|

American Civil War on the Outer Banks

Civil War Batters the Outer Banks

Introduction

The barrier islands of the North Carolina coast and the adjacent Pamlico

and Albemarle sounds were the gateway to the rest of the state during the American Civil War (1861-1865). Whoever could control

these barrier islands and sounds could control North Carolina. Although not as famous as other great Civil War battles, the

actions on the Outer Banks were pivotal for control of North Carolina.

The Outer Banks is a 200-mile (320-km) long string of narrow barrier islands off the coast of North Carolina,

beginning in southeastern corner of Virginia Beach on the east coast of the United States. They cover approximately half the

northern North Carolina coastline, separating the Currituck Sound, Albemarle Sound and Pamlico Sound from the Atlantic Ocean.

The area was the setting for important

engagements during the Civil War. Union victories at Hatteras Inlet and Roanoke Island early in the war placed the Outer Banks under Federal control and

extended their blockade of the Southern coast.

| Civil War on the Outer Banks, North Carolina |

|

| Battle of Roanoke Island |

| North Carolina Outer Banks and Civil War |

|

| Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries |

Summary

The Federal campaign began on August 27, 1861, with an amphibious

assault by Commodore Silas Stringham and General Benjamin Butler on two small and lightly defended forts at Cape Hatteras.

The Confederate government had placed a higher priority on the conflicts in Virginia, and thus had made little effort to outfit

and maintain these forts. The poorly-trained and poorly-equipped Confederate militia and recruits manning them were also plagued

by thirst and mosquitoes. The Federals took both forts in less than 48 hours, and not one Union soldier was killed. The entire

Pamlico Sound north to Roanoke Island was now open to Union activity, and for the Confederates the great highway linking coastal

shipping to the rivers of interior North Carolina was beginning to close.

A few months later, the Union assembled another fleet, this

time for an attack on Roanoke Island. Since the fall of the Hatteras forts, the Richmond government had done little to strengthen

the defense of Roanoke Island. There were three small earthen forts on the island, with a fourth position west of the island

across Croatan Sound (north of the current Manns Harbor Bridge). Because the Confederate general staff was expecting a Union

attack from the north, most of their artillery pieces were pointed in that direction and could not be turned to face an attack

from the south- Pamlico Sound. Due to the Confederate government's commitment to the defense of Richmond, only 1400 soldiers

were made available to hold the strategically important island.

After struggling south from Annapolis, Maryland, through a series of winter

storms, Union General Ambrose Burnside led a fleet of 67 ships and 13,000 men through Hatteras Inlet and dropped anchor off

the western shore of Roanoke Island on February 5, 1862. He landed 4000 soldiers at Ashby Harbor and after slogging through

the swamps assaulted the Confederates' makeshift position near today's intersection of U.S. 64 and N.C. 345. On Croatan Sound,

the South's five-vessel "Mosquito Fleet" harried the Union ships as best it could, but it was badly battered and quickly driven

north out of range.

The island's inexperienced defenders fought tenaciously behind their earthen

fortifications but were eventually outflanked and overwhelmed by Burnside's veterans. Few on either side were killed, and

the Union forces eventually captured the entire Southern defense contingent.

The "Mosquito Fleet" temporarily escaped to the north, but was destroyed a

few days later in a battle near Elizabeth City. The Union now controlled North Carolina's sounds and access to the state's interior shipping routes. It was a devastating

loss. The Federal campaigns on the Outer Banks helped accomplish President Lincoln's goal of a blockade of the Confederacy's

coastline, and helped foster cooperation and coordination between the Union's Army and Navy. Today, only one of the Confederate

defensive sites is accessible to visitors. Remnants of the ramparts near the U.S. 64-N.C. 345 intersection can be seen and

parking is available about 100 yards south of the intersection. The three

island forts, either worn down over the years or washed away into Croatan Sound, are commemorated by historic plaques and

street names throughout Roanoke Island.

| Outer Banks Civil War Battles |

|

| Civil War and the North Carolina Outer Banks. Courtesy Microsoft TerraServer. |

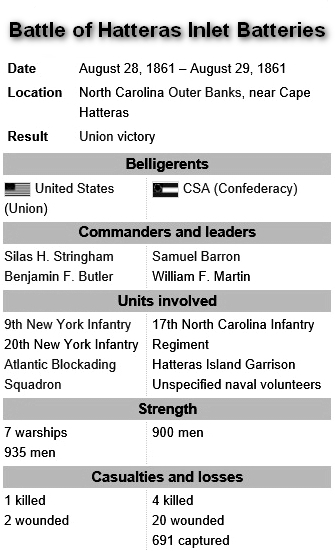

The Battle of Hatteras Inlet

In the 1860s Hatteras Inlet, between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, was the

most traveled and most vulnerable inlet on the Outer Banks. After North Carolina joined the Confederacy in 1861, soldiers

and slaves constructed Forts Clark and Hatteras, at the southern end of Hatteras Island in an effort to control access into

Pamlico Sound. The taking of Hatteras Inlet was an early priority for Union forces. On August 28, 1861, seven Federal ships

opened fire on Fort Clark. The great Union ships with their long guns remained far out to sea, well beyond the range of the

Confederates’ feeble artillery. By midday the poorly equipped Confederate troops at Fort Clark abandoned their stations

and fled to Fort Hatteras. A small contingent of Union soldiers landed and took Fort Clark. At dawn Union ships began bombardment

of Fort Hatteras. After hours of intense shelling, the Confederate commander surrendered the fort and its 700 men.

