|

Trostle Farm and Plum Run

Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Plum Run Trostle Farm Battle of Gettysburg, Emmitsburg Road The Wheatfield Battlefield, General Daniel

Sickles Third Corps Army of the Potomac, General Sickles Devil's Den, The Peach Orchard Cemetery Ridge

Trostle Farm, Plum Run, and Battle of Gettysburg

Summary

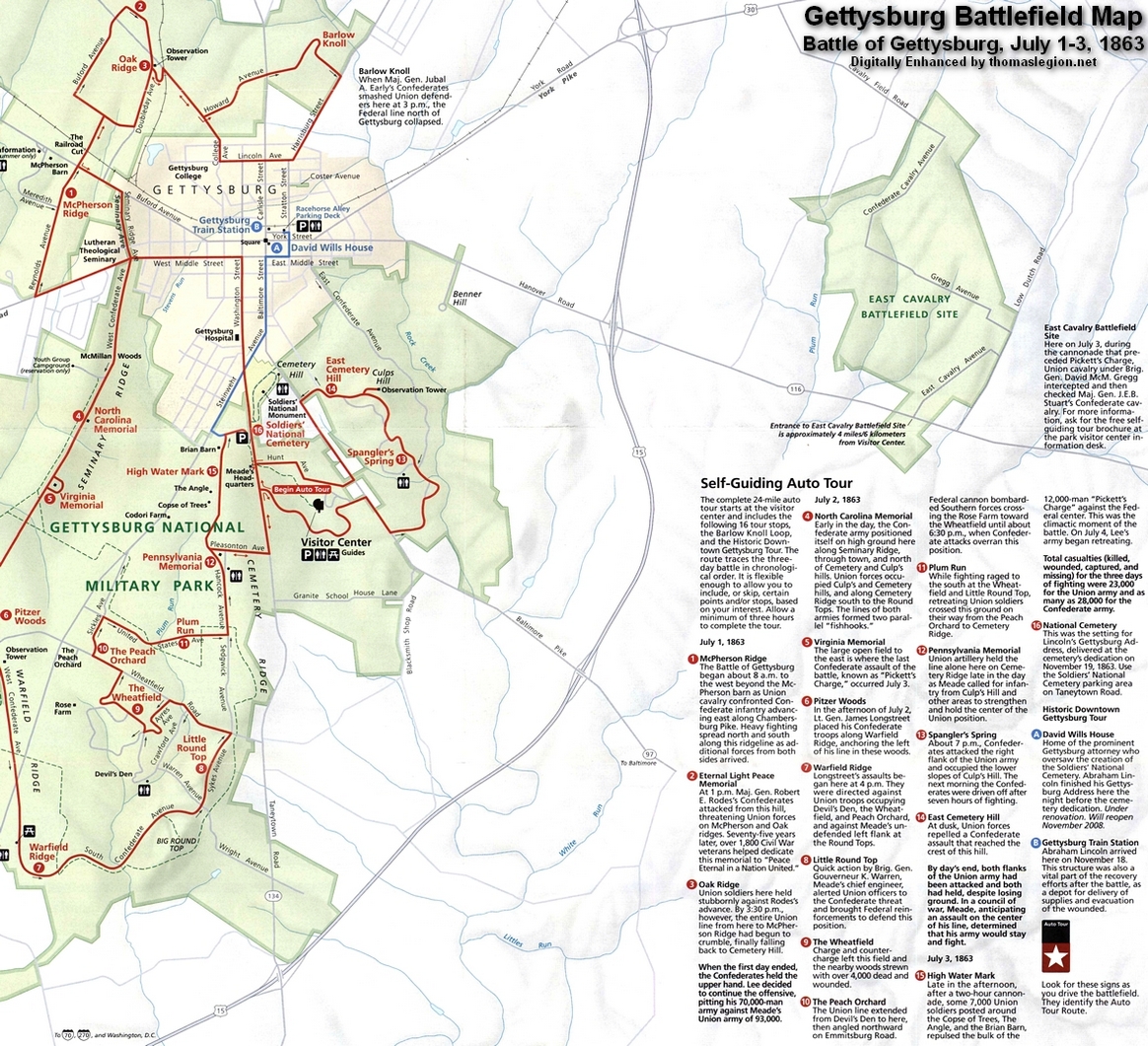

The second day’s battle of Gettysburg was the largest and costliest of the three days. The second

day’s fighting (at Devil’s Den, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, Cemetery Ridge, Trostle Farm,

Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill) involved at least 100,000 soldiers of which roughly 20,000 were killed, wounded, captured

or missing. The second day in itself ranks as the 10th bloodiest battle of the Civil War.

