|

Longstreet's Grand Assault

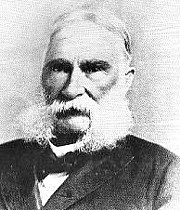

General James Longstreet

(January 8, 1821 – January 2, 1904)

"Never Was I So Depressed."

James Longstreet on Pickett’s Charge

| General James Longstreet |

|

| (Library of Congress) |

James Longstreet was born in South Carolina in 1821, and he graduated West Point in 1842. During the Mexican-American War in 1847, he experienced extensive front line combat service in both the northern and southern theaters of operations,

where he led detachments that helped capture two Mexican forts guarding Monterey (Longstreet also engaged in street

fighting in Monterey). At Churubusco, he planted the regimental colors on the walls of the fort and saw action at Casa Marta,

near Molino del Ray. On August 13, 1847, Longstreet was wounded during the assault on Chapaltepec while "in the act of discharging

the piece of a wounded man. He was always in front with the colors. His high and gallant bearing won the applause of all who

saw him." The general remained in service after the war and became one of the "Old Army Regulars"- men who served from post

to post in a less than glamorous peace-time army. On May 9, 1861, Longstreet resigned his commission

from the U.S. Army to join the new Confederacy. Appointed brigadier general on June 17, 1861, and a major general on October

7, 1861, Longstreet commanded troops at First Manassas, Seven Pines, the Seven Days Campaign, Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. He was appointed a lieutenant general on October 9, 1862,

one day before Thomas J. Jackson's promotion, making Longstreet the senior lieutenant general in the Confederate

Army.

| Lt. Col. Moxley Sorrel |

|

| (Library of Congress) |

Lt. Colonel G. Moxley Sorrel, Longstreet’s Chief of Staff, described his commander as, "a most striking

figure... a soldier every inch, and very handsome, tall and well proportioned, strong and active, a superb horseman and with

an unsurpassed soldierly bearing, his features and expressions fairly matched; eyes, glint steel blue, deep and piercing."

Captain Thomas J. Goree, Longstreet’s aide, thought the general was, "one of the kindest, best hearted men I ever knew."

Longstreet could appear "short and crabbed" to some people but not when in the presence of ladies, at the table, or on the

field of battle. "At any of these places, he has a complacent smile on his countenance, and seems to be one of the happiest

men in the world." Even though Longstreet was usually very "sociable and agreeable" at these events, there were times when

he, "is as grim as you please." But Goree noted that this usually happened when the general, "was not very well or something

has not gone to suit him." The staff came to discover that there were times when it was best to leave Longstreet alone unless,

"he is in a talkative mood. He has a good deal of the roughness of the old soldier about him."

| Capt. T.J. Goree |

|

| (Library of Congress) |

Goree believed that Longstreet’s forte as an officer consisted, "in the seeming ease with which he

can handle and arrange large numbers of troops, as also with the confidence and enthusiasm with which he seems to inspire

them.... if he is ever excited, he has a way of concealing it, and always appears as if he has the utmost confidence in his

own ability to command and in that of his troops to execute. In a fight he is a man of but very few words, and keeps at all

time his own counsels.... He is very reserved and distant towards his men, and very strict, but they all like him."

The general's contemporaries also considered "Old Peter" to be a grudging,

yet professional soldier. General Robert E. Lee considered him "a Capital soldier" and expressed confidence in his abilities. Their headquarters were often

established near each other and the two became close friends. Longstreet described his relations with Lee as one "of confidence

and esteem, official and personal, which ripened into stronger ties as the mutations of war bore heavier upon us." Lee wanted

his views "in moves of strategy and general policy, not so much for the purpose of having his views approved and confirmed

as to get new light, or channels for new thought, and was more pleased when he found something that gave him new strength

than with efforts to evade his questions by compliments." Lt. Colonel Arthur J. L. Fremantle, a British military observer

who accompanied Longstreet during the Gettysburg Campaign, noted that the relations between the two, "are quite touching - they are almost always together.... It is impossible

to please Longstreet more than by praising Lee. I believe these two generals to be as little ambitious and as thoroughly unselfish

as any men in the world. Both long for a successful termination of the war, in order that they may retire into obscurity."

On more than one occasion during the war, Longstreet was to prove his ability

to organize, coordinate, and direct a massive offensive strike as long as the situation suited him. At Second Manassas, Longstreet's

Corps struck the Union left with a solid line; the battle resulted in Longstreet's casualties being higher in three hours

than what Jackson's had been in three days. However, Longstreet's overwhelming assault broke the Union army in half and

sent it reeling from the field. The situation at Gettysburg was very different than these circumstances, which did not suit

'Longstreet the strategist.'

