|

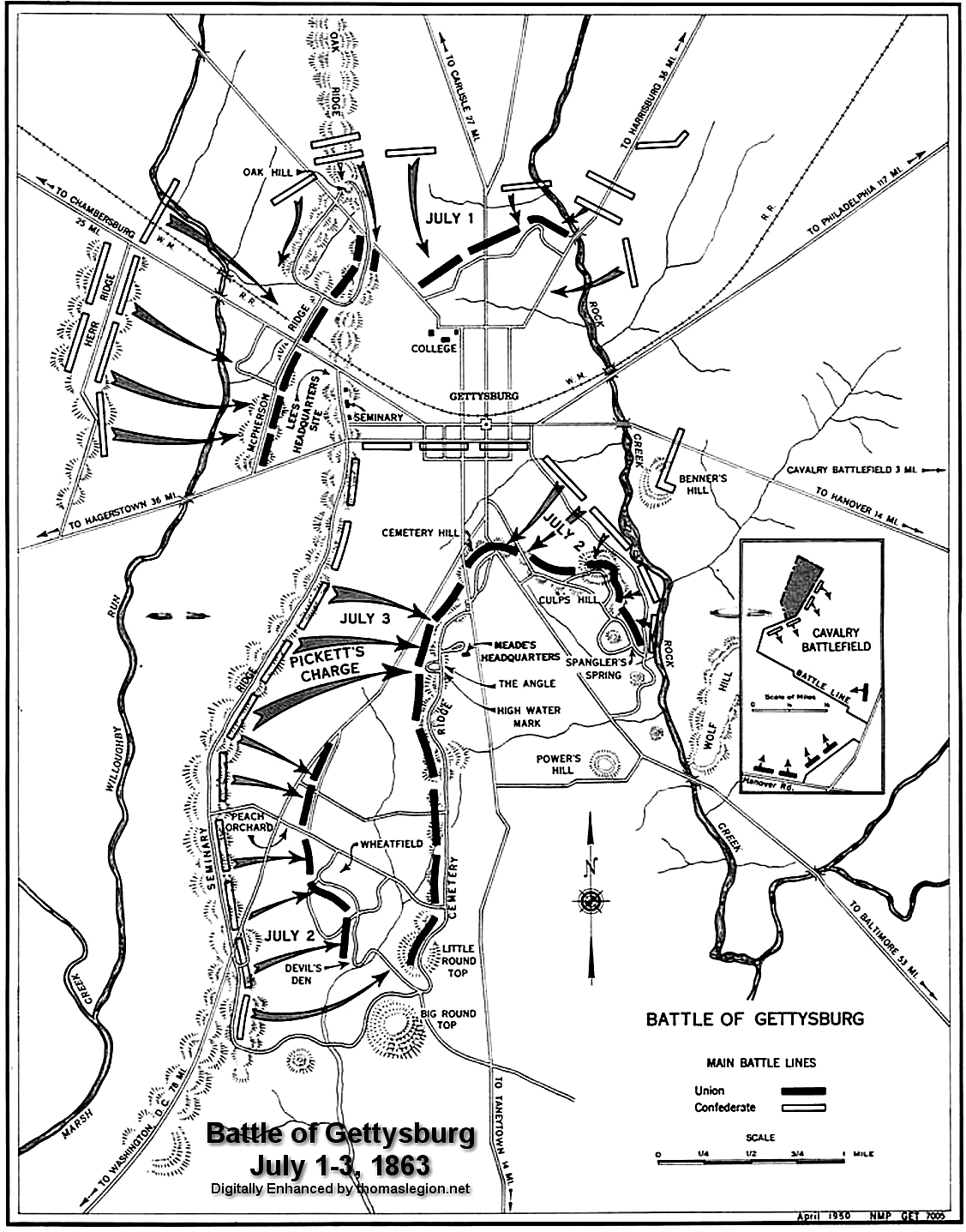

BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG AND PICKETT'S CHARGE

[From the Times-Dispatch, April 10, 1904.]

THE BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG,

And the Charge

of Pickett's Division.

ACCOUNTS OF COLONEL RAWLEY MARTIN AND CAPTAIN

JOHN HOLMES SMITH.

With Prefatory Note by U. S. Senator John W. Daniel.

