|

East Cemetery Hill

Battle of Gettysburg

Cemetery Ridge Battle of Gettysburg East Cemetery Hill

Seminary Ridge Battle of Gettysburg Map, General George Meade, General Robert E. Lee, General Winfield Scott Hancock, Battle

of Gettysburg Maps and History

East Cemetery Hill and Battle of Gettysburg

Cemetery Hill

The second day's battle of Gettysburg was the largest and costliest of the

three days. The second day’s fighting (at Devil’s Den, Little Round Top, The Wheatfield, The Peach Orchard, Cemetery

Ridge, Trostle Farm, Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill) involved at least 100,000 soldiers of which roughly 20,000 were

killed, wounded, captured or missing. The second day in itself ranks as the 10th bloodiest battle of the Civil War.

| Cemetery Hill from Steven's Knoll |

|

| Gettysburg NMP |

East Cemetery Hill, usually called Cemetery Hill, is one of the premier landmarks of the battlefield, situated

on the southern edge of Gettysburg overlooking the town and immediate area south of it. Originally known as "Raffensberger's

Hill", its better known name began in 1858 when Evergreen Cemetery was established on the summit. Both Union and Confederate

commanders referred to this height as Cemetery Hill during the battle. The first troops on the hill were those of General

O.O. Howard's Eleventh Corps, who arrived on the battlefield around noon of July 1st. Later that afternoon, General Winfield Scott Hancock, sent to the battlefield by General Meade, rallied Union troops here and re-organized the intermingled regiments after the fighting west and north of

town. Hancock and Howard both realized the strength of this position.

The hill was divided into small pastures, bordered on all sides with stone walls. General Howard placed

his Eleventh Corps troops behind these man-made defenses while artillerymen constructed earthen barricades or "lunettes",

for protection around their cannons, which were placed behind the infantrymen. By the morning of July 2nd, East Cemetery Hill

was one of the most heavily fortified positions on the field, its base ringed with infantry and three artillery batteries

crowning the summit. The western slope of Cemetery Hill, where the Soldiers National Cemetery is today, was also heavily fortified with infantry and artillery.

