|

The Battle of the Alamo

Battle of the Alamo, Texas

| Battle of the Alamo, San Antonio |

|

| Battle of the Alamo, San Antonio, Texas |

Introduction

The Battle of the Alamo was a nineteenth

century battle between the Republic of Mexico

and the rebel Texan forces during the latter's fight for independence during the Texas Revolution, also known as the Texas War of Independence. It took place at the Alamo mission in San Antonio, Texas (then known as "San Antonio de Béxar")

in February and March of 1836. The 13-day siege ended on March 6 with the capture of the mission and the death of nearly all

the Texan defenders, except for a few slaves, women and children. Despite the loss, the 13-day holdout stalled Mexican forces'

progress and allowed Sam Houston to gather troops and supplies for his later successful battle at San

Jacinto. Approximately 189 defenders were attacked by about 4,000 Mexican soldiers.

The battle took place at

a turning point in the Texas Revolution, which had begun with the October 1835 Consultation whose delegates narrowly approved

a call for rights under the Mexican Constitution of 1824. By the time of the battle, however, sympathy for declaring a Republic of Texas had grown. The delegates from the Alamo to the Constitutional Convention were both instructed

to vote for independence. The deaths of such popular figures as Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie at the Alamo contributed to how

the siege has subsequently been regarded as an heroic and iconic moment in Texan and U.S.

history, notwithstanding that the Alamo fell. Texas' independence

and its eventual union with the U.S. would have been unlikely had Mexico succeeded in its plan to reassert sovereignty over the territory, which later would

contribute enormously to the U.S. economy.

| Battle of the Alamo, Texas |

|

| Battle of the Alamo, San Antonio, Texas |

The Fall of the Alamo (1903) by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, depicts Davy Crockett

wielding his rifle as a club against Mexican troops who have breached the walls of the mission.

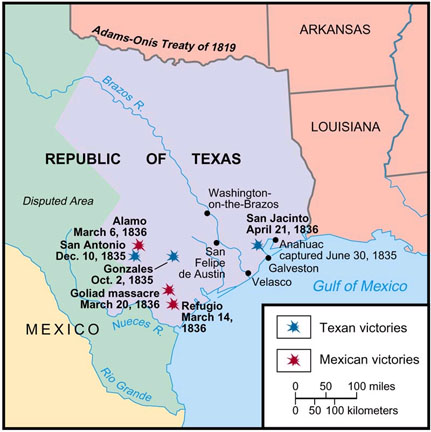

| Battle of the Alamo Map |

|

| Map of Texas Revolution, including Battle of the Alamo |

Prelude

Texas was part of the Mexican colony

of New Spain. After the Mexican independence in 1821, Texas

became part of Mexico. In 1824 it became

the northern section of Coahuila y Tejas. January 3, 1823, Stephen F. Austin began a colony of 300 American families along

the Brazos River in present-day Fort Bend County

and Brazoria County, primarily in the area

of what is now Sugar Land.

In

1835 the Mexican President and General Antonio López de Santa Anna Pérez de Lebrón, (known as Santa Anna or Antonio López de Santa Anna) abolished the Constitution of 1824 and proclaimed a new constitution that increased the power of the Presidency

and reduced the power of provincial governments. Since the end of hostilities with Spain

ten years before, the Mexican government generally and Santa Anna in particular, had been eager to reassert control

over entire country and control of Texas. This was seen

as important as Santa Anna perceived the province to be vulnerable to America's

westward expansion, which was in fact the case.

Mexico's

new interest in Texas was not popular with the colonists, who felt themselves to be more

economically and culturally linked to the United States than to Mexico. They were also used to the relative autonomy

they enjoyed under the old Constitution of 1824. Santa Anna's increasingly ambitious seizure of dictatorial powers under the

new constitution was causing unrest throughout Mexico.

Hostilities in Texas began with the Battle of Gonzales, October 1, 1835 after which Texan

rebels quickly captured Mexican positions at Goliad (La Bahía) and San Antonio.

After the surrender of General

Martín Perfecto de Cos and his garrison at San Antonio, there was no longer a Mexican military

presence in Texas. Santa Anna decided to launch an offensive

to put down the rebellion. Minister of War José María Tornel and Maj. Gen. Vicente Filisola (1789–1850) proposed a seaborne

attack to Santa Anna, which would have been easier for the troops. Since 1814, sea access had been the proven means of expeditions

into Texas. Santa Anna refused this plan because it would

take too long and, in the meantime, the rebels in Texas might receive aid from the United States.