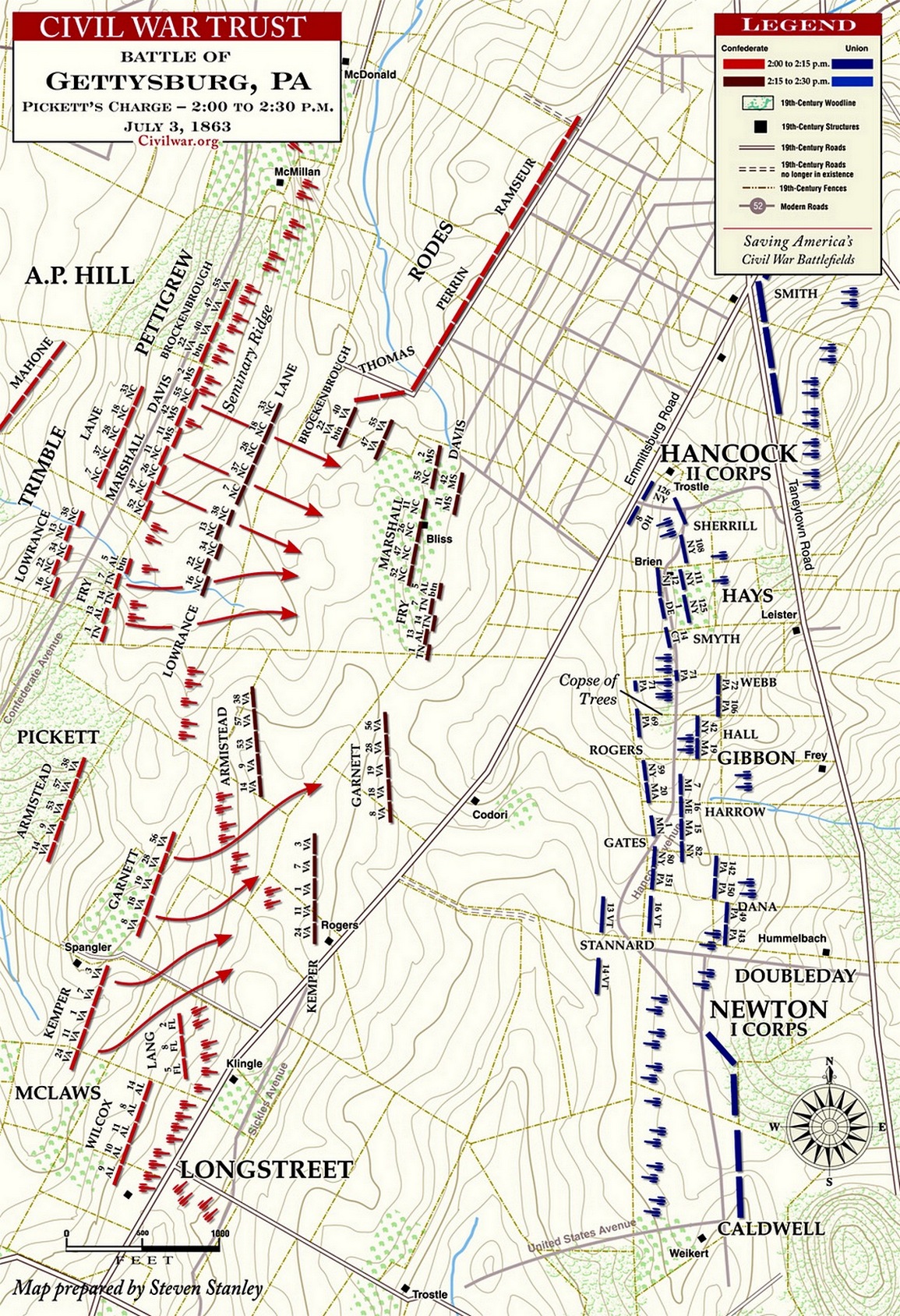

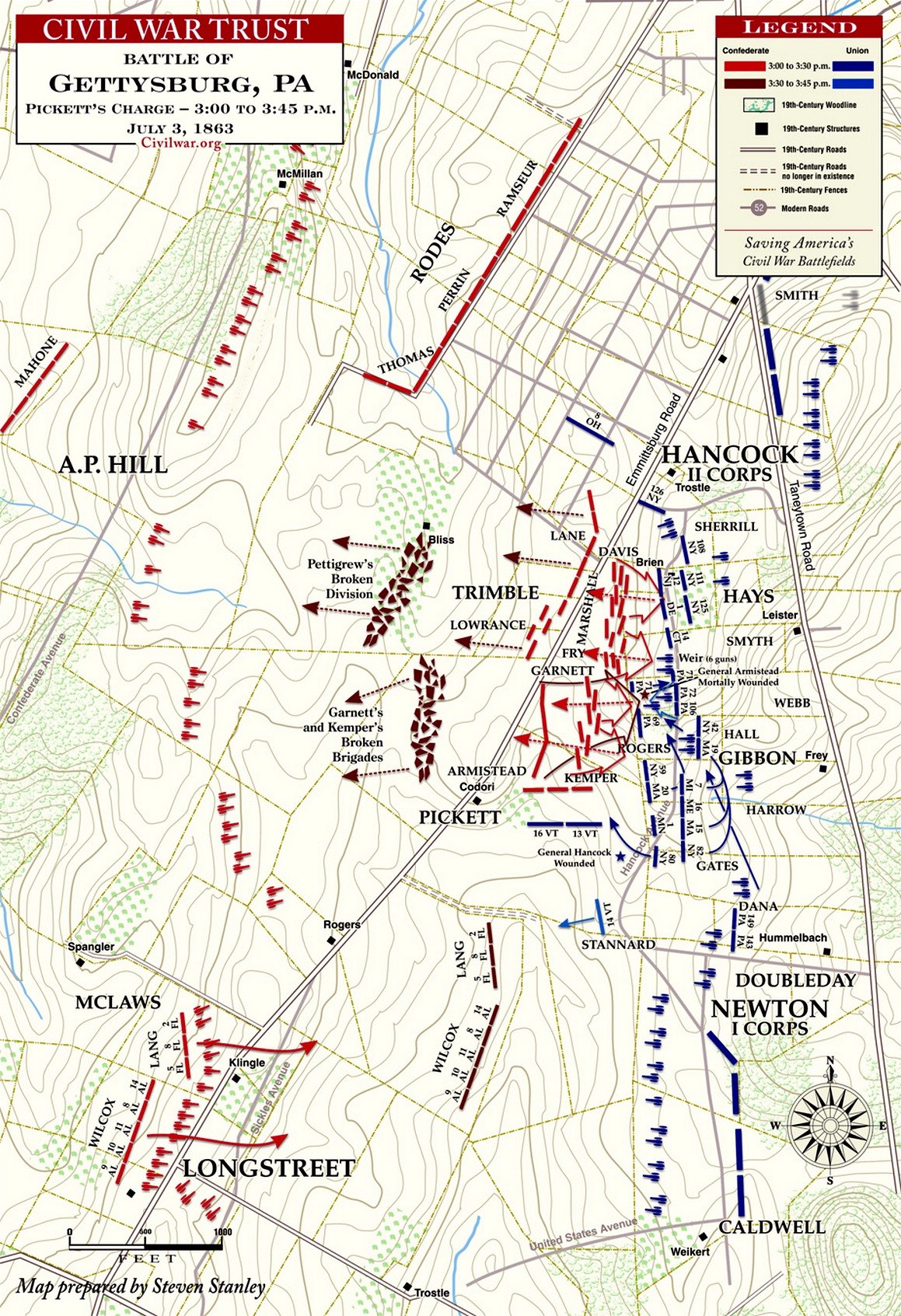

| Pickett's Charge |

|

| Pettigrew-Pickett Charge, more popularly known as Pickett's Charge |

[Very much has been published regarding the momentous battle of

Gettysburg, but the following additions can but be welcome to our readers. Reference may be made to ante p. 33 and

preceeding volumes of the Southern Historical Society Papers, particularly the early volumes, II-X inclusive.--Editor.]

