|

Spangler's Spring

Battle of Gettysburg

Spangler's Spring and Battle of Gettysburg

Introduction

The Battle of Spangler's Spring occurred on the second day of the engagement of Gettysburg.

The second day, July 2, 1863, consisted of fighting at Devil’s Den, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, the Peach

Orchard, Cemetery Ridge, Trostle’s Farm, Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, and involved at least 100,000 soldiers

of which roughly 20,000 were killed, wounded, captured or missing. The second day in itself ranks as the 10th bloodiest battle

of the Civil War—with far more casualties than the much larger Battle of Fredericksburg.

Summary

The Battle of Spangler's Spring was contested during the

second day of fighting at Gettysburg near a meadow and was bordered one end by Rock Creek and at its western edge

by the Baltimore Pike and Powers Hill. This action was one of many smaller engagements that was fought throughout the

three day Battle of Gettysburg during July 1-3, 1863. It was strategically joined with the nearby Battle of Culp's Hill and highly written about Battle of the Peach Orchard. The battle, fought within the larger campaign and battle of

Gettysburg, opened on July 2, 1863, and at the time that many other adjacent fields were being contested with cavalry, artillery,

and the push of infantry. Spangler's Spring, an important field having good drinking water, was to be shelled by nearby

artillery on Baltimore Pike and be the scene of bloody infantry charges, but the action, being a footnote by many authors, has

been overshadowed by the well-know battles of the Peach Orchard and Culp's Hill.

