|

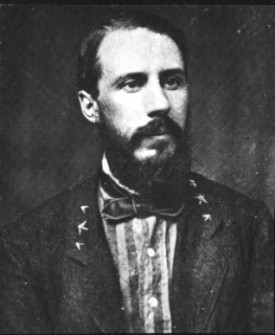

E. Porter Alexander

| E. Porter Alexander |

|

EDWARD PORTER ALEXANDER

(Right) Photograph Courtesy Library of Congress

Edward Porter Alexander

May 26, 1835 - April 28, 1910

Edward Porter Alexander

was born on May 26, 1835, in Washington, Georgia,

to Adam Leopold Alexander and Sarah Hillhouse Gilbert Alexander. Alexander, known to his

friends as Porter, was the sixth of eight children. He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1857, third

in his class of 38 cadets, and was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant of Engineers. He briefly taught engineering and

fencing at the academy before he was ordered to report to Brig. Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston for the Utah War expedition. The

mission was terminated before he reached Johnston, so Alexander returned to West Point, where he participated in a number

of weapons' experiments and worked as an assistant to Major Albert J. Myer, the first U.S. Army Signal Officer and the inventor

of the "wig-wag" signal flag, or "aerial telegraphy", code.

Alexander met Bettie Mason of Virginia in 1859 and they married on April 3, 1860. They had

six children: Bessie Mason (born 1861), Edward Porter II and Lucy Roy (twins, born 1863), an unnamed daughter (1865, died

in infancy prior to naming), Adam Leopold (1867), and William Mason (1868).

Alexander's final assignment for the U.S. Army was in the Washington Territory at Fort Steilacoom

and at Alcatraz Island near San Francisco, California. After learning of the secession of his home state of Georgia, Alexander resigned his U.S. Army commission on May 1, 1861, to join the

Confederate Army as a captain of engineers. While organizing and training new recruits to form a Confederate signal service,

he was ordered to report to Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard at Manassas Junction, Virginia. He became the Chief Engineer and

Signal Officer on June 3. At the First Battle of Bull Run, he made history by transmitting the first message in combat

using signal flags over a long distance. Stationed atop "Signal Hill" in Manassas,

Alexander saw Union troop movements and signaled to the brigade under Col. Nathan "Shanks" Evans, "Look out for your left,

your position is turned", which meant that they were in danger of being attacked on their left flank. Upon receiving a similar

message, Generals Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston sent timely reinforcements that turned the tide of battle in the Confederates'

favor.

Alexander was promoted to

major on July 1 and lieutenant colonel on December 31, 1861. During much of this period he was chief of ordnance in (what

would eventually be named) the Army of Northern Virginia under Johnston, and was also active in signal work and intelligence gathering,

dealing extensively with spies operating around Washington,

D.C.

During

the early days of the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, Alexander continued as chief of ordinance under Johnston, although he managed to participate in combat at the Battle of Williamsburg and

was commended by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet for his actions there. When Gen. Robert E. Lee assumed command of the army, Alexander pre-positioned ordinance for Lee's offensive

in the Seven Days Battles. He continued his intelligence gathering

by volunteering to go up in a hot air balloon at Gaines' Mill on June 27, ascending

several times and returning with valuable intelligence regarding the position of the Union Army. Alexander continued in ordnance

for the Northern Virginia Campaign (Second Battle of Bull Run) and the Maryland Campaign (Antietam).

Porter Alexander is best known

as an artilleryman that played a prominent role in many important battles of the war. Beginning

on November 7, 1862, he served in different artillery capacities for the First (Longstreet's) Corps of the Army of Northern

Virginia. He was promoted to colonel on December 5, 1862. He was instrumental in arranging the artillery in defense of Marye's

Heights at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, which proved to be the decisive factor in the Confederate victory.

While the rest of Longstreet's corps was located around Suffolk, Virginia, Alexander

accompanied "Stonewall" Jackson on his flanking march at the Battle of Chickamauga in May 1863. And his artillery placements in Hazel Grove at the Battle of Chancellorsville

proved decisive.