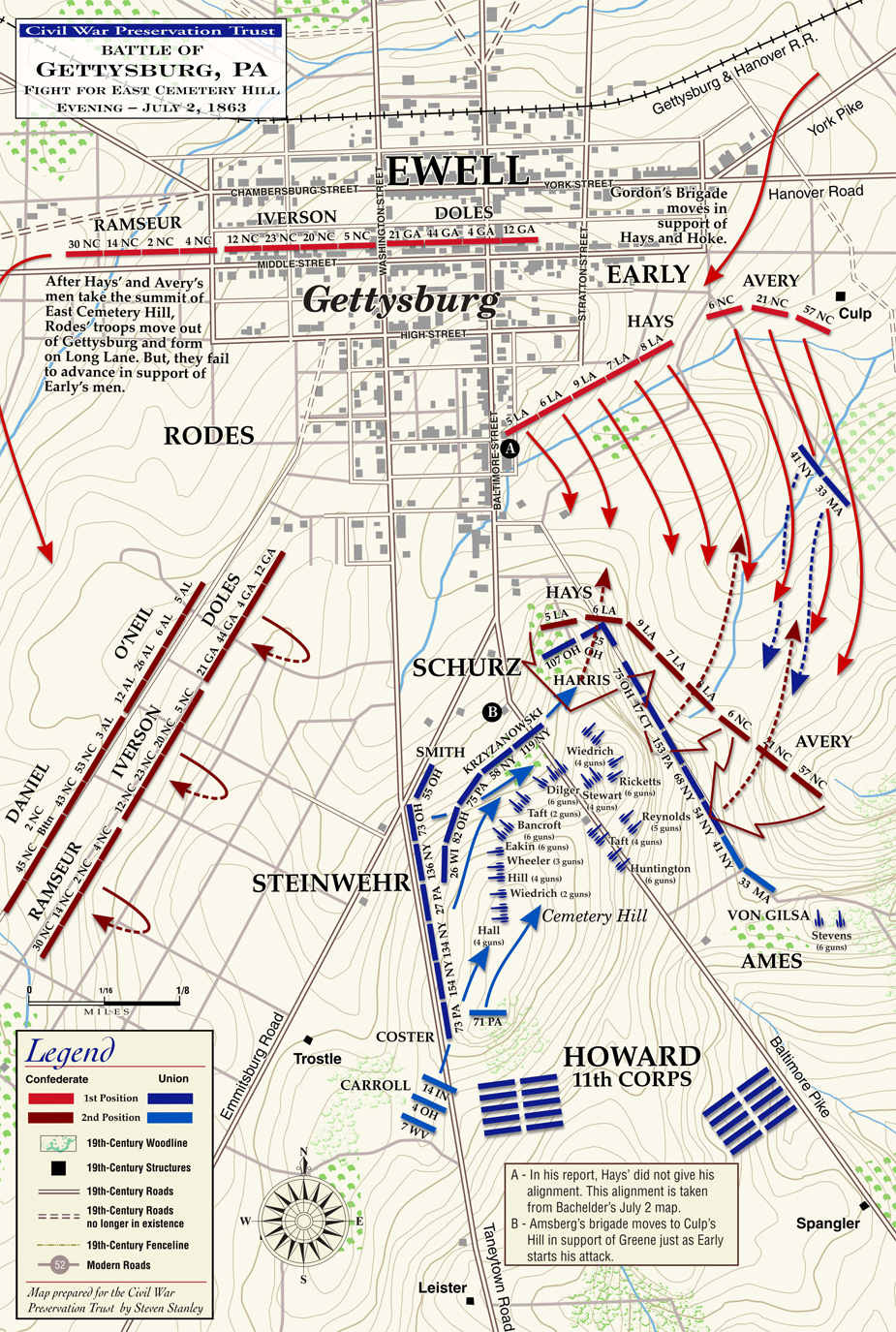

| East Cemetery Hill Battlefield, July 2, 1863 |

|

| Battle of East Cemetery Hill, July 2, 1863 |

(Right) The eastern slope of Cemetery Hill. Union infantry was posted in

the narrow lane at its base. Photo Gettysburg NMP.

Despite the hill's apparent invincibility, a Confederate attack briefly shattered the Union defenses here

on July 2. Soon after dusk, the Confederate brigades of General Harry Hays and Colonel Isaac Avery began their charge from

a stream bed on the Henry Culp Farm, crossing over a half-mile of rolling farmland, blocked out by low stone walls or high

rail fences, each an obstacle to the advancing Southerners. Many of these stone walls still exist today, leading up to the

eastern base of the hill that was bordered by a stone wall and narrow road filled with Union troops who were still shaken

from their disastrous experience of the day before. In the darkness, the men could hear the tramping of hundreds of feet in

the tall grass, the rattle of fence rails as they were pushed down, and the muffled commands of the Southern officers. Despite

heavy cannon fire directed against them, the Confederates reached the base of the hill and struck this first line of defense.

Wicked looking forms suddenly rose up in front of the Union soldiers, followed by the howling "Rebel Yell". Muzzle flashes

lit up the faces of combatants as hundreds of men suddenly found themselves face to face with the enemy. Confederates leapt

over the wall among the Union troops, shooting and clubbing around battle flags almost indistinguishable as to friend or foe

in the darkness and thick smoke.

(Left) The "Louisiana Tigers" broke the Union line at this point then charged

up this slope to attack the Union artillery in the center background. Photo Gettysburg

NMP.

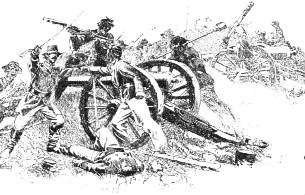

Union officers attempted to gain control of their troops to no avail; many paid little heed to their commands

and fled in near panic, running up the hill with members of the 6th, 7th, and 9th Louisiana Regiments, nicknamed "Louisiana

Tigers", in hot pursuit. At the summit, the Confederates rushed into the Union battery positions where artillerymen fought

back with everything at their disposal- rammers, pistols, rocks and fists. The fighting was hand to hand over the precious

guns. Major Samuel Tate of the 6th North Carolina wrote afterward that, "75 North Carolinians of the Sixth Regiment and 12

Louisianians of Hays' brigade scaled the walls and planted the colors of the Sixth North Carolina and Ninth Louisiana on the

guns. It was now fully dark. The enemy stood with tenacity never before displayed by them, but with bayonet, clubbed musket,

sword, pistol, and rocks from the wall, we cleared the heights and silenced the guns." Tate realized that his men were too

far extended and could not hold the hill without help, but there were none to be sent. Tate's command was on its own and time

was quickly running out for Union reserves were just then approaching East Cemetery Hill.