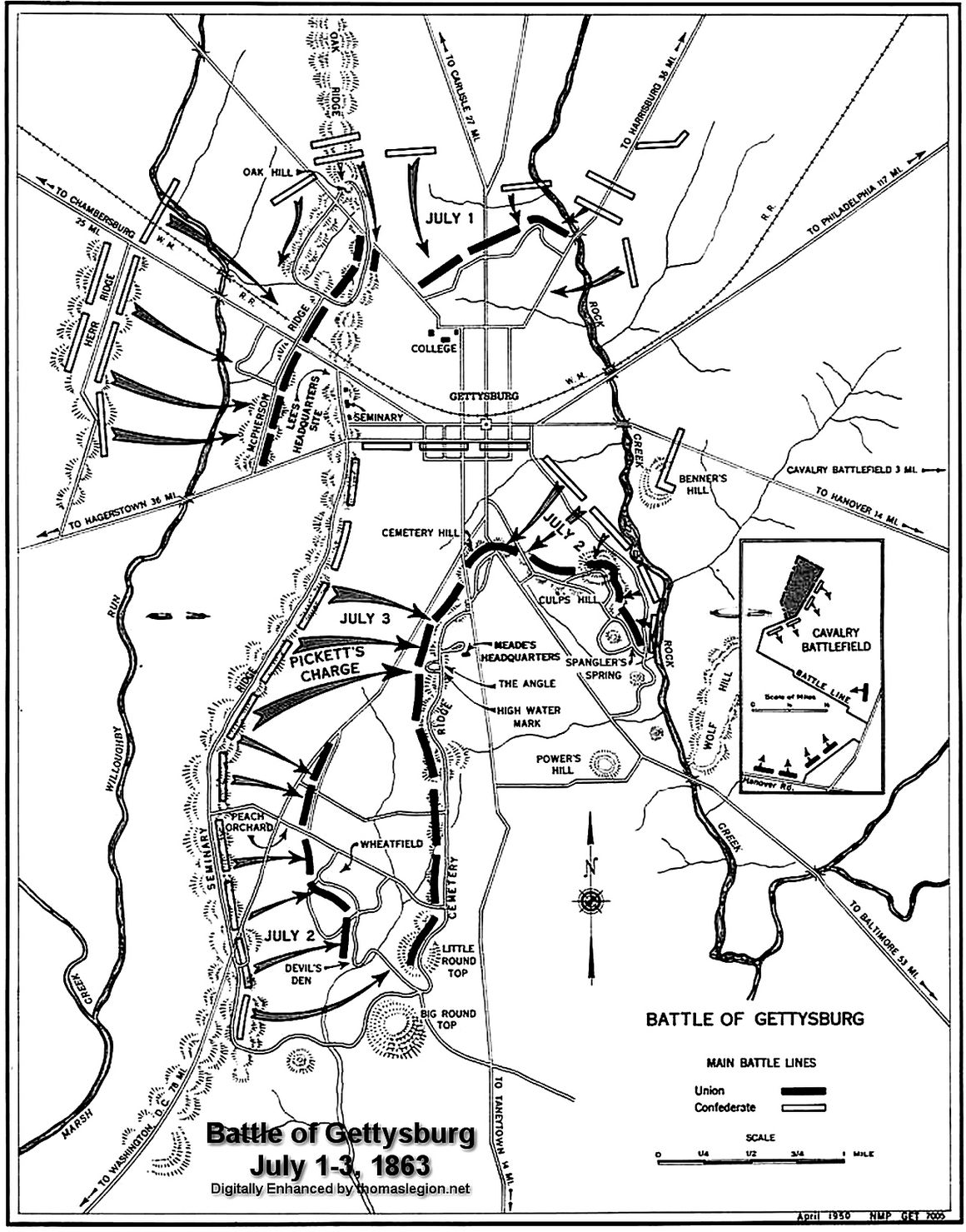

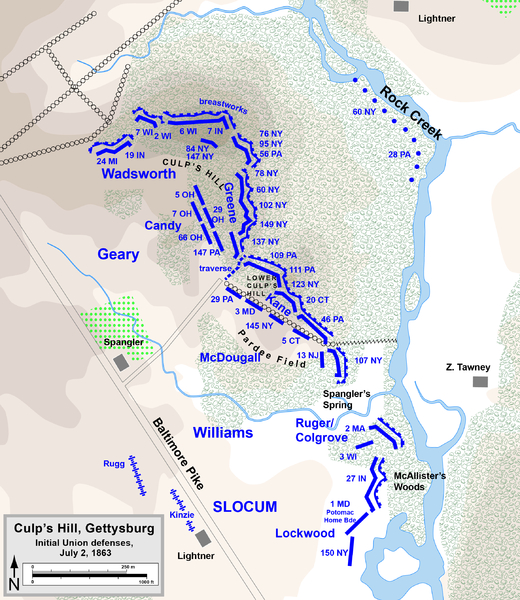

The map below shows Spangler's important location and gives

an impression as to why each side would lock in a back and forth fight in hopes of holding the ground.

During several charges many good men fell on this field while trying to take the location. By holding this position it would

enable additional blue or gray clad troops to advance upon and press the enemy from Spangler's. We must charge and take

the ground! barked one officer while sparing the details in a rather matter of fact tone, for he was informed

that the field must be won and held so that command could then move onto, not one battlefield, but the adjacent battlefields.

Years after being wounded during the battle of Spangler's Field, a private wrote that at Gettysburg he had no idea of what

was going on at any of the surrounding battles, because of "the fact that shells rang and balls knocked down trees,"

he said, "and my ears were dulled and the smoke for a short time took my sight." Spangler's Spring was host to the

likes of Gen. George Steuart, Gen. Edward Johnson, Lt. Col. Charles Mudge's fighting regiment, Gen. Walker's determined

brigade, and Gen. Henry Slocum and his headquarters.

| Battle of Spangler's Spring |

|

| Spangler's Spring at southern tip of Culp's Hill. Gettysburg NMP. |

History

A natural spring that flows at the southern end of Culp's Hill, Spangler's Spring is one of the battlefield's most prominent landmarks and for many years prior to the battle

it had provided water to quench the thirst of man and animal alike. Union troops of the Twelfth Corps occupied this area and

constructed earthworks on the knoll north of the spring site. When these troops temporarily left the area on the afternoon

of July 2, General Greene was forced to leave much of it unoccupied as his thin line of troops could not reach the section

of works above the spring. Adjacent to the spring was a large meadow, bordered on one end by Rock Creek and at its western

edge by the Baltimore Pike and Powers Hill where General Henry Slocum had established a headquarters. From this hill, Union

officers and artillerymen could overlook the meadow to Rock Creek, which was effective for Union guns during the daytime,

but Confederates from General Edward Johnson's Division decided to arrive in this area long after nightfall.

Brig. General George "Maryland" Steuart's Brigade came upon these abandoned earthworks in the darkness and

while Steuart's men were initially unopposed, Confederate units adjacent to his ran into Greene's men and fighting broke out.

Steuart reformed his nervous men at the freshly captured works and sent the 10th Virginia Infantry forward as skirmishers

into the black woods where they reached a stone wall bordering a small pasture. Darkness proved to be helpful to the Virginians

but was also a detriment as the officers cold not see any Union positions and had little idea of where they actually were.

"The regiment was compelled to change front to the rear and perpendicular to the wall," Steuart reported, "from behind which

it repulsed a bayonet charge made by a regiment of the enemy." Threatened with another charge that may not be as easily stopped,

"the brigade was ordered back to the works, where it was formed in line of battle, the First Maryland Battalion on the right

and Tenth Virginia on the left, the North Carolina regiments still remaining outside the breastworks. This reconnaissance,

as well as the reports of scouts and the statements of prisoners, gave us the assurance that we had gained an admirable position."

