|

Battle of the Crater History

Battle of the Crater, or Battle of the Mine

American Civil War Battle of the Crater, July 30, 1864

The Battle of the Crater

July 30, 1864

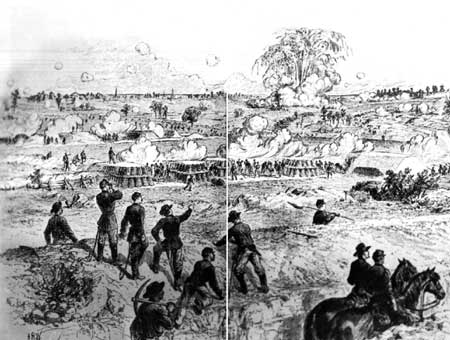

After weeks of preparation, on July 30 the Federals exploded a mine in Burnside’s

IX Corps sector beneath Pegram’s Salient, blowing a gap in the Confederate defenses of Petersburg. From this propitious

beginning, everything deteriorated rapidly for the Union attackers. Unit after unit charged into and around the crater, where

soldiers milled in confusion. The Confederates quickly recovered and launched several counterattacks led by Maj. Gen. William

Mahone. The break was sealed off, and the Federals were repulsed with severe casualties. Ferrarro’s division of black

soldiers was badly mauled. This may have been Grant’s best chance to end the Siege of Petersburg. Instead, the soldiers

settled in for another eight months of trench warfare. Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside was relieved of command for his role

in the debacle.