Washington, D. C., March 30, 1904

Editor of The Times-Dispatch:

Sir,--Enclosed are accounts of the charge at Gettysburg by two officers of

Pickett's Division of high reputation for courage an reliability--the one being Lieutenant-Colonel Rawley W. Martin, then

of the 53d Virginia Infantry, Armistead's Brigade, and the other Captain John Holmes Smith, of the Lynchburg Home Guard, who,

after Lieutenant-Colonel Kirkwood Otey, and Major Risque Hutter, were wounded in that battle, commanded the 11th Virginia

Infantry.

In 1897 Commander Sylvester Chamberlain, of an Association of United States

Naval Veterans, of Buffalo, New York, wrote to Colonel Martin (now Dr. Martin, of Lynchburg, Va.), asking him to recount the

charge, saying:

"The charge of Pickett's Division outrivals the storied heroism of the Old

Guard of Napoleon. They knew no such battle as that of Gettysburg, and, I believe, the old First Confederate Army Corps could

have whipped the best two corps in Napoleon's army, taken in the zenith of his fame."

Dr. Martin wrote this paper under the call from a Northern camp commander.

Captain John Holmes Smith was with his regiment on the right wing of Pickett's

charge, under Kemper, and struck the Federal line to the right of where General Armistead made the break. The soldiers of

Kemper there took the Federal entrenchments, and remained about twenty minutes in possession of them. Twice couriers were

sent back for reinforcements. Slowly, but surely, the details of this magnificent exploit of war come to light; and the more

brilliant does it appear. Slowly, and surely, also do the evidences gather that point toward the responsible agents of the

failure that ensued.

Respectfully,

Jno. W. Daniel.

COLONEL RAWLEY MARTIN'S ACCOUNT.

Lynchburg Va., August 11, 1897.

Commander Sylvester Chamberlain, Buffalo, N. Y.:

My dear Sir,--In the effort to comply with your request to

describe Pickett's charge at Gettysburg, I may unavoidably repeat what has often been told before, as the position of troops,

the cannonade, the advance, and the final disaster are familiar to all who have the interest or the curiosity to read. My

story will be short, for I shall only attempt to describe what fell under my own observation.

You ask for a description of the "feelings of the brave Virginians who passed

through that hell of fire in their heroic charge on Cemetery Ridge." The esprit du corps could not have been better;

the men were in good physical condition, self reliant and determined. They felt the gravity of the situation, for they knew

well the metal of the foe in their front; they were serious and resolute, but not disheartened. None of the usual jokes, common

on the eve of battle, were indulged in, for every man felt his individual responsibility, and realized that he had the most

stupendous work of his life before him; officers and men knew at what cost and at what risk the advance was to be made, but

they had deliberately made up their minds to attempt it. I believe the general sentiment of the division was that they would

succeed in driving the Federal line from what was their objective point; they knew that many, very many, would go down under

the storm of shot and shell which would greet them when their gray ranks were spread out to view, but it never occurred to

them that disaster would come after they once placed their tattered banners upon the crest of Seminary Ridge.

THEIR NERVE.

I believe if those men had been told: "This day your lives will pay the penalty

of your attack upon the Federal lines," they would have made the charge just as it was made. There was no straggling, no feigned

sickness, no pretense of being overcome by the intense heat; every man felt that it was his duty to make that fight; that

he was his own commander, and they would have made the charge without an officer of any description; they only needed to be

told what they were expected to do. This is as near the feeling of the men of Pickett's Division on the morning of the battle

as I can give, and with this feeling they went to their work. Many of them were veteran soldiers, who had followed the little

cross of stars from Big Bethel to Gettysburg; they knew their own power, and they knew the temper of their adversary; they

had often met before, and they knew the meeting before them would be desperate and deadly.

| Pickett's Charge |

|

| Pickett's Charge, Battle of Gettysburg, July 3, 1863 |

| Pickett's Charge at Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| Repulse of Pickett's Charge |

THE ALIGNMENT.

Pickett's three little Virginia brigades were drawn up in two lines, Kemper

on the right (1st, 3d, 7th, 11th and 24), Garnett on the left (8th, 18th, 19th, 28th and 56th), and Armistead in the rear

and center (9th, 14th, 38th, 53d and 57th) Virginia Regiments, covering the space between Kemper's left and Garnett's right

flanks. This position was assigned Armistead, I suppose, that he might at the critical moment rush to the assistance of the

two leading brigades, and if possible, put the capstone upon their work. We will see presently how he succeeded. The Confederate

artillery was on the crest of Seminary Ridge, nearly in front of Pickett; only a part of the division had the friendly shelter

of the woods; the rest endured the scorching rays of the July sun until the opening of the cannonade, when the dangers from

the Federal batteries were added to their discomfort. About 1 o'clock two signal guns were fired by the Washington Artillery,

and instantly a terrific cannonade was commenced, which lasted for more than an hour, when suddenly everything was silent.

Every man knew what that silence portended. The grim blue battle line on Seminary Ridge began at once to prepare for the advance

of its antagonists; both sides felt that the tug of war was about to come, and that Greek must meet Greek as they had never

met before.

A SOLEMN MOMENT.