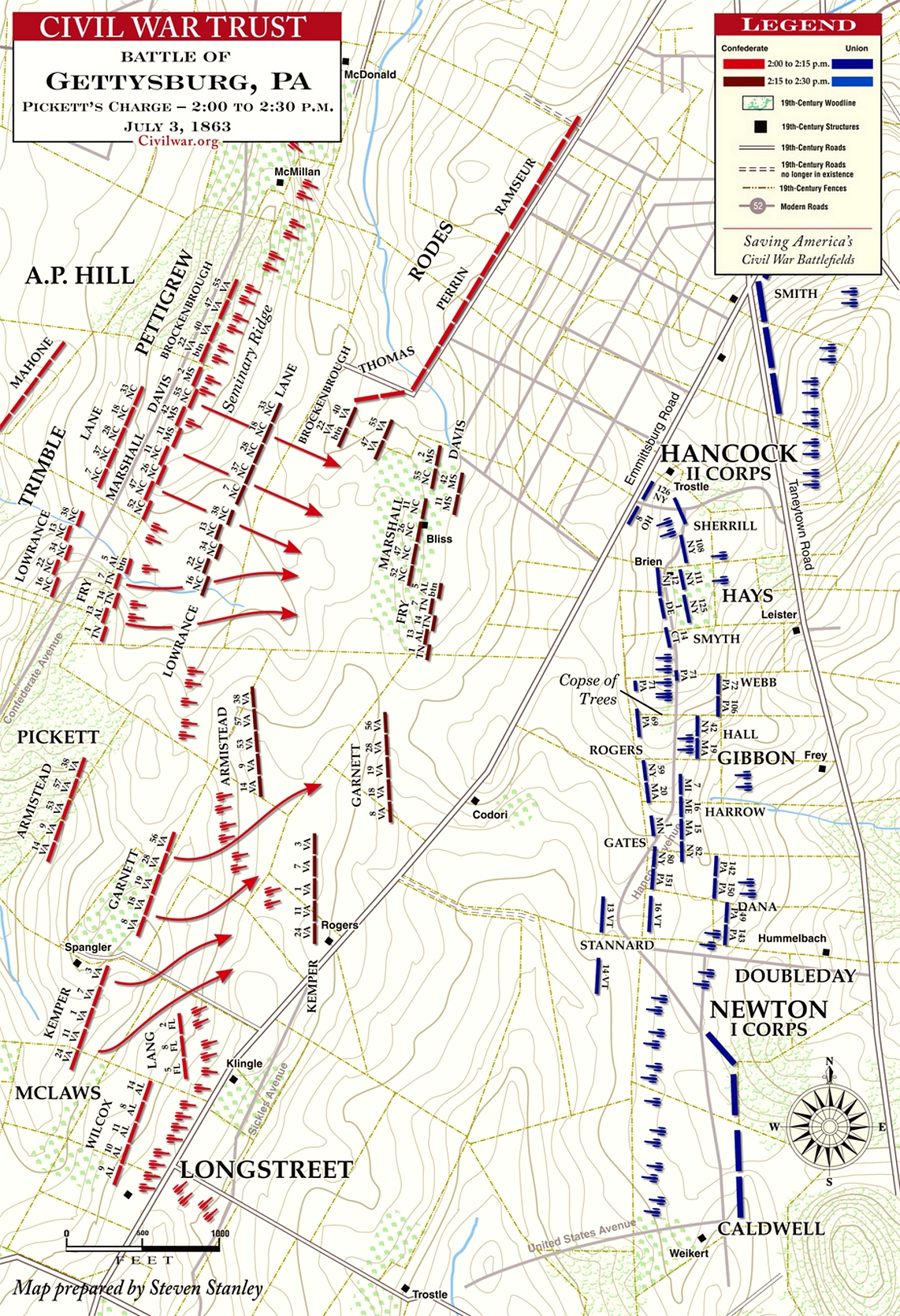

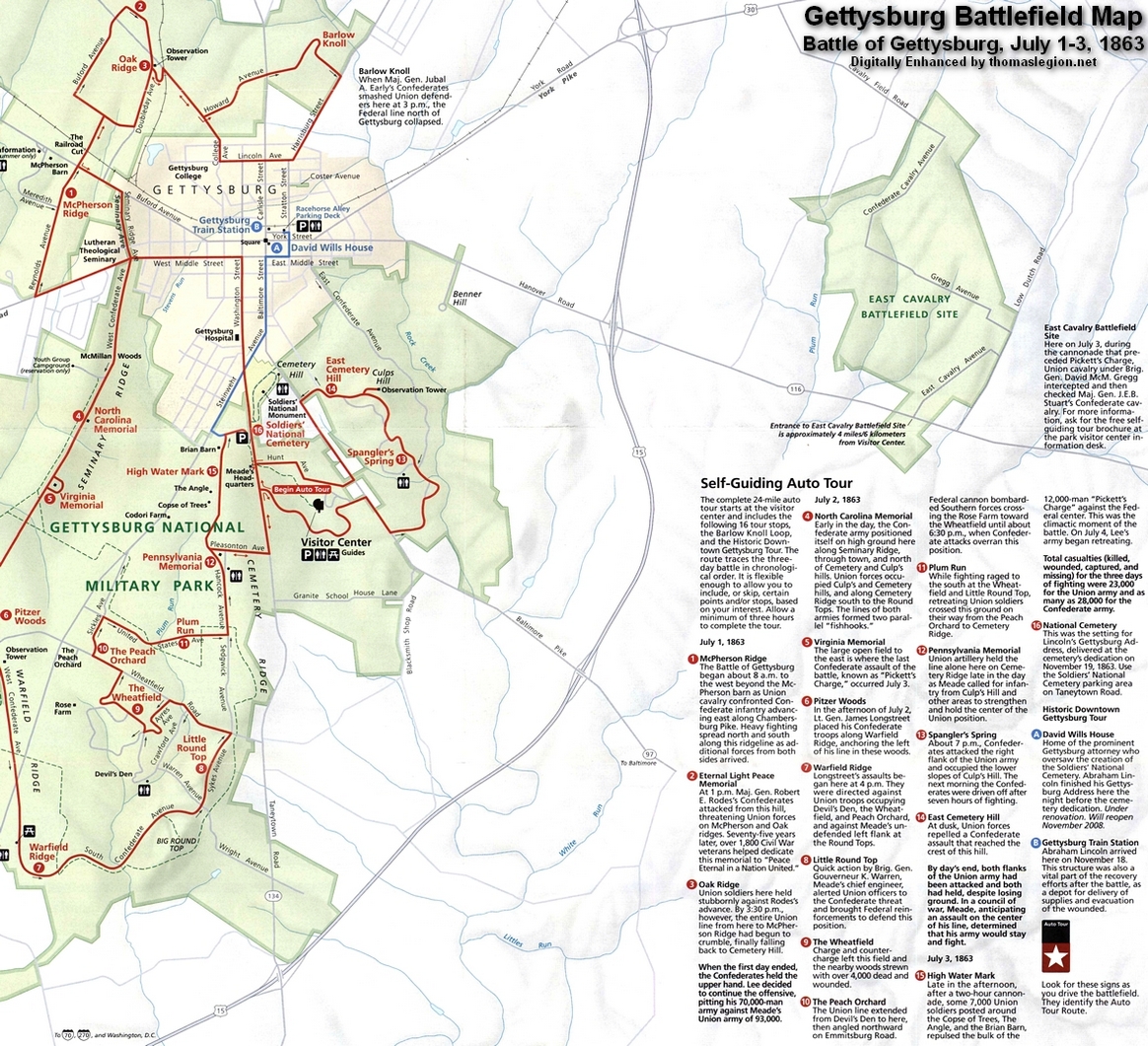

| Longstreet's Grand Assault |

|

| Period Map of Pettigrew-Pickett Charge at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863 |

Lee’s basic battle plan for July 2 was to launch an attack all along

the Union line. Longstreet's Corps was to envelope and drive in the Union left. Lt. General A. P. Hill's troops were "to threaten

the enemy’s center", and cooperate in Longstreet’s attack while Lt. General Richard S. Ewell's was "to make a

simultaneous demonstration upon the enemy’s right, to be converted into a real attack should opportunity offer." By

the end of July 2, two of Longstreet's divisions under Major General John B. Hood and Major General Lafayette McLaws had smashed the Union left at the Peach Orchard and Devil's Den, but had failed to take Little Round Top. Brig. General A. R. Wright, leading a brigade of Georgians late that day, claimed to have penetrated the Union line just

south of a copse of trees near the Union center on Cemetery Ridge, but could not hold it. Major General Edward Johnson’s Division of Ewell’s Corps captured some of the Union entrenchments

on the lower slopes of Culp's Hill. The initial reports of these successes caused Lee to believe that, "with proper concert of action...we should ultimately

succeed, and it was accordingly determined to continue the attack. The general plan was unchanged."

Lee planned a continuation of his July 2 battle plan for

July 3, with the troops launching their attacks from the positions gained that day. The only alteration was to be the addition of

Major General George E. Pickett’s Division, of Longstreet’s Corps, which had not yet been engaged. The major drawback

to Lee’s plan was his failure to meet personally with his three corps commanders on the evening of July 2 to ensure

that they understood his intentions and their role in the coming battle. Longstreet also admitted that contrary to his usual

practice of meeting with Lee, he only sent a message on the July 2 action. It is not clear what, if any, orders Longstreet

may have received on that evening. Without formal orders from Lee, Longstreet probably felt Lee's previous directions were

vague enough for him to use his discretion in execution. Given this seeming lack of communication it is hard to see how Lee

hoped to achieve his "proper concert of action." In any event, Lee’s plan for July 3 was disrupted by the actions of

the Army of the Potomac. As dawn approached at around 4:30 A.M., the Union Twelfth Corps artillery in the Culp’s Hill area opened fire on Johnson's

men in preparation of a planned Union counter-attack. This action forced Ewell to launch his attack with Johnson’s Division

before the rest of the army was ready. Half an hour after the attack started, and while Johnson was heavily engaged and unable

to withdraw, Ewell received word that Longstreet would not be able to attack until at least 10:00 A.M. By then it would be

too late for Ewell who was hard pressed and forced to cease his attacks by approximately 11:00 A.M.

Meanwhile, General Longstreet had been up most of the night and reported that

his scouts had found a route around the left flank of the Union army that would enable him to attack the Round Tops in flank and reverse. Admittedly, this "would have been a slow process, probably, but I think not very difficult." Just after

Longstreet issued orders for a flank march, or while he was in the process, he was joined by Lee who countermanded this major

change in Lee’s battle plans. Due to the circumstances at Culp's Hill, Lee was forced to rethink his plan of action on July 3. Shortly after canceling Longstreet’s proposed flank move,

Lee met with Longstreet, Hill, and Major General Henry Heth. Lee’s staff- Colonel A. L. Long, Major Charles S. Venable,

and possibly Colonel Walter Taylor also attended. Lee proposed using Longstreet’s entire corps to attack the Union center

but Longstreet objected that Hood and McLaws, "were holding a mile along the right of my line against twenty thousand men,

who would follow their withdrawal, strike the flank of the assaulting column, crush it." Lee agreed to leave them in place

and assign other troops to join Pickett's Division in the attack. It may have been Hill, or possibly Heth, offered Heth’s Division and two brigades from Major General

William D. Pender’s Division as substitutes. These troops were already in the right position to join Pickett. As Heth

had been seriously wounded on July 1, his division was under the temporary command of Brig. General James Johnston Pettigrew.