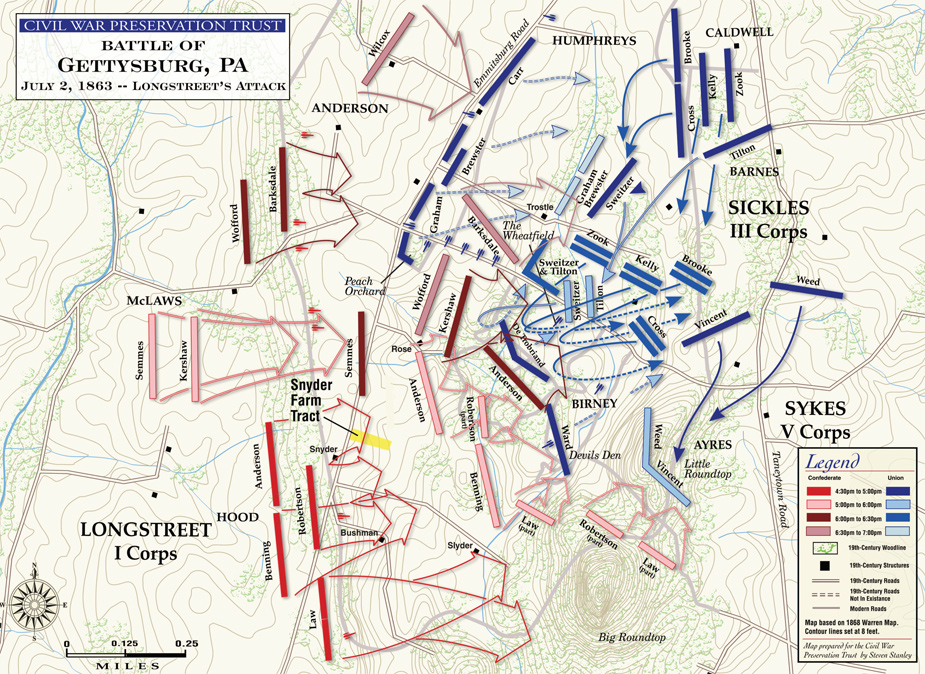

While the right wing of Kershaw's brigade attacked into the Wheatfield,

its left wing wheeled left to attack the Pennsylvania troops in the brigade of Brig. Gen. Charles K. Graham, the right flank

of Birney's line, where 30 guns from the III Corps and the Artillery Reserve attempted to hold the sector. The South Carolinians

were subjected to infantry volleys from the Peach Orchard and canister from all along the line. Suddenly someone unknown shouted

a false command, and the attacking regiments turned to their right, toward the Wheatfield, which presented their left flank

to the batteries. Kershaw later wrote, "Hundreds of the bravest and best men of Carolina fell, victims of this fatal blunder."