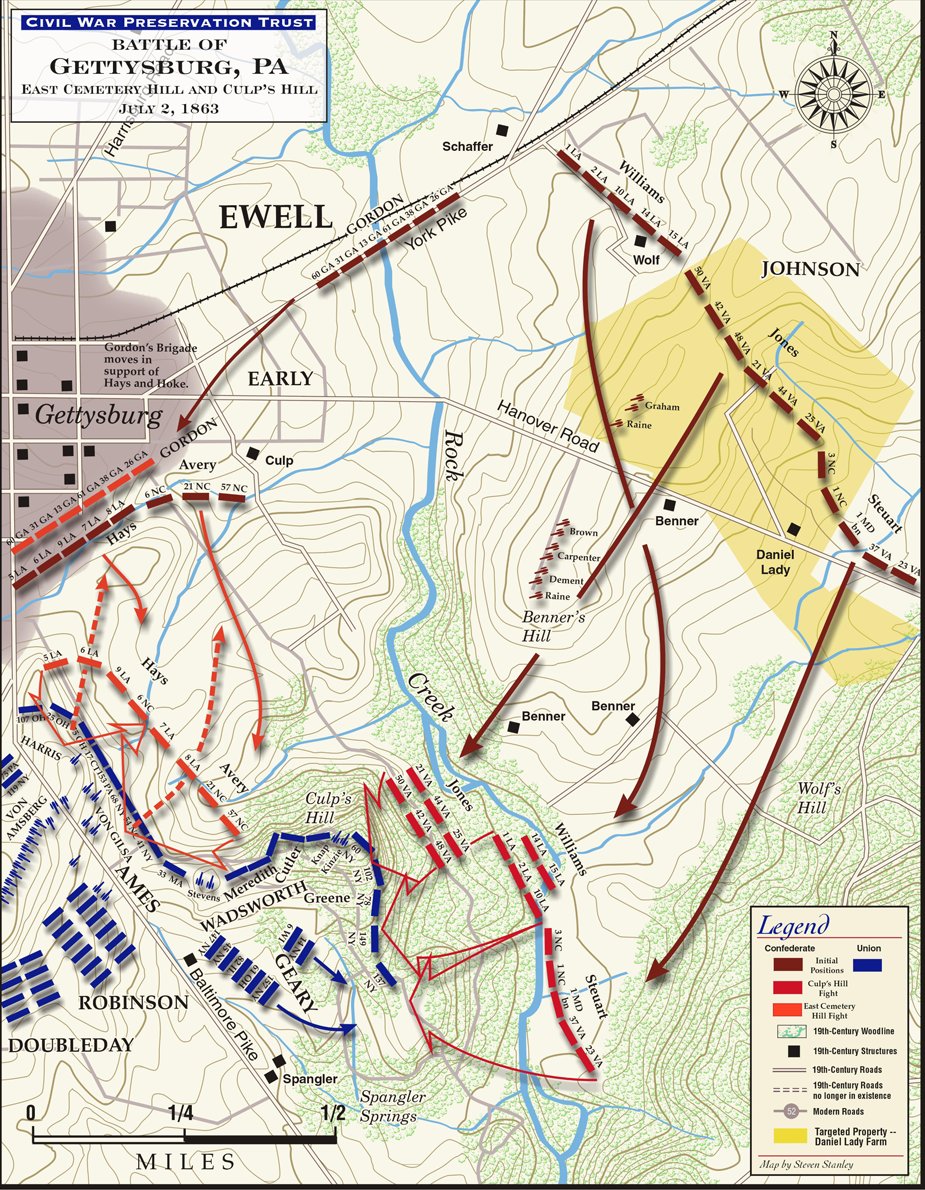

| East Cemetery Hill Battlefield, July 2, 1863 |

|

| Battle of East Cemetery and Culp's Hill, July 3, 1863 |

| The fight over Wiedrich's Battery on Cemetery Hill |

|

| Battles & Leaders |

From his location on Cemetery Ridge, General Hancock heard the roar of battle and immediately ordered Colonel Samuel S. Carroll's brigade of Ohio,

Indiana and West Virginia regiments from his own Second Corps, to rush to the hill. Carroll moved into the cemetery and formed

a battle line among the gravestones, while confusion reigned ahead. "We found the enemy up to and some of them among the...

batteries on the road," Carroll reported. "It being perfectly dark, and with no guide, I had to find the enemy's line entirely

by their fire. For the first few minutes they had a cross fire upon us from a stone wall... but, by changing the front of

the Seventh West Virginia, they were soon driven back from there." Carroll was forced to move his command regiment by regiment

into the fray. Colonel John Coons, at the head of the 14th Indiana, could discern a mass of Confederates on the crest of the

hill overtaking a cannon. "I immediately formed my regiment into line and advanced upon them with fixed bayonets, driving

them from the gun they had taken down the hill over a stone fence in front of the battery. At this point we gave them two

or three volleys, when they fell back. My regiment captured 1 stand of colors, 1 lieutenant-colonel, 1 major, 2 lieutenants,

and 14 privates." Troops from other sections of Cemetery Hill joined in the Union counterattack, which threw back the briefly

victorious Southerners. By midnight, Cemetery Hill was considered secure.

| Col. Isaac Avery |

|

| NC Regiments |

Losses for both sides were severe and among the seriously wounded was Colonel

Avery. The handsome North Carolinian was struck through the neck by a musket ball "in front of the heights" of Cemetery Hill,

where he was discovered after the charge by several of his soldiers and the 6th North Carolina's Major Tate. Tate knew the

wound was mortal and provided everything he could to make Avery's last hours comfortable as he lay dying in a field hospital.

