|

Battle of Plymouth, North Carolina

Civil War on the North Carolina Coast

Battle of Plymouth

Plymouth Civil War History

| Civil War Battle of Plymouth |

|

| (Plymouth, North Carolina) |

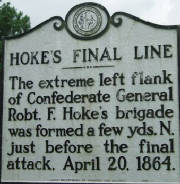

Confederates under Gen. Robert F. Hoke, aided by the ram "Albemarle,"

took the town, April 17-20, 1864.

History: In the midst of the Civil War, the Confederate

army succeeded capturing the county seat of Washington County in April of 1864. Referred to as “one of the most effective

Confederate combined-arms operation of the Civil War,” the Battle of Plymouth was the result of both Brig. Gen. Robert

F. Hoke’s infantry division and the naval support of the Confederate ironclads, the Albermarle and the Neuse.

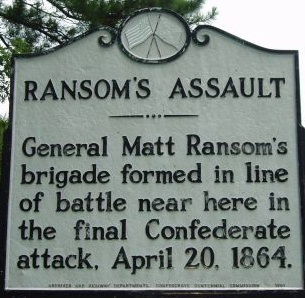

(Right) One of many Civil War historical markers celebrating the Confederate

victory at Plymouth, North Carolina.

The Union army had set up their eastern headquarters of North Carolina in

Plymouth and the town of New Bern in 1862, and the North led several offenses from their bases in these towns. Plymouth was

strategically located close to the Roanoke River, making naval warfare a necessity to capture the town. In hopes to regain

a stronghold in Carolina’s waterways, the Confederacy conspired to build two ships, the Albermarle and Neuse, in 1862.

Once the two naval vessels were completed, General Hoke developed a plan to attack Union forts off the coast of North Carolina.

Plymouth was the first town Hoke decided to invade.

On April 17, 1864, Hoke, along with 10,000 infantrymen, started the

advance on Plymouth. Brig. Gen. Henry W. Wessell commanded a Union force of some 3,000 men at the garrison in Plymouth, but,

having created a ring of forts, redoubts, and works in and around the city, the Federals handsomely repelled

many attempts of the advancing Confederate infantrymen. Early the next day, Hoke increased artillery fire on the Union Fort

Gray and Battery Worth, and the Union ship, the Bombshell, soon gave way to the heavy Confederate bombings.

Although Hoke continued his pressure on the Union defenses, his infantry

needed assistance in taking Fort Gray. The Albermarle, captained by James Cooke, answered the call of duty. Unusually

high river levels on the Roanoke allowed the Albermarle to scamper past Fort Gray without alerting the Union forces during

the early hours of April 19th. However, the USS Southfield and Miami, met Cooke’s vessel and a naval battle ensued.

Although the Miami was considered the most powerful ship on the river, the Albermarle managed to sink the Southfield as the

Miami retreated from the engagement.

| Civil War Battle of Plymouth |

|

| North Carolina Coast and the Civil War |

| Civil War Redoubt |

|

| (Historical Marker) |

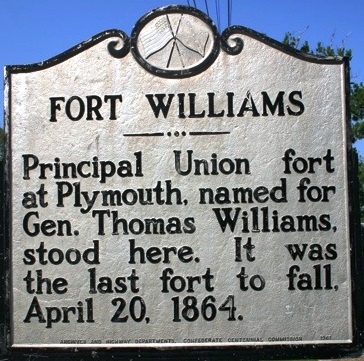

| Fort Williams |

|

| (Historical Marker) |

General Hoke finally had naval artillery support, and Confederate troops attacked Plymouth from the east

and west on April 20th. General Wessell refused to accept his predicament as General Hoke surrounded Fort Williams, the last

defense in Plymouth. The Federals remained in Fort Williams even though both Hoke’s artillery and the Albemarle

bombarded their defense throughout the entire morning. Finally, having been fully enveloped, General Wessell was compelled

to surrendered, and Hoke’s splendid victory renewed Confederate war vigor in North Carolina.

