|

Blockade of the Carolina Coast [August-December 1861]

Introduction

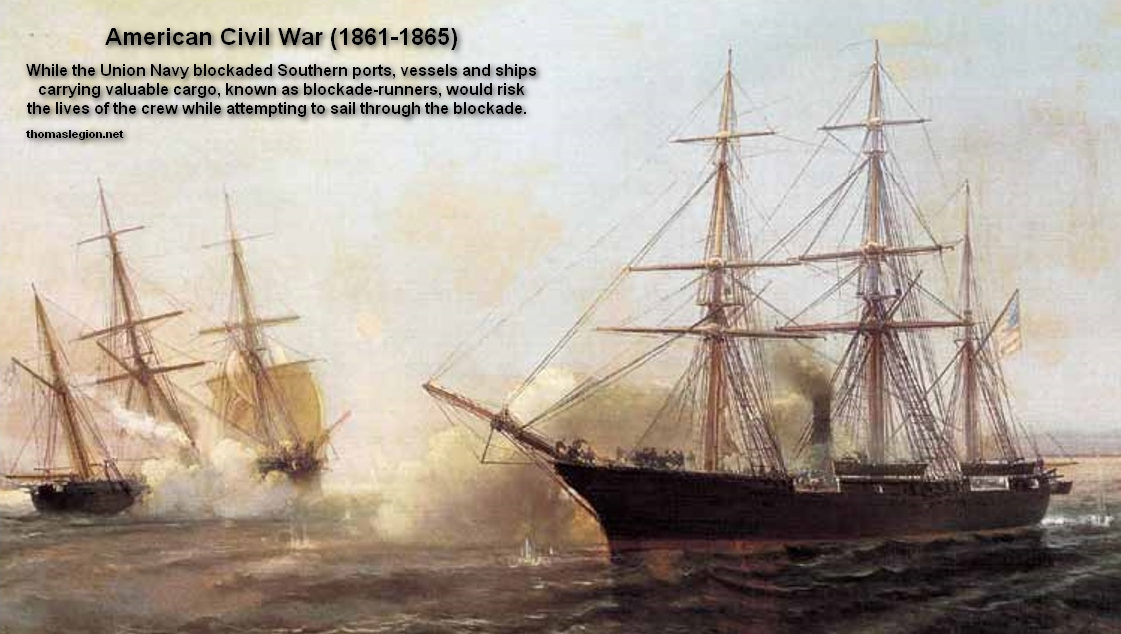

The Union blockade during the American Civil War (1861-1865), which included

the Blockade of the Carolina Coast, was a naval strategy by Washington to prevent the Confederacy from trading. The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required

the monitoring of more than 3,000 miles of Atlantic and Gulf coastline, including 12 major ports, notably New Orleans and

Mobile.

Many attempts to run the blockade were successful, however. It was

during the Federal blockade that England delivered sixty percent of all the Enfield rifles used by the Confederate

Army. The transport of the much needed supplies to the Southern states was an invaluable contribution

by the blockade-runners to the Confederate war effort. The blockade-runners

were operated largely by British citizens, making use of neutral ports such as Havana, Nassau and Bermuda. The 500 ships commissioned

by the Union would capture or destroy 1,500 blockade-runners during the course of the war.

| Blockade of the Carolina Coast |

|

| Blockade-runners of the Civil War |

Summary

The Union Blockade of the North Carolina Coast was designed to prevent the passage of goods, supplies, and arms to and from

the Confederacy. (See also Civil War Blockade Organization.) It refers to U.S. naval actions between 1861 and 1865 in which the Union Navy maintained a massive blockading

effort on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts

of the Confederate States. The

Blockade of the Carolina Coast, a strategic objective early in the war, would include the Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries and was part of General Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan.