Unable to speak, Avery scribbled a simple note for Tate: "Tell my father I died with my face to the enemy." Colonel Avery

died the following day. Command of the brigade was passed to Colonel A. C. Godwin who in his report eulogized his fellow officer:

"In his death the country lost one of her truest and bravest sons, and the army on of its most gallant and efficient officers."

Both flanks of the Union army had been attacked and both held. General Meade

discussed the day's events during a Council of War with his corps commanders that evening, and asked his generals for their opinions.

All agreed that the Cemetery Ridge position was very strong and to attack may prove folly. Without hesitation,

Meade ordered his army to stay and fight through the next day, retake the ground lost at Culp's Hill and wait for Lee's next move.

At his headquarters on Seminary Ridge, General Lee briefly conferred with his officers, among them his missing cavalry

chief, JEB Stuart who had arrived at headquarters that afternoon. Like Meade, Lee decided his army would not quit the battlefield

despite the setbacks he had suffered that afternoon. As he planned for another day of battle, he chose to continue with his

basic plan of attack and to strike Meade's defenses again, closer to what now might be his weakest area- the center of the

Union line.

The Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association

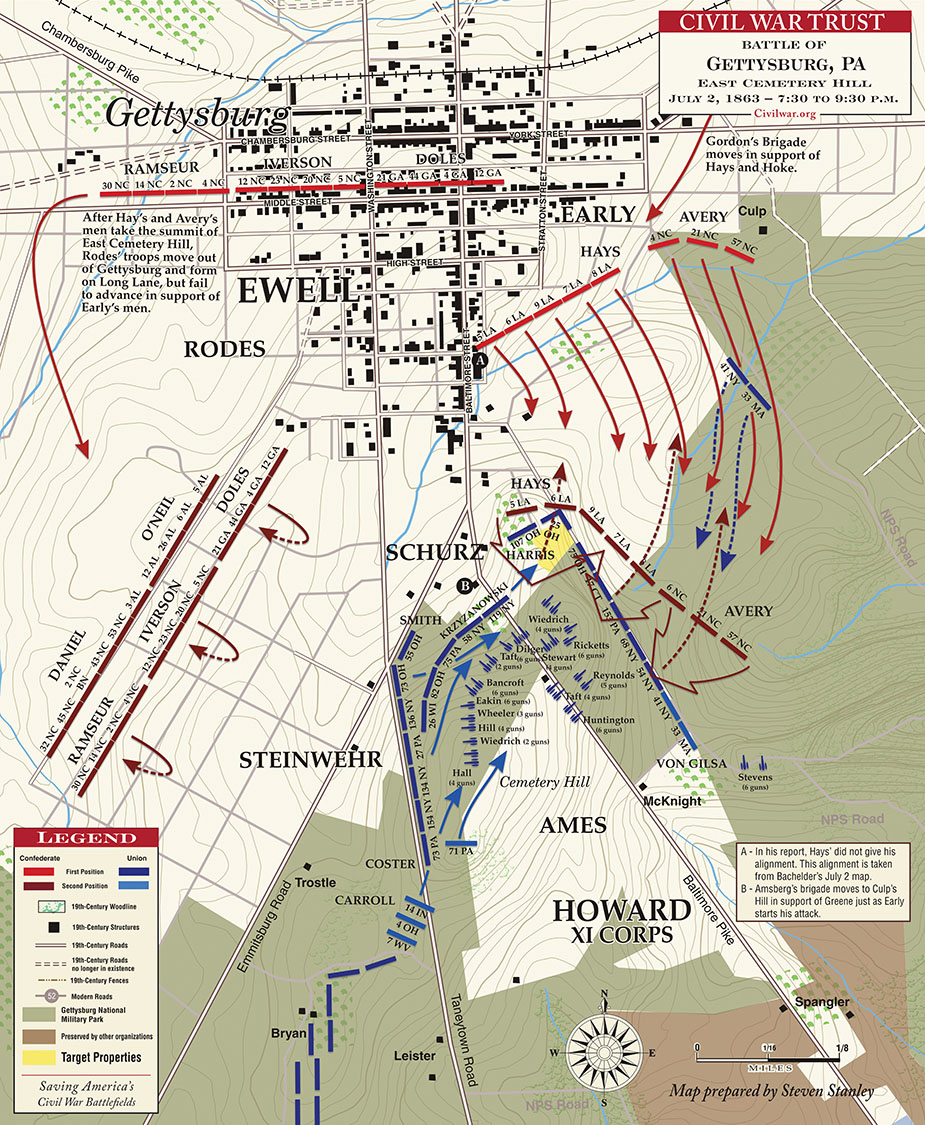

| East Cemetery Hill Battlefield, July 2, 1863 |

|

| Battle of East Cemetery Hill, July 2, 1863 |

(About) East Cemetery Hill map highlighting preservation efforts. Notice

the remaining 19th Century structures. Maps courtesy Civil War Trust. You are encouraged to support Civil War Trust, civilwar.org,

who is the nation's leader in preserving our country's Civil War battlefields. Civil War Trust is a nonpartisan, nonprofit

organization.

| GBMA tower on Cemetery Hill |

|

| Gettysburg NMP |

A few months after the close of the battle, a group of Gettysburg citizen's

intent on preserving the symbols of the Union sacrifice at Gettysburg organized the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association.

The group immediately set about raising funds to purchase key landmarks of the battlefield, especially those areas where Union

positions were still marked by earthworks and stone barricades. Some of these battle structures had been quickly removed by

farmers attempting to recover their land, yet many of the earthen barricades remained. The eastern half of Cemetery Hill was

one of the first prime areas purchased by the citizens group soon after the battle. Despite a lack of immediate funds, the

association landscaped this portion of Cemetery Hill, rebuilt the stone fences, planted grass, and preserved the artillery

lunettes. After the war, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association placed surplus cannon on stone pedestals in the artillery

positions and sponsored the construction of a wooden observation tower.

One of the board members was John B. Bachelder, the first official historian

of the Gettysburg battle. Bachelder was influential in spreading news about the association's efforts among veterans groups,

including the Society of the Army of the Potomac and the Grand Army of the Republic (or "GAR"), the national

organization of Union veterans. The Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association sponsored veteran gatherings and special events

at the park to help garner interest and collect donations. The Pennsylvania chapter of the GAR camped on the battlefield park

in 1877 and the veterans were delighted at what they found. It was through the influence of the chapter's leadership that

other state veteran organizations recommended Gettysburg as a mutual meeting ground, building to the first anniversary reunion

and encampment at the park in 1888 on the occasion of the 25th Anniversary of the battle.

The Battlefield Association purchased additional battlefield properties as

funds became available. More and more veterans began to visit the battlefield and an intense interest in improving the park

arose. Not only did Northerners visit the park, but many Southern veterans as well came to Gettysburg and walked the fields,

often accompanied by association guides.