Brig. General James H. Lane was in temporary command of Pender’s Division after his being wounded on July 2. Lane was subsequently relieved by

Major General Isaac R. Trimble. Lee also indicated that he wanted to precede the attack with a massive artillery bombardment

to drive off some of the Union batteries and demoralize the Union infantry. The objective point was to be a salient angle

in the Union line between Ziegler's Grove and a distinctive smaller grove of trees to the south.

The main attack was to be made by Pickett, Pettigrew and two brigades under

Trimble. Brig. General Cadmus Wilcox’s Brigade, Anderson’s Division of Hill’s Corps, was ordered to move

in rear of Pickett’s right flank and "to protect it from any force that the enemy might attempt to move against it."

Colonel David Lang, commanding Perry's Brigade of Anderson’s Division, stated that at daylight he received orders from Anderson, "to connect my right with General

Wilcox’s left, and conform my movements during the day to those of his brigade." He also stated that he was told that

he "would receive no further orders." A total of about 12,891 officers and men were in the attacking column and under the

tactical command of Longstreet. What other troops were to be involved, and how much authority Longstreet had over them is

more difficult to establish.

Lee’s staff officers, most notably A. L. Long and Walter Taylor, maintained

that Lee expected Longstreet to use his whole corps to support the attack, but there is no direct or contemporary evidence

to this effect. Hood’s Division, commanded by Brig. General Evander Law since Hood’s wounding, was deployed to

protect the army’s extreme right flank. In McLaws’ Division, Kershaw's Brigade was stationed in the area of the Peach Orchard, Wofford’s Brigade was west of the Emmitsburg Road, and Semmes’

Brigade was in the area of Rose’s Woods. Barksdale’s Brigade was deployed in a skirmish formation from Trostle’s

Woods to somewhere between the Klingle House and the Rogers’ House. Major James Dearing, stationed with his battalion

in the area of the Rogers’ House, stated that during the morning he had no infantry to protect his front and had to

order Captain R. M. Stribling’s battery to drive in the advance of Union skirmishers. The units of Hood and McLaws were

thus not positioned to join the attacking column and none of the commanders reported receiving any orders to do so.

Major General Robert E. Rodes' Division of Ewell’s Corps, was positioned

in Long Lane, north of the Bliss Farm and east of Seminary Ridge, with the brigades of Doles, Ramseur, and Iverson (about

2,337 men). Rodes reported that his orders for July 3 were the same as for July 2, to "co-operate with the attacking force

as soon as any opportunity of doing so with good effect was offered." Rodes said nothing about being directly under Longstreet’s

command. A. P. Hill recorded that he was, "directed to hold my line with Anderson’s division and the half of Pender’s...

Anderson had been directed to hold his division ready to take advantage of any success which might be gained by the assaulting

column, or to support it, if necessary." Major Joseph A. Engelhard, Assistant Adjutant-General of Pender’s Division,

reported that only two brigades, Lane and Scales, were to report to Longstreet. Pender’s other two brigades under Brig. General Edward L. Thomas and Colonel

Abner Perrin, were located in Long Lane to the right, or south, of Rodes Division. Neither reported what their roles were

to be in the assault. The only troops designated for the attack and thus directly under Longstreet’s authority were

Pickett, Pettigrew, Trimble, Wilcox, and Lang. It does appear that if the attack succeeded, Lee intended for other units to

exploit the break-through and the anticipated Union retreat, a natural action which Lee’s army had executed at Second

Manassas and Chancellorsville with some success.

Once Lee had determined the point of attack and the troops to make it, Longstreet

still raised objections. Colonel E. P. Alexander, responsible for directing most of the Confederate guns on Longstreet's front on July 3, wrote his father that Longstreet

opposed the attack because the, "enemy’s position was so powerful, entirely sweeping the 1200 yards over which we had

to advance, that it was of doubtful success," adding that Longstreet announced, "General, I have been a soldier all my life.

I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should

know as well as any one, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take

that position." Whether these were Longstreet’s exact words or not is unimportant. What is important is that Longstreet

had no faith in the plan, did not believe it would work, and felt justified in telling Lee so. Longstreet later wrote that

Lee, "knew that I did not believe that success was possible; that care and time should be taken to give the troops the benefit

of position and the ground; and he should have put an officer in charge who had more confidence in his plans." With Ewell

occupied at Culp's Hill and General Hill sick, there was no one to accept the role except Lee’s most senior, experienced,

and trusted commander. That left Longstreet with no option but to execute Lee’s plan which he proceeded to carry out

to the best of his ability.

On the balmy afternoon of July 3 and at the time of Pickett's Charge,

it was 87 degrees, which was also the maximum temperature at Gettysburg for the month of July 1863. With battles on July 1-2,

the Gettysburg battlefield was still processing and absorbing the blood of thousands of men and hundreds of horses. In one

last grand assault, also known as Longstreet's Grand Assault, Pickett was about to lead his division through mixed terrain

and into the Union ring of fire.

Longstreet had the responsibility of organizing and deploying over 12,000

men from two different corps, in a line over a mile long and have them maneuver so as to converge on a narrow front of the

Union line. Longstreet escorted Pickett to the crest of Seminary Ridge to show him where to shelter his men, the direction and the point of the attack. Pickett "seemed to appreciate the severity

of the contest he was about to enter, but was quite hopefull of success." Colonel James B. Walton, the Chief of Artillery

of Longstreet’s Corps, was sent for so he could learn the plans and arrange the signal for the start of the cannonade.

Walton and Alexander organized 75 guns from Longstreet’s corps for the opening barrage. Brig. General William N. Pendleton,

the army’s Chief of Artillery, issued orders for Hill’s and for some of Ewell’s artillery to assist in the

cannonade. The batteries of Longstreet, and apparently Hill, "were directed to be pushed forward as the infantry progressed,

protect their flanks, and support their attack closely."

| Pickett's Charge Battlefield Map |

|

| Pickett's Charge Map, by Civil War Trust |

| Col. Alexander |

|

| (LOC) |

The officer responsible for determining the effect of the cannonade, and thus the timing of the assault,

was to be Colonel E. P. Alexander and not James B. Walton. Longstreet justified Alexander’s increased responsibility

by explaining that, in this situation, he considered Alexander as more of an engineer staff officer than a battalion commander.

Longstreet said that Alexander was more familiar with the ground and was an officer of "unusual promptness, sagacity, and

intelligence." At about 11:00 A.M., Alexander reported that the artillery was posted and ready. He was then "ordered to a

point where he could best observe the effect of our fire, and to give notice of the most opportune moment for our attack."

Colonel Birkett D. Fry, commanding Archer’s Brigade of Pettigrew's Division, reported that during the forenoon he observed Lee, Longstreet, and Hill sitting down on a fallen tree near

Spangler’s Woods to examine a map. After the trio remounted, staff officers and couriers issued orders for the coming

assault. Longstreet later reported that Lee rode with him at least twice to see that everything was properly arranged. Longstreet

also told Lee, "that we had been more particular in giving the orders than ever before; that the commanders had been sent

for, and the point of attack had been carefully designated, and that the commanders had been directed to communicate to their

subordinates, and through them to every soldier in the command, the work that was before them, so that they should nerve themselves

for the attack, and fully understand it."