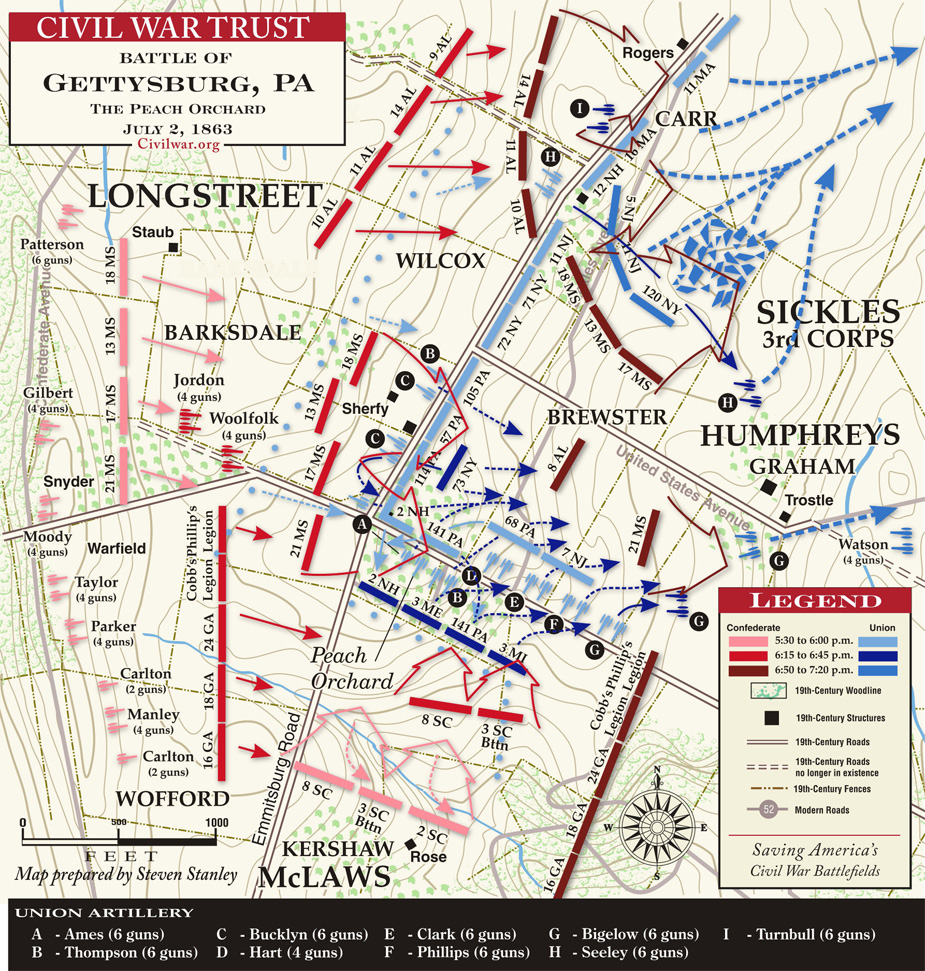

Meanwhile, the two brigades on McLaws's left—Barksdale's in front

and Wofford's behind—charged directly into the Peach Orchard, the point of the salient in Sickles's line. Gen. Barksdale

led the charge on horseback, long hair flowing in the wind, sword waving in the air. Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys's division

had only about 1,000 men to cover the 500 yards from the Peach Orchard northward along the Emmitsburg Road to the lane leading

to the Abraham Trostle farm. Some were still facing south, from where they had been firing on Kershaw's brigade, so they were

hit in their vulnerable flank. Barksdale's 1,600 Mississippians wheeled left against the flank of Humphreys's division, collapsing

their line, regiment by regiment. Graham's brigade retreated back toward Cemetery Ridge; Graham had two horses shot out from

under him. He was hit by a shell fragment, and by a bullet in his upper body. He was eventually captured by the 21st Mississippi.

Wofford's men dealt with the defenders of the orchard.

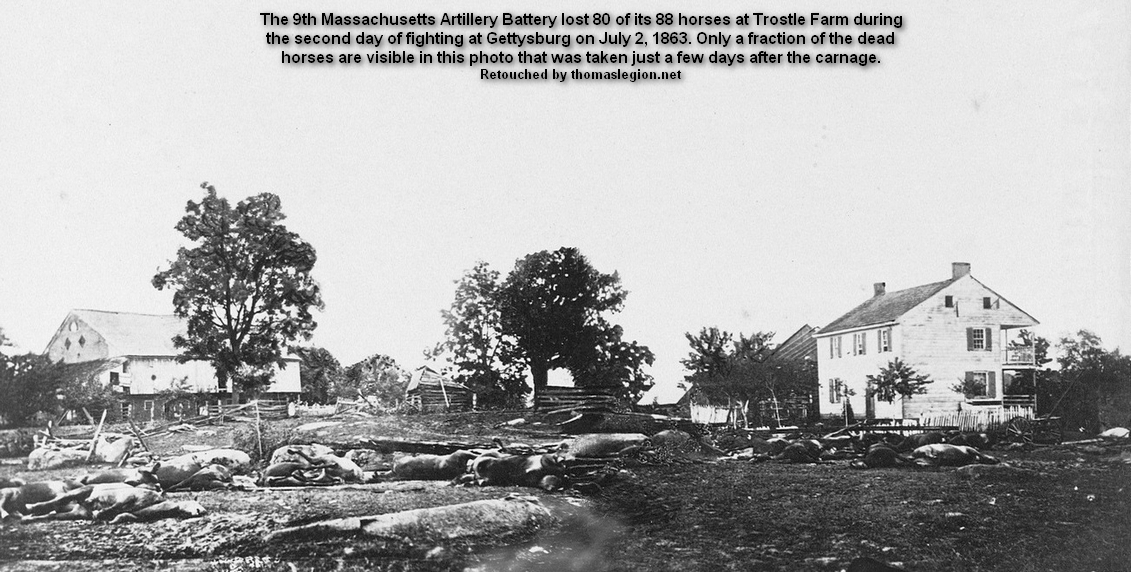

| Horses killed during fight at Trostle Farm |

|

| "80 dead horses at Trostle Farm during Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863" |

(About) The 9th Massachusetts Battery suffered 80 dead horses during the fight at Trostle,

