|

"We

were left in a critical position."

Charles W. Reed, 9th Massachusetts Battery

Excerpt from "WE SAVED THE LINE FROM BEING BROKEN" by Eric A. Campbell

Gettysburg

National Military Park, March 23, 1996

| Captain John Bigelow |

|

| (USMHI) |

"He is worse than any regular that ever breathed" was how

Charles Reed described Captain John C. Bigelow, the new commander of the 9th Massachusetts Battery. The arrival of Captain

Bigelow in late February 1863 changed the lax and some what care-free lives for the men in the 9th Massachusetts Battery and

within days the batterymen thought the captain to be a tyrant, including Reed: "He dont have...the feelings for his men as

a slave owner for his slaves. He has been order[ing] eight roll call’s a day. in fact they are regular dress parades

which precede all the drill call’s[,] stable, and water calls." Little did Reed realize at that time, that Bigelow's

discipline and unceasing drill would save the lives of most of his fellow batterymen at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Charles Wellington Reed was born in Charlestown, Massachusetts on April

1, 1841, the third child of Joseph and Roxanna Reed. The family’s ancestry was rich. His great-grandfather (Swithin

Reed) immigrated to American in 1740, his grandfather (Isaac Richardson) had been wounded at the Battle of Lexington during

the Revolution and his father had served during the Mexican War. Despite this lineage, his immediate family’s financial

and social status was only moderately acceptable. Of average height and slight in built, Reed was articulate, industrious,

eager and showed a talent for drawing, art and music. After graduating from public schools in Charlestown and Boston, Reed

was working independently as a illustrator and lithographer when the war began. Uncertain of his future career path and seeking

an opportunity to advance his talents, Reed enlisted as a bugler in the 9th Massachusetts Battery on August 2, 1862 for three

years or the end of the war.

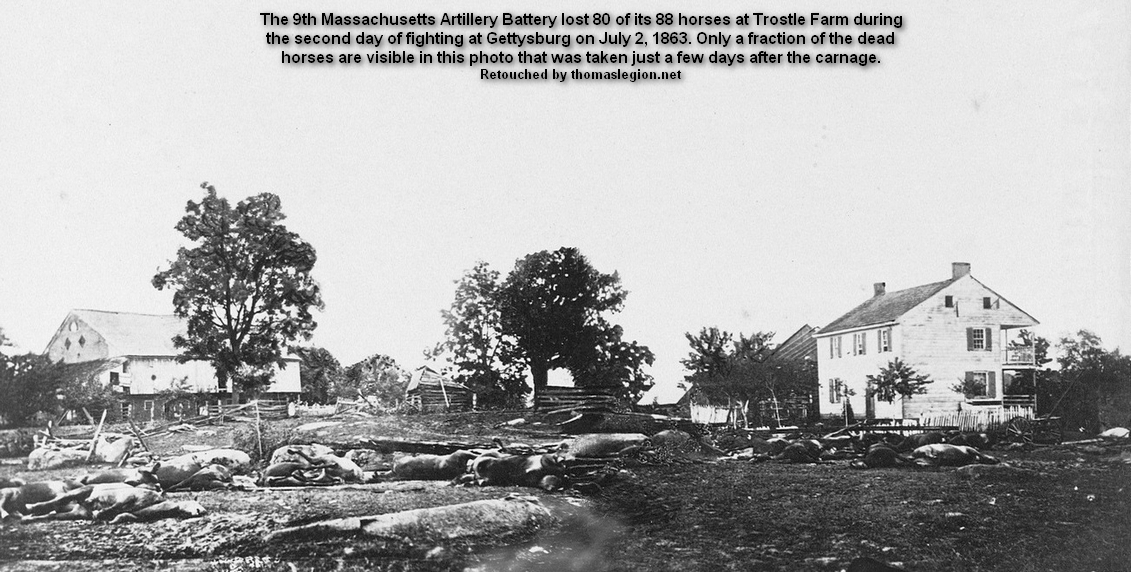

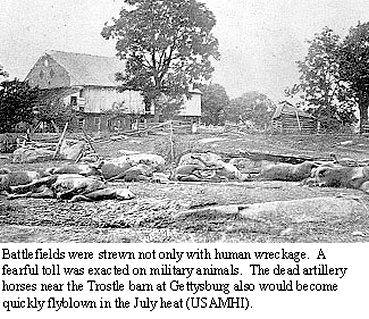

| Trostle Farm, Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

|

| Dead horses at Trostle Farm during Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863 |

(About) The 9th Massachusetts Battery suffered 80 dead horses during the fight at Trostle,

July 2nd, 1863, at Gettysburg. The Battle of Gettysburg, like the majority of Civil War battles, raged over the private

property of ordinary farmers and citizens. The buildings on these properties, if they were not destroyed, were often

converted into field hospitals to treat wounded and dying soldiers. On the Trostle homestead, July 2, 1863, as waves

of gray-clad men continued to press its front, the 9th Massachusetts, now engaged in a very deadly contest,

was ordered to fire double-canister at the advancing Confederates. As canister cracked and peppered the field, the

gray wave, not faltering, had pushed through the dense smoke and closed the already shortened field between

the foe. Too late to limber and move the artillery, understood the Union men, who were now facing superior numbers without

their equalizers of canister and shot. On the Confederate side, the sounds of cold steel rattling and clanking could

be heard as some of the men had transitioned to fixed bayonets. "Shoot the horses!" shouted one soldier of the 21st

Mississippi Infantry, and the animals fell in heaps still strapped to their harnesses. Passing enemy cannon muzzles

the Rebels were met with determined artillerymen who fought back with hand spikes, rammers, pistols, and fists. "We fought

with our guns until the rebs put their hands on (them)," wrote Private David Brett. "The bullets flew thick as hailstones...

It is a mericle(sic) that we were not all killed." The survivors finally fled, leaving behind guns, limbers, and the wounded

and dead intermingled with the dead and dying horses. The first battle experience of the 9th Massachusetts Battery had ended

in a bloody disaster. The battery suffered 80 of its 88 horses in killed, and the fallen equines covered every portion

of the Trostle yard.

