|

CSS Albemarle

Civil War Ironclad History

CSS Albemarle

The Career of the Confederate Ram Albemarle. An Attempt to Run Down

an Iron-Clad With a Wooden Ship

By Edgar Holden, M.D., U.S.N.

(From The Century, Volume 36, Issue 3,

July 1888, pp. 427-432.)

The United States steamer Sassacus was one of several wooden side-wheel

ships, known as “double-enders,” built for speed, light draught, and ease of maneuver in battle, as they could

go ahead or hack with equal facility. She carried four 9-inch Dahlgren guns and two 100-pounder Parrott rifles. On the 5th

of May, 1864, this ship, while engaged, together with the Mattabesett, Wyalusing, and several smaller vessels, with the Confederate

iron-clad Albemarle in Albemarle Sound, was, under the command of Lieutenant-Commander F. A. Roe, and with all the speed attainable,

driven down upon the ram, striking full and square at the junction of its armored roof and deck. It was the first attempt

of the kind and deserves a place in history. This sketch is an endeavor to recall only the part taken in the engagement by

the Sassacus in her attempt to run down the ram.

One can obtain a fair idea of the magnitude of such an undertaking by remembering

that on a ship in battle you are on a floating target, through which the enemy’s shell may bring not only the carnage

of explosion but an equally unpleasant visitor — the sea. To hurl this egg-shell target against a rock would be dangerous,

but to hurl it against an iron-clad bristling with guns, or to plant it upon the muzzles of 100-pounder Brooke or Parrott

rifles, with all the chances of a sheering off of the iron-clad, and a subsequent ramming process about which no two opinions

ever existed, is more than dangerous.

| CSS Albemarle (Replica) |

|

| (Photographed in 2003) |

| CSS Albemarle Ironclad Gunboat |

|

| CSS Albemarle Ironclad Gunboat |

On the 17th of April, 1864, Plymouth, N. C., was attacked by the Confederates

by land and river. On the 20th it was captured, the ram Albemarle having sunk the Southfield and driven off the other Union

vessels.

On May 5th the Albemarle, with the captured steamer Bombshell and the steamer

Cotton Plant, laden with troops, came down the river. The double-enders Mattabesett, Sassacus, Wyalusing, and Miami, together

with the smaller vessels, Whitehead, Ceres, and Commodore Hull steamed up to give battle.

The Union plan of attack was for the large vessels to pass as close as possible

to the ram without endangering their wheels, deliver their fire, and then round to for a second discharge. The smaller vessels

were to take care of thirty armed launches, which were expected to accompany the iron-clad. The Miami carried a torpedo to

be exploded under the enemy, and a strong net or seine to foul her propeller.

All eyes were fixed on this second Merrimac as, like a floating fortress,

she came down the bay. A puff of smoke from her bow port opened the ball, followed quickly by another, the shells aimed skillfully

at the pivot-rifle of the leading ship, Mattabesett, cutting away rail and spars, and wounding six men at the gun. The enemy

then headed straight for her, in imitation of the Merrimac, but by a skillful management of the helm the Mattabesett rounded

her bow, closely followed by our own ship, the Sassacus, which at close quarters gave her a broadside of solid 9-inch shot.

The guns might as well have fired blank cartridges, for the shot skimmed off into the air, and even the 100-pound solid shot

from the pivot-rifle glanced from the sloping roof into space with no apparent effect. The feeling of helplessness that comes

from the failure of heavy guns to make any mark on an advancing foe can never be described. One is like a man with a bodkin

before a Gorgon or a Dragon, a man with straws before the wheels of Juggernaut.

To add to the feeling in this instance, the rapid firing from the different

ships, the clouds of smoke, the changes of position to avoid being run down, the watchfulness to get a shot into the ports

of the ram, as they quickly opened to deliver their well-directed fire, kept alive the constant danger of our ships firing

into or entangling each other. The crash of bulwarks and rending of exploding shells which were fired by the ram, but which

it was utterly useless to fire from our own guns, gave confused sensations of a general and promiscuous mode, rather than

a well-ordered attack; nevertheless the plan designed was being carried out, hopeless as it seemed. As our own ship delivered

her broadside, and fired the pivot-rifle with great rapidity at roof, and port, and hull, and smoke-stack, trying to find

a weak spot, the ram headed for us and narrowly passed our stern. She was foiled in this attempt, as we were under full headway,

and swiftly rounding her with a hard-port helm, we delivered a broadside at her consort, the Bombshell; each shot hulling

her. We now headed for the latter ship, going within hail.

