|

|

Civil War Infantry

Union and Confederate Army

Civil War Military

Infantry Organization, Weapons, Tactics, Battle Formation, and Battles

Introduction

During the American Civil War (1861-1865), artillery, infantry, and

cavalry were each assigned to the Army. While the Civil War infantry was associated with the army, and army was

often interchanged with infantry, officially the Civil War Army organization composed primarily infantry, cavalry, and artillery.

The Infantry in the Civil War comprised foot-soldiers who fought primarily

with small arms,

and they carried the brunt of the fighting on battlefields across the United States. While the smoothbore musket had

an accurate range of 50-100 yards, in 1861 it had been replaced with the rifled-musket which had the capability

of striking its target from 300 to 600 yards in the hands of a skilled soldier. Napoleonic

Tactics advanced the army into line of battle at

distances of 50-100 yards from the opposing force. Subsequently commands were issued by the commanders

for volleys to be exchanged, thus causing mass casualties. Many Union and Confederate soldiers

were taught the outdated Napoleonic Tactics from West Point, and they continued to apply the tactics while

using the latest lethal weapons on the Civil War battlefield.

As the Civil War progressed,

battlefield tactics evolved too slowly in response to the new form of warfare being waged in America.

The use of military balloons, rifled-muskets, rifled-artillery, repeating rifles, and fortified entrenchments contributed

to the death of many men. Generals and other officers, many professionally trained in tactics from the Napoleonic Wars, nevertheless, failed

to adapt new tactics while employing modern weapons.

| Napoleonic Tactics resulted in mass casualties |

|

| These dead soldiers at Gettysburg were a result of obsolete tactics being greeted by modern rifles. |

The smallest fighting

unit for the infantry during the Civil War was the company. Companies generally consisted of 100 men on paper but were

seldom up to strength due to casualties and illnesses. The staff of a company comprised of a Captain, who commanded, a 1st

Lieutenant, 2nd Lieutenant and two Sergeants, and several Corporals. While the company was the smallest unit, it would at

times be split up into platoons, sections, and squads, but not for extended periods of time and rarely, if ever, acting as

independent commands.

Infantry companies were banded together with other companies

to form battalions or regiments. Generally, there were eight companies to a battalion and ten companies to a regiment (the

Union sometimes used twelve) and were designated with letters from the alphabet such as "A", "B", "C", "D", etc. (The letter

"J" was not used because when shouted in battle it could easily be misunderstood for the letter "A" and when written it

looked too much like the letter "I".) Companies often carried the name of the individual or individuals who organized the

company or for the place from where they came. For example, Company "M" of the second Florida Infantry Regiment was also known

as the Howell Guards or the Dennison Guard from Ohio, organized at Camp Dennison. The staff of a regiment included a Colonel

who commanded, a Lieutenant Colonel, Major, 1st Lieutenant (acted as an Adjutant), a surgeon, Assistant Surgeon, Quartermaster,

Commissary Officer, and a Sergeant Major. The regiment was the primary fighting force for both the Union and the Confederacy.

Regiments were usually grouped together with other regiments

to form a brigade. Brigades were commanded by a Brigadier General, and usually, but not always, regiments from the same state

were brigaded together. Confederate Brigades were generally known by the name of the Brigadier General who commanded it, such

as Wilcox's Brigade. Wilcox's Brigade was commanded by Cadmus M. Wilcox and was comprised of the 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, and

14th Alabama Infantry Regiments. Union Brigades were usually numbered.

When several brigades were grouped together, they formed a division.

Major Generals led divisions with Confederate divisions being named for the general who commanded it, such as Cheatham's Division

in the Army of Tennessee during the Atlanta Campaign. Union divisions were numbered with Roman numerals.

When several divisions were organized together, they formed

a corps. A corps was commanded by a Lieutenant General and could operate independently or operate as part of the larger army,

which was their usual role. Like other large Confederate units, Confederate corps were named for their commander, such as

Longstreet's Corps. Union Corps were numbered as were the rest of military organizations, except for Armies.