| Charles W. Reed |

|

| (Library of Congress) |

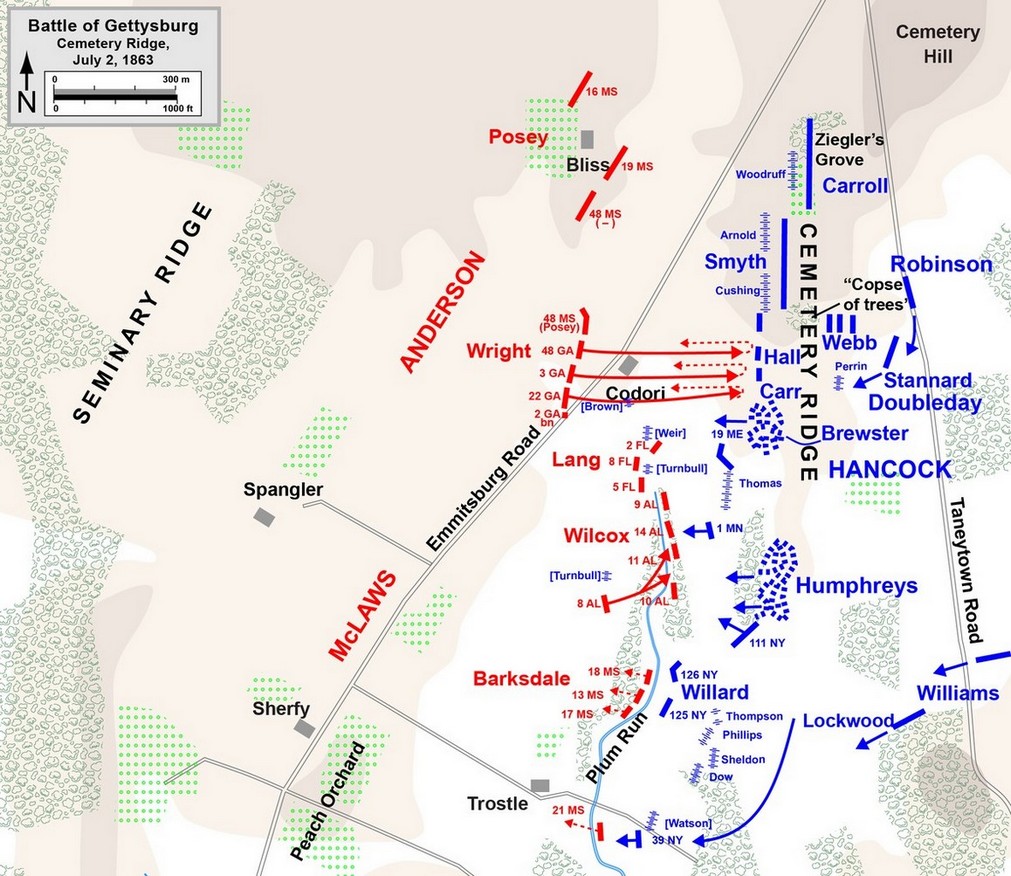

| Second Day at Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| The Fight at Trostle Farm, July 2, 1863 |

To the twenty year old Reed, the war seemed a great adventure and a chance

to travel, visit sites he had only read about and be a witness to what he realized was a great event in history. Not only

did he witness it, but Reed recorded much of what he saw. Most of his letters were embellished with drawings and he filled

several sketch books throughout the war. The adventure seemed to be restricted with the arrival of Captain Bigelow who instilled

discipline through strictness to regulation, repeated drilling and insistence on the unquestioning obedience of orders. The

battery consisted of 104 officers and men, 110 horses and six bronze 12-pounder smoothbore cannon, nicknamed the "Napoleon".

Not surprisingly, the unit's morale, discipline and confidence grew steadily each day. Begrudgingly, Reed later wrote that

Bigelow "understands his business. Lately he has relaxed his strictness...I think his strictness was to make the men know

what he is made of." The discipline instilled in the young artillerymen would soon be necessary, for their first experience

in combat was to take place that summer at a Pennsylvania cross-roads town called Gettysburg.

