|

The High Water Mark and The Angle

of Gettysburg

The High Water Mark of Gettysburg The Angle Battle of Gettysburg Pickett's Charge History,

Results, Cemetery Ridge, Cemetery Hill, Seminary Ridge, General George Pickett, Pickett's Division Details

The High Water Mark : The Angle of Gettysburg

History

The High Water Mark of the Confederacy refers to an

area on Cemetery Ridge near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, marking the farthest point reached by Confederate forces during Pickett's

Charge on July 3, 1863. Similar to a maritime high water mark, the term is a reference to arguably the Confederate Army's

best chance of achieving victory in the war. The line of advance was east of "The Angle" stone wall at various distances

and occurred on the third and final day of fighting at Gettysburg. The

third day of fighting at the battle of Gettysburg consisted of Culp's Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and two cavalry

battles: one approximately three miles to the east, known as East Cavalry Field, and the other southwest of Big Round

Top mountain on South Cavalry Field.

| The High Water Mark of Gettysburg in 1903. |

|

| The Copse of Trees was known as The Angle during Pickett's Charge. Library of Congress. |

(Above) Copse of Trees in 1903. The Copse of Trees, known as The Angle during

Pickett's Charge on July 3, 1863, became synonymous with the High Water Mark of the American Civil War. Courtesy

Library of Congress.

Within the acre of ground surrounding the clump of trees was the famed

"Philadelphia Brigade" composed of regiments raised in and around the city of Philadelphia, under the command of Brig. General

Alexander Webb. A West Point graduate and former instructor at the school, Webb's primary war experience had been as

a staff officer. He had been assigned to command the brigade after the former commander was placed under arrest while on the

march north, and was still unfamiliar with many of its officers and men. These veteran Philadelphians had seen nothing to

equal the mass of gray-clad humanity charging toward them from the Emmitsburg Road. From behind the low stone wall that still

frames the Angle, Webb's men rose and delivered a blast of musketry into the faces of Pickett's men. Private Anthony McDermott of the 69th Pennsylvania saw, "Our first round was fired with deliberation and simultaneously,

and threw their front line into confusion, from which they quickly rallied and opened their fire upon us." As if leaning into

a windstorm, the Confederates forged ahead, driving toward the Angle. Hundreds more fell from the Union volleys while those

in the rear ranks pushed forward. Southerners returned the fire, loading and aiming while they trotted up the slope toward

the wall. Lt. Cushing's last two guns blasted canister into the solid mass until Cushing was killed and the guns abandoned.

And somewhere in the crowd was General Garnett, still on horseback and encouraging his men forward.

| Battle of Gettysburg: The High Water Mark |

|

| (Gettysburg NMP) |

(Right) "The Battle of Gettysburg", painted in 1884 by French artist Paul Dominic Philippoteaux. This spectacular scene from the Gettysburg Cyclorama,

is the artist's impression of Armistead's attack into the Angle. The painting was first shown in Boston before it was moved

to Gettysburg in 1913. Gettysburg NMP.

| Brig. Gen. Webb |

|

| (Gettysburg NMP) |

| 69th Pennsylvania Infantry |

|

| (National Archives) |

(Left) Picture of officers from the 69th Pennsylvania Infantry, one

of the regiments under General Webb that threw back Pickett's men. Propped against the tent behind the group are the flags

of the regiment. Composed of Irish immigrants and American-born Irishmen from Philadelphia, the 69th bore a green regimental

color as well as the United States flag in their precarious position just in front of the copse of trees. National Archives.

At the wall were two of Webb's larger regiments, the 69th Pennsylvania

and eight companies of the 71st Pennsylvania. His last regiment, the 72nd Pennsylvania and two companies of the 106th Pennsylvania

Infantry were on the reverse side of Cemetery Ridge. Webb sent orders for these to come forward as Pickett's Confederates

swarmed to the Angle. "The enemy advanced steadily to the fence," Webb observed, "driving out a portion of the 71st Pennsylvania

Volunteers." The 71st's soldiers raced back and headlong into the 72nd, which were arriving at the crest. The intermingled

regiments opened a crash of rifle fire into the Angle, cutting down friend and foe alike in the dense smoke that began to

obscure the battle positions. Webb ran to the front of the 72nd in an attempt to order

them to charge, but no one could distinguish his commands above the perfect roar of musketry. Moments later, the southerners

dashed over the wall. "General Armistead passed over the fence with probably over 100 of his command and several

battle flags," Webb reported. "The 72nd Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered up to hold the crest and advanced to within forty

paces of the enemy's line. The 69th Pennsylvania and most of the 71st Pennsylvania, even after the enemy were in their

rear, held their position."

