|

|

US Civil War Tactics and Strategy Plan

Union and Confederate Military History

Introduction

It can be accurately stated that although the Union strategy was successful, its

tactics were not.

Can a single component, one branch of the armed forces, of a nation's military subdue its

foe? Is an army or navy alone capable of defeating an enemy? Those questions have been asked and debated since antiquity

itself, but whether or not a navy or army alone is capable of defeating an enemy is not an answer which can be stated

factually for every nation and its armed forces. The United States has asked the question and often answered it by trial and

error during times of war, because the answer rests not only in the superiority of a nation's navy or army and its risk to

casualties, but equally in the enemy's ability to withstand the assaults and its will and capability to continue waging

war.

A nation which engages in war does so with the understanding that loss of life is inevitable.

When there is war, there is risk, including casualties, so when a nation involves one branch of its armed forces it does so

with the desire to minimize its exposure to risk and to reduce its wartime casualties. Any nation which utilizes one

branch of its military while reducing risk with the perception that victory over an enemy is achievable, it does

so with the implied acknowledgement that it is not willing to sustain high losses to achieve it primary objective

of victory during the confrontation. The element which then becomes a determining factor deciding if another

branch, the navy for example, is introduced into the fight, becomes a matter of popular opinion. Will the public support

its leader's decision to deploy and utilize more of its military power and broaden or escalate the conflict?

The decision historically has almost overwhelmingly been no.

| Civil War Tactics. |

|

| The Strategy of the Civil War involved obsolete tactics. |

| Civil War tactics with line of battle formation. |

|

| Union military tactics by rank and file. Ca. 1863. LOC. |

(About) The Union and Confederate armies continued to implement obsolete tactics with the arrival

of the new conical shaped Minie ball and highly effective rifle-musket, causing mass casualties to be the norm and not the

exception on the nation's battlefields. The rifle-musket would be responsible for approximately 90% of the total battlefield

deaths.

Prior to the American Civil War, some of the nation's leaders strived to reduce risk by initially

planning to introduce limited ground forces and a large scale naval blockade to force the Southern states into submission

by denying them the ability to both ship and receive goods. The Northern politicians and their constituents bulked at a strategy

of trying to squeeze the South into defeat, but demanded that the entire weight and might of the armed forces of the United

States be brought to bear on the rebellion south of the Mason and Dixon.

With the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter, in South Carolina, the drums of war only grew

louder until the nation was finally committed and engaged in full-scale Civil War. Some had thought that the war

would now be over in just 90 days, a notion that was later bemoaned as the nation's casualties began to rise to

levels unimaginable prior to the conflict.

President Abraham Lincoln, however, pursued a strategy that involved both the naval blockade

and full complement of the Union military, but tactics were outdated the moment they were introduced, because smoothbore muskets, with their effective range of 75 yards, and Napoleonic Tactics, which had once gained famed, had now been supplanted with the recent invention of the Minie ball and musket-rifle,

a lethal combination that would allow the conical shaped projectile to traverse the battlefield at a distance of more

than 500 yards. Whereas the day of rank and file soldiers in massed line of battle formations at

merely 100 yards to deliver their inaccurate musket balls in hopes of increasing the odds of hitting the troops continued,

the combination was rendered obsolete as infantrymen gripped the more powerful Enfield

and Springfield rifle-muskets with their respective ranges of some 500 yards. With the exception of Lee and Grant stalled in the trenches

of Richmond-Petersburg for more than nine months, the old Napoleon Tactics would remain until the war had claimed

some 620,000 lives.

Although public sentiment wavered at times during the four year war, the commander-in-chief maintained

his commitment of seeing the war to its end, regardless. The President committed all of the resources of the nation

to a war that seemed to have no end, but with a clarion sound of "all for the Union" from the Whitehouse, the citizens of

the Northern states also pushed onward with a desire to finish what it had initially demanded- the restoration of the Union.