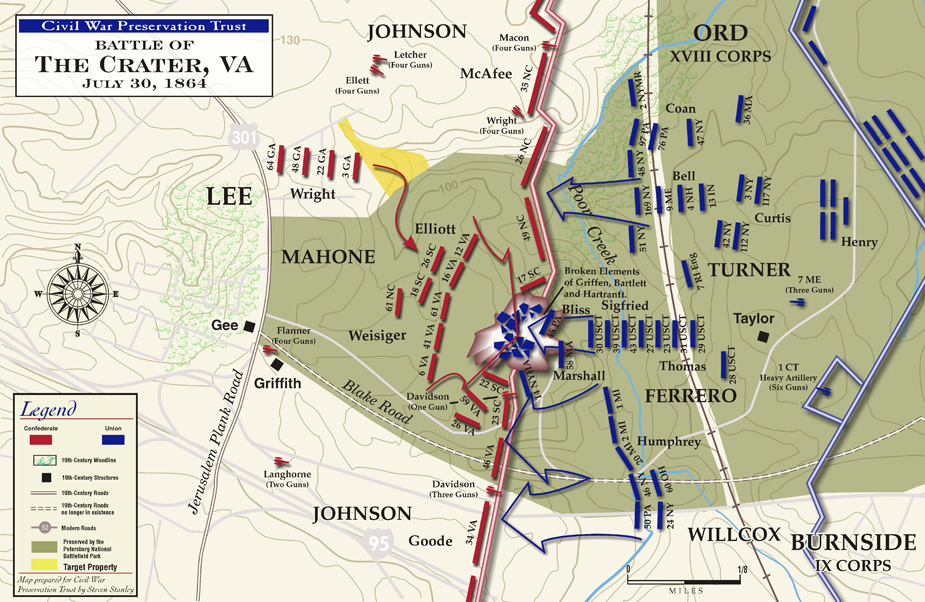

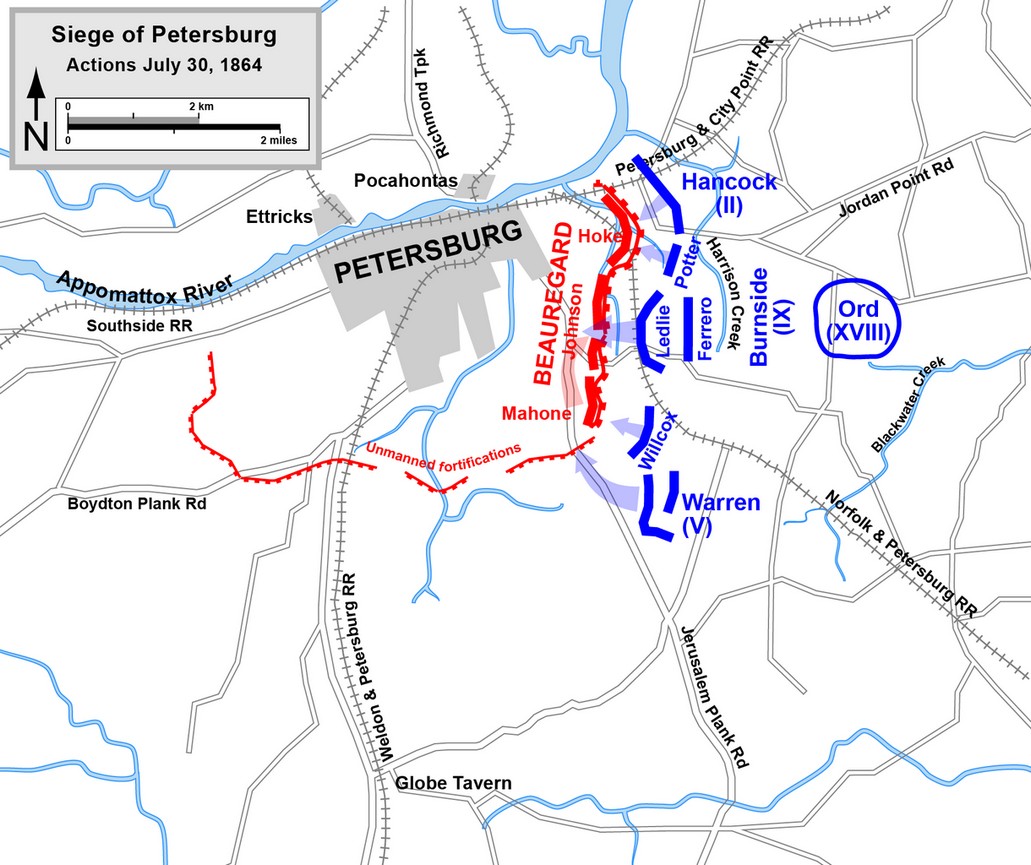

| Battle of the Crater, Petersburg, Civil War Map |

|

| Battlefield Map of Union and Confederate Troop Positions at the Crater |

(About) Map of Union and Confederate

lines in Petersburg trenches on July 30, 1864, with Union Mine explosion under Confederate position,

thus causing massive “Crater”, and then direction of Union advance and engagement with Confederate units. Click

to enlarge. Map courtesy Civil War Preservation Trust.

At several places east of the city the opposing lines were extremely close together. One of these locations

was in front of Elliott's Salient, a Confederate strong point near Cemetery Hill and old Blandford Church. Here the Confederate position and the Union picket line were less than 400 feet

apart. Because of the proximity of the Union line, Elliott's Salient was well fortified. Behind earthen embankments was a

battery of four guns, and two veteran South Carolina infantry

regiments were stationed on either side. Behind these were other defensive works; before them the ground sloped gently downward

toward the Union advance line.

This forward Union line was built on the crest of a ravine which had been crossed on June 18. Through this

ravine, and between the sentry line and the main line, lay the roadbed of the Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad. The front in this sector

was manned by Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's IX Corps. Among the many units which composed this corps was the 48th Regiment, Pennsylvania

Veteran Volunteer Infantry. A large proportion of this regiment had been coal miners, and it seemed to have occurred to one

or more of them that Elliott's Salient would provide an excellent place to use their civilian occupation. Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants,

the commanding officer of the 48th and a mining engineer by profession, overheard one of the enlisted men mutter, "We could

blow that damned fort out of existence if we could run a mine shaft under it." From this and similar remarks came the germ

of the idea for the Union mine. This is what the 48th Regiment proposed to do: dig a long

gallery from the bottom of the ravine behind their picket line to a point beneath the Confederate battery at Elliott's Salient,

blow up the position by means of powder placed in the end of the tunnel, and, finally, send a strong body of troops through

the gap created in the enemy's line by the explosion. They saw as the reward for their effort the capitulation of Petersburg and, perhaps, the end of the war.