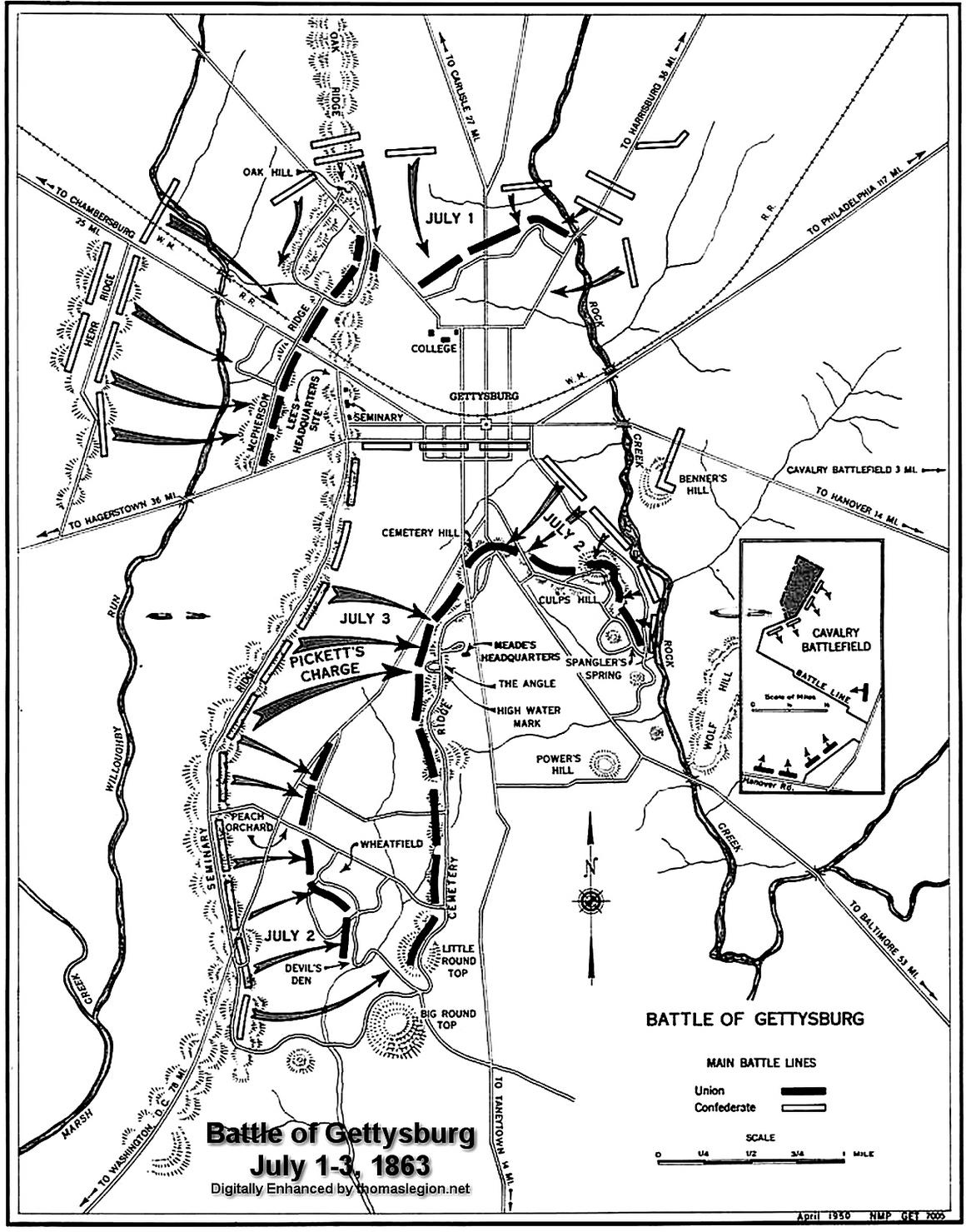

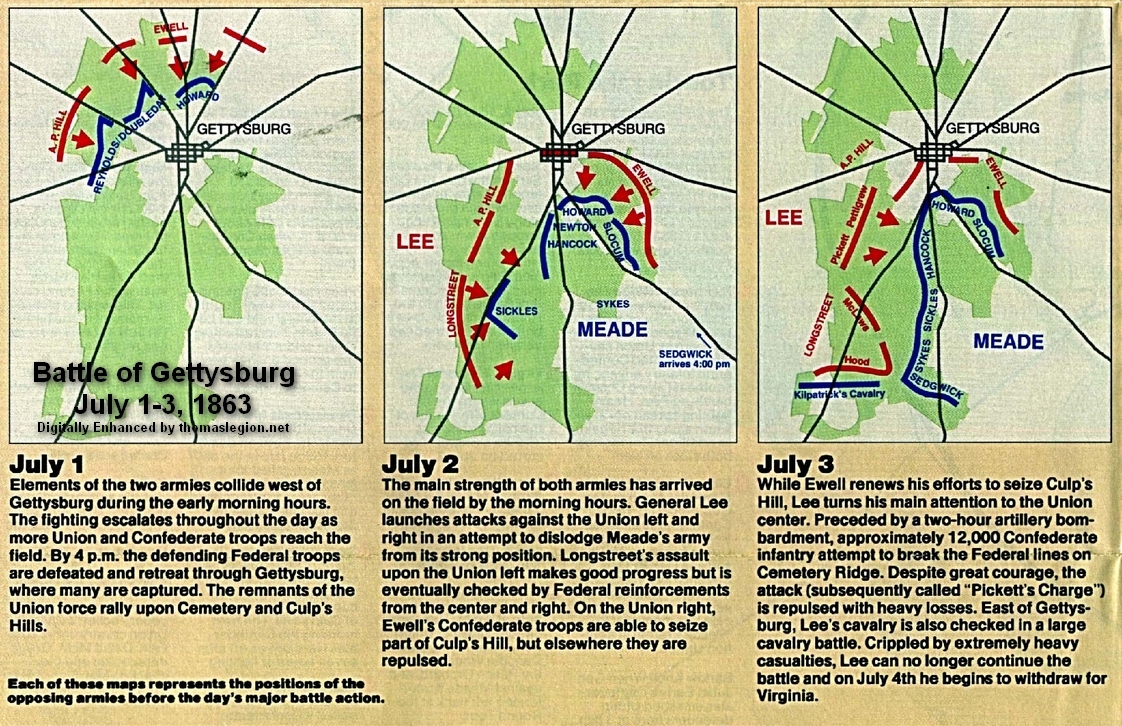

| Battle of Gettysburg July 1-3, 1863 Map |

|

| The Angle, High Water Mark, Battle of Gettysburg Map |

| 69th Pennsylvania Monument |

|

| (Gettysburg NMP) |

(Right) Photograph of view toward the Codori farm buildings from the Philadelphia Brigade Monument (at left)

in the Angle. The monument to the 69th Pennsylvania Infantry stands in the middle distance at the stone wall they held during

the battle. Gettysburg NMP.

Congregating along the stone wall in front of the Union positions, the Virginians from Garnett's brigade

mixed with soldiers from Pettigrew's column had been temporarily blocked by the storm of rifle fire from the Philadelphians.