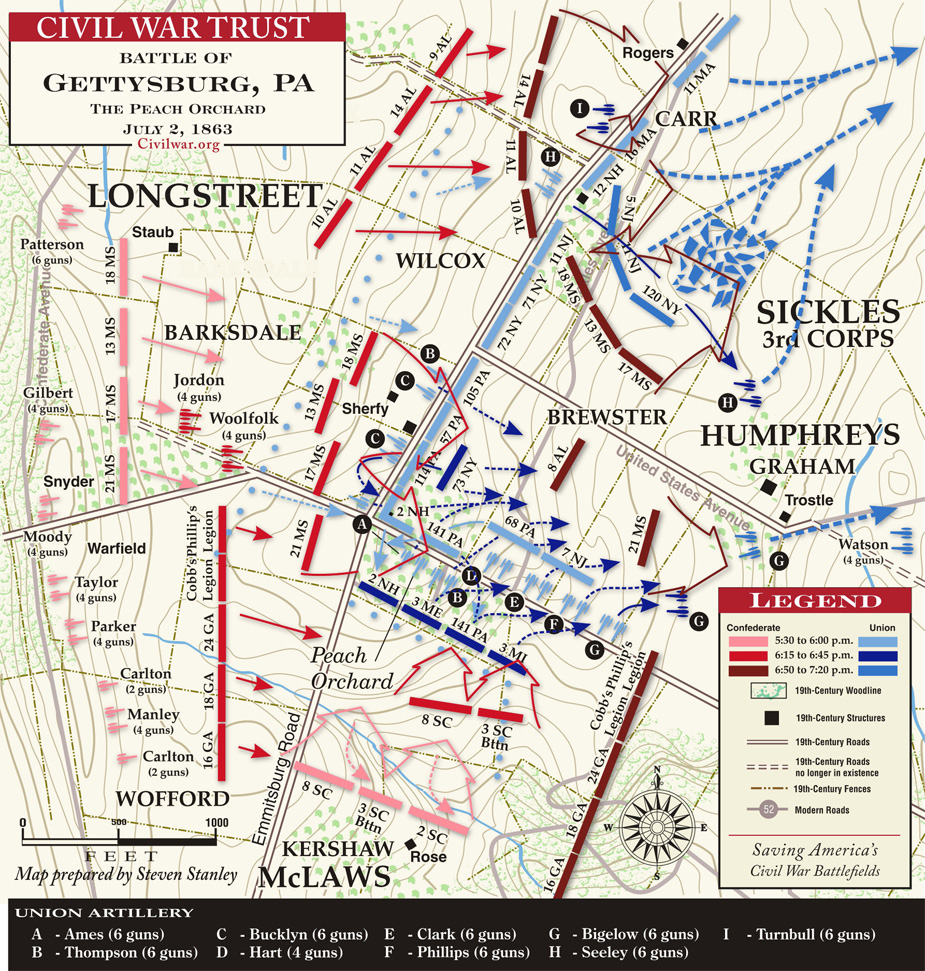

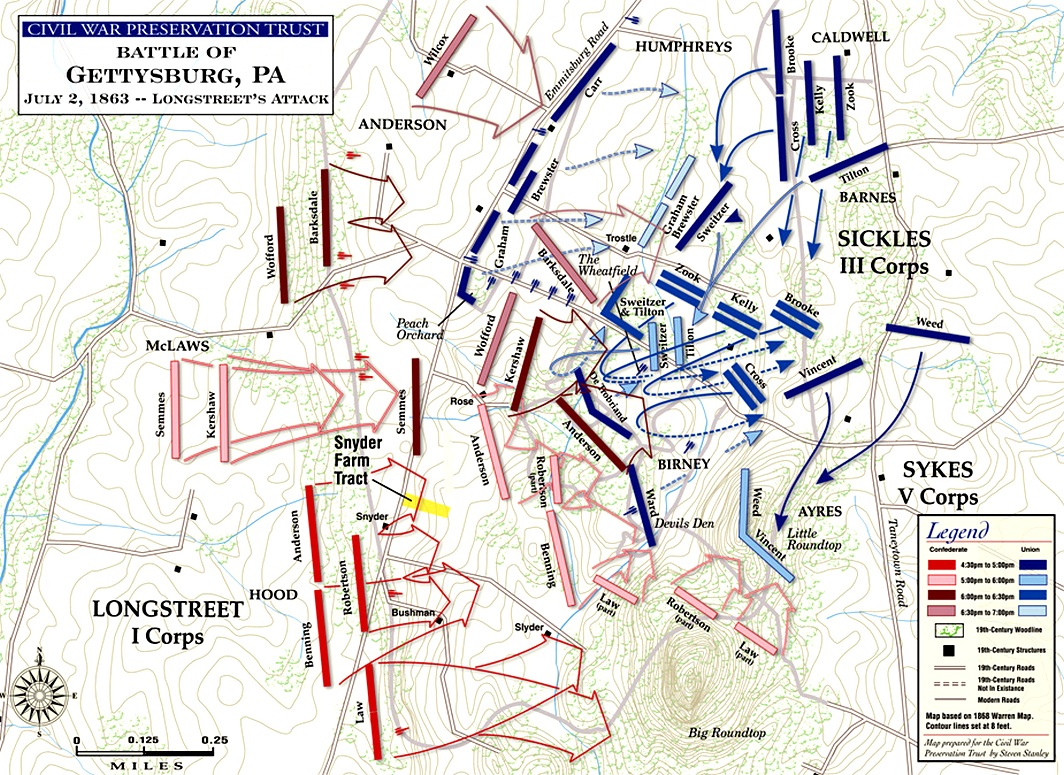

On June 25, 1863 the 9th Massachusetts Battery, found itself marching in the ranks of the Army of the Potomac. Reed and his comrades soon discovered they had been assigned to the 1st Volunteer Brigade commanded by Lt. Colonel Freeman

McGilvery. The brigade was part of the Artillery Reserve which arrived on the battlefield about mid-morning of July 2, and

was placed behind the lines and held in readiness to be used when and where it was needed. The principal Confederate attack

began that afternoon when Southern troops of Lt. General James Longstreet's Corps struck the Union left. Defending this area

was the Third Corps, Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. General Daniel Sickles. Earlier that afternoon this flamboyant

commander, in one of the most controversial decisions of the battle, had pushed his corps forward to an advanced and overextended

position. His troops under heavy attack, Sickles sought reinforcements to bolster his thin line. A rapid series of orders,

arriving within a matter of minutes, had McGilvery leading all four of his batteries to the support of Sickles and his Third

Corps.

|

| (Library of Congress) |

(Left) General Sickles & staff at his headquarters, sketched by Charles

Reed on July 2. Picture Library of Congress.

Bugler Reed sounded "Assembly", and "drivers mounted and within five minutes

we were off at a lively trot, following our leader to the left, where the firing was getting to be the heaviest." Though almost

all of the 1st Volunteer Brigade, including Bigelow and McGilvery were combat veterans, the men of the 9th Massachusetts Battery

were moving into their first battle. Naturally many of the gunners were nervous. Yet others, probably eager and naive, were

like Reed: "I must say I was surprised at myself in not experiencing more fear than I did as it was it seemed more like going

to some game or a review...." The batteries trotted cross-country, skirting fields and woods toward the fighting, and finally

arriving at Gen. Sickles’ headquarters near the Abraham Trostle farmstead [Battle of Gettysburg : The Trostle Farm and Plum Run]. The batteries "doubled up" and the men began to wait as McGilvery conferred with Sickles. Captain Bigelow described the

scene: "A spirited military spectacle lay before us; General Sickles was standing beneath a tree close by, staff officers

and orderlies coming and going in all directions; at the famous 'Peach Orchard' angle on rising ground along the Emmetsburg

Road, about 500 yards in our front, white smoke was curling up from... the deep-toned booming of [Union] guns...while the

enemy’s shells were flying over or breaking around us."

Nervously the drivers and gunners waited by their guns for orders, watching

the spectacle of their first battle along the Third Corps front. Reed, possibly more excited than others by the momentous

event unfolding before him and realizing its importance, decided to record the scene. Incredibly he pulled out his sketch

pad and began to draw. He later wrote: "at the foot of the hill...were Maj. Gen. Sickles headquarters under a tree. We halted...a

few minutes giving me time to take a scetch of him. One of his Aids was already wounded by a piece of shell in the back and

the surgeon was doing it up." Within a few moments, Captain Bigelow returned to the battery, lieutenants shouted out orders,

drivers spurred their teams, and the battery raced to their assigned positions.

| Trostle Farm and Plum Run, Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Trostle Farm and Plum Run, Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

(Left) Charge of the 9th Massachusetts Battery to its first position on

the Wheatfield Road. Photo courtesy Charles Reed, History of the 9th Massachusetts Battery.

Taking advantage of elevated firing positions east of the Peach Orchard, McGilvery placed all four batteries along the Wheatfield Road, facing southward

so they "commanded most of the open country" to their front. They were, from right to left, Capt. James Thompson’s Battery

C & F, 1st Pennsylvania, Capt. Patrick Hart’s 15th New York, Capt. Charles Phillips’ 5th Massachusetts and

Bigelow’s 9th Massachusetts. The batteries covered a dangerous 400 yard gap in the Union line between the Peach Orchard

and Wheatfield that existed because Sickles had overextended his line in taking up his advanced position. The guns went into

line alone, without infantry support which made them vulnerable. Despite this, gunners raced into position while under fire

and quickly readied for action to duel with Confederate artillery nearly a mile away. Reed observed, "There were five Batterys

of us in a line...besides other artillery in different positions[,] the roar of which was deafening."

The 9th Massachusetts was swept by Confederate artillery fire.

"Our position was open and exposed," Captain Bigelow reported. "One man was killed and several wounded before we could fire

a single gun.... (We) soon covered ourselves in a cloud of powder smoke, for our six Light Twelve guns were rapidly served."

The tremendous noise was overwhelming as Reed wrote, "such a shrieking, hissing, seathing I never dreamed was imagineable,

it seemed as though it must be the work of the very devil himself."

(Left) The 9th Massachusetts

Battery with other Union batteries on the Wheatfield Road. The Peach Orchard is in the center background. Charles Reed, Regiments

and Armories of Massachusetts.

Shortly after taking up its position, "on that memoriable day and our battery

fairly at [it]," Reed continued, "(the) Captain ordered me to the rear[,] saying there was no need of my being there." Bigelow

must have felt there was no use for a bugler with the deafening noise. Reed obeyed "and rode back two or three rods" but then

changed his mind, as he related to his sister: "...somehow I coud’nt see it. I was bound to see a fight and might be

of some use after all so I disobeyed orders by turning round [and] going up to the battery again..." It turned out to be a

good decision as Colonel McGilvery was short on staff officers: "I was right [to return] for presently Major McGilvray(sic)...came

up and set me at it in the shape of transmitting orders from one bat’ry to another, which suited me to a T as I had

a wider field under my eyes and could see what was going on farther to our right and left[.] some new Batterys opened on us

a cross fire with shell and solid shot[.] their fire about this time was tremendous."