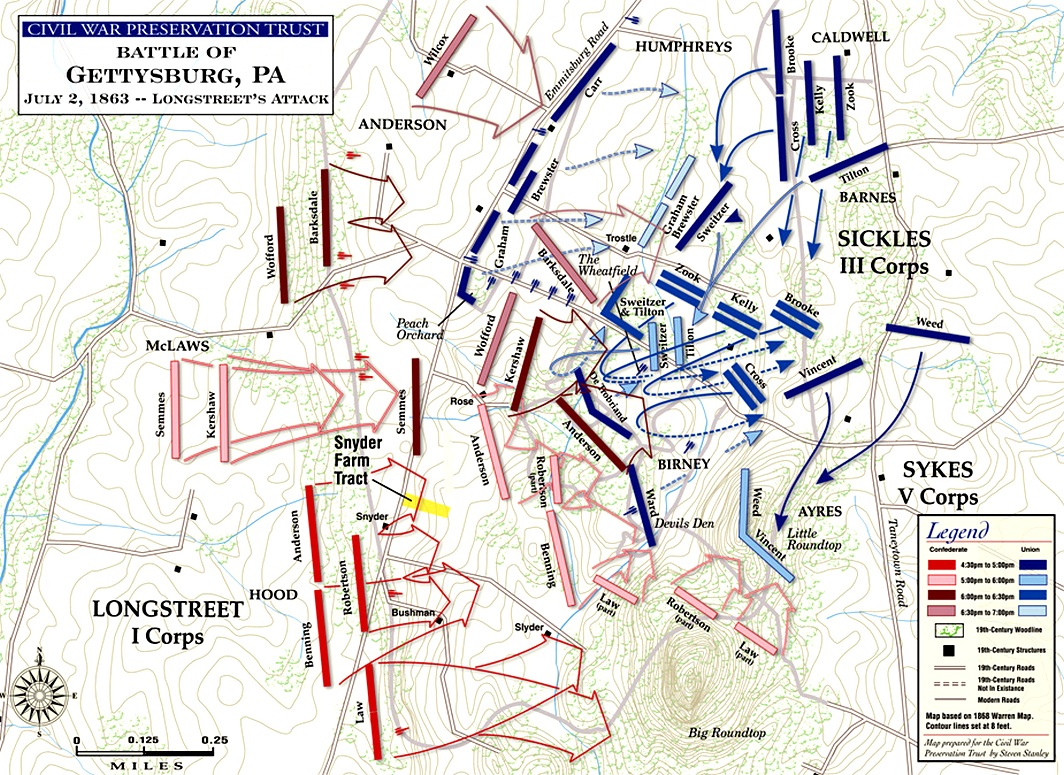

| Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

|

| Longstreet's Assault, Second Day, Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863 |

| GAR Encampment on East Cemetery Hill in 1878 |

|

| Gettysburg NMP |

By 1893, the association had gone about as far as it could with its limited funds and agreements. A number

of congressmen, most of them Civil War veterans, were highly interested in the battlefield and its preservation. Though groundwork

had been set for establishment of the first "National Military Park" at Chickamauga-Chattanooga in 1890, similar bills to

Federally secure Gettysburg had failed to get out of congressional committees. Then, in 1893, the battlefield was threatened

by the construction of an electric railway through portions of the park considered to be very significant. This threat pushed

congress into action. In December 1894, a bill was introduced in the United States Congress to officially establish Gettysburg

National Military Park, and it was signed into law the following February. Soon after, the GBMA lands were turned over to

the Federal government to be administered by a specially appointed commission of the United States War Department. In 1933,

jurisdiction of these Federal lands was turned over the National Park Service.

Sources: National Park Service; Gettysburg National Military Park; maps

courtesy Civil War Trust, civilwar.org.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg--The First Day,

by Harry W. Pfanz (Civil War America)

(Hardcover). Description: Though a great deal has been

written about the battle of Gettysburg, much of it has focused

on the events of the second and third days. With this book, the first day's fighting finally receives its due. Harry Pfanz,

a former historian at Gettysburg National

Military Park and author of

two previous books on the battle, presents a deeply researched, definitive account of the events of July 1, 1863. Continued below…

After sketching the background of the

Gettysburg

campaign and recounting the events immediately preceding the battle, Pfanz offers a detailed tactical description of the first

day's fighting. He describes the engagements in McPherson Woods, at the Railroad Cuts, on Oak

Ridge, on Seminary Ridge, and at Blocher's Knoll, as well as the retreat of Union forces through Gettysburg and the Federal rally on Cemetery Hill. Throughout, he draws on

deep research in published and archival sources to challenge some of the common assumptions about the battle--for example,

