|

[From the Richmond, Va., Times-Dispatch, February 7,

1904.]

PICKETT'S CHARGE.

The Story of It as Told by a Member of His Staff

CAPTAIN ROBERT A. BRIGHT.

Statements to Where the General Was During the

Charge.--Why the Attack Failed.

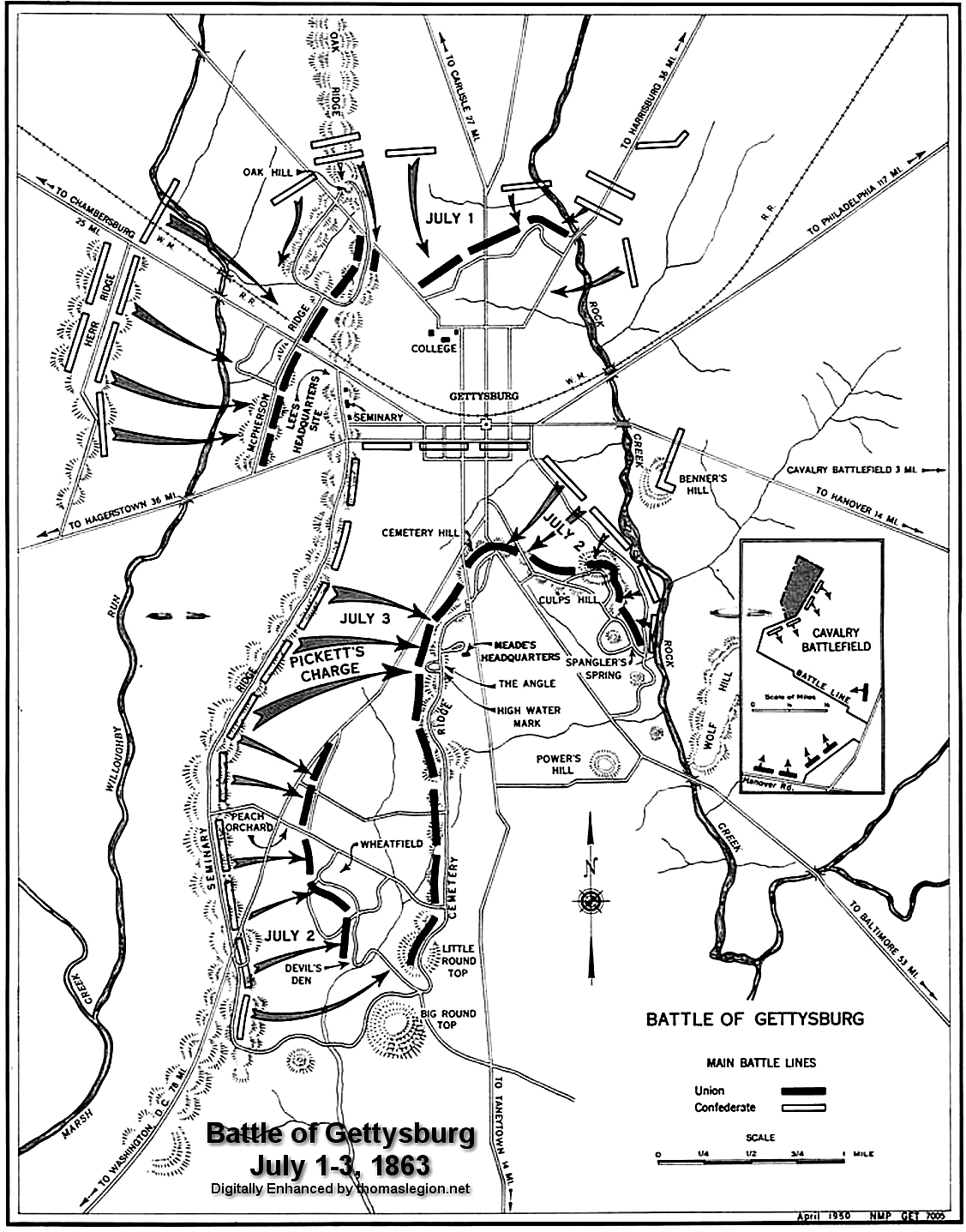

| Gettysburg Battlefield Map |

|

| Pickett's Charge and Battle of Gettysburg |

The following statement of what I saw and heard on the third day

at Gettysburg was in the main written about thirty years ago, and was rewritten for publication in 1903, but the issue of

it was prevented until now by an attack of gout, from which I suffered. I earnestly wish that it had come out before the death

of my corps commander, the brave General Longstreet.