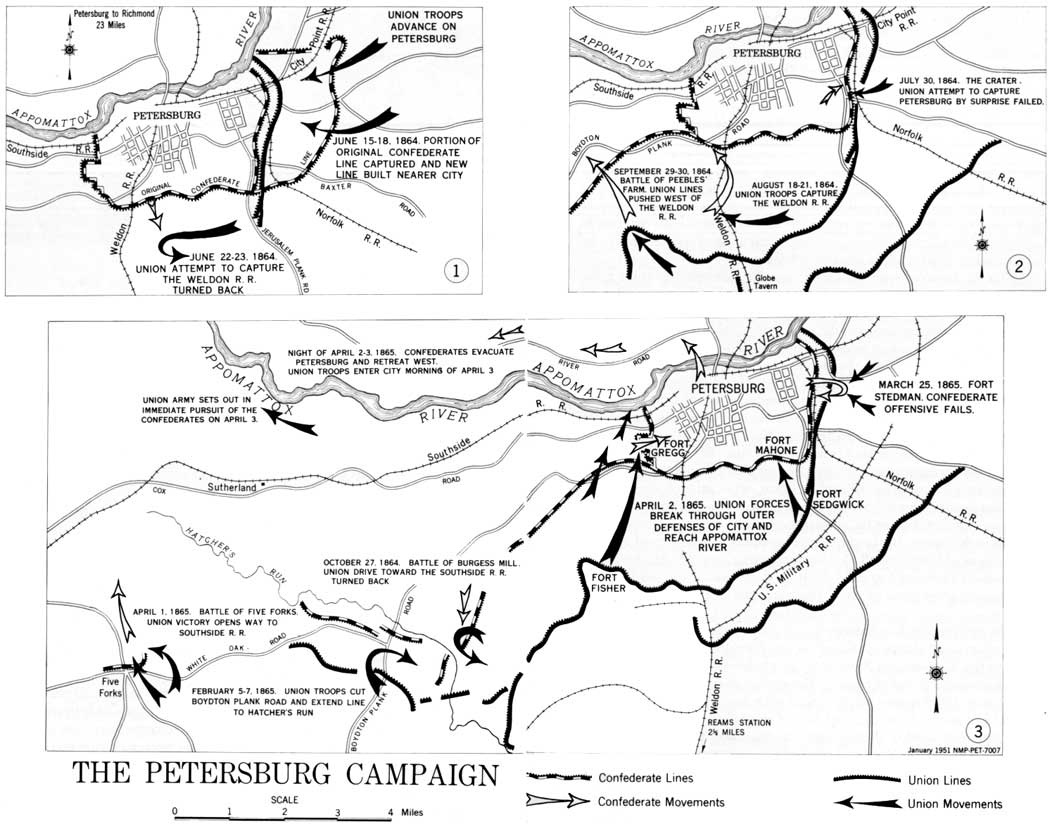

| Battle of the Crater Map |

|

| Civil War Petersburg Campaign Map of Battlefields |

| Civil War Trenches of Petersburg, Virginia |

|

| Union siege line and trench around Petersburg |

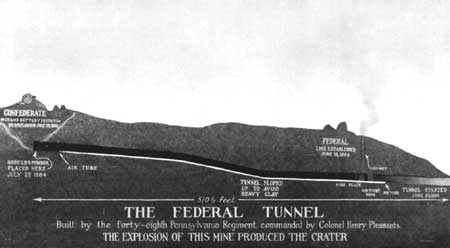

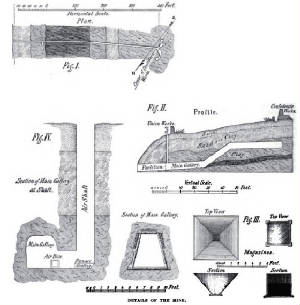

| Union Tunnel to the Mine at Petersburg, Civil War |

|

| Explosion of Federal Mine produced the massive "Crater" |

(Above) Built by the 48th Pennsylvania Regiment, the long shaft served

as host to the immense amount of gunpowder that caused the crater at Petersburg. The mine was not altogether unique, however.

At Vicksburg, during the previous July in 1863, a similar yet smaller mine was detonated under the 3rd Louisiana Redan during

Grant's Siege of Vicksburg. The large abyss at Petersburg was considerably larger than the Vicksburg crater that had been

caused by some 2,200 pounds of gunpowder. While the massive crater at Petersburg was the result of 8,000 lbs. of gunpowder,

it was also unique because black troops spearheaded the disastrous advance into

the large pit. Both mines had eerily familiar outcomes: Union men had advanced only to be repulsed, and neither event had

any material impact on its battle.

After obtaining the permission

of Burnside and Grant, Pleasants and his men commenced digging their mine shaft on June 25. The lack of proper equipment

made it necessary constantly to improvise tools and apparatus with which to excavate. Mining picks were created from straightened

army picks. Cracker boxes were converted into hand barrows in which the dirt was removed from the end of the tunnel. A sawmill

changed a bridge into timber necessary for shoring up the mine. Pleasants estimated both direction and depth of the tunnel

by means of a theodolite (old-fashioned even in 1864) sent him from Washington. The outmoded instrument served its purpose

well, however; the mine shaft hit exactly beneath the salient at which it was aimed.

Recommended Reading: Into the Crater: The

Mine Attack at Petersburg, by Earl J. Hess. Description: The battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864, was

the defining event in the 292-day campaign around Petersburg, Virginia, in the Civil War and one of the most famous engagements

in American military history. Although the bloody combat of that "horrid pit" has been recently revisited as the centerpiece

of the novel and film versions of Charles Frazier's Cold Mountain, the battle has yet to receive a definitive historical study.

Distinguished Civil War historian Earl J. Hess fills that gap in the literature of the Civil War with Into the Crater. Continued

below...