The victory at Plymouth opened Washington County back to the Confederacy, and much-needed naval stores were

made available to the army once again. In addition, the Roanoke River was freed from Union blockades, allowing for a trade

and military transportation route for Confederate forces.

Timeline: At

4 P.M. on April 17, 1864, an advanced Union patrol on the Washington Road was captured by Confederate cavalry. A company of

the 12th N.Y. Cavalry attacked the Confederates, but was repulsed. Soon a large force of Confederate infantry appeared on

the Washington Road, and at the same time Fort Gray, two miles above Plymouth on the river bank, was attacked by advanced

Confederate infantry.

During the evening, skirmishing continued from the Washington Road to the

Acre Road. Union General Henry W. Wessells’ garrison of about 3,000, which had held Plymouth since December, 1862, was

under attack by General Robert F. Hoke’s Division of over 5,000 men. (See also Battle of Plymouth and Operations against Plymouth.)

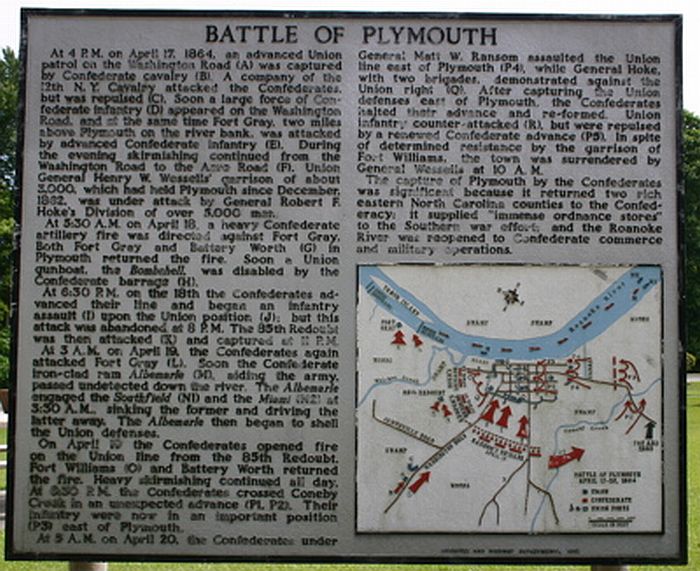

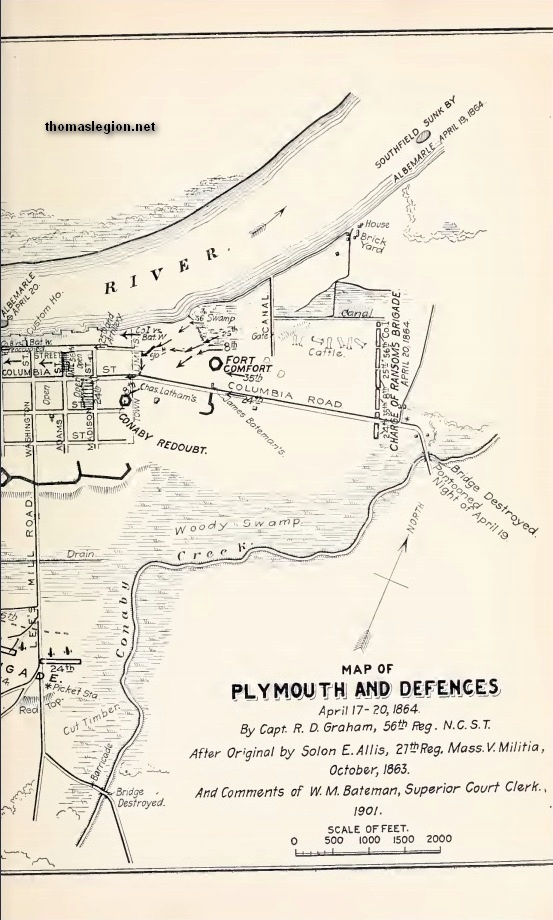

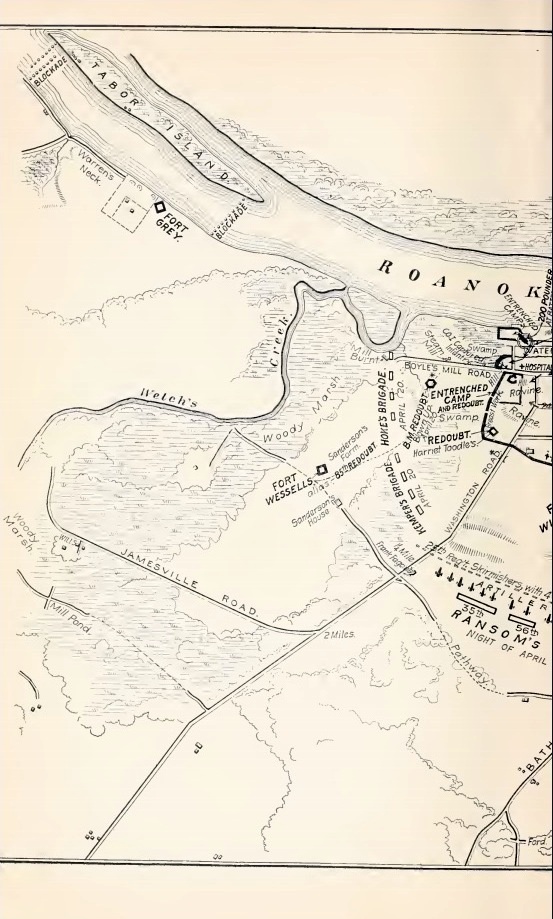

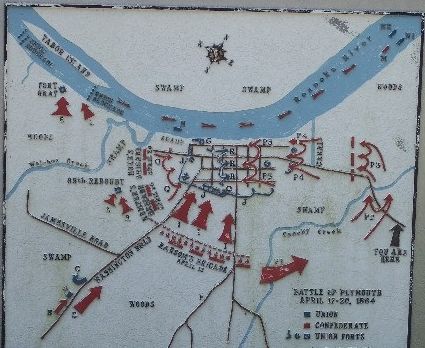

(About) Civil War-era Map of Plymouth, North Carolina, Defenses, April 17-20,

