|

The High Water Mark

High Water Mark of Gettysburg

| The High Water Mark |

|

| The High Water Mark, aka The Angle |

The High Water Mark

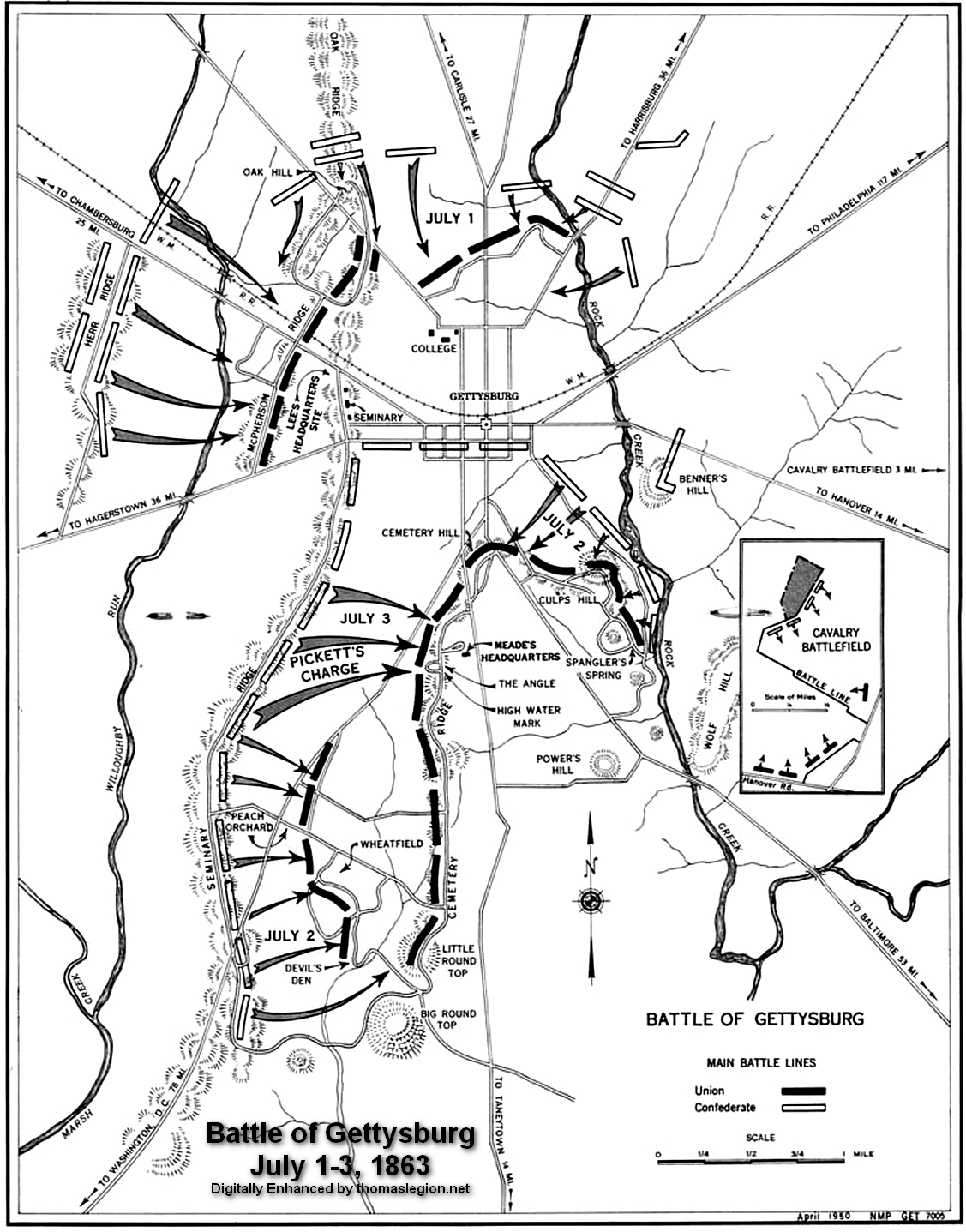

The High Water Mark of the Confederacy refers to an area on Cemetery Ridge

near Gettysburg, marking the farthest point reached by Confederate forces during Pickett's Charge on July 3, 1863. Similar

to the maritime high water mark, the term is a reference to arguably the Confederate Army's best chance of achieving victory

in the war and occurred on the third and final day of fighting at Gettysburg. The last day of fighting at the battle

of Gettysburg consisted of Culp's Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and two cavalry battles: one approximately three miles to

the east, known as East Cavalry Field, and the other southwest of Big Round Top mountain on South Cavalry Field.