Thus far in the action our pivot-rifle astern had had but small chance to

fire, and the captain of the gun, a broad-shouldered, brawny fellow, was now wrought up to a pitch of desperation at holding

his giant gun in leash, and as we came up to the Bombshell he mounted the rail, and, naked to the waist, he brandished a huge

boarding-pistol and shouted, “Haul down your flag and surrender, or we’ll blow you out of the water!” The

flag came down, and the Bombshell was ordered to drop out of action and anchor, which she did. Of this surrender I shall have

more to say farther on.

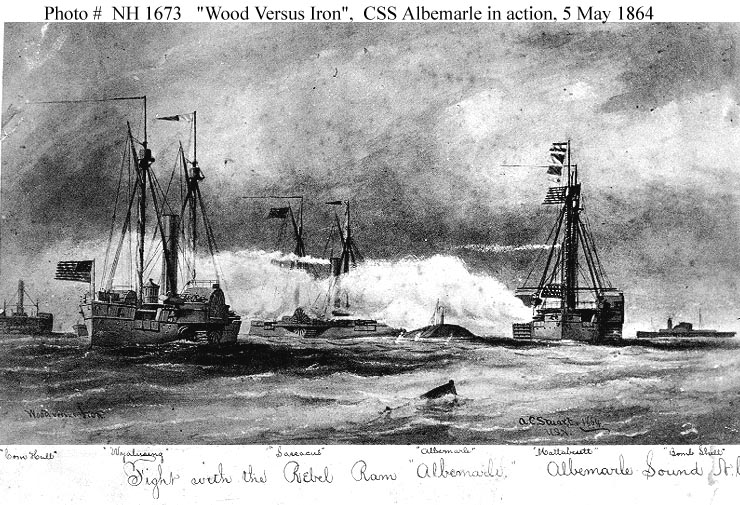

(Photograph) 19th Century photograph of an artwork by Acting Second Engineer

Alexander C. Stuart, USN, 1864. It shows CSS Albemarle engaging several Federal gunboats on Albemarle Sound, North

Carolina, on 5 May 1864. USS Sassacus is in left center, ramming the Confederate ironclad. Other U.S. Navy ships seen

are (from left): Commodore Hull, Wyalusing and Mattabesett. The Confederate transport Bombshell,

captured during the action, is in the right background. Albemarle was not significantly damaged during this action,

which left Sassacus disabled by a hit in one of her boilers.

| CSS Albemarle Ironclad Ram Cannon |

|

| CSS Albemarle Ironclad Ram Cannon |

Now came the decisive moment, for by this action, which was in reality a

maneuver of our commander, we had acquired a distance from the ram of about four hundred yards, and the latter, to evade the

Mattabesett, had sheered off a little and lay broadside to us. The Union ships were now on both sides of the ram with engines

stopped. Commander Roe saw the opportunity, which an instant’s delay would forfeit, and boldly met the crisis of the

engagement. To the engineer he cried, “Crowd waste and oil in the fires and back slowly! Give her all the steam she

can carry! To Acting-Master Boutelle he said, “Lay her course for the junction of the casemate and the hull!”

Then came four bells, and with full steam and open throttle the ship sprang forward like a living thing. It was a moment of

intense strain and anxiety. The guns ceased ward to the designated spot. Then came the firing, the smoke lifted from the ram,

and we order, “All hands lie down !“ and with a crash saw that every effort was being made to evade that shook

the ship like an earthquake, we the shock. Straight as an arrow we shot forward and struck full and square on the iron hull,

careening it over and tearing away our own bows, ripping and straining our timbers at the water- line. The enemy’s lights

were put out, and his men hurled from their feet, and, as we learned afterward, it was thought for a moment that it was all

over with them. Our ship quivered for an instant, but held fast, and the swift plash of the paddles showed that the engines

were uninjured. My own station was in the bow, on the main-deck, on a line with the enemy’s guns. Through the starboard

shutter, which had been partly jarred off by the concussion, I saw the port of the ram not ten feet away. It opened; and like

a flash of lightning I saw the grim muzzle of a cannon, the straining gun’s-crew naked to the waist and blackened with

powder; then a blaze, a roar and rush of the shell as it crashed through, whirling me round and dashing me to the deck.

