|

MILITARY AND NINETEENTH CENTURY OKLAHOMA

More than any other part of the United States, Oklahoma was the product of

military intervention. The U.S. Army was a major factor in the development of Oklahoma from the United States' acquisition

of the area in 1803 to the last land run in 1893. It is possible to distinguish at least seven phases in the story of the

military's presence and activity in the state.

The first phase, 1803-19, was largely a time of exploration, which began with

the purchase of the vaguely defined territory of "Louisiana" from France. By the late 1810s the federal government had decided to use much of the new territory as a resettlement area

for eastern Indians, while permitting non-Indian settlement immediately west of the Mississippi River. The first eastern Indians

to be relocated were some Cherokee, who, beginning in 1808, voluntarily emigrated to what soon became western Arkansas. There was violent competition between

the Cherokee and the local Osage over hunting grounds. The army attempted to stem the bloodshed by establishing Fort Smith

(1817) on the Arkansas River. As the fort's location was part of Oklahoma until it was transferred to Arkansas in 1905, Fort

Smith may be considered the first U.S. military post in present Oklahoma.

The second phase of the army's presence, 1819-30, witnessed the creation of

a so-called "permanent Indian frontier." The Indians of the newly created territories of Missouri (1816) and Arkansas (1819)

were displaced west of their boundaries. Then, between 1819 and 1827, a line of seven new military posts, reaching from present

Minnesota to the state of Louisiana, was established. The posts were in part intended to reassure territorial settlers. However,

the most active of the forts were those assigned to keep the peace between the Indians who had been relocated and the Indian

nations that were already resident west of the frontier.

The military's activity in Oklahoma

intensified in the third phase, 1830-48, which began with the Indian Removal Act and ended with the conclusion of the Mexican

War. During the 1830s, Pres. Andrew Jackson signed nearly seventy Indian removal treaties. These required the nations that had

supposedly agreed to relocation to migrate to the "Indian Country" or "Indian Territory" in the West. Most of the Indians were directed to the present states of Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma. As removal was partially carried out by coercion, the army was called upon to enforce the removals.

Several of the treaties obligated the United States to provide protection

for the "removed" eastern Indians from the "wild Indians" of the Plains. The relocated Indians also had to deal with outlaws

and whiskey runners from Arkansas and with brigands and horse thieves from the American colonies within Mexican Tejas (the

independent Republic of Texas after 1836). Conversely, Comanche and Kiowa raiders began to use "Indian territory" as a refuge after preying on the American

settlements in Tejas/Texas. In response to the various demands for protection, the U.S. Army reestablished Forts Gibson and

Smith and founded Forts Coffee (1834), Wayne (1838), and Washita (1842). A system of military roads, the first genuine roads

in today's Oklahoma, were blazed to connect such posts.

During the 1830-48 phase of military activity, soldiers took part in four

expeditions in the Oklahoma portion of Indian territory. All of these efforts were partially intended to further the work

of the Stokes Commission. The commission, established in 1832 by the secretary of war, sought to discourage the raiding of

removed eastern Indians by Plains Indians. Capt. Jesse Bean's 1832 expedition of volunteer "mounted riflemen" and Capt. James

B. Many's 1833 expedition of infantry and riflemen failed to make contact with the Plains nations they sought. However, Capt.

Henry Dodge's "Dragoon Expedition" of 1834 (dragoons are heavily armed, mounted troops) was able to persuade some Kiowa, Comanche,

and Wichita in southwestern Oklahoma to meet with U.S. representatives. The Dragoon Expedition was significant as the first

major mounted military expedition in U.S. history. A year later the Stokes Commission sent out Maj. Richard B. Mason with

another party of dragoons. The 1835 Treaty of Camp Holmes secured by the Mason Expedition was the first U.S. treaty with southern

Plains or southwestern Indians.

At least two of the expeditions mentioned above were also concerned

with protecting the burgeoning trade with the Mexican province of Nuevo Mexico via the Santa Fe Trail. Some of the Indians

engaged in raiding the caravans were based in what is now western Oklahoma. The Many Expedition doubled as a show of strength

after an attack on a party of U.S. traders. The Mason Expedition attempted to secure a promise that the Plains Indians

would not make further raids on traders. The expeditions of 1832-35 provided training for the U.S. Army units that fought

in the Mexican War more than a decade later.