From this point, I shall confine my description to events connected with Armistead's

brigade, with which I served. Soon after the cannonade ceased, a courier dashed up to General Armistead, who was pacing up

and down in front of the 53d Virginia Regiment, his battalion of direction (which I commanded in the charge and at the head

of which Armistead marched), and gave him the order from General Pickett to prepare for the advance. At once the command "Attention,

battalion!" rang out clear and distinct. Instantly every man was on his feet and in his place; the alignment was made with

as much coolness and precision as if preparing for dress parade. Then Armistead went up to the color sergeant of the 53d Virginia

Regiment and said: "Sergeant, are you going to put those colors on the enemy's works to-day?" The gallant fellow replied:

"I will try, sir, and if mortal man can do it, it shall be done." It was done, but not until this brave man, and many others

like him, had fallen with their faces to the foe; bur never once did that banner trail in the dust, for some brave fellow

invariably caught it as it was going down, and again bore it aloft, until Armistead saw its tattered folds unfurled on the

very crest of Seminary Ridge.

THE ADVANCE.

After this exchange of confidence between the general and the color-bearer,

Armistead commanded: "Right shoulder, shift arms. Forward, march." They stepped out at quick time, in perfect order and alignment--tramp,

tramp, up to the Emmittsburg road; then the advancing Confederates saw the long line of blue, nearly a mile distant, ready

and awaiting their coming. The scene was grand and terrible, and well calculated to demoralize the stoutest heart; but not

a step faltered, not an elbow lost the touch of its neighbor, not a face blanched, for these men had determined to do their

whole duty, and reckoned not the cost. On they go; at about 1,100 yards the Federal batteries opened fire; the advancing Confederates

encounter and sweep before them the Federal skirmish line. Still forward they go; hissing, screaming shells break in their

front, rear, on their flanks, all about them, but the devoted band, with the blue line in their front as their objective point,

press forward, keeping step to the music of the battle. The distance between the opposing forces grows less and less, until

suddenly the infantry behind the rock fence poured volley after volley into the advancing ranks. The men fell like stalks

of grain before the reaper, but still they closed the gaps and pressed forward through that pitiless storm. The two advance

brigades have thus far done the fighting. Armistead has endured the terrible ordeal without firing a gun; his brave followers

have not changed their guns from the right shoulder. Great gaps have been torn in their ranks; their field and company officers

have fallen; color-bearer after color-bearer has been shot down, but still they never faltered.

THE CRITICAL MOMENT.

At the critical moment, in response to a request from Kemper, Armistead, bracing

himself to the desperate blow, rushed forward to Kemper's and Garnett's line, delivered his fire, and with one supreme effort

planted his colors on the famous rock fence. Armistead himself, with his hat on the point of his sword, that his men might

see it through the smoke of battle, rushed forward, scaled the wall, and cried: "Boys, give them the cold steel!" By this

time, the Federal hosts lapped around both flanks and made a counter advance in their front, and the remnant of those three

little brigades melted away. Armistead himself had fallen, mortally wounded, under the guns he had captured, while the few

who followed him over the fence were either dead or wounded. The charge was over, the sacrifice had been made, but, in the

words of a Federal officer: "Banks of heroes they were; they fled not, but amidst that still continuous and terrible fire

they slowly, sullenly recrossed the plain--all that was left of them--but few of the five thousand."

WHERE WAS PICKETT.

When the advance commenced General Pickett rode up and down in rear of Kemper

and Garnett, and in this position he continued as long as there was opportunity of observing him. When the assault became

so fierce that he had to superintend the whole line, I am sure he was in his proper place. A few years ago Pickett's staff

held a meeting in the city of Richmond, Va., and after comparing recollections, they published a statement to the effect that

he was with the division throughout the charge; that he made an effort to secure reinforcements when he saw his flanks were

being turned, and one of General Garnett's couriers testified that he carried orders from him almost to the rock fence. From

my knowledge of General Pickett I am sure he was where his duty called him throughout the engagement. He was too fine a soldier,

and had fought too many battles not to be where he was most needed on that supreme occasion of his military life.

The ground over which the charge was made was an open terrene, with slight

depressions and elevations, but insufficient to be serviceable to the advancing column. At the Emmettsburg road, where the

parallel fences impeded the onward march, large numbers were shot down on account of the crowding at the openings where the

fences had been thrown down, and on account of the halt in order to climb the fences. After passing these obstacles, the advancing

column deliberately rearranged its lines and moved forward. Great gaps were made in their ranks as they moved on, but they

were closed up as deliberately and promptly as if on the parade ground; the touch of elbows was always to the centre, the

men keeping constantly in view the little emblem which was their beacon light to guide them to glory and to death.

INSTANCES OF COURAGE.

I will mention a few instances of individual coolness and bravery exhibited

in the charge. In the 53d Virginia Regiment, I saw every man of Company F (Captain Henry Edmunds, now a distinguished member

of the Virginia bar) thrown flat to the earth by the explosion of a shell from Round Top, but every man who was not killed

or desperately wounded sprang to his feet, collected himself and moved forward to close the gap made in the regimental front.

A soldier from the same regiment was shot on the shin; he stopped in the midst of that terrific fire, rolled up his trousers

leg, examined his wound, and went forward even to the rock fence. He escaped further injury, and was one of the few who returned

to his friends, but so bad was his wound that it was nearly a year before he was fit for duty. When Kemper was riding off,

after asking Armistead to move up to his support, Armistead called him, and, pointing to his brigade, said: "Did you ever

see a more perfect line than that on dress parade?" It was, indeed, a lance head of steel, whose metal had been tempered in

the furnace of conflict. As they were about to enter upon their work, Armistead, as was invariably his custom on going into

battle, said: "Men, remember your wives, your mothers, your sisters and you sweethearts." Such an appeal would have made those

men assault the ramparts of the infernal regions.

| Pickett's Charge and Battle of Gettysburg |

|

| The Three Day Battle of Gettysburg |

AFTER THE CHARGE.

You asked me to tell how the field looked after the charge, and how the men

went back. This I am unable to do, as I was disabled at Armistead's side a moment after he had fallen, and left on the Federal

side of the stone fence. I was picked up by the Union forces after their lines were reformed, and I take this occasion to

express my grateful recollection of the attention I received on the field, particularly from Colonel Hess, of the 72d Pennsylvania

(I think). If he still lives, I hope yet to have the pleasure of grasping his hand and expressing to him my gratitude for

his kindness to me. Only the brave know how to treat a fallen foe.