that Richard Ewell's failure to press an attack against Union troops at Cemetery Hill late on the first day ultimately cost

the Confederacy the battle.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg--Culp's Hill

and Cemetery Hill (Civil War America)

(Hardcover). Description: In this companion to his

celebrated earlier book, Gettysburg—The Second Day, Harry Pfanz provides the first definitive

account of the fighting between the Army of the Potomac and Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Cemetery Hill and

Culp's Hill—two of the most critical engagements fought at Gettysburg

on 2 and 3 July 1863. Pfanz provides detailed tactical accounts of each stage of the contest and explores the interactions

between—and decisions made by—generals on both sides. In particular, he illuminates Confederate lieutenant general

Richard S. Ewell's controversial decision not to attack Cemetery Hill after the initial Southern victory on 1 July. Continued

below...

Pfanz also

explores other salient features of the fighting, including the Confederate occupation of the town of Gettysburg,

the skirmishing in the south end of town and in front of the hills, the use of breastworks on Culp's Hill, and the small but

decisive fight between Union cavalry and the Stonewall Brigade. About the Author: Harry

W. Pfanz is author of Gettysburg--The First Day and Gettysburg--The

Second Day. A lieutenant, field artillery, during World War II, he served for ten years as a historian at Gettysburg National

Military Park and retired from the position of Chief Historian of the National Park Service in 1981. To purchase additional

books from Pfanz, a convenient Amazon Search Box is provided at the bottom

of this page.

Recommended

Reading:

Cemetery Hill: The Struggle For The High Ground, July 1-3, 1863. Description: Cemetery

Hill was critical to the Battle of Gettysburg. Controversy has ensued to the present day about the Confederacy's failure to

attempt to capture this high ground on July 1, 1863, following its victory over two Corps of the Union Army to the North and

West of town. Subsequent events during the Battle, such as

Pickett's charge, the fighting on Little Round Top, and the fight for the Wheatfield, have received more attention than General

Early's attack on Cemetery Hill during the evening of July 2. Yet, the fighting for Cemetery Hill was critical and may have

constituted the South's best possibility of winning the Battle of Gettysburg. Terry Jones's "Cemetery Hill: The Struggle for

the High Ground, July 1 -- 3, 1863" (2003) is part of a series called "Battleground America Guides" published by Da Capo Press.