Early in the morning Pickett's Virginians, forty-seven hundred muskets, with

officers added, five thousand strong, moved from the camping ground of the second day, two miles in rear, to the battlefield,

and took position behind the hill from which we charged later in the day. Then came the order from headquarters: "Colonel

E. P. Alexander will command the entire artillery in action to-day, and Brigadier-General Pendleton will have charge of the

reserve artillery ammunition of the army." Later, General Pickett was informed from General Longstreet's headquarters that

Colonel Alexander would give the order when the charge should begin. Several hours later the batteries on both sides opened.

Had this occurred at night, it would have delighted the eye more than any fire works ever seen.

ENGLISH GORDON.

Shortly before the artillery duel commenced, I returned from looking over

the ground in our front, and found General Pickett talking to a strange officer, to whom he introduced me saying: "This is

Colonel Gordon, once opposed to me in the San Juan affair, but now on our side."

In explanation of this I will state here that the San Juan affair occurred

on the Pacific coast when General Pickett was captain in the United States army, and when he held the island against three

English ships of war and 1,000 English regulars, he having one company of United States infantry and part of another company.

General Winfield Scott was sent out by this government to settle the trouble.

After the introduction, Colonel Gordon, who was an Englishman, continued speaking

to General Pickett, and said:

"Pickett, my men are not going up to-day."

The General said--

"But, Gordon, they must go up; you must make them go up."

Colonel Gordon answered:

"You know, Pickett, I will go as far with you as any other man, if only for

old acquaintance sake, but my men have until lately been down at the seashore, only under the fire of heavy guns from ships,

but for the last day or two they have lost heavily under infantry fire and are very sore, and they will not go up to-day."

This officer was on foot, there was no horse in sight, and he must have come

from Pettigrew's Brigade on our left, only some 200 yards distant.

I have written and asked about the command to which this officer belonged,

but have met with no success.

Three times General Pickett sent to Colonel Alexander, asking: "Is it time

to charge?" The last messenger brought back this answer: "Tell General Pickett I think we have silenced eight of the: enemy's

guns, and now is the thee to charge." (Some Federal officers after the war informed me that they had only run these guns back

to cool.)

MOUNTED OFFICERS.

General Pickett ordered his staff-officers, four in number (Major Charles

Pickett, Captain Baird, Captain Symington and myself), to Generals Armistead, Garnett and Kemper, and to Dearing's Artillery

Battalion, which earlier in the day had been ordered to follow up the charge and keep its caissons full. Orders to the other

staff officers I did not hear. But I was sent to General Kemper with this order:

"You and your staff and field officers to go in dismounted; dress on Garnett

and take the red barn for your objective point."

During the charge I found Kemper and Garnett apparently drifting too much

to the left, and I believe it was because the red barn was too much to Kemper's left. General Pickett would have altered the

direction, but our left being exposed by the retreat of Pettigrew's command, our men and 10,000 more were needed to the left.

When I reached General Kemper, he stood up, removing a handkerchief from under

his hat, with which he had covered his face to keep the gravel knocked up by the fierce artillery fire from his eyes. As I

gave the order, Robert McCandlish Jones, a friend and schoolmate of mine, called out: "Bob, turn us loose and we will take

them." Then Colonel Lewis Williams, of the 1st Virginia Regiment, came to me and said: "Captain Bright, I wish to ride my

mare up," and I answered: "Colonel Williams, you cannot do it. Have you not just heard me give the order to your general to

go up on foot?" and he said: "But you will let me ride; I am sick to-day, and besides that, remember Williamsburg." Now Williamsburg

was my home and I remembered that Colonel Williams had been shot through the shoulder in that battle and left at Mrs. Judge

Tucker's house on the courthouse green. This I had heard, for I missed that fight, so I answered: "Mount your mare and I will

make an excuse for you." General Garnett had been injured by a kick while passing through the wagon train at night, had been

allowed to ride; Colonel Hunton of the same brigade also rode, being unable to walk. He fell on one side of the red barn and

General Kemper on the other side.

So there were eight mounted officers, counting General Pickett and staff,

mounted in the charge.

Colonel Williams fell earlier in the fight. His mare went up rideless almost

to the stone wall and was caught when walking back by Captain William C. Marshall, of Dearing's Battalion. His own horse,

Lee, having been killed, he rode Colonel Williams' mare away after the fight. When I returned to General Pickett from giving

the order to General Kemper, Symington, Baird and Charles Pickett were with the General, they having less distance to carry

their orders than I, as Kemper was on our right, and Armistead not in first line, but in echelon.

