|

Introduction

With nearly 750 of its 1,000-strong regiment captured in the first two years of Civil War, the remnant could have found

themselves dispirited and drinking from the poisoned well of desertion, and with its final chapter written, each soldier

merely fading into the ages. But this is a story about a regiment that suffered 75% casualties in nearly two

years with 44% becoming fatalities as they withered away in a putrid prison in the North. Regiments are

generally remembered for battlefield feats such as the valiant charge breaching the parapet, dislodging the stubborn foe,

and lifting the enemy's standard while shouting the rebel yell. The 62nd is scarcely remembered because of its atrocious

losses from diseases in a Northern prisoner-of-war camp, but rather for one event that demanded a response just three

days before Lee surrendered to Grant during the closing scene of the conflict. Having evaded capture in the Cumberland Gap

when Confederate forces capitulated on September 9, 1863, the remnant of the 62nd would pursue and clash with bushwhackers

and raiders before being assigned to Palmer's Brigade at Asheville on March 10, 1865. Far from Thermopylae and

lacking a single Spartan, the tested 175 remaining Tar Heels of the 62nd, of their own free will, now formed the nucleus

of 300 men who would make one last stand. Joined by senior and junior reserves, some soldiers at home on leave, convalescent

troops recovering at Asheville, and an artillery battery consisting of two Napoleons, the scant yet determined force would

march into battle to defend Asheville in early April, 1865, from an approaching Union brigade consisting of 1,100

battle-hardened veterans.

| Clark's Regiments |

|

| R.G.A. Love |

History

The 62nd North Carolina Infantry Regiment was formed in the mountain community of Waynesville, North

Carolina, on July 11, 1862, and was composed almost entirely of men from Western North Carolina. Its members were recruited in the counties of Jackson, Haywood, Clay, Macon,

Rutherford, Henderson, and Transylvania. The field officers were colonels George W. Clayton and Robert G. A. Love, and Lieutenant Colonel Byron Gibbs McDowell (often misspelled Bryan),

and they were all descendants of Revolutionary War soldiers.

Colonel Robert Gustavus Adolphus Love, known

by many as R.G.A. Love, initially served as a captain in the 16th North Carolina Infantry in the Army of Northern Virginia. When Captain Love received his

promotion to colonel he transferred to the 62nd North Carolina. The city

of Waynesville, where the unit had formed, was founded by Robert Love, an ancestor of Robert G. A. Love. Major (later lieutenant colonel) Byron Gibbs McDowell was a native of Macon County, and in early 1861 he enlisted in the 39th North Carolina under the command of Col. David Coleman before

being transferred to the 62nd by promotion to Major of the Regiment on July 11, 1862.