Pickett's Division had remained at Chambersburg to guard army supplies when

Longstreet's Corps left for Gettysburg on June 30. It was not until 2:00 A.M. on July 2, that Pickett received orders to proceed

eastward. The head of the division arrived in the area of Marsh Creek, on the Chambersburg Pike three miles west of Gettysburg,

on or about 2:00 P.M. Pickett reported directly to Longstreet two hours later, about the time of Hood’s opening attack

that day, and Col. Walter Harrison, Pickett’s Chief of Staff, reported the division's arrival to Lee. Harrison reported

that Lee stated that Pickett’s men would not be needed that afternoon and that, "I will send him word when I want him."

Harrison’s account of Lee’s remarks may have made General Longstreet believe that Pickett would be moving under

Lee’s orders and not his. Considering Longstreet’s continued debate with Lee over strategy and any uncertainties

about his or Pickett's role, orders should have been clarified directly with Lee. Failure to get such clarification was uncharacteristic

of Longstreet and could be seen by some as bordering on petulance or irresponsibility. Lee also should have made certain that

his orders, however transmitted, were clear and concise. (Baron Jomini, whose writings Lee would have been familiar with,

observed that "Inaccurate transmission of orders... may interfere with the simultaneous entering into action of the different

parts.")

Pickett’s Division had left its bivouac at Marsh Creek at about 3:30

A.M., and was deployed along Seminary Ridge by 7:00 A.M. As Pickett’s brigades were moving into position, it was discovered

that Brig. Gen. Richard B. Garnett’s Brigade would overlap part of Pettigrew’s line and prevent Brig. General Lewis A. Armistead from continuing the line of Garnett’s Brigade. Colonel Walter Harrison, not finding Pickett, saw Lee and Longstreet

on top of the ridge in front making a "close reconnaissance." Harrison needed to find out if Armistead should hold his position

or push out. He found Longstreet in "anything but a pleasant humor at the prospect of ‘over the hill." When Harrison

asked about Armistead, Longstreet "snorted out, ‘General Pickett will attend to that, sir.’" Longstreet, then

suspecting that he may have hurt Harrison’s feelings, added that Armistead could stay where he was and could make up

the distance when the advance started. There was also minor confusion in Pettigrew's ranks. Capt. Louis G. Young, aide-de-camp

to Pettigrew, wrote that the division had been directed by Longstreet "to form in rear of Pickett’s Division and support

his advance," but that the order "was countermanded almost as soon as given, and General Pettigrew was instructed to advance

upon the same line with Pickett, a portion of Pender’s Division acting as supports."

Harrison and Young seem to imply that Pickett’s Division was originally

to deploy into a division front with all three brigades (Kemper, Garnett, and Armistead) in one line and with Pettigrew

as a support. The division was eventually deployed into two lines with Kemper's and Garnett's commands in front and Armistead

in a second line. Longstreet, probably through Hill, arranged Pettigrew and Trimble into three lines. Pettigrew’s regiments

appear to have been deployed into division columns thus forming two battle lines with Trimble’s two brigades in support.

This was probably done to add more weight to the center of the attacking column. Wilcox was ordered to move on the right flank

of Pickett, "to protect it from any force that the enemy might attempt to move against it."

Longstreet appeared to have worked closely with Hill in arranging Hill’s

troops. Although some historians claimed that Longstreet and Hill did not get along, Longstreet’s staff denied this.

After the Seven Days Campaign in 1862, reports in the Richmond papers (for which Longstreet blamed Hill) gave credit to Hill’s

Division at the expense of Longstreet’s Division. This dispute caused Hill to ask for a transfer to T. J. Jackson’s

command. The relationship between Longstreet and Hill was strained for only a short time "and they were warm friends until

the day of General Hill’s death." Realistically, there was no time for jealousies between the two officers while the

preparations were made for the attack. Longstreet remembered that after the troops were in position, Lee accompanied him as

they again rode over the field, "so that there was really no room for misconstruction or misunderstanding of his wishes."

Longstreet, "rode once or twice along the ground between Pickett and the Federals, examining the positions and studying the

matter over in all its phases so far as we could anticipate." On occasion, the corps commander, "looked after Pickett, and

made us give him things very fully; indeed, sometimes stay with him to make sure he did not get astray."

Longstreet wrote that Pickett, "who had been charged with the duty of arranging

the lines behind" the artillery, reported that the troops "were in order and on the most sheltered ground." Longstreet also

stated that Pickett had been ordered to form his line "so that the center of the assaulting column would arrive at the salient

of the enemy's position." Pickett was to be the guide for the attacking column and was to "attack the line of the enemy’s

defenses." Pettigrew was to move on the same line as Pickett and "was to assault the salient at the same moment." The only change to these orders,

of which Longstreet may not have been aware, was that at the start of the advance, Fry’s Brigade in Pettigrew’s

column was the brigade of direction. This arrangement was made by Pickett, Garnett, and Fry prior to the cannonade.

Longstreet later confessed that he was never so depressed as on July 3. He

felt his men were to be sacrificed and that he "should have to order them to make a hopeless charge." Despite his depressed

feelings, he appears to have maintained his professional objectivity and not to have transmitted his misgivings to any of

the field commanders, with the possible exception of Alexander. Longstreet's noontime note to Alexander stated, "if the artillery

fire does not have the effect to drive off the enemy or greatly demoralize him, so as to make our effort pretty certain, I

would prefer that you should not advise Gen Pickett to make the charge."

Longstreet, "being unwilling to trust myself with the entire responsibility,"

appears to have come close to abnegating his duty by placing the responsibility for ordering the attack on the shoulders of

a 26-year old lieutenant colonel. Alexander, who also wanted to avoid the responsibility, began to see "overwhelming reasons

against the assault." Alexander discussed these points with Brig. General A. R. Wright as he wrote a reply. Alexander, who

did not keep a copy of his reply, stated, in effect, that he would only be able to judge the effect of his fire by the enemy’s

return fire and if there was any alternative to the attack "it should be carefully considered." This note seems to have brought

Longstreet back to his sense of duty. He replied that it was the intention to advance the infantry if the artillery could

drive off the enemy. When that happened Alexander was to advise Pickett and advance such artillery as he could to aid the

attack. Alexander still felt uncomfortable. Wright informed Alexander "that the difficulty was not so much in reaching

Cemetery Hill, or taking it - that his brigade had carried it the afternoon before - but that the trouble was to hold it,

for the whole Federal army was massed in a sort of horse-shoe shape and could rapidly reinforce the point to any extent."

Alexander next visited Pickett "who seemed to feel very sanguine of success in the charge, and was only congratulating himself

on the opportunity." In his last message to Longstreet, Alexander said that when "our artillery fire is at its best, I will

advise Gen Pickett to advance."

After receiving this last message, at about 12:40 P.M. and having done everything

he could to get the men ready, Longstreet took a nap. It could not have been a very long nap, for at about 1:00 p.m. the following

message was sent to Col. Walton: "Let the batteries open. Order great care and precision in firing. If the batteries at the

Peach Orchard cannot be used against the point we intend attacking let them open on the enemy on the Rocky Hill."

Shortly after the Confederate batteries opened at 1:00 P.M., the Union artillery

responded. Longstreet, perhaps to help steady his men while under this fire, started to ride along Pickett’s front.

Captain John Holmes Smith, 11th Virginia Infantry in Kemper’s Brigade, observed Longstreet riding along "as

quiet as an old farmer riding over his plantation on a Sunday morning, and looked neither to the right or left." General Kemper

related that Longstreet, "sat his large charger with a magnificent grace and composure I never before beheld. This bearing

was to me the grandest moral spectacle of the war. I expected to see him fall every instant. Still he moved on, slowly and

majestically, with an inspiriting confidence, composure, self-possession and repressed power, in every movement and look that

fascinated me." Concerned for his commander's safety, Kemper warned "this is a terrible place" and not "the very safest place

about here." Longstreet replied that he was greatly distressed by the Union fire, but that "we are hurting the enemy badly,

and will charge him presently." As he rode off, Longstreet seemed to Kemper, "as grand as Arthur to Guinevere, when he lead

his hosts ‘far down to that great battle in the west.’"