Background

North Carolina had

scarcely armed and equipped its men before sending nearly all of them into Virginia by mid-1861. In the summer of 1861,

Governor Henry Toole Clark said that North Carolina's State Troops, especially her best-armed and best-trained regiments, were nearly

all in Virginia, and all her coast defenses were, like Hatteras, poorly armed and insufficiently manned. Clark, in a letter to the Confederate Secretary of War, thus

states the affairs in the State:

"We feel defenseless here without arms... We

see just over our lines in Virginia, near Suffolk, two or three North Carolina regiments, well armed and well drilled, who

are not allowed to come to the defense of their homes... We are threatened with an expedition of 15,000 men. That is the amount

of our seaboard army, extending along four-hundred miles of territory, and at no point can we spare a man, and without arms,

we can not increase it... We have now collected in camps about three regiments without arms, and our only reliance is the

slow collection of shotguns and hunting rifles, and it is difficult to buy, for the people are now hugging their arms for

their own defense."

| Civil War Union Naval Blockade Map |

|

| Union Blockade of the Southern Coast |

|

| Union gunboat |

North Carolina Coast

The North Carolina Sounds occupy most of the coast from Cape Lookout (North

Carolina) to the Virginia border. With their eastern borders marked by the Outer Banks, they were almost ideally located for

raiding Northern maritime commerce. Cape Hatteras, located on the Outer Banks, is the easternmost point of the Confederacy

and within sight of the Gulf Stream. Ships in the Caribbean trade would reduce the time of their homeward journeys to New

York, Philadelphia, or Boston by riding the stream to the north.

Raiders, either privateers or state-owned vessels, could lie inside, protected

from both the weather and from Yankee blockaders, until an undefended victim appeared. Watchers stationed at the Hatteras

lighthouse would then signal a raider, which would dash out and make a capture, often being able to return the same day. To

protect the raiders from Federal reprisal, the state of North Carolina, immediately after seceding from the Union, established

forts at the inlets, the waterways that allowed entrance to and egress from the sounds.

In 1861, only four inlets were deep enough for ocean-going vessels to pass:

Beaufort, Ocracoke, Hatteras, and Oregon Inlets. Hatteras Inlet was the most important of these, so it was given two forts,

named Fort Hatteras and Fort Clark Fort Hatteras was sited adjacent to the inlet, on the sound side of Hatteras Island. Fort

Clark was about half a mile to the southeast, closer to the Atlantic Ocean. The forts were not the most formidable of

the Confederacy, however. Fort Hatteras had only ten guns mounted by the end of August, with another five guns in the

fort but not mounted. Fort Clark had only five. Furthermore, most of the guns were rather light 32-pounders or smaller, of

limited range and inadequate for coastal defense.

| North Carolina Civil War Battles |

|

| Blockade of the Carolina Coast |

The depredations on Northern commerce emanating from Hatteras Inlet could

not pass unnoticed. Insurance underwriters pressured Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles for remedy. Welles needed no

prodding. He already had on his desk a report from the Blockade Strategy Board suggesting a way to perfect the blockade of

the North Carolina coast. The board recommended that the coast be rendered useless to the South by sinking old, useless, ballast-laden

ships in the inlets to block them up.

Soon after he received the board's report, Secretary Welles began to implement

its recommendation. He ordered Commander H. S. Stellwagen to go to the Chesapeake Bay to buy some suitable old hulks. At the

same time, he was told to report his activities to Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham, commandant of the Atlantic Blockading

Squadron. As such, he was the naval officer in charge of the blockade of the North Carolina coast. This was the first involvement

of Stringham with what was to become the attack at Hatteras Inlet. In time, he would become the most important person in the

expedition.

Stringham opposed the plan to block the inlets from the beginning. He believed

that the tidal currents would either sweep the impediments away or would rapidly scour new channels. As he saw it, the Rebels

could not be denied access to the sounds unless the inlets were actually held by the Union. In other words, in order to establish

an effective blockade in this part of North Carolina, the forts that the state had set up would have to be captured. Since

the Navy could not do it alone, the cooperation of the Army would be needed.

As it happened, the Army was willing to cooperate. This was partially due

to the political general Benjamin F. Butler, who was a political force that had to be dealt with, but was already emerging

as a military incompetent. Butler was ordered to assemble a force of some 800 men for the expedition. He soon had 880: 500

from the German-speaking 20th New York Volunteers, 220 from the 9th New York Volunteers, 100 from the Union Coast Guard (an

Army unit, actually the 99th New York Volunteers; the U.S. Coast Guard as we know it did not exist in 1861), and 20 army regulars

from the 2nd U.S. Artillery. The men were put aboard two of the vessels that Commander Stellwagen had purchased, Adelaide

and George Peabody. When objection was made that the two ships would not be able to survive a Hatteras storm, Stellwagen pointed

out that the expedition could proceed only in fair weather anyway, as a storm would prevent landings.