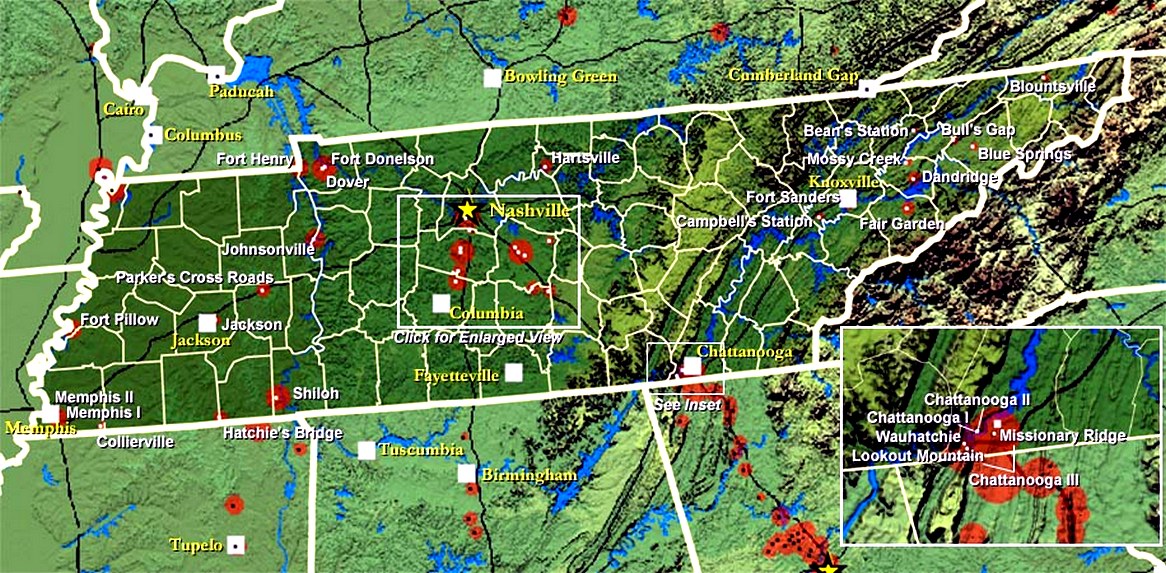

| High Resolution Tennessee Civil War Map |

|

| 62nd North Carolina spent most of the Civil War fighting in East Tennessee |

| Library of Congress |

|

| Prisoners of War at Camp Douglas, 1863 |

This

regiment would spend much of the conflict providing a necessary yet thankless defense of

the region's vital and strategic railroads, and their associated bridges and depots, as well as the prized Saltworks located in neighboring southwestern Virginia. The

unit initially served and fought in East Tennessee, but after two consecutive surrenders of 295 and 442 soldiers respectively,

the remnant of the organization, numbering merely 175 men, would reform in Asheville, North Carolina, and serve there

for the remainder of the war.

In late December 1862, while guarding bridges and railroads in East

Tennessee, three poorly armed companies

(295 soldiers) of the 62nd North Carolina were overrun and captured by a well-equipped Union cavalry force of 3,000. In

July 1863 the regiment was attached to General Gracie's Brigade and stationed in the Cumberland Gap. In a concerted effort,

the 58th, 62nd, 64th, and 69th (Thomas' Legion) North Carolina regiments fought the enemy in East Tennessee and across the border in western North Carolina.

General Ulysses S. Grant,

while traveling through the Cumberland Gap in 1864, noted that "with two brigades of the Army of the Cumberland I could

hold that pass against the army which Napoleon led to Moscow."

Major McDowell, 62nd North Carolina, when referring to the Cumberland Gap in early September 1863, stated:

"When I was told by General Frazer that I had been surrendered, and that I and my regiment were prisoners of war my indignation

and that of my regiment knew no bounds. I informed him that I would not be made a prisoner of war that it took two to make

such a bargain as that under the circumstances, and that he could not force me to do so. Sharp words were exchanged, and I

called up all of the Sixty-second Regiment who were willing to take their lives in their hands and all of the other commands

in the Gap who were willing to join us, and said to them, 'If you will go with me we will go out from here, and let consequences

take care of themselves.'"

Although Confederate General John Wesley Frazer would, without offering any resistance to the foe, surrender the regiment in the Cumberland Gap on September 9, 1863, an estimated 600 from various

units evaded capture after refusing to obey Frazer's capitulation order. After the uncontested fall of the Gap, the 62nd

North Carolina would return to the Asheville area and in April 1864 it recorded 178 men. The records further indicate that

a staggering 442 men of the 62nd were surrendered by Frazer and held as prisoners at Camp Douglas. And in O.R., 1, 30, 11, pp. 636-637,* Major

McDowell discusses the Cumberland Gap's surrender, with President Jefferson Davis endorsing

the report by stating that Frazier's surrender "presents a shameful abandonment of duty." *Official Records of the

Union and Confederate Armies; hereinafter cited as O.R.

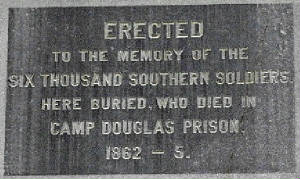

| Camp Douglas Prison |

|

| Confederate Memorial |

The 442 prisoners were transferred to Camp

Douglas, Illinois, but some of the soldiers were relocated to prisoner

of war camps Rock

Island, Illinois, and Camp Morton, Indiana. When the Cumberland Gap capitulated, 24 officers of the 62nd, nearly all

of its leadership, were captured. The officers, however, were segregated and imprisoned at Point Lookout, Maryland, and Johnson's Island, Ohio. For many of the