The fourth phase of military engagement

in Oklahoma, 1848-61, took place between the end of the war with Mexico and the beginning of the Civil War. This period

was one of intensified settlement in the new state of Texas (December 29, 1845) and the new territories of Nebraska and Kansas

(1854). Today's Oklahoma was the recipient of the Indian populations of Kansas, Nebraska, and Texas as they were forced out.

There was, accordingly, an increasing tendency to refer to present Oklahoma as the Indian Territory. Once again, the army

was called upon to be an instrument of coercion in Indian removal. As the fiction of the "permanent Indian frontier" disappeared,

Forts Gibson and Towson were closed. In their place came Fort Cobb (1859), which received Indians from Texas, and Fort Arbuckle

(1851). The latter post sought to protect the Choctaw and Chickasaw, as well as overland emigrants, from increasingly numerous

raids by Kiowa and Comanche holdouts in Texas.

| Oklahoma Civil War Map of Battles |

|

| Oklahoma Civil War Battlefields) |

A strategic connection was now developing between the posts in present Oklahoma

and those in Texas. Indian Territory forts were linked by road to a first (1849) line and then a second (early 1850s) line

of "Comanche frontier" defenses in Texas. In 1858 most of the future state of Oklahoma became part of the U.S. Army's Department

of Texas. That same year two campaigns were launched from Texas against Comanche and Kiowa operating out of Oklahoma. Texas

Rangers led by John S. "Rip" Ford on May 12 struck Indians concealed near the Antelope Hills of western Oklahoma. On October

1 the Second Cavalry Regiment under Capt. Earl Van Dorn attacked a Comanche band encamped on Rush Springs Creek in southern

Oklahoma. (Unknown to Van Dorn, the band's leader, Buffalo Hump, had traveled from Texas to discuss peace terms with the commander

of Fort Arbuckle.)

The army was also committed to protecting non-Indian wayfarers who passed

through present Oklahoma. These included emigrants traveling the Texas Road and, later, passengers of the Butterfield Overland

Mail and stage line. In 1849 a small command under Capt. Randolph B. Marcy was ordered to accompany a party of emigrants and

prospectors from Arkansas as far as New Mexico. The Marcy Expedition's more important objective was to determine the feasibility

of a central route for a national road.

Westward emigration and Plains Indian warfare necessitated the expansion of

the peacetime army. The military experience in Oklahoma had done much to make this need evident, particularly the need for

more mounted troops. In 1855 the army was expanded by two infantry regiments and two cavalry regiments. The latter were "true"

cavalry, adapted for mobility, versus the dragoon and mounted riflemen regiments from which they evolved. The army was further

expanded in the 1850s through the 1870s by the recruitment of Indian Territory Indians as guides, translators, and other auxiliaries.

The practice of pitting Indians against Indians reached its peak in the next

phase of military activity, the American Civil War of 1861-65. Several factors drew the Indian nations of present Oklahoma

into this conflict. One was the hope that siding with the United States or the Confederacy might increase the prospects of

preserving the Indian Territory nations from being dissolved. Another consideration was the opportunity to settle long-standing

political and familial rivalries. A third factor was concern over the withdrawal of the protective garrisons in Indian Territory

so that the troops might take part in the campaigns east of the Mississippi River. This transfer was accompanied by the wartime

suspension of promised annuity payments.

Confederate Indian Commissioner Albert Pike skillfully played upon the resentments

felt by many Indians toward the United States. He was thus able to negotiate alliances with factions of ten Indian nations.

The defense of Indian Territory against outlaws and Plains Indian raiders was left to either Confederate troops and Texas

frontier guards or to volunteer regiments from Union states and territories. However, the principal target of the Confederate

and Federal units was not marauders, but each another.

Indian troops faced off in the important campaigns within present Oklahoma.

The first major encounter was the aborted Union Indian Expedition of summer 1862. Another Union effort in 1863, which culminated

in the Honey Springs campaign, was successful. Most Confederate sympathizers and allies were driven south of the Arkansas

River. This was followed by the Texas Road operations of 1864, which succeeded in dispersing many of the Confederate Indians

in the southern part of the territory.

