|

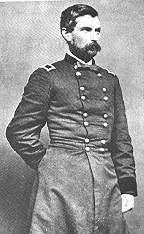

General John Gibbon and Iron Brigade at Battle of Gettysburg

"How long did this pandemonium last?"

| General John Gibbon |

|

| National Archives |

General John Gibbon was wounded during Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. He had assumed command of the 2nd Corps when General Winfield Scott Hancock was assigned to command a larger portion of the field.

On July 3rd, after sharing a noon-time meal of stewed rooster and coffee with General Meade, Gibbon and his staff were lounging near the Union center when the Confederate

artillery barrage began. In his book, Personal Recollections of the Civil War, General Gibbon vividly recalled:

"How long we sat there it is impossible to say but after a long silence

along the line a single gun was heard off in my front and everyone's attention was attracted. Almost instantly afterwards

the whole air above and around us was filled with bursting and screaming projectiles, and the continuous thunder of the guns,

telling us that something serious was at hand. All jumped to their feet and loud calls were made for horses, which orderlies

hurried forward... I started on a run, up a little swale leading directly up to the center. The thunder of the guns was incessant,

for all ours had now opened fire and the whole air seemed filled with rushing, screaming and bursting shells.

"The larger round shells could be seen plainly as in their nearly completed

course they curved in their fall towards the Taneytown Road, but the long rifled shells came with a rush and a scream and

could only be seen in their rapid flight when they 'upset' and went tumbling through the air, creating the uncomfortable impression

that, no matter whether you were in front of the gun from which they came or not, you were liable to be hit. Every moment

or so one would burst, throwing its fragments about in a most disagreeably promiscuous manner, or first striking the ground,

plough a great furrow in the earth and rocks... throwing these last about in a way quite as dangerous as the pieces of the

exploding shell. At last I reached the brow of the hill to find myself in the most infernal pandemonium it has ever been my

fortune to look upon. Very few troops were in sight and those that were, were hugging the ground closely, some behind the

stone wall, some not, but the artillerymen were all busily at work at their guns, thundering out defiance to the enemy whose

shells were bursting in and around them at a fearful rate, striking now a horse, now a limber box and now a man. Over all

hung a heavy pall of smoke underneath which could be seen the rapidly moving legs of the men as they rushed to and fro between

the pieces and the line of limbers, carrying forward the ammunition. One thing which forcibly occurred to me was the perfect

quiet with which the horses stood in their places. Even when a shell, striking in the midst of a team, would knock over one

or two of them or hurl one struggling in his death agonies to the ground, the rest would make no effort to struggle or escape

but would stand stolidly by as if saying to themselves, 'It is fate. It is useless to try to avoid it.' Looking thus at Cushing's

Battery, my eyes happened to rest upon one of the gunners standing in rear of the nearest limber, the lid open showing the

charges. Suddenly, with a shriek, came a shell right under the limber box and the poor gunner went hopping to the rear on

one leg, the shred of the other dangling about as he went.

"As I reached the line just to the left of Cushing's Battery,

I found General Webb seated on the ground as coolly as though he had no interest in the scene and somehow it seemed to me

that in such a place men appear to take things a good deal as I had remarked the horses took them. Of course it would be absurd

to say we were not scared. None but fools, I think, can deny that they are afraid in battle.

"How long did this pandemonium

last? Measured by our feelings it might have been an age. In point of fact it may have been an hour or three or five. The

measurement of time under such circumstances, regular as it is by the watch, is exceedingly uncertain by the watchers. Getting

tired of seeing men and horses torn to pieces and observing that although some of the shells struck and burst among us, most

of them went high and burst behind us, the idea occurred to me that a position farther to the front would be safer and rising

to my feet, I walked forward accompanied by my aide (Lt. Frank Haskell). I had made but a few steps when three of Cushing's

limber boxes blew up at once, sending the contents in a vast column of dense smoke high up in the air and above the din could

be heard the triumphant yells of the enemy as he recognized this result of his fire. We walked forward to the fence where

the men were lying close behind it and motioning them to make room for me, I stepped over the wall, went to a little clump

of bushes standing just in front of the line and looked out there to see if I could detect any movement going on in that direction.