Santa Anna assembled an

estimated force of 6,100 soldiers and 20 cannons at San Luis Potosí in early 1836 and moved

through Saltillo, Coahuila, towards Texas.

His army marched across the Rio Grande through inclemental

weather and snowstorms to suppress the rebellion. San Antonio de Béxar was one of his intermediate objectives; his ultimate

objective was to destroy the Texas government and to restore

rule of the central or "Centralist" Mexican government over a rebellious state. He had already suppressed a rebellion in the

state of Zacatecas in 1835.

Santa Anna and his army

arrived in San Antonio de Béxar on February 23, a mixed force of regular infantry and cavalry units and activo reserve infantry

battalions. They were equipped with British Baker and out-dated, short range but effective and deadly British Tower Musket,

Mark III, or "Brown Bess" muskets. The average Mexican soldier stood 5 feet, 1 inch; many were recent conscripts with no previous

combat experience. Although well-drilled, the Mexican army discouraged individual marksmanship. Initial forces were equipped

with four 7 inch howitzers, seven 4-pound, four 6-pound, four 8-pound, and two 12-pound cannons.

Many Mexican officers were

foreign mercenary veterans, including Vicente Filisola (Italy) and Antonio

Gaona (Cuba), while General Santa Anna

was a veteran of Mexican War of Independence.

| Battle of Alamo |

|

| Battle of the Alamo. state.tx.us. |

| Battle of the Alamo, San Antonio |

|

| Battle of the Alamo, Texas |

Defenders

Lieutenant Colonel William

Barret Travis now commanded the Texan regular army forces assigned to defend the old mission. In January 1836 he was ordered

by the provisional government to Alamo with volunteers to reinforce the 189 who were already there. Travis arrived in San Antonio on February 3 with 29 reinforcements. He became the post's official commander,

taking over from Col. James C. Neill, who promised to return in 20 days after leaving to tend to a family illness.

Other men also assembled

to help in the defensive effort, including a number of unofficial volunteers under the command of Jim Bowie. Travis and Bowie

often quarreled over issues of command and authority but as Bowie's

health declined, Travis assumed overall command. Bowie, after whom the "Bowie"

knife is named, was already famous for his adventures and knife fights.

At that time, the siege

of Alamo was seen as a battle of American settlers against Mexicans but many of the ethnic Mexicans in Texas (called Tejanos) in fact also sided with the rebellion. This struggle was viewed in

similar terms as the American Revolution of 1776. These Tejanos wanted Mexico

to have a loose central government and supported states rights as expressed in the Mexican Constitution of 1824. One Tejano

combatant at Alamo was Captain Juan Nepomuceno Seguín, who was sent out as dispatch rider

before the final assault.

Defenders of the Alamo came

from many places besides Texas. The youngest was Galba Fuqua,

16; one of the oldest was Gordon C. Jennings, 57. The men came from 28 different countries and states. From Tennessee, a small group of volunteers led by the famous hunter, politician and Indian fighter

Davy Crockett accompanied by Micajah Autry, a lawyer. A 12-man "Tennessee Mounted Volunteers" unit arrived at Alamo

on February 8. Davy Crockett had resigned from politics having told the electorate that if they did not elect him they could

go to hell and he would go to Texas!

The "New Orleans Greys,"

came from that city to fight as infantry in the revolution. The two companies comprising Greys had participated in the Siege

of Béxar in December. Most Greys then left San Antonio de Béxar for an expedition to Matamoros

with the promise of taking the war to Mexico, two dozen remaining at the

Alamo.

The abrogation of the Constitution

of 1824 was a key trigger for the revolt in general. Many white Anglo-Saxons in Texas had

strong sympathies for independence or for union with the United States.

Some may have wanted a return to the Old Constitution that had allowed them a large degree of self-determination. When the

Texans defeated the Mexican garrison at the Alamo in December of 1835, their flag had the words "Independence" on it. Letters written from Alamo expressed

that "all here are for independence." The famous letter from Travis referred to their "flag of Independence." Some 25 years after the battle, historian Reuben Potter claimed that reinstatement

of the Constitution of 1824 was a primary objective, and Potter's comments have also been the source of a myth that the battle

flag of the Alamo garrison was some sort of Mexican tricolor with "1824" on it.

Another main factor behind

the revolt was the fact that Santa Anna had abolished slavery in Mexico.

This was a serious setback to many landowners, who now faced financial ruin. Texan independence or joining the Union would allow these people to retain their slaves. As a slave state, Texas

would support the Confederate States of America

during the American Civil War.