Armies were the largest of all the fighting units during the

Civil War and were composed of corps, divisions, brigades, and regiments and included artillery, cavalry, signal corps, and

various other units. A Lieutenant General or a General generally led armies.

| Civil War Infantry Chart |

|

| Civil War Army and Infantry Structure |

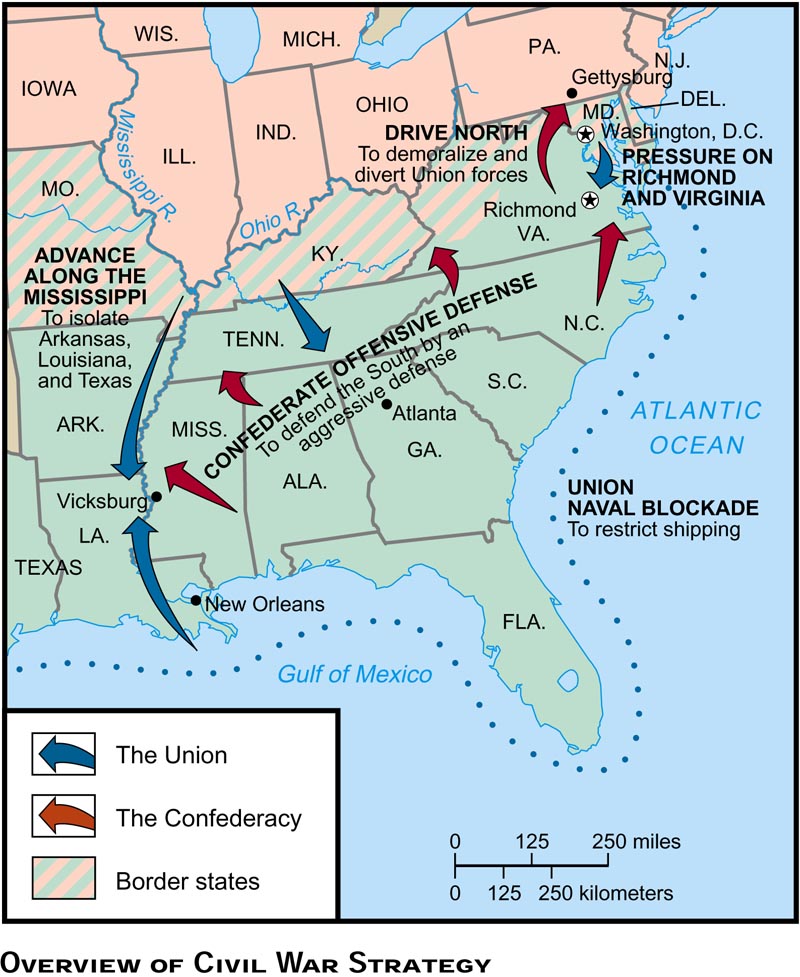

| Civil War Strategy and Tactics Map |

|

| Union and Confederate Strategy Map |

History

At the beginning of the Civil War, the United States Army

consisted of merely 16,000 men of all branches, with infantry representing the vast majority of this total. Some of these

infantrymen had seen considerable combat experience in the Mexican-American War, as well as in the West in various encounters,

including the Utah War and several campaigns against Indians. However, the majority spent their time on garrison or fatigue

duty. In general, the majority of the infantry officers were graduates of military schools such as the United States Military

Academy.

In some cases, individual states, such as New York, had previously

organized formal militia infantry regiments, originally to fight Indians in many cases, but by 1861, they existed mostly for

social camaraderie and parades. These organizations were more prevalent in the South, where hundreds of small local militia

companies existed.

With the secession of eleven Southern states by early 1861 following

the election of President Abraham Lincoln, tens of thousands of Southern men flocked to hastily organized companies, which

were soon formed into regiments, brigades, and small armies, forming the genesis of the Confederate States Army. Lincoln responded

to secession by issuing an initial call for 75,000 volunteers, with subsequent quotas for each state, to put down

the rebellion, and the Northern states responded. The resulting forces came to be known as the Volunteer Army (even though

they were paid), versus the Regular Army. Infantry comprised over 80% of the manpower in these forces.

Hardee's writings about military tactics were widely used on

both sides in the conflict. William Joseph Hardee (October 12, 1815 –

November 6, 1873) was a career U.S. Army officer, serving during the Second Seminole War and fighting in the Mexican-American

War. He served as a Confederate general during the American Civil War.