Nothing could be seen but the smoke constantly issuing from the long line of batteries and nothing heard but the continuous

roar of hundreds of guns, the screaming of countless projectiles as they rushed through the air in all directions and the

bursting of shells. These all went over our heads and generally burst behind us. Whilst standing here and wondering how all

this din would terminate, Mitchell, and aide of General Hancock, joined me with a message from Hancock to know what I thought

the meaning of this terrific fire. I replied I thought it was the prelude either to a retreat or an assault. After standing

here for some time and finding the enemy did not lessen the elevation of his pieces, we walked down to the left still outside

the line of battle, the men peering at us curiously from behind the stone wall as we passed.

"The fire on both sides

now had considerably slackened and only a few shells were coming from the enemy's guns. As we walked towards the right, a

staff officer with an orderly leading my horse met me with information that the enemy was coming in force. I hurriedly mounted

and rode to the top of the hill where a magnificent sight met my eyes. The enemy in a long grey line was marching towards

us over the rolling ground in our front, their flags fluttering in the air and serving as guides to their line of battle.

In front was a heavy skirmish line which was driving ours on a run. Behind the front line another appeared and finally a third

and the whole came on like a great wave of men, steadily and stolidly. Hastily telling Haskell to ride to General Meade and

tell him the enemy was coming upon us in force and we should need all the help he could send us, I directed the guns of Arnold's

Battery to be run forward to the wall loaded with double rounds of canister and then rode down my line and cautioned the men

not to fire until the first line crossed the Emmitsburg Road. By this time the bullets were flying pretty thickly along the

line and the batteries from other portions of the field had opened fire upon the moving mass in front of us. The front line

reached the Emmitsburg Road and hastily springing over the two fences, paused a moment to reform and then started up the slope.

My division, up to this time, had fired but little but now from the low stone wall on each side of the angle every gun along

it sent forth the most terrific fire. From my position on the left I could see the terrible effect of this. Mounted officers

in the rear were seen to go down before it and as the rear lines came up and clambered over the fences, men fell from the

top rails, but the mass still moved on up to our very guns and the stone wall in front. I noticed after all three lines closed

up, that the men on the right of the assaulting force were continually closing in to their left, evidently to fill the gaps

made by our fire and that the right of their line was hesitating behind the clump of bushes where I had stood during the cannonade.

To our left of this point was a regiment of our division and desirous of aiding in the desperate struggle now taking place

on the hill to our right, I endeavored to get this regiment to swing out to the front, by a change front forward on the right

company, take the enemy's line in flank to sweep up along the front of our line. But in the noise and turmoil of the conflict

it was difficult to get my orders understood. Few unacquainted with the rigid requirements of discipline and of how an efficient

military organization must necessarily be a machine which works at the will of one man as completely as a locomotive obeys

the will of the engineer... in everything which the locomotive was built to obey, can appreciate the importance of drill and

discipline in a crisis like the one now facing us.

"In my eagerness to get the regiment to swing out and do what I

wanted, I spurred my horse in front of it and waved forward the left flank. I was suddenly recalled to the absurd position

I had assumed by the whole regiment opening fire! I got to the rear as soon as possible. I galloped back to my own division

and attempted to get the left of that to swing out. Whilst so engaged I felt a stinging blow apparently behind the left shoulder.

"I

soon began to grow faint from the loss of blood which was trickling from my left hand. I directed Lt. Moale, my aide, to turn

over the command of the division to General Harrow and in company with another staff officer, Captain Francis Wessells, 106th

Pennsylvania, (I) left the field, the sounds of the conflict on the hill still ringing in my ears."

| General Gibbon Monument at Gettysburg |

|

| Gettysburg NMP |

General Gibbon eventually recovered from his wound at Gettysburg and returned to the Army of the Potomac in early 1864 to command his old division (the 2nd) of the Second Corps, once again under his old friend Winfield

Scott Hancock. Gibbon led his division during the bloody Wilderness Campaign that spring and distinguished himself in action at the battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia. His division participated in some of the heaviest fighting yet seen during the war, especially on

May 12 at another "Bloody Angle" called the "Mule Shoe". By the time his command had reached the battlefield of Cold Harbor in early June, many of his regiments numbered

barely 100 men and were commanded by captains or lieutenants. In 1865, Gibbon received a promotion to the rank major general

and was assigned to command the Twenty Fourth Army Corps in the Army of The James, which he led to Appomattox Court House. It was the timely arrival of Gibbon's troops west of the court house on the morning of April 9, 1865, that

effectively blocked Lee's escape route to Farmville, leading to Lee's decision to meet with General Grant that afternoon to

discuss surrender terms.