During the war, around 5,000 Indian Territory Indians were recruited into

eleven Confederate Indian regiments and eight battalions. On the opposing side, about 3,350 Indians joined three Indian Home

Guard regiments. The Indian military experience in the Civil War became an important factor in Indian assimilation within

Euroamerican society. For one thing, many Indians joined or fought alongside non-Indian volunteer regiments from states and

territories that adjoined Indian Territory. For another, the Indians' treaties with the Confederacy provided the U.S. government

with an excuse to impose the Reconstruction Treaties of 1866. These postwar treaties were a blow to Indian autonomy and to

Indian territorial integrity.

The sixth phase of military activity in Indian Territory, 1865-75, extended

from the close of the Civil War to the end of the Red River War. This period saw the concentration of the southern Plains

tribes within Indian Territory and the Plains Indians' resistance to the reservation system. During and following the Civil

War the southern Plains Indians experienced many grievances. Gold prospectors had continued to travel through their hunting

grounds even during the war. Some of those same miners participated in the infamous Sand Creek Massacre of Southern Cheyenne

in Colorado in 1864. By 1867 the new states of Kansas and Nebraska successfully demanded the expulsion of nearly all Indians

from their borders. Railroads and cattle trails further violated lands claimed by the Plains peoples. A rapid postwar increase

in non-Indian settlement on the Plains also increased opportunities to carry out the Indian tradition of raiding.

The Department of the Interior's optimistic response to the growing friction

was a series of treaties negotiated at Medicine Lodge Creek, Kansas, with a minority of Indian leaders. These 1867 treaties

authorized Cheyenne-Arapaho and Kiowa-Comanche reservations in present Oklahoma. From the outset, the new reservations were

plagued by administrative corruption, the depletion of game and grazing, and the inability of the army to prevent incursions

by horse thieves, cattlemen, and hunters.