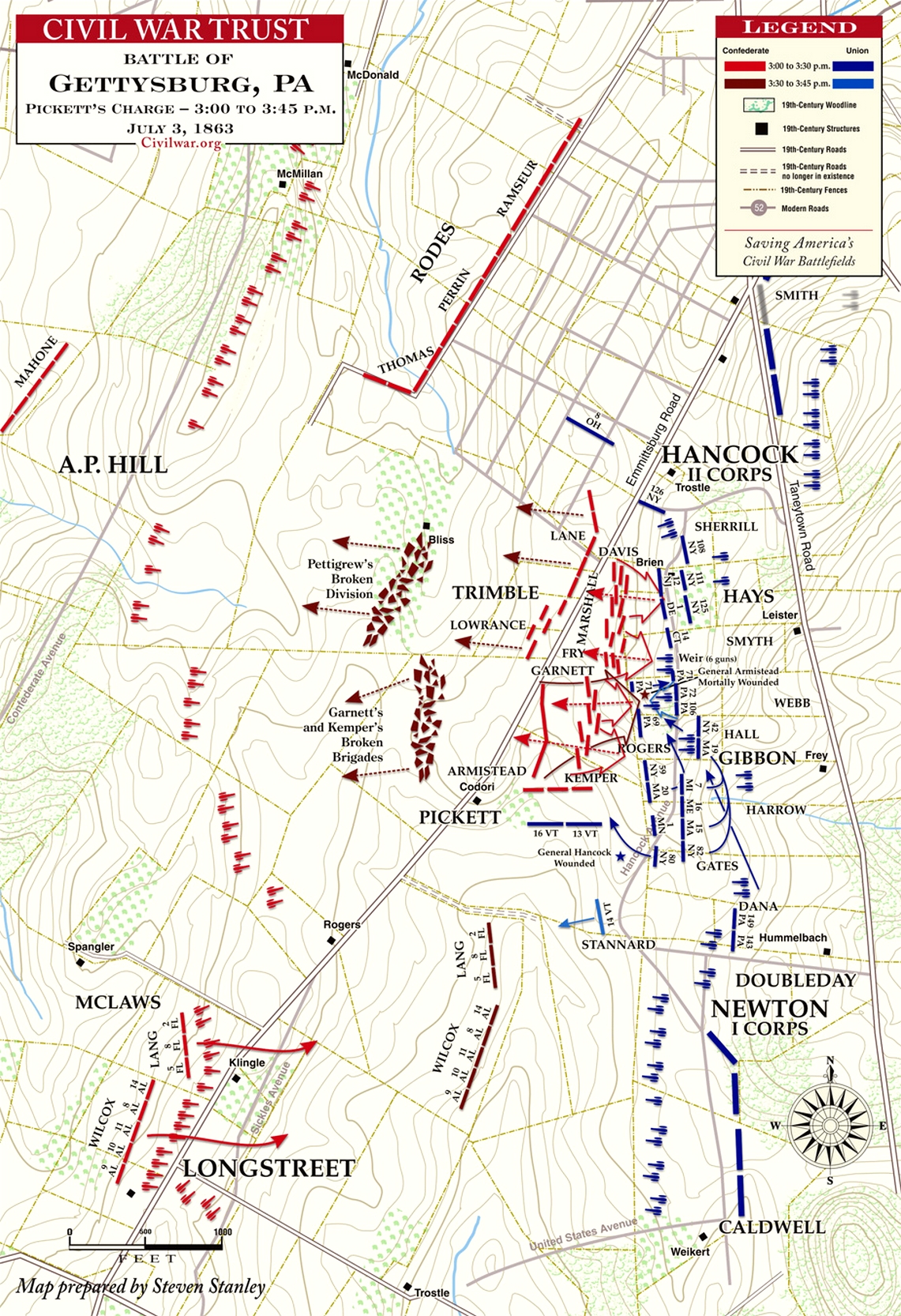

| Pickett's Charge Map, July 3, 1863 |

|

| Longstreet's Grand Assault, more popularly known as Pickett's Charge, by Civil War Trust |

| A battery under fire |

|

| by Edwin Forbes |

Longstreet rode to Major James Dearing’s artillery positions near the Rogers’ House along the

Emmitsburg Road to observe the effect of the cannonade at close range. It was at this point that Longstreet decided that if

the attack had any chance of success it had to be made soon, passing on orders for the batteries to refill their ammunition

chests and to follow the infantry advance. Longstreet next rode to Alexander’s position and finding that Alexander had

already advised Pickett to advance, he reported that "I gave the order to General Pickett to advance to the assault." (Although

this is a very positive statement, every other account, including later ones by Longstreet, paints a slightly different picture.

After talking with Alexander, it appears that Longstreet rode to Spangler's Woods to meet with Pickett. When Pickett asked permission to advance, Longstreet was so overcome with the certainty

of what lay ahead for his men that he could not speak and could only bow his approval.)

After issuing the attack order, Longstreet rode back to Alexander’s

position and found "that our supply of ammunition was so short that the batteries could not reopen. The order for this attack,

which I could not favor under better auspices, would have been revoked had I felt that I had that privilege." Alexander confirmed

that Longstreet wanted him to stop Pickett until the ammunition had been replenished. When told that this, "would involve

sufficient delay for the enemy to recover himself, and moreover, that the supply of ammunition in the ordnance trains was

not sufficient to support a fifteen minutes fire or to either renew our present effort, or attempt another, he recalled the

order and allowed the division, then just approaching... to advance, saying, however, to me, that he dreaded the result and

only ordered it in obedience to the wishes of the Commanding General." Alexander felt that Longstreet would have stopped the

charge with "a word of concurrence from me," though Longstreet knew the only person who could stop the attack was Lee as he

later confirmed:

|

"When your chief is away, you have a right to exercise discretion; but

if he sees everything that you see, you have no right to disregard his positive and repeated orders. I never exercised discretion

after discussing with General Lee the points of his orders, and, when, after discussion, he ordered the execution of his policy.

I had offered my objections to Pickett’s battle and had been overruled, and I was in the immediate presence of the commanding

general when the order was given for Pickett to advance." |

Apparently no one inquired about the quantity of artillery ammunition. General

Pendleton, the army’s Chief of Artillery, might have been able to supply an approximate answer after checking with the

various corps chiefs of artillery and taking a quick inventory of the army’s supply train. Pendleton did report that

Longstreet’s ordnance train had been moved further to the rear from "the convenient locality I had assigned it," necessitating

a longer time in refilling the caissons. He also noted that the "train itself was very limited, so that its stock was soon

exhausted, rendering requisite demand upon the reserve train, further off. The whole amount was thus being rapidly reduced."

Alexander did imply the shortage in his first note to Longstreet stating that "ammunition is already very low. It will take

it all to try this attack, and we will have nothing left for a new one." Dearing reported that just before the infantry advanced

"my ammunition became completely exhausted, excepting a few rounds in my rifled guns." He, too, had sent his caissons back

for a fresh supply "an hour and a half before" but they were unable to get any. If Longstreet had known of this situation

earlier he would have had his best argument against the attack.