But Alexander's most famous engagement

was on July 3, 1863, at the Battle of Gettysburg; he commanded the artillery for Longstreet's corps. On that day, he was

effectively in control of the artillery for the full army (despite Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton's formal role as chief

of artillery under Lee). He conducted a massive two-hour bombardment, arguably the largest in the war, using between 150 and

170 guns against the Union position on Cemetery Ridge. Under General Longstreet's orders, Alexander's artillery provided covering

fire during General George Pickett's famous charge. Prior to Pickett's advance, the young colonel had to ascertain whether the Union artillery defenses

had been effectively suppressed.

After Gettysburg, Alexander accompanied

the First Corps to northern Georgia in

the fall of 1863 to reinforce Gen. Braxton Bragg for the Battle of Chickamauga. He personally arrived too late to participate in the battle, but served as

Longstreet's chief of artillery in the subsequent Knoxville Campaign and in the Department of East Tennessee in early 1864.

He returned with the corps to Virginia for the remainder

of the war, and was promoted to brigadier general on February 26, 1864. He served in all the battles of the Overland Campaign, and when Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was flanking Lee's army in order to

cross the James River and assault Petersburg, Alexander was

able to move his artillery quickly through the lines and had his guns in place to repel the main attack.

During the Siege of Petersburg, Alexander had to adapt his artillery tactics to trench warfare, including experimentation

with various types of mortars. He was convinced that the Union forces were attempting to tunnel under the Confederate lines,

but before he was able to act on this, he was wounded in the shoulder by a sharpshooter. As he departed on medical leave to

Georgia, he informed Gen. Lee of his suspicion. Unsuccessful

attempts were made to locate the tunneling activity. The resulting Battle of the Crater caught the Confederates by surprise, although it ended in a significant

Union defeat. Alexander returned to the Army in February 1865 and supervised the defenses of Richmond

along the James River. He retreated with Lee's army during the Appomattox Campaign.

Prior to surrendering the

Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, Alexander made the famous proposal to Robert E. Lee that the army should

disperse into the hills for a guerrilla war.

After the American Civil

War, he taught mathematics at the University of South Carolina

in Columbia, and then served in executive positions with the Charlotte,

Columbia, and Augusta Railroad (executive superintendent), the Savannah

and Memphis Railroad (president), and the Louisville and Nashville

Railroad (president). He and President Grover Cleveland were friends. In May 1897, Cleveland

sent Alexander to be the arbiter of a boundary dispute between Nicaragua

and Costa Rica. Also, in preparation for a possible canal to be dug across

Central America, he spent two years surveying and supervising the boundary. He completed

the work to the great acclaim of the two governments, and returned to the U.S.

in October 1899. His wife Bettie became ill while he was in Nicaragua

and she died on November 20, 1899. In October 1901, Alexander married Mary Mason, his late wife's niece.

Alexander was a respected author

following the war. He wrote many magazine articles and two major books: Military Memoirs of a Confederate, A Critical Narrative

(published in 1907); and Fighting for the Confederacy, The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander (posthumous,

1989).

Porter died on April 28, 1910, at Savannah, Georgia,

and is buried in Magnolia Cemetery, Augusta, Georgia.

(Sources and relate reading listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended Reading: Fighting for

the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander. Description: Originally published by UNC Press in 1989, Fighting for the Confederacy is one of

the richest personal accounts in all of the vast literature on the Civil War. Alexander was involved in nearly all of the

great battles of the East, from First Manassas through Appomattox,

and his duties brought him into frequent contact with most of the high command of the Army of Northern Virginia, including

Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and James Longstreet.

Continued below...

No other Civil

War veteran of his stature matched Alexander's ability to discuss operations in penetrating detail—this is especially

true of his description of Gettysburg. His narrative is also remarkable for its utterly candid appraisals of leaders

on both sides.

Related Reading:

Recommended Reading:

Military Memoirs Of A Confederate, by Edward Porter Alexander. Description: General Edward Porter Alexander was the master gunner of the Confederacy,

and undeniably one of the great American artillerists. He was involved in nearly all of the great battles of the East, from

First Manassas through Appomattox; on the second day at Gettysburg,

Alexander’s battalion executed one of the greatest artillery charges of the war; Longstreet relied upon him for reconnaissance,

and Stonewall Jackson wanted him made an infantry general. Continued below...

Consequently,

Lee, at times, would confide in this young general commonly referred to as E. Porter Alexander.