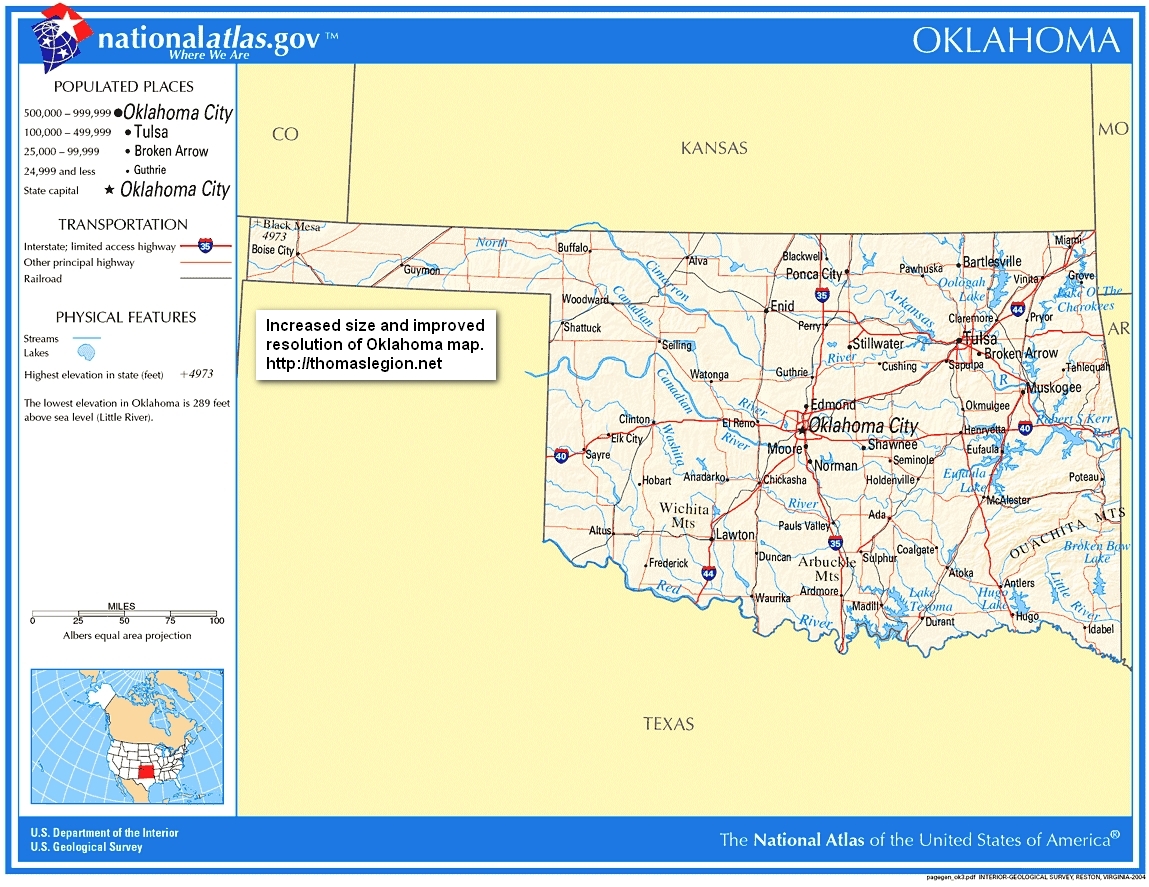

| State of Oklahoma Map |

|

| Present-day Map of Oklahoma |

The treaties were soon followed by a renewal of Southern Cheyenne assaults

in Kansas and Nebraska. These attacks coincided with Kiowa and Comanche raids into Texas and Kansas from the haven of the

new Plains Indian reservations in Indian Territory. The commander of the U.S. Army's Division of the Missouri, which included

much of the Great Plains, was Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan. Sheridan met the violence with the West's first major winter campaign.

A column under Lt. Cols. Alfred Sully and George A. Custer departed Kansas to establish a campaign base camp, Camp Supply,

in northwestern Indian Territory. On November 27, 1868, Custer attacked a Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne camp on the

Washita River. Tragically, it proved to be the encampment of a "peace chief," Black Kettle. The strike did, however, manage

to demoralize many of the more aggressive Cheyenne and Arapaho. Led by Maj. Andrew W. Evans, another column out of New Mexico

surprised a Comanche village at Soldier Spring on Christmas Day 1868. Evans's victory in westernmost Indian Territory encouraged

several hostile Indian bands to disperse.

As increasing numbers of Indians capitulated on the reservations, Fort Sill

(1869) was established to keep watch on the Comanche-Kiowa Agency and Fort Reno (1875) to guard the Cheyenne-Arapaho Agency.

The founding of Fort Sill proved timely, as there was a resurgence of Kiowa and Cheyenne raiding by 1871. The conflict this

time was aggravated by the incursions of buffalo hide hunters into traditional Indian hunting areas and by a prohibition against

the army pursuing Indian raiders onto the reservations. The violence escalated into the Red River War of 1874-75.

The Red River War was the greatest Indian war fought in Indian Territory.

To win the conflict, Sheridan planned a five-pronged invasion of the hostile Comanche and Kiowa stronghold in the Texas Panhandle

for autumn and winter of 1874-75. One of the columns originated at Fort Sill. Of the fourteen engagements fought during the

war, three took place in present Oklahoma. By June 1875 the last of the belligerent leaders had surrendered to officials on

the Comanche-Kiowa Reservation. By then more than seventy war leaders had been arrested for transfer to a military prison

in Florida. Near the Darlington or Cheyenne-Arapaho Agency, a Southern Cheyenne warrior named Black Horse broke and ran while

being shackled. Panic set in among others in the vicinity, and this resulted in a stiff engagement known as the "Sand Hill

Fight" on April 6, 1875.

The last Indian conflicts and the end of the reservation system were the first

major events of the last phase of military activity, 1875-93. A relocation of Northern Cheyenne to the overtaxed Cheyenne-Arapaho

Reservation resulted in a Northern Cheyenne flight from Indian Territory. The initial pursuit of Dull Knife's and Little Wolf's

bands in 1877 was the last significant event in Indian warfare in present Oklahoma.

In 1887 the Dawes Severalty Act called for an end to reservations. The act

established the Dawes Commission (not created until 1893), which broke up the communal reservations and distributed individual

land allotments. The measure created considerable distress, as it destroyed traditional Indian life and invited land fraud.