I cannot close this letter without reference to the Confederate chief, General

R. E. Lee. Somebody blundered at Gettysburg but not Lee. He was too great a master of the art of war to have hurled a handful

of men against an army. It has been abundantly shown that the fault lay not with him, but with others, who failed to execute

his orders.

This has been written amid interruptions, and is an imperfect attempt to describe

the great charge, but I have made the effort to comply with your request because of your very kind and friendly letter, and

because there is no reason why those who once were foes should not now be friends. The quarrel was not personal, but sectional,

and although we tried to destroy each other thirty-odd years ago, there is no reason why we should cherish resentment against

each other now.

I should be very glad to meet you in Lynchburg if your business or pleasure

should ever bring you to Virginia.

With great respect,

Yours most truly,

Rawley W. Martin.

__________

CAPTAIN JOHN HOLMES SMITH'S ACCOUNT.

Lynchburg, Va., Feb. 4th and 5th.

John Holmes Smith, formerly Captain of Company G (the Home Guard), of Lynchburg,

Va., and part of the 11th Virginia Infantry, Kemper's Brigade, Pickett's Division, 1st Corps (Longstreet), C. S. A., commanded

that company, and then the regiment for a time in the battle of Gettysburg. He says as follows, concerning that battle:

The 11th Virginia Infantry arrived near Gettysburg, marching from Chambersburg

on the afternoon of July 2d, 1863. We halted in sight of shells bursting in the front.

Very early on the morning of the 3d July we formed in rear of the Confederate

artillery near Spurgeon's woods, where we lay for many hours. I noticed on the early morning as we were taking positions the

long shadows cast by the figures of the men, their legs appearing to lengthen immediately as the shadows fell.

The 11th Virginia was the right regiment of Kemper's Brigade and of Pickett's

Division. No notable event occurred in the morning, nor was there any firing of note near us that specially attracted my attention.

SIGNAL GUNS.

About 1 o'clock there was the fire of signal guns, and there were outbursts

of artillery on both sides. Our artillery on the immediate front of the regiment was on the crest of the ridge, and our infantry

line was from one to 250 yards in rear of it.

We suffered considerable loss before we moved. I had twenty-nine men in my

company for duty that morning. Edward Valentine and two Jennings brothers (William Jennings) of my company were killed; De

Witt Guy, sergeant, was wounded, and some of the men--a man now and a man then--were also struck and sent to the rear before

we moved forward--I think about ten killed and wounded in that position. Company E, on my right, lost more seriously than

Company G, and was larger in number.

LONGSTREET'S PRESENCE.

Just before the artillery fire ceased General Longstreet rode in a walk between

the artillery and the infantry, in front of the regiment toward the left and disappeared down the line. He was as quiet as

an old farmer riding over his plantation on a Sunday morning, and looked neither to the right or left.

It had been known for hours that we were to assail the enemy's lines in front.

We fully expected to take them.

Presently the artillery ceased firing. Attention! was the command. Our skirmishers

were thrown to the front, and "forward, quick time, march," was the word given. We were ordered not to fire until so commanded.

Lieutenant-Colonel Kirkwood Otey was thus in command of the regiment when we passed over the crest of the ridge, through our

guns there planted, and had advanced some distance down the slope in our front. I was surprised before that our skirmishers

had been brought to a stand by those of the enemy; and the latter only gave ground when our line of battle had closed up well

inside of a hundred yards of our own skirmishers. The enemy's skirmishers then retreated in perfect order, firing as they

fell back.

The enemy's artillery, front and flank, fired upon us, and many of the regiment

were struck.

UP THE HILL.

Having descended the slope and commenced to ascend the opposite slope that

rises toward the enemy's works, the Federal skirmishers kept up their fire until we were some four hundred yards from the

works. They thus being between two fires--for infantry fire broke out from the works--threw down their arms, rushed into our

lines, and then sought refuge in the depression, waterway or gully between the slopes.

There was no distinct change of front; but "close and dress to the left" was

the command, and this gave us an oblique movement to the left as we pressed ranks in that direction.

Our colors were knocked down several times as we descended the slope on our

side. Twice I saw the color-bearer stagger and the next man seize the staff and go ahead; the third time the colors struck

the ground as we were still on the down slope. The artillery had opened upon us with canister. H. V. Harris, adjutant of the

regiment, rushed to them and seized them, and, I think, carried them to the enemy's works.

AT THE WORKS.

When the enemy's infantry opened fire on us--and we were several hundred yards

distant from them as yet--we rushed towards the works, running, I may say, almost at top speed, and as we neared the works

I could see a good line of battle, thick and substantial, firing upon us. When inside of a hundred yards of them I could see,

first, a few, and then more and more, and presently, to my surprise and disgust, the whole line break away in flight. When

we got to the works, which were a hasty trench and embankment, and not a stone wall at the point we struck, our regiment was

a mass or ball, all mixed together, without company organization. Some of the 24th and 3d seemed to be coming with us, and

it may be others. Not a man could I see in the enemy's works, but on account of the small timber and the lay of the ground,

I could not see very far along the line, either right or left, of the position we occupied.

There were, as I thought at the time I viewed the situation, about three hundred

men in the party with me, or maybe less. Adjutant H. V. Harris, of the regimental staff, was there dismounted. Captain Fry,

Assistant Adjutant-General of General Kemper, was also there on foot, with a courier, who was a long-legged, big-footed fellow,

whom we called "Big Foot Walker," also afoot. Captain R. W. Douthat, of Company F, I also noticed, and there were some other

regimental officers whom I cannot now recall.

BIG FOOT WALKER.

We thought our work was done, and that the day was over, for the last enemy

in sight we had seen disappear over the hill in front; and I expected to see General Lee's army marching up to take possession

of the field. As I looked over the work of our advance with this expectation, I could see nothing but dead and wounded men

and horses in the field beyond us, and my heart never in my life sank as it did then. It was a grievous disappointment.

