|

By B. G. McDOWELL,

LIEUTENANT-COLONEL

The Sixty-second Regiment was composed almost entirely of Western North

Carolinians, officers and men.

The companies composing the same met at Waynesville July 11, '62, and organized

by electing the following:

R. G. A. LOVE, Colonel, Waynesville, N.C.

G. W. CLAYTON, Lieutenant-Colonel,

Asheville, N.C.

B. G. MCDOWELL, Major, Macon county, N.C.

| Colonel RGA Love |

|

| (Clark's Regiments) |

STAFF AND COMPANY OFFICERS.

The staff and company officers were as follows:

R. B. JOHNSON, Captain

and Quartermaster, of Asheville.

PATRICK THRASH, Captain and Commissary of Subsistence, Buncombe county.

DR.

H. M. ROGERS, Surgeon, Haywood county.

DR. G. P. S. ALLEN, Assistant Surgeon, Haywood County

LIEUTENANT JAMES H. MCALISTER,

Assistant Commissary of Subsistence

JOSEPH F. HAYNES, Adjutant, of Knoxville, Tennessee

The commanding officers of all these companies were, as elected:

COMPANY A-Haywood County-A. T. Rogers, Captain; W. H. Leatherwood, First

Lieutenant; F. R. Furgerson and Geo. H. Nelson, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY B-Clay County-Captain, Benjamin Moore; C. M.

Crawford, First Lieutenant; J. J. McClure and M. Passmore, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY C-Haywood County-Captain, John Turpin;

J M. Tate, First Lieutenant; Jere Ratcliff and Robert L. Owen, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY D-Macon County-Captain, R. M.

Henry; M. L. Kelly, First Lieutenant; L. Enloe and W. P. Norton, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY E- Haywood County-Captain,

B. A. Edmondson and J. Ramsey Dills; W. H. Bryson, First Lieutenant; B. M. Wilson and M. L. Allison, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY

F-Rutherford County-Captain, A. B. Cowan; Jas. M. Taylor, First Lieutenant; Jno. Jones and D. D. Walker, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY

G~Jackson County-Captain, A. D. Hooper; D. F. Brown, First Lieutenant; B. N. Queen and P. M. Parker, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY

H-Henderson County-Captain, W. G. B. Morris; J. M. Owen, First Lieutenant; G. W. Whitmore and I. F. Galloway, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY

J-Haywood County-Captain, William J. Wilson; I. P. Long, First Lieutenant; J. A. Burnett and P. G. Murray, Second Lieutenants.

COMPANY K-Transylvania County--Captain, L. C. Neil; S. C. Beck, First Lieutenant; jas. M. Gash and V. C. Hamilton,

Second Lieutenants.

The Field Officers were happily chosen. Colonel Love was a leading and influential

citizen of Haywood county, a man of first-class ability and often held places of trust, honor and profit, as the gift of his

people, until his health gave way under disease, which resulted in his death after the war. He was Lieutenant-Colonel of the

Sixteenth North Carolina Regiment in the Army of Northern Virginia, and was transferred by promotion to

the Sixty-second.

Lieutenant-Colonel Clayton was of Buncombe county, North Carolina,

and a resident of the city of Asheville, a graduate of West Point,

of a most excellent family, an elegant gentleman, a magnificent disciplinarian, and was loved by every member of his regiment.

Colonel Clayton died recently greatly lamented by a large circle of friends and relatives and mourned by his comrades in arms

who shared with him the privations and hardships of a soldier's life.