WHERE PICKETT WAS.

| Pickett's Charge |

|

| Pettigrew-Pickett Charge |

The command had moved about fifty yards in the charge. General Pickett and

staff were about twenty yards in rear of the column.

When we had gone about four hundred yards the General said: "Captain, you

have lost your spurs to-day, instead of gaining them." Riding on the right side, I looked at once at my left boot, and saw

that the shank of my spur had been mashed around and the rowel was looking towards the front, the work of a piece of shell,

I suppose, but that was the first I knew of it. Then I remembered the Irishman's remark, that one spur was enough, because

if one side of your horse went, the other would be sure to go.

When we had charged about 750 yards, having about 500 more to get over before

reaching the stone wall, Pettigrew's Brigade broke all to pieces and left the field in great disorder. At this time we were

mostly under a fierce artillery fire; the heaviest musketry fire came farther on.

General Pettigrew was in command that day of a division and his brigade was

led by Colonel Marshall, who was knocked from his horse by a piece of shell as his men broke, but he had himself lifted on

his horse, and when his men refused to follow him up, he asked that his horse be turned to the front. Then he rode up until.

he was killed. If all the men on Pickett's left had gone on like Marshall, history would have been written another way. General

Pickett sent Captain Symington and Captain Baird to rally these men.

They did all that brave officers could do, but could not stop the stampede.

LONGSTREET AND FREEMANTLE.

General Pickett directed me to ride to General Longstreet and say that the

position against which he had been sent would be taken, but he could not hold it unless reinforcements be sent to him. As

I rode back to General Longstreet I passed small parties of Pettigrew's command going to the rear; presently I came to quite

a large squad, and, very foolishly, for I was burning precious time, I halted them, and asked if they would not go up and

help those gallant men now charging behind us. Then I added, "What are you running for?" and one of them, looking up at me

with much surprise depicted on his face, said. "Why, good gracious, Captain, ain't you running yourself?" Up to the present

time I have not answered that question, but will now say, appearances were against me.

I found General Longstreet sitting on a fence alone; the fence ran in the

direction we were charging. Pickett's column had passed over the hill on our side of the Emmettsburg road, and could not then

be seen. I delivered the message as sent by General Pickett. General Longstreet said: "Where are the troops that were placed

on your flank?" and I answered: "Look over your shoulder and you will see them." He looked and saw the broken fragments. Just

then an officer rode at half-speed, drawing up his horse in front of the General, and saying: "General Longstreet, General

Lee sent me here, and said you would place me in a position to see this magnificent charge. I would not have missed it for

the world." General Longstreet answered: "I would, Colonel Freemantle, the charge is over. Captain Bright, ride to General

Pickett, and tell hin what you have heard me say to Colonel Freemantle." At this moment our men were near to but had not crossed

the Emmettsburg road. I started and when my horse had made two leaps, General Longstreet called: "Captain Bright!" I checked

my horse, and turned half around in my saddle to hear, and this was what he said: "Tell General Pickett that Wilcox's Brigade

is in that peach orchard (pointing), and he can order him to his assistance."

WILCOX AND PICKETT.

Some have claimed that Wilcox was put in the charge at its commencement--General

Gordon says this; but this is a mistake. When I reached General Pickett he was at least one hundred yards behind the division,

having been detained in a position from which he could watch and care for his left flank. He at once sent Captain Baird to

General Wilcox with the order for him to come in; then he sent Captain Symington with the same order, in a very few moments,

and last he said: "Captain Bright, you go,' and I was about the same distance behind Symington that he was behind Baird. The

fire was so dreadful at this time that I believe that General Pickett thought not more than one out of the three sent would

reach General Wilcox.

When I rode up to Wilcox he was standing with both hands raised waving and

saying to me, "I know, I know." I said, "But, General, I must deliver my message." After doing this I rode out of the peach

orchard, going forward where General Pickett was watching his left. Looking that way myself, I saw moving out of the enemy's

line of battle, in head of column, a large force; having nothing in their front, they came around our flank as described above.

Had our left not deserted us these men would have hesitated to move in head of column, confronted by a line of battle. When

I reached General Pickett I found him too far down towards the Ennmettshurg road to see these flanking troops, and he asked

of me the number. I remember answering 7,000, but this proved an over estimate. Some of our men had been faced to meet this

new danger, and so doing somewhat broke the force of our charge on the left. Probably men of the 1st Virginia will remember

this.