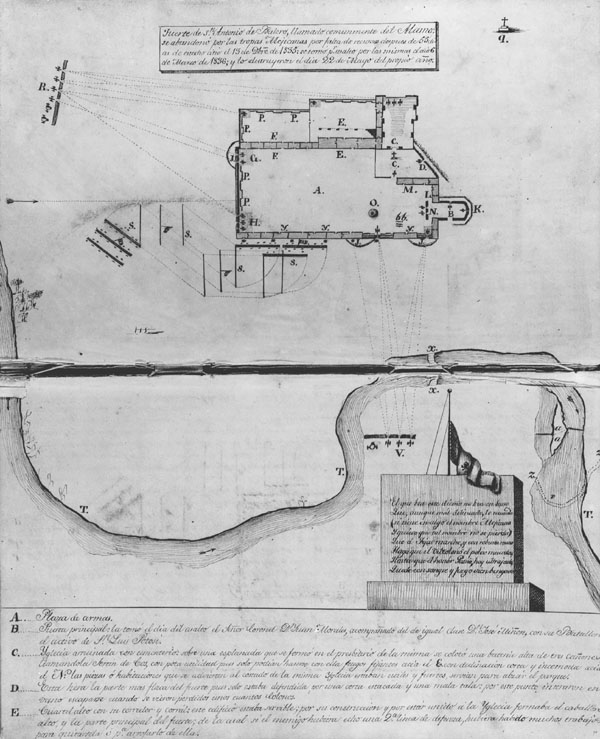

| Battle of the Alamo, San Antonio |

|

| Mexican Battle Plan for Alamo, Texas |

| Battle of the Alamo |

|

| Davy Crockett Battle of the Alamo |

(Right) This

attack plan for the Alamo was created by José Juan Sánchez-Navarro in 1836. Places marked R and V denote Mexican cannon; position

S indicates Cos's forces.

Siege

Lt. Col. William Travis

was able to dispatch riders before the battle of March 3 informing the Texas provisional government of his situation and requesting

assistance. Sam Houston's Texas Army was not strong enough to fight through the Mexican Army and relieve the post. The Provisional

Texas government was in disarray due to in-fighting among members. Travis sent several riders, including James Bonham (1808–1836),

to Colonel James Fannin for help. Fannin (1804–1836), commander of 450 Texas forces

at Goliad 100 miles southeast of Alamo, attempted an unorganized relief march with 320 men and cannon February 28 to Alamo, but aborted the relief column due to poor transportation. Most men were slaughtered by a Mexican

force after surrendering (the "Goliad Massacre").

March 1, 32 Texans led by

Capt. George Kimbell and John W. Smith from Gonzales, slipped through Mexican lines and joined the defenders inside the Alamo. They were the only response to Travis' plea for help. The group became known as the "Immortal

32." A letter written by one of the 32, Isaac Millsaps, details events inside Alamo on the

night before the siege.

Final assault

At the end of 12 days the

number of Mexican forces attacking was reported as high as 4,000 to 5,000, but only 1,400 to 1,600 soldiers engaged in

the final assault. Approximately 6,500 soldiers had originally set out from San Luis Potosí, but illness and desertion had reduced

the force. The Mexican siege was scientifically and professionally conducted in Napoleonic style. After 13-day period the

defenders were tormented with bands blaring at night (including buglers sounding the no-mercy call El Degüello), artillery

fire, an ever closing ring of Mexicans cutting off potential escape routes, Santa Anna planned the final assault for March

6. Santa Anna raised a blood red flag which made his message clear: No mercy would be given for defenders.

Lt. Col. Travis wrote in

his final dispatches: "The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion otherwise the garrison are to be put to the sword,

if the fort is taken—I have answered their demand with a cannon shot, & our flag still waves proudly from the walls—I

shall never surrender or retreat."

The Mexican army attacked

Alamo in four columns plus reserve and pursuit and security force, starting at 05:30 AM.

The first column of 300 to 400 men led by Martín Perfecto de Cos moved towards northwest corner of Alamo.

Second 380 men commanded by Col. Francisco Duque. Third column comprised 400 soldiers led by Col. José María Romero. Fourth

column comprised 100 cazadores (light infantry) commanded by Col. Juan Morales. The attacking columns had to cover 200 to

300 yards (200 to 300 m) open ground before they could reach Alamo walls. To prevent attempted

escape by fleeing Texans or reinforcements entering, Santa Anna placed 350 cavalry under Brig. Gen. Ramírez y Sesma to patrol

surrounding countryside.