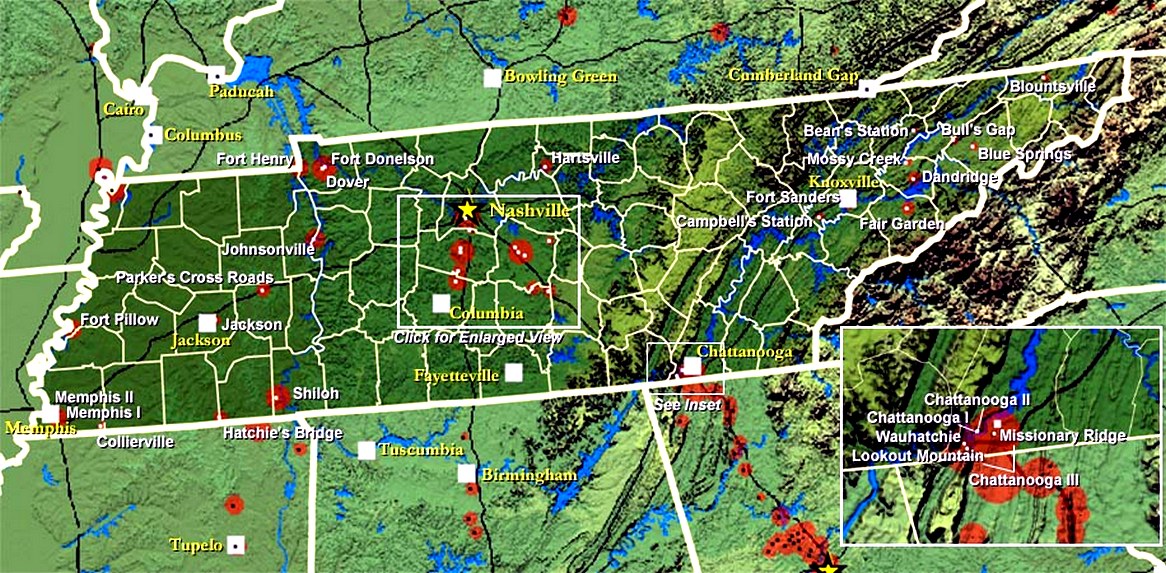

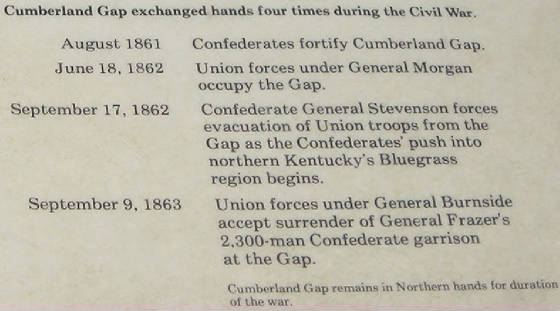

While stationed at Cumberland Gap, a point which figured conspicuously in the late war between the States,

Colonel Clayton fell a victim to typhoid fever. He was removed to a hospital at Greenville,

Tennessee. Very soon after he left, the siege of Cumberland was on, and he could not return to his command at the Gap. Colonel Love was off

on sick leave at the time, so the command of the regiment was left in the hands of the Major of the regiment Lieutenant-Colonel

Clayton was not, therefore, able to return to his regiment until after the surrender of Cumberland Gap (9 September, 1863),

when that portion of the regiment which escaped from the Gap was assembled at Pigeon river, in Haywood county, to be again

prepared to enter into active service.

Major, later Lieutenant-Colonel, B. G. McDowell, was a native of Macon county, N. C. Early in 1861, he enlisted in the 39th North Carolina under Colonel David Coleman and was transferred to the

62nd by promotion to Major of the Regiment 11 July, 1862.

All three of these officers were descendants of revolutionary soldiers,

and appropriately commanded men, most of whom were also lineal descendants of the heroes of 1776 and as brave and patriotic

as their ancestors.

Want of space precludes the possibility of the mention of even the names

of this heroic band which are given, with some omissions and inaccuracies in Moore's

Roster, Vol.8, p. 716, et seq. Their descendants should remember and be proud of the membership of their parents in such a

command.

| 62nd North Carolina suffered heavy casualties here |

|

| Panoramic View of Cumberland Gap |

| High Resolution Map of Tennessee Civil War Battles |

|

| (Map) 62nd North Carolina half the Civil War on East Tennessee Battlefields |

EAST TENNESSEE.

Soon after the organization the regiment started Haynesville (now called Johnson's

City), in Washington county, Tennessee,

arriving there about 1 August, 1862, when it was placed under rigid drill and prepared for active service. A braver or more

courageous body of men did not belong to the Confederate army. They left their homes, a majority of them leaving families

dependent upon them and offered their lives a sacrifice upon the field of battle for a cause they thought to be right. The

rank and file of this regiment were of the very best citizens of Western North Carolina. A finer or braver set of men, taken all together I have never seen. This

regiment when it went into camp for drill, was without arms, except a few old muskets were furnished them for drilling purposes.