This small grove or "copse" of trees had little or no significance prior

to the Battle of Gettysburg, but on July 3, 1863, it was the focal point around which swept vicious hand-to-hand

combat during the climax of "Pickett's Charge". The trees grow within a confined area known as "The Angle", named for the stone fence that bends to the west and then southward to border

the small pasture where the original trees stood. It was behind this stonewall that Union troops were positioned during the

battle. The title of "High Water Mark of the Rebellion" was bestowed upon the copse by John B. Bachelder, the first government

historian of the Gettysburg battlefield, who realized its significance during a visit to the site with a veteran of General Pickett's Division. It was through Bachelder's influence that the "High Water Mark of the

Rebellion Monument" was placed here and dedicated in 1892. The monument lists the commands of both armies that participated

in Pickett's Charge. This grouping of trees marked a Confederate crest of the battle and the war. After Gettysburg, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia would never reach such a high point again.

| High Water Mark and The Angle |

|

| The High Water Mark of Gettysburg |

(Right) Photo of view toward the High Water Mark and the Angle, marked by the single tree at left center,

from the southwest. General Kemper's brigade was in this area and approached the Union line from this direction. Gettysburg

NMP.

Approximately 7,000 Union soldiers of the Second Corps were positioned in

the area of the Angle and adjacent to it, commanded on July 3rd by Brigadier General John Gibbon. Some expressed relief to be over the ordeal of the artillery bombardment

as they gazed at the parade of southern infantry headed toward them. "Beautiful, gloriously beautiful did this vast array

appear in the lovely little valley," observed one soldier. The southerners reached the Emmitsburg Road and began to leap over

the stout fences. "The column pressed on," General Gibbon observed, "coming within musketry range without receiving immediately

our fire, our men envincing a striking disposition to withhold it until it could be delivered with deadly effect."

The Union line suddenly came to life, pouring a dreadful fire of lead into

the southern ranks. Within the acre of ground surrounding the clump of trees was the famed "Philadelphia Brigade", regiments

raised in and around the city of Philadelphia, under the command of Brig. General Alexander Webb. Webb's men sent volley after

volley into the mass of Confederates who pushed onward and, despite the intense fire, reached the stone wall. Congregating

along the wall, Pickett's men intermingled with some from Pettigrew's command and all traded rifle shots across the bare space

of 50 yards between them and some of Webb's men standing on the crest of the ridge. The last of Pickett's brigadiers, General Armistead, pushed his way through the crowd and led a charge over the wall. The fighting was brutal and at one point was hand to hand

in the copse of trees. The last remaining Union batteries used double-shots of canister to blast away groups of southerners

who ventured their way around the Yankees still holding the wall south of the trees. Without reinforcements or support, the

Confederates could not hold the Angle and clump of trees. Those who could retreated to Seminary Ridge leaving behind their dead and wounded.

| Battle of Gettysburg Map |

|

| The High Water Mark and Battle of Gettysburg. NPS. |

| Cushing in the Angle |

|

| Marker to Lt. Alonzo Cushing in the Angle |

(Right) This stone marker to Lt. Cushing was placed in the Angle by his

family, former officers and friends in 1887.

The High Water area is one of the most visited sites on the battlefield and

has been the scene of countless reunions and ceremonies. Veterans of the Philadelphia Brigade and Pickett's Division returned

to this site several times, grasping hands over the same stone wall that

so many had died over during the battle (Last Great Gettysburg Reunion of 1938). The reminders of the men who fought here and those that died live on in the granite and bronze monuments that stands within

the Angle.

While Pickett's men fought for possession of the Angle, the left wing of the

Confederate attacking force was facing a storm of their own from Union troops behind a stone wall stretching from the Angle

to Ziegler's Grove.

The Death of Lt. Cushing

| Lt. Cushing |

|

| (WI Hist. Society) |

Positioned just north of the copse of trees, Battery A, 4th US Artillery was commanded by 22 year-old Lt.

Alonzo Cushing. Born in Wisconsin in 1841, his family had moved to New York where the young Cushing grew up and attended West

Point, graduating in the class of 1861. He had served in staff positions and in command of Battery A in battles prior to Gettysburg,

but it is doubtful he had ever been involved in such intense fighting as he experienced here. Cushing's battery appeared to

be the focus of the Confederate artillery during the cannonade and was nearly destroyed in the furious bombardment. When the

Confederate cannon fire died away, Cushing found himself with only a handful of gunners and two working cannon. Though painfully

wounded by shell fragments, the young lieutenant was unwilling to personally leave the field or retire his shattered battery.