Each volume in the series attempts to highlight a small American battlefield or portion of a large battlefield and to explain

its significance in a clear and brief narrative. Jones's study admirably meets the stated goals of the series. Continued below…

The book opens with a brief setting

of the stage for the Battle of Gettysburg. This is followed by chapters describing the Union and Confederate armies and the leaders who would play crucial roles in the fight

for Cemetery Hill. There is a short discussion of the fighting on the opening day of the battle, July 1, 1863, which focuses

on the failure of the South to attempt to take Cemetery Hill and the adjacent Culp's Hill following its victory of that day.

The chief subject of the book, however, is the fighting for Cemetery Hill late on July 2. Jones explains Cemetery Hill's role

in Robert E. Lee's overall battle plan. He discusses the opening artillery duel on the Union right followed by the fierce

attack by the Louisiana Tigers and North Carolina troops

under the leadership of Hays and Avery on East Cemetery Hill. This attack reached the Union batteries defending Cemetery Hill

and may have come within an ace of success given the depletion of the Union defense on the Hill to meet threats on the Union left. Elements of the Union 11th Corps and 2nd Corps reinforced

the position and drove back the attack. Southern general Robert Rodes was to have supported this attack on the west but failed

to reach his position in time to do so. General John Gordon's position was in reserve behind the troops of Hays and Avery

but these troops were not ordered forward. The book deals briefly with the third day of the Battle -- the day of Pickett's charge -- in which the Southern troops did not renew their

efforts against Cemetery Hill -- such an attempt would have had scant chance of success in daylight. The final chapter of

the book consists of Jones's views on the events of the battle, particularly the failure of the Lieutenant General Richard

Ewell of the Second Corps of Lee's Army to attack Cemetery Hill on July 1, a decision Jones finds was correct, and the causes

of the failure of the July 2 attack (poor coordination among Ewell, Rodes, Gordon, and A.P Hill of the Southern Third Corps.)

There is a brief but highly useful discussion to the prospective visitor to Gettysburg

of touring the Cemetery Hill portion of the Battlefield. The book is clearly, crisply and succinctly written. It includes

outstanding maps and many interesting photographs and paintings. The reader with some overall knowledge of Gettysburg will find this book more accessible that the two volumes of Harry Pfanz's outstandingly

detailed trilogy that deal with the first day of the battle and with the fighting for Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. Serious

students of the Battle of Gettysburg can get a good, clear overview of the fighting for Cemetery Hill from this volume.

Recommended Reading: Culp's Hill:

The Attack And Defense Of The Union Flank, July 2, 1863 (Battleground America).

Description: South of the town of Gettysburg, Union troops

take possession of the wooded heights at the tip of their "fishhook" defensive line. Defending Culp's Hill meant protecting

the flank; it was the key to victory. Using official reports, letters, diaries, and memoirs, this book describes the struggle

for the high ground and tells how and why the generals made their crucial decisions. "Cox tells this dramatic story with great

skill...Excellent narrative and analysis...Concisely written and informative." Continued below…

About the Author:

John D. Cox is a lifelong student of Gettysburg and a Licensed Battlefield Guide at Gettysburg

National Park. A veteran of the U.S. Air Force, he now spends his days

speaking at Civil War roundtables and giving tours at Gettysburg.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg, by Stephen

W. Sears (640 pages) (November 3, 2004). Description: Sears

delivers another masterpiece with this comprehensive study of America’s

most studied Civil War battle. Beginning with Lee's meeting with Davis in May 1863, where he

argued in favor of marching north, to take pressure off both Vicksburg

and Confederate logistics. It ends with the battered Army of Northern Virginia re-crossing the Potomac just two months later

and with Meade unwilling to drive his equally battered Army of the Potomac into a desperate

pursuit. In between is the balanced, clear and detailed story of how tens-of-thousands of men became casualties, and how Confederate

independence on that battlefield was put forever out of reach. The author is fair and balanced. Continued below...

He discusses

the shortcomings of Dan Sickles, who advanced against orders on the second day; Oliver Howard, whose Corps broke and was routed

on the first day; and Richard Ewell, who decided not to take Culp's Hill on the first night, when that might have been decisive.

Sears also makes a strong argument that Lee was not fully in control of his army on the march or in the battle, a view conceived

in his gripping narrative of Pickett's Charge, which makes many aspects of that nightmare much clearer than previous studies.