The regiment had not been in camp at Haynesville but a few days, when

it was separated, three companies going to Zollicoffer (now Bluff

City). Three to Carter's Depot (now South Watauga), two to Limestone,

in Washington county the rest of the companies remaining at Haynesville (now Johnson's City)-all

these points in Tennessee. The writer of this sketch was

sent to Zollicoffer, to take charge of the three companies there, put them under rigid drill, and at the same time guard the

bridge spanning the Holston river at that point and prevent railroad communication from being

disturbed. The other two companies mentioned were put to like service. A very small amount of ammunition was furnished the

forces placed in camp for drill and guard duties. This was true as to this regiment. We had a few old fashioned muskets, and

a small amount of ammunition furnished for the purposes indicated. In this condition, this regiment was by no means in condition

to meet an attack by the enemy, especially when in any sort of considerable force, being simply in a camp of instruction.

In the early fall of 1862, date not now remembered, one Battalion of

the Regiment under Lieutenant-Colonel Clayton was ordered to Causby Creek, Cocke county, Tennessee, to help suppress an uprising

of disloyal citizens there. It seems that some conscripts and deserters had been turned out of the Waynesville jail by their

friends. Sheriff Noland while pursuing them, was killed on Noland or Utah

Mountain, three miles north-east of town. The militia of the county was

called out and followed the outlaws to the Tennessee line,

via Cattaloochee and Big Creek, north forty miles.

Major W. W. Stringfield with 150 Cherokee Indians and whites of the Sixty-ninth North Carolina, also on a scout in Sevier county, Tenn., and Jackson county, N. C., rapidly

crossed the Balsam mountains at Soco Gap (fifteen miles northwest of Waynesville) and in company with several hundred militia-old

men and boys under Major Rhea and Colonel Rogers, Green Garrett, Arch Herren and others crossed over the Tennessee line, killed

several of the outlaws and soon reduced the others to submission.

The Sixty-second, badly armed and equipped as it was, presented a formidable

and war-like appearance. The outlaws were killed, captured or scattered and restive citizens were quieted. Not a great while

after this the Sixty-second was ordered to Greenville, Tenn.,

the home of President Johnson. It was there brigaded with the Sixty-ninth North

Carolina and others and all were subjected to drill and discipline. Railroad bridges were now threatened

both from external as well as internal forces. The raid of General Carter mentioned above and its success emboldened all the

peop1e three-fourths of whom were "followers of Belial" and disloyal to the South. All the bridges and depots were threatened

and some were burned. Hayden and others were hung and hundreds sent South to prison and thousands ran off North and joined

the Union army.

I have noticed, in Brigadier-General Frazer's report, of his disgraceful

surrender of Cumberland Gap, he refers to this regiment as at one time having been commanded by its Major (referring of course

to the writer), and as having been surrendered by him to a gang of Yankee scouts, or raiders. A more unblushing falsehood

was never penned by living man.

CAPTUPE

OF THREE COMPANIES.

I have stated the condition of the three companies under my immediate

command at Zollicoffer, which eliminates necessity of repeating it here. On the night of 30 December 1862, General Samuel

P. Carter, with three regiments of Federal cavalry, made his (the first) raid into East Tennessee

for the purpose of burning the bridges and destroying railroad communication. The East Tennessee

& Virginia Railroad bridge at Zollicoffer was the first point struck by this "Yankee raid," of not less than 2,500 men.

I was there with three companies of poorly armed men, with no means of defense and absolutely helpless. In this condition

these three companies were surrendered. And yet, the gallant Frazer has me surrendering this whole regiment to a Yankee scouting

party. His false and slanderous statement is found on page 611, Official Records Union

and Confederate Armies, Vol. 51.

The men were paroled, and as soon as exchanged, which was but a short

time, they were ordered to Cumberland Gap, and composed a part of the garrison of the Gap.

In February, 1863, the balance of the regiment was stationed at Greenville, Tenn.,

and in March and April were in General A. E. Jackson's Brigade

at Strawberry Plains. At the end of July the regiment was in Gracie's Brigade at Cumberland Gap.

General Gracie was in command at the Gap when the regiment reached that

point, but did not remain but a short time, being ordered away, and was succeeded by General Frazer.