Texans pushed back one of

the attacking columns but Perfecto de Cos' column was able to breach Alamo's weak north wall

quickly; the first defenders fell, among them William Barret Travis, who was killed by a shot to the head. The rest of Santa

Anna's columns continued the assault while Perfecto de Cos's men flooded into the fortress. Alamo's

defenders were spread too thin to adequately defend both the walls and the invading Mexicans. By 6:30 that morning, nearly

all Alamo defenders had been slain in brutal hand-to-hand combat. Famous defender Jim Bowie

is reported to have been bayoneted and shot to death in his cot. The battle, from initial assault to capture of the Alamo, lasted only an hour. A group of male survivors were executed after the battle, including, it

is claimed, Davy Crockett.

Victorious Mexicans released

two dozen surviving women and children, Bowie's slave Sam

and Travis' slave Joe after the battle. Joe spoke of seeing a slave named John killed in the Alamo

assault and another black woman killed. Another reported survivor was Brigido Guerrero, Mexican army deserter who had joined

the Texan cause. He was able to convince the Mexican soldiers that he had been a prisoner held against his will. Henry Wornell

was reportedly able to escape the battle, but died from his wounds three months later.

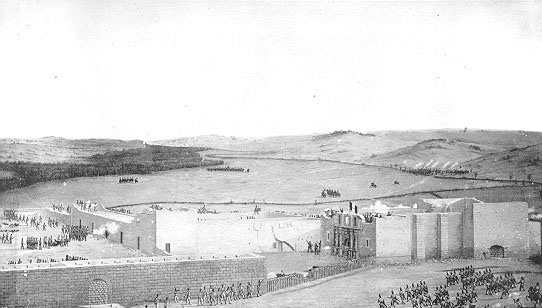

| Battle of the Alamo History |

|

| Battle of the Alamo, Texas |

(Right) Period portrait of the Alamo. "The Fall of the Alamo," painted by

Theodore Gentilz in 1844, depicts the Alamo complex from the south. The Low Barracks, the chapel, and the wooden palisade

connecting them are in the foreground.

Casualties

Texan: 183 to 250 Texan

and Tejano bodies were found at Alamo after the battle; Santa Anna's official report dictated to his personal secretary Ramón Martínez

Caro, stated 600 rebel bodies were found. Historians believe this to be a false claim. All but one were burned by the Mexicans;

the sole exception being Gregorio Esparza, who was buried rather than burned because his brother Francisco had served as an

activo who had fought under General Perfecto de Cos in Siege of Béxar.

Texan Independence

Texas declared independence on March 2. The delegates elected David G. Burnet as Provisional

President and Lorenzo de Zavala as Vice-President. The men inside the Alamo probably never

knew that this event had occurred. Houston still held his

rank of supreme military commander. The Texan Army never numbered more than 2,000 men at the time of Alamo

siege. Successive losses at Goliad, Refugio, Matamoros and

San Antonio de Béxar, reduced the army to 1,000 men.

April 21, at Battle of San

Jacinto, Santa Anna's 1,250-strong force was defeated by Sam Houston's army of 910 men, who used now-famous battle cry, "Remember

the Alamo!" Mexican losses for the day were 650 killed with 600 taken prisoner. Texan losses

were nine killed and 18 wounded. Santa Anna was captured the following day, dressed in a common soldier's jacket, having discarded

his finer clothing in hopes of escaping. He issued orders that all Mexican troops under the command of Vicente Filisola (1789–1850)

and José de Urrea (1795–1849) were to pull back into Mexico.

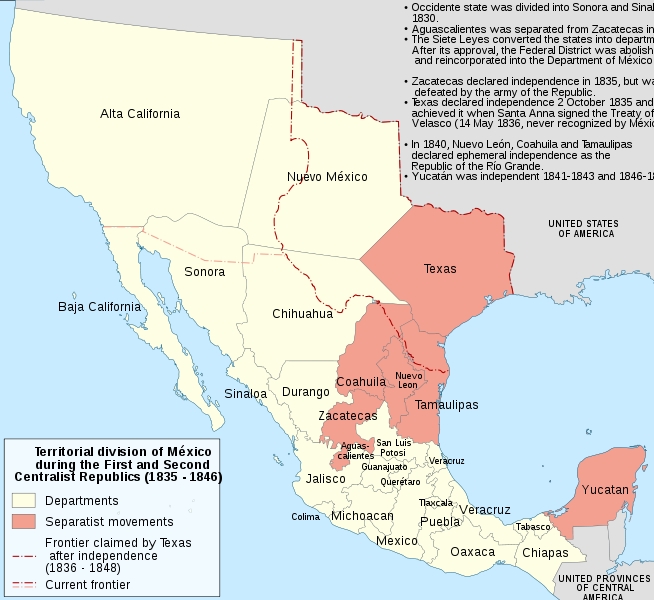

| Battle of the Alamo Map |

|

| Alamo Battle Map History |

Line in the sand

Legend has it that on March

3, 4, or March 5, Lt. Col. Travis drew a line in the sand with his sword inviting all those willing to stay, presumably to

die, to cross over the line. Jim Bowie was carried across the line at his request. All but one defender crossed the line.