Instantly men turned to each other with anxious inquiries what to do, and

a number of officers grouped together in consultation, Captain Fry, Captain Douthat, Adjutant Harris, and myself, who are

above noted, amongst them. No field officer appeared at this point that I could discover. We promptly decided to send a courier

for reinforcements. No mounted man was there. "Big Foot Walker" was dispatched on that errand. Fearing some mishap to him,

for shots from the artillery on our right, from the enemy's left, were still sweeping the field, we in a few moments sent

another courier for reinforcements.

We were so anxious to maintain the position we had gained, that we watched

the two men we had sent to our rear across the field, and saw them both, the one after the other, disappear over the ridge

from which we had marched forward.

WAIT FOR TWENTY MINUTES.

Unmolested from the front or on either side, and with nothing to indicate

that we would be assailed, we thus remained for fully twenty minutes after Walker had been sent for reinforcements--waited

long after he had disappeared on his mission over the ridge in our rear.

Seeing no sign of coming help, anticipating that we would soon be attacked,

and being in no condition of numbers or power to resist any serious assault, we soon concluded--that is, the officers above

referred to--to send the men back to our lines, and we so ordered.

Lest they might attract the fire of the guns that still kept up a cannonade

from the enemy's left, we told the men to scatter as they retired, and they did fall back singly and in small groups, the

officers before named retiring also. Only Captain Ro. W. Douthat and myself remained at the works, while the rest of the party

we were with, retired. I remained to dress a wound on my right leg, which was bleeding freely, and Douthat, I suppose, just

to be with me. I dropped to the ground under the shade of the timber after the men left, pulled out a towel from my haversack,

cut it into strips, and bandaged my thigh, through which a bullet had passed.

This wound had been received as we approached the enemy's skirmishers on the

descending slope, one of them having shot me. I thought at the time I was knocked out, but did not fall, and I said to James

R. Kent, sergeant: "Take charge of the company, I am shot." But soon finding I could move my leg and that I could go on, no

bones being broken, I went to the end of the charge.

GETTING AWAY.

While I was still bandaging my leg at the works, my companion, Captain Robert

W. Douthat, who had picked up a musket, commenced firing and fired several shots. Thinking he had spied an enemy in the distance,

I continued bandaging my leg, and completed the operation.

When raising myself on my elbow I saw the head of a column of Federal troops

about seventy-five yards toward our right front, advancing obliquely toward us. I was horrified, jumped up and exclaimed to

Douthat: "What are you doing?" as he faced in their direction. He dropped his gun and answered: "It's time to get away from

here," and I started on the run behind him, as we both rapidly retired from the advancing foes. We made good time getting

away, and got some distance before they opened fire on us--perhaps 100 or 150 yards. We ran out of range, shot after shot

falling around us, until we got over the Emmettsburg road toward our lines. After we had got over the fences along the road

the fire didn't disturb us. No organized body of troops did I meet in going back. I wondered how few I saw in this retreat

from the hill top. I reached ere long the tent of a friend, Captain Charles M. Blackford, judge advocate of our Second Corps,

at Longstreet's headquarters, and this was the last of the battle of Gettysburg time. I didn't hear of Lieutenant-Colonel

Otey being wounded until after the battle was over, though I have since understood it was shortly after the advance commenced.

I, the Captain of Company G, was the only commissioned officer with the company that day. I may properly mention an incident

or two.