The infantry line of Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble began their advance and

Union artillery immediately responded. Longstreet, with "his soldierly eye watched every feature of it. He neglected nothing

that could help it," later observing that the "advance was made in a very handsome style, all the troops keeping their lines

accurately, and taking the fire of the batteries with great coolness and deliberation." Seeing a threat to Pettigrew’s

left flank, Longstreet sent Major Osmun Latrobe of his staff to warn Trimble. Latrobe’s horse was shot from under him

and by the time he delivered the message Trimble had already detached two regiments from Lane’s Brigade to protect the

left. Longstreet then sent Moxley Sorrel to warn Pickett about a threat to his right. In the confusion, Sorrel failed to find

Pickett but did find Armistead and Garnett on the way to the front. Sorrel also had his horse shot from under him when a shell

burst took off both hind legs.

Wilcox and Lang did not advance at the same time as Pickett and the reason

is unclear. Apparently Wilcox misunderstood his role, and later reported that he did not receive any orders to support Pickett

until about 20 or 30 minutes after the advance started. At that time "three staff officers in quick succession (one from the

major-general commanding division) gave me orders to advance to the support of Pickett’s division." Lang reported that

Pickett’s Division had already fallen back when he and Wilcox began their advance. Since the advance of Wilcox and Lang

appears to have been a case of too little too late, historians have asked why they were ordered forward or why the order was

not rescinded. There is no clear answer. Longstreet’s attention may have been focused on Pickett’s Division and

he was not completely aware of Wilcox’s move. What was clear to Longstreet was that the attack had failed. Longstreet

believed the left of the column was staggered by artillery fire and sent word to Anderson to move forward "to support and

assist" Pettigrew and Trimble. Anderson was about to comply when Longstreet countermanded his orders, adding "that it was

useless, and would only involve unnecessary loss, the assault having failed." Instead, Anderson placed his men in line "to

afford a rallying point to those retiring." Longstreet directed his staff to assist Wright, "with all the officers... to rally

and collect the scattered troops behind Anderson’s division."

Longstreet feared a possible Union counter-attack and rode to the front of

the batteries along Alexander’s line, "to reconnoiter and superintend their operations," hoping his presence "would

impress upon every one of them the necessity of holding the ground to the last extremity." Observing the general, Colonel

Fremantle was impressed: "(Few) could have been more calm or self-possessed than General Longstreet under these trying circumstances....I

could now thoroughly appreciate the term bulldog, which I had heard applied to him by the soldiers. Difficulties seem to make

no other impression upon him than to make him a little more savage." Fremantle also remembered Longstreet meeting with another

general, possibly Wilcox, who informed him that "he was unable to bring his men up again." Longstreet shot back, ‘Very

well; never mind then, General; just let them remain where they are: the enemy’s going to advance, and will spare you

the trouble.’" Soon after, Longstreet asked for something to drink and Fremantle offered him some rum from a silver

flask, telling the general to keep the flask "in remembrance of the occasion."

What were General Rodes, Colonel Perrin, and General Thomas, stationed with

their troops in Long Lane, doing during the charge? These were some of the troops that Lee’s staff officers later said

were to have taken part in the assault. Rodes reported that when the "favorable opportunity seemed to me close at hand," he

sent word to Ewell, not Longstreet, "that in a few moments I should attack." When Rodes realized that the troops on his immediate

right, Perrin and Thomas, had not "made any advance or showed any preparation" it was announced and apparent to Rodes that

the attack had failed. Perrin did not report on the attack specifically, but did speak of heavy skirmish fighting. He also

stated that at "one time the enemy poured down a heavy torrent of light troops," probably a strong skirmish line, necessitating

the deployment of the 14th South Carolina to charge the enemy. Although Thomas reported that his brigade made no

movement, the 35th Georgia did advance, perhaps in support of the 14th South Carolina or in support

of Pettigrew’s and Trimble’s withdrawal.

As the attack drew to its tragic conclusion, Longstreet sent Moxley Sorrel

to order McLaws and Law to retire their commands to Warfield Ridge, the original attack positions of July 2. McLaws argued

that there was no necessity for the order and that it was important to hold the ground that had already been won. When Sorrel

explained that the order left no room for discretion, McLaws began to pull his brigades back to Warfield Ridge. After reoccupying

the ridge line, Sorrel returned and asked McLaws if he could reoccupy the position he had just left. When asked for an explanation,

Sorrel said that "General Longstreet had forgotten that he had ordered it, and now disapproved the withdrawal." These orders

may indicate some confusion on Longstreet’s part which followed the end of Pickett's Charge and the general's attempt

to consolidate his battered corps. Sorrel, himself, never wrote of this incident. Longstreet did report that after nightfall

his line "was withdrawn to the Gettysburg road on the right, the left uniting with Lt. General A. P. Hill’s right."

The next evening, Lee and Longstreet led the army on a retreat from Gettysburg and onto the road that would eventually take

them to Appomattox Court House.

In the immediate aftermath of the Gettysburg Campaign, questions arose over

the conduct of the battle and critics found General Longstreet's actions to be questionable, especially in his lack of enthusiasm

in carrying out orders. Longstreet defended his actions maintaining that, "we were not to deliver an offensive battle, but

so maneuver that the enemy should be forced to attack us - or, to repeat, that our campaign should be one of offensive strategy,

but defensive tactics." Longstreet desired to swing south of Gettysburg and find good defensive positions, but Lee was determined

to drive the Union army away from Gettysburg. As Lee's subordinate, Longstreet well knew his obligations to the army commander

as he expressed in a private letter to his uncle, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, written July 24, 1863:

|

"General Lee chose the plan adopted, and he is the person appointed to

chose and to order. I consider it a part of my duty to express my views to the commanding general. If he approves and adopts

them it is well; if he does not, it is my duty to adopt his views, and to execute his orders as faithfully as if they were

my own." |

While clearly not approving of Lee’s July 3rd attack, Longstreet did

everything he could, both before and during the charge, to ensure its success. Moxley Sorrel supported his commander: "(Longstreet)

did not want to fight on the ground or on the plan adopted by the General-in-Chief. As Longstreet was not to be made willing

and Lee refused to change or could not change, the former failed to conceal some anger. There was apparent apathy in his movements

(lacking) the fire... of his usual bearing on the battlefield."

General Longstreet's military career ended with the demise of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House in 1865. As the years passed from that event and America entered into the age of Reconstruction, the debate began as to why the Confederates lost at Gettysburg. This debate, at times an acrimonious one, naturally centered on

the actions and personality of James Longstreet whose performance throughout the Civil War, and particularly at Gettysburg,

came under increasing scrutiny and criticism. Much of this was brought about by partisan politics and the writings of Virginia

authors who championed the myth of The Lost Cause. Unlike some ex-Confederates, Longstreet did not wish to dwell on

the past. He believed it was time to heal old wounds and look to the future. He thought this might entail ex-Confederates

joining the Republican Party in order to control the Negro vote and the South’s future. He discussed this idea with

other ex-Confederates, such as P. G. T. Beauregard, and his uncle August Baldwin Longstreet. Both advised against making his

views public, but after passage of the Reconstruction Acts in 1867, Longstreet wrote:

|

"My politics is to save the little that is left us, and to go to work to

improve that little as best we may. I believe that the course that some politicians have pursued, tends to increase our humiliation

and distress, and leads us to greater trouble, until we finally shall have confiscation and expatriation. Since the negro

has been given the privilege of voting, it is all important that we should exercise such influence over that vote, as to prevent

it being injurious to us, 'we can only do that as Republicans. As there is no principle at issue now that should keep us from

the Republican party, it seems to me that our duty to ourselves', to all our friends requires that our party South should

seek an alliance with the Republican party..." |

On October 12, 1870, Robert E. Lee passed away. The man who had assumed full

responsibility for the defeat at Gettysburg was to be very rapidly raised to the pinnacle of Southern heroes who embodied

the myth of the Lost Cause. In order to raise Lee, however, it became necessary to find a scapegoat for the loss at Gettysburg.