these unfortunate Tar Heels, forty-four percent, Camp Douglas would be a one way trip with the final destination

called the grave. The majority of these men in reality were boys, 18 perhaps 19, and many had never ventured beyond the local

county line. Now, like flowers trampled under the clamoring hoofs of advancing horsemen, these young men had just fallen

victim to a rich man's war. They would never hear the soft voice of a bride, nor would they ever enjoy the blessings

of fatherhood, but back home many moms and dads would be on the receiving end of a piercing message telling them that their

son, a pow, had died and been buried in a mass grave on Yankee soil known as "The Confederate Mound." The regiment's death toll at Camp Morton, Rock Island, Point Lookout and Johnson's

Island remains unknown. Remove the notion of a 90-day war and prisoner exchange, because this was now what many

called hard war. (See

also American Civil War Prisoner of War Camps.)

Major

McDowell was the only 62nd field officer present during the surrender of the Cumberland Gap. During the capitulation, Colonel Love was ill and not present (North Carolina Standard, October 7, 1863), and Lt. Col. Clayton had contracted typhoid fever and was in a hospital

in nearby Greeneville, TN. In

Jan. 1865, according to O.R., Series 3, Volume 4, p. 1037, and just three months prior to Lee surrendering to Grant, imprisoned 62nd North

Carolina men were offered pardons if they joined the Union Army. Although most of the imprisoned men of this unit had

already succumbed to an agonizing death at Morton, known as the Andersonville of the North, McDowell wrote that

not one soldier from the 62nd accepted the offer.

The 62nd,

now greatly reduced in numbers, would continue trekking the rugged terrain while fighting and scrapping with a

variety of determined opponents, from outlaws, deserters, bushwhackers, outliers, to escaped Union prisoners. Fighting against bushwhackers

and guerrillas had now replaced the standing army in the field, but most men, if given the choice, still preferred fighting

in pitched battles using Napoleonic Tactics. Bushwhackers were by definition masters of the ambush, but they

were considered by the masses as murderers because they refused to engage in civilized warfare, meaning a gentlemen's

fight. The guerrillas, however, were only striving to even the odds with their hit and run tactics against a much larger

and better armed force. War is war, kill or be killed, so like a clap of thunder out of a clear sky they attacked and like

a ghost in the night they vanished.

In early 1864 Captain B. T. Morris of the 64th North Carolina (known as Allen's Regiment) recorded that while fighting bushwhackers,

McDowell had been shot through the arm. (The 64th would forever be associated with the Shelton Laurel Massacre.) The 62nd continued the fight under generals Breckinridge (14th Vice President of the United States and cousin to Mary Todd Lincoln), Vaughn, and Williams in East Tennessee. Whereas in March 1865 the regiment was

attached to Colonel J. B. Palmer's brigade at Asheville, the unit soon disbanded near the French Broad River.