July 2nd, 1863, at Gettysburg. The Battle of Gettysburg, like the majority of Civil War battles, raged over the private

property of ordinary farmers and citizens. The buildings on these properties, if they were not destroyed, were often

converted into field hospitals to treat wounded and dying soldiers. On the Trostle homestead, July 2, 1863, as waves

of gray-clad men continued to press its front, the 9th Massachusetts, now engaged in a very deadly contest,

was ordered to fire double-canister at the advancing Confederates. As canister cracked and peppered the field, the

gray wave, not faltering, had pushed through the dense smoke and closed the already shortened field between

the foe. Too late to limber and move the artillery, understood the Union men, who were now facing superior numbers without their equalizers of canister and shot. On

the Confederate side, the sounds of cold steel rattling and clanking could be heard as some of the men had transitioned

to fixed bayonets. "Shoot the horses!" shouted one soldier of the 21st Mississippi Infantry, and the animals fell

in heaps still strapped to their harnesses. Passing enemy cannon muzzles the Rebels were met with determined artillerymen

who fought back with hand spikes, rammers, pistols, and fists. "We fought with our guns until the rebs put their hands

on (them)," wrote Private David Brett. "The bullets flew thick as hailstones... It is a mericle(sic) that we were not all

killed." The survivors finally fled, leaving behind guns, limbers, and the wounded and dead intermingled with the dead and

dying horses. The first battle experience of the 9th Massachusetts Battery had ended in a bloody disaster. The battery suffered 80 of its 88 horses in killed, and the fallen equines

covered every portion of the Trostle yard.

As Barksdale's men pushed toward Sickles's headquarters near the Trostle

barn, the general and his staff began to move to the rear, when a cannonball caught Sickles in the right leg. He was carried

off in a stretcher, sitting up and puffing on his cigar, attempting to encourage his men. That evening his leg was amputated,

and he returned to Washington, D.C. Gen. Birney assumed command of the III Corps, which was soon rendered ineffective as a

fighting force.

The relentless infantry charges posed extreme danger to the Union artillery

batteries in the orchard and on the Wheatfield Road, and they were forced to withdraw under pressure. The six Napoleons of

Capt. John Bigelow's 9th Massachusetts battery, on the left of the line, "retired by prolonge," a technique rarely used in

which the cannon was dragged backwards as it fired rapidly, the movement aided by the gun's recoil. By the time they reach

the Trostle house, they were told to hold the position to cover the infantry retreat, but they were eventually overrun by

troops of the 21st Mississippi, who captured three of their guns.

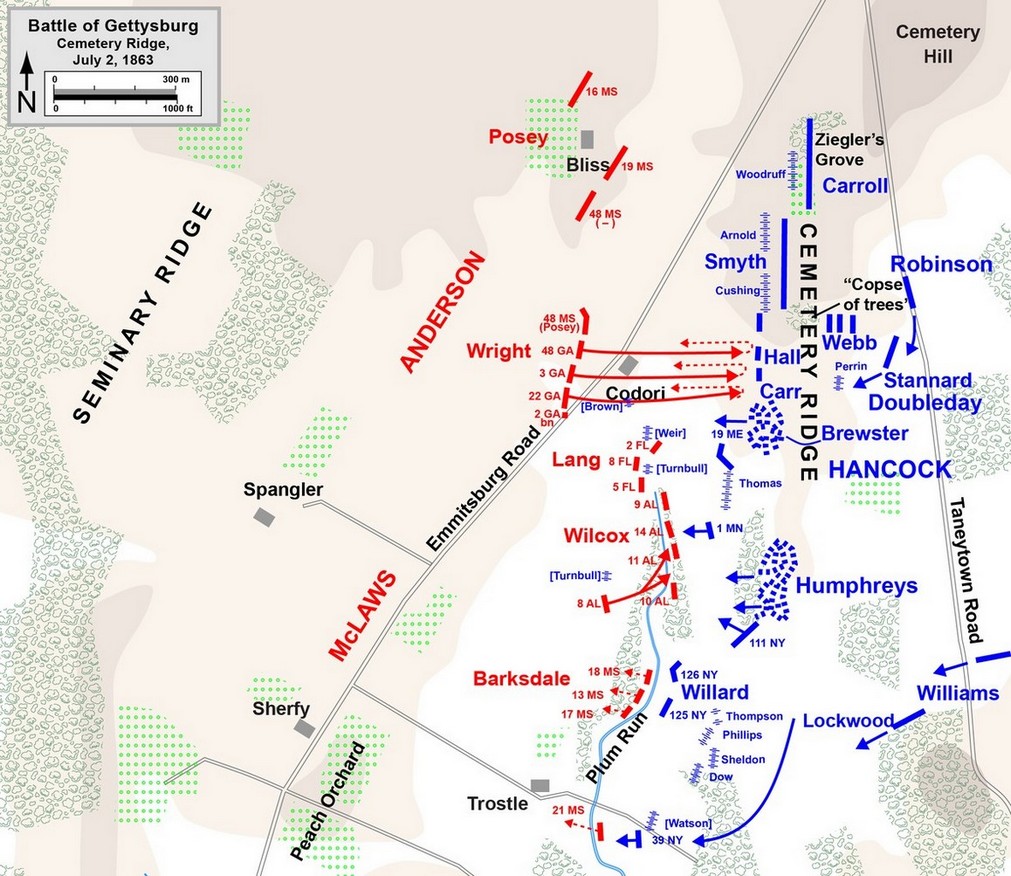

Humphreys's fate was sealed when the Confederate en echelon attack continued

and his front and right flank began to be assaulted by the Third Corps division of Richard H. Anderson on Cemetery Ridge.