Regiments were hopelessly intermingled and all order was lost. Pushing his way through the crowd with sword and hat still

held high, General Lewis Armistead reached the soldiers by the fence. Though everyone was loading and firing at Webb's men, no one had yet crossed

over. "We cannot stay here," he roared. "Give them the cold steel, boys!" Armistead leapt the wall, followed by a handful

of his soldiers. More followed. Racing through the dense smoke, Armistead placed a hand upon an abandoned cannon where he

suddenly fell, pierced through one arm by a minie ball. More southerners braved the fire to crowd around the fallen general

and the angle was filled with red battle flags defiantly waving above the abandoned Union guns. Approximately 200 or more

Confederates moved into the copse of trees to fire into the back of Union regiments still holding the stone wall. Union troops

rushed into the small woods, headlong into the Confederates. Soldiers fired weapons at close range, rifles were swung as clubs,

and bayonets thrust at the mass of bodies swirling through the trees, smoke and dust. The crisis of the battle had arrived;

it was the "High Water Mark".

| Pickett's Charge |

|

| (National Archives) |

(Left) Picture of "Pickett's Charge", drawn soon after the battle for a New York newspaper by Alfred

Waud. National Archives.

The intermingled commands of southern troops were soon leaderless as more and more officers fell, killed

or wounded. Crowded at the wall, many looked to the rear for the promised supports that never came. South of the Angle, two

regiments from Vermont had swung out in front of the Union line and fired into the flank of the Confederates around the wall,

shattering General Kemper's Brigade and crowding the survivors into the rest of the division. Officers desperately tried to rally their men to make

a stand, but there was no escape from the brutal fire. The southerners either ran or fell flat to the ground to hide from

the deadly volleys. In twos and threes, men started back to the Emmitsburg Road through the hail of gunfire- some walking

and others trotting, while a number of panic stricken men ran as fast as their legs could carry them. Sensing that the Confederates

were about ready to break, the 72nd "Fire Zouaves" suddenly charged into the Angle to retake Cushing's guns. Confederates

who could not escape threw down their weapons and raised their hands. Those who resisted were struck down with clubbed muskets

and fists. The shooting died away as quickly as it had started. Pickett's Charge had failed. In the aftermath, Union soldiers rounded up both the living and dying in front the wall. Flags,

swords, rifles and pistols were scooped up as prizes. The dead and wounded lay in heaps where canister had done its deadly

work. In the Angle, Lt. Cushing's battery was a shambles of bullet ridden gun carriages and wrecked limbers, dead teams of

horses still strapped into their harnesses. Dead and wounded men lay scattered about the trees and throughout the brush and

grass.

All three of Pickett's generals were lost, as well as most of his colonels.

Generals Gibbon and Webb were both seriously wounded as was General Hancock, shot while directing the Vermont troops in their attack on Pickett's flank. A bullet passed through the pommel

of his saddle and into his groin, carrying a nail with it and ripping open an artery. Quick-thinking aides applied a tourniquet

to the general's leg while he dictated a note to General Meade on the Confederate repulse, adding "they must be low on ammunition

for I was shot with a 10-penny nail." Hancock would eventually recover from his wound, but it would bother him with reoccurring

infections for the remainder of his life

The ferocity of those long minutes spent within the area known as the Angle

is difficult to imagine today. Cannon sit on iron carriages to mark the location of Cushing's guns, while at the wall stands

monuments to three of Webb's regiments that turned back Garnett's and Armistead's soldiers- mute testaments to the horrors

that took place at this site that afternoon.

| Pickett's Charge, July 3, 1863 |

|

| Three Day Battle of Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863 |

Sources: Gettysburg National Military Park; National Park Service; Library of Congress; Official Records

of the Union and Confederate Armies.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's Charge,

by George Stewart. Description: The author has written

an eminently readable, thoroughly enjoyable, and well-researched book on the third day of the Gettysburg battle, July 3, 1863. An especially rewarding read if one has toured, or plans

to visit, the battlefield site. The author's unpretentious, conversational style of writing succeeds in putting the reader

on the ground occupied by both the Confederate and Union forces before, during and after

Pickett's and Pettigrew's famous assault on Meade's Second Corps. Continued below...

Interspersed

with humor and down-to-earth observations concerning battlefield conditions, the author conscientiously describes all aspects

of the battle, from massing of the assault columns and pre-assault artillery barrage to the last shots and the flight of the

surviving rebels back to the safety of their lines… Having visited Gettysburg several years ago, this superb volume makes me

want to go again.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's

Charge in History and Memory. Description:

Pickett's Charge--the Confederates' desperate (and failed) attempt to break the Union lines on the third and final day of

the Battle of Gettysburg--is best remembered as the turning point of the U.S. Civil War. But Penn State historian Carol Reardon reveals

how hard it is to remember the past accurately, especially when an event such as this one so quickly slipped into myth. Continued below...