The Union Civil War Strategy and Tactics

The initial military strategy offered to President Abraham Lincoln for crushing the rebellion in the Southern states was devised by Union General-in-Chief

Winfield Scott and it did not involve the army. From April 1 through early May 1861, Scott briefed the president daily, often

in person, on the national military situation; the results of these briefings were applied by Scott to fulfill Union

military aims. Scott mulled over involving both infantry and navy to achieve a quick, decisive Union victory, but

ultimately he believed that the navy, with minimal loss of life, could accomplish the goal.

| Civil War Strategy and Tactics |

|

| When Total War Arrived at Columbia, South Carolina, the Capital was Reduced to Rubble. |

In early May, Scott informed

his protégé, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, that he believed an effective "Blockade" of Southern ports, a strong thrust down

the Mississippi Valley with a large force, and the establishment of a line of strong Federal positions there would isolate

the disorganized Confederate nation "and bring it to terms." Contemporary sources indicate that McClellan referred

to it as Scott's "boa-constrictor" plan. Scott then presented it to the president, in greater detail, proposing

that 60,000 troops traverse the Mississippi with gunboats until they had secured the river from Cairo, Ill., to the Gulf,

which, in concert with an effective blockade, would seal off the South. Then, he believed, Federal troops should stop, waiting

for Southern Union sympathizers to turn on their Confederate governors and compel them to surrender. It was his belief that

sympathy for secession was not as strong as it appeared and that isolation and pressure would make the "fire-eaters" back

down and allow calmer heads to take control.

But the war-fevered nation wanted combat, not armed diplomacy, and the

passive features of Scott's plan were ridiculed as a proposal "to squeeze the South to military death." The press, recalling

McClellan's alleged "boa-constrictor" remark, named the plan after a different constricting snake, the anaconda. Although

the Anaconda Plan was not fully implemented, in 1864 it reappeared in aggressive form. Lt.

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's 2-front war, fought in Virginia and Tennessee, pressed the Confederates, while Maj. Gen. William T.

Sherman's march through Georgia to the sea helped "squeeze the South to military death." Ultimately, it was the grunt, the

infantry, causing massive casualties unthinkable to the nation, that was involved in the majority of the fighting

during the four year costly war.

In this military art, troops are maneuvered outside the battlefield to achieve

success in a large geographic area. That geographic expanse can be a "front" (in the Civil War, part or all of one state)

or a "theater" (several contiguous states possessing geographical, geopolitical, or military unity). When the expanse encompasses

an entire country, the corresponding waging of war on the largest scale to secure national objectives is called "grand strategy."

"Offensive strategy" carries war to the enemy, either directly by challenging

his strength or indirectly by penetrating his weakness. "Defensive strategy" protects against enemy strategic offensives. And "defensive-offensive strategy" (which Confederates often practiced) uses offensive maneuvers for defensive

strategic results (e.g., Gen. R. E. Lee and Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson took the offensive May-June 1862 to defend

Richmond and Virginia).

Strategic objectives include defeating, destroying, or forcing enemy

armies to retreat; seizing enemy strategic sites (supply lines, depots, arsenals, communications centers, and industry) crucial

to his military effort; capturing the enemy capital; disrupting his economy; and demoralizing his will to wage war. While

seeking such goals, the strategist must correspondingly protect his own army, strategic sites, capital, economy, and populace.

He must strike proper balance between securing his rear and campaigning in his front. Supply lines and homelands must be guarded;

especially in war between 2 republics, which the Civil War really was, the compelling necessity of protecting the political

base cannot be ignored. Yet if too many troops are left in the rear, too few remain to attack or even defend against enemy

armies at the front.