The taking of Hatteras Inlet was a morale boost for the Union and marked its

first victory in the war. This victory was so important that news was dispatched to the White House, where President Abraham

Lincoln, roused from bed in the middle of the night to receive the news, danced a jig in his nightshirt.

With the breakthrough at Hatteras Inlet, nearly all of the Confederate-held

East Coast between Wilmington, N.C., and Norfolk, Va., would begin to crumble. Pamlico Sound and its major cities of New Bern

and Washington, N.C., were the first step, but the Union had its sights on bigger prey.

The Chicamacomico Races

Roanoke Island remained a Confederate outpost and was the only thing standing

in the way of Union control of the Albemarle Sound, which along with Pamlico Sound, would mean total Union dominance of eastern

North Carolina. Confederate troops began massing on the island, and if their numbers swelled sufficiently, they could cross

the sound to recapture Hatteras Island and regain Pamlico Sound.

In October 1861, Union forces established an outpost 40 miles north of Hatteras

Inlet at Chicamacomico, today known as Rodanthe. When the Confederates discovered the Union presence in the village, they

launched an attack on the troops there. When the Federal commander saw Confederate ships crossing Pamlico Sound, he ordered

his men to flee south to Fort Hatteras. It was not easy going for the

Union soldiers as they fled from the Confederates. They struggled over the burning sand, shedding their clothes and shoes,

running for forty miles in bare feet. Wearied by exhaustion and dehydration, the Union soldiers camped at the Cape Hatteras

Lighthouse. Confederate troops camped further north near the village of Kinnakeet, now known as Avon.

Abandoning their planned attack, the Confederates began the march back to

Chicamacomico the next day. Additional Federal troops traveling north from Fort Hatteras passed the lighthouse and caught

up with the Confederates. Now it was the Confederates’ turn to run, all the way back to Chicamacomico. Both sides exchanged fire on land and sea, but recorded few casualties. The Confederates

returned to Roanoke Island, the Union to Fort Hatteras. This comic “battle” was derisively dubbed “the Chicamacomico

Races.” No changes in the balance of power occurred, but the Union continued planning for the eventual battle for Roanoke

Island and North Carolina’s northern waterways.

| Civil War Batters Outer Banks of North Carolina |

|

| Civil War Outer Banks History and Battles Map |

| North Carolina Outer Banks |

|

| (Civil War on the North Carolina Outer Banks) |

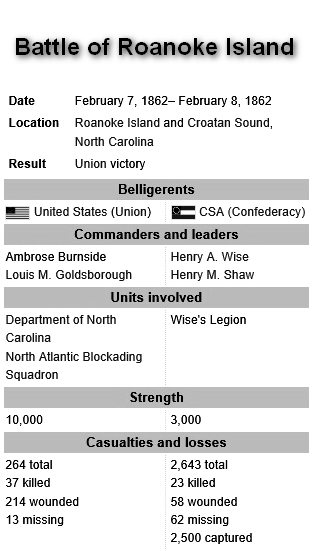

Battle of Roanoke Island

Union forces again set sights on Roanoke Island, the linchpin in North Carolina’s

coast. It was vital for Confederates to hold the island. If the Confederates lost Roanoke Island, it would only be a matter

of time before Albemarle Sound, its port cities, and back-door access to Norfolk would also be lost to the Union. Losing Roanoke

Island would mean losing all of eastern North Carolina. The Confederate commander on Roanoke Island had no military training,

but he recognized his vulnerable situation, pleading for reinforcements, but never receiving them. Only one road ran north

to south along the length of the island. Confederate troops built fortified earthworks on the road at the center of the island

to defend against a land-based assault. Confederates also constructed forts on the northwest coast of the island, enabling

cover of a water-based assault from the west. Union ships with their longer guns, came from the south, but remained easily

out of range of all but the southernmost fort, which they quickly disabled.

Late in the afternoon of February 7, 1862, Union troops landed with the aim

of assaulting the earthworks and road at the center of the island. The soldiers quickly captured the landing site and spent

a wet night before the battle. At dawn the Union troops successfully pushed through thick marshes to fire on the flanks of

the earthworks while others attacked from the front. The Confederate troops were overwhelmed, fleeing to the north end of

the island, where they ultimately surrendered Roanoke Island to the Union.

The fall of Roanoke Island opened eastern North Carolina to Union control.