The Crater was central in Ulysses S. Grant's third offensive at Petersburg and required digging of a five-hundred-foot

mine shaft under enemy lines and detonating of four tons of gunpowder to destroy a Confederate battery emplacement. The resulting

infantry attack through the breach in Robert E. Lee's line failed terribly, costing Grant nearly four thousand troops, among

them many black soldiers fighting in their first battle. The outnumbered defenders of the breach saved Confederate Petersburg

and inspired their comrades with renewed hope in the lengthening campaign to possess this important rail center. In this narrative

account of the Crater and its aftermath, Hess identifies the most reliable evidence to be found in hundreds of published and

unpublished eyewitness accounts, official reports, and historic photographs. Archaeological studies and field research on

the ground itself, now preserved within the Petersburg National Battlefield, complement the archival and published sources.

Hess re-creates the battle in lively prose saturated with the sights and sounds of combat at the Crater in moment-by-moment

descriptions that bring modern readers into the chaos of close range combat. Hess discusses field fortifications as well as

the leadership of Union generals Grant, George Meade, and Ambrose Burnside, and of Confederate generals Lee, P. G. T. Beauregard,

and A. P. Hill. He also chronicles the atrocities committed against captured black soldiers, both in the heat of battle and

afterward, and the efforts of some Confederate officers to halt this vicious conduct.

One of the most remarkable features of the gallery was the method devised

to supply the diggers at the end with fresh air. The longer the tunnel grew, the more serious became the problem of ventilation.

It had been considered impossible to dig a tunnel for any considerable distance without spacing shafts at regular intervals

in order to replace the polluted air with a fresh supply. This problem had been solved by the application of the simple physical

principle that warm air tends to rise. Behind the Union picket line and to the right of the mine gallery, although connected

with it, the miners dug a ventilating chimney. Between the chimney and the mine entrance they erected an airtight canvas door.

Through that door and along the floor of the gallery there was laid a square wooden pipe. A fire was then built at the bottom

of the ventilating shaft. As the fire warmed the air it went up the chimney. The draft thus created drew the bad air from

the end of the tunnel where the men were digging. As this went out, fresh air was drawn in through the wooden pipe to replace

it.

| Union Soldiers in Petersburg Trench |

|

| Union Soldiers in Petersburg Trench |

(About) Photograph of Union soldiers in trench at Petersburg and prior to

the advance into the infamous Crater. Library of Congress.

Work on the tunnel had been continuously pushed from the start on June

25. By July 17 the diggers were nearly 511 feet from the entrance and directly beneath the battery in Elliott's Salient. The

Confederates had become suspicious by this time, for the faint sounds of digging could be heard issuing from the earth. Their

apprehension took the form of countermines behind their own lines. Several of these were dug in an effort to locate the Union

gallery. Two were very close, being sunk on either side of where the Pennsylvanians were at work. Although digging in the

countermines continued throughout the month of July, Confederate fears seemed to quiet down during the same period. There

were many reasons for this. One was the failure of their tunnels to strike any Union construction. Another major reason, undoubtedly,

was a belief held by many that it was impossible to ventilate a shaft of any length over 400 feet without constructing air

shafts along it.

The next step in the Union plan was to burrow out into lateral galleries

at the end of the long shaft. Accordingly, on July 18 work was begun on these branches which extended to the right and left,

paralleling the Confederate fortifications above. When completed, these added another 75 feet to the total length of the tunnel

which now reached 586 feet into the earth. It was about 20 feet from the floor of the tunnel to the enemy works above. The

average internal dimensions of the shaft were 5 feet high, with a base 4 1/2 feet in width tapering to 2 feet at the top.

Digging was finally completed on July 23. Four days later the task of

charging the mine with black powder was accomplished. Three hundred and twenty kegs of powder weighing, on the average, 25

pounds each were arranged in the two lateral galleries in eight magazines. The total charge was 4 tons, or 8,000 pounds. The

powder was sandbagged to direct the force of the explosion upward and two fuses were spliced together to form a 98-foot line.

Meanwhile, preparations for the attack which was to follow the explosion

of the mine had been carried out. Burnside was convinced of the necessity for a large-scale attack by the entire IX Corps.

His request was acceded to by Meade and Grant with but one important exception. It had been Burnside's hope that a fresh and

numerically strong (about 4,300) Negro division should lead the charge after the explosion. Meade opposed this on the grounds

that if the attack failed the Union commanders could be accused of wanting to get rid of the only Negro troops then with the

Army of the Potomac.

Burnside was not informed of this decision until the day before the battle, July 29, and he was forced to change his plans

at the last moment. Three white divisions were to make the initial charge along with the colored troops. Burnside had the

commanding generals of these three divisions draw straws to see which would lead. Gen. James F. Ledlie of the 1st Division

won the draw.