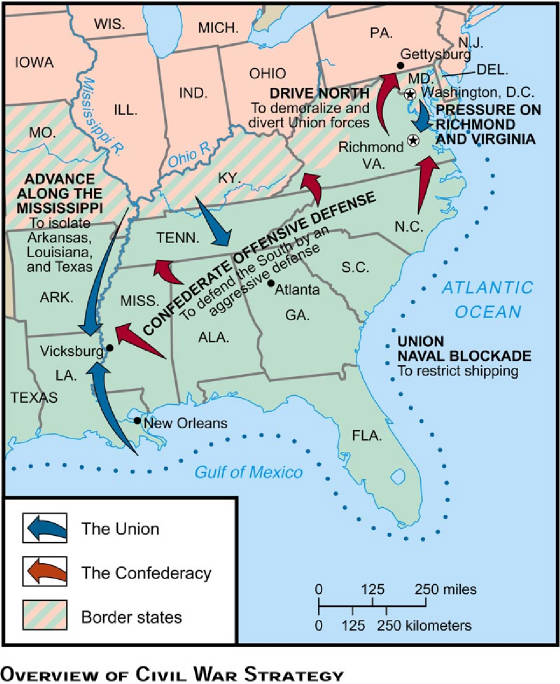

| Civil War Military Strategy and Tactics |

|

| (Map) Scott's Civil War Anaconda Plan |

Of these objectives, European experience, from which Civil War strategic

doctrine derived, emphasized 3 strategies: destroying the enemy's army in 1 battle, seizing strategic sites, and capturing

the enemy's capital. In the Civil War, attacking and defending Richmond and Washington consumed much effort, but their actual

strategic importance, though great, was more symbolic than substantial, since neither was its country's nerve center, as European

capitals were. Also illusory were quests for victory through seizing strategic sites and cutting "lines of communication"

(supply lines); only a few Civil War campaigns, such as Holly Springs and Second Bull Run, were decided or even significantly

affected by such captures. Most chimerical of all were hopes of annihilating the enemy's army in 1 great Napoleonic victory.

Rather, Civil War strategists used a series of battles--each of them indecisive but cumulatively effective--to cripple

the enemy, drive him back, and overrun or protect territory. Some strategies aimed directly at such battles. Other strategies

sought first to maneuver so as to gain advantage of ground or numbers and only then to give battle under such favorable conditions.

Whatever the overall numbers in the theater, strategy strove to assure numerical superiority on the battlefield; this principle

was called "concentrating masses against fractions." Both sides practiced it, but it was especially important to the overall

weaker Secessionists, as when Jackson performed it so effectively in the Shenandoah Valley.

Again, each side, particularly the Confederates, used "interior lines" to move forces from quiet fronts through the

interior to threatened fronts more quickly than the enemy could move around the military border. But, in practice, Southern

supply lines were so primitive and Federal supply lines were so good that, despite longer distance, Northerners often moved

in shorter time due to their "superior lateral communications." Even more effective against Confederate reliance on interior

lines was Ulysses S. Grants grand strategy of concerting the armed might of the Union for simultaneous advances to pin and

defeat Confederate troops on all major fronts.

Besides these approaches, Civil War strategists, especially Union commanders such as William T. Sherman and Philip

H. Sheridan, usually reluctantly but increasingly came to make the enemies economy and populace suffer. For the first time

since the Thirty Years War, those 2 targets regained legitimacy. While free from the brutality of 1618-48, Federal strategy

eventually crippled Southern capability and will to wage war though, to be effective, such strategy could only complement

Northern success in maneuver and battle.

Long-range strategic cavalry raids -- in brigade to corps strength -- played some role in such crippling, but those

raids rarely had much military effect before collapse became imminent in 1865. Instead, the principal unit of strategic maneuver

was the infantry corps, and the basic element of strategic control was the army. And in theaters where I side had several

armies, those armies themselves became maneuver units, and control resided at military division headquarters or with the general-in-chief

himself. Whatever the elements and whatever the means, the fundamental goal of strategy remains the same: the overall use

of force to accomplish broad military and political objectives.

| Civil War Union Strategy Map |

|

| Union Strategy Map for Victory over Confederacy |

Tactics is the military art of maneuvering troops on the field of battle

to achieve victory in combat. 'Offensive tactics" seek success through attacking; "defensive tactics" aim at defeating enemy attacks.

In Civil War tactics, the principal combat arm was infantry. Its most

common deployment was a long "line of battle," 2 ranks deep. More massed was the "column," varying from 1 to 10 or more companies

wide and from 8 to 20 or more ranks deep. Less compact than column or line was "open-order" deployment: a strung-out, irregular

single line.

Battle lines delivered the most firepower defensively and offensively.

Offensive firepower alone would not ensure success. Attackers had to charge, and massed columns, with their greater depth,

were often preferable to battle lines for making frontal assaults. Better yet were flank attacks, to "roll up" thin battle

lines lengthwise. Offensive tacticians sought opportunity for such effective flank attacks; defensive tacticians countered

by "refusing" these flanks on impassable barriers. In either posture, tacticians attempted to coordinate all their troops

to deliver maximum force and firepower and to avoid being beaten "in detail" (piecemeal). Throughout, they relied on open-order

deployment to cover their front and flanks with skirmishers, who developed the enemy position and screened their own troops.