Called upon to deal with any violent resistance with the allotment process,

the army also found itself in another law enforcement role as it attempted to capture David Payne's "Boomers." Between 1882

and 1885 cavalry detachments were repeatedly dispatched to capture these armed parties of squatters and escort them back to

Kansas. But the would-be settlers' demand for free land finally succeeded. As a result, the army was in 1889 made responsible

for regulating the Unassigned Lands land run in central Oklahoma. The army was again called upon to prevent fraud by "Sooners"

and claim jumpers during the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation run of 1892 and the Cherokee Outlet land run of 1893. Overseeing

the 1893 land run represented the last duty of the old frontier army.

(Sources listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended

Reading: Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right (Critical Issue Book). From Booklist:

In this concise essay, Stephanson explores the religious antecedents to America's

quest to control a continent and then an empire. He interprets the two competing definitions of destiny that sprang from the

Puritans' millenarian view toward the wilderness they settled (and natives they expelled). Here was the God-given chance to

redeem the Christian world, and that sense of a special world-historical role and opportunity has never deserted the American

national self-regard. But would that role be realized in an exemplary fashion, with America

a model for liberty, or through expansionist means to create what Jefferson called "the empire

of liberty"? Continued below…

The antagonism

bubbles in two periods Stephanson examines closely, the 1840s and 1890s. In those times, the journalists, intellectuals, and

presidents he quotes wrestled with America's purpose in fighting each decade's war, which added

territory and peoples that somehow had to be reconciled with the predestined future. …A sophisticated analysis of American

exceptionalism for ruminators on the country's purpose in the world.

Recommended

Reading: Seizing Destiny: The Relentless Expansion of American

Territory. From Publishers Weekly: In an admirable and important addition to his distinguished oeuvre,

Pulitzer Prize–winner Kluger (Ashes to Ashes, a history of the tobacco wars) focuses on the darker side of America's

rapid expansion westward. He begins with European settlement of the so-called New World, explaining that Britain's successful colonization depended not so much on

conquest of or friendship with the Indians, but on encouraging emigration. Kluger then fruitfully situates the American Revolution

as part of the story of expansion: the Founding Fathers based their bid for independence on assertions about the expanse of

American virgin earth and after the war that very land became the new country's main economic resource. Continued below...

The heart of

the book, not surprisingly, covers the 19th century, lingering in detail over such well-known episodes as the Louisiana Purchase

and William Seward's acquisition of Alaska. The final chapter looks at expansion in the 20th century. Kluger

provocatively suggests that, compared with western European powers, the United States

engaged in relatively little global colonization, because the closing of the western frontier sated America's expansionist hunger. Each chapter of this long, absorbing book is rewarding

as Kluger meets the high standard set by his earlier work. Includes 10 detailed maps.

Recommended

Reading: Manifest Destiny and Mission in American

History (Harvard University Press). Description: "Before this book first appeared in 1963, most historians wrote as if the continental expansion of

the United States was inevitable. 'What

is most impressive,' Henry Steele Commager and Richard Morris declared in 1956, 'is the ease, the simplicity, and seeming

inevitability of the whole process.' The notion of 'inevitability,' however, is perhaps only a secular variation on the theme

of the expansionist editor John L. O'Sullivan, who in 1845 coined one of the most famous phrases in American history when

he wrote of 'our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence

for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.' Continued below...

Frederick Merk rejected inevitability in favor of a more contingent interpretation

of American expansionism in the 1840s. As his student Henry May later recalled, Merk 'loved to get the facts straight.'" --From the Foreword by John Mack Faragher About the Author: Frederick Merk was Gurney

Professor of American History, Harvard University.

Recommended

Reading: What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford History of the United States) (Hardcover: 928 pages). Review: The

newest volume in the renowned Oxford History of the United States-- A brilliant portrait of an era that saw dramatic transformations

in American life The Oxford History of the United States

is by far the most respected multi-volume history of our nation. The series includes two Pulitzer Prize winners, two New York

Times bestsellers, and winners of the Bancroft and Parkman Prizes. Now, in What Hath God Wrought, historian Daniel Walker

Howe illuminates the period from the battle of New Orleans to the end of the Mexican-American

War, an era when the United States expanded

to the Pacific and won control over the richest part of the North American continent. Continued below…

Howe's panoramic

narrative portrays revolutionary improvements in transportation and communications that accelerated the extension of the American

empire. Railroads, canals, newspapers, and the telegraph dramatically lowered travel times and spurred the spread of information.