A must have for the Civil War buff and anyone remotely interested in American history.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. Description: America's Civil War raged for more than four years, but it is the three days of fighting in the Pennsylvania countryside in July 1863 that continues to fascinate, appall, and inspire new

generations with its unparalleled saga of sacrifice and courage. From Chancellorsville, where General Robert E. Lee launched

his high-risk campaign into the North, to the Confederates' last daring and ultimately-doomed act, forever known as Pickett's

Charge, the battle of Gettysburg gave the Union army a victory that turned back the boldest and perhaps greatest chance for

a Southern nation. Continued below...

Now, acclaimed

historian Noah Andre Trudeau brings the most up-to-date research available to a brilliant, sweeping, and comprehensive history

of the battle of Gettysburg that sheds fresh light on virtually every aspect of it. Deftly balancing his own

narrative style with revealing firsthand accounts, Trudeau brings this engrossing human tale to life as never before.

Recommended

Reading:

Lost Triumph: Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg--And Why It Failed.

Description: A fascinating narrative-and a bold new

thesis in the study of the Civil War-that suggests Robert E. Lee had a heretofore undiscovered strategy at Gettysburg that,

if successful, could have crushed the Union forces and changed the outcome of the war. The Battle of Gettysburg is the pivotal

moment when the Union forces repelled perhaps America's greatest commander-the

brilliant Robert E. Lee, who had already thrashed a long line of Federal opponents-just as he was poised at the back door

of Washington, D.C. It is

the moment in which the fortunes of Lee, Lincoln, the Confederacy, and the Union

hung precariously in the balance. Conventional wisdom has held to date, almost without exception, that on the third day of

the battle, Lee made one profoundly wrong decision. But how do we reconcile Lee the high-risk warrior with Lee the general

who launched "Pickett's Charge," employing only a fifth of his total forces, across an open field, up a hill, against the

heart of the Union defenses? Most history books have reported that Lee just had one very bad day. But there is much more to

the story, which Tom Carhart addresses for the first time. Continued below...

With meticulous

detail and startling clarity, Carhart revisits the historic battles Lee taught at West Point and believed were the essential

lessons in the art of war-the victories of Napoleon at Austerlitz, Frederick the Great at Leuthen, and Hannibal at Cannae-and

reveals what they can tell us about Lee's real strategy. What Carhart finds will thrill all students of history: Lee's plan

for an electrifying rear assault by Jeb Stuart that, combined with the frontal assault, could have broken the Union forces

in half. Only in the final hours of the battle was the attack reversed through the daring of an unproven young general-George

Armstrong Custer. About the Author: Tom Carhart has been a lawyer and a historian for the Department of the Army in Washington, D.C. He is

a graduate of West Point, a decorated Vietnam veteran, and has earned a

Ph.D. in American and military history from Princeton University. He is the author of four books of military history and teaches at Mary Washington College

near his home in the Washington, D.C.

area.

Recommended Reading: The Artillery of Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description:

The battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the apex of the Confederacy's

final major invasion of the North, was a devastating defeat that also marked the end of the South's offensive strategy against

the North. From this battle until the end of the war, the Confederate armies largely remained defensive. The Artillery of

Gettysburg is a thought-provoking look at the role of the artillery during the July 1-3, 1863 conflict. Continued below...

During the

Gettysburg

campaign, artillery had already gained the respect in both armies. Used defensively, it could break up attacking formations

and change the outcomes of battle. On the offense, it could soften up enemy positions prior to attack. And even if the results

were not immediately obvious, the psychological effects to strong artillery support could bolster the infantry and discourage

the enemy. Ultimately, infantry and artillery branches became codependent, for the artillery needed infantry support lest

it be decimated by enemy infantry or captured. The Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had modified its codependent command

system in February 1863. Prior to that, batteries were allocated to brigades, but now they were assigned to each infantry

division, thus decentralizing its command structure and making it more difficult for Gen. Robert E. Lee and his artillery

chief, Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, to control their deployment on the battlefield. The Union Army of the Potomac

had superior artillery capabilities in numerous ways. At Gettysburg,

the Federal artillery had 372 cannons and the Confederates 283. To make matters worse, the Confederate artillery frequently

was hindered by the quality of the fuses, which caused the shells to explode too early, too late, or not at all. When combined

with a command structure that gave Union Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt more direct control--than his Southern counterpart had over

his forces--the Federal army enjoyed a decided advantage in the countryside around Gettysburg. Bradley

M. Gottfried provides insight into how the two armies employed their artillery, how the different kinds of weapons functioned

in battle, and the strategies for using each of them. He shows how artillery affected the “ebb and flow” of battle

for both armies and thus provides a unique way of understanding the strategies of the Federal and Union

commanders.

|