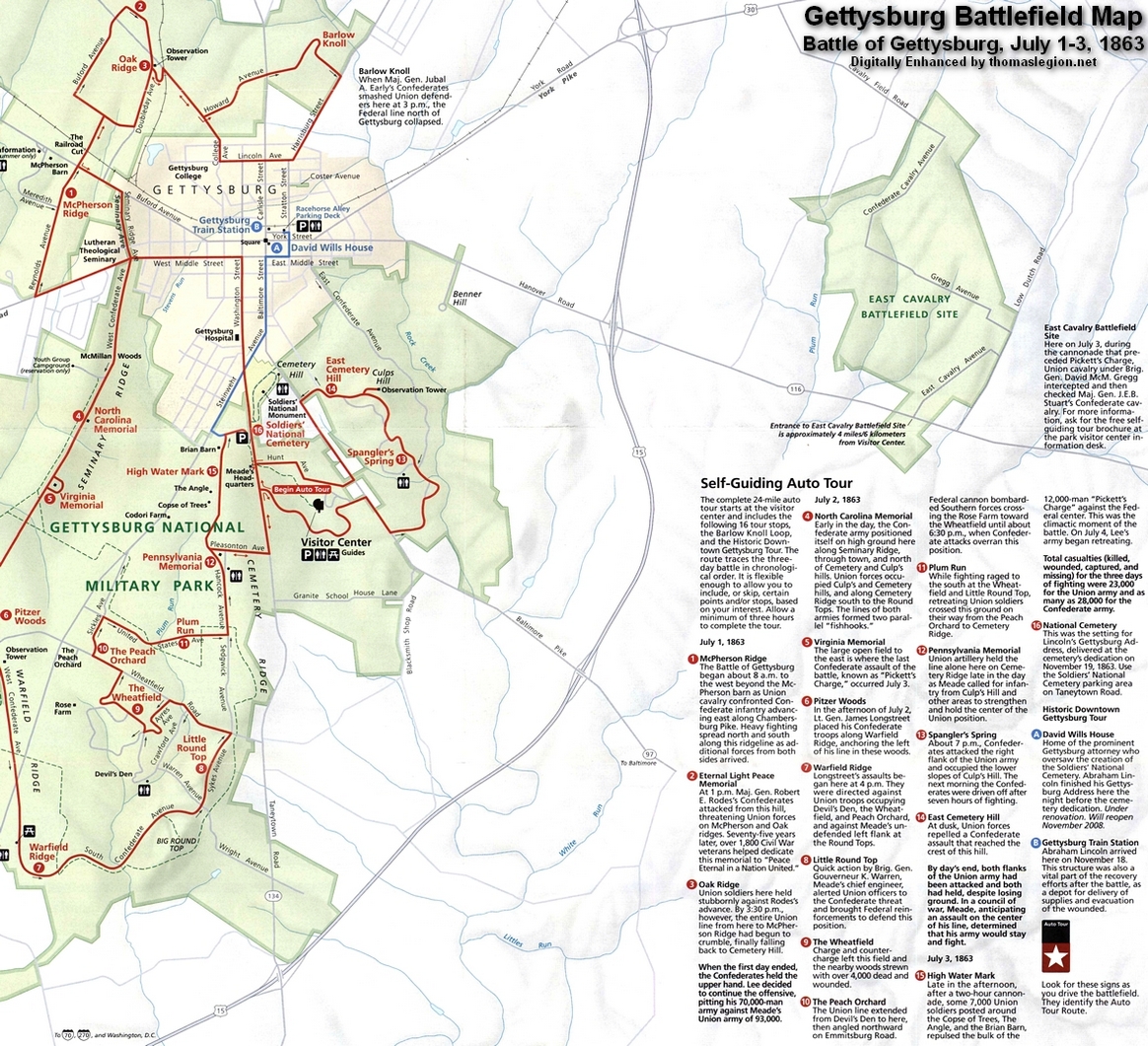

| Pickett's Charge Map |

|

| Official Gettysburg Battlefield Map |

WOUNDED.

Now the battery of the descending slope was advanced. Sergeant James R. Kent,

of my company, suddenly plunged forward in a ditch, and I asked of him: "How are you hurt, Kent?" for I knew he was hit. He

answered: "Shot through the leg." About the time we sent "Big Foot Walker" back for reinforcements, "Blackeyed Williams,"

as we called him, a private of my company, called to me: "Look here, Captain," at the same time pulling up his shirt at the

back and showing a cut where a bullet had a full mark about its depth in the flesh. Quite a number of the men on the hill

top had been struck one way or another, and there were many nursing and tying up their wounds. Kent's leg had been fractured--the

small bone--and he was captured.

Before an advance I went several times to the crest where our artillery was

planted, and could see the enemy in our front throwing up dirt on the line which we afterwards took. Just before the cannonade

commenced Major James Downing rode along the line of guns in our immediate front, carrying a flag.

PERSONAL.

I came away from Longstreet's headquarters after spending the night (after

the battle in Captain Blackford's tent) in a wagon with a long train of wagons that carried one to Williamsport, leaving about

noon and traveling through the next night. Next morning we reached Williamsport. The town was attacked at several points,

but not where I was.

Captain William Early--or Lieutenant Early, as he was then--I met at Williamsport

as I got out of the wagons, and asked me to dinner. I told him I couldn't walk, for I was sore and stiff, and he went off

to get me a horse. But he didn't return, and I did not see him again, for just then his guns opened and a lively skirmish

ensued, but soon quieted down. After remaining a few hours on the north side of the river, a big ferry boat was brought up,

and, having collected fifty or sixty of the 11th Virginia infantry who were wounded, I took charge of them and carried them

on the boat across the river that evening. Then we marched next morning for Winchester, reaching there in two days. I did

not see my regiment in the campaign after the fight. In a few months my leg healed and I rejoined my regiment at Hanover junction

in the fall.

The above is correct.

Jno. Holmes Smith,

Late Captain Company G, Home Guards,

of Lynchburg, Va.

(Source: Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 32, pp. 183-195)

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg,

by Stephen W. Sears (640 pages) (November 3, 2004). Description: Sears delivers another masterpiece with this comprehensive study of America’s most studied Civil War battle. Beginning with Lee's meeting with

Davis in May 1863, where he argued in favor of marching north, to take pressure off both Vicksburg and Confederate logistics. It ends with the battered Army

of Northern Virginia re-crossing the Potomac just two months later and with Meade unwilling to drive his equally battered

Army of the Potomac into a desperate pursuit. In between is the balanced, clear and detailed

story of how tens-of-thousands of men became casualties, and how Confederate independence on that battlefield was put forever

out of reach. The author is fair and balanced. Continued below...

He discusses

the shortcomings of Dan Sickles, who advanced against orders on the second day; Oliver Howard, whose Corps broke and was routed

on the first day; and Richard Ewell, who decided not to take Culp's Hill on the first night, when that might have been decisive.

Sears also makes a strong argument that Lee was not fully in control of his army on the march or in the battle, a view conceived

in his gripping narrative of Pickett's Charge, which makes many aspects of that nightmare much clearer than previous studies.

A must have for the Civil War buff and anyone remotely interested in American history.

Recommended Reading: Pickett's Charge,

by George Stewart. Description: The author has written

an eminently readable, thoroughly enjoyable, and well-researched book on the third day of the Gettysburg battle, July 3, 1863. An especially rewarding read if one has toured, or plans

to visit, the battlefield site. The author's unpretentious, conversational style of writing succeeds in putting the reader

on the ground occupied by both the Confederate and Union forces before, during and after

Pickett's and Pettigrew's famous assault on Meade's Second Corps. Continued below...

Interspersed

with humor and down-to-earth observations concerning battlefield conditions, the author conscientiously describes all aspects

of the battle, from massing of the assault columns and pre-assault artillery barrage to the last shots and the flight of the

surviving rebels back to the safety of their lines… Having visited Gettysburg several years ago, this superb volume makes me

want to go again.

Recommended

Reading:

Pickett's Charge--The Last Attack at Gettysburg (Hardcover). Description: Pickett's Charge

is probably the best-known military engagement of the Civil War, widely regarded as the defining moment of the battle of Gettysburg and celebrated as the high-water mark of the Confederacy.

But as Earl Hess notes, the epic stature of Pickett's Charge has grown at the expense of reality, and the facts of the attack

have been obscured or distorted by the legend that surrounds them. With this book, Hess sweeps away the accumulated myths

about Pickett's Charge to provide the definitive history of the engagement. Continued below...