1864. Courtesy, Walter Clark, ed., Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great

War 1861-'65, Volume 5.

| Confederate General Hoke |

|

| (The Final Assault) |

| Battle of Plymouth |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

Union forces under the command of General Henry W. Wessells’

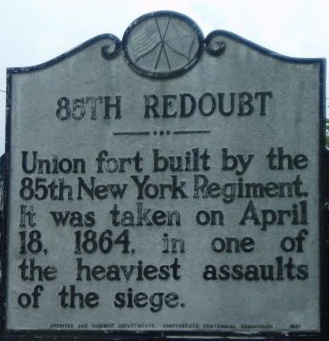

garrison of about 3,000 troops held Plymouth after the Federal occupation in December 1862. The 85th Redoubt, also known as

Fort Wessells and Fort

Williams, was an earthen fort built by the 85th New York

Regiment to maintain Union control of the region as part of a larger set of earthworks that ringed the town.

Armed with one 32 pound

and one 6 pound cannon, the fort was strategically placed and stood southwest of the main works. Although the earthworks protected

the town from both land and sea attacks, Confederates sought to retake the town in April 1864 and attacked the earthworks

from all quarters during the Battle of Plymouth.

At 5:30 A.M. on April 18, a heavy

Confederate artillery fire was directed against Fort Gray. Both Fort Gray and Battery Worth in Plymouth returned the fire.

Soon a Union gunboat, the Bombshell, was disabled by the Confederate barrage.