| Plum Run, Trostle Farm, and Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Trostle Farm, Plum Run, and Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

History

| The Abraham Trostle Farm House |

|

| Gettysburg NMP |

Just west of a narrow, slow moving stream called Plum Run is the Abraham Trostle Farm, one of the larger

and more prosperous farms on the battlefield. Trostle owned most of the land bordering Plum Run to the east, the Emmitsburg

Road to the west, and Wheatfield Road to the south, the two roads along which General Sickles had formed his Third Corps on

the afternoon of July 2, 1863. Prosperity of Trostle's farm was reflected in the buildings he owned which included a large

Pennsylvania-style bank barn with a wagon shed addition, and a new, wood frame house. In the summer of 1863, Trostle was busy

dismantling an earlier log house and constructing a large brick summer kitchen. An expansive apple orchard adjacent to the

house provided the family with an abundance of fruit and Trostle's rich fields yielded an excellent harvest of corn, rye and

wheat. Like most battlefield families, the Trostle's lives were forever changed by the battle and most of their property was

lost or destroyed.

| Gen. Sickles |

|

| National Archives |

| Capt. Bigelow |

|

| USAMHI |

Warned by Union staff officers of the impending danger right at their doorstep, the family abandoned their

home on July 2. After moving a part of his Third Corps out to the Peach Orchard from Cemetery Ridge, General Sickles established his headquarters in the yard of the house and waited for the arrival of General

Meade while his staff officers helped themselves to the remains of the noon day meal left behind on the dining room table.

General Sickles' advanced battle line stretched from Devil's Den to the Peach Orchard, and then northward on the Emmitsburg Road- a very wide area to cover and Sickles barely

had enough troops to do so. Once the Confederate attack had begun at 4 o'clock and Meade ordered Sickles to keep his troops where they were so that they could be reenforced, the general remained in

the Trostle yard where he passed orders to shore up the weaker parts of his line and hurry forward reinforcements from other

commands as they arrived on the field. Confederate artillery zeroed in on Sickles' line and shots that missed the front fell

around the headquarters group. Iron fragments from shell bursts clipped branches from the trees and rattled against the stone

walls of the nearby barn as orderlies rushed to and fro.

| Battle of Gettysburg July 2, 1863 |

|

| Trostle Farm and Plum Run, Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

| The Trostle Farm |

|

| Gettysburg NMP |

(Left) Picture of the Trostle Farm from Wheatfield Road. The 9th Massachusetts

Battery retreated over this field to the farm buildings. Gettysburg NMP.

At the height of the battle, Sickles was mounted on his horse watching the

battle when he seriously wounded by a Confederate shell. Pale and in shock, the general was helped down from his horse by

aides who saw that one of Sickles' legs had been crushed by the shell. Placed on a stretcher and carried back to the Union

rear in terrible pain, the daunting officer was not to be outdone. Sickles ordered his bearers to halt while he gathered his

wits, propped himself up on his stretcher and asked one of his orderlies to light a cigar for him. Countless Union soldiers

marching toward the sound of battle encountered the general on his stretcher, calmly smoking his cigar and saluting them with

a wave of his hat as he was carried along the Baltimore Pike- an inspiring sight to those who about to go into battle. The

shattered leg was removed by an army surgeon later that evening and General Sickles' career as a corps commander was over.

Unaware of the impending crisis at

the Peach Orchard, Major General David Birney was seeing to his battered units near the Wheatfield when a staff officer informed

him that he was now the commander of the Third Corps. By this time, the Union line was in great disarray and under attack

all along its front. As the Confederate pressure mounted and the position at the Peach Orchard collapsed, retreating Union

troops streamed through the Trostle farm toward Cemetery Ridge.

| 9th Massachusetts Battery |

|

| Gettysburg NMP |

(Right) Monument to the 9th Massachusetts Battery at the Trostle Farm,

site of the battery's last stand. Photograph Gettysburg NMP.

A narrow farm lane that ran east to west beside the Trostle buildings was used by Union artillery to reach

positions near the Peach Orchard, and retreating artillerymen galloped their horses and guns back down the same lane to make

their way toward Cemetery Ridge. Most of the Union batteries made it except for the rookie 9th Massachusetts Battery, commanded by Captain John Bigelow. Bigelow's soldiers were in the first real battle they had ever experienced

and fought throughout the afternoon like veterans. After retiring to the Trostle buildings from the Wheatfield Road, Bigelow

was ordered to hold until a new artillery line could be formed on Cemetery Ridge. The men unlimbered the guns, loaded, and

grimly waited for the converging ranks of Southerners to get closer. "The enemy approached over the knoll," Bigelow reported,

"Waiting till they were breast high, my battery discharged... double-shotted canister and solid shot. Through the smoke (I)

caught a glimpse of the enemy... torn and broken, but still advancing."