ARTILLERY AMMUNITION OUT.

I advised the General to withdraw his command before these troops got down

far enough to left face, come into line of battle, sweep around our flank and shut us up. He said, "I have been watching my

left all the time, expecting this, but it is provided for. Ride to Dearing's Battalion; they have orders to follow up the

charge and keep their caissons filled; order them to open with every gun and break that column and keep it broken." The first

officer I saw on reaching the battalion was Captain William C. Marshall (Post office, Morgantown, West Virginia). I gave him

the order with direction to pass it down at once to the other three batteries. Marshall said: "The battalion has no ammunition.

I have only three solid shot." I then asked why orders to keep caissons filled had not been obeyed, and he answered, "The

caissons had been away nearly three-quarters of an hour, and there was a rumor that General Pendleton had sent the reserve

artillery ammunition more than a mile in rear of the field." I directed him to open with his solid shot, but I knew all hope

of halting the column was over, because solid shot do not halt columns. The second shot struck the head of column, the other

two missed, and the guns were silent.

I found General Pickett in front about 300 yards ahead of the artillery position,

and to the left of it, and some 200 yards behind the command which was then at the stone wall over which some of our men were

going, that is, the 53rd Regiment, part of Armistead's Brigade, led by Colonel Rawley Martin, who fell next to the gallant

General Armistead, had reached the enemy's guns and captured them. All along the stone wall, as far as they extended, Kemper

and Garnett's men were fighting with but few officers left.

THE RETREAT--LEE'S REMARK.

I informed the General that no help was to be expected from the artillery,

but the enemy were closing around us, and nothing could now save his command. He had remained behind to watch and protect

that left, to put in first help expected from infantry supports, then to break the troops which came around his flank with

the artillery; all had failed. At this moment our left (Pickett's Division) began to crumble and soon all that was left came

slowly back, 5,000 in the morning, 1,600 were put in camp that night, 3,400 killed, wounded and missing.

We moved back, and when General Pickett and I were about 300 yards from the

position from which the charge had started, General Robert E. Lee, the Peerless, alone, on Traveler, rode up and said: "General

Pickett, place your division in rear of this hill, and be ready to repel the advance of the enemy should they follow up their

advantage." (I never heard General Lee call them the enemy before; it was always those or these people). General Pickett,

with his head on his breast, said: "General Lee, I have no division now, Armistead is down, Garnett is down, and Kemper is

mortally wounded."

Then General Lee said: "Come, General Pickett, this has been my fight and

upon my shoulders rests the blame. The men and officers of your command have written the name of Virginia as high to-day as

it has ever been written before." (Now talk about "Glory enough for one day," why this was glory enough for one hundred years.)