At 6:30 P.M. on the 18th the Confederates advanced their line and began

an infantry assault upon the Union position; but this attack was abandoned at 8 P.M. The 85th Redoubt was then attacked and

captured at 11 P.M.

At 3 A.M. on April 19, the Confederates again attacked Fort Gray. Soon the

Confederate ironclad ram Albemarle, aiding the army, passed undetected down the river.

Early on the morning of the 19th, the CSS Albemarle advanced into the battle. The ironclad had left its final construction

docks in Hamilton, maneuvered through channel obstructions, and easily withstood glancing blows of Union cannon from Fort

Gray outside of Plymouth before engaging ships in the Roanoke near the town. The

Albemarle successfully engaged and sank one Union gunboat and another left in retreat after suffering damage and the loss

of naval commander Charles W. Flusser. The Albemarle then bombarded the Union earthworks throughout the night.

| Battle of Plymouth |

|

| Battle of Plymouth |

| Confederate Ironclad Albemarle |

|

| (Historical Marker) |

| Confederate General Ransom |

|

| (Historical Marker) |

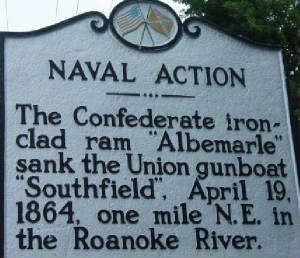

The Albemarle engaged the Southfield and the Miami at 3:30 A.M.,

sinking the former and driving the latter away. The Albemarle then began to shell the Union defenses.

On April 19 the Confederates opened fire on the Union line from the 85th

Redoubt. Fort Williams and Battery Worth returned the fire. Heavy skirmishing continued all day. At 6:30 P.M. the Confederates

crossed Coneby Creek in an unexpected advance. Their infantry were now in an important position east of Plymouth.

At 5 A.M. on April 20, the Confederates under General Matt W. Ransom assaulted

the Union line east of Plymouth, while General Hoke, with two brigades, demonstrated against the Union right. After capturing

the Union defenses east of Plymouth, the Confederates halted their advance and re-formed. Union infantry counter-attacked,

but were repulsed by a renewed Confederate advance. In spite of determined resistance by the garrison of Fort Williams, the

town was surrendered by General Wessells at 10 A.M. The capture of Plymouth

by the Confederates was significant because it returned two rich eastern North Carolina counties to the Confederacy; it supplied

“immense ordnance stores” to the Southern war effort; and the Roanoke River was reopened to Confederate commerce

and military operations. (See also Battle of Plymouth: In Their Own Words.)

| Plymouth and the Civil War |

|

| Battle of Plymouth |

| Confederate Civil War Flag |

|

| Civil War Battle of Plymouth, North Carolina. |

(About) Headquarters Flag of General Robert F. Hoke at the Battle of Plymouth. General Hoke and the Flag: A native of Lincolnton, North Carolina, General Robert F. Hoke

rose to the rank of major general during the Civil War. This is a second national pattern Confederate flag adopted on May

1, 1863 and used until replaced on March 4, 1865. Because of its large white field this pattern flag was nicknamed the "stainless

banner." This flag most certainly marked Hoke's headquarters during his brilliant victory at Plymouth, N.C., on April 20,

1864. This flag was donated to the state sometime after Hoke's death in 1912.

Casualties: Union casualties for the three day fight

at Plymouth were reported by Brig. Gen. Henry Wessells following his captivity and exchange in August 1864. While he

gave a detailed accounting of Federal losses, the Confederates did not. Union losses were reported at 2,834,

with 150-200 in killed or wounded. Confederate casualties were estimated

at 850 in killed or wounded.

The Raleigh Daily Confederate, May 3, 1864, published a total of 2437

Union prisoners as a result of the battle, and noted that Ransom's Brigade alone suffered 96 killed and 377 wounded. But while

this report gave totals, the Fayetteville Observer, May 9, reported specific losses for each unit forming Ransom's Brigade.