Longstreet became the perfect choice due to his political apostasy, and comments found in William Swinton’s book, History

of the Army of the Potomac, that suggested Longstreet was disloyal to Lee. This was perfect fuel for two of the leaders

of the anti-Longstreet crusade, Jubal Early and William N. Pendleton. Early's military career was just as controversial as

his antagonist. He had issued the order to burn Chambersburg in 1864 and then had been fired by Lee after the Shenandoah Valley

Campaign that year. Early became president of the Southern Historical Society and led the movement to elevate Lee. Pendleton,

who had come to Longstreet just prior to Appomattox with the suggestion that he advise Lee to surrender (a suggestion strongly

rejected by Longstreet), may also have had some personal motives behind his attacks. Both of these men, for various reasons,

decided that they had to defend Lee’s reputation and champion what has become known as the "Lost Cause". Part of this

"myth" of the Lost Cause holds that by losing Gettysburg the South lost its chance at independence. In turn, Longstreet was

responsible for the loss at Gettysburg, and he alone cost the South its independence.

Pendleton's writings were particularly vicious, charging that Longstreet failed

to attack at dawn on the morning of July 2 as ordered by Lee. He also questioned Longstreet’s conduct throughout the

battle and his loyalty to Lee. Pendleton’s own official report, however, and the testimony of Lee’s staff officers,

clearly shows that Lee never issued a "dawn attack" order. T. J. Goree, and other Longstreet supporters, felt that Pendleton

was presuming upon Longstreet’s unpopularity to make these charges. Goree added that it was, "preposterous and absurd,

and must to every soldier of the Army of Virginia(,) the idea of such an old granny as Pendleton presuming to give

a lecture or knowing anything about the battle of Gettysburg--Although nominally Chief of Artillery, yet he

was in the actual capacity of Ordnance Officer, and, as I believe, miles in the rear. I know that I did not see him on the

field during the battle."

In a letter to Jefferson Davis, Jubal Early claimed that he had, through his

articles in the Southern Historical Society Papers, "fully demonstrated the falsehood of many of Longstreet’s

statements, and the absurdity of his pretensions and criticisms." Early also wrote that articles written by Longstreet for

Century Magazine, "has demonstrated his want of sense as well as his utter disregard for the truth, as he had before

shown his utter want of principle by his political course."

Others joined the fray, especially on the hot debate of the general's actions

during "Pickett's Charge". Feeling that Longstreet’s articles had unjustly criticized Lee’s performance, some

of Lee’s former staff officers authored their own accounts of what they thought happened on July 3. The most notable

was Walter Taylor's memoir, Four Years with General Lee. Brig. General Benjamin G. Humphreys, who had assumed command

of Barksdale’s Brigade at Gettysburg, felt compelled to refute Taylor’s charges. In the margins of his copy of

Taylor’s book, Humphreys questioned the statement that Lee had ordered Longstreet to order McLaws and Hood to support

Pickett, who gave the orders and why they apparently were not transmitted to Longstreet. He also questioned Taylor’s

assertion that "it is not apparent" how McLaws and Hood were needed to protect Longstreet’s flank. "Not apparent

to whom?", Humphreys wrote. "To General Lee? Did Lee ever say so? 'Not apparent' to whom? To W. H. Taylor? Wonderful, with

40,000 watchful, vigilant Yankees on Round Top, not over 1 mile off and overlooking every movement of McLaws and Hood, 'yet

it is not apparent' to W. H. Taylor- 'how they were necessary to defend his flank and rear.'"

| Gettysburg Battlefield Map |

|

| Battle of Gettysburg Map |

| General Longstreet in 1895 |

|

| (Library of Congress) |

Longstreet found support in other quarters. For a variety of reasons, the survivors of Pickett’s Division

showed little or no interest in elevating Lee at the expense of Longstreet. In 1874, James Kemper won the governorship of

Virginia on a Conservative ticket. He, like Longstreet and Pickett, believed that it would be best for the South to look to

the future instead of dwelling on the past. But hard-core Lost Cause advocates, who led the anti-Longstreet forces and remained

loyal Democrats, saw Longstreet, Kemper, and Pickett as traitors to their Southern heritage. Throughout the 1870’s and

1880’s, the editorial board of the Southern Historical Society Papers, essentially controlled by Jubal Early, kept most

accounts by Pickett’s men out of their publication unless it could somehow be used to attack Longstreet. Pickett’s

men never blamed Longstreet for what happened on July 3 and refused to join the anti-Longstreet crusade. But the power in

the pens of Early, Pendleton, and others was successful in making James Longstreet one of the most hated men in the South

to the extent that he was formally snubbed from ceremonies and memorials honoring the heroes of the Confederacy.

But the men who served under the general were the ones who ultimately came

to his support. In 1890, The Washington Artillery of New Orleans insisted that Longstreet be invited to the unveiling of the

Lee statue in Richmond or they would not attend. The group was prestigious enough to overcome the anti-Longstreet forces and

secure invitations on his behalf. Longstreet remembered:

|

"My carriage attracted more attention I suppose than was expected and we

were sidetracked, but that only made it more unpleasant for the managers. Generals Fitz Lee, (John B.) Gordon, and other grandees

rode along, but little noticed by the troops in line, but as they passed our carriage they broke and crowded about us and

hurried around in such crowds as to block the street, which threatened to break up the procession, and when urged on tried

to take the horses from the carriage, and pull it along with them, and it was all that Latrobe and Cullen could do to urge

them on, and preserve their line of order." |

In 1892, at the third annual meeting of the United Confederate Veterans in

New Orleans, Longstreet was again recognized by the men who had served under his command. "The business was interrupted by

calls for opportunity to come up and shake my hand," the aging general recalled, "and ended by hurrying (John B.) Gordon and

others of the managers from the stand in order to make room for the soldiers to come up and meet me." Clearly, when Longstreet

made these rare appearances, most ex-Confederate soldiers were able to rise above partisan politics and disparaging rhetoric,

and remember the Longstreet who had led them through four years of war. T. J. Goree spoke for most veterans when he wrote

to the general:

|

"With my heart full of gratitude, I often think of you and of many acts

of kindness shown me, and the innumerable marks of esteem and confidence bestowed upon me by you during the four long and

trying years that we were together. Although we may differ in our political opinions, yet I have always given you

credit for honesty and sincerity of purpose, and it has made no difference in my kindly feelings towards you personally, and

I trust that it never will." |

Despite the adulation of his old command, an anti-Longstreet attitude has

prevailed among historians into this century, most notably by Douglas Southall Freeman and Clifford Dowdey. Some writers,

such as Donald B. Sanger, Edwin B. Coddington, William G. Piston, and Carol Reardon, have been more objective in their approach

to the events of July 3 and to Longstreet’s role. While we might normally leave the last word on Longstreet to these

historians, it is more appropriate to give the last word to a veteran of "Pickett's Charge". Speaking to the Buffalo Evening News, during the 75th Anniversary Reunion at Gettysburg, a former officer in Pickett’s

Division remarked:

|

"Longstreet opposed Pickett’s Charge, and the failure shows he was

right.... All these damnable lies about Longstreet make me want to shoulder a musket and fight another war. They originated

in politics and have been told by men not fit to untie his shoestrings. We soldiers on the firing line knew there was no greater

fighter in the whole Confederate army than Longstreet. I am proud that I fought under him here. I know that Longstreet did

not fail Lee at Gettysburg or anywhere else. I’ll defend him as long as I live." |

(Sources and related reading below.)

Recommended

Reading:

General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier (Simon

& Schuster). Description: This isn't the first biography to be written on Confederate General James Longstreet,

but it's the best--and certainly the one that pays the most attention to Longstreet's performance as a military leader. Historian

Jeffry D. Wert aims to rehabilitate Longstreet's reputation, which traditionally has suffered in comparison to those of Robert

E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Some Southern partisans have blamed Longstreet unfairly for the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg; Wert corrects the record. He is not “uncritical”

of Longstreet's record, but he rightly suggests that if Lee had followed Longstreet's advice, the battle's outcome might have

been different. Continued below...