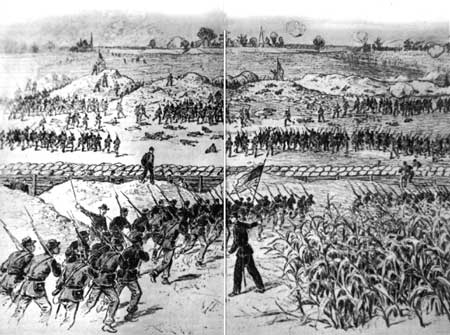

| From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. |

|

| Sketch by Waud showing Union charge to Crater. |

| From Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. |

|

| Explosion of Union Mine recorded by A.R. Waud. |

| Civil War Crater, July 30, 1863 |

|

| Civil War Battle of the Crater Battlefield Map |

Despite these eleventh-hour changes, a plan of battle had been evolved. During

the night of July 29—30 the bulk of the IX Corps had assembled in the ravine behind the mine entrance. Troops from other

Union corps were sent to act as reinforcements. A total of 110 guns and 54 mortars was alerted to begin their shelling of

the Confederate line. A Union demonstration before Richmond had forced Lee to withdraw troops from Petersburg.

Only about 18,000 soldiers were left to guard the city.

At 3:15 a. m., July 30, Pleasants lit the fuse of the mine and mounted the

parapet to see the results of his regiment's work. The explosion was expected at 3:30 a. m. Minutes passed slowly by, and

the men huddled behind the lines grew more apprehensive. By 4:15 there could be no doubt but that something had gone wrong.

Two volunteers from the 48th Regiment (Lt. Jacob Douty and Sgt. Harry Reese) crawled into the tunnel and found that the fuse

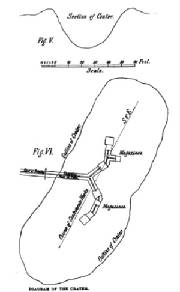

had burned out at the splice. They relighted it and scrambled to safety. Finally, at about 4:45 a. m., the explosion took

place. The earth trembled as men, equipment, and debris were hurled high into the air. At least 278 Confederate troops were

killed or wounded in the tremendous blast, and 2 of the 4 guns in the battery were destroyed beyond repair. The measurements

of the size of the crater torn by the powder vary considerably, but it seems to have been at least 170 feet long, 60 to 80

feet wide, and 30 feet deep.

| Battle of the Mine & Crater Diagram |

|

| (Civil War Virginia Crater Battlefield) |

| Battle of the Crater & Explosion Diagram |

|

| (Civil War Crater Battle Plan and Attack Map) |

(About) (L) Battle of the Crater: Details of the Crater; (R) Battle

of the Crater: Diagram of the Mine. Courtesy Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume 4, pp. 548-549.

The awesome spectacle of the mine explosion caused a delay in the Union

charge following the explosion. Removal of obstructions between the lines caused further delay. Soon, however, an advance

was made to the crater where many of the attacking force paused to seek shelter on its steep slopes or to look at the havoc

caused by the mine. The hard-pressed Confederates tallied quickly and soon were pouring shells and bullets into their opponents.

Union reinforcements poured into the breach; but, instead of going forward, they either joined their comrades in the crater

or branched out to the immediate right and left along the lines. By 8:30 that morning a large part of the IX Corps had been

poured into the captured enemy salient. Over 15,000 troops now filled and surrounded the crater.

By prompt action and determined effort the Confederates had stopped

the attack. The attention of three batteries was soon directed on the Blue-clad men in the crater. Repeated volleys of artillery

shot and shell raked the huddled groups of increasingly demoralized men. In addition, mortars were brought to within 50 yards

of the crater and started to drop shells on the soldiers with deadly effect.

Successful as these devices were in halting the Union advance, Lee was

aware that an infantry charge would be necessary to dislodge the enemy. By 6 a. m. an order had been sent to General Mahone

to move two brigades of his division from the lines south of Petersburg to the defense of the threatened position. Then

Lee joined Beauregard in observing the battle from the Gee house, 500 yards to the rear of the scene of strife.

| The Crater as it appeared in 1865. |

|

| The Crater at Petersburg as it appeared in 1865. |

In spite of the Confederate resistance,

most of the Northern Negro division and other regiments had, by 8 a. m., advanced a short distance beyond their companions

at the crater. Shortly after 8 o'clock Mahone's Confederate division began to arrive on the scene. The men fled into a ravine

about 200 yards west of the crater and between it and Petersburg. No sooner had they entered this protected position

than, perceiving the danger to their lines, they charged across the open field into the mass of enemy soldiers. Although outnumbered,

they forced the Northerners to flee back to the comparative shelter of the crater. Then they swept on to regain a portion

of the line north of the Union-held position. Again, at about 10:30 a. m., more of Mahone's troops charged, but were repulsed.