At West Point, Hardee served as a tactics instructor and as

commandant of cadets from 1856 to 1860. In 1855 at the behest of U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, Hardee published Rifle

and Light Infantry Tactics for the Exercise and Manoeuvres of Troops When Acting as Light Infantry or Riflemen, popularly

known as Hardee's Tactics, which became the best-known drill manual of the Civil War. He is also said to have designed

the so-called Hardee hat during this time.

Hardee resigned his U.S. Army commission on January 31, 1861,

after his home state of Georgia seceded from the Union. He joined the Confederate States Army as a colonel and on October

10, 1862, he was appointed one of the first of only eighteen Confederate lieutenant generals.

Infantry Organization

The typical infantry regiment of the early Civil War consisted of 10 companies

(each with exactly 100 men, according to Hardee's 1855 manual, and led by a captain, with associated lieutenants). Field officers

normally included a colonel (commanding), lieutenant colonel, and at least one major. With attrition from disease, battle

casualties, and transfers, by the mid-war, most regiments averaged 300-400 men. Volunteer regiments were paid by the individual

states, and officers at first were normally elected by popular vote, or were appointed by the state governors (particularly

the colonels, who were often the men who had raised and organized the regiment). As the war progressed, the War Department

and superior officers began selecting regimental leaders, and the regimental officers normally selected the NCOs (non-commissioned

officers) based on performance and merit, although the individual states retained considerable influence in the selection

of the regimental officers.

Often, not always, according to Hardee's 1855 manual, large regiments were

broken into two or more battalions, with the lieutenant colonel and major(s) in charge of each battalion. The regiment

may have also been divided into two wings, the left and right, for instructional purposes, only. The regimental commander

exercised overall tactical control over these officers and usually relied on couriers and staff to deliver and receive messages

and orders. Normally positioned in the center of the regiment in battle formation was the color guard, typically five to eight

men assigned to carry and protect the regimental and/or national colors, led by a color sergeant. Most Union regiments carried

both banners; the typical Confederate regiment simply had a national standard.

Individual regiments (usually three to five, although the number varied)

were organized and grouped into a larger body (a brigade) which soon became the main structure for battlefield maneuvers.

Generally, the brigade was commanded by a brigadier general or senior colonel, when merit was clearly evident in that colonel

and a Brigadier was not available. Two to four brigades typically comprised a division, which in theory was commanded by a

major general, but theory was often not put into practical application, especially when an officer exhibited exceptional merit

or the division was smaller and trusted to a more junior officer. Several divisions would constitute a corps, and multiple

corps together made up an army, often commanded by a lieutenant general or full general in the Confederate forces, and by

a major general in the Union forces.

| Civil War Infantry Chart |

|

| Civil War Infantry Chart indicates army organization and structure |

Trained in the era of short-range smoothbore muskets, such as

the Springfield Model 1842, which was issued to many units immediately prior to the war, many generals often did not fully

appreciate or understand the importance and power of the new weapons introduced during the war, such as the 1861 Springfield

musket and comparable rifles which had longer range and were more powerful than the weapons used by the antebellum armies.

Its barrel contained several rifled grooves that provided increased accuracy, and fired a .58 caliber Miniť ball (a small

conical-shaped ball). This rifle had a deadly effect up to 600 yards and was capable of seriously wounding a man beyond 1,000

yards, unlike the previous muskets used during the American Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars, most of which had an effective

range of only 100 yards.

Even smoothbore muskets underwent improvements: soldiers developed the technique

of "buck and ball," loading the muskets with a combination of small pellets and a single round ball, effectively making their

fire scattergun-like in effect. Other infantrymen went into combat armed with shotguns, pistols, knives, and assorted other

killing instruments. Very early in the war, a few companies were armed with pikes. However, by the end of 1862, most infantrymen

were armed with rifles, including imports from Great Britain, Belgium,

and other European countries.

The typical Union soldier carried his musket, percussion cap box, cartridge

box, a canteen, a knapsack, and other accouterments, in addition to any personal effects. By contrast, many Southern soldiers

carried their possessions in a blanket roll worn around the shoulder and tied at the waist. They might have a wooden canteen,

a linen or cotton haversack for food, and a knife or similar sidearm, as well as their musket. See also Civil War Weapons, Firearms, and Small Arms.