Steuart's troops repelled another Union probe toward the Spangler's Spring area before 11 P.M., when the firing slowly died

away and the night turned strangely quiet. Sensing that more Union opposition may lay in wait if he pursued his attack, General

Johnson ordered Steuart and the rest of his command to halt and occupy the ground where they were while he requested reinforcements

be sent to renew the attack the next morning.

| Spangler's Spring and Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Official Spangler's Spring and Battle of Gettysburg Map |

| Gen. Steuart |

|

| Generals in Gray |

At 4 A.M. when Johnson's men were counter-attacked by returning Twelfth Corps

troops, Steuart's soldiers found themselves trapped on the knoll. His right regiments, the 1st and 3rd North Carolina were

pinned down by strong Union rifle fire coming from the summit and Union regiments that slipped into the woods immediately

west of his position. Union artillery on the Baltimore Pike blasted the trees around his men, defenseless against this terrible

fire.

At the height of the fighting, two Union regiments- the 2nd Massachusetts

and the 27th Indiana, were ordered to send skirmishers toward the knoll where Steuart's men were locked in. By the time the

order was delivered to the commanders of the regiments, it called for a full scale attack. Incredulous, Lt. Colonel Charles

Mudge of the 2nd Massachusetts told his officers, "Boys, it is murder. But these are our orders!" The attack was a disaster.

As the two regiments charged into the meadow just south of the spring, they were hit on three sides by musket fire, not only

from Steuart but Virginians of Brig. General Walker's brigade, who had arrived to support the left of Steuart's line. Both

regiments lost heavily, including Colonel Mudge who was shot dead during the charge.

After seven hours of continuous fighting with no possibility of achieving

any success, General Johnson ordered Steuart to pull his men from the positions here and reform with the division after re-crossing

Rock Creek. For General Maryland Steuart, the fighting had taken a very toll on his command. His 1st Maryland Battalion had

lost 189 soldiers out of 400 present and the two North Carolina regiments of his brigade, the 1st and 3rd, had both lost almost half of their numbers

during the fighting. "My poor boys," the general said as his survivors crawled from the hill, "oh, my poor boys!" The earthworks

were soon reoccupied by Union troops who spent the remainder of the day recovering wounded soldiers and burying the dead of

both armies. "We have just concluded the most severe battle of the War," Colonel George Cobham, 111th Pennsylvania Infantry

wrote to his brother on July 4th, "which has resulted in a complete victory on the Union side. The fighting has lasted two

days and been desperate on both sides. All round me as I write, our men are busy burying the dead. The ground is literally

covered with them and the blood is standing in pools all round me; it is a sickening sight."

| Spangler's Spring |

|

| Battle of Spangler's Spring. Gettysburg NMP. |

(Right) Boulders and rocks like these near Spangler's Spring provided cover

to some of General Steuart's Confederates during the fighting that morning. Photo Gettysburg NMP.

The forest of healthy hardwoods on Culp's Hill bore the scars of this battle

for many years afterward, objects of keen interest to visitors. "The scene of this conflict was covered by a forest of dead

trees," Henry Hunt wrote of Culp's Hill in the 1880's, "leaden bullets proving as fatal to them as to the soldiers whose bodies

were thickly strewn beneath them."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Legend of Spangler's Spring

Located at the southern end of Culp's Hill, Spangler's Spring is adjacent to one of the few open pasture

areas in this part of the battlefield. This natural spring provided a steady supply of clear water to refresh farmer and animal

alike for many years prior to the battle. With throats parched after their long trek to Gettysburg, Union soldiers of the

Twelfth Army Corps relished the water of Spangler's Spring as they gathered on the wooded slopes of Culp's Hill on July 2.

These thirsty troops constructed log and earthen barricades on the hillside before they were marched away to support the crumbling

Union left flank at the Peach Orchard.

| Spangler's Spring in 1863 |

|

| Battles & Leaders |

Later that same night, the Confederates of Brig. General "Maryland" Steuart's Brigade occupied those abandoned

breastworks and also used the spring to fill their canteens. The Union counterattack early the following morning placed the

spring in no man's land. Because it lay in front of the reversed line, the thirsty Southerners could not get back to it without

running the risk of being shot by Union infantrymen who lay no more that 50 feet away. The spring site was reoccupied by Union

troops late on the morning of July 3rd, finally denying its use to the Southerners.