Meanwhile, the lot of the Northern soldiers was rapidly becoming unbearable. The spectacle within the crater was appalling.

Confederate artillery continued to beat upon them. The closely packed troops (dead, dying, and living mixed indiscriminately

together) lacked shade from the blazing sun, food, water and, above all, competent leadership. Meade had ordered their withdrawal

more than an hour before the second Confederate charge, but Burnside delayed the transmission of the order till after midday.

Many men had chosen to run the gantlet of fire back to their own lines, but others remained clinging to the protective sides

of the crater.

The last scene in the battle occurred shortly after 1 p. m. A final

charge by Mahone's men was successful in gaining the slopes of the crater. Some of the Union men overcome with exhaustion

and realizing the helplessness of their situation, surrendered; but others continued to fight. At one point where resistance

centered, the Confederates put their hats on ramrods and lifted them over the rim of the crater. The caps were promptly torn

to shreds by a volley. Before their foe could reload, Mahone's forces jumped into the

crater where a desperate struggle with bayonets, rifle butts, and fists ensued.

Soon it was all over. The Union Army had suffered a loss of some 4,000

in killed, wounded, captured or missing versus approximately 1,500 for the Confederates. Again, as on June 15—18,

a frontal assault had failed to take the Confederate citadel. Continue to Battle of the Crater: Overview, Timeline, Maps and Battlefield Positions.

(Sources listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended Reading: Battle of the Crater (Civil War Campaigns and Commanders).

Description: July 1864. Grant's siege of Petersburg is at

a standstill. A Federal regiment made up mostly of Pennsylvania

coal miners, under the command of Lt. Colonel Henry Pleasants, secures the reluctant approval of Generals Meade and, ultimately,

Grant to pursue an outrageous strategy: tunnel under the Confederate trenches, and blow up the Confederate troops. The 586-foot

tunnel is completed in a month. Continued below.

Four tons of powder explode in

a devastating surprise attack, killing hundreds of Confederate soldiers. Fearing bad publicity, white soldiers are substituted

for the division of black troops specially trained for the assault. Ill prepared, and without leadership, they charge through

Confederate lines and swarm around and incredibly, into the 170-foot crater, only to be trapped and slaughtered in a furious

counter charge. An absorbing story of extraordinary bravery and incompetent leadership based on first-person accounts.

Recommended Reading: No Quarter: The Battle

of the Crater, 1864.

Description: In this richly researched and dramatic work of military history, eminent historian Richard Slotkin recounts one

of the Civil War’s most pivotal events: the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. At first glance, the Union’s plan seemed brilliant: A regiment of miners would burrow beneath a Confederate fort,

pack the tunnel with explosives, and blow a hole in the enemy lines. Then a specially trained division of African American

infantry would spearhead a powerful assault to exploit the breach created by the explosion. Continued below.

Thus, in one

decisive action, the Union would marshal its mastery of technology and resources, as well as demonstrate the superior morale

generated by the Army of the Potomac’s embrace of emancipation. At stake was the chance

to drive General Robert E. Lee’s Army of North Virginia away from the defense of the Confederate capital of Richmond–and

end the war. The result was something far different. The attack was hamstrung by incompetent leadership and political infighting

in the Union command. The massive explosion ripped open an immense crater, which became a death trap for troops that tried

to pass through it. Thousands of soldiers on both sides lost their lives in savage trench warfare that prefigured the brutal

combat of World War I. But the fighting here was intensified by racial hatred, with cries on both sides of “No quarter!”

In a final horror, the battle ended with the massacre of wounded or surrendering Black troops by the Rebels–and by some

of their White comrades in arms. The great attack ended in bloody failure, and the war would be prolonged for another year.

With gripping and unforgettable depictions of battle and detailed character portraits of soldiers and statesmen, No Quarter

compellingly re-creates in human scale an event epic in scope and mind-boggling in its cost of life. In using the Battle

of the Crater as a lens through which to focus the political and social ramifications of the Civil War–particularly

the racial tensions on both sides of the struggle–Richard Slotkin brings to readers a fresh perspective on perhaps the

most consequential period in American history. About the Author: Richard Slotkin is widely regarded as one of the preeminent

cultural critics of our times. A two-time finalist for the National Book Award, he is the author of Lost Battalions, a New

York Times Notable Book, and an award-winning trilogy on the myth of the frontier in America–Regeneration Through Violence,

The Fatal Environment, and Gunfighter Nation–as well as three historical novels: The Crater: A Novel, The Return of

Henry Starr, and Abe: A Novel of the Young Lincoln. He is the Olin Professor of English and American Studies at Wesleyan University

and lives in Middletown,

Connecticut.