Louis Rose, a French soldier who had fought under Napoleon in Russia before arriving in Texas, slipped

out of the Alamo. He evaded Mexican forces by moving at night, then Rose took shelter with

the family of William P. Zuber to whom he told the tale of his escape. In 1873, Zuber (his son) published a version of the

story, which has not been historically documented. The phrase "drawing a line in the sand" has remained part of English, for

taking a stand with no compromise. This account is narrated in Steven Kellerman's "The Yellow Rose of Texas," Journal of American

Folklore.

Before the war ended, Santa

Anna ordered a red flag be raised from San Fernando cathedral indicating to the defenders inside

the Alamo that no quarter would be given. According to José Enrique de la Peña's diary, several

defenders who had not been killed in the final assault on Alamo were captured by Col. Castrillón

and presented to Santa Anna, who personally ordered their deaths. Davy Crockett may or may not have been one of the six, since

this is disputed. De la Peña states that Crockett attempted to negotiate surrender with Santa Anna but was turned down on

the grounds of 'no guarantees for traitors'. There is little evidence to support this. Some believe that Crockett went down

struggling to stay alive when he was spotted by Santa Anna's army after the 12 day struggle.

Mexican Casualties

Santa Anna reported that he had

suffered 70 dead and 300 wounded, while many Texan accounts claim that as many as 1,500 Mexican lives were lost. While many

quickly dismiss Santa Anna's account as being unrealistic, Texan account of 1,500 dead also lacks logic.

Credit: "Battle of the Alamo." New World Encyclopedia. 2 Apr 2008, 03:06

UTC. 24 Feb 2009, 16:58 www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Battle_of_the_Alamo?oldid=678217

Recommended Reading: Texian

Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution.

Description: Hardly were the last shots fired at the Alamo before the Texas Revolution entered

the realm of myth and controversy. French visitor Frederic Gaillardet called it a "Texian Iliad" in 1839, while American Theodore

Sedgwick pronounced the war and its resulting legends "almost burlesque." In this highly readable history, Stephen L. Hardin

discovers more than a little truth in both of those views. Drawing on many original Texan and Mexican sources and on-site

inspections of almost every battlefield, he offers the first complete military history of the Revolution. Continued below…

From the war's opening in the "Come and Take It" incident at Gonzales to the capture of General Santa Anna

at San Jacinto,

Hardin clearly describes the strategy and tactics of each side. His research yields new knowledge of the actions of famous

Texan and Mexican leaders, as well as fascinating descriptions of battle and camp life from the ordinary soldier's point of

view. This in-depth coverage provides a balanced view of the Revolution that fairly assesses the conduct of both Texans and

Mexicans. Texian Iliad belongs on the bookshelf of everyone interested in Texas

or military history.

Review

Hardin has succeeded admirably

in writing a balanced military history of the revolution, making an important contribution to the extensive body of work on

the struggle that eventually led to Texas' becoming part of the United States.

Review

In Texian Iliad you smell

the smoke of battle. (Paula Mitchell Marks Texas Monthly

)

Hardin has succeeded admirably

in writing a balanced military history of the revolution, making an important contribution to the extensive body of work on

the struggle that eventually led to Texas' becoming part of the United States. (Mike Cox Austin American-Statesman )

Review

I

look forward to consulting this book for the rest of my career! (David J. Weber, Robert and Nancy Dedman Professor of History,

Southern Methodist University

)

Recommended Reading: Three

Roads to the Alamo: The Lives and Fortunes of David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Barret

Travis. Description: Ever since the day in March 1836 when an obscure Spanish mission in Texas

fell to Mexican forces led by President Santa Anna, Americans have been exhorted to "remember the Alamo."

And remember it we do--primarily as the place where American folk legends Davy Crockett, Jim Bowie, and William Travis met

their end fighting for Texas independence. Continued below…

Though it is primarily the

Alamo we remember today, the battle itself takes up just a few pages of William C. Davis's Three Roads to the Alamo; Davis

is far more interested in what brought three such disparate men as Crockett, Bowie, and Travis to Texas in the first place

than in how they died there. As any schoolchild knows, Davy Crockett was the "king of the wild frontier," a bona fide folk

hero in his own time who rode his legend to political office first in Tennessee and then as a United States

congressman. Bowie was both less well known and less heroic--a land speculator not above resorting to fraud and forgery to

get what he wanted, while William Travis, the youngest of the three, brought little but potential with him to Texas. Davis does a good job of illuminating both the

personalities of his subjects and the situation in which they found themselves in Texas.