Open order, moreover, was best suited for moving through the wooded

countryside of America. That wooded terrain, so different from Europe's open fields, for which tactical doctrine was aimed,

also affected tactical control. Army commanders, even corps commanders, could not control large, far-flung forces. Instead,

army commanders concentrated on strategy. And corps commanders handled "grand tactics": the medium for translating theater

strategy into battlefield tactics, the art of maneuvering large forces just outside the battlefield and bringing them onto

that field. Once on the field, corps commanders provided overall tactical direction, but their largest practical units of

tactical maneuver were divisions. More often, brigades, even regiments, formed those maneuver elements. Essentially, brigades

did the fighting in the Civil War.

Besides affecting organization, difficult terrain helped relegate cavalry

and artillery to lesser tactical roles. More influential there was the widespread use of long-range rifled shoulder arms.

As recently as the Mexican War, when most infantry fired smoothbore muskets, cavalry and artillery had been key attacking

arms. Attempting to continue such tactics in the Civil War proved disastrous, as infantry rifle power soon drove horsemen

virtually off the battlefield and relegated artillery to defensive support. Rifle power devastated offensive infantry assaults,

too, but senior commanders, who were so quick to understand its. impact on cannon and cavalry, rarely grasped its effect on

infantry. By 1864, infantry customarily did erect light field fortifications to strengthen its defensive battlefield positions

and protect itself from enemy rifle power; but when attacking, whether against battle lines or fortifications, infantry continued

suffering heavy casualties through clinging to tactical formations outmoded by technology.

|

|

|

|

|

(About) Civil Ware tactics resulted in massed formations and frontal assaults.

Courtesy National Guard, by Don Troiani, HistoricalArtPrints.com

But if infantry was slow to learn, other arms swiftly found new tactical

roles. The new mission of the artillery was to bolster the defensive, sometimes with 1 battery assigned to each infantry brigade,

but more often with I battalion assigned to a Confederate infantry division and 1 brigade to a Federal infantry corps. With

long-range shells and close-in canister, artillery became crucial in repulsing enemy attacks. But long-range shelling to support

ones own attack had minimal effect, and artillery assaults were soon abandoned as suicidal. Throughout, artillery depended

almost entirely on direct fire against visible targets.

Cavalry, in the meantime, served most usefully in scouting for tactical

intelligence and in screening such intelligence from the foe. By midwar, moreover, cavalry was using its mobility to seize

key spots, where it dismounted and fought afoot. Armed with breech-loading carbines, including Federal repeaters by 1864-65,

these foot cavalry fought well even against infantry. Only rarely did mounted cavalry battle with saber and pistol. Rarer

still were mounted pursuits of routed enemies.

Cavalry so infrequently undertook such pursuits chiefly because

defeated armies were rarely routed. Size of armies, commitment to their respective causes by individual citizen-soldiers,

difficult terrain, and impact of fortifications and technology all militated against the Napoleonic triumph, which could destroy

an enemy army--and an enemy country--in just 1 battle. Raised in the aura of Napoleon,

most Civil War commanders sought the Napoleonic victory, but few came close to achieving it. 60 years after Marengo

and Austerlitz, warfare had so changed that victory in the Civil War would instead come through strategy. Yet within that

domain of strategy, not just 1 battle but series of them--and the tactics through which they were fought--were the crucial

elements in deciding the outcome of the Civil War. See also Army Warfare and Napoleonic Tactics.