Legends sprouted soon after the battle that temporary truces were called

between the sides so that men from both armies could fill their cups and canteens from this spring. This legend, no doubt,

sprung from the stories told by some of the veterans who visited the battlefield years after the war when tales of cooperation

between soldiers of both sides were popular. It is doubtful, when looking back at the historic evidence, that this actually

occurred because of the location of the spring and the vicious fighting that raged around it. Yet, the legend of those temporary

truces declared at Spangler's Spring is still very strong today.

The fame of Spangler's Spring and its legend eventually led to damage from

so many visitors who trampled its banks and destroyed the stone covers. To preserve the spring, the United States War Department

constructed a permanent stone and concrete cover over it in 1895, with a small metal trap door to gain access to its waters.

A metal dipper was provided for visitors to quench their thirst as the soldiers had done years before. This practice was halted

soon after administration of the battlefield was assigned to the National Park Service. Due to the possibility of ground water

contamination, the waters of Spangler's Spring are no longer available for public consumption.

Analysis

The Union defensive positions on July 2 began in the north with artillery

batteries on Stevens's Knoll, followed by Wadsworth's division of the I Corps, Greene's New York brigade in positions running

north to south on the upper slope, and the brigade of Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Kane connecting to Greene's line behind breastworks

on the lower slope. Behind these front lines were, from left to right, the brigades of Col. Charles Candy, Col. Archibald

L. McDougall, Col. Silas Colgrove, and Brig. Gen. Henry H. Lockwood, extending past Spangler's Spring and through McAllister's

Woods. (The latter three brigades were from the XII Corps division of Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Ruger, who was filling in for Brig.

Gen. Alpheus S. Williams, temporarily in corps command.)

That morning, Gen. Robert E. Lee ordered attacks on both ends of the Union

line. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet attacked with his First Corps on the Union left (Little Round Top, Devil's Den, the Wheatfield).

Ewell and the Second Corps were assigned the mission of launching a simultaneous demonstration against the Union right, a

minor attack that was intended to distract and pin down the Union defenders against Longstreet. Ewell was to exploit any success

his demonstration might achieve by following up with a full-scale attack at his discretion.