McGilvery reported this enfilading fire, but his men were powerless to counter

it. Because the Third Corps line angled back at the Peach Orchard, Sickles’ front essentially faced two directions-

west and south. The converging fire of Confederate batteries from those directions enfiladed both wings of the Third Corps

line. The artillerymen in McGilvery’s command suffered under this convergence of fire, but stuck to their guns. Then

at "about 5 o’clock a heavy column of rebel infantry made its appearance in a grain-field about 850 yards in front,

moving at double quick time toward the woods on our left, where the infantry fighting was then going on." A half-hour later,

"the battle...raged along the lines...(as) another and larger column appeared...."- the combined assault of Brig. General Joseph B. Kershaw's and Brig. General Paul Semmes’ brigades, advancing from Seminary Ridge toward the Wheatfield. At a distance of less than 400 yards, these Confederates marched directly across

the front of McGilvery, "immediately trained the entire line of our guns upon them, and opened with various kinds of ammunition."

(Left). "Lieut. Erickson... reeling in the saddle, he was frothing (blood)

at the mouth" Disregarding a gunshot wound to his chest, Lt. Christopher Erickson remained at his post directing his section

of the battery. The young officer was killed moments later. Charles Reed, Library of Congress.

As the range decreased the batteries switched to canister, shotgun-like

blasts that tore "great gaps" through the Confederate ranks. A South Carolinian of Kershaw's Brigade recalled, "O the awful

deathly surging sounds of those little black balls as they flew by us, through us, between our legs, and over us! Many, of

course, were struck down...."

The batteries were still under Confederate artillery fire and Reed experienced

a narrow miss. "I had just been along the line of batterys that were [in] line...with an order from the Col to double shott

the guns with canister and returning a shell tore up the ground in front of my horse at which he halted so suddenly...as to

almost throw me out of the saddle."

Continuing on his mission, Reed glanced at the scene before the guns: "down

came the Rebs...from the right behind a white fence when opposite us they left flanked and steadily advanced on us...." The

South Carolinians closed to within two hundred yards, when suddenly their direction of advance shifted to their right, thus

moving parallel to the artillery. The artillerymen quickly took advantage, as Captain Bigelow reported: "...the Battery immediately

enfiladed them with a rapid fire of canister, which tore through their ranks and sprinkled the field with their dead and wound,

until they disappeared in the woods on our left, apparently a mob."

Though the initial Confederate assault had been repulsed, the situation remained

critical for all of McGilvery’s batteries. Kershaw’s men quickly rallied and were "not long in taking...revenge."

Closely watching the shifting Confederates, Bigelow found that "as soon as the woods were reached, [they] sent a body of sharpshooters

against us." Reed later wrote that the men "advanced on us giving us such a shower of small balls that it was dangerous to

be safe!" In their position on the far left, the 9th Massachusetts Battery received the brunt of the Confederate fire from

the front and left. The Confederates "came up on my left front as skirmishers, pouring in a heavy fire and killing and wounding

a number of...my men," Captain Bigelow recalled. At his battery post, Private David Brett was horrified: "We could hear the

bullets pass us[.] finily a man dropt about 6 foot to my right another right behind[.] 6 men were killed within a rod of me...."

| Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| 9th Massachusetts engages at Trostle Farm, July 2, 1862 |

(Left) Chaos at the Trostle Farm. A caisson team attempts to dash over the

stone fence as the remaining guns are overrun. USMHI, Carlisle.

Fighting raged in the Wheatfield east of the 9th Massachusetts Battery and

along the front. Conditions continued to deteriorate until, shortly after 6:00 P.M. when the situation reached a critical

point. At that time, the growing Confederate assaults reached the salient angle of Sickles’ line at the Peach Orchard.

Under the relentless advance of the brigades of Brig. General William Barksdale and Brig. General William T. Wofford, the

Union line began to crumble. Though making a determined stand, the Union infantry slowly melted away from the "compact mass

of humanity" of Barksdale’s regiments. This stand allowed Union artillery in the orchard time to escape, though the

right door was now open to take McGilvery’s line under fire.

McGilvery ordered two of his batteries to retreat while his last two, Phillips

and Bigelow, continued to thunder away at Kershaw’s men. Barksdale’s regiments advanced through the orchard after

smashing the Union line located there, and prepared to rush down the slope into the unsuspecting artillerymen. McGilvery next

rode to Phillips and ordered him to retreat, intending to have his remaining batteries, "retire 250 yards and renew their

fire," probably hoping to reform the broken line, or somehow stem the flow of retreating Union troops. But the situation was

unraveling too rapidly. By the time McGilvery reached the 9th Massachusetts Battery he was ordering his batteries back to

Cemetery Ridge. Bigelow’s men had been steadily working their guns in a futile attempt to hold back the increasing Confederate

pressure from the left and front. In the noise and confusion of battle, Charles Reed took no notice of the other batteries

withdrawal as "we were so intent upon our work that we noticed not when the other batterys left." It was Captain Bigelow who

spotted the new threat coming from the direction of the orchard: "Glancing toward the Peach Orchard on my right, I saw that

the Confederates (Barksdale’s Brigade) had come through and were forming a line 200 yards distant, extending back, parallel

with the Emmitsburg Road, as far as I could see... Colonel McGilvery rode up, at this time, and told me that (all of Sickles’)

men had withdrawn and I was alone on the field, with no supports... limber up and get out."

(Left) The Trostle

Farm House, July 5-6, 1863. Wreckage of the 9th Massachusetts Battery remains scattered around the farm buildings. National

Archives.

Bigelow realized the order could not be carried out, for without infantry

support and with Confederate skirmishers so close, "every saddle would have been emptied in trying to limber up." Making a

swift decision, the captain petitioned McGilvery to "‘retire by prolonge and firing,’ in order to ‘keep

them off.’" This bold decision obviously revealed the confidence Bigelow placed in his men, for to attempt such a maneuver

was extremely risky, especially with untried troops. Many obstacles and problems could develop which could result in disaster

for the battery. McGilvery also must have realized the risk, but quickly "assented [to the request] and rode away." Whatever

the reason, orders were quickly given, prolonge ropes fixed and the battery began to withdraw. "No friendly supports, of any

kind, were in sight; but Johnnie Rebs in great numbers," Bigelow recalled. "Bullets were coming into our midst from many directions

and a Confederate battery added to our difficulties. (The) Battery kept well aligned in retiring, (moving) with a slow, sullen

fire." Drivers coached their straining horse teams as they dragged the heavy guns through the pasture south of the Trostle

buildings. Gunners rammed charges down the hot muzzles as they moved, stopping briefly to fire the weapons, "keeping Kershaw’s

skirmishers back with canister, and the other two sections bowling solid shot towards Barksdale’s men."