SURRENDER

OF CUMBERLAND GAP

General John W. Frazer was in command at Cumberland

Gap when the surrender of that stronghold occurred 9 September, 1863. The force we had at the Gap, was, of course,

insignificant when compared with the Federal forces which approached the Gap on both sides, when the siege began, but the

surrender of the Confederate forces there was a shame and disgrace, when the situation is fully understood. The approaches

to the Gap were of such character that it would have been impossible for any number of men to have captured the post by force.

The opportunity of General Frazer to have evacuated the Gap and saved his command from a long imprisonment and death (as was

the ease with many of them) was open, and nothing but treachery, or cowardice, or it may be both, could have led to the unconditional

surrender of this, the strongest natural position in the Confederate States, and with it, 2,026 prisoners, 12 pieces of artillery,

and the stores of ammunition and provision.

| Union army assumes control of Cumberland Gap |

|

| Gen. Burnside and Union invasion of Cumberland Gap in Sept. 1863, Harper's Weekly, Oct. 1863 |

| Cumberland Gap Civil War Battles |

|

| 62nd North Carolina Fight for their Lives while in the Cumberland Gap |

| Cumberland Gap Civil War History |

|

| Why was the Cumberland Gap important during the Civil War? |

The writer has read, over and over again, the report of the surrender

of Cumberland Gap,

as given by General Frazer, and wondered if an opportunity would ever be offered for the vindication of our men at the Gap,

from the miserable slanders hurled against them by Frazer in his attempt to shield himself from public censure. The report

of this surrender made by him in Volume 51, pages 604, et seq) is to my own personal knowledge false in every essential particular,

and does the brave men who composed the garrison at the Gap the greatest wrong. It should be corrected and handed down in

history, just as it occurred, and let the blame rest where it rightfully belongs. I think we have reached the point that when

known facts are given to the public for consideration and approval, or rejection, public sentiment will invariably reach a

just conclusion.

It would, even at this late day, be exceedingly difficult for General

Frazer to convince the survivors of the Cumberland Gap disaster, that he did not surrender

for a money consideration.

This regiment when it reached the Gap, had about 800 men for duty. There

were a few deserters from this regiment, but not more than was common from nearly all regiments. Desertions were by men who

returned to their homes. They did not go to the enemy.

Shortly after we reached the Gap, Colonel Love left the regiment on

account of extreme bad health, from which he never recovered, but ultimately died as has been stated. It was not long thereafter

until Lieutenant-Colonel Clayton was taken sick of typhoid fever, and was removed to the hospital at Greenville, Tenn., and was away from the Gap when the siege

began, and when the command was surrendered. The siege of Cumberland Gap began 7 September,

1863. General DeCourcy commanded the Federal forces on the Kentucky side and General Shackelford

on the south or Tennessee side. It was in reality Burnside's

army on the south side of the Gap. The writer was the only field officer of the Sixty-second Regiment there at the time. I

was placed, with almost my entire regiment, out on the Harlan county road on picket duty. This road overlooked the valley

leading down what was then, and is I think still, known as Yellow creek. Skirmishing and picket firing was continuous out

on road, after the siege began, and not unfrequently the enemy from the Kentucky

side assaulted our position along this road in strong force, and made repeated determined to drive us from our position. It

affords me pleasure now to say, and will be a pleasure to me to know as long as I live, that men never behaved with more coolness

and courage than did the men of the Sixty-second Regiment. Kain's Battery, commanded by Lieutenant O'Connor, was stationed

on what was known as the East Mountain,

only a short distance from where I was on duty with my regiment. We had been advised during the day of the 9th of the repeated

demands that had been made for the surrender of the Gap, and of General Frazer's refusal, and felt entirely confident that

we would not be surrendered, because it was utterly unnecessary owing to the fact that he could take the entire command out

of the Gap at any time, against any odds. The situation was such that he could not have been prevented from doing so; and

he well understood this if he understood anything. It was understood all along the line that the battle would open at noon

on 9 September, 1863. Noon came, but no battle. The writer went up on top of the East

Mountain and found Lieutenant Thomas O'Connor at his battery, from which

point of vantage we had a splendid view of Burnside's army and all that was going on. We both observed that flags of truce

were passing in and out of the Gap rather too frequently to make us feel comfortable, hut we had no information, though we

suspected that something was wrong in some way. Just about sunset that day, a courier come to me from General Frazer with

an order to report at the General's headquarters, with my regiment at once Then I began to realize that our suspicions were

well founded. I returned to the Gap with my men, who had been on duty for nearly a week without intermission or relief, but

not a man had flinched from duty for a moment. There I found General Frazer sitting in front of his tent surrounded by his

staff officers. All the commanding officers of regiments and batteries arrived at General Frazer's headquarters about the

same time. That was absolute]y the only consultation called, and we were then informed by General Fraser that we were surrendered.