She writes, "From the time the battle smoke cleared, Pickett's

Charge took on this chameleon-like aspect and, through a variety of carefully constructed nuances, adjusted superbly to satisfy

the changing needs of Northerners, Southerners, and, finally, the entire nation." With care and detail, Reardon's fascinating book teaches a lesson in the uses and misuses

of history.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's

Charge--The Last Attack at Gettysburg (Hardcover).

Description: Pickett's Charge is probably the best-known military engagement of the Civil War, widely regarded as the defining

moment of the battle of Gettysburg and celebrated as the high-water

mark of the Confederacy. But as Earl Hess notes, the epic stature of Pickett's Charge has grown at the expense of reality,

and the facts of the attack have been obscured or distorted by the legend that surrounds them. With this book, Hess sweeps

away the accumulated myths about Pickett's Charge to provide the definitive history of the engagement.

Drawing on

exhaustive research, especially in unpublished personal accounts, he creates a moving narrative of the attack from both Union and Confederate

perspectives, analyzing its planning, execution, aftermath, and legacy. He also examines the history of the units involved,

their state of readiness, how they maneuvered under fire, and what the men who marched in the ranks thought about their participation

in the assault. Ultimately, Hess explains, such an approach reveals Pickett's Charge both as a case study in how soldiers

deal with combat and as a dramatic example of heroism, failure, and fate on the battlefield.

Recommended Reading: Into the Fight: Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg.

Description: Challenging conventional views, stretching

the minds of Civil War enthusiasts and scholars as only John Michael Priest can, Into the Fight is both a scholarly and a

revisionist interpretation of the most famous charge in American history. Using a wide array of sources, ranging from the

monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield to the accounts of

the participants themselves, Priest rewrites the conventional thinking about this unusually emotional, yet serious, moment

in our Civil War.

Starting with

a fresh point of view, and with no axes to grind, Into the Fight challenges all interested in that stunning moment in history

to rethink their assumptions. Worthwhile for its use of soldiers’ accounts, valuable for its forcing the reader to rethink

the common assumptions about the charge, critics may disagree with this research, but they cannot ignore it.

Recommended Reading:

Lost Triumph: Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg--And Why It Failed.

Description: A fascinating narrative-and a bold

new thesis in the study of the Civil War-that suggests Robert E. Lee had a heretofore undiscovered strategy at Gettysburg

that, if successful, could have crushed the Union forces and changed the outcome of the war. The Battle of Gettysburg is the

pivotal moment when the Union forces repelled perhaps America's greatest

commander-the brilliant Robert E. Lee, who had already thrashed a long line of Federal opponents-just as he was poised at

the back door of Washington, D.C.

It is the moment in which the fortunes of Lee, Lincoln, the Confederacy, and the Union hung precariously in the balance. Conventional wisdom has held to date, almost without exception,

that on the third day of the battle, Lee made one profoundly wrong decision. But how do we reconcile Lee the high-risk warrior

with Lee the general who launched "Pickett's Charge," employing only a fifth of his total forces, across an open field, up

a hill, against the heart of the Union defenses? Most history books have reported that Lee just had one very bad day. But

there is much more to the story, which Tom Carhart addresses for the first time. Continued below...

With meticulous

detail and startling clarity, Carhart revisits the historic battles Lee taught at West Point and believed were the essential

lessons in the art of war-the victories of Napoleon at Austerlitz, Frederick the Great at Leuthen, and Hannibal at Cannae-and

reveals what they can tell us about Lee's real strategy. What Carhart finds will thrill all students of history: Lee's plan

for an electrifying rear assault by Jeb Stuart that, combined with the frontal assault, could have broken the Union forces

in half. Only in the final hours of the battle was the attack reversed through the daring of an unproven young general-George

Armstrong Custer. About the Author: Tom Carhart has been a lawyer and a historian for the Department of the Army in Washington, D.C. He is

a graduate of West Point, a decorated Vietnam veteran, and has earned a

Ph.D. in American and military history from Princeton University. He is the author of four books of military history and teaches at Mary Washington College

near his home in the Washington, D.C.

area.