Both ships were under headway, and as the ram advanced, our shattered bows

clinging to the iron casemate were twisted round, and a second shot from a Brooke gun almost touching our side crashed through,

followed immediately by a cloud of steam and boiling water that filled the forward decks as our overcharged boilers, pierced

by the shot, emptied their contents with a shrill scream that drowned for an instant the roar of the guns. The shouts of command

and the cries of scalded, wounded, and blinded men mingled with the rattle of small-arms that told of a hand-to-hand conflict

above. The ship surged heavily to port as the great weight of water in the boilers was expended, and over the cry, “The

ship is sinking!” came the shout, “All hands repel boarders on starboard bow!”

The men below, wild with the boiling steam, sprang to the ladder with pistol

and cutlass, and gained the bulwarks; but men in the rigging with muskets and hand grenades, and the well-directed fire from

the crews of the guns, soon baffled the attempt of the Confederates to gain our decks. To send our crew on the grated top

of the iron-clad would have been madness.

The horrid tumult, always characteristic of battle, was intensified by the

cries of agony from the scalded and frantic men. Wounds may rend, and blood flow, and grim heroism keep the teeth set firm

in silence; but to be boiled alive — to have the flesh drop from the face and hands, to strip off in sodden mass from

the body as the clothing is torn away in savage eagerness for relief, will bring screams from the stoutest lips. In the midst

of all this, when every man had left the engine room, our chief engineer, Mr. Hobby, although badly scalded, stood with heroism

at his post; nor did he leave it till after the action, when he was brought up, blinded and helpless, to the deck. I had often

before been in battle; had stepped over the decks of a steamer in the Merrimac fight when a shell had exploded, covering the

deck with fragments of human bodies, literally tearing to pieces the men on the small vessel as she lay alongside the Minnesota,

but never before had I experienced such a sickening sensation of horror as on this occasion, when the bow of the Sassacus

lay for thirteen minutes on the roof of the Albemarle. An officer of the Wyalusing says that when the dense smoke and steam

enveloped us they thought we had sunk, till the flash of our guns burst through the clouds, followed by flash after flash

in quick succession as our men recovered from the shock of the explosion.

In Commander Febiger’s report the time of our contact was said to

be “some few minutes.” To us, at least, there seemed time enough for the other ships to close in on the ram and

sink her, or sink beside her, and it was thirteen minutes as timed by an officer, who told me; hut the other ships were silent,

and with stopped engines looked on as the clouds closed over us in the grim and final struggle.

Captain French of the Miami, who had bravely fought his ship at close quarters,

and often at the ship’s length, vainly tried to get bows on, to come to our assistance and use his torpedo; but his

ship steered badly, and he was unable to reach us before we dropped away. In the mean time the Wyalusing signaled that she

was sinking—a mistake, but one that affected materially the outcome of the battle. We struck exactly at the spot for

which we had aimed; and, contrary to the diagram given in the naval report for that year, the headway of both ships twisted

our bows, and brought us broadside to broadside — our bows at the enemy’s stern and our starboard paddle—wheel

on the forward starboard angle of his casemate. Against the report mentioned, I not only place my own observation, but I have

in my possession the written statement of the navigator, Boutelle, now a member of Congress from Maine. At length we drifted off the ram, and our pivot-gun, which had been fired incessantly by Ensign

Mayer, almost muzzle to muzzle with the enemy’s guns, was kept at work till we were out of range.

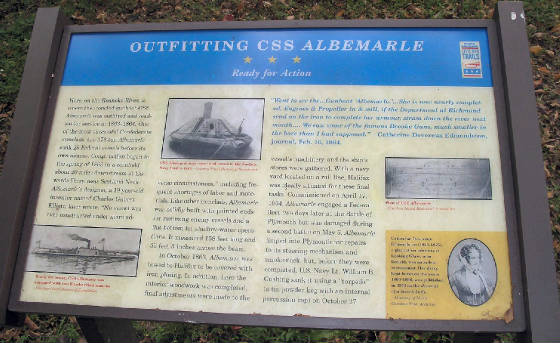

| CSS Albemarle Interpretive Marker |

|

| CSS Albemarle Interpretive Marker |

The official report says that the other ships were then got in line and

fired at the enemy, also attempting to lay the seine to foul his propeller — a task that proved, alas, as impracticable

as that of injuring him by the fire of the guns. While we were alongside, and had drifted broadside to broadside, our 9-inch

Dahlgren guns had been depressed till the shot would strike at right angles, and the solid iron would bound from the roof

into the air like marbles, and with as little impression. Fragments even of our 100-pound rifle-shots. at close range, came

back on our own decks. At dusk the ram steamed into the Roanoke River.