Every officer bitterly opposed being surrendered, and some of them denounced it in the most vigorous terms as cowardly and

unwarranted by the conditions surrounding us at the time.

A detachment of sixty men (not one hundred and twenty five as stated

by General Frazer), had been detailed from the various regiments to guard a little mill which rested just at the foot of the

mountain on the south side, and which served to grind meal for the army at the Gap. Immediately in front of this little mill

was Burnside's whole army. The Federal commander sent a force sufficient for the purpose which under cover of heavy artillery

firing, attacked the guard at this mill and dispersed it, the guard being utterly insufficient to meet the emergency. They

could do nothing but fall back on the command in the Gap, or stand and be shot down like brutes, as they would have been,

had they not fallen back on their commands. And yet the gallant General Frazer and his engineer, Rush VanLeer, would have

according to their own statement, 125 men hold this mill against side's whole army, numbering anywhere from 10,000 to 20,000

men.

ESCAPE.

When I was told by General Frazer that I had been surrendered, and that

I and my regiment were prisoners of war my indignation and that of my regiment knew no bounds. I informed him that I would

not be made a prisoner of war that it took two to make such a bargain as that under the circumstances, and that he could not

force me to do so. Sharp words were exchanged, and I called up all of the Sixty-second Regiment who were willing to take their

lives in their hands and all of the other commands in the Gap who were willing to join us, and said to them, "If you will

go with we will go out from here, and let consequences take care of themselves."

In all about 600 responded, and led by Colonel Slemp and a man from

Abingdon, Va., whose name was Page, as I remember, both of whom were perfectly familiar with the country, we moved out of

the Gap, eastward, passing Kain's battery and pushing one rifle piece over the cliff as we went along. We made our way along

the north side of the mountain, on the Kentucky side, until

we reached a point opposite Jonesville, where we encountered a pursuing force of Federal cavalry. Our entire escaping force

had kept their guns and ammunition, expecting a collision as we went out, and being thus prepared, an immediate dash was made

by our men. Having the decided advantage of position, we forced the Federal cavalry to retire and were permitted to pass on,

the Federals returning to the Gap, after burning the little town of Jonesville, in Lee county,

Va. We made our way to Bristol, Tennessee, and Zollicoffer,

and I at once reported the surrender to Major C. S. Stringfellow, Adjutant-General, and awaited further orders from the General

commanding.

CAMP

ON PIGEON RIVER.

After the surrender of Cumberland Gap, the men of the Sixty-second Regiment

who were at home on furlough, and all those who escaped capture went into camp at Pigeon river, in Haywood County, N. C. After remaining there

for a few days, they entered again into active service and never for one moment flinched from any duty assigned them, nor

from constant danger to which they were exposed, to the end of the war. In April, 1864, the fragment of the regiment was at

Asheville under command of Captain Aug. B. Cowan and reported

178 men.

About this time Colonel Love resigned as Colonel of the regiment, and

Lieutenant-Colonel Clayton was raised to the rank of Colonel, and the writer to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and Captain

Rogers, of Company A, to the rank of Major.

This regiment (and by this I mean that portion which escaped capture)

engaged in all the East Tennessee campaigns under General Breckinridge, General Vaughn and General Williams. The men of this

regiment were the very last men to lay down their arms and very many of them never did take the oath of allegiance, which

was required as every one knows, of all Confederate soldiers at the close of the war.

Immediately after the surrender of Cumberland Gap,

General Frazer and the men who did not escape from the Gap, were removed to Federal prisons, where those who did not die from

disease remained until the close of the war. On 30 December, 1863, there were 443 of the Sixty-second in person at Camp Douglas, 119 Official Records Union

and Confederate Armies, p. 797. What became of General Frazer the writer does not know. After the surrender of the Gap, so

far as I am advised, he was never heard of again beyond his lying report above cited, which purports to have been written

at Fort Warren, in Boston harbor, November, l864.