By the summer of 1862, the port cities of Plymouth, Elizabeth City, New Bern, Washington, Edenton, Hertford, N.C., and Norfolk,

Va., had all fallen to Union forces. The vital rail line carrying supplies from Wilmington—North Carolina’s only

remaining Confederate port—was also vulnerable. With the huge success at Roanoke Island, the Union stranglehold on the

South was ever tightening.

*During World War II, because of the numerous allied ships sunk by German U-boats, the waters off Cape Hatteras

were known as Torpedo Alley.

(Sources and related reading below.)

Recommended Reading: The

Civil War on the Outer Banks: A History of the Late Rebellion Along the Coast of North Carolina from Carteret to Currituck

With Comments on Prewar Conditions and an Account of (251 pages). Description: The ports at Beaufort, Wilmington, New Bern and Ocracoke, part of the Outer Banks (a chain

of barrier islands that sweeps down the North Carolina coast from the Virginia Capes to Oregon Inlet), were strategically

vital for the import of war materiel and the export of cash producing crops. From official records, contemporary newspaper

accounts, personal journals of the soldiers, and many unpublished manuscripts and memoirs, this

is a full accounting of the Civil War along the North Carolina

coast.

Advance to:

Recommended Reading: The

Civil War in Coastal North Carolina (175 pages) (North Carolina Division of Archives and History). Description: From the drama of blockade-running to graphic descriptions of battles

on the state's islands and sounds, this book portrays the explosive events that took place in North Carolina's

coastal region during the Civil War. Topics discussed include the strategic importance of coastal North Carolina, Federal occupation of coastal areas, blockade-running, and the impact of

war on civilians along the Tar Heel coast.

Recommended Reading: Ironclads and Columbiads: The Coast

(The Civil War in North Carolina) (456 pages). Description: Ironclads and Columbiads covers some of the most

important battles and campaigns in the state. In January 1862, Union forces began in earnest to occupy crucial points on the

North Carolina coast. Within six months, Union army and

naval forces effectively controlled coastal North Carolina from the Virginia

line south to present-day Morehead City.

Union setbacks in Virginia, however, led to the withdrawal of many federal soldiers from North Carolina, leaving only enough

Union troops to hold a few coastal strongholds—the vital ports and railroad junctions. The South during the Civil War,

moreover, hotly contested the North’s ability to maintain its grip on these key coastal strongholds.

Recommended Reading: Storm

over Carolina: The Confederate Navy's Struggle for Eastern North Carolina. Description: The struggle for control of the eastern

waters of North Carolina during the War Between the States

was a bitter, painful, and sometimes humiliating one for the Confederate navy. No better example exists of the classic adage,

"Too little, too late." Burdened by the lack of adequate warships, construction facilities, and even ammunition, the

South's naval arm fought bravely and even recklessly to stem the tide of the Federal invasion of North

Carolina from the raging Atlantic. Storm

Over Carolina is the account of the Southern navy's struggle in North

Carolina waters and it is a saga of crushing defeats interspersed with moments of brilliant and even

spectacular victories. It is also the story of dogged Southern determination and incredible perseverance in the face

of overwhelming odds. Continued below...

For most of

the Civil War, the navigable portions of the Roanoke, Tar, Neuse, Chowan, and Pasquotank rivers were

occupied by Federal forces. The Albemarle and Pamlico sounds, as well as most of the coastal towns and counties, were also

under Union control. With the building of the river ironclads, the Confederate navy at last could strike a telling blow against

the invaders, but they were slowly overtaken by events elsewhere. With the war grinding to a close, the last Confederate vessel

in North Carolina waters was destroyed. William T. Sherman

was approaching from the south, Wilmington was lost, and the

Confederacy reeled as if from a mortal blow. For the Confederate navy, and even more so for the besieged citizens of eastern

North Carolina, these were stormy days indeed. Storm Over Carolina describes their story, their struggle, their history.

Recommended

Reading: American Civil

War Fortifications (1): Coastal brick and stone forts (Fortress). Description: The 50 years before the American Civil War saw a boom in the construction of coastal forts

in the United States of America. These

stone and brick forts stretched from New England to the Florida Keys, and as far as the Mississippi River.

At the start of the war some were located in the secessionist states, and many fell into Confederate hands. Although a handful

of key sites remained in Union hands throughout the war, the remainder had to be won back through bombardment or assault.

This book examines the design, construction and operational history of those fortifications, such as Fort

Sumter, Fort Morgan

and Fort Pulaski,

which played a crucial part in the course of the Civil War.

Sources: National Park Service; Fort Raleigh National Historic Site; Official

Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; New Bern Historical Society; North Carolina Civil War Tourism Council, Inc; North

Carolina Museum of History.

This page discuses the following: North Carolina Coast Civil War History, Map of North Carolina Coast during

the Civil War, Outer Banks Civil War History, Confederate Navy North Carolina Coast, and North Carolina Naval Battle

and Battles.

|