Recommended

Reading:

The Final Battles of the Petersburg

Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion (Hardcover). Description: Six large-scale battles from

late March through April 2, 1865, were the culmination of more than nine months of bitter and continuous warfare between Robert

E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant. The fighting climaxed in the decisive breakthrough by the Union Sixth Corps on April 2, just

six miles southwest of Petersburg. This Federal victory forced

Lee to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond

that night, and to surrender his army just one week later. An excellent study on the final union thrusts at Lee's defenses

at Petersburg that culminate not just with Sheridan and Warren's combined collapse of Pickett at Five Forks but the final

break through with the VI corps punching a hole in A. P. Hill's defenses that virtually cause a hemorrhage in the Petersburg

defenses only staved off by the heroic defenses at Fort Gregg and a line of artillery giving time for Lee to organize the

final retreat. Continued below.

Petersburg was a very complicated campaign that contains a series of modest

to large battles as Grant constantly moves forces west to cut off supplies and avenues of escape. As Greene describes well,

Lee constantly parried with creative engineering and counter attacks. Greene provides a detailed account of all these battles

that stretched over one time farms and wilderness outside of Petersburg.

Petersburg was a very complicated campaign and just driving the roads today around Petersburg to some of these still remote sites makes you appreciate

the effort of Greene's work. The final break through is at the center of Pamplin

Historical Park for the Civil

War Soldier where Greene is the Chief historian and CFO. Read the book then visit Pamplin Park, and see the extraordinary

well preserved trenches where the final break through occurred and walk the trail that leads to the Union jump off point and

then follow it right into the Confederate trenches where it leads right to the unique vulnerable spot of the line where the

union attack punched through. It is well worth seeing park with its living history, historic headquarters, outdoor exhibits

and a great modern museum. An excellent book for the serious Civil War student. Included: 25 original maps 36 photos and illustrations

6 x 9; Introduction by award-winning Petersburg historian

Richard J. Sommers; Based on manuscript sources and extensive research. About the Author: Will Greene, executive director

of Pamplin Historical Park, which preserves the Breakthrough Battlefield, places these long-neglected battles in strategic

context while providing the first tactically-detailed account of the combat on April 2, 1865. A. Wilson Greene is also the

author of Whatever You Resolve to Be, a collection of essays on Stonewall Jackson.

Recommended

Reading:

The Horrid Pit: The Battle of the Crater, the Civil War's Cruelest

Mission (Hardcover). Publishers Weekly:

One of the American Civil War's most horrific events took place on July 30, 1864: the slaughter of thousands of Union troops,

including many African-Americans, in a giant pit outside Petersburg, Va. “The Crater” was created as a result of a poorly planned and executed Union

mission to tunnel under, and then explode, the Confederate lines, thereby opening the gates to a full frontal assault on Petersburg

that, if successful, could have helped decide the war. Instead, after several hundred Confederates perished in the initial

mine explosion, the Union troops entered the crater—later known as The Pit—and were gunned down. Continued

below...

(The scene is re-created in the novel and film Cold Mountain.)

Civil War specialist Axelrod (The War Between the Spies, et al.) offers a concise, readable and creditable recounting of the

Battle of the Crater, which General U.S. Grant famously termed a stupendous failure. When the dust settled, the Union forces,

under the inept leadership of generals Ambrose E. Burnside and George Gordon Meade, suffered more than 4,000 killed, wounded

or captured. The well-led Confederates had about 1,500 casualties. The massive slaughter does not make for easy reading, but

is a reminder of the horror of war at its basest level.

Recommended Reading: Battle of the Crater: A Complete History

(Hardcover). Description: One sentence describes this massive study: "It is exhaustive, thorough, detailed, and complete...it

is the most comprehensive study of the crater, the mine." Continued below.

The

Battle

of the Crater is one of the lesser known yet most interesting battles of the Civil War. This book, detailing the onset of

brutal trench warfare at Petersburg, Virginia,

digs deeply into the military and political background of the battle. Beginning by tracing the rival armies through the bitter

conflicts of the Overland Campaign and culminating with the siege of Petersburg

and the battle intended to lift that siege, this book offers a candid look at the perception of the campaign by both sides.

Recommended Reading:

The Crater: Petersburg. Description:

A spectacular early morning underground explosion followed by bloody hand-to-hand combat and unprecedented command malfeasance

makes the story of the Crater one of the most riveting in Civil War history. Da Capo's new "Battleground America" series offers a unique approach to the battles and battlefields of America. Each book in the series highlights a small American

battlefield-sometimes a small portion of a much larger battlefield-and tells the story of the brave soldiers who fought there.