After the close of the Civil War, General Gibbon returned to regular army

service and was assigned to command infantry units on the western plains, where he participated in numerous campaigns against

plains tribes during several uprisings in the 1870's and 1880's. General Gibbon died in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1891 and is

interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

(Sources listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended Reading:

THOSE DAMNED BLACK HATS!: The Iron Brigade in the Gettysburg Campaign. Description: The Iron Brigade--an all-Western outfit famously branded as The

Iron Brigade of the West--served their enlistments entirely in the Eastern Theater. Hardy men were these soldiers from Indiana, Wisconsin,

and Michigan, who waged war beneath their unique black Hardee Hats on many fields, from Brawner's

Farm during the Second Bull Run Campaign all the way to Appomattox.

In between were memorable combats at South Mountain,

Antietam, Chancellorsville, Mine Run, the Overland Campaign, and the grueling fighting around Petersburg. None of these battles compared with the "four long hours" of July 1, 1863, at

Gettysburg, where the Iron Brigade was all but wrecked. Lance

Herdegen's Those Damned Black Hats! The Iron Brigade in the Gettysburg Campaign is the first book-length account of their

remarkable experiences in Pennsylvania during that fateful

summer of 1863. Continued below..

Drawing upon

a wealth of sources, including dozens of previously unpublished accounts, Herdegen details for the first time the exploits

of the 2nd, 6th, 7th Wisconsin,

19th Indiana, and 24th Michigan

regiments during the entire campaign. On July 1, the Western troops stood line-to-line and often face-to-face with their Confederate

adversaries, who later referred to them as "those damned Black Hats!" With the help of other stalwart comrades, the Hoosiers,

Badgers, and Wolverines shed copious amounts of blood to save the Army of the Potomac's defensive

position west of town. Their heroics above Willoughby Run, along the Chambersburg Pike, and at the Railroad Cut helped define

the opposing lines for the rest of the battle and, perhaps, won the battle that helped preserve the Union. Herdegen's account is much

more than a battle study. The story of the fighting at the "Bloody Railroad Cut" is well known, but the attack and defense

of McPherson's Ridge, the final stand at Seminary Ridge, the occupation of Culp's Hill, and the final pursuit of the Confederate

Army has never been explored in sufficient depth or with such story telling ability. Herdegen completes the journey of the

Black Hats with an account of the reconciliation at the 50th Anniversary Reunion and the Iron Brigade's place in Civil War

history. "Where

has the firmness of the Iron Brigade at Gettysburg been surpassed in history?"

asked Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin. Indeed, it was a

fair question. The brigade marched to Gettysburg with 1,883

men in ranks and by nightfall on July 1, only 671 men were counted. It would fight on to the end of the Civil War, and do

so without its all-Western composition, but never again was it a major force in battle. Some 150 years after the last member of the Iron Brigade laid down his life for his country,

the complete story of what the Black Hats did at Gettysburg

and how they remembered it is finally available.

Related Studies:

Recommended Reading: Iron Brigade:

A Military History (Indiana University Press). Description: This is a excellent account of the Iron Brigade, the "Black Hat Brigade",

the only all western brigade in the Eastern army. This Federal unit fought valiantly at 2nd Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg,

Chancellorsville and at the "High Water Mark" at Gettysburg. It

is a well-written book and also includes battle narratives and comprehensive--and easy to read--maps. Continued

below.

"...This is the definitive history of what I consider the best brigade-sized unit in either army during

the Civil War..." "The battle-torn Iron Brigade

contains the most stirring description of the 1st day of battle at Gettysburg that I have ever read..."