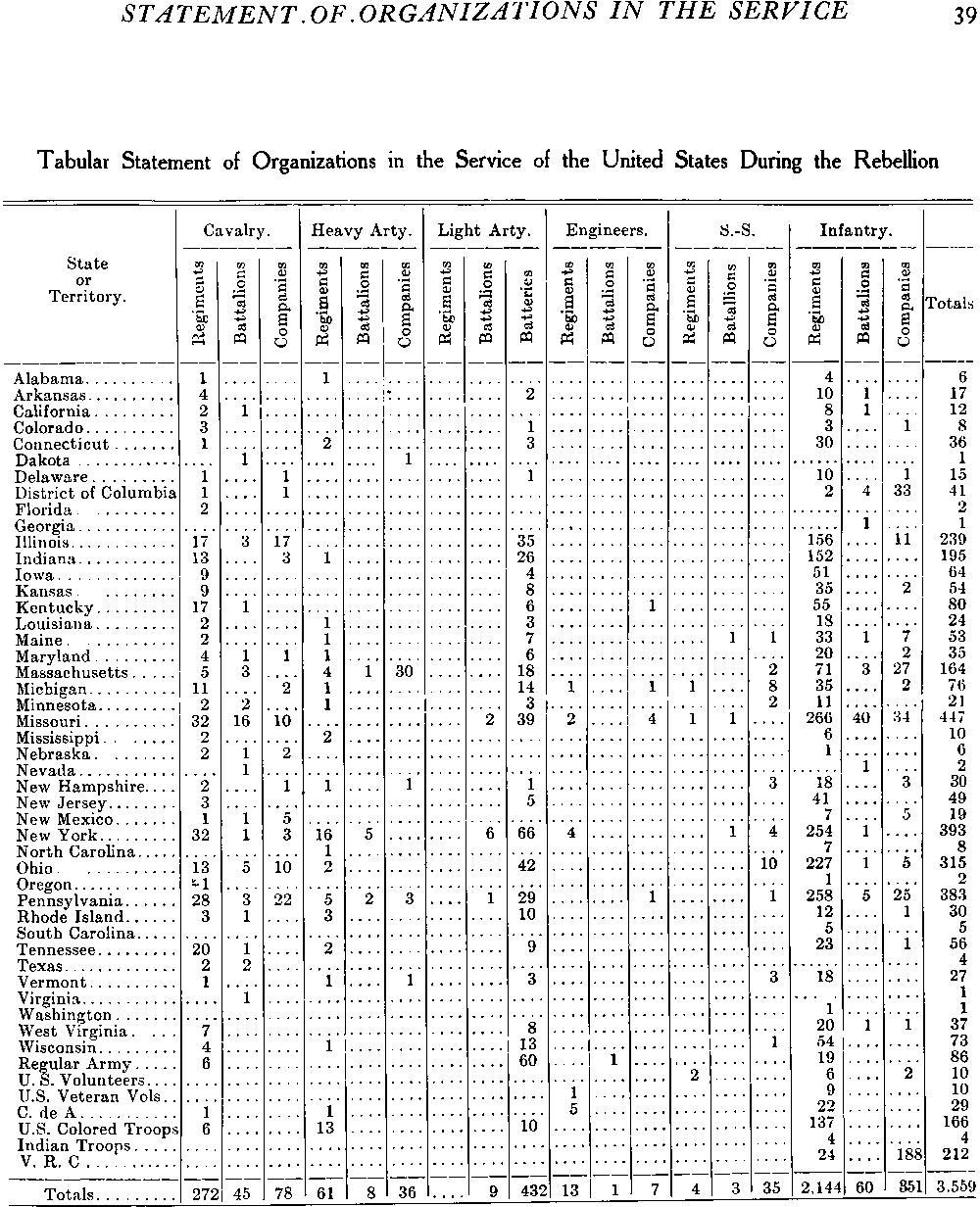

| Total Civil War Infantry Regiments |

|

| Total number of regiments from each state serving the Union military. Dyer |

(Above) Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (1908).

Dyer, in his table, indicates the total number of units--infantry, cavalry, artillery, engineers, and sharpshooters--for

each state, North and South, that supported the Union, and in the bottom right corner is the grand total. There were more

infantry regiments, however, in the Union military than all other regiments combined. The Union Army organization consisted

primarily of infantry, cavalry, and artillery. Dyer and Fox, acclaimed Civil War statisticians, spent decades compiling comprehensive

data for each unit and state, Union and Confederate, with exhaustive but readable works. Consequently, as foremost experts

in their respective fields, Dyer and Fox are quoted and referenced by most historians and authors.