| Spangler's Spring and Battle of Gettysburg |

|

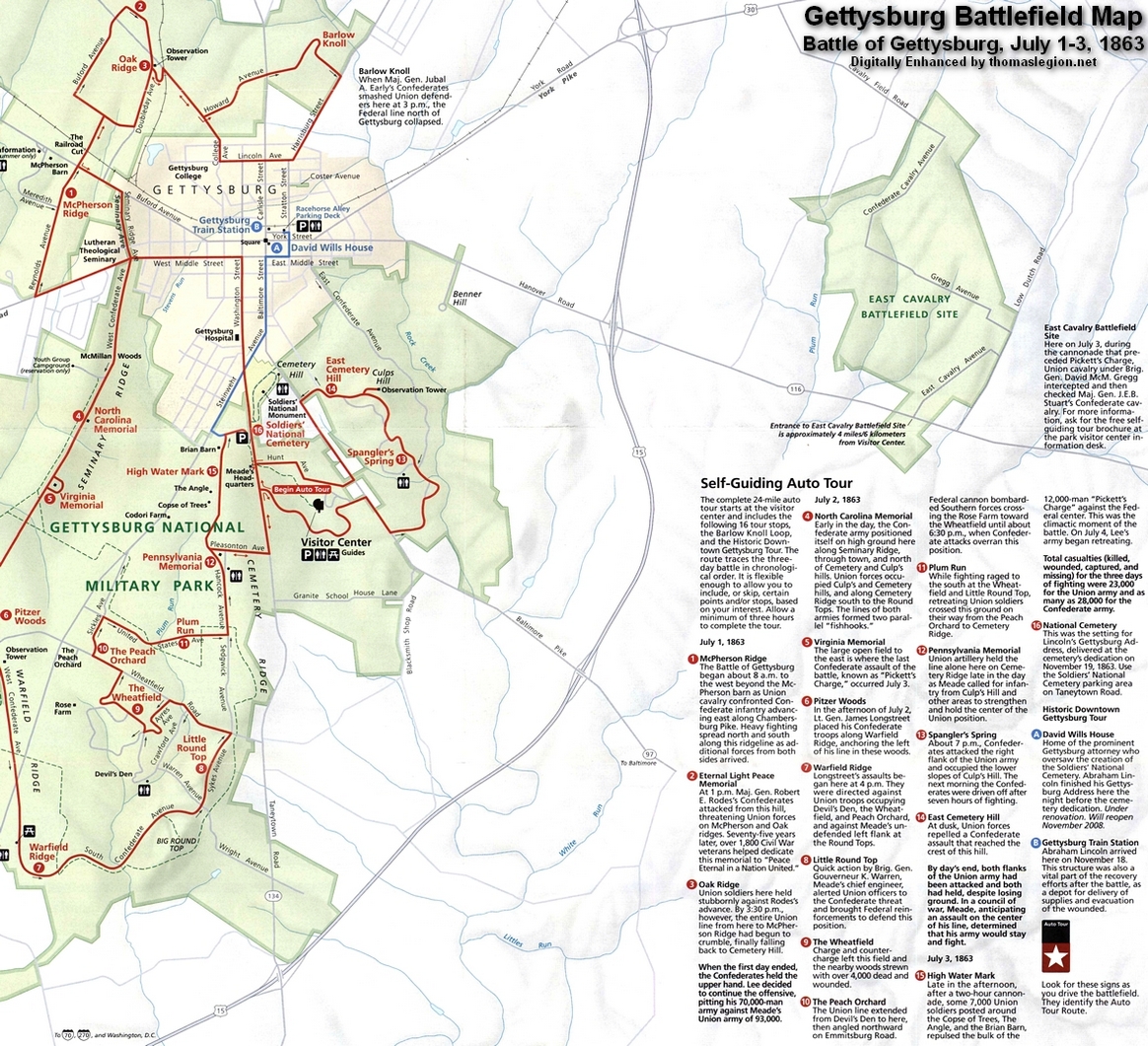

| Official Gettysburg Battlefield Tour Map |

| Spangler's Spring today |

|

| Gettysburg NMP |

Ewell began his demonstration at 4 p.m. upon hearing the sound of Longstreet's

guns to the south. For three hours, he chose to limit his demonstration to an artillery barrage from Benner's Hill, about

a mile to the northeast. But despite this demonstration, Ewell did not hold the attention of Army of the Potomac commander,

Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. Meade was occupied with the fierce fighting on his left flank and was scrambling to send as many

reinforcements as possible. He ordered Slocum to send the XII Corps in support. It is unclear whether he ordered the entire

corps or instructed Slocum to leave one brigade behind, but the latter is what Slocum did, and Greene's brigade was left with

the sole responsibility for defending Culp's Hill.

Greene extended his line to the right to cover part of the lower slope,

but his 1,400 men would be dangerously overextended if a Confederate attack came. They were only able to form a single battle

line, without reserves. Only three of the five brigades of Union troops that were dispatched from the hill saw combat. The

remainder of Geary's division marched down the Baltimore Pike and missed a key right hand turn. By the time they realized

where they were, the crisis on the Union left flank and center had subsided.

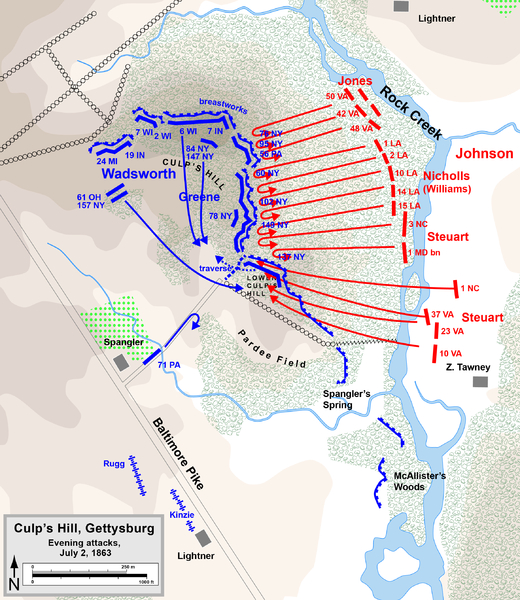

Around 7 p.m., as dusk began to fall, and the Confederate assaults on the

Union left and center were slowing, Ewell chose to begin his main infantry assault. He sent three brigades (4,700 men) from

the division of Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson across Rock Creek and up the eastern slope of Culp's Hill. The brigades

were, from left to right, those of Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart, Col. Jesse M. Williams (Nicholl's Brigade), and Brig. Gen.

John M. Jones. The Stonewall Brigade, under Brig. Gen. James A. Walker, was occupied with Union cavalry on Brinkerhoff's Ridge

to the rear.

As the fighting started, Greene sent for reinforcements from the I Corps and XI Corps to his left. Wadsworth

was able to send three regiments, and Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard on Cemetery Hill was able to send four—altogether 750

men, who served as Greene's reserve and help to restore dwindling supplies of ammunition.