He gained permission from General Webb to move his two guns down to the wall in the Angle where he ordered that extra canister

rounds be piled by each gun. Cushing and his few artillerymen served these guns until the last, the lieutenant himself aiming

and firing one of the double-shotted pieces into the mass of Pickett's Virginians as they closed in on the stone wall. "I

will give them one more shot!", Cushing cried above the din. Seconds later a bullet struck him through the mouth, killing

him instantly, his lifeless body tumbling over the gun trail. The young lieutenant died a hero's death and was later buried

with full honors at his old alma mater, West Point.

Pickett's Brigadiers

| Gen. Armistead |

|

| (Generals in Gray) |

| Gen. Kemper |

|

| (Generals in Gray) |

On the other side of Cushing's marker is a scroll-top granite monument to

General Lewis Armistead, which marks the general location where he was mortally wounded among Cushing's guns on July 3. Erected

and dedicated by friends of the Armistead family in December 1887, it is the first monument dedicated to a Confederate officer

placed at Gettysburg and caused some minor controversy at the time of its placement in the Angle. Prior to the war, Armistead

had been close friends with General Hancock, but the division of the nation caused one to choose the southern cause while

the other remained loyal to the Union. At Gettysburg, the two almost met again. The wounded Armistead told his Union captors

to give his regards to Hancock, also desperately wounded while repulsing the charge. Though his wounds appeared to be non-fatal,

the general died in a Union field hospital on July 5. His body was recovered by friends, who had his remains transported to

Baltimore for burial in the yard of St. Paul's Church.

Of Pickett's three brigadiers, only James Kemper survived the charge. Ignoring orders not to go into the charge on horseback, Kemper rode into the charge

and led his brigade across the Emmitsburg Road south of the Codori Farm buildings. Kemper made his way to a point near the

Union defenses where he was shot by a Union soldier, "so close... that I could clearly recognize his features...". The desperately

wounded general lay on the field until spied by several Union soldiers who ran to him, placed him on a blanket, and began

to carry him into the Union lines. A small group of Confederates raced to Kemper's aid, retrieved him from his Union captors

and carried him to Seminary Ridge where he encountered General Lee. Though his wound appeared to be a mortal one, General

Kemper was taken back to Virginia and eventually recovered. After the war he would serve as the 37th Governor of Virginia

before his death in 1895.

Sources: Gettysburg National Military Park; National Park Service; Library of Congress; Official Records

of the Union and Confederate Armies.

Recommended Reading: Last Chance For Victory: Robert E. Lee And The Gettysburg

Campaign. Description: Long after nearly

fifty thousand soldiers shed their blood there, serious misunderstandings persist about Robert E. Lee's generalship at Gettysburg. What were Lee's choices before, during, and after the battle?

What did he know that caused him to act as he did? Last Chance for Victory addresses these issues by studying Lee's decisions

and the military intelligence he possessed when each was made. Continued below...

Packed with

new information and original research, Last Chance for Victory draws alarming conclusions to complex issues with precision

and clarity. Readers will never look at Robert E. Lee and Gettysburg the same way again.

Recommended Reading:

Pickett's Charge--The Last Attack at Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: Pickett's Charge

is probably the best-known military engagement of the Civil War, widely regarded as the defining moment of the battle of Gettysburg and celebrated as the high-water mark of the Confederacy.

But as Earl Hess notes, the epic stature of Pickett's Charge has grown at the expense of reality, and the facts of the attack

have been obscured or distorted by the legend that surrounds them. With this book, Hess sweeps away the accumulated myths

about Pickett's Charge to provide the definitive history of the engagement. Continued below...

Drawing on

exhaustive research, especially in unpublished personal accounts, he creates a moving narrative of the attack from both Union and Confederate perspectives,

analyzing its planning, execution, aftermath, and legacy. He also examines the history of the units involved, their state

of readiness, how they maneuvered under fire, and what the men who marched in the ranks thought about their participation

in the assault. Ultimately, Hess explains, such an approach reveals Pickett's Charge both as a case study in how soldiers

deal with combat and as a dramatic example of heroism, failure, and fate on the battlefield.