Lt. Colonel McGilvery galloped to the rear in order to regroup and reorganize

his withdrawing batteries along Cemetery Ridge. Reaching the higher ground beyond, however, McGilvery was shocked to find a

huge gap in the center of the Union line. In his mind, "The crisis of the engagement had now arrived," and he knew that Bigelow's

gunners would have to buy time for his other cannoneers. Spotting the 9th Massachusetts Battery, which had just halted under

cover of a slight knoll near the Trostle farmstead and was beginning to limber up in preparation for retreat, McGilvery spurred

his horse, "alone, in the midst of flying missiles" toward the battery. His horse staggered, being "shot four times in the

breast and fore shoulder," as he reined up in front of Captain Bigelow. "Captain Bigelow, there is not an infantryman back

of you along the whole line which Sickles’ moved out; you must remain where you are and hold your position at all hazards,

if need be, until at least I can find some batteries to put in position and cover you!"

McGilvery and Bigelow both knew the consequences of these orders. Bigelow

realized, "the sacrifice of the command was asked in order to save the line," and could only manage a weak reply that he would

try.

The men of the battery were equally stunned and Reed knew, "we were left in

a critical position[.]" Bigelow found himself in a, "position...which...was an impossible one for artillery. The task seemed

superhuman, for the knoll already spoken of allowed the enemy to approach as it were under cover within 50 yards of my front,

while I was very much cramped for room and my ammunition was greatly reduced." The exhausted battery was trapped in the angle

of two stone walls, making retreat impossible. Yet the men of the 9th Massachusetts Battery did not hesitate as Bigelow ordered

his men to prepare for action. Most of the soldiers in the battery were just like Charles Reed who, though from common origins

were, according to Bigelow, "Without exception... soldiers only from the highest sense of duty" and fought for a cause in

which they firmly believed. Though earlier given a chance to safely leave the fight, Reed just "could’nt see it," and

had "disobeyed orders" by returning to his battery. One of the battery's corporals best summed up the feelings of all the

men in the battery when he later proudly wrote, "We the Glorious-young 9th Mass- Battery in Splendid Organisation and for

the first time in an engagement - stood the ground and were Willing to die for the Contry."

| Second Day, Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Longstreet's Assault at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863 |

| Main Artillery at Gettysburg |

|

| (Gettysburg NMP) |

Realizing desperate circumstances required desperate actions, Bigelow took

chances. Risking the danger to his own men, the captain ordered all the ammunition laid beside the guns for "rapid firing."

Utilizing every means possible to slow the advancing Confederates, he then ordered his four guns in the center and right,

to "commence...firing solid shot low, for a ricochet over the knoll" and into the infantry beyond. With his six pieces loaded

and arranged in a semi-circle, with the limbers and horses crowded into the corner of the stone walls, the battery soon fell

silent to await the onslaught. "The moments seemed like hours," Bigelow recalled, the guns prepared "not a moment too soon...for

almost immediately the enemy appeared over the knoll. Waiting till they were breast high, my battery was discharged at them(,)

every gun loaded...with double shotted cannister and solid shot, after which through the smoke [we] caught a glimpse of the

enemy, they were torn and broken, but still advancing. The enemy opened a fearful musketry fire, men and horses were falling

like hail.... Sergeant after Sergt., was struck down, horses were plunging and laying about all around...."

These tenacious troops were approximately 400 men of the 21st Mississippi

Infantry, which struck the right and front of the battery. At the same time skirmishers from Kershaw’s Brigade, who

had doggedly followed Bigelow’s guns, threatened from the left front. Flushed with victory, the Mississippians pushed

onward, "yelling like demons," as "Again and again they rallied." Directing the battle from his horse, Bigelow witnessed,

"The enemy crowded to the very muzzles [of the guns] but were blown away by the canister. Notwithstanding their insane, reckless

efforts not an enemy came into [the] battery from its front. (The) rapid fire recoiled the guns into the corner of the stone-wall,

(which) more and more cramped my position." Canister ammunition began to run low as Bigelow, still willing to take risks,

ordered case shot with the fuzes cut short to be used, "so that they would explode near the muzzle of [the] guns. (Yet the

Confederate) lines extended far beyond our right flank, and the 21st Miss.,...swung without opposition and came in from that

direction, pouring in a heavy fire all the while."

(Left) Reed saves Captain Bigelow. Photo by Charles Reed, Regiments

and Armories of Massachusetts.

Caught in a "withering cross fire," and with his left section entangled among

some large bowlders" and the stone wall, Bigelow ordered those guns to retire. After quickly limbering up the crews headed

for their only escape, an opening in the stone wall opposite the Trostle farmyard. The first gun, however, upon reaching the

gateway, overturned and blocked it. While the men of this gun scrambled to right it, the crew of the trailing gun looked in

desperation for a way out. A few men "tumbled the top stones off the wall" before the drivers headed "directly over the wall."

Aghast at the spectacle, Reed remembered the "horses jumping and the gun...going over with a tilt on one side and then a crash

of rocks and wheels" as the piece made its successfully flight.

Desperately Bigelow gave orders for the remaining crews to prepare for a general

retreat and "rode to the stone wall, hoping to stop some of [the] cannoneers and have them make a better opening, through

which I might rush one or more of the remaining four guns...." But with the left section gone, Kershaw’s skirmishers

"being unchecked, quickly came up on [the] left and poured in a murderous fire." At his captain’s side, Bugler Reed,

recalled "I saw the enemy skirting down the stone wall...and called to the captain to look out," while at the same time "throwing

his horse back on his haunches." Bigelow never heard the warning as six skirmishers opened fire and the captain "caught two

bullets, my horse two, (and) two flew wide."

As his horse staggered to the rear, the dazed captain fell near the wall.

Reed and Bigelow’s orderly were quickly by their commander’s side. As he leaned against the wall, Bigelow saw

"the Confederates swarming in on our right flank." Hand to hand fighting engulfed the battery, the men using handspikes and

rammers to defend their guns. With all the remaining officers and most of the sergeants also killed or wounded, the air...alive

with missiles, and the battery caught in a turmoil of confusion, the resistance of most units would collapse. The men of the

9th Massachusetts Battery did not flinch; instead they stood to their guns, their discipline holding them together. "We fought

with our guns untill the rebs could put heir hands on [them]," wrote Private David Brett. "The bullets flew thick as hailstones...it

is a mericle that we were not all killed...not a man run[,] 4 or 5 fell within 15 feet of me."