The

facts of history cannot be changed, however, and Wert musters them on these pages to advance a bold claim: "Longstreet, not

Jackson,

was the finest corps commander in the Army of Northern Virginia; in fact, he was arguably the best corps commander in the

conflict on either side." Wert describes his subject as strategically aggressive, but tactically reserved. The bulk of the

book appropriately focuses on the Civil War, but Wert also briefly delves into Longstreet's life before and after it. Most

interestingly, it was framed by a friendship with Ulysses S. Grant, formed at West Point

and continuing into old age. Longstreet even served in the Grant administration--an act that called into question his loyalty

to the Lost Cause, and explains in part why Wert's biography is a welcome antidote to much of what has been written about

this controversial figure.

Advance to:

Recommended

Reading:

James Longstreet: The Man, The Soldier, The Controversy (Hardcover). Description: Few figures from the American Civil

War have generated more controversy than Confederate general James Longstreet. As the senior officer present at Pickett's

Charge, he has been blamed by many, particularly in the South, for the decisive Confederate defeat at Gettysburg. Other scholars have cited his exemplary combat record during the Civil War and

looked to rivals within the Confederate hierarchy or his post-war support for the Northern-based Republican Party as sources

for the criticism leveled at him. Richard L. DiNardo and Albert A. Nofi have assembled some of the top Civil War and Longstreet

scholars to fully examine this still-controversial topic. Continued below...

About the Author: Albert A. Nofi has a Ph.D. in Military History from the

City University of New York and was associate editor for many years of the ground-breaking military journal Strategy and Tactics.

He was a founder of wargaming, the conflict simulation system used both by hobbyists and military planners. Dr. Nofi has written

numerous books and articles on military history and was a news media military commentator during the Persian Gulf War. He

is also the author of The Gettysburg Campaign and The Waterloo Campaign.

Recommended

Reading:

General James Longstreet: the Confederacy's Most Modern General. Description: While many books and writings are available

on the history of Lieutenant General James Longstreet of the Confederate States Army, nearly the entire body of this historiography

marginalizes his accomplishments and is devoted to his falling from grace with the postwar Southern elites. This piece of

historiography aims to look at Longstreet with twenty-first century objectivity, and completely abandons the Lost Cause linked

hatred that many postwar Southern elites had for him and his post war politics. While Longstreet s political incorrectness

was the reason he became ignored, politics is completely irrelevant to the student of warfare looking to garner lessons from

Longstreet s battles and campaigns. This work will compare the similarities of Longstreet s innovations and operations to

certain aspects of war that became standard in the First and Second World Wars. Continued below...

Interpreting

Longstreet through the comparison of his methods to twentieth century methods shows Longstreet was a very modern general.

Even more important than identifying Longstreet s originality is identifying how his actions greatly added to the changing

complexion of warfare. Some of his innovations were the early origins of prominent facets in twentieth century warfare, and

he clearly established his legacy as a modern innovator as early as 1862. But only now are the postwar negative portrayals

of Longstreet faded enough for him to emerge as the Confederacy s most modern general.

Recommended Reading: Lee's Tarnished Lieutenant: James Longstreet and His

Place in Southern History. Description: William Piston has written a fine, highly readable, and fair-minded but sympathetic

biography of one of the most controversial leaders of the Civil War. While Lee held Longstreet in the highest regard and made

the dependable Longstreet his senior subordinate and commander of his First Corps in the Army of Northern Virginia, the stubborn

South Carolinian, Longstreet, found his reputation tarnished after the war by jealous military rivals who disliked Longstreet's

politics and resented his criticisms of some of Lee's command decisions. As a military biography, this work offers a comprehensive

and balanced treatment of Longstreet's career that effectively demolishes some of the more unfair criticisms of Longstreet

as a commander, and in particular takes apart the myth (that emerged in post-war controversy) that Jackson, not Longstreet,

had been the senior commander in whom Lee had placed his most reliance and trust. Continued below...

Reading

Piston's book will demonstrate why Lee described Longstreet as "my Old War Horse," and why Longstreet was widely regarded

on both sides as one of the very finest -- if not THE finest -- corps commanders of the war. Piston also does a nice job of

disentangling the post-war Gettysburg controversy, which emerged out of polemics over Reconstruction politics and the bickering

among former Confederate generals anxious to rescue their own reputations while putting Robert E. Lee above any criticism.

Lee, of course, was a great commander, but he never pretended to be perfect, and Longstreet, in daring to criticize certain

aspects of Lee's tactical operations, became a threat to a post-war mythology -- the cult of Lee -- that became so important

in building a post-war, solid Democratic South and white supremacist post-Confederate Southern identity. As Piston demonstrates,

the post-war Lost Cause mythology, in deifying the defeated Lee, required a scapegoat, a "Judas", upon whom the blame for

defeat and humiliation could be heaped. As both Jackson and Stuart had been killed during the war, and as most western Confederate

commanders lacked the prominence to serve this function, Longstreet emerged for unreconstructed Confederates as the bete

noir of Southern military history, both for his post-war Republican politics and his criticisms of Lee, his actual war

record and relationship with Lee notwithstanding. And in this post-war Lost Cause narrative, Gettysburg became the critical key or turning point

upon which all else hinged, as though the outcome of a thousand campaigns mobilizing millions of men, fought over five years

across a vast continent, could be reduced to one afternoon on one bloody field in Pennsylvania, or as though (even if that

had been true) Longstreet alone could be blamed for Lee's failure at Gettysburg. It is the politics of Reconstruction and

Longstreet's place in that political struggle that largely shaped what became the dominant Southern narrative about the battle

of Gettysburg,

and the meaning of that defeat in the larger destruction and humiliation of the Confederacy. Piston's treatment of this issue,

and his discussion of the evolution of Lost Cause historiography, is brilliant, and deserves attention not only from those

interested in the Civil War and Reconstruction, but from those interested in the relationship between politics, historical

memory, the historical record, and the writing of history.

Recommended

Reading:

Civil War High Commands (1040 pages) (Hardcover). Description: Based on nearly five decades

of research, this magisterial work is a biographical register and analysis of the people who most directly influenced the

course of the Civil War, its high commanders. Numbering 3,396, they include the presidents and their cabinet members, state

governors, general officers of the Union and Confederate armies (regular, provisional, volunteers,

and militia), and admirals and commodores of the two navies. Civil War High Commands will become a cornerstone

reference work on these personalities and the meaning of their commands, and on the Civil War itself. Continued below...

Errors of fact and interpretation concerning the high commanders are legion in the Civil War literature,

in reference works as well as in narrative accounts. The present work brings together for the first time in one volume the

most reliable facts available, drawn from more than 1,000 sources and including the most recent research. The biographical

entries include complete names, birthplaces, important relatives, education, vocations, publications, military grades, wartime

assignments, wounds, captures, exchanges, paroles, honors, and place of death and interment. In addition to its main component, the biographies, the volume also includes a number of

essays, tables, and synopses designed to clarify previously obscure matters such as the definition of grades and ranks; the

difference between commissions in regular, provisional, volunteer, and militia services; the chronology of military laws and

executive decisions before, during, and after the war; and the geographical breakdown of command structures. The book is illustrated

with 84 new diagrams of all the insignias used throughout the war and with 129 portraits of the most important high commanders.

It is the most comprehensive volume to date...name any Union or Confederate general--and it can be found in here. [T]he

photos alone are worth the purchase. RATED FIVE STARS by americancivilwarhistory.org

Sources: Jeffrey D. Wert, General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial General, Simon

& Schuster, New York, 1993; H.J. Eckenrode, James Longstreet: Lee's War Horse, University of North

Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1936, 1986; Condensed from the 1998 Gettysburg Seminar paper, by Karlton Smith: Gettysburg

National Military Park.

|