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

|

| Trostle Farm and Plum Run, Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

(Right) Photo of field north of the Trostle buildings where General Barksdale

was discovered by Union soldiers after nightfall. Cemetery Ridge is in the distance. Gettysburg NMP.

Bigelow's gunners kept up a steady fire, keeping the Confederates at a respectful distance until orders

to withdraw finally arrived. Quickly the men limbered the guns. The first gun team rushed toward the single gate near the

house and had almost made it through when a wheel caught one of the posts, upsetting the gun in the gateway and blocking it.

Men rushed to unright the heavy gun and open the lane, but the battery was trapped, surrounded by stout fences and stone walls.

Bigelow ordered his gunners to unlimber again and reload with canister. Just as the first rounds were rammed home, the 21st

Mississippi Infantry broke through the dense smoke and pounced on the battery, shooting and cursing. Above the din, someone

shouted, "Shoot the horses!" and the animals fell in heaps still strapped to their harnesses. The artillerymen fought back

with hand spikes, rammers, pistols, and fists. "We fought with our guns until the rebs put their hands on (them)," wrote Private

David Brett. "The bullets flew thick as hailstones... It is a mericle(sic) that we were not all killed." The survivors finally

fled, leaving behind guns, limbers, and the wounded and dead intermingled with the dead and dying horses. The first battle

experience of the 9th Massachusetts Battery had ended in a bloody disaster. See also

Life of a Civil War Horse and Civil War Horses of the Union and Confederate Armies.

| Gen. Barksdale |

|

| Generals in Gray |

A granite replica of a limber chest marks the spot where the 9th Massachusetts

Battery fought by the Trostle farm buildings on that hot afternoon. Veterans of the battery chose this particular design,

which readily identifies them as an artillery unit. The five guns lost to the 21st Mississippi Infantry were later recaptured

by Union troops of the 150th New York Infantry and with their recovered guns, the 9th Massachusetts Battery was back in action

the following day.

| Second Day, Batte of Gettysburg |

|

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

The victorious Mississippians swept past the Trostle buildings toward Cemetery

Ridge. As they splashed across Plum Run, an officer spied another Union battery (I, 5th US) unlimbering their guns on a knoll

100 yards ahead. With little encouragement, the soldiers rushed headlong toward it, shooting and clubbing the surprised artillerymen

before they could even load the guns. The others scattered including the drivers who took the horse teams with them to deprive

the Southerners an easy way to remove the guns.

Though the 21st Mississippi had successfully reached the now open Union

center, their comrades in General Barksdale's brigade were still behind them, stalled along Plum Run, exhausted and disorganized.

If they moved quickly enough the Union line would be cut in two, but the

worn out Mississippians remained in the cover of Plum Run despite pleas and threats from the fiery Barksdale. Union reinforcements

soon arrived and charged into the valley, driving out those men who sought refuge along Plum Run. One soldier recalled passing

Barksdale, leaning against his horse pale and weak- blood showed on his chest and left boot, torn and bloodied by a cannon

shot. In the confusion that followed, the general was left behind on the battlefield.

Late that evening a detail from the 14th Vermont Infantry discovered Barksdale

and carried him to a Union hospital where his wounds were pronounced mortal. "I have never regretted the steps I have taken,"

he told one of his rescuers. "I do not regret my steps now, although it is hard to leave friends, wife and children. I do

not regret giving my life in a cause that I believe to be right. May God watch over and care for my dear wife, and oh, my

boys... may God be a father to them." These sentiments for his family were his last. Curious Union soldiers stopped to gawk

at the lifeless form of the famous general and politician while others stripped buttons, gold lace and collar insignia from

his uniform as souvenirs. Buried at the site where he died, the general's remains were moved after the war to Greenwood Cemetery

in Jackson, Mississippi, and it was not long after that Union veterans returned a number of items taken from the body to the

Barksdale family, including his collar insignia.

While Barksdale attempted to reignite his charge, the Confederate brigades

of General Cadmus Wilcox and Colonel Edward Perry descended into Plum Run, their attack driving toward the still open Union

center manned only by a handful of artillerymen and one lone Union regiment. Cemetery Ridge, which is your next stop, was

sure to fall.

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

|

| Trostle Farm and Plum Run, Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

The only known photographs of Union dead at Gettysburg

(Left) Picture of Union soldiers, possibly from the New York Excelsior

Brigade, lie in death where they last stood in line of battle on July 2. National Archives.