While Butler was gathering his forces, Flag Officer Stringham was also making

preparations. Somehow he learned that the War Department orders to Butler's superior, Major General John E. Wool, had contained

the statement, "The expedition originated in the Navy Department, and is under its control." Reasoning that he would be blamed

if anything went wrong, he decided to follow his own plans. He selected seven warships for the expedition: USS Minnesota,

Cumberland, Susquehanna, Wabash, Pawnee, Monticello, and Harriet Lane. All but the last were ships of the U.S. Navy; Harriet

Lane was a cutter, part of the US Revenue Service. He also included in his force the tug Fanny, needed to tow some of the

surf boats that would be used for the landing.

On August 26, 1861, the flotilla, less Susquehanna and Cumberland, departed

Hampton Roads and moved down the coast to the vicinity of Cape Hatteras. On the way, they were joined by Cumberland. They

swung around the Cape on August 27 and anchored near the inlet, in full view of the defenders there. Colonel William F. Martin

of the 7th North Carolina Infantry, commanding at Forts Hatteras and Clark, knew that his 580 or so men would need help, so

he called for reinforcements from Forts Ocracoke and Oregon. Unfortunately for him and his garrison, communication among the

forts was slow, and the first reinforcements did not arrive until late the next day, when it was too late.

| Blockade of the Carolina Coast |

|

| Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries |

| Blockade of Carolina Coast |

|

| Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries |

1Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory

Commission Report.

Battle of Hatteras Inlet

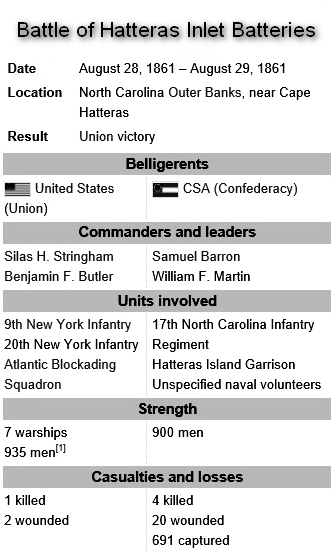

The Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries, sometimes known as the Battle of

Forts Hatteras and Clark, was a small but significant engagement in the early days of the American Civil War. Two Confederate

forts on the North Carolina Outer Banks were subjected to an amphibious assault by Union forces that began on August 28, 1861.

The ill-equipped and undermanned forts were forced to endure bombardment by seven Union warships, to which they were unable

to reply. Although casualties were light, the defenders chose not to continue the one-sided contest, and on the second day

they surrendered. As immediate results of the battle, Confederate interference with Northern maritime commerce was considerably

reduced, while the Union blockade of Southern ports was extended. More importantly, the Federal government gained entry into

the North Carolina Sounds. Several North Carolina cities (New Bern, Washington, Elizabeth City, and Edenton among them) were

directly threatened. In addition, the sounds were a back door to the Confederate-held parts of Tidewater Virginia, particularly

Norfolk.

The battle is significant for several reasons: It was the first notable

Union victory of the war; following the embarrassment of First Bull Run (or First Manassas), July 21, 1861, it encouraged

supporters of the Union in the gloomy early days. It represented the first application of the naval blockading strategy. It

was the first amphibious operation, as well as the first combined operation, involving units of both the United States Army

and Navy. Finally, a new tactic was exploited by the bombarding fleet; by keeping in motion, they did much to eliminate the

traditional advantage of shore-based guns over those carried on ships.

Aftermath

Butler and Stringham left immediately after the battle, the former to Washington

and the latter accompanying the prisoners to New York. Critics argued that each was trying to gather credit for the victory

to himself. The pair contended, however, that they were trying to persuade the administration to abandon the original plan

to block up Hatteras Inlet. In Federal hands it was no longer useful to the Confederacy, and in fact now allowed Union forces

to pursue raiders into the sounds. Although they and their supporters continued to press the case for several weeks, it seems

to have been unnecessary. The War and Navy Departments had already decided to retain possession of the inlet, which would

be used as the entry point of an amphibious expedition against the North Carolina mainland early the next year. This campaign,

known as Burnside's North Carolina Expedition for its senior Army commander Ambrose E. Burnside, completely removed the sounds

as sources of commerce-raiding activity.

Continued Federal possession of Hatteras Inlet was considerably aided by

the Confederate authorities, who early decided that the Ocracoke and Oregon batteries were indefensible, so they were abandoned.