Casualty figures for Plymouth were also hearsay, such as one referenced by Union

Maj. Gen. John L. Peck, Headquarters, Army and District of North Carolina, New

Berne, N.C., April 24, 1864, when he reported that refugees picked up by the US gunboat Whitehead said that General Wessells

had lost about 400, while the enemy suffered not less than 1,500 killed and wounded.

Many present-day writings or accounts,

however, show total Confederate casualties for Plymouth at about 700 in killed, wounded or missing. Daniel W.

Barefoot, General Robert F. Hoke: Lee's Modest Warrior, states Confederate

losses at more than 160 killed and another 550 wounded, or 10% of Hoke's force; historychannel.com reports 717 casualties

with 163 killed and 554 wounded; Juanita Patience Moss, Battle of Plymouth, North Carolina (April 17-20, 1864), reports some

700 killed or wounded; Gregory J. W. Urwin, Black Flag Over Dixie: Racial Atrocities

and Reprisals in the Civil War, has 163 killed and 554 wounded, or 10% of Hoke's force. (See also Battle of Plymouth: In Their Own Words.)

(Sources) National Park Service; Library of Congress; N.C. Office

of Archives and History; northcarolinahistory.org; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Walter Clark, ed.

Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-'65, Volumes 1-5.

Recommended

Reading: Battle of Plymouth, North Carolina

(April 17-20, 1864): The Last Confederate Victory, by Juanita Patience Moss. Description: Are you familiar with the Battle of Plymouth? Not Plymouth, Massachusetts,

but how about Plymouth,

North Carolina? If you have never

heard of it, you are in the company of many others, even those who consider themselves avid Civil War buffs. The Battle of

Plymouth took place April 17-20, 1864, during the “Operations against Plymouth,”

and even though the engagement was one year before Lee surrendered to Grant, the sounds of America’s costliest and bloodiest conflict would yield havoc on

North Carolina’s

coastal communities. Continued below…

In

this fascinating book, you will read about the second largest battle in North Carolina

and it was fought at a small North Carolina coastal town

named Plymouth,

where the Confederates tasted their last victory. Intense action transpired during those four days, and the atmosphere was

filled with surprise, fate, intrigue, bravery, ingenuity, hope, daring, dedication, gallantry, victory, disappointment, and

defeat. The battle witnessed the likes of Cooke, Cushing, Flusser, Hoke, and Wessells, and the formidable CSS Albemarle, an

ironclad warship that was not built in the traditional shipyard, but rather in a Southern cornfield. The battle epitomized

the brothers’ war, with North Carolina Federal regiments fighting their North Carolina Confederate brethren; it also

witnessed African American regiments (USCT) in the thick of the fight. The combined Union

and Confederate casualties were just shy of 3,000, and the author offers an informative, enlightening, and interesting view

of the “Last Confederate Victory." Although a bit repetitive,

it is a worthy addition because it is the only full-length text dedicated to the battle. It is a welcome addition to North Carolina and school libraries, and to the buff that enjoys reading about the lesser-known Civil

War battles and it troops (Union and Confederate) that fought valiantly. Three stars.

Recommended Reading:

The Civil War in Coastal North Carolina (175 pages) (North Carolina Division

of Archives and History). Description: From the drama

of blockade-running to graphic descriptions of battles on the state's islands and sounds, this book portrays the explosive

events that took place in North Carolina's coastal region during the Civil War. Topics discussed include the strategic

importance of coastal North Carolina, Federal occupation

of coastal areas, blockade-running, and the impact of war on civilians along the Tar Heel coast.

Union setbacks in Virginia, however, led to the withdrawal of many federal soldiers from North Carolina,

leaving only enough Union troops to hold a few coastal strongholds—the vital ports and railroad junctions. The South

during the Civil War, moreover, hotly contested the North’s ability to maintain its grip on these key coastal strongholds.