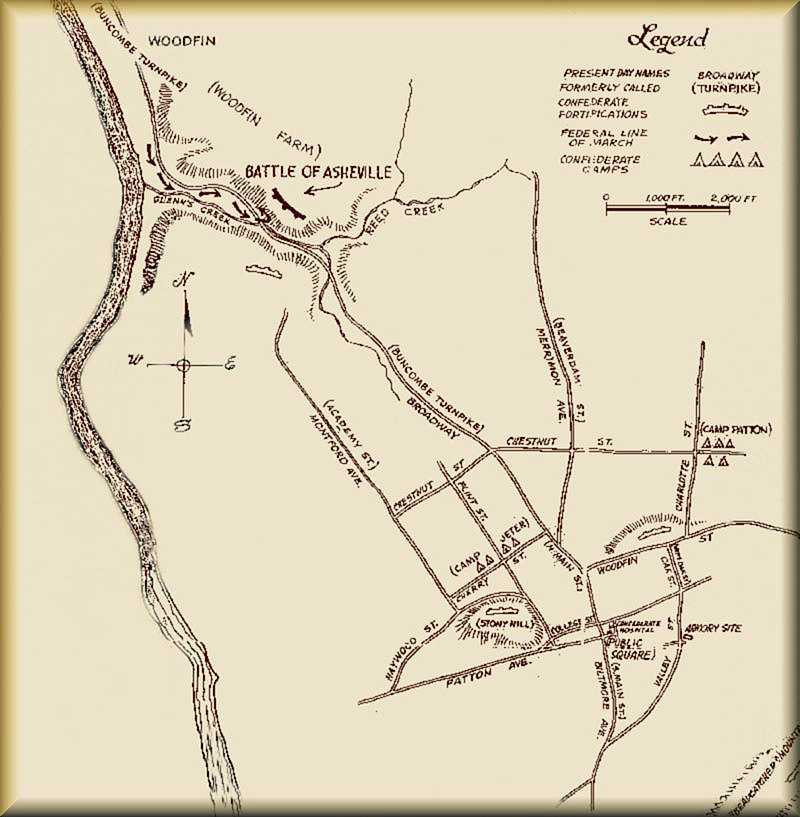

| Map of Civil War Battle of Asheville, NC |

|

| High Resolution Map of Battle of Asheville, North Carolina |

The 62nd

North Carolina was one of the state's last regiments to surrender during the war. With the fragment of the regiment forming

part of Palmer's brigade at Asheville on March 10, 1865, and at the direction of General Martin, it engaged and thwarted Kirby's brigade near Asheville on April 6.

Prior

to disbanding this regiment, Col. George Clayton gathered the scant force of 300 Confederates and two small brass Napoleon

cannons and marched them to rough earthworks on a hill that overlooked the French Broad route being used by the advancing 1,100

soldiers under the command of Ohioan Col. Isaac Kirby. When the two forces engaged at 3 o’clock in the afternoon,

they held their positions and began firing. There was no maneuvering, but gunfire, with sporadic cannonading,

which continued for five hours.

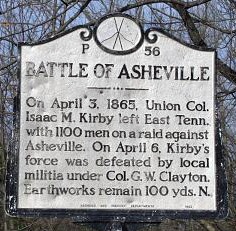

| Historical Marker |

|

| Civil War Battle of Asheville, NC |

On April 3, 1865, Colonel Kirby, formerly commanding the 101st Ohio Infantry, was ordered to advance

his 1,100 strong brigade, with ten days' rations, from East Tennessee and capture Asheville, if he could do so without suffering high casualties, and he was assisted by Confederate deserters familiar with the terrain. Kirby advanced his force

into the Tar Heel state and camped at Warm Springs, a city adjacent the Tennessee line, and followed the French Broad River with his brigade of 900 infantrymen and an estimated 200 partisans, including rebel deserters who had pledged an oath of allegiance to the United States,

two cannon, and a train of wagons. Kirby, leaving his field pieces and wagons at Warms Springs, cautiously approached

Asheville on April 6 and, bar significant resistance, planned to sack the pristine mountain city, but Col. Clayton, a native of North Carolina who had also attended West Point, with a mixed force of 300 Confederates, including 175 of the faithful 62nd North Carolina, were determined to

make a stand. To the west, 600 men of Thomas' Legion of Cherokee Indians and Mountaineers, a diverse unit of the rugged region, were stationed between Waynesville and Warm Springs (O.R., 49, 1, 31) and poised to engage any Yankee incursion in that vicinity. Clayton was assisted by a company of the Silver Greys and some Confederate soldiers at home on sick leave and furlough. The Silver Greys,

consisting of senior and junior reserves, served as home guard and totaled 44 men, including a 14 year old boy and a 60 year old Baptist minister.

| Battle of Asheville & Vicinity Map |

|

| Map of Battle of Asheville |

| Battle of Asheville |

|

| Civil War History |

(Right) View of the Asheville

battlefield. Confederate artillery was placed on the hills across the road. The battle's historical marker is also in center

background.

McConnell's brigade, meanwhile, was

en route to support Kirby, who had opined that Confederate infantry of 1,000 to 1,500 with an additional 1,100 cavalry

confronted him. So in a calculated move, Kirby ordered his men forward without the supporting brigade. At approximately 3 p.m., while the Federal brigade

deployed, the rebels commanded positions on the ridge, causing the Federals to hastily confront them at short range

(the location is currently known as Broadway Street). The battle commenced

and the armies, with neither striving to gain the advantage, remained static and exchanged volleys until 8 o'clock that night. Although greatly outnumbering its foe, the Union army preferred to

retreat, and the opposing forces reported but few casualties.