On the Confederate right flank, Jones's brigade of Virginians had the most

difficult terrain to cross, the steepest part of Culp's Hill. As they scrambled through the woods and up the rocky slope,

they were shocked at the strength of the Union breastworks on the crest. Their charges were beaten off with relative ease

by the 60th New York, which suffered very few casualties. Confederate casualties were high, including General Jones, who was

wounded and left the field. One of the New York officers wrote "without breastworks our line would have been swept away in

an instant by the hailstorm of bullets and the flood of men."

| Battle of Spangler's Spring, Gettysburg |

|

| Battle of Spangler's Spring, July 2, 1863 |

| Battle of Spangler's Spring, Gettysburg |

|

| Battle of Spangler's Spring, July 2, 1863 |

In the center, Nicholls's Louisiana brigade had a similar experience to

Jones's. The attackers were essentially invisible in the dark except for brief instances when they fired, but the defensive

works were impressive, and the 78th and 102nd New York regiments suffered few casualties in a fight that lasted four hours.

Steuart's regiments on the left occupied the empty breastworks on the lower

hill and felt their way in the darkness toward Greene's right flank. The Union defenders waited nervously, watching as the

flashes of the Confederate rifles drew near. But as they approached, Greene's men delivered a withering fire. The 3rd North

Carolina "reeled and staggered like a drunken man."

Two regiments on Steuart's left, the 23rd and 10th Virginia, outflanked

the works of the 137th New York. Like the fabled 20th Maine of Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain on Little Round Top earlier that

afternoon, Col. David Ireland of the 137th New York found himself on the extreme end of the Union army, fending off a strong

flanking attack. Under heavy pressure, the New Yorkers were forced back to occupy a traversing trench that Greene had engineered

facing south. They essentially held their ground and protected the flank, but they lost almost a third of their men in doing

so. Because of the darkness and Greene's brigade's heroic defense, Steuart's men did not realize that they had almost unlimited

access to the main line of communication for the Union army, the Baltimore Pike, only 600 yards to their front. Ireland and

his men prevented a huge disaster from befalling Meade's army, although they never received the publicity that their colleagues

from Maine enjoyed.

In the confusion of fighting in the dark, the 1st North Carolina, brought

up from the reserves, fired on the Confederate 1st Maryland Battalion by mistake. (In Gettysburg National Military Park, the

monument to this battalion refers to the "2nd Maryland" so that it would not be confused with the two Union regiments named

1st Maryland in Lockwood's brigade.)

During the heat of the fighting, the sound of battle reached II Corps commander

Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock on Cemetery Ridge, who immediately sent additional reserve forces. The 71st Pennsylvania

filed in to assist the 137th New York on Greene's right.

By the time the rest of the XII Corps returned late that night, Confederate

troops had occupied some of the Union defensive line on the southeastern slope of the hill, near Spangler's Spring. This caused

considerable confusion as the Union troops stumbled in the dark to find enemy soldiers in the positions they had vacated.

Gen. Williams did not want to continue this confused fight, so he ordered his men to occupy the open field in front of the

woods and wait for daylight. And while Steuart's brigade maintained a fragile hold on the lower heights, Johnson's other two

brigades were pulled off the hill, also to wait for daylight. Geary's men returned to reinforce Greene. Both sides prepared

to attack at dawn, the third and final day of the engagement.

Sources: National Park Service; Gettysburg National Military Park; Civil

War Trust, civilwartrust.org; Hap Jespersen, cwmaps.com.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg--Culp's Hill

and Cemetery Hill (Civil War America)

(Hardcover). Description: In this companion to his

celebrated earlier book, Gettysburg—The Second Day, Harry Pfanz provides the first definitive

account of the fighting between the Army of the Potomac and Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Cemetery Hill and

Culp's Hill—two of the most critical engagements fought at Gettysburg

on 2 and 3 July 1863. Pfanz provides detailed tactical accounts of each stage of the

contest and explores the interactions between—and decisions made by—generals on both sides. In particular, he

illuminates Confederate lieutenant general Richard S. Ewell's controversial decision not to attack Cemetery Hill after the

initial southern victory on 1 July. Continued below...

Pfanz also

explores other salient features of the fighting, including the Confederate occupation of the town of Gettysburg,

the skirmishing in the south end of town and in front of the hills, the use of breastworks on Culp's Hill, and the small but

decisive fight between Union cavalry and the Stonewall Brigade. About the Author: Harry

W. Pfanz is author of Gettysburg--The First Day and Gettysburg--The

Second Day. A lieutenant, field artillery, during World War II, he served for ten years as a historian at Gettysburg National

Military Park and retired from the position of Chief Historian of the National Park Service in 1981. To purchase additional

books from Pfanz, a convenient Amazon Search Box is provided at the bottom

of this page.