Infantry Tactics

The tactical legacy of the eighteenth century had emphasized

close-order formations of soldiers trained to maneuver in concert and fire by volleys. These “linear” tactics

stressed the tactical offensive. Assault troops advanced in line, two ranks deep, with cadenced steps, stopping to fire volleys

on command and finally rushing the last few yards to pierce the enemy line with a bayonet charge.

These tactics were adequate for troops armed with single-shot,

muzzle-loading, smoothbore muskets with an effective range of about eighty yards. The close-order formation was therefore

necessary to concentrate the firepower of these inaccurate weapons. Bayonet charges might then succeed because infantry could

rush the last eighty yards before the defending infantrymen could reload their muskets after firing a volley.

The U.S. Army’s transition from smoothbore muskets to

rifles in the mid-nineteenth century would have two main effects in the American Civil War: it would strengthen the tactical

defensive and increase the number of casualties in the attacking force. With a weapon that could cause casualties out to 1,000

yards defenders firing rifles could decimate infantry formations attacking according to linear tactics.

| Civil War Infantry |

|

| Civil War Infantry in battle formation. Both Union and Confederate Infantry applied the same tactics |

|

|

|

|

|

A typical combat formation of a regiment might be six companies

in the main line, with two in reserve, and two out in front in extended skirmish order. Additional companies might be fed

into the skirmish line, or the skirmishers might regroup on the main line.

Later in the Civil War the widespread use of the rifle often

caused infantry assault formations to loosen up somewhat, with individual soldiers seeking available cover and concealment.

However, because officers needed to maintain visual and verbal control of their commands during the noise, smoke, and chaos

of combat, close-order tactics to some degree would continue to the end of the war.

Rapid movement of units on roads or cross-country was generally

by formation of a column four men abreast. The speed of such columns was prescribed as two miles per hour. Upon reaching the

field each regiment was typically formed into a line two ranks deep, the shoulders of each man in each rank touching the shoulders

of the man on either side. The distance between ranks was prescribed as thirteen inches. A regiment of 500 men (250 men in

each rank) might have a front of about 200 yards.

Both front and rear ranks were capable of firing, either by

volley or individual fire.

Volley Fire

Volley fire, as a military tactic, is the practice of having a line of soldiers

all fire their guns simultaneously at the enemy forces on command, usually to make up for inaccuracy, slow rate of fire, and

limited range, and to create a maximum effect. Although it was an ancient practice, Napoleon incorporated and perfected the

volley fire as witnessed by the numerous enemies that fell before the Frenchman's feet.

| Civil War Infantry and Military Tactics |

|

| Results of applying Napoleonic Tactics during the Civil War |

| Civil War Infantry applying Napoleonic Tactics |

|

| Civil War Infantry firing by rank and file |

The history of volley fire dates back before guns to use by archers, at

the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, for instance. One example of this is the Mongol Army. Another is the Persian invasion force

of King Xerxes, whose arrows were said to block the sun. In the eighteenth century, the British would use volley fire to make

up for the inaccuracy and limited range (100 yards) of their musket, the Brown Bess. Armies approached one another in linear

formations. British soldiers would fire volleys in the general direction of the enemy, by ranks. The command they were given

was to level weapons, rather than to aim. The shooters might be formed in three ranks, with the front rank firing simultaneously,

then the second rank, offset, then the third, after which the first rank was ready to fire again. Effective volley fire required

practice in swiftly completing the required motions. During the American Civil War volley fire was used quite effectively,

since the effective range and rate of fire were greater than in earlier centuries. Both the Union and Confederate armies had

superior weapons than their predecessors who had applied Napoleon's tactics, so the results of ancient, outdated tactics

used with modern rifled muskets in the hands of veteran Civil War soldiers meant mass casualties.

While weapons had advanced with recent technology, Union and Confederate

armies continued to apply outdated Napoleonic Tactic, resulting in unprecedented loss of life during the Civil War.