Recommended Reading: The Artillery

of Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: The battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the apex of the Confederacy's final major invasion of the North,

was a devastating defeat that also marked the end of the South's offensive strategy against the North. From this battle until

the end of the war, the Confederate armies largely remained defensive. The Artillery of Gettysburg is a thought-provoking

look at the role of the artillery during the July 1-3, 1863 conflict. Continued below...

During the

Gettysburg

campaign, artillery had already gained the respect in both armies. Used defensively, it could break up attacking formations

and change the outcomes of battle. On the offense, it could soften up enemy positions prior to attack. And even if the results

were not immediately obvious, the psychological effects to strong artillery support could bolster the infantry and discourage

the enemy. Ultimately, infantry and artillery branches became codependent, for the artillery needed infantry support lest

it be decimated by enemy infantry or captured. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had modified its codependent command

system in February 1863. Prior to that, batteries were allocated to brigades, but now they were assigned to each infantry

division, thus decentralizing its command structure and making it more difficult for Gen. Robert E. Lee and his artillery

chief, Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, to control their deployment on the battlefield. The Union Army of the Potomac

had superior artillery capabilities in numerous ways. At Gettysburg,

the Federal artillery had 372 cannons and the Confederates 283. To make matters worse, the Confederate artillery frequently

was hindered by the quality of the fuses, which caused the shells to explode too early, too late, or not at all. When combined

with a command structure that gave Union Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt more direct control--than his Southern counterpart had over

his forces--the Federal army enjoyed a decided advantage in the countryside around Gettysburg. Bradley

M. Gottfried provides insight into how the two armies employed their artillery, how the different kinds of weapons functioned

in battle, and the strategies for using each of them. He shows how artillery affected the “ebb and flow” of battle

for both armies and thus provides a unique way of understanding the strategies of the Federal and Union

commanders.

Recommended

Reading:

Lost Triumph: Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg--And Why It Failed.

Description: A fascinating narrative-and a bold new

thesis in the study of the Civil War-that suggests Robert E. Lee had a heretofore undiscovered strategy at Gettysburg that,

if successful, could have crushed the Union forces and changed the outcome of the war. The Battle of Gettysburg is the pivotal

moment when the Union forces repelled perhaps America's greatest commander-the

brilliant Robert E. Lee, who had already thrashed a long line of Federal opponents-just as he was poised at the back door

of Washington, D.C. It is

the moment in which the fortunes of Lee, Lincoln, the Confederacy, and the Union

hung precariously in the balance. Continued

below...

Conventional

wisdom has held to date, almost without exception, that on the third day of the battle, Lee made one profoundly wrong decision.

But how do we reconcile Lee the high-risk warrior with Lee the general who launched "Pickett's Charge," employing only a fifth

of his total forces, across an open field, up a hill, against the heart of the Union defenses? Most history books have reported

that Lee just had one very bad day. But there is much more to the story, which Tom Carhart addresses for the first time. With

meticulous detail and startling clarity, Carhart revisits the historic battles Lee taught at West Point and believed were

the essential lessons in the art of war-the victories of Napoleon at Austerlitz, Frederick the Great at Leuthen, and Hannibal

at Cannae-and reveals what they can tell us about Lee's real strategy. What Carhart finds will thrill all students of history:

Lee's plan for an electrifying rear assault by Jeb Stuart that, combined with the frontal assault, could have broken the Union

forces in half. Only in the final hours of the battle was the attack reversed through the daring of an unproven young general-George

Armstrong Custer. About the Author: Tom Carhart has been a lawyer and a historian for the Department of the Army in Washington, D.C. He is

a graduate of West Point, a decorated Vietnam veteran, and has earned a

Ph.D. in American and military history from Princeton University. He is the author of four books of military history and teaches at Mary Washington College

near his home in the Washington, D.C.

area.

Recommended Reading:

ONE CONTINUOUS FIGHT: The Retreat from Gettysburg and

the Pursuit of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863 (Hardcover) (June

2008). Description: The titanic three-day

battle of Gettysburg left 50,000 casualties in its wake, a

battered Southern army far from its base of supplies, and a rich historiographic legacy. Thousands of books and articles cover

nearly every aspect of the battle, but not a single volume focuses on the military aspects of the monumentally important movements

of the armies to and across the Potomac River. One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, July

4-14, 1863 is the first detailed military history of Lee's retreat and the Union effort to catch and destroy the wounded Army

of Northern Virginia. Against steep odds and encumbered with thousands of casualties, Confederate commander Robert E. Lee's

post-battle task was to successfully withdraw his army across the Potomac River. Union commander George G. Meade's equally

difficult assignment was to intercept the effort and destroy his enemy. The responsibility for defending the exposed Southern

columns belonged to cavalry chieftain James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart. If Stuart fumbled his famous ride north to Gettysburg, his generalship during the retreat more than redeemed his

flagging reputation. The ten days of retreat triggered nearly two dozen skirmishes and major engagements, including fighting

at Granite Hill, Monterey Pass, Hagerstown, Williamsport, Funkstown,

Boonsboro, and Falling Waters. Continued

below...