Bigelow witnessed the melee, Confederates "standing on the limber chests,

and shooting down cannoneers. Not even then did the batterymen cease their fire. Longer delay was impossible, (and) having

thus accomplished what was required of my command," he gave the order to retreat. The men abandoned the death trap and made

their way to the rear, leaving behind the shattered remains of the battery and a sacrifice of three of four officers, six

of eight sergeants, 19 enlisted men, 88 horses and four of their six guns." In the midst of this chaos, Reed remembered his

wounded captain "told...the orderly and myself to leave him and get out as best we could. (I) didn't do just that." Reed again

disobeyed orders. Years afterward, Bigelow could not forget the actions of his faithful bugler: "He remained with me...called

my orderly and had him lift me on to his horse; then taking the reins of both horses in his left hand, with his right hand

supporting me in the saddle, took me at a walk [to the rear]." See also Life of a Civil War Horse and Civil War Horses of the Union and Confederate Armies.

|

| 9th Mass. Battery Monument at Trostle Farm |

(Right) The 9th Massachusetts Battery Monument at the Trostle Farm, dedicated

by veterans of the battery in 1885, where the battery made its final stand on July 2nd, 1863. Gettysburg NMP.

| Dead horses of Gettysburg |

|

| Horses killed at Trostle during Battle of Gettysburg |

"Then we tried to get away," Reed wrote. "Some of the confederates saw us...and

several of them tried to take us prisoners. They did not fire at once, but tried to pull us from the horses’ backs,

but were unsuccessful, as the horses kicked and I was able to do some execution with my...saber.... We were still struggling

when an officer, who saw his men were about to fire, told them not to murder us in cold blood. Then I started for the northern

forces." The wounded captain and his bugler were now between the battle lines, "the shells of the Enemy...breaking all around

us." They had over 400 yards of open ground to cross before reaching safety. "Before I was half way back," Bigelow remembered

an officer was sent "urging me to hurry, as he must commence firing." The captain’s painful wounds, however, prevented

the horses from moving at anything faster than a walk, so Bigelow told him to "fire away." Now caught between the fire of

both lines, Reed also had to contend with the orderly’s frightened horse, which was difficult to control. Bigelow later

praised Reed's conduct: "Bugler Reed did not flinch; but steadily supported me; kept the horses at a walk although between

the two fires and guided them, so that we entered the Battery between two of the guns that were firing heavily....

Less than four months earlier, Reed had labeled his commander "a regular arristocrat,"

feeling he was worse than a slave owner. Yet in the heat of battle, the bugler twice disobeyed orders and willingly risked

his life to save his captain. Bigelow never forgot Reed’s "gallantry," writing to him thirty-two years, "the obligation

still remains with myself." Bigelow felt so strongly about this that in 1895 he submitted Reed’s name for a Medal of

Honor, citing his "distinguished bravery and faithfulness to duty at the Battle of Gettysburg." When the medal was awarded

later that year Bigelow stated "I feel the Government honors itself in honoring you." On a more personal level, Bigelow felt

Reed had not only saved him from a stint in a Confederate prison but, more importantly, had also saved his life. The captain

later wrote, "Even though the Mississippians would probably have spared me, Dow's (6th Maine) searching canister and Shells

would not have done so."

The 6th Maine Battery, commanded by Lt. Edwin B. Dow, was one of six full

or partial batteries that formed McGilvery’s new artillery line on Cemetery Ridge. The 21st Mississippi Infantry, soon

after capturing Bigelow’s guns, regrouped and charged McGilvery’s new line, making Watson’s Battery I, 5th

U.S. Artillery their target. The regulars fired twenty rounds of canister into the approaching Mississippians, before coming

under a killing musketry fire. Watson was wounded and so many of his "men and horses were shot down or disabled...that the

battery was abandoned." East of the overrun battery, McGilvery's new line blasted the Confederates before they could go further.

Gathering along the banks of the slow moving Plum Run, Barksdale's soldiers attempted to get reorganized. Suddenly they were

struck by a vicious Union counterattack which eventually drove the Mississippians back, leaving their mortally wounded general

in Union hands.

Lt. Colonel McGilvery's swift action and the determination of the 9th Massachusetts

Battery had helped close the critical gap in the Union line, a point not lost on the battle's participants. Charles Reed,

in a letter written just seven days later, wrote, "we saved the line from being broken."

The artillery branch of the Army of the Potomac had indeed made a tremendous

contribution to the Union cause on July 2, 1863. Union batteries, despite the extremely adverse conditions in which they were

positioned, including lack of proper support, and under tremendous pressure, had assisted in turning back numerous Confederate

assaults. Many factors contributed to this success. One of the most important was the officers, such as Freeman McGilvery

and John Bigelow. By using their guns for maximum effect, including the willingness to sacrifice units if necessary, along

with the cool-headed leadership they exhibited, enabled them to hold the batteries together during this crisis. Another factor

was the enlisted men themselves. Soldiers like Charles Reed, whose courage and discipline allowed them to perform beyond expectations.

Though the direct association of these three men lasted less than six months,

they had made a difference at Gettysburg. The fortunes of war, however, held a different fate for each.