Had assistance been rendered during the long thirteen minutes that the Sassacus lay over the ports of the Albemarle, the heroism

of Commander Roe would have electrified the public and made his name, as it should be, imperishable in the annals of naval

warfare. There was no lack of courage on the other ships, and the previous loss of the Southfield, the signal from the Wyalusing

that she was sinking, the apparent loss of our ship, and the loss of the sounds of North Carolina if more were disabled, dictated

the prudent course they adopted.

| CSS Albemarle |

|

| CSS Albemarle and the sinking of a Confederate ironclad |

Of the official reports, which gave no prominence to the achievement of

Commander Roe and have placed an erroneous record on the page of history, I speak only with regret. He was asked to correct

his report as to the speed of our ship. He had said we were going at a speed of ten knots, and the naval report says, “He

was not disposed to make the original correction.” I should think not! — when the speed could only be estimated

by his own officers, and the navigator says clearly in his report eleven knots. We had perhaps the swiftest ship in the navy.

We had backed slowly to increase the distance; with furious fires and a gagged engine working at the full stroke of the pistons,—

a run of over four hundred yards, with eager and excited men counting the revolutions of our paddles; who should give the

more correct statement?

The ship first in the line claimed the capture of the Bombshell. The captain

of that vessel, afterward a prisoner on our ship. said he surrendered to the second ship in the line, viz., the Sassacus;

that the flag was not hauled down till he was ordered to do so by Commander Roe; and that no surrender had been intended till

the order came from the second vessel in the line.

Another part of the official report states that the bows of the double-enders

were all frail, and had they been armed would have been insufficient to have sunk the ram. If this were so, then was the heroism

of the trial the greater. Our bow, however, was shod with a bronze beak, weighing fully three tons, well secured to prow and

keel; and this was twisted and almost entirely torn away in the collision.

But what avails it to a soldier to dash over the parapet and seize the colors

of the enemy if his regiment halts outside the chevaux de frise? I’ve have always felt that a similar blow on the other

side, or a close environment of the heavy guns of the other ships, would have captured or sunk the ram. As it was, she retired,

never again to emerge for battle from the Roanoke River, and the object of her coming on the day of our engagement, viz.,

to aid the Confederates in an attack on New Berne, was defeated; but her ultimate destruction was reserved for the gallant

Lieutenant Cushing, of glorious memory.

Recommended Reading: The Hunt for the Albemarle:

Anatomy of a Gunboat War (Hardcover). Description: On a muddy waterway, once called the River of Death, James

Cooke and Charles Flusser met again after parting when the Civil War started. Once both navy lieutenants, they now were the

opponents in naval warfare. Confederate Navy Lieutenant James Cooke had as many years of active naval service as Charles Flusser

had years of living. Cooke was a devoted family man while Flusser was a bachelor with a mind for young Southern women, whiskey,

cigars, fast horses, and early promotion. Continued below...

The Confederate

ironclad Albemarle was the key to the river wars in North Carolina. Flusser's

search for this ship would determine the success or failure of the Union navy in securing the North Carolina coast and

rivers. James Cooke and the Confederates knew their only chance to break the blockade was with the new ironclad. The Hunt

for the Albemarle

is the dramatic story of these two men and their destiny. Both of these men shared one common characteristic. Each was willing

to die for the cause he believed was right.

Recommended Reading: Ironclads and Columbiads: The Coast

(The Civil War in North Carolina) (456 pages). Description: Ironclads and Columbiads covers some of the most

important battles and campaigns in the state. In January 1862, Union forces began in earnest to occupy crucial points on the

North Carolina coast. Within six months, Union army and

naval forces effectively controlled coastal North Carolina from the Virginia

line south to present-day Morehead City.

Union setbacks in Virginia, however, led to the withdrawal of many federal soldiers from North Carolina, leaving only enough

Union troops to hold a few coastal strongholds—the vital ports and railroad junctions. The South during the Civil War,

moreover, hotly contested the North’s ability to maintain its grip on these key coastal strongholds.