Some of heaviest fighting of the second day occurred on the Abraham Trostle

farm. Night time brought a new horror. Scattered about the woods and fields were the helpless wounded whose pitiful groans

and cries for help filled the night air, only fading away as the more seriously wounded expired.

Some of those cries may have come from this group of Union dead, possibly

located in a pasture north of the Trostle buildings. These men, most likely members of Colonel Brewster's "Excelsior Brigade",

lie scattered on a slight elevation where Wilcox's Alabama and Barksdale's Mississippi regiments slashed into their ranks.

(Right) Third photograph taken of the group. Other bodies can be seen scattered

in the far distance, marking the battleline. National Archives.

On July 5, 1863, Alexander Gardner and his team of photographers arrived

at Gettysburg and spent the following days photographing the battlefield. Spying this group on the Trostle farm, Gardner's

assistants made three exposures of this group, the only known photographs of Union dead on the Gettysburg battlefield. The

most knowledgeable authority on early photography at Gettysburg is historian and author William Frassanito who has produced

two monumental works, Gettysburg: A Journey in Time and Early Photography at Gettysburg. Even with his meticulous

research, he has confessed his inability to pinpoint the exact location of this horrid scene; but theorized that the photos

were taken somewhere on the southern end of the battlefield and probably in the Trostle or Rose Farm areas. Yet to this day,

the exact location on the Gettysburg battlefield where these photographs were taken is unknown. The final disposition of these

bodies is unknown, but it is likely that they rest today in the New York section of the Soldiers National Cemetery at Gettysburg.

Sources: National Park Service; Gettysburg National Military Park; Civil

War Trust, civilwar.org.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg--The Second Day, by Harry W. Pfanz (624 pages). Description: The second day's

fighting at Gettysburg—the assault of the Army of Northern Virginia against the Army

of the Potomac on 2 July 1863—was probably the critical engagement of that decisive

battle and, therefore, among the most significant actions of the Civil War. Harry Pfanz, a former historian at Gettysburg National Military Park, has written a definitive account

of the second day's brutal combat. He begins by introducing the men and units that were to do battle, analyzing the strategic

intentions of Lee and Meade as commanders of the opposing armies, and describing the concentration of forces in the area around

Gettysburg. He then examines the development of tactical plans

and the deployment of troops for the approaching battle. But the emphasis is on the fighting itself. Pfanz provides a thorough

account of the Confederates' smashing assaults—at Devil's Den and Little Round Top, through the Wheatfield and the Peach

Orchard, and against the Union center at Cemetery Ridge. He also details the Union defense that eventually succeeded in beating

back these assaults, depriving Lee's gallant army of victory. Continued below...

Pfanz analyzes decisions and events

that have sparked debate for more than a century. In particular he discusses factors underlying the Meade-Sickles controversy

and the questions about Longstreet's delay in attacking the Union left. The narrative is also enhanced by thirteen superb maps, more than eighty illustrations,

brief portraits of the leading commanders, and observations on artillery, weapons, and tactics that will be of help even to

knowledgeable readers. Gettysburg—The Second Day

is certain to become a Civil War classic. What makes the work so authoritative is Pfanz's mastery of the Gettysburg literature and his unparalleled knowledge of the ground on which the fighting

occurred. His sources include the Official Records, regimental histories and personal reminiscences from soldiers North and

South, personal papers and diaries, newspaper files, and last—but assuredly not least—the Gettysburg battlefield.

Pfanz's career in the National Park Service included a ten-year assignment as a park historian at Gettysburg. Without doubt, he knows the terrain of the battle as well as he knows the battle

itself

Recommended Reading: The Artillery

of Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: The battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the apex of the Confederacy's final major invasion of the North,

was a devastating defeat that also marked the end of the South's offensive strategy against the North. From this battle until

the end of the war, the Confederate armies largely remained defensive. The Artillery of Gettysburg is a thought-provoking

look at the role of the artillery during the July 1-3, 1863 conflict. Continued below...

During the

Gettysburg

campaign, artillery had already gained the respect in both armies. Used defensively, it could break up attacking formations

and change the outcomes of battle. On the offense, it could soften up enemy positions prior to attack. And even if the results

were not immediately obvious, the psychological effects to strong artillery support could bolster the infantry and discourage

the enemy. Ultimately, infantry and artillery branches became codependent, for the artillery needed infantry support lest

it be decimated by enemy infantry or captured. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had modified its codependent command

system in February 1863. Prior to that, batteries were allocated to brigades, but now they were assigned to each infantry

division, thus decentralizing its command structure and making it more difficult for Gen. Robert E. Lee and his artillery

chief, Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, to control their deployment on the battlefield. The Union Army of the Potomac had superior artillery capabilities

in numerous ways. At Gettysburg, the Federal artillery had

372 cannons and the Confederates 283. To make matters worse, the Confederate artillery frequently was hindered by the quality

of the fuses, which caused the shells to explode too early, too late, or not at all. When combined with a command structure

that gave Union Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt more direct control--than his Southern counterpart had over his forces--the Federal

army enjoyed a decided advantage in the countryside around Gettysburg. Bradley

M. Gottfried provides insight into how the two armies employed their artillery, how the different kinds of weapons functioned

in battle, and the strategies for using each of them. He shows how artillery affected the “ebb and flow” of battle

for both armies and thus provides a unique way of understanding the strategies of the Federal and Union

commanders.