Recommended

Reading: Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command (912 pages).

Description: Hailed as one of the greatest Civil War

books, this exhaustive study is an abridgement of the original three-volume version. It is a history of the Army

of Northern Virginia from the first shot fired to the surrender at Appomattox

- but what makes this book unique is that it incorporates a series of biographies of more than 150 Confederate officers. The

book discusses in depth all the tradeoffs that were being made politically and militarily by the South. Continued below...

The book does

an excellent job describing the battles, then at a critical decision point in the battle, the book focuses on an officer -

the book stops and tells the biography of that person, and then goes back to the battle and tells what information the officer

had at that point and the decision he made. At the end of the battle, the officers decisions are critiqued based on what he

"could have known and what he should have known" given his experience, and that is compared with 20/20 hindsight. "It is an

incredibly well written book!"

Recommended Reading: Confederate

Artilleryman 1861-65 (Warrior). Description:

This title guides the reader through the life and experiences of the Confederate cannoneer - where he came from; how he trained

and lived; how he dressed, ate and was equipped; and how he fought. Insights into the real lives of history's fighting men,

and packed with full color illustrations, highly detailed cutaways, and exploded artwork. Continued below...

When the Civil

War began in 1861, comparatively few Southern men volunteered for service in the artillery: most preferred the easily accessible

glory of the infantry or cavalry. Yet, the artillerist quickly earned the respect of their fellow soldiers, and a reputation

for being able to "pull through deeper mud, ford deeper springs, shoot faster, swear louder ... than any other class of men

in the service." Given that field artillery was invariably deployed in front of the troops that it was supporting, the artillerymen

were exposed to a high level of enemy fire, and losses were significant.

Recommended Reading: The Artillery

of Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: The battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the apex of the Confederacy's final major invasion of the North,

was a devastating defeat that also marked the end of the South's offensive strategy against the North. From this battle until

the end of the war, the Confederate armies largely remained defensive. The Artillery of Gettysburg is a thought-provoking

look at the role of the artillery during the July 1-3, 1863 conflict. Continued below...

During the Gettysburg campaign, artillery had already gained the respect

in both armies. Used defensively, it could break up attacking formations and change the outcomes of battle. On the offense,

it could soften up enemy positions prior to attack. And even if the results were not immediately obvious, the psychological

effects to strong artillery support could bolster the infantry and discourage the enemy. Ultimately, infantry and artillery

branches became codependent, for the artillery needed infantry support lest it be decimated by enemy infantry or captured.

The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had modified its codependent command system in February 1863. Prior to that, batteries

were allocated to brigades, but now they were assigned to each infantry division, thus decentralizing its command structure

and making it more difficult for Gen. Robert E. Lee and his artillery chief, Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, to control their

deployment on the battlefield. The Union Army of the Potomac had superior artillery capabilities

in numerous ways. At Gettysburg, the Federal artillery had

372 cannons and the Confederates 283. To make matters worse, the Confederate artillery frequently was hindered by the quality

of the fuses, which caused the shells to explode too early, too late, or not at all. When combined with a command structure

that gave Union Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt more direct control--than his Southern counterpart had over his forces--the Federal

army enjoyed a decided advantage in the countryside around Gettysburg. Bradley

M. Gottfried provides insight into how the two armies employed their artillery, how the different kinds of weapons functioned

in battle, and the strategies for using each of them. He shows how artillery affected the “ebb and flow” of battle

for both armies and thus provides a unique way of understanding the strategies of the Federal and Union

commanders.

Bibliography: Alexander, Edward P., and Gallagher, Gary W. (editor), Fighting for the Confederacy:

The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander, University of North Carolina Press, 1989; Brown, J. Willard,

The Signal Corps, U.S.A. in the War of the Rebellion, U.S. Veteran Signal Corps Association, 1896 (reprinted by Arno Press,

1974); Eicher, David J., The Civil War in Books: An Analytical

Bibliography, University of Illinois, 1997; Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University

Press, 2001; Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., "Edward Porter Alexander", Encyclopedia of the American Civil War:

A Political, Social, and Military History, Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000;

Edward Porter Alexander, a biography by Maury Klein, University of Georgia Press, 1971; Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies.

|