Armies,

Weapons, and Tactics at Gettysburg

| Civil War Tactics of army, navy, and ground forces |

|

| Civil War Tactics evolved from a blockade to boots on the ground. |

The

armies that marched into Pennsylvania in the summer of 1863 were well acquainted with each other. The Union Army of the Potomac,

commanded by Major General George G. Meade, had been at the literal mercy of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, commanded

by General Robert E. Lee, for nearly nine months prior to opening of the Gettysburg Campaign. Though Union forces often outnumbered

Lee's forces on any given battlefield, Lee's brilliant tactics, the leadership of his generals, and the spirit of his troops

had secured numerous victories for the Confederacy, among them the humiliating defeat of the Army of the Potomac at Fredericksburg

in December 1862 and at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. Morale

among Lee's victorious soldiers was at an all time high and the invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania that summer provided

an added boost. Yet the Union Army was far from being a totally dejected lot. Though poor morale and crushed spirits caused

hundreds of men to desert the Army of the Potomac, the ranks were still filled with veteran soldiers determined to see the

war through. Though their army had suffered terrible losses, most reasoned that these defeats were caused by the constant

change in army command, poor generals, and interference from politicians, not by their will to fight. With the Army of Northern

Virginia now on Northern soil, the Union men found their roles to be one of liberation, unanimous in their determination to

drive Lee's Confederates out of the North. It was enough for many of the deserters to rejoin the ranks as the army set out

in pursuit of Lee.

The armies that fought the Battle of Gettysburg were similar in many

ways. They were organized in a similar fashion of "rank and file" with privates and sergeants, lieutenants and captains, majors

and colonels, quartermasters and clerks, teamsters and ordnance officers.

Both armies drilled using similar instruction manuals, marched to an almost identical drum beat, used similar weapons, and

lived most of their soldier days in tented camps or sleeping under the stars. The soldiers who wore the blue and the gray

also shared many similarities. Most had been farmers before the war, thrust

into the conflict as volunteers in 1861 with the belief the war would last only a few short months. Others joined later or

were conscripted (drafted) into service, convinced that they were needed but uncertain of their place in protecting their

homes while being so far away from them. Still others were "substitutes" paid to join the army by others rich enough to afford

the $300 necessary to buy another man's services. Though politics and causes were different, Yank and Reb alike served to

protect their homes, their states, and the rights for which each soldier deeply believed just. Most of the soldiers were young

men, the average age approximately 21 years. By the summer of 1863, these young men were hardened veterans of war, experienced

to the rigors of marching long distances and the horror of battle. For most, war-time service was a brutal journey into manhood.

A variety of weapons was carried at Gettysburg. Revolvers, swords, and bayonets were abundant, but the basic

infantry weapon of both armies was a muzzle-loading rifle musket about 4.7 feet long, weighing approximately 9 pounds. They

came in many models, but the most common and popular were the Springfield and the English-made Enfield. They were hard hitting,

deadly weapons, very accurate at a range of 200 yards and effective at 1,000 yards. With black powder, ignited by percussion

caps, they fired "Minie Balls"—hollow-based lead slugs half an inch in diameter and an inch long. A good soldier could

load and fire his rifle three times a minute, but in the confusion of battle the rate of fire was probably slower.

There were also some breech-loading small arms at Gettysburg. Union cavalrymen carried Sharps and Burnside

single-shot carbines and a few infantry units carried Sharps rifles. Spencer repeating rifles were used in limited quantity

by Union cavalry on July 3 and by a few Union infantry. In the total picture of the battle, the use of these efficient weapons

was actually quite small.

| US CIvil War Tactics and Strategy Map |

|

| US Civil War Strategy and Tactics Plan Map |

Those who fought at Gettysburg with rifles and carbines were supported by

nearly 630 cannon—360 Union and 270 Confederate. About half of these were rifled iron pieces, all but four of the others

were smoothbore bronze guns. The same types of cannon were used by both armies.

Almost all of the bronze pieces were 12 pounders, either howitzers or "Napoleons." They could hurl a 12-pound

iron ball nearly a mile and were deadly at short ranges, particularly when firing canister. Other bronze cannon included 24

pounder howitzers and 6 pounder guns. All types are represented in the park today, coated with patina instead of being polished

as they were when in use.

Most of the iron rifled pieces at Gettysburg had a 3-inch bore and fired

a projectile which weighed about 10 pounds. There were two types of these—3-inch ordnance rifles and 10 pounder Parrotts.

It is easy to tell them apart for the Parrott has a reinforcing jacket around its breech, The effective range of these guns

was somewhat in excess of a mile, limited in part because direct fire was used and the visibility of gunners was restricted.