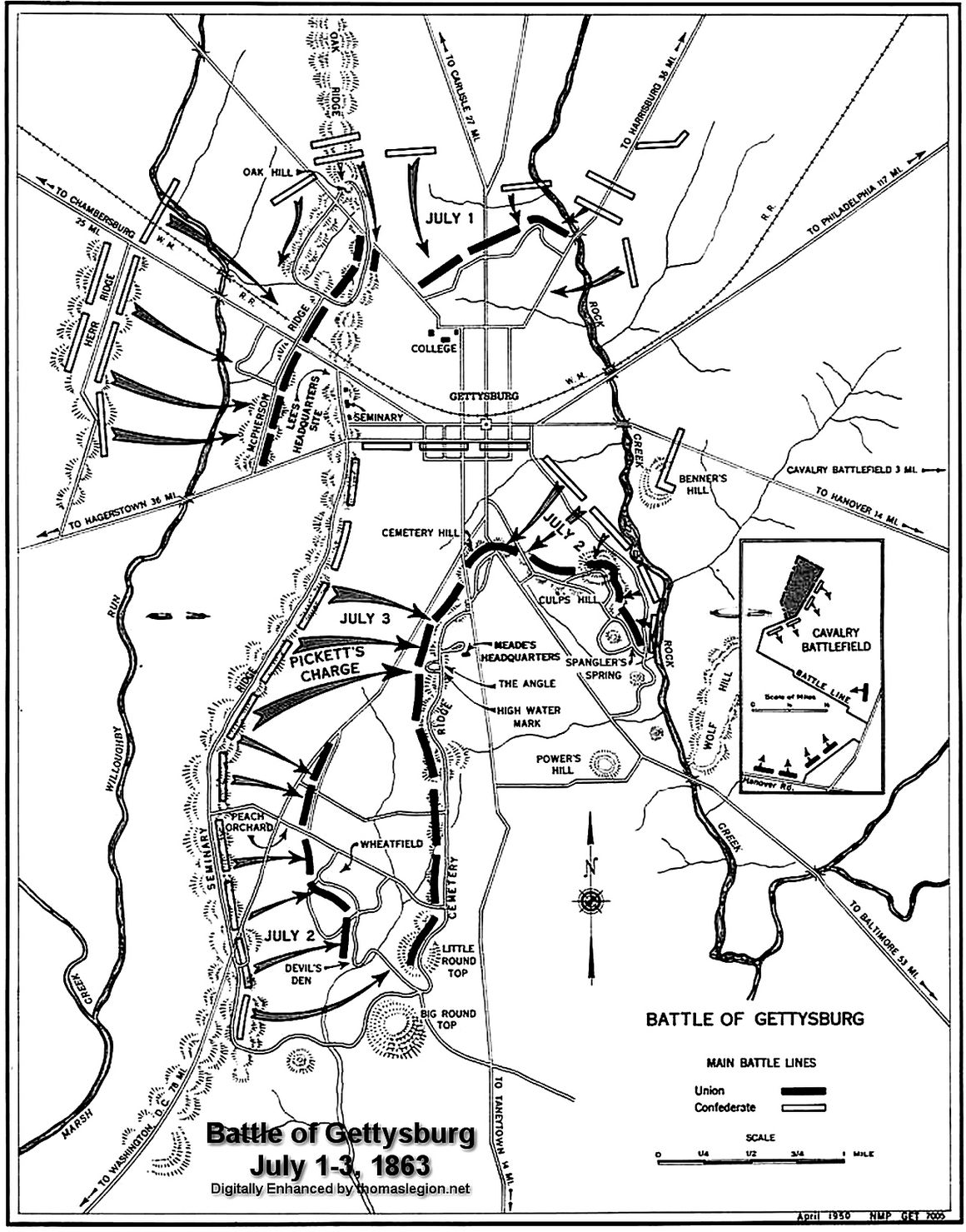

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863 |

|

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863 |

Captain John Bigelow recovered from his Gettysburg

wounds and returned to the 9th Massachusetts Battery later that summer. He led it through

numerous actions during the fall campaign of 1863, the Overland Campaign of 1864 and during the Siege of Petersburg, eventually being brevetted to major for gallantry. He fell ill in the

fall of 1864, however, and was discharged for disability on December 31. His farewell order to the battery, summed up his

attitude on what made them "veterans, who have won an enviable name," reminding them their reputation was earned through

"strict discipline and ready obedience." Bigelow benefited from his military service in a post-war career that, though far

less glamorous, was highly productive. In Boston he was elected to the State Legislature and later worked as an inventor in

New York City, Philadelphia and finally Minneapolis. The former artillery officer also authored two books before his death

in 1917. Not surprisingly, The Peach Orchard (1910) and Supplement to Peach Orchard (1911), both dealt with

the role of artillery at Gettysburg. These writings not only reveal the hold the battle had on the former officer, but also

the lack of recognition his arm of service had received in the post war years. Bigelow’s writings were also an attempt

to give his former commander the proper credit he rightfully deserved:

"Col. Freeman McGilvery of Maine, Commander First Volunteer Brigade,

Artillery Reserve, Army of the Potomac, was one of the real heroes of the battle of Gettysburg.... McGilvery, with his Artillery

alone, stayed the advancing enemy and prevented their discovery of the opportunity offered for success. This feat of arms,

requiring the sacrifice of many lives and the wounding of many men, we believe should be recognized and honored.... His Comrades

and his State may well demand, that his services...receive some proper recognition."

Indeed, Lt. Colonel Freeman McGilvery’s status seemed to be

on the rise after Gettysburg. He continued to command a brigade in the Artillery Reserve until May, 1864, and then took command

of the army’s artillery park and train, which he lead through the Overland Campaign and during the early stages of the

Petersburg siege. On August 9, 1864 he was promoted to Chief of Artillery, 10th Army Corps, commanding fifteen batteries.

A cruel fate, however, would tragically cut short McGilvery’s promising military career. On August 16, while overseeing

his batteries during the engagement at Deep Bottom, he was slightly wounded in the left forefinger. Being faithful to see

his duties though, he remained at his position throughout August, during which "his labors were unremitting." Not surprisingly,

the wound did not heal properly and he consented to surgery. During a seemingly simple operation on September 3, 1864, McGilvery

"died suddenly... from the effects of chloroform taken during amputation of [his] finger." Freeman McGilvery's untimely death

sadly diminished the chance for proper recognition of his services, not only at Gettysburg, but on countless other battlefields.

Charles Reed served with the 9th Massachusetts Battery

until November, 1864, when he was detailed to the topographical engineers, the army at long last taking advantage of his artistic

ability. The war allowed Reed to improve his talent, for he established himself as a well-known artist upon his return to

Boston. His illustrations appeared in the Boston Globe, and in numerous books, such as Hard Tack and Coffee

and Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Reed's drive enabled him to continue working well into his early 80's until

his death on April 24, 1926. Throughout his life, the former bugler managed to stay in touch with his former commander, and

then friend, John Bigelow. Like other veterans of the battery, Reed was fond of his former captain, recalling, "we are proud

of all of our officers[,] they were constantly in the thickest of the fighting[.]"

To all the men who served in the Union artillery at Gettysburg, it seems their

fate was to be "unsung heroes." Despite the sacrifice, courage and devotion of soldiers just like McGilvery, Bigelow and Reed,

history has accorded them a secondary role in the battle. In a larger sense, however, what future glory or recognition they

would receive meant nothing to these men during the war. What they had lost was foremost in their minds; not only their comrades,

but also their innocence. The war had changed them forever as Charles Reed related in a letter home:

|

"During the din of battle my feelings were curious and various but the

one idea I entertained could not be shaken off until the fight had ceased for the day. it appeared to be a grand terrible

dramma we were enacting and the idea of being hit or killed never occured to me, but when I saw the dead, wounded, and mutilated

pouring our their lifes blood...then the terrible sense of reality came upon me in full force. the novelty had vanished. I

could only turn my thoughts to him who sees and controls all, with silent thanks giveings and weep for the many, many dead

and maimed." |

(See also related reading below.)

Sources: National Park Service; Gettysburg National Military Park; Library

of Congress; National Archives; Civil War Trust.

Recommended Reading: The Artillery

of Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: The battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the apex of the Confederacy's final major invasion of the North,

was a devastating defeat that also marked the end of the South's offensive strategy against the North. From this battle until

the end of the war, the Confederate armies largely remained defensive. The Artillery of Gettysburg is a thought-provoking

look at the role of the artillery during the July 1-3, 1863 conflict. Continued below...

During the

Gettysburg

campaign, artillery had already gained the respect in both armies. Used defensively, it could break up attacking formations

and change the outcomes of battle. On the offense, it could soften up enemy positions prior to attack. And even if the results

were not immediately obvious, the psychological effects to strong artillery support could bolster the infantry and discourage

the enemy. Ultimately, infantry and artillery branches became codependent, for the artillery needed infantry support lest

it be decimated by enemy infantry or captured. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had modified its codependent command

system in February 1863. Prior to that, batteries were allocated to brigades, but now they were assigned to each infantry

division, thus decentralizing its command structure and making it more difficult for Gen. Robert E. Lee and his artillery

chief, Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, to control their deployment on the battlefield. The Union Army of the Potomac

had superior artillery capabilities in numerous ways. At Gettysburg,

the Federal artillery had 372 cannons and the Confederates 283. To make matters worse, the Confederate artillery frequently

was hindered by the quality of the fuses, which caused the shells to explode too early, too late, or not at all. When combined

with a command structure that gave Union Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt more direct control--than his Southern counterpart had over

his forces--the Federal army enjoyed a decided advantage in the countryside around Gettysburg. Bradley

M. Gottfried provides insight into how the two armies employed their artillery, how the different kinds of weapons functioned

in battle, and the strategies for using each of them. He shows how artillery affected the “ebb and flow” of battle

for both armies and thus provides a unique way of understanding the strategies of the Federal and Union

commanders.