Recommended Reading: Storm

over Carolina: The Confederate Navy's Struggle for Eastern North Carolina. Description: The struggle for control of the eastern

waters of North Carolina during the War Between the States

was a bitter, painful, and sometimes humiliating one for the Confederate navy. No better example exists of the classic adage,

"Too little, too late." Burdened by the lack of adequate warships, construction facilities, and even ammunition, the

South's naval arm fought bravely and even recklessly to stem the tide of the Federal invasion of North

Carolina from the raging Atlantic. Storm

Over Carolina is the account of the Southern navy's struggle in North

Carolina waters and it is a saga of crushing defeats interspersed with moments of brilliant and even

spectacular victories. It is also the story of dogged Southern determination and incredible perseverance in the face

of overwhelming odds. Continued below...

Recommended

Reading: Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads. Description: William N. Still's book is rightfully referred to as the standard of Confederate Naval history.

Accurate and objective accounts of the major and even minor engagements with Union forces are combined with extensive background

information. This edition has an enlarged section of historical drawings and sketches. Mr. Still explains the political background

that gave rise to the Confederate Ironclad program and his research is impeccable. An exhaustive literature listing rounds

out this excellent book. While strictly scientific, the inclusion of historical eyewitness accounts and the always fluent

style make this book a joy to read. This book is a great starting point.

Recommended

Reading: A History of Ironclads: The Power of Iron over Wood. Description: This

landmark book documents the dramatic history of Civil War ironclads and reveals how ironclad warships revolutionized naval

warfare. Author John V. Quarstein explores in depth the impact of ironclads during the Civil War and their colossal effect

on naval history. The Battle of Hampton Roads was one of history's greatest naval engagements. Over the course of two days

in March 1862, this Civil War conflict decided the fate of all the world's navies. It was the first battle between ironclad

warships, and the 25,000 sailors, soldiers and civilians who witnessed the battle vividly understood what history would soon

confirm: wars waged on the seas would never be the same. Continued below…

About the Author: John V. Quarstein is an award-winning author and historian. He is director

of the Virginia

War Museum in Newport News and chief historical advisor for The Mariners' Museum's new USS Monitor Center

(opened March 2007). Quarstein has authored eleven books and dozens of articles on American, military and Civil War history,

and has appeared in documentaries for PBS, BBC, The History Channel and Discovery Channel.

Recommended

Reading: Civil War Ironclads: The U.S.

Navy and Industrial Mobilization (Johns

Hopkins Studies in the History of Technology). Description:

"In this impressively researched and broadly conceived study, William Roberts offers the first comprehensive study of one

of the most ambitious programs in the history of naval shipbuilding, the Union's ironclad

program during the Civil War. Perhaps more importantly, Roberts also provides an invaluable framework for understanding and

analyzing military-industrial relations, an insightful commentary on the military acquisition process, and a cautionary tale

on the perils of the pursuit of perfection and personal recognition." - Robert Angevine, Journal of Military History "Roberts's

study, illuminating on many fronts, is a welcome addition to our understanding of the Union's industrial mobilization during

the Civil War and its inadvertent effects on the postwar U.S. Navy." - William M. McBride, Technology and Culture"

Recommended

Reading: A History of the Confederate Navy

(Hardcover). From Publishers Weekly: One of the most prominent European scholars of the Civil War weighs in with a provocative

revisionist study of the Confederacy's naval policies. For 27 years, University of Genoa history professor Luraghi (The Rise

and Fall of the Plantation South) explored archival and monographic sources on both sides of the Atlantic to develop a convincing

argument that the deadliest maritime threat to the South was not, as commonly thought, the Union's blockade but the North's

amphibious and river operations. Confederate Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory, the author shows, thus focused on protecting

the Confederacy's inland waterways and controlling the harbors vital for military imports. Continued below…

As a result,

from Vicksburg

to Savannah to Richmond, major

Confederate ports ultimately were captured from the land and not from the sea, despite the North's overwhelming naval strength.

Luraghi highlights the South's ingenuity in inventing and employing new technologies: the ironclad, the submarine, the torpedo.

He establishes, however, that these innovations were the brainchildren of only a few men, whose work, although brilliant,

couldn't match the resources and might of a major industrial power like the Union. Nor did

the Confederate Navy, weakened through Mallory's administrative inefficiency, compensate with an effective command system.

Enhanced by a translation that retains the verve of the original, Luraghi's study is a notable addition to Civil War maritime

history. Includes numerous photos.

|