He thoroughly explores the lives of these three men--their successes, their failures, their hopes for the future--and lays

out the arguments for and against Texan independence from Mexico

in which they found themselves embroiled. By the time Crockett, Bowie, and Travis finally arrive at the Alamo,

it seems the inevitable conclusion to the roads they each have been traveling over the course of their lifetimes. Three Roads

to the Alamo is a fine piece of historical research and an entertaining read, as well.

Recommended Viewing: The Alamo

(Widescreen Edition) (2004). Description: Despite a troubled production history including a switch in directors, budget overruns,

and delayed release dates, The Alamo turned out to be a remarkably intelligent mini-epic of corrective historical biography.

Dispensing with the grandiose myth-making of previous films on this subject (including John Wayne's gung-ho 1960 version),

this well-written film breathes new, credibly dimensional life into the stodgy legends of Davy Crockett (Billy Bob Thornton),

Jim Bowie (Jason Patric), and Lt. Col. William Travis (Patrick Wilson), who fought with 185 Anglo-"Texican" settlers (some

historians claim their numbers were closer to 250) during the bloody 13-day siege by 5,000 Mexican soldiers at the titular

San Antonio mission-turned-fortress in 1836. Continued below…

While Gen. Sam Houston (Dennis

Quaid) anguishes over military strategy and reluctantly withholds much-needed support, the Alamo defenders face the unbeatable

multitudes commanded by Mexican Gen. Santa Anna (Emilio Echevarria), and the screenplay (on which John Sayles was an early

contributor, when Ron Howard was slated to direct) allows the central heroes to reveal a richer, more substantial humanity

beneath their mythic reputations. Tackling his biggest production to date, director John Lee Hancock (who previously worked

with Quaid on The Rookie) reportedly shot 100 hours of footage, so it's almost miraculous that this 135-minute battle drama

is so evenly balanced in telling its oft-told tale. Thornton was deservedly singled out for his fine performance,

and Dean Semler's cinematography is Oscar-worthy throughout. Of course, any film about the Alamo

necessarily includes speculative history, and this one's no exception, but it's got a ring of truth that previous versions

conspicuously lacked. --Jeff Shannon

Recommended Reading:

A Time to Stand. Description: On the morning of March 6, 1836, in an

old abandoned mission called the Alamo, a small Texas garrison

fought to the death rather than yield to an overwhelming army of Mexicans. Through the years the garrison’s heroic stand

has become so clothed in folklore and romance that the truth has nearly been lost. In A Time to Stand Walter Lord rediscovers

and recreates the whole fascinating story. From contemporary documents, diaries, and letters, he has mined a wealth of fresh

information that throws intriguing sidelights on the epic of the Alamo. What were the defenders

like? Why did they take their stand? Did any escape? Did Davy Crockett surrender? Continued below…

The cast of characters includes

not only famous figures like Jim Bowie but unknown, unsung men: John Purdy Reynolds, the wandering Pennsylvania surgeon; George Kimball,

the industrious New York hatter, Micajah Autry of Tennessee,

who was a far better poet than a businessman. And then there are the Mexicans: the fabulous Santa Anna; the smooth Colonel

Almonte; the forlorn private Juan Basquez, who only wanted to stay home and make shoes. About the Author:

Walter Lord is the author of such bestsellers as A Night to Remember, Day of Infamy, and The Good Years: From Nineteen Hundred

to the First World War.

Recommended Reading: The

Gates of the Alamo. Description: A novel about the Alamo

promises as much suspense as a movie about the Titanic: we already know how it's going to end. The bloody siege of the Alamo

was, of course, not only the defining crisis in the Texan struggle for independence from Mexico but also an event that secured

martyrdom for the 200 or so men who died there and transformed a dusty Franciscan mission into a national shrine, an American

Troy. As with all mythologized chronicles, however, the Battle of the Alamo

ultimately resolves into mundane fact, a catalog of human error, ego, and heroism. And it is these details that Stephen Harrigan

regards in his broad and powerful third novel, The Gates of the Alamo. Continued below…

Passing lightly over the oft-profiled

Alamo stalwarts--Jim

Bowie, Davy Crockett, and the young commander William Travis--Harrigan focuses on fictional secondaries, primarily botanist