Recommended Reading: A Brotherhood Of Valor: The Common Soldiers

Of The Stonewall Brigade C.S.A. And The Iron Brigade U.S.A. Description: Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson was arguably the greatest commander of the Civil War. Yet, "Stonewall"

Jackson owed much of his success to the troops who served

under his command. He eagerly gave them their due: "You cannot praise these men of my brigade too much; they have fought,

marched, and endured more than I even thought they would." The Stonewall Brigade, composed mainly of Virginians from the Shenandoah

Valley, proved its mettle at First Manassas and never let up--even after its esteemed leader was shot down at Chancellorsville.

Their equally elite counterparts in the Army of the Potomac were known as the Iron Brigade, hardy westerners drawn from Wisconsin, Indiana, and Michigan.

By focusing on these two groups, historian Jeffry Wert retells the story of the Civil War's eastern theater as it was experienced

by these ordinary men from North and South. Continued below.

His battle

descriptions are riveting, especially when he covers Antietam:

Three times

the Georgians charged towards the guns, and three times they were repelled. Union infantry west of the battery ripped apart

the attacker's flank, and the artillerists unleashed more canister.... Finally, the Georgians could withstand the punishment

no longer, and as more Union infantry piled into the Cornfield, Hood's wrecked division retreated towards West Woods and Dunker Church. When

asked later where his command was, Hood replied, "Dead on the field."

But the book

is perhaps most notable for the way in which it describes the everyday hardships befalling each side. They often lacked food,

shoes, blankets, and other military necessities. When the war began, the men believed deeply in their conflicting causes.

Before it was over, writes Wert, "the war itself became their common enemy." Wert is slowly but surely gaining a reputation

as one of the finest popular historians writing about the Civil War; A Brotherhood of Valor will undoubtedly advance his claim.

Recommended Reading: Four Years with the

Iron Brigade: The Civil War Journal of William Ray, Seventh Wisconsin

Volunteers (Hardcover). Description: The recently discovered journal of William Ray of the Seventh Wisconsin is the most

important primary source ever of soldier life in one of the war's most famous fighting units. No other collection of letters

or diaries comes close to it. Two days before his regiment left Wisconsin

in 1861, the twenty-three-year-old blacksmith began, as he described it, "to keep account" of his life in what became the

"Iron Brigade of the West." Continued below.

Ray's journal encompasses all

aspects of the enlisted man's life-the battles, the hardships, and the comradeship. And Ray saw most of the war from the front

rank. He was wounded at Second Bull Run, again at Gettysburg, and yet a third time in the hell of the Wilderness.

He penned something in his journal almost every day-occasionally just a few lines, at other times thousands of words. Ray's

candid assessments of officers and strategy, his vivid descriptions of marches and the fighting, and his evocative tales of

foraging and daily army life fill a large gap in the historical record and give an unforgettable soldier's-eye view of the

Civil War.

Recommended Reading: The Men Stood Like Iron: How the Iron Brigade Won Its Name. Description:

No volunteers tramped with more innocent resolve on the drill fields of 1861 than the farmers, immigrants, shopkeepers, and

"piney" camp boys who volunteered for the Second, Sixth, and Seventh Wisconsin and the Nineteenth Indiana Infantry. The Men

Stood Like Iron is the moving, often melancholy, story of how the backwoods "Calico boys" became soldiers of the celebrated

"Iron Brigade."

Recommended

Reading:

The History Buff's Guide to Gettysburg (Key People, Places,

and Events) (Key People, Places, and Events). Description: While most history books are dry monologues of people, places,

events and dates, The History Buff's Guide is ingeniously written and full of not only first-person accounts but crafty prose.

For example, in introducing the major commanders, the authors basically call Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell a chicken

literally. 'Bald, bug-eyed, beak-nosed Dick Stoddard Ewell had all the aesthetic charm of a flightless foul.' Continued below.

To balance

things back out a few pages later, they say federal Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade looked like a 'brooding gargoyle with an

intense cold stare, an image in perfect step with his nature.' Although it's called a guide to Gettysburg,

in my opinion, it's an authoritative guide to the Civil War. Any history buff or Civil War enthusiast or even that casual

reader should pick it up.

Sources: John Gibbon, Personal Recollections of the Civil War, G. P. Putnam's

Sons, New York, 1928; George R. Stewart, Pickett's Charge, A Microhistory of the Final Attack at Gettysburg, July 3, 1863,

Press of Morningside Bookshop, Dayton, 1980; Gettysburg National Military Park.

|