Stringham's tactic of keeping his ships in motion while bombarding forts

was used later by Flag Officer Samuel Francis Du Pont at Port Royal, South Carolina. The effectiveness of the practice led

to a reconsideration of the value of fixed forts against naval gunnery.

Blockade of the Carolina Coast

[August-December 1861]

Recommended Reading:

Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running

During the Civil War (Studies in Maritime

History Series). From Library Journal: From the profusion of books about Confederate blockade running, this one will stand

out for a long time as the most complete and exhaustively researched. …Wise sets out to provide a detailed study, giving

particular attention to the blockade runners' effects on the Confederate war effort. Continued below...

It was, he finds, tapping hitherto unused sources, absolutely essential, affording the South a virtual lifeline

of military necessities until the war's last days. This book covers it all: from cargoes to ship outfitting, from individuals

and companies to financing at both ends. An indispensable addition to Civil War literature.

Recommended

Reading: Naval Campaigns of the Civil War.

Description: This analysis of naval engagements during the War Between the States presents the action from the efforts at

Fort Sumter during the secession of South Carolina in 1860, through the battles in the Gulf of Mexico, on the Mississippi

River, and along the eastern seaboard, to the final attack at Fort Fisher on the coast of North Carolina in January 1865.

This work provides an understanding of the maritime problems facing both sides at the beginning of the war, their efforts

to overcome these problems, and their attempts, both triumphant and tragic, to control the waterways of the South. The Union

blockade, Confederate privateers and commerce raiders are discussed, as is the famous battle between the Monitor and the Merrimack. Continued below…

An overview

of the events in the early months preceding the outbreak of the war is presented. The chronological arrangement of the campaigns

allows for ready reference regarding a single event or an entire series of campaigns. Maps and an index are also included.

About the Author: Paul Calore, a graduate of Johnson and Wales University,

was the Operations Branch Chief with the Defense Logistics Agency of the Department of Defense before retiring. He is a supporting

member of the U.S. Civil War Center and the Civil War Preservation Trust and has also written Land Campaigns of the Civil

War (2000). He lives in Seekonk, Massachusetts.

Recommended

Reading: Confederate Blockade Runner 1861-65

(New Vanguard). Description: The lifeblood of the Confederacy, the blockade runners of the Civil War usually began life as

regular fast steam-powered merchant ships. They were adapted for the high-speed dashes through the Union blockade which closed

off all the major Southern ports, and for much of the war they brought much-needed food, clothing and weaponry to the Confederacy.

This book traces their operational history, including the development of purpose-built blockade running ships, and examines

their engines, crews and tactics. It describes their wartime exploits, demonstrating their operational and mechanical performance,

whilst examining what life was like on these vessels through accounts of conditions on board when they sailed into action.

Recommended

Reading:

Civil War Navies, 1855-1883 (The U.S. Navy Warship Series) (Hardcover). Description: Civil War Warships, 1855-1883

is the second in the five-volume US Navy Warships encyclopedia set. This valuable reference lists the ships of the U.S. Navy

and Confederate Navy during the Civil War and the years immediately following - a significant period in the evolution of warships,

the use of steam propulsion, and the development of ordnance. Civil War Warships provides a wealth and variety of material

not found in other books on the subject and will save the reader the effort needed to track down information in multiple sources.

Continued below…

Each

ship's size and time and place of construction are listed along with particulars of naval service. The author provides historical

details that include actions fought, damage sustained, prizes taken, ships sunk, and dates in and out of commission as well

as information about when the ship left the Navy, names used in other services, and its ultimate fate. 140 photographs, including

one of the Confederate cruiser Alabama recently uncovered by the author further contribute to this

indispensable volume. This definitive record of Civil War ships updates the author's previous work and will find a lasting

place among naval reference works.

Recommended Reading:

Rebels and Yankees: Naval Battles of the Civil War (Hardcover). Description:

Naval Battles of the Civil War, written by acclaimed Civil War historian Chester G. Hearn, focuses on the maritime battles

fought between the Confederate Rebels and the Union forces in waters off the eastern seaboard and the great rivers of the

United States during the Civil War. Continued

below...

Since very few books have been written on this subject, this volume provides a fascinating and vital portrayal

of the one of the most important conflicts in United States history. Naval Battles

of the Civil War is lavishly illustrated with rare contemporary photographs, detailed artworks, and explanatory maps, and

the text is a wonderful blend of technical information, fast-flowing narrative, and informed commentary.

|