Kirby's

actions showed that he lacked conviction to press an assault on Asheville, not to mention capturing it, because he left

his field pieces and wagons, having been filled with ten days' rations, some 30 miles to the north at Warm Springs,

which allowed the Ohioan a quick exit should those imaginary 1,100 cavalry thrash his position. Absent was any maneuvering

of his brigade, for he had ample time, five hours, to ascertain the position and strength of the enemy, which he later

conceded was merely a small force of rebels with two cannons that entertained him from two positions on a hill.

Whereas Kirby refused any flanking movement, he did perform a token demonstration before the Confederates, who had used

the topography to its advantage. Perhaps he was hoping that the Confederates would exhaust their ammunition, or melt away

like fluke flurries in the springtime, and then move toward the city in piecemeal fashion. But with the curtain closing

on the final scene of this war, Kirby, by not pressing the Rebels, had also avoided additional unnecessary losses for both

armies.

And three days later,

after General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, the Confederates serving

with Clayton in Asheville withdrew and returned to their homes, and they never swore the oath of allegiance as required

by Federal authorities. Perhaps receiving some solace after four years of fighting, with the war having erased many

of their comrades from their Southern communities, several veterans from the unit later commented that we didn't

surrender, we just quit. Lt. Col. McDowell wrote that "No braver or nobler hearted men ever lived than those composing the

Sixty-second North Carolina Infantry Regiment."

Although

Asheville had averted capitulation, it was soon captured, April 26, 1865, during Stoneman's Cavalry Raid. The city's fall, however, occurred almost two weeks after Lee's surrender to Grant at Appomattox on April

9, but coincided with Gen. Joe Johnston's surrender to Gen. William Sherman at Bentonville, North Carolina. (See Official Order of Surrendering Confederate Forces.)

(Sources and related reading listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended Reading: To Die in Chicago: Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas 1862-65

(Hardcover) (446 pages). Description:

The author’s research is exacting, methodical, and painstaking. He brought zero bias to the enterprise and the

result is a stunning achievement that is both scholarly and readable. Douglas, the "accidental" prison camp, began as a training

camp for Illinois volunteers. Donalson and Island #10 changed that.

The long war that no one expected… combined with inclement weather – freezing temperatures - primitive medical

care and the barbarity of the captors created in the author’s own words "a death camp." Stanton's and Grant's policy

of halting the prisoner exchange behind the pretense of Fort

Pillow accelerated the suffering. Continued below...

In the latest

edition, Levy found the long lost hospital records at the National Archives which prove conclusively that casualties were

deliberately “under reported.” Prisoners were tortured, brutality was tolerated and corruption was widespread.

The handling of the dead rivals stories of Nazi Germany. The largest mass grave in the Western Hemisphere is filled with....the

bodies of Camp Douglas dead, 4200 known and 1800 unknown.

No one should be allowed to speak of Andersonville until they have absorbed the horror of Douglas, also known as “To

Die in Chicago.”

Related Reading:

Additional Reading:

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in North Carolina.

Description: Numerous battles and skirmishes were fought in North Carolina during the Civil War, and the campaigns and battles themselves were crucial

in the grand strategy of the conflict and involved some of the most famous generals of the war. Continued below...

John

Barrett presents the complete story of military engagements across the state, including the classical pitched battle of Bentonville--involving

Generals Joe Johnston and William Sherman--the siege of Fort Fisher,

the amphibious campaigns on the coast, and cavalry sweeps such as General George Stoneman's

Raid. Also available in hardcover: The Civil War in North Carolina . .

Recommended Reading: East Tennessee and the Civil War (Hardcover) (588 pages). Description: A solid social, political, and military history, this work gives

light to the rise of the pro-Union and pro-Confederacy factions. It explores the political developments and recounts in fine

detail the military maneuvering and conflicts that occurred. Beginning with a history of the state's first settlers, the author

lays a strong foundation for understanding the values and beliefs of East Tennesseans. He

examines the rise of abolition and secession, and then advances into the Civil War. Continued below...