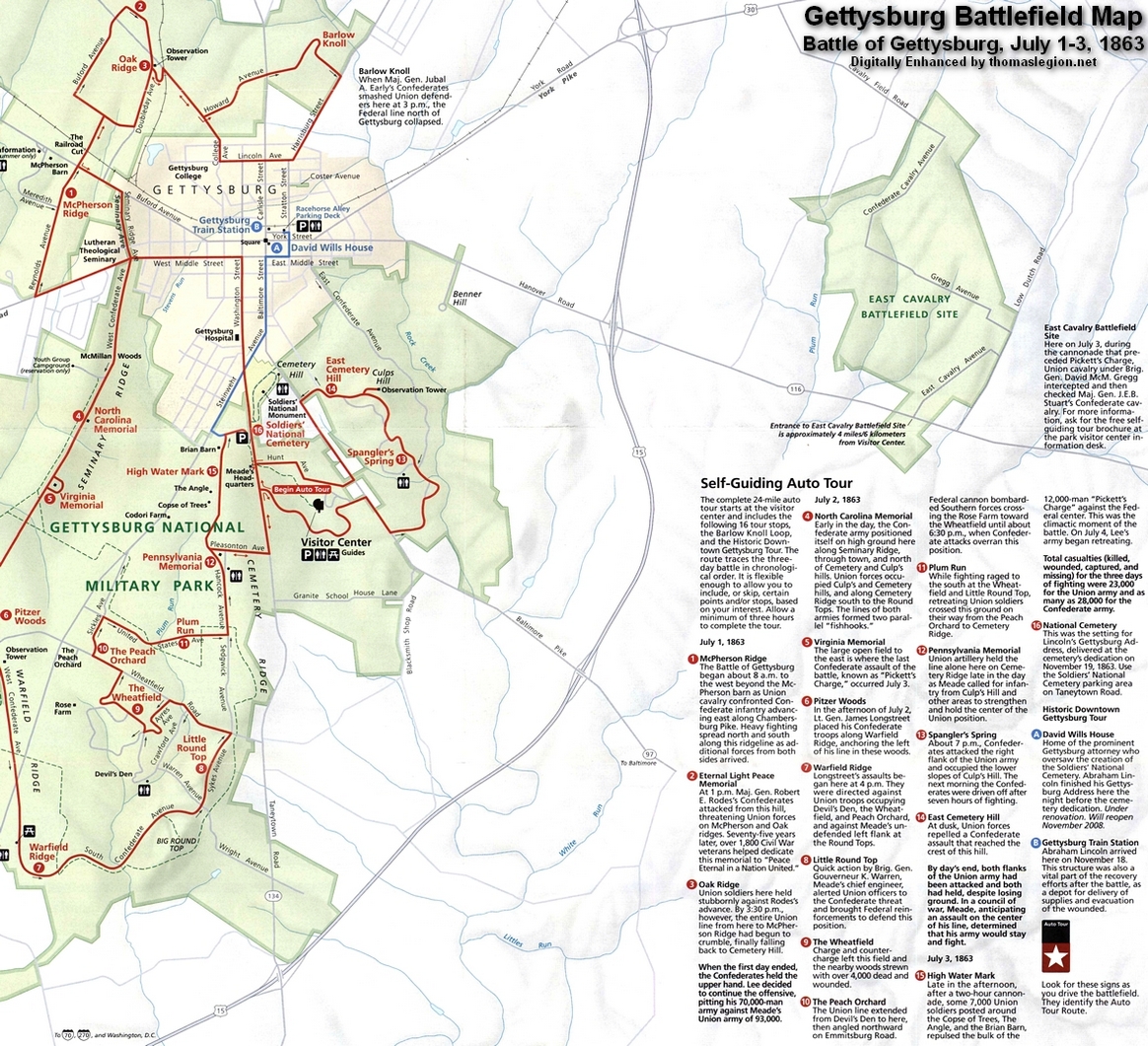

| Pickett's Charge and Battle of Gettysburg Map |

|

| Official Gettysburg Battlefield Map |

LEE AND KEMPER.

Then turning to me, General Lee said: Captain, what officer is that they are

bearing off?" I answered, "General Kemper," and General Lee said: "I must speak to him," and moved Traveler towards the litter.

I moved my horse along with his, but General Pickett did not go with us. The four bearers, seeing it was General Lee, halted,

and General Kemper, feeling the halt, opened his eyes. General Lee said: "General Kemper, I hope you are not very seriously

wounded."

General Kemper answered: "I am struck in the groin, and the ball has ranged

upwards; they tell me it is mortal;" and General Lee said: "I hope it will not prove so bad as that; is there anything I can

do for you, General Kemper?" The answer came, after General Kemper had, seemingly with much pain, raised himself on one elbow:

"Yes, General Lee, do full justice to this division for its work to-day."

General Lee bowed his head, and said: "I will."

I wish to mention here that Captain William I. Clopton, now judge of Manchester,

told me after the war that while General Pickett was trying to guard his left, he saw twenty-seven battleflags, each with

the usual complement of men, move out on our right flank, but we did not see this, as all our thoughts were fixed on our left

flank.

Captain Symington and Captain Baird could each give many interesting incidents

if they could be induced to write for publication. My article of the 10th of December, 1903, in The Times-Dispatch,

should be read before this account, to show how and when General Pickett's command reached Gettysburg.

PERSONAL

Should I write again, it will be about the 4,000 prisoners we guarded back

to Virginia, Kemper's supposed death bed, and General Lee's note to Pickett a few days after Gettysburg. To those seeking

the truth about this great battle, I will say, the very great losses in other commands occurred on the first and second days.

The third day, at this exhibition, was most decidedly Virginia day, and a future Virginia Governor, Kemper by name, was present.

I wish here to state that some of the men of Garnett's Brigade told me they saw up at the stone wall, fighting with them,

some men and officers, mostly the latter, of two other States, and in answer to my questions as to numbers and organization,

answered, numbering in all, less than sixty, and without formation of any military kind, Alabamians and North Carolinians.