General Frazer in his report of the surrender of the Gap, reflects severely

and most unjustifiably upon the character of the troops and morale of the command. I was at my post of duty from the day the

regiment arrived at the Gap till the surrender, and knew as much of the morale and character of the command as General Frazer,

or any one else, and do most positively deny his charges.

On page 611, Vol.51, Official Records Union and Confederate Armies,

he says: "The Colonel was absent and soon after resigned and became an open advocate of reunion in county." This, of course,

refers to Colonel Love, who later on resign on account of extreme bad health, from which he died, as stated herein. But the

allegation of his entertaining Union sentiments as published by General Frazer, who was then in prison and who never saw or

heard of Colonel Love after the surrender of Cumberland Gap, is unfounded in fact. It is

due to the memory of Colonel Love, who was loyal to the cause of the south, to the very end, and even after all hope was lost,

to denounce this statement as abso1utely untrue.

There are now numerous living witnesses to attest the truth of the foregoing.

It is astonishing to think how docile, loyal and obedient were the men to their superior officers. It was such a surprise

however, that no one had to think, ere we were in the hands of our enemies.

General Frazer was bitterly denounced by his brother officers after

going to prison, and we are told by good men like Lieutenant J. M. Tate, Lieutenant R. A. Owen, W. H. Leatherwood of Haywood

county, and others, that the indignation was so great against him that the Federals changed him to another prison and permitted

him, doubtless, gladly, to slander his own men. Indignities were offered to these brave men all along the way to prison. At

Aurora, Indiana, as our men passed under guard, a crowd of big rough toughs, crowded around our men and belabored them much

as "miserable cowardly rebels," etc. Captain Printer of 55th Georgia, a big strong noble fellow finally said to the guards,

"Stop these cowardly curs, or we will." They stopped. Notwithstanding all these slanders about this Regiment it can receive

no higher endorsement, no greater meed of praise, no more complete refutation of slanders, than the fact that though in prison,

the dreadful prisons of the North, for 23 months, not a single man took the oath of allegiance to the North, although it was

offered to them often. Many of the command were sick, starved, frozen to death. Shot down for any or no pretense, all kinds

of insults and indignity were daily, monthly and yearly thrust into their faces. Disloyal indeed! Great Heaven!! Who will

dare say so again!!!

The whole history of the surrender of Cumberland Gap, as given out by

General Frazer and his staff, and one or two others who seem to have fallen under his influence, was a fabrication intended

to mislead the authorities at Richmond, never dreaming, perhaps, that it would come to the eyes of the public, and of those

who were on the ground and so unjustly slandered by his report.

We knew, or had been advised of the repeated demands for the surrender

of the Gap, and also that these demands had been refused, and had not the most remote idea that we were to be surrendered

until I was notified, as I have hereinbefore stated; and as I stated in my communication of 16 September, 1863, found on pages

636-37, Official Records of Union and Confederate Armies, Vol.51.

There was no insubordination among the troops of the Sixty-second North

Carolina Regiment, as far as I knew, and had there been, I certainly would have known it. Furthermore, there was no want of

courage, discipline or determination among the men. We expected the battle to come on every moment, and at no time during

the whole war did I ever see, or know, men more disappointed than these were when they found that they were surrendered without

an exhibition of their courage. Stalwart men actually cried like children when they found that they were surrendered and had

to submit to being made prisoners without defending their right and reputation, that

our commanding General never lost an opportunity to defame.

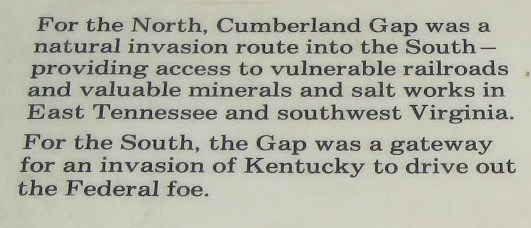

| High Resolution Map North Carolina Battlefields |

|

| High Resolution Map of Battle of Asheville, New Carolina, April 6, 1865 |

THE

CLOSING SCENES.