Recommended Reading: The History

Buff's Guide to Gettysburg (Key People, Places, and Events)

(Key People, Places, and Events). Description: While most history books are dry monologues of people, places, events and dates,

The History Buff's Guide is ingeniously written and full of not only first-person accounts but crafty prose. For example,

in introducing the major commanders, the authors basically call Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell a chicken literally.

Continued

below...

'Bald, bug-eyed,

beak-nosed Dick Stoddard Ewell had all the aesthetic charm of a flightless foul.' To balance things back out a few pages later,

they say federal Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade looked like a 'brooding gargoyle with an intense cold stare, an image in perfect

step with his nature.' Although it's called a guide

to Gettysburg,

in my opinion, it's an authoritative guide to the Civil War. Any history buff or Civil War enthusiast or even that casual

reader should pick it up.

Recommended

Reading: The Maps of Gettysburg:

The Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 - July 13, 1863

(Hardcover). Description: More academic and photographic

accounts on the battle of Gettysburg exist than for all other

battles of the Civil War combined-and for good reason. The three-days of maneuver, attack, and counterattack consisted of

literally scores of encounters, from corps-size actions to small unit engagements. Despite all its coverage, Gettysburg remains one of the most complex and difficult to understand battles of the war.

Author Bradley Gottfried offers a unique approach to the study of this multifaceted engagement. Continued below...

The Maps of

Gettysburg plows new ground in the study of the campaign by breaking down the entire campaign in 140 detailed original maps.

These cartographic originals bore down to the regimental level, and offer Civil Warriors a unique and fascinating approach

to studying the always climactic battle of the war. The Maps of Gettysburg offers thirty "action-sections" comprising the

entire campaign. These include the march to and from the battlefield, and virtually every significant event in between. Gottfried's

original maps further enrich each "action-section." Keyed to each piece of cartography is detailed text that includes hundreds

of soldiers' quotes that make the Gettysburg story come alive. This presentation allows readers to easily

and quickly find a map and text on virtually any portion of the campaign, from the great cavalry clash at Brandy Station on

June 9, to the last Confederate withdrawal of troops across the Potomac River on July 15,

1863. Serious students of the battle will appreciate the extensive and authoritative endnotes. They will also want to bring

the book along on their trips to the battlefield… Perfect for the easy chair or for stomping the hallowed ground of

Gettysburg, The Maps of Gettysburg promises to be a seminal

work that belongs on the bookshelf of every serious and casual student of the battle.

Recommended

Reading: Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. Description: America's Civil War raged for more than four years, but it is the three days of fighting in the Pennsylvania countryside in July 1863 that continues to fascinate,

appall, and inspire new generations with its unparalleled saga of sacrifice and courage. From Chancellorsville, where General

Robert E. Lee launched his high-risk campaign into the North, to the Confederates' last daring and ultimately-doomed act,

forever known as Pickett's Charge, the battle of Gettysburg gave the Union army a victory that turned back the boldest and

perhaps greatest chance for a Southern nation. Continued below...

Now, acclaimed

historian Noah Andre Trudeau brings the most up-to-date research available to a brilliant, sweeping, and comprehensive history

of the battle of Gettysburg that sheds fresh light on virtually every aspect of it. Deftly balancing his own

narrative style with revealing firsthand accounts, Trudeau brings this engrossing human tale to life as never before.

Recommended Reading:

General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse. Review:

You cannot say that University of North

Carolina professor Glatthaar (Partners in Command) did not do his homework in this massive examination

of the Civil War–era lives of the men in Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia.

Glatthaar spent nearly 20 years examining and ordering primary source material to ferret out why Lee's men fought, how they

lived during the war, how they came close to winning, and why they lost. Glatthaar marshals convincing evidence to challenge

the often-expressed notion that the war in the South was a rich man's war and a poor man's fight and that support for slavery

was concentrated among the Southern upper class. Continued below...

Lee's army

included the rich, poor and middle-class, according to the author, who contends that there was broad support for the war in

all economic strata of Confederate society. He also challenges the myth that because Union forces outnumbered and materially

outmatched the Confederates, the rebel cause was lost, and articulates Lee and his army's acumen and achievements in the face

of this overwhelming opposition. This well-written work provides much food for thought for all Civil War buffs.

|