Now, as to the position of Armistead's Brigade in the charge. He was ordered

to go in on the left of Garnett, but Captain Winfree, a most gallant officer of the 14th Virginia, now living in

this city, agrees with my memory, that Armistead's brigade went in between Garnett and Kemper. I also wish to give such information

as I can to Senator Daniel, who asked for it in the Confederate column of Sunday's Times-Dispatch, 24th

of January, about the losses of Pickett's three brigades on the third day. No official returns came to us until long after

the battle, because no one was left to make the report, and hardly any one was left to receive such report. General Pickett's

staff officers who encamped the command on the night of the third day counted sixteen hundred. I find Senator Daniel since

the war always turning from Washington to Virginia, like the needle to the pole, but, strange to say, during the war I found

him always turning from Virginia to Washington as though he wanted that city.

Very respectfully, Ro. A. BRIGHT,

Formerly on the staff of Major-General George E. Pickett.

(Source: Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 31, pp. 228-236)

Recommended Reading: Pickett's Charge,

by George Stewart. Description: The author has written

an eminently readable, thoroughly enjoyable, and well-researched book on the third day of the Gettysburg battle, July 3, 1863. An especially rewarding read if one has toured, or plans

to visit, the battlefield site. The author's unpretentious, conversational style of writing succeeds in putting the reader

on the ground occupied by both the Confederate and Union forces before, during and after

Pickett's and Pettigrew's famous assault on Meade's Second Corps. Continued below...

Interspersed

with humor and down-to-earth observations concerning battlefield conditions, the author conscientiously describes all aspects

of the battle, from massing of the assault columns and pre-assault artillery barrage to the last shots and the flight of the

surviving rebels back to the safety of their lines… Having visited Gettysburg several years ago, this superb volume makes me

want to go again.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's Charge--The Last Attack at Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: Pickett's Charge is probably the best-known military engagement of the Civil War, widely

regarded as the defining moment of the battle of Gettysburg

and celebrated as the high-water mark of the Confederacy. But as Earl Hess notes, the epic stature of Pickett's Charge has

grown at the expense of reality, and the facts of the attack have been obscured or distorted by the legend that surrounds

them. With this book, Hess sweeps away the accumulated myths about Pickett's Charge to provide the definitive history of the

engagement. Continued below...

Drawing on

exhaustive research, especially in unpublished personal accounts, he creates a moving narrative of the attack from both Union and Confederate

perspectives, analyzing its planning, execution, aftermath, and legacy. He also examines the history of the units involved,

their state of readiness, how they maneuvered under fire, and what the men who marched in the ranks thought about their participation

in the assault. Ultimately, Hess explains, such an approach reveals Pickett's Charge both as a case study in how soldiers

deal with combat and as a dramatic example of heroism, failure, and fate on the battlefield.

Recommended Reading:

Pickett's Charge in History and Memory. Description: Pickett's Charge--the Confederates' desperate (and failed) attempt to break the Union

lines on the third and final day of the Battle of Gettysburg--is best remembered as the turning point of the U.S. Civil War.

But Penn State

historian Carol Reardon reveals how hard it is to remember the past accurately, especially when an event such as this one

so quickly slipped into myth. Continued below...

She writes,

"From the time the battle smoke cleared, Pickett's Charge took on this chameleon-like aspect and, through a variety of carefully

constructed nuances, adjusted superbly to satisfy the changing needs of Northerners, Southerners, and, finally, the entire

nation." With care and detail, Reardon's

fascinating book teaches a lesson in the uses and misuses of history.

Recommended Reading: Last Chance For Victory: Robert E. Lee And

The Gettysburg Campaign. Description: Long after

nearly fifty thousand soldiers shed their blood there, serious misunderstandings persist about Robert E. Lee's generalship

at Gettysburg. What were Lee's choices before, during, and

after the battle? What did he know that caused him to act as he did? Last Chance for Victory addresses these issues by studying

Lee's decisions and the military intelligence he possessed when each was made. Continued below...

Packed with

new information and original research, Last Chance for Victory draws alarming conclusions to complex issues with precision

and clarity. Readers will never look at Robert E. Lee and Gettysburg the same way again.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's

Charge: Eyewitness Accounts At The Battle Of Gettysburg

(Stackpole Military History Series). Description: On

the final day of the battle of Gettysburg, Robert E. Lee ordered

one of the most famous infantry assaults of all time: Pickett's Charge. Following a thundering artillery barrage, thousands

of Confederates launched a daring frontal attack on the Union line. From their entrenched positions, Federal soldiers decimated

the charging Rebels, leaving the field littered with the fallen and several Southern divisions in tatters. Written by generals,

officers, and enlisted men on both sides, these firsthand accounts offer an up-close look at Civil War combat and a panoramic

view of the carnage of July 3, 1863.

|