Napoleonic tactics describe

certain battlefield strategies used by national armies from the late 18th century until the invention and adoption of the

rifled musket in the mid 19th century. Napoleonic tactics are characterized by intense drilling of the soldiers, speedy

battlefield movement, combined arms assaults between infantry, cavalry, and artillery, relatively small numbers of cannon,

short-range musket fire, and bayonet charges. Napoleon I is considered by military historians to have been a master of this

particular form of warfare. Napoleonic tactics continued to be used after they had become technologically impractical, leading

to large-scale slaughters during the American Civil War.

Integration of Infantry at Battle

of Gettysburg

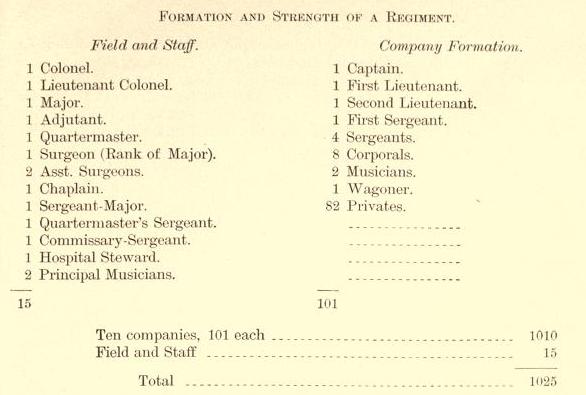

| Civil War Infantry Regiment Strength & Structure |

|

| Civil War Infantry Regiment Organization and Structure Table. Fox, William F. |

The armies that marched into Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863 were

well acquainted with each other. The Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Major General George G. Meade, had been at the

literal mercy of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee, for nearly nine months prior

to opening of the Gettysburg Campaign. Though Union forces often outnumbered Lee's forces on any given battlefield, Lee's

brilliant tactics, the leadership of his generals, and the spirit of his troops had secured numerous victories for the Confederacy,

among them the humiliating defeat of the Army of the Potomac at Fredericksburg in December 1862 and at the Battle of Chancellorsville

in May 1863. Morale among Lee's victorious soldiers was at an all time high and the invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania

that summer provided an added boost. Yet the Union Army was far from being a totally dejected lot. Though poor morale and

crushed spirits caused hundreds of men to desert the Army of the Potomac, the ranks were still filled with veteran soldiers

determined to see the war through. Though their army had suffered terrible losses, most reasoned that these defeats were caused

by the constant change in army command, poor generals, and interference from politicians, not by their will to fight. With

the Army of Northern Virginia now on Northern soil, the Union men found their roles to be one of liberation, unanimous in

their determination to drive Lee's Confederates out of the North. It was enough for many of the deserters to rejoin the ranks

as the army set out in pursuit of Lee.

The armies that fought the Battle of Gettysburg were similar in many

ways. They were organized in a similar fashion of "rank and file" with privates and sergeants, lieutenants and captains, majors

and colonels, quartermasters and clerks, teamsters and ordnance officers. Both armies drilled using similar instruction manuals,

marched to an almost identical drum beat, used similar weapons, and lived most of their soldier days in tented camps or sleeping

under the stars. The soldiers who wore the blue and the gray also shared many similarities. Most had been farmers before the

war, thrust into the conflict as volunteers in 1861 with the belief the war would last only a few short months. Others joined

later or were conscripted (drafted) into service, convinced that they were needed but uncertain of their place in protecting

their homes while being so far away from them. Still others were "substitutes" paid to join the army by others rich enough

to afford the $300 necessary to buy another man's services. Though politics and causes were different, Yank and Reb alike

served to protect their homes, their states, and the rights for which each soldier deeply believed just. Most of the soldiers

were young men, the average age approximately 21 years. By the summer of 1863, these young men were hardened veterans of war,

experienced to the rigors of marching long distances and the horror of battle. For most, war-time service was a brutal journey

into manhood.

A variety of weapons was carried at Gettysburg. Revolvers, swords,

and bayonets were abundant, but the basic infantry weapon of both armies was a muzzle-loading rifle musket about 4.7 feet

long, weighing approximately 9 pounds. They came in many models, but the most common and popular were the Springfield and

the English-made Enfield. They were hard hitting, deadly weapons, very accurate at a range of 200 yards and effective at 1,000

yards. With black powder, ignited by percussion caps, they fired "Minie Balls"—hollow-based lead slugs half an inch

in diameter and an inch long. A good soldier could load and fire his rifle three times a minute, but in the confusion of battle

the rate of fire was probably slower.