These innovations prompted the emergence of mass political parties and stimulated America's economic development from

an overwhelmingly rural country to a diversified economy in which commerce and industry took their place alongside agriculture.

In his story, the author weaves together political and military events with social, economic, and cultural history. He examines

the rise of Andrew Jackson and his Democratic party, but contends that John Quincy Adams and other Whigs--advocates of public

education and economic integration, defenders of the rights of Indians, women, and African-Americans--were the true prophets

of America's future. He reveals the power

of religion to shape many aspects of American life during this period, including slavery and antislavery, women's rights and

other reform movements, politics, education, and literature. Howe's story of American expansion -- Manifest Destiny -- culminates

in the bitterly controversial but brilliantly executed war waged against Mexico

to gain California and Texas for the United States. By 1848, America had been transformed. What Hath God Wrought provides a monumental narrative

of this formative period in United States

history.

Recommended

Reading: The Impending Crisis,

1848-1861 (Paperback), by David M. Potter.

Review: Professor Potter treats an incredibly complicated and misinterpreted time period with

unparalleled objectivity and insight. Potter masterfully explains the climatic events that led to Southern secession –

a greatly divided nation – and the Civil War: the social, political and ideological conflicts; culture; American

expansionism, sectionalism and popular sovereignty; economic and tariff systems; and slavery. In other words, Potter places under the microscope the root causes and origins of the Civil War. He conveys

the subjects in easy to understand language to edify the reader's understanding (it's not like reading some dry

old history book). Continued below…

Delving beyond

surface meanings and interpretations, this book analyzes not only the history, but the historiography of the time period as

well. Professor Potter rejects the historian's tendency to review the period with all the benefits of hindsight. He simply

traces the events, allowing the reader a step-by-step walk through time, the various views, and contemplates the interpretations

of contemporaries and other historians. Potter then moves forward with his analysis. The Impending Crisis is the absolute

gold-standard of historical writing… This simply is the book by which, not only other antebellum era books, but all

history books should be judged.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Brad Agnew, Fort Gibson: Terminal on the Trail of Tears (Norman:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1980). Edwin C. Bearss and Arrell M. Gibson, Fort Smith: Little Gibraltar on the Arkansas (2d

ed.; Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1979). William Y. Chalfant, Without Quarter: The Wichita Expedition and the Fight

on Crooked Creek (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991). Peter Cozzens, ed., Eyewitnesses to the Indian War, 1865-1890,

Vol. 3., Conquering the Southern Plains (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 2003). LeRoy H. Fischer, ed., The Civil War

Era in Indian Territory (Los Angeles: L. L. Morrison, 1974). Grant Foreman, Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized

Tribes of Indians (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953). William H. Goetzmann, Army Exploration in the American West,

1803-1863 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959). Jerome A. Greene, Washita: The U.S. Army and the Southern Cheyennes, 1867-1869

(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004). Stan Hoig, The Battle of the Washita: The Sheridan-Custer Indian Campaign of

1867-69 (1976; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979). Stan Hoig, Fort Reno and the Indian Territory Frontier

(Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000). Stan Hoig, Perilous Pursuit: The U.S. Cavalry and the Northern Cheyennes

(Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2002). Michael Hughes, "Nations Asunder, Part II: Reservation and Eastern Indians

During the American Civil War, 1861 1865," Journal of the Indian Wars 1: 4 (2000). David La Vere, Contrary Neighbors: Southern

Plains and Removed Indians in Indian Territory (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000). John H. Monnett, Tell Them We

Are Going Home: The Odyssey of the Northern Cheyennes (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001). Wilbur S. Nye, Carbine

and Lance: The Story of Old Fort Sill (3d ed., rev.; Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969). Francis Paul Prucha, The

Sword of the Republic: The United States Army on the Frontier, 1783-1846 (1969; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,1986).

Robert M. Utley, Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891 (1973; reprint, Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 1984). Robert M. Utley, Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848-1865 (1967; reprint,

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981). Robert Wooster, The Military and United States Indian Policy, 1865-1903 (Lincoln:

University of Nebraska Press, 1988).

Michael A. Hughes

© Oklahoma Historical Society

|