Recommended Reading: Ironclads and Columbiads: The Coast (The Civil War in North Carolina)

(456 pages). Description: Ironclads and Columbiads

covers some of the most important battles and campaigns in the state. In January 1862, Union forces began in earnest to occupy

crucial points on the North Carolina coast. Within six months,

Union army and naval forces effectively controlled coastal North Carolina from the Virginia line south to present-day Morehead

City. Continued below...

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in North Carolina.

Description: Numerous battles and skirmishes were fought in North Carolina during the Civil War, and the campaigns and battles themselves were crucial

in the grand strategy of the conflict and involved some of the most famous generals of the war. John Barrett presents the

complete story of military engagements across the state, including the classical pitched battle of Bentonville--involving

Generals Joe Johnston and William Sherman--the siege of Fort

Fisher, the amphibious campaigns on the coast, and cavalry sweeps such

as General George Stoneman's Raid.

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in the Carolinas (Hardcover). Description: Dan Morrill relates the experience of two quite different states bound together in

the defense of the Confederacy, using letters, diaries, memoirs, and reports. He shows

how the innovative operations of the Union army and navy along the coast and in the bays and rivers of the Carolinas

affected the general course of the war as well as the daily lives of all Carolinians. He demonstrates the "total war" for

North Carolina's vital coastal railroads and ports. In

the latter part of the war, he describes how Sherman's operation

cut out the heart of the last stronghold of the South. Continued below...

The author

offers fascinating sketches of major and minor personalities, including the new president and state governors, Generals Lee,

Beauregard, Pickett, Sherman, D.H. Hill, and Joseph E. Johnston. Rebels and abolitionists, pacifists and unionists, slaves

and freed men and women, all influential, all placed in their context with clear-eyed precision. If he were wielding a needle

instead of a pen, his tapestry would offer us a complete picture of a people at war. Midwest Book Review: The Civil War in the Carolinas by civil war expert and historian

Dan Morrill (History Department, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and Director of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historical

Society) is a dramatically presented and extensively researched survey and analysis of the impact the American Civil War had

upon the states of North Carolina and South Carolina, and the people who called these states their home. A meticulous, scholarly,

and thoroughly engaging examination of the details of history and the sweeping change that the war wrought for everyone, The

Civil War In The Carolinas is a welcome and informative addition to American Civil War Studies reference collections.

Recommended Reading: Storm over Carolina: The Confederate

Navy's Struggle for Eastern North Carolina. Description: The struggle for control of the eastern waters of North Carolina during the War Between the States was a bitter, painful,

and sometimes humiliating one for the Confederate navy. No better example exists of the classic adage, "Too little, too late." Burdened

by the lack of adequate warships, construction facilities, and even ammunition, the South's naval arm fought bravely and even

recklessly to stem the tide of the Federal invasion of North Carolina from the raging Atlantic. Storm Over Carolina is the account of the

Southern navy's struggle in North Carolina waters and it

is a saga of crushing defeats interspersed with moments of brilliant and even spectacular victories. It is also the story

of dogged Southern determination and incredible perseverance in the face of overwhelming odds. Continued below...

For most of

the Civil War, the navigable portions of the Roanoke, Tar, Neuse, Chowan, and Pasquotank rivers were

occupied by Federal forces. The Albemarle and Pamlico sounds, as well as most of the coastal towns and counties, were also

under Union control. With the building of the river ironclads, the Confederate navy at last could strike a telling blow against

the invaders, but they were slowly overtaken by events elsewhere. With the war grinding to a close, the last Confederate vessel

in North Carolina waters was destroyed. William T. Sherman

was approaching from the south, Wilmington was lost, and the

Confederacy reeled as if from a mortal blow. For the Confederate navy, and even more so for the besieged citizens of eastern

North Carolina, these were stormy days indeed. Storm Over Carolina describes their story, their struggle, their history.

|