Recommended Reading: Civil War

Artillery At Gettysburg (Paperback). Description: There were over

600 artillery pieces at Gettysburg. The guns were managed

and operated by over 14,000 men. In three days over 50,000 rounds were fired. What impact did artillery have on this famous

battle? How efficiently were the guns used? What were the strengths and weaknesses on each side? This outstanding book answers

the many artillery questions at Gettysburg. Using accessible

descriptions, this work details the state of the art of this "long arm" as it existed at the time of the battle. It is an

informative overview of field artillery in general while using the battle of Gettysburg

to illustrate artillery technology. For it was Gettysburg

when the artillery branch of both armies had matured to the point where its organization would stay relatively unchanged for

the remainder of the conflict. Prior to Gettysburg, neither

army had the “same mix of guns” nor, more importantly, the same structure of organization as it did at this battle. Continued below...

The effects

were telling. This book is an artillery 'buff's' delight...The work meticulously examines the forming of

the respective artillery arms of the two armies; the organization; artillery technology; guns; equipment and animals constituting

that arm; ammunition; artillery operations; the artillerymen and, finally, actions of the guns on July 2 and 3....The work

is perfect for someone seeking more data than found in most general histories of the battle...Nicely illustrated to supplement

the text, the succinctly written technical details of ballistics, projectile composition and impact of technology for battlefield

lethality will prove similarly useful and exciting for anyone captivated by the guns of Gettysburg. Cole explains the

benefits and liabilities of each piece of artillery....His use of photographs, diagrams, and maps are excellent and integrate

seamlessly into the text....Not only does it explain why events unfolded the way they did , it helps explain how they unfolded.

No other modern book on Civil War artillery of this size is as detailed...as this book is generally...The author's broad approach

to the whole subject of artillery tactics shine when he compares and contrasts several artillery incidents at Gettysburg that

better explain what was going on at the time....This book is essential for all those interested in Civil War artillery, 19th

century artillery, or just the battle of Gettysburg. I found Civil War Artillery at Gettysburg to be an informative and well written account of the 'long-arm' at Gettysburg. The book is very well-illustrated with maps and photos throughout. I thoroughly

enjoyed this book and highly recommend it.

Recommended

Reading:

Cannons: An Introduction to Civil War Artillery. Description: The concise guide to the weapons, ammunition and equipment

of Civil War artillery; includes more than 150 photos and drawings. While this might look like a simple kids book/pamphlet

on the cover, there is far more inside this extremely well illustrated guide. Continued below...

The author does a fine job providing a wide overview of the most important cannons of the American Civil

War, textual summaries of each and sufficient details of their fundamental statistics. The amazing part is how much the author

has fit between a mere 72 pages. This work is very inexpensive and should prove useful to anyone touring Civil War battlefields,

interested in Civil War gaming, reenacting, or curious about civil war cannons.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg,

by Stephen W. Sears (640 pages) (November 3, 2004). Description: Sears delivers another masterpiece with this comprehensive study of America’s most studied Civil War battle. Beginning with Lee's meeting with

Davis in May 1863, where he argued in favor of marching north, to take pressure off both Vicksburg and Confederate logistics. It ends with the battered Army

of Northern Virginia re-crossing the Potomac just two months later and with Meade unwilling to drive his equally battered

Army of the Potomac into a desperate pursuit. In between is the balanced, clear and detailed

story of how tens-of-thousands of men became casualties, and how Confederate independence on that battlefield was put forever

out of reach. The author is fair and balanced. Continued below...

He discusses

the shortcomings of Dan Sickles, who advanced against orders on the second day; Oliver Howard, whose Corps broke and was routed

on the first day; and Richard Ewell, who decided not to take Culp's Hill on the first night, when that might have been decisive.

Sears also makes a strong argument that Lee was not fully in control of his army on the march or in the battle, a view conceived

in his gripping narrative of Pickett's Charge, which makes many aspects of that nightmare much clearer than previous studies.

A must have for the Civil War buff and anyone remotely interested in American history.

Recommended Reading: Field Artillery Weapons of the Civil War,

revised edition (324 pages) (University of Illinois

Press). Description: "Field

Artillery Weapons of the Civil War" is the definitive reference work for civil war cannon used in the field. Nothing else

approaches its structured grouping and organization of the diverse and confused world of American Civil War field guns...

Recommended

Reading:

Civil War Heavy Explosive Ordnance: A Guide to Large Artillery Projectiles, Torpedoes, and Mines (Hardcover) (537

pages) (University of North Texas Press).

Description: The heavy ordnance is divided into two sections: large smoothbore projectiles, and rifled projectiles. The smoothbore

section is subdivided into: shot, shell and case shot; canister; and grape. Rifled projectiles are then subdivided into twenty-seven

major types and one miscellaneous group. Continued below...

The general form of each entry is a brief introduction of a page or several pages about the type (Archer,

Hotchkiss, Dyer, etc.) and then the following pages contain one to three images of each size and type of projectile of that

type. When three images of a given projectile are provided they are viewed straight on from top, bottom, and side. Some images

of shell or case are half sections. Entries below each set of photographs provide diameter, length, weight, gun, sabot, fuze,

rifling, rarity, provenance, and comments. RATED 5 STARS!

Recommended Reading: The 1864 Field Artillery Tactics: Instruction for Field Artillery (Hardcover)

(404 pages). Description: This guide provides the most thorough explanation of how Civil War artillery operated in the field;

definitions of all the equipment belonging to an artillery battery; explanations on the use of each piece of equipment; details

for handling the horses; movement of artillery; and formations for battle. The illustrations show the gun, ancillary equipment,

caissons and wagons, harnesses, ammunition types and how they are used, and emplacement positions. Includes all 39 artillery

bugle calls. Continued below...

Written by a board of officers (the Artillery Board of the Army), this version is authorized for use in

the training and employment of Union artillery. Also used by Confederate forces, the Confederate artillerist was trained on

and used the identical equipment as the Union forces. In fact, they relied extensively on captured Union artillery for their

training.

Recommended Reading: Brigades of Gettysburg: The Union

and Confederate Brigades at the Battle of Gettysburg (Hardcover) (704 Pages). Description: While the battle of Gettysburg is certainly the most-studied battle in American history, a comprehensive treatment

of the part played by each unit has been ignored. Brigades of Gettysburg

fills this void by presenting a complete account of every brigade unit at Gettysburg

and providing a fresh perspective of the battle. Using the words of enlisted men and officers, the author and renowned Civil War

historian, Bradley Gottfried, weaves a fascinating narrative of the role played by every brigade at the famous three-day battle,

as well as a detailed description of each brigade unit. Continued below...

Organized by

order of battle, each brigade is covered in complete and exhaustive detail: where it fought, who commanded, what constituted

the unit, and how it performed in battle. Innovative in its approach and comprehensive in its coverage, Brigades of Gettysburg is certain to be a classic and indispensable reference for the battle of Gettysburg

for years to come.

|