Drawing on

exhaustive research, especially in unpublished personal accounts, he creates a moving narrative of the attack from both Union and Confederate

perspectives, analyzing its planning, execution, aftermath, and legacy. He also examines the history of the units involved,

their state of readiness, how they maneuvered under fire, and what the men who marched in the ranks thought about their participation

in the assault. Ultimately, Hess explains, such an approach reveals Pickett's Charge both as a case study in how soldiers

deal with combat and as a dramatic example of heroism, failure, and fate on the battlefield.

Recommended

Reading: General Lee's

Army: From Victory to Collapse. Review: You cannot say that University of North Carolina

professor Glatthaar (Partners in Command) did not do his homework in this massive examination of the Civil War–era lives

of the men in Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Glatthaar spent nearly 20 years examining and ordering primary source

material to ferret out why Lee's men fought, how they lived during the war, how they came close to winning, and why they lost.

Glatthaar marshals convincing evidence to challenge the often-expressed notion that the war in the South was a rich man's

war and a poor man's fight and that support for slavery was concentrated among the Southern upper class. Continued below...

Lee's army

included the rich, poor and middle-class, according to the author, who contends that there was broad support for the war in

all economic strata of Confederate society. He also challenges the myth that because Union forces outnumbered and materially

outmatched the Confederates, the rebel cause was lost, and articulates Lee and his army's acumen and achievements in the face

of this overwhelming opposition. This well-written work provides much food for thought for all Civil War buffs.

Recommended

Reading:

Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. Description: America's Civil War raged for more than four years, but it is the three days of fighting in the Pennsylvania countryside in July 1863 that continues to fascinate, appall, and inspire new

generations with its unparalleled saga of sacrifice and courage. From Chancellorsville, where General Robert E. Lee launched

his high-risk campaign into the North, to the Confederates' last daring and ultimately-doomed act, forever known as Pickett's

Charge, the battle of Gettysburg gave the Union army a victory that turned back the boldest and perhaps greatest chance for

a Southern nation. Continued below...

Now, acclaimed

historian Noah Andre Trudeau brings the most up-to-date research available to a brilliant, sweeping, and comprehensive history

of the battle of Gettysburg that sheds fresh light on virtually every aspect of it. Deftly balancing his own

narrative style with revealing firsthand accounts, Trudeau brings this engrossing human tale to life as never before.

Recommended

Reading: Gettysburg Heroes: Perfect Soldiers, Hallowed Ground (Hardcover). Description: The Civil War generation saw its world in ways startlingly different from our own.

In these essays, Glenn W. LaFantasie examines the lives and experiences of several key personalities who gained fame during

and after the war. The battle of Gettysburg is the thread

that ties these Civil War lives together. Gettysburg was a

personal turning point, though each person was affected differently. Continued below…

Largely biographical

in its approach, the book captures the human drama of the war and shows how this group of individuals--including Abraham Lincoln,

James Longstreet, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, William C. Oates, and others--endured or succumbed to the war and, willingly

or unwillingly, influenced its outcome. Concurrently, it shows how the war shaped the lives of these individuals, putting

them through ordeals they never dreamed they would face or survive.

Recommended Reading: Lost Triumph:

Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg--And Why It Failed. Description: A fascinating narrative-and

a bold new thesis in the study of the Civil War-that suggests Robert E. Lee had a heretofore undiscovered strategy at Gettysburg

that, if successful, could have crushed the Union forces and changed the outcome of the war. The Battle of Gettysburg is the

pivotal moment when the Union forces repelled perhaps America's greatest

commander-the brilliant Robert E. Lee, who had already thrashed a long line of Federal opponents-just as he was poised at

the back door of Washington, D.C.

It is the moment in which the fortunes of Lee, Lincoln, the Confederacy, and the Union hung precariously in the balance. Conventional wisdom has held to date, almost without exception,

that on the third day of the battle, Lee made one profoundly wrong decision. But how do we reconcile Lee the high-risk warrior

with Lee the general who launched "Pickett's Charge," employing only a fifth of his total forces, across an open field, up

a hill, against the heart of the Union defenses? Most history books have reported that Lee just had one very bad day. But

there is much more to the story, which Tom Carhart addresses for the first time. Continued below...

With meticulous

detail and startling clarity, Carhart revisits the historic battles Lee taught at West Point and believed were the essential

lessons in the art of war-the victories of Napoleon at Austerlitz, Frederick the Great at Leuthen, and Hannibal at Cannae-and

reveals what they can tell us about Lee's real strategy. What Carhart finds will thrill all students of history: Lee's plan

for an electrifying rear assault by Jeb Stuart that, combined with the frontal assault, could have broken the Union forces

in half. Only in the final hours of the battle was the attack reversed through the daring of an unproven young general-George

Armstrong Custer. About the Author: Tom Carhart has been a lawyer and a historian for the Department of the Army in Washington, D.C. He is

a graduate of West Point, a decorated Vietnam veteran, and has earned a

Ph.D. in American and military history from Princeton University. He is the author of four books of military history and teaches at Mary Washington College

near his home in the Washington, D.C.

area.

Recommended Reading: The History

Buff's Guide to Gettysburg (Key People, Places, and Events)

(Key People, Places, and Events). Description: While most history books are dry monologues of people, places, events and dates, The History Buff's Guide is ingeniously

written and full of not only first-person accounts but crafty prose. For example, in introducing the major commanders, the

authors basically call Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell a chicken literally. 'Bald, bug-eyed, beak-nosed Dick Stoddard

Ewell had all the aesthetic charm of a flightless foul.' Continued below...

To balance things back out a few pages later, they say federal Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade looked like

a 'brooding gargoyle with an intense cold stare, an image in perfect step with his nature.' Although it's called a guide to Gettysburg, in my opinion, it's an authoritative guide to

the Civil War. Any history buff or Civil War enthusiast or even that casual reader should pick it up.

|