There were also some breech-loading small arms at Gettysburg. Union

cavalrymen carried Sharps and Burnside single-shot carbines and a few infantry units carried Sharps rifles. Spencer repeating

rifles were used in limited quantity by Union cavalry on July 3 and by a few Union infantry. In the total picture of the battle,

the use of these efficient weapons was actually quite small.

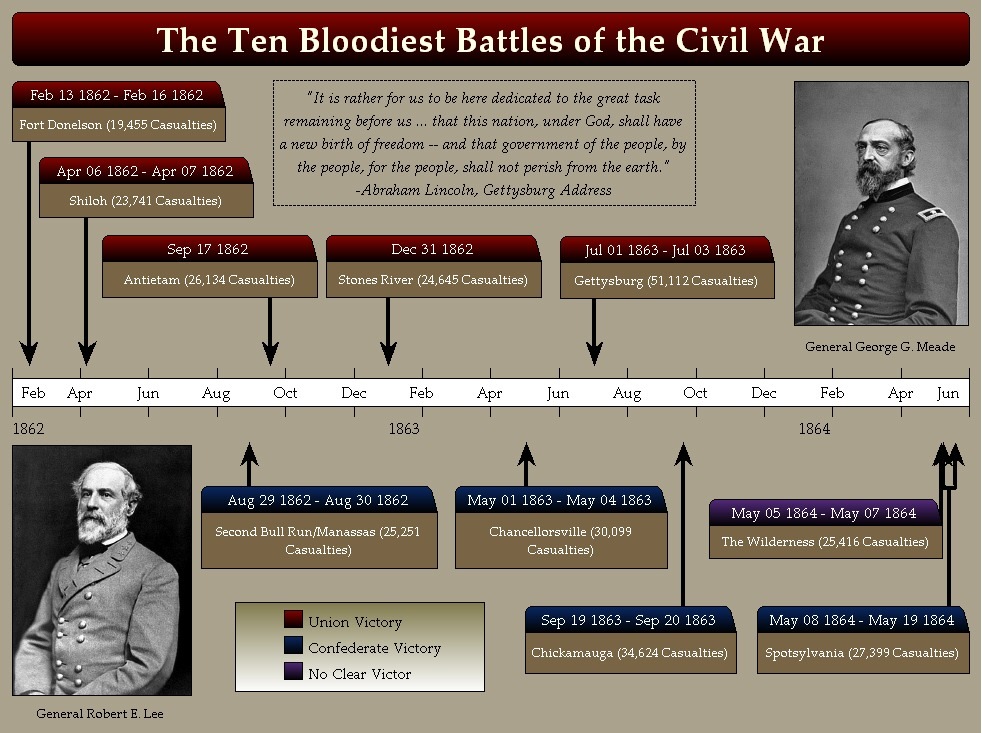

| Civil War Infantry and Casualties |

|

| The Civil War infantry unit was responsible for more battlefield deaths than any other military unit |

Those who fought at Gettysburg with rifles and carbines were supported

by nearly 630 cannon—360 Union and 270 Confederate. About half of these were rifled iron pieces, all but four of the

others were smoothbore bronze guns. The same types of cannon were used by both armies.

Almost all of the bronze pieces were 12 pounders, either howitzers

or "Napoleons." They could hurl a 12-pound iron ball nearly a mile and were deadly at short ranges, particularly when firing

canister. Other bronze cannon included 24 pounder howitzers and 6 pounder guns. All types are represented in the park today,

coated with patina instead of being polished as they were when in use.

Most of the iron rifled pieces at Gettysburg had a 3-inch bore and

fired a projectile which weighed about 10 pounds. There were two types of these—3-inch ordnance rifles and 10 pounder

Parrotts. It is easy to tell them apart for the Parrott has a reinforcing jacket around its breech, The effective range of

these guns was somewhat in excess of a mile, limited in part because direct fire was used and the visibility of gunners was

restricted.

Two other types of rifled guns were used at Gettysburg—four bronze

James guns and two Whitworth rifles. The Whitworths were unique because they were breech loading and were reported to have

had exceptional range and accuracy. However, their effect at Gettysburg must have been small for one was out of action much

of the time.