The Sixty-second North Carolina Regiment were the very last men to surrender

when the war closed. The fragment left of the regiment composed part of Palmer's Brigade at Asheville

10 March, 1865, and under General Martin aided to repulse Kirby's Brigade near that town 5 April, 1865. Many of them never

did take the oath of allegiance. The remnant of this regiment, along with other brave and noble men of the Old North State,

after General Lee's surrender in Virginia, resisted a Federal force on the French Broad, near Asheville, and held them at

bay for hours, until overcome by overwhelming forces and when forced to withdraw, under Colonel Clayton, did so and went to

their homes and never did take the oath of allegiance as then required by the Federal authorities. No braver or more noble

hearted men ever lived than those composing the Sixty-second North Carolina Regiment of Infantry.

B. G. McDowell

Bristol, Tenn.

30 May, 1901

Notes courtesy Matthew Parker

In late December 1862, while

guarding bridges and railroads in East Tennessee, three poorly armed companies (295 soldiers) of the 62nd North Carolina

Regiment were captured by a Union cavalry force of 3,000. The 62nd continued to serve in East Tennessee until 442 men of its men were surrendered to Union forces in the Cumberland

Gap on September 9, 1863, by General Frazer, who many consider a coward for not fighting nor trying to evade capture, but as

many as 200 soldiers from the 62nd evaded capture and in April 1864, the unit mustered 178 men in Asheville. The

bulk of the fighting at the Battle of Asheville, April 6, 1865, was shouldered by 175 of the unit's faithful warriors. As the Confederate and Union forces exchanged

volleys for five hours, Col. Clayton, commanding 62nd, local militia, soldiers on leave and others recovering from wounds

and illnesses, and a battery with two Napoleons, was eye witness to Kirby's Union brigade retreating toward Tennessee.

Lee surrendered to Grant just 3 days later on April 9, thus sealing the Confederacy's fate.

A record of any unit's events may be difficult to compile, because

many Confederate records were intentionally destroyed as the war neared its conclusion. For example, not a single

source survived the war to corroborate the total number of Confederate casualties, so best estimates have always been used.

The histories for Southern units were usually recorded by

the unit historian, but because the soldiers were ordered to burn their respective unit's records, lest the United States

use them as evidence for possible treason charges, the primary source for the Confederate unit is drawn from memoirs

written some 35 years after the war. From a single soldier's memoirs -- often written after 1900 -- is

the primary source for most Rebel regiments. Memoirs are problematic at best, because the soldier was prone to forget

important dates and actions which occurred so long ago. While embellishment and omission of facts were

common, as with all memoirs, the old warrior generally had physical and emotional scars, too, so not all acts

of commission and omission should be viewed under the light of judgment, but perhaps with empathy.

The record of events was basically a diary with entry dates, recording

unit location, any action that occurred, company transfers, as well as other material information. A regiment's

record of events, or sketch as many refer to it, sometimes offers battle casualty totals, but since it often lacks

accurate numbers it should not be used as a reliable source. Casualty reports for a battle were far from static,

because weeks and even months after a single engagement, soldiers who were initially recorded as wounded, may have had their

names moved into the mortally wounded category.

Missing in action after battle reports was at crisis proportions, because

many of the soldiers were captured and moved to prison camps, while others had in fact deserted. As a general rule by

the 1880s, the most quoted Civil War statisticians Fox, Dyer, and Phisterer, all agreed that the remaining missing in

action soldiers should be considered killed in action, which meant tens-of-thousands of soldiers, but since best estimates

have been applied to the total Confederate casualties, killed in action merely increased the estimated total number.

Recommended Viewing: The Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns. Review: The

Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns is the most successful public-television miniseries in American history. The 11-hour Civil War didn't just captivate a nation,

reteaching to us our history in narrative terms; it actually also invented a new film language taken from its creator. When

people describe documentaries using the "Ken Burns approach," its style is understood: voice-over narrators reading letters

and documents dramatically and stating the writer's name at their conclusion, fresh live footage of places juxtaposed with

still images (photographs, paintings, maps, prints), anecdotal interviews, and romantic musical scores taken from the era

he depicts. Continued below...