Recommended Reading:

General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse. Review:

You cannot say that University of North

Carolina professor Glatthaar (Partners in Command) did not do his homework in this massive examination

of the Civil War–era lives of the men in Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Glatthaar spent nearly 20 years

examining and ordering primary source material to ferret out why Lee's men fought, how they lived during the war, how they

came close to winning, and why they lost. Glatthaar marshals convincing evidence to challenge the often-expressed notion that

the war in the South was a rich man's war and a poor man's fight and that support for slavery was concentrated among the Southern

upper class. Continued below...

Lee's army

included the rich, poor and middle-class, according to the author, who contends that there was broad support for the war in

all economic strata of Confederate society. He also challenges the myth that because Union forces outnumbered and materially

outmatched the Confederates, the rebel cause was lost, and articulates Lee and his army's acumen and achievements in the face

of this overwhelming opposition. This well-written work provides much food for thought for all Civil War buffs.

Recommended Reading: ONE CONTINUOUS FIGHT: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, July

4-14, 1863 (Hardcover) (June 2008). Description: The titanic three-day battle of Gettysburg

left 50,000 casualties in its wake, a battered Southern army far from its base of supplies, and a rich historiographic legacy.

Thousands of books and articles cover nearly every aspect of the battle, but not a single volume focuses on the military aspects

of the monumentally important movements of the armies to and across the Potomac River. One

Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit

of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863 is the first detailed military history of Lee's retreat and the Union

effort to catch and destroy the wounded Army of Northern Virginia. Against steep odds and encumbered with thousands of casualties,

Confederate commander Robert E. Lee's post-battle task was to successfully withdraw his army across the Potomac River. Union

commander George G. Meade's equally difficult assignment was to intercept the effort and destroy his enemy. The responsibility

for defending the exposed Southern columns belonged to cavalry chieftain James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart. If Stuart fumbled

his famous ride north to Gettysburg, his generalship during

the retreat more than redeemed his flagging reputation. The ten days of retreat triggered nearly two dozen skirmishes and

major engagements, including fighting at Granite Hill, Monterey Pass,

Hagerstown, Williamsport, Funkstown,

Boonsboro, and Falling Waters. Continued

below...

President Abraham

Lincoln was thankful for the early July battlefield victory, but disappointed that General Meade was unable to surround and

crush the Confederates before they found safety on the far side of the Potomac. Exactly what Meade did to try to intercept the fleeing Confederates, and how the

Southerners managed to defend their army and ponderous 17-mile long wagon train of wounded until crossing into western Virginia on the early morning of July 14, is the subject of this study.

One Continuous Fight draws upon a massive array of documents, letters, diaries, newspaper accounts, and published primary

and secondary sources. These long-ignored foundational sources allow the authors, each widely known for their expertise in

Civil War cavalry operations, to describe carefully each engagement. The result is a rich and comprehensive study loaded with

incisive tactical commentary, new perspectives on the strategic role of the Southern and Northern cavalry, and fresh insights

on every engagement, large and small, fought during the retreat. The retreat from Gettysburg

was so punctuated with fighting that a soldier felt compelled to describe it as "One Continuous Fight." Until now, few students

fully realized the accuracy of that description. Complimented with 18 original maps, dozens of photos, and a complete driving

tour with GPS coordinates of the entire retreat, One Continuous Fight is an essential book for every student of the American

Civil War in general, and for the student of Gettysburg in

particular. About the Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg has written widely on Civil War cavalry operations. His books include Glory

Enough for All (2002), The Union Cavalry Comes of Age (2003), and The Battle of Monroe's Crossroads and the Civil War's Final

Campaign (2005). He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

J. David Petruzzi is the author of several magazine articles on Eastern Theater cavalry operations, conducts tours of cavalry

sites of the Gettysburg Campaign, and is the author of the popular "Buford's Boys." A long time student of the Gettysburg

Campaign, Michael Nugent is a retired US Army Armored Cavalry Officer and the descendant of a Civil War Cavalry soldier. He

has previously written for several military publications. Nugent lives in Wells, Maine.

|