These artillery pieces used three types of ammunition. All cannon could

fire solid projectiles or shot. They also hurled fused, hollow shells which contained black powder and sometimes

held lead balls or shrapnel. Canister consisted of cans filled with iron or lead balls. These cans burst apart on firing,

converting the cannon into an oversized shotgun.

Weapons influenced tactics. At Gettysburg a regiment formed for battle,

fought, and moved in a two rank line, its men shoulder to shoulder, the file closets in the rear. Since the average strength

of regiments here was only 350 officers and men, the length of a regiment's line was a little over 100 yards. Such a formation

brought the regiment's slow-firing rifles together under the control of the regimental commander, enabling him to deliver

a maximum of fire power at a given target. The formation's shallowness had a two-fold purpose, it permitted all ranks to fire,

and it presented a target of minimum depth to the enemy's fire.

Four or five regiments were grouped into a brigade, two to five brigades

formed a division. When formed for the attack, a brigade moved forward in a single or double line of regiments until it came

within effective range of the enemy line. Then both parties blazed away, attempting to gain the enemy's flank if feasible,

until one side or the other was forced to retire. Confederate attacking forces were generally formed with an attacking line

in front and a supporting line behind. Federal brigades in the defense also were formed with supporting troops in a rear line

when possible. Breastworks were erected if time permitted, but troops were handicapped in this work because entrenching tools

were in short supply.

Like their infantry comrades, cavalrymen also fought on foot, using

their horses as means of transportation. However, mounted charges were also made in the classic fashion, particularly in the

great cavalry battle on July 3.

Cavalry and infantry were closely supported by artillery. Batteries

of from four to six guns occupied the crests of ridges and hills from which a field of fire could be obtained. They were usually

placed in the forward lines, protected by supporting infantry regiments posted on their flanks or in their rear. Limbers containing

their ammunition were nearby. Because gunners had to see their targets, artillery positions sheltered from the enemy's view

were still in the future.

| Civil War infantry |

|

| While the objective of the infantryman was to fight a battle and win, 620,000 died in the process |

Analysis

The

Civil War caused 620,000 killed, and it forced the United States military to reexamine its stiff, outdated tactics and

strategies that had led to the carnage. The U.S. Military Academy, U.S. Naval Academy, and other military schools would

adapt, improvise, and overcome to meet the present and future challenges of war. After all, numerous inventions and innovations

were a result of the Civil War. The arts of tactics and strategy were revolutionized by the many developments introduced

during the 1860s. Thus the Civil War ushered in a new era in warfare with the: FIRST practical machine gun, FIRST repeating

rifle used in combat, FIRST use of the railroads as a major means of transporting troops and supplies, FIRST mobile siege

artillery mounted on rail cars, FIRST extensive use of trenches and field fortifications, FIRST large-scale use of land mines,

known as "subterranean shells", FIRST naval mines or "torpedoes", FIRST ironclad ships engaged in combat, FIRST multi-manned

submarine, FIRST organized and systematic care of the wounded on the battlefield, FIRST widespread use of rails for hospital

trains, FIRST organized military signal service, FIRST visual signaling by flag and torch during combat, FIRST use of portable

telegraph units on the battlefield; FIRST military reconnaissance from a manned

balloon, FIRST draft in the United States, FIRST organized use of Negro troops in combat, FIRST voting in the field for a

national election by servicemen, FIRST income tax—levied to finance the war, FIRST photograph taken in combat, FIRST

Medal of Honor awarded an American soldier. See also Civil War Comparison of the North

and South.

Sources: The Ohio State University Department of History (used by permission);

United States Army Staff Rides Series; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Library of Congress, National

Archives; National Park Service; The Union Army (1908); Fox, William F. Regimental Losses in the American Civil War (1889);

Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (1908); Boatner, Mark M., The Civil War Dictionary: Revised Edition.

New York: Vintage Books, 1991. ISBN 0-679-73392-2; Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford

University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3; Faust, Patricia L., ed., The Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War. Harper

Collins, 1986. ISBN 0-06-181261-7; Griffith, Paddy. Battle Tactics of the Civil War (1989); Hagerman, Edward. The American

Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare: Ideas, Organization, and Field Command (1992); Hardee, William J. Rifle and Light

Infantry Tactics: For the Exercise and Manoeuvres of Troops when Acting as Light Infantry or Riflemen (United States War Department,

1855); Gettysburg National Military Park.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|