Two other types of rifled guns were used at Gettysburg—four bronze James guns and two Whitworth rifles.

The Whitworths were unique because they were breech loading and were reported to have had exceptional range and accuracy.

However, their effect at Gettysburg must have been small for one was out of action much of the time.

These artillery pieces used three types of ammunition. All cannon could fire solid projectiles or shot.

They also hurled fused, hollow shells which contained black powder and sometimes held lead balls or shrapnel. Canister

consisted of cans filled with iron or lead balls. These cans burst apart on firing, converting the cannon into an oversized

shotgun.

Weapons influenced tactics. At Gettysburg a regiment formed for battle, fought, and moved in a two rank line,

its men shoulder to shoulder, the file closets in the rear. Since the average strength of regiments here was only 350 officers

and men, the length of a regiment's line was a little over 100 yards. Such a formation brought the regiment's slow-firing

rifles together under the control of the regimental commander, enabling him to deliver a maximum of fire power at a given

target. The formation's shallowness had a two-fold purpose, it permitted all ranks to fire, and it presented a target of minimum

depth to the enemy's fire.

Four or five regiments were grouped into a brigade, two to five brigades formed a division. When formed for

the attack, a brigade moved forward in a single or double line of regiments until it came within effective range of the enemy

line. Then both parties blazed away, attempting to gain the enemy's flank if feasible, until one side or the other was forced

to retire. Confederate attacking forces were generally formed with an attacking line in front and a supporting line behind.

Federal brigades in the defense also were formed with supporting troops in a rear line when possible. Breastworks were erected

if time permitted, but troops were handicapped in this work because entrenching tools were in short supply.

Like their infantry comrades, cavalrymen also fought on foot, using their horses as means of transportation.

However, mounted charges were also made in the classic fashion, particularly in the great cavalry battle on July 3.

Cavalry and infantry were closely supported by artillery. Batteries of from four to six guns occupied the

crests of ridges and hills from which a field of fire could be obtained. They were usually placed in the forward lines, protected

by supporting infantry regiments posted on their flanks or in their rear. Limbers containing their ammunition were nearby.

Because gunners had to see their targets, artillery positions sheltered from the enemy's view were still in the future.

Strategy, Tactics, and Future Wars

The

Civil War caused 620,000 killed, and it forced the United States military to reexamine its stiff, outdated tactics and

strategies that had led to the carnage. The U.S. Military Academy, U.S. Naval Academy, and other military schools would

adapt, improvise, and overcome to meet the present and future challenges of war. After all, numerous inventions and innovations

were a result of the Civil War. The arts of tactics and strategy were revolutionized by the many developments introduced

during the 1860s. Thus the Civil War ushered in a new era in warfare with the: FIRST practical machine gun, FIRST repeating

rifle used in combat, FIRST use of the railroads as a major means of transporting troops and supplies, FIRST mobile siege

artillery mounted on rail cars, FIRST extensive use of trenches and field fortifications, FIRST large-scale use of land mines,

known as "subterranean shells", FIRST naval mines or "torpedoes", FIRST ironclad ships engaged in combat, FIRST multi-manned

submarine, FIRST organized and systematic care of the wounded on the battlefield, FIRST widespread use of rails for hospital

trains, FIRST organized military signal service, FIRST visual signaling by flag and torch during combat, FIRST use of portable

telegraph units on the battlefield; FIRST military reconnaissance from a manned

balloon, FIRST draft in the United States, FIRST organized use of Negro troops in combat, FIRST voting in the field for a

national election by servicemen, FIRST income tax—levied to finance the war, FIRST photograph taken in combat, FIRST

Medal of Honor awarded an American soldier. See also Civil War Comparison of the North

and South.

Sources: Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War; history.army.mil;

artwork courtesy Don Troiani; Library of Congress; US Army Center of Military History; Dyer, Frederick H., A Compendium of

the War of Rebellion (1908): Fox, William F. Regimental Losses in the American

Civil War (1889); Phisterer, Frederick. Statistical record of the armies of the United States (1883); Hardesty, Jesse. Killed and died of wounds in the Union army during the Civil War (1915) Wright-Eley

Co; Gettysburg National Military Park; National Archives; National Park Service.

Return to American Civil War Homepage

|

|

|