Edmund McGowan and mother and son Mary and Terrell Mott. Rigidly devoted to his work, Edmund straddles the fence in the dispute

over Texas, even as war murmurs grow. But when he meets

widowed Mary, who maintains her small inn with a steady, gentle resourcefulness, his good nature pulls him steadily into the

inevitable conflict. Mary herself is forced to quarter Mexican soldiers; and then, as she watches incredulously, her young

son seeks to test himself in the erupting skirmishes. Eventually the trio find themselves inside the Alamo

during the nearly two-week battle, their various conciliations frustrated by the surrounding mayhem. Harrigan's Texas is an

uncertain, dangerous jostling of peoples, a place where disaster threatens too frequently, where practical knowledge is paramount

and political ambivalence untenable, and where a primal beauty appears often as if by magic: "Hundreds and hundreds of lush

gray cranes ... spanned the sky almost from horizon to horizon, and the whole procession moved with the quiet, ordained manner

in which events unfold in a dream." However, the emblematic significance of the Alamo itself

remains inscrutable. As Mary tends to the dying, watching hope turn to hopelessness, she can only respond to Travis's rallying

orations with disillusionment: "She had heard enough of these empty patriotic effusions by now to feel that the Alamo was nothing but a sinking island of rhetoric." The Gates of the Alamo

nonetheless sweeps us into the many and variegated smaller stories that compose the larger one. It's a book to remember. --Ben

Guterson

Recommended Reading: The

Alamo (Bison Book). Description: "The majority of the stories of the

Alamo fight have been partly legendary, partly hearsay and at best fragmentary. It has been

left to John Myers Myers to present an exhaustively researched book which reveals the chronicle of the siege of the Alamo

in an entirely different light...Myers' story will stand as the best that has yet been written on the Alamo...It's a classic."-Boston

Post "Here is a historian with the vitality and drive to match his subject. A reporter of the first rank, he can clothe the

dry bones of history with the living stuff of which today's news is made."-Chicago Tribune John Myers Myers authored sixteen

books, including Doc Holliday and Tombstone's Early Years,

also available as Bison Books.

Recommended Reading: The

Illustrated Alamo 1836: A Photographic Journey [ILLUSTRATED] (Hardcover).

Description: The most iconic historic place in America

may also be the most misunderstood. For more than 170 years, the true nature and appearance of the Alamo, the cradle of Texas liberty, has eluded historians and artists alike. Partially demolished

soon after the famous battle, the mission/fortress's appearance grew more and more indistinct. Even more recently, Hollywood has itself compounded the problem by redesigning the place

to suit the artistic purposes of the dramatic script. Continued below…

But the truth was lurking all

along, in old sketches, plats, diagrams, and later archaeological digs. Now for the first time, all of the available sources

have been meticulously consulted and brought together to create the most accurate illustrated book on the true appearance

of the Alamo

in 1836 ever produced. The reader is taken through the entire compound, inside and out, room to room, and shown areas never

before depicted. For clarity, the compound is divided into sectors, each chapter covering a sector, which is then explored

in detail. Through extremely realistic photo-illustrations, as well as dramatic original artwork with explanatory text, the

author breathes new life into the 1836 Alamo, and makes it real. Scholars, students, artists,

and readers of history all will find this a fascinating journey back in time.

Recommended Reading: Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions [ILLUSTRATED] (Paperback). Description:

After 15 years of meticulous research, Thomas Ricks Lindley presents his masterpiece Alamo Traces. He dispels the abundance

of myth and folklore surrounding the events that took place at the Alamo and focuses on describing

a factual and honest account of the fight for independence. A critical examination of truth and fiction, coupled with a piece-by-piece

dismantling of what we thought we knew, results in an extremely accurate description of this famed event in American history.

Continued below…

About the Author:

Thomas Ricks Lindley is a former Army military policeman and criminal investigator. He has published numerous articles in

The Alamo Journal, the publication of The Alamo Society. Currently working on a manuscript about the relationship between

Sam Houston and Andrew Jackson, the author resides in Austin, Texas.

Recommended Reading: The

Alamo 1836: Santa Anna's Texas Campaign.

Description: On the morning of 6 March 1836 around 1,100 Mexican soldiers under Generalissimo Santa Anna stormed a small mission

outside San Antonio, Texas,

and slaughtered the garrison of around 200 Texans. It was not a large battle but its significance vastly outweighed its size

for the name of the mission was the Alamo. Less than two months later Santa Anna's force

was smashed at San Jacinto by a volunteer army whose battle cry was "Remember the Alamo".