Recommended Reading: The Artillery

of Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: The battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the apex of the Confederacy's final major invasion of the North,

was a devastating defeat that also marked the end of the South's offensive strategy against the North. From this battle until

the end of the war, the Confederate armies largely remained defensive. The Artillery of Gettysburg is a thought-provoking

look at the role of the artillery during the July 1-3, 1863 conflict. Continued below...

During the

Gettysburg

campaign, artillery had already gained the respect in both armies. Used defensively, it could break up attacking formations

and change the outcomes of battle. On the offense, it could soften up enemy positions prior to attack. And even if the results

were not immediately obvious, the psychological effects to strong artillery support could bolster the infantry and discourage

the enemy. Ultimately, infantry and artillery branches became codependent, for the artillery needed infantry support lest

it be decimated by enemy infantry or captured. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had modified its codependent command

system in February 1863. Prior to that, batteries were allocated to brigades, but now they were assigned to each infantry

division, thus decentralizing its command structure and making it more difficult for Gen. Robert E. Lee and his artillery

chief, Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, to control their deployment on the battlefield. The Union Army of the Potomac

had superior artillery capabilities in numerous ways. At Gettysburg,

the Federal artillery had 372 cannons and the Confederates 283. To make matters worse, the Confederate artillery frequently

was hindered by the quality of the fuses, which caused the shells to explode too early, too late, or not at all. When combined

with a command structure that gave Union Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt more direct control--than his Southern counterpart had over

his forces--the Federal army enjoyed a decided advantage in the countryside around Gettysburg. Bradley

M. Gottfried provides insight into how the two armies employed their artillery, how the different kinds of weapons functioned

in battle, and the strategies for using each of them. He shows how artillery affected the “ebb and flow” of battle

for both armies and thus provides a unique way of understanding the strategies of the Federal and Union

commanders.

Recommended Reading: The History

Buff's Guide to Gettysburg (Key People, Places, and Events)

(Key People, Places, and Events). Description: While most history books are dry monologues of people, places, events and dates,

The History Buff's Guide is ingeniously written and full of not only first-person accounts but crafty prose. For example,

in introducing the major commanders, the authors basically call Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell a chicken literally.

Continued

below...

'Bald, bug-eyed,

beak-nosed Dick Stoddard Ewell had all the aesthetic charm of a flightless foul.' To balance things back out a few pages later,

they say federal Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade looked like a 'brooding gargoyle with an intense cold stare, an image in perfect

step with his nature.' Although it's called a guide to Gettysburg, in my opinion, it's an authoritative guide to

the Civil War. Any history buff or Civil War enthusiast or even that casual reader should pick it up.

Recommended Reading: The Maps of Gettysburg: The Gettysburg

Campaign, June 3 - July 13, 1863 (Hardcover). Description: More academic and photographic accounts on the battle of Gettysburg

exist than for all other battles of the Civil War combined-and for good reason. The three-days of maneuver, attack,

and counterattack consisted of literally scores of encounters, from corps-size actions to small unit engagements. Despite

all its coverage, Gettysburg remains one of the most complex

and difficult to understand battles of the war. Author Bradley Gottfried offers a unique approach to the study of this multifaceted

engagement. The Maps of Gettysburg plows new ground in the study of the campaign by breaking down the entire campaign in 140

detailed original maps. These cartographic originals bore down to the regimental level, and offer Civil Warriors a unique

and fascinating approach to studying the always climactic battle of the war. Continued below...

The Maps of

Gettysburg offers thirty "action-sections" comprising the entire campaign. These include the march to and from the battlefield,

and virtually every significant event in between. Gottfried's original maps further enrich each "action-section." Keyed to

each piece of cartography is detailed text that includes hundreds of soldiers' quotes that make the Gettysburg

story come alive. This presentation allows readers to easily and quickly find a map and text on virtually any portion of the

campaign, from the great cavalry clash at Brandy Station on June 9, to the last Confederate withdrawal of troops across the

Potomac River on July 15, 1863. Serious students of the battle will appreciate the extensive

and authoritative endnotes. They will also want to bring the book along on their trips to the battlefield… Perfect for

the easy chair or for stomping the hallowed ground of Gettysburg,

The Maps of Gettysburg promises to be a seminal work that belongs on the bookshelf of every serious and casual student of

the battle.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg, by Stephen W. Sears (640 pages)

(November 3, 2004). Description: Sears delivers another

masterpiece with this comprehensive study of America’s

most studied Civil War battle. Beginning with Lee's meeting with Davis

in May 1863, where he argued in favor of marching north, to take pressure off both Vicksburg

and Confederate logistics. It ends with the battered Army of Northern Virginia re-crossing the Potomac just two months later

and with Meade unwilling to drive his equally battered Army of the Potomac into a desperate

pursuit. In between is the balanced, clear and detailed story of how tens-of-thousands of men became casualties, and how Confederate

independence on that battlefield was put forever out of reach. The author is fair and balanced. Continued below...