Using soldiers' memoirs, letters and diaries, as well as contemporary illustrations, the human ordeal of battle comes to life

on the page. Continued below…

All of the units, important individuals,

and actions of each engagement on the battlefield are described in a clear and concise narrative. Detailed maps complement

the text and illustrate small unit action at each stage of the battle. Then-and-now photographs tie the dramatic events of

the past to the modern battlefield site and highlight the importance of terrain in battle. The present-day historical site

of the battle is described in detail with suggestions for touring. About the Author: John Cannan has established a reputation

among civil War writers in remarkably short time. His distinctions include three books selected by the Military Book Club.

He is the author of The Atlanta Campaign, The Wilderness Campaign, and The Spotsylvania Campaign. He is an historic preservation

attorney living in Baltimore.

Recommended Reading: The 48th Pennsylvania in the Battle of the Crater:

A Regiment of Coal Miners Who Tunneled Under the Enemy (Hardcover). Description: In June 1864, Grant attempted to seize

the Confederate rail hub of Petersburg, Virginia.

General P.G.T. Beauregard responded by rushing troops to Petersburg

to protect the vital supply lines. A stalemate developed as both armies entrenched around the city. Union commander General

Ambrose Burnside advanced the unusual idea of allowing the 48th Pennsylvania—a regiment

from the mining town of Pottsville—to excavate a mine,

effectively tunneling under Confederate entrenchments. Continued below.

One of the most inventive and creative conflicts of the war, the Battle of the Crater ultimately became one of the most controversial,

as an almost certain Union victory turned into an astonishing Confederate triumph.

Recommended Reading:

Trench Warfare under Grant and Lee: Field Fortifications in the Overland Campaign (Civil War America) (Hardcover) (The University of North Carolina Press) (September

5, 2007). Description: In the study of field fortifications

in the Civil War that began with Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War, Hess turns to the 1864 Overland campaign

to cover battles from the Wilderness to Cold Harbor. Continued below.

With special emphasis on the role

of the 48th Pennsylvania,

this history provides an in-depth examination of the Battle

of the Crater, which took place during July 1864. Here, bickering between Federal commanders and a general breakdown of communications

allowed shattered Confederate troops the opportunity to regroup after a particularly devastating blow to their defenses. The

work examines the ways in which the personality conflict between generals George Meade and Ambrose Burnside ultimately cost

the Union an opportunity to capture Petersburg and bring an

early end to the war. On the other hand, it details the ways in which the cooperation of Confederate commanders helped to

turn this certain defeat into an unexpected Southern achievement. Appendices include a list of forces that took part in the

Battle of the Crater, a table of casualties from the battle

and a list of soldiers decorated for gallantry during the conflict.Drawing on meticulous research in primary sources

and careful examination of trench remnants at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna, Cold Harbor, and Bermuda Hundred,

Hess describes Union and Confederate earthworks and how Grant and Lee used them in this new

era of field entrenchments.

Recommended Reading: Field Armies and Fortifications in the Civil War: The Eastern Campaigns, 1861-1864

(Civil War America) (Hardcover). Description: The eastern campaigns of the Civil War involved the widespread

use of field fortifications, from Big Bethel and the Peninsula to Chancellorsville, Gettysburg,

Charleston, and Mine Run. While many of these fortifications

were meant to last only as long as the battle, Earl J. Hess argues that their history is deeply significant. The Civil War

saw more use of fieldworks than did any previous conflict in Western history. Hess studies the use of fortifications by tracing

the campaigns of the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia from April 1861

to April 1864. Continued below...

He considers

the role of field fortifications in the defense of cities, river crossings, and railroads and in numerous battles. Blending

technical aspects of construction with operational history, Hess demonstrates the crucial role these earthworks played in

the success or failure of field armies. He also argues that the development of trench warfare in 1864 resulted from the shock

of battle and the continued presence of the enemy within striking distance, not simply from the use of the rifle-musket, as

historians have previously asserted.Based on fieldwork

at 300 battle sites and extensive research in official reports, letters, diaries, and archaeological studies, this book should

become an indispensable reference for Civil War historians.

Try the Search Engine for Related Studies: Battle

of the Crater, Petersburg Map, The Mine, Richmond - Petersburg Siege Civil War History, Battle of Petersburg, Union Confederate

Trench Warfare History, Battlefield Maps, Photo, Photos, Details.

Sources: Petersburg National Battlefield

Park; Civil War Preservation Trust; Battles and Leaders of the Civil

War; National Archives; Library of Congress; National Park Service.

|