Stephen L Hardin details the climactic 1836 campaign which won Texas

her independence. Continued below…

From the Publisher: Highly visual

guides to history's greatest conflicts, detailing the command strategies, tactics, and experiences of the opposing forces

throughout each campaign, and concluding with a guide to the battlefields today.

Recommended Reading:

Eighteen Minutes: The Battle of San Jacinto and the Texas Independence Campaign

(544 pages). Description: A great overview of the Texas Revolution, troops movements and motivations. The often told story

of the climatic battle of San Jacinto [make that "San Haceento" not "San Yacinto"] is riveting.

The small band of distraught and angry Texas survivors refuses

to retreat further. Houston is forced to make the best of

a bad situation and is forced to fight. Continued below…

Santa Ana

was never worried. He'd whipped the Texans at Alamo. He'd butchered them at Goliad--and--the

remaining Texans were running like scalded cats. Only worried that the Texas

rebels might escape his vengeful hand, he splits his force into a three-prong dragnet. The morning the Texas

forces show up, finds Santa Ana and his small army of regulares

backed against the Buffalo Bayou. The General is so unconcerned, some recollections have it, that he was entertaining himself

with a mulatto girl he'd picked up at one of the local plantations. This is the famous "Yellow Rose" of Texas song and legend. She gave her all for Texas and Santa Ana was caught with his pants down. The enraged Texans break the

Mexican line screaming, "Remember Goliad! Remember the Alamo!" They remembered in blood.

Pleading Mexican soldiers are backed into the bayou where they are shot, clubbed and knifed. Hatred between Texas

and Mexico--hatred warmed at Alamo and heated at Goliad--came to a fatal

boil at San Jacinto. The great Generalissimo-Presidente de Mexico, Antonio Lopez de Santa,

when offered the choice between hanging from an oak tree and signing away Texas, chose the latter or, as Col. Enrique de la

Pena said, "Travis was a land-thief and criminal but he gave his life for his country. Santa

Ana, when given the opportunity of dying like a Mexican hero, decided to save his own cowardly neck."

Ron Braithwaite, author of novels--"Skull Rack" and "Hummingbid God"--on the Conquest of

Mexico

Further Reading:

Barr, Alwyn (1996), Black Texans:

A history of African Americans in Texas, 1528–1995 (2nd ed.), Norman, OK: University of

Oklahoma Press; Chariton, Wallace O. (1990), Exploring the Alamo Legends, Dallas,

TX: Republic of Texas Press; Edmondson, J.R. (2000), The Alamo Story-From History to Current Conflicts, Plano, TX: Republic

of Texas Press; Glaser, Tom W. (1985), Schoelwer, Susan Prendergast, ed., Alamo Images: Changing Perceptions of a Texas Experience,

Dallas, TX: The DeGlolyer Library and Southern Methodist University Press; Groneman, Bill (1990), Alamo Defenders, A Genealogy:

The People and Their Words, Austin, TX: Eakin Press; Groneman, Bill (1996), Eyewitness to the Alamo, Plano, TX: Republic of

Texas Press; Groneman, Bill (1998), Battlefields of Texas, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press; Hardin, Stephen L. (1994),

Texian Iliad, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; Hopewell, Clifford (1994), James Bowie Texas Fighting Man: A Biography,

Austin, TX: Eakin Press; Lindley, Thomas Ricks (2003), Alamo Traces: New Evidence and New Conclusions, Lanham, MD: Republic

of Texas Press; Lord, Walter (1961), A Time to Stand, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; Manchaca, Martha (2001),

Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans, The Joe R. and Teresa Lozano

Long Series in Latin American and Latino Art and Culture, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; Myers, John Myers (1948),

The Alamo, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; Nofi, Albert A. (1992), The Alamo and the Texas

War of Independence, September 30, 1835 to April 21, 1836: Heroes, Myths, and History, Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, Inc.;

Petite, Mary Deborah (1999), 1836 Facts about the Alamo and the Texas War for Independence, Mason City, IA: Savas Publishing

Company; Schoelwer, Susan Prendergast (1985), Alamo Images: Changing Perceptions of a Texas Experience, Dallas, TX: The DeGlolyer

Library and Southern Methodist University Press; Scott, Robert (2000), After the Alamo, Plano, TX: Republic of Texas Press;

Tinkle, Lon (1985), 13 Days to Glory: The Siege of the Alamo, College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. Reprint.

Originally published: New York: McGraw-Hill, 1958; Todish, Timothy J.; Todish, Terry; Spring, Ted (1998), Alamo Sourcebook,

1836: A Comprehensive Guide to the Battle of the Alamo and the Texas

Revolution, Austin, TX: Eakin

Press.

|