalry blocking the stage road, but after an initial success, Gordon sent word to Lee around 8:30 a.m. "... my command

has been fought to a frazzle, and unless Longstreet can unite in the movement, or prevent these forces from coming upon my

rear, I cannot go forward." Receiving the message, Lee replied, "There is nothing left for me to do but

to go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths." (See Appomattox Campaign.)

Sources: National

Park Service; Appomattox Court

House National Historic

Park

Try the Search Engine for Related Studies: The Appomattox Campaign Virginia Battle of Appomattox Court House

General Robert E Lee Army of Northern Virginia General US Grant Army of the Potomac Pictures Surrender Terms Conditions History

Photos

|