The Civil War uses all of these devices to evoke atmosphere and resurrect an event that many knew

only from stale history books. While Burns is a historian, a researcher, and a documentarian, he's above all a gifted storyteller,

and it's his narrative powers that give this chronicle its beauty, overwhelming emotion, and devastating horror. Using the

words of old letters, eloquently read by a variety of celebrities, the stories of historians like Shelby Foote and rare, stained

photos, Burns allows us not only to relearn and finally understand our history, but also to feel and experience it. "Hailed

as a film masterpiece and landmark in historical storytelling." "[S]hould be a requirement for every

student."

Recommended

Reading: The

Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (444 pages) (Louisiana State University Press)

(Updated edition: November 2007) Description: The Life of Johnny Reb does not merely describe the battles and skirmishes fought by

the Confederate foot soldier. Rather, it provides an intimate history of a soldier's daily life--the songs he sang, the foods

he ate, the hopes and fears he experienced, the reasons he fought. Wiley examined countless letters, diaries, newspaper accounts,

and official records to construct this frequently poignant, sometimes humorous account of the life of Johnny Reb. In a new

foreword for this updated edition, Civil War expert James I. Robertson, Jr., explores the exemplary career of Bell Irvin Wiley,

who championed the common folk, whom he saw as ensnared in the great conflict of the 1860s. Continued below...

About Johnny Reb:

"A Civil War classic."--Florida Historical Quarterly

"This book deserves to be on the shelf of every Civil War modeler and enthusiast."--Model

Retailer

"[Wiley] has painted with skill a picture of the life of the Confederate

private. . . . It is a picture that is not only by far the most complete we have ever had but perhaps the best of its kind

we ever shall have."--Saturday Review of Literature

Recommended

Reading: Confederate Military

History Of North Carolina: North Carolina

In The Civil War, 1861-1865. Description: The author, Prof. D. H. Hill, Jr., was the son of Lieutenant General

Daniel Harvey Hill (North Carolina produced only two lieutenant

generals and it was the second highest rank in the army) and his mother was the sister to General “Stonewall”

Jackson’s wife. In Confederate Military History Of North Carolina,

Hill discusses North Carolina’s massive task of preparing and mobilizing for the conflict; the many regiments and battalions

recruited from the Old North State; as well as the state's numerous contributions during the war. Continued below...

During Hill's

Tar

Heel State study, the reader begins with

interesting and thought-provoking statistical data regarding the 125,000 "Old

North State" soldiers that fought

during the course of the war and the 40,000 that perished. Hill advances with the Tar Heels to the first battle at Bethel, through numerous bloody campaigns and battles--including North Carolina’s

contributions at the "High Watermark" at Gettysburg--and concludes with Lee's surrender at

Appomattox.

Recommended Reading: Fields

of Honor: Pivotal Battles of the Civil War, by Edwin C. Bearss (Author), James McPherson (Introduction). Description: Bearss,

a former chief historian of the National Parks Service and internationally recognized American Civil War historian, chronicles

14 crucial battles, including Fort Sumter, Shiloh, Antietam, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, Sherman's march through the

Carolinas, and Appomattox--the battles ranging between 1861 and 1865; included is an introductory chapter describing John

Brown's raid in October 1859. Continued below...

Bearss describes the terrain, tactics, strategies, personalities,

the soldiers and the commanders. (He personalizes the generals and politicians, sergeants and privates.) The text is

augmented by 80 black-and-white photographs and 19 maps. It is like touring the battlefields without leaving home. A must

for every one of America's countless Civil War buffs, this major work will stand as an important

reference and enduring legacy of a great historian for generations to come. Also available in hardcover: Fields of Honor: Pivotal Battles of the Civil War . .

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in North Carolina.

Description: Numerous battles and skirmishes

were fought in North Carolina during the Civil War, and

the campaigns and battles themselves were crucial in the grand strategy of the conflict and involved some of the most famous

generals of the war. Continued below...

John Barrett presents the complete story of military engagements and battles across the state, including

the classical pitched battle of Bentonville--involving Generals Joe Johnston and William

Sherman--the siege of Fort Fisher, the amphibious campaigns on the

coast, and cavalry sweeps such as General George Stoneman's Raid. "Includes cavalry battles, Union Navy

operations, Confederate Navy expeditions, Naval bombardments, the land battles... [A]n indispensable edition." Also

available in hardcover: The Civil War in North Carolina.

|