He discusses

the shortcomings of Dan Sickles, who advanced against orders on the second day; Oliver Howard, whose Corps broke and was routed

on the first day; and Richard Ewell, who decided not to take Culp's Hill on the first night, when that might have been decisive.

Sears also makes a strong argument that Lee was not fully in control of his army on the march or in the battle, a view conceived

in his gripping narrative of Pickett's Charge, which makes many aspects of that nightmare much clearer than previous studies.

A must have for the Civil War buff and anyone remotely interested in American history.

Recommended Reading: The Gettysburg

Campaign: A Study in Command (928 pages). Description: Coddington's

research is one of the most thorough and detailed studies of the Gettysburg Campaign. Exhaustive in scope and scale, Coddington

delivers, with unrivaled research, in-depth battle descriptions and a complete history of the regiments involved. Continued

below...

This

is a must read for anyone seriously interested in American history and what transpired and shaped a nation on those pivotal

days in July 1863.

Recommended Reading: ONE CONTINUOUS

FIGHT: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee's Army of Northern

Virginia, July 4-14, 1863 (Hardcover) (June 2008). Description: The titanic three-day battle of Gettysburg

left 50,000 casualties in its wake, a battered Southern army far from its base of supplies, and a rich historiographic legacy.

Thousands of books and articles cover nearly every aspect of the battle, but not a single volume focuses on the military aspects

of the monumentally important movements of the armies to and across the Potomac River. One

Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit

of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, July 4-14, 1863 is the first detailed military history of Lee's retreat and the Union

effort to catch and destroy the wounded Army of Northern Virginia. Against steep odds and encumbered with thousands of casualties,

Confederate commander Robert E. Lee's post-battle task was to successfully withdraw his army across the Potomac River. Union

commander George G. Meade's equally difficult assignment was to intercept the effort and destroy his enemy. The responsibility

for defending the exposed Southern columns belonged to cavalry chieftain James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart. If Stuart fumbled

his famous ride north to Gettysburg, his generalship during

the retreat more than redeemed his flagging reputation. The ten days of retreat triggered nearly two dozen skirmishes and

major engagements, including fighting at Granite Hill, Monterey Pass,

Hagerstown, Williamsport, Funkstown,

Boonsboro, and Falling Waters. Continued

below...

President Abraham

Lincoln was thankful for the early July battlefield victory, but disappointed that General Meade was unable to surround and

crush the Confederates before they found safety on the far side of the Potomac. Exactly what Meade did to try to intercept the fleeing Confederates, and how the

Southerners managed to defend their army and ponderous 17-mile long wagon train of wounded until crossing into western Virginia on the early morning of July 14, is the subject of this study.

One Continuous Fight draws upon a massive array of documents, letters, diaries, newspaper accounts, and published primary

and secondary sources. These long-ignored foundational sources allow the authors, each widely known for their expertise in

Civil War cavalry operations, to describe carefully each engagement. The result is a rich and comprehensive study loaded with

incisive tactical commentary, new perspectives on the strategic role of the Southern and Northern cavalry, and fresh insights

on every engagement, large and small, fought during the retreat. The retreat from Gettysburg

was so punctuated with fighting that a soldier felt compelled to describe it as "One Continuous Fight." Until now, few students

fully realized the accuracy of that description. Complimented with 18 original maps, dozens of photos, and a complete driving

tour with GPS coordinates of the entire retreat, One Continuous Fight is an essential book for every student of the American

Civil War in general, and for the student of Gettysburg in

particular. About the Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg has written widely on Civil War cavalry operations. His books include Glory

Enough for All (2002), The Union Cavalry Comes of Age (2003), and The Battle of Monroe's Crossroads and the Civil War's Final

Campaign (2005). He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

J. David Petruzzi is the author of several magazine articles on Eastern Theater cavalry operations, conducts tours of cavalry

sites of the Gettysburg Campaign, and is the author of the popular "Buford's Boys." A long time student of the Gettysburg

Campaign, Michael Nugent is a retired US Army Armored Cavalry Officer and the descendant of a Civil War Cavalry soldier. He

has previously written for several military publications. Nugent lives in Wells, Maine.

|