President Abraham

Lincoln was thankful for the early July battlefield victory, but disappointed that General Meade was unable to surround and

crush the Confederates before they found safety on the far side of the Potomac. Exactly what Meade did to try to intercept the fleeing Confederates, and how the

Southerners managed to defend their army and ponderous 17-mile long wagon train of wounded until crossing into western Virginia on the early morning of July 14, is the subject of this study.

One Continuous Fight draws upon a massive array of documents, letters, diaries, newspaper accounts, and published primary

and secondary sources. These long-ignored foundational sources allow the authors, each widely known for their expertise in

Civil War cavalry operations, to describe carefully each engagement. The result is a rich and comprehensive study loaded with

incisive tactical commentary, new perspectives on the strategic role of the Southern and Northern cavalry, and fresh insights

on every engagement, large and small, fought during the retreat. The retreat from Gettysburg

was so punctuated with fighting that a soldier felt compelled to describe it as "One Continuous Fight." Until now, few students

fully realized the accuracy of that description. Complimented with 18 original maps, dozens of photos, and a complete driving

tour with GPS coordinates of the entire retreat, One Continuous Fight is an essential book for every student of the American

Civil War in general, and for the student of Gettysburg in

particular. About the Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg has written widely on Civil War cavalry operations. His books include Glory

Enough for All (2002), The Union Cavalry Comes of Age (2003), and The Battle of Monroe's Crossroads and the Civil War's Final

Campaign (2005). He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

J. David Petruzzi is the author of several magazine articles on Eastern Theater cavalry operations, conducts tours of cavalry

sites of the Gettysburg Campaign, and is the author of the popular "Buford's Boys." A long time student of the Gettysburg

Campaign, Michael Nugent is a retired US Army Armored Cavalry Officer and the descendant of a Civil War Cavalry soldier. He

has previously written for several military publications. Nugent lives in Wells, Maine.

Recommended Reading:

General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse. Review:

You cannot say that University of North

Carolina professor Glatthaar (Partners in Command) did not do his homework in this massive examination

of the Civil War–era lives of the men in Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Glatthaar spent nearly 20 years

examining and ordering primary source material to ferret out why Lee's men fought, how they lived during the war, how they

came close to winning, and why they lost. Glatthaar marshals convincing evidence to challenge the often-expressed notion that

the war in the South was a rich man's war and a poor man's fight and that support for slavery was concentrated among the Southern

upper class. Continued below...

Lee's army

included the rich, poor and middle-class, according to the author, who contends that there was broad support for the war in

all economic strata of Confederate society. He also challenges the myth that because Union forces outnumbered and materially

outmatched the Confederates, the rebel cause was lost, and articulates Lee and his army's acumen and achievements in the face

of this overwhelming opposition. This well-written work provides much food for thought for all Civil War buffs.

Recommended Reading: Retreat from Gettysburg:

Lee, Logistics, and the Pennsylvania Campaign (Civil War America) (Hardcover). Description: In a groundbreaking, comprehensive history of the Army of Northern Virginia's retreat

from Gettysburg in July 1863, Kent Masterson Brown draws on

previously unused materials to chronicle the massive effort of General Robert E. Lee and his command as they sought to expeditiously

move people, equipment, and scavenged supplies through hostile territory and plan the army's next moves. More than fifty-seven

miles of wagon and ambulance trains and tens of thousands of livestock accompanied the army back to Virginia. Continued

below...

The movement

of supplies and troops over the challenging terrain of mountain passes and in the adverse conditions of driving rain and muddy

quagmires is described in depth, as are General George G. Meade's attempts to attack the trains along the South Mountain range and at Hagerstown and Williamsport, Maryland. Lee's deliberate pace, skillful

use of terrain, and constant positioning of the army behind defenses so as to invite attack caused Union forces to delay their

own movements at critical times. Brown concludes that even though the battle of Gettysburg

was a defeat for the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee's successful retreat maintained the balance of power in the eastern theater

and left his army with enough forage, stores, and fresh meat to ensure its continued existence as an effective force.

|