Early

in the conflict, Union sympathizers burned a number of railroad bridges, resulting in occupation by Confederate troops and

abuses upon the Unionists and their families. The author also documents in detail the ‘siege and relief’ of Knoxville.

Although authored by a Unionist, the work is objective in nature and fair in its treatment of the South and the Confederate

cause, and, complete with a comprehensive index, this work should be in every Civil War library.

Recommended Reading: Confederate Military History Of North Carolina: North Carolina In The Civil War, 1861-1865. Description: The author,

Prof. D. H. Hill, Jr., was the son of Lieutenant General Daniel Harvey Hill (North

Carolina produced only two lieutenant generals and it was the second highest rank in the army) and

his mother was the sister to General “Stonewall” Jackson’s wife. In Confederate

Military History Of North Carolina, Hill discusses North Carolina’s massive

task of preparing and mobilizing for the conflict; the many regiments and battalions recruited from the Old North State;

as well as the state's numerous contributions during the war. Continued below...

During Hill's

Tar

Heel State study, the reader begins with

interesting and thought-provoking statistical data regarding the 125,000 "Old

North State" soldiers that fought

during the course of the war and the 40,000 that perished. Hill advances with the Tar Heels to the first battle at Bethel, through numerous bloody campaigns and battles--including North Carolina’s

contributions at the "High Watermark" at Gettysburg--and concludes with Lee's surrender at

Appomattox.

Recommended Viewing: The Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns. Review: The

Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns is the most successful public-television miniseries in American history. The 11-hour Civil War didn't just captivate a nation,

reteaching to us our history in narrative terms; it actually also invented a new film language taken from its creator. When

people describe documentaries using the "Ken Burns approach," its style is understood: voice-over narrators reading letters

and documents dramatically and stating the writer's name at their conclusion, fresh live footage of places juxtaposed with

still images (photographs, paintings, maps, prints), anecdotal interviews, and romantic musical scores taken from the era

he depicts. Continued below...

The Civil War uses all of these devices to evoke atmosphere and resurrect an event that many knew

only from stale history books. While Burns is a historian, a researcher, and a documentarian, he's above all a gifted storyteller,

and it's his narrative powers that give this chronicle its beauty, overwhelming emotion, and devastating horror. Using the

words of old letters, eloquently read by a variety of celebrities, the stories of historians like Shelby Foote and rare, stained

photos, Burns allows us not only to relearn and finally understand our history, but also to feel and experience it. "Hailed

as a film masterpiece and landmark in historical storytelling." "[S]hould be a requirement for every

student."

Recommended Reading: Mountain Rebels:

East Tennessee Confederates and the Civil War, 1860-1870 (240 pages) (University

of Tennessee Press). Description:

In this fine study, Groce points out that the Confederates in East Tennessee suffered more for the ‘Southern Cause’

than did most other southerners. From the first rumblings of secession to the redemption of Tennessee

in 1870, Groce introduces his readers to numerous men and women from this region who gave their all for Southern

Independence. Continued below...

He also points out that East Tennesseans were divided in their loyalties and that slavery played only a small role. Groce goes

to great lengths to expose the vile treatment of the Region’s defeated Confederates during the Reconstruction. Numerous

maps, pictures, and tables underscore the research.

Sources: Official Records of

the Union and Confederate Armies (OR), O.R., Series IV, pt. 2, pp. 732-734, O.R.,

Series 1, Volume 53, pp. 324-336, and O.R., Series 1, Vol. 32, pt. II, pp. 610-611; National Archives

(NARA); Library of Congress (LOC); National Park Service: American Civil War (NPS); State Library of North Carolina;

North Carolina Office of Archives and History; North Carolina Museum of History; Walter Clark's Regiments: Histories

of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-65; Weymouth T. Jordan and Louis H. Manarin, North Carolina Troops, 1861-1865; Joseph H. Crute, Jr., Units of the

Confederate States Army; D. H. Hill, Confederate Military History Of North Carolina: North Carolina In The Civil War, 1861-1865; Forster A. Sondley, A History of Buncombe